From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gaming and PSU

2.2. SNS and PSU

2.3. Shopping and PSU

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. COVID-19 Context

3.2. Moderating Role of COVID-19

4. Methodology

4.1. Participant

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

5. Analyses and Results

5.1. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

5.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Summary

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elhai, J.D.; Hall, B.J.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D. Types of smartphone usage and relations with problematic smartphone behaviors: The role of content consumption vs. social smartphone use. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J. Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wölfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Müller, A.; Wölfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.A.; McCarthy, S. Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Schivinski, B.; Pontes, H.M.; Montag, C. Problematic online behaviors among gamers: The links between problematic gaming, gambling, shopping, pornography use, and social networking. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H.; Kim, H.; Yum, J.-Y.; Hwang, Y. What type of content are smartphone users addicted to?: SNS vs. games. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, D.M. Why do some people become addicted to digital games more easily? A study of digital game addiction from a psychosocial health perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 33, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2019, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglass, S.L.; Binder, J.F.; Betts, L.R.; Underwood, J.D. Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network site use and FOMO. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ali, F.; Tauni, M.Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ahsan, T. Effects of hedonic shopping motivations and gender differences on compulsive online buyers. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2022, 30, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Vogel, M.; Sobek, C.; Meigen, C.; Körner, A.; Kiess, W. Smartphone use, wellbeing, and their association in children: Longitudinal evidence from the LIFE Child study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025; advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Longitudinal associations between problematic smartphone use and sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict. Behav. 2023, 139, 107600. [Google Scholar]

- Király, O.; Potenza, M.N.; Stein, D.J.; King, D.L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjoneska, B.; Billieux, J.; Brand, M.; et al. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 152180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Cost, K.T.; Charach, A.; Maguire, J.L.; Monga, S.; Crosbie, J.; Burton, C.; Anagnostou, E.; et al. Screen use and mental health symptoms in Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2023; OECD Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, S.S.; Yang, H. Resisting problematic smartphone use: Distracter resistance strengthens grit’s protective effect against problematic smartphone use. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 194, 111644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Grote, L.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Felnhofer, A. Risk factors for problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents: A review of existing literature. Neuropsychiatrie 2019, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Männikkö, N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J. Mobile gaming and problematic smartphone use: A comparative study between Belgium and Finland. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Seydavi, M.; Sheikhi, S.; Wright, P.J. Exploring differences in four types of online activities across individuals with and without problematic smartphone use. Psychiatr. Q. 2024, 95, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Borda-Mas, M. Problematic smartphone use and specific problematic Internet uses among university students and associated predictive factors: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 7111–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.J.; Yeo, K.J.; Handayani, L. Types of smartphone usage and problematic smartphone use among adolescents: A review of literature. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2023, 12, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.-J.; Kim, D.-J. Investigating psychological and motivational predictors of problematic smartphone use among Smartphone-based social networking service (SNS) users. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2023, 18, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, C.; Canale, N.; Melodia, F.; Spada, M.M.; Vieno, A. The overlap between problematic smartphone use and problematic social media use: A systematic review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzeiro, V.; Martins, C.; Gonçalves, C.; Santos, A.R.; Costa, R.M. Sexual function and problematic use of smartphones and social networking sites. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugtekin, U.; Tugtekin, E.B.; Kurt, A.A.; Demir, K. Associations between fear of missing out, problematic smartphone use, and social networking services fatigue among young adults. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120963760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sheffield, D. An investigation into problematic smartphone use: The role of narcissism, anxiety, and personality factors. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jeong, J.-E.; Rho, M.J. Predictors of habitual and addictive smartphone behavior in problematic smartphone use. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrhinen, J.; Lonka, K.; Sirola, A.; Ranta, M.; Wilska, T. Young adults’ online shopping addiction: The role of self-regulation and smartphone use. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1871–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Laskowski, N.M.; Wegmann, E.; Steins-Loeber, S.; Brand, M. Problematic online buying-shopping: Is it time to considering the concept of an online subtype of compulsive buying-shopping disorder or a specific internet-use disorder? Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N.R.; Zhai, Z.W.; Hoff, R.A.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Potenza, M.N. Problematic shopping and self-injurious behaviors in adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; McKay, D.; Yang, H.; Minaya, C.; Montag, C.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Health anxiety related to problematic smartphone use and gaming disorder severity during COVID-19: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Sujan, S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Mohona, R.A.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Kamruzzaman, S.; Toma, T.Y.; Sakib, N.; Pinky, K.N.; Islam, R.; et al. Problematic smartphone and social media use among Bangladeshi college and university students amid COVID-19: The role of psychological well-being and pandemic related factors. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 647386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.R.; Larson, J.; Richards, S.; Larson, S.; Nienstedt, C. The COVID-19 pandemic: Electronic media use and health among U.S. college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 72, 3261–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, I.; Al Mamun, F.; Sikder, M.T.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Zou, L.; Guo, T.; Mamun, M.A. Prevalence and associated factors of problematic smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Bangladeshi study. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2021, ume 14, 3797–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, N.; Habtamu, E.; Kassaw, C.; Madoro, D.; Molla, W.; Wudneh, A.; Abebe, L.; Duko, B.; Zou, D. Problematic smartphone and social media use among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: In the case of southern Ethiopia universities. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Chen, J.H.; Tong, K.K.; Yu, E.W.-Y.; Wu, A.M.S. Problematic smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Its association with pandemic-related and generalized beliefs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, B.; Ok, C. Impact of digital literacy and problematic smartphone use on life satisfaction: Comparing pre-and post-COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Hao, Z.; Huang, J.; Akram, H.R.; Saeed, M.F.; Ma, H. Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: The mediation models. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 121, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, B.K. Children’s screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: Boundaries and etiquette. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mu, W.; Xie, X.; Kwok, S.Y. Network analysis of internet gaming disorder, problematic social media use, problematic smartphone use, psychological distress, and meaning in life among adolescents. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231158036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Chen, R.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J. Associations of problematic smartphone use with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in university students before and after the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 2024, 152, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Um, N.R.; Kim, H.S. The Survey on Smartphone Overdependence; Ministry of Science and ICT, National Information Society Agency: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017.

- Park, J.H.; Park, M.; Horowitz-Kraus, T. Smartphone use patterns and problematic smartphone use among preschool children. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online gaming addiction in children and adolescents: A review of empirical research. J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienstedt, C.; Smith, N.; Braithwaite, H.; Gilbert, B.; Wright, R.R. Swiping away our wellbeing? Examining TikTok use among college students. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2023, 28, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Wang, H.-Z.; Gaskin, J.; Wang, L.-H. The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.R.; Brough, S.; Castro, J.; Osborne, M.; Johnson, L.; Johnson, S. State of the first semester freshman: Health and wellness through the COVID-19 pandemic, years 2018-2023. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2025, 30, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.R.; Evans, A.; Schaeffer, C.; Mullins, R.; Cast, L. Social networking site use: Implications for health and wellness. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2021, 26, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, C.R.; Nienstedt, C.; Wright, R.R.; Chambers, S. Social media use motives: An influential factor in user behavior and user health profiles. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2023, 28, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSU | (0.80) | |||||||||

| 2. Gaming | 0.22 * | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. SNS | 0.20 * | 0.38 * | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. Online Shopping | 0.13 * | 0.26 * | 0.51 * | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. Post-COVID-19 | −0.06 * | −0.25 * | −0.28 * | −0.18 * | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. Gender | 0.03 * | 0.12 * | −0.02 * | −0.07 * | −0.02 * | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. Age | −0.24 * | −0.33 * | −0.34 * | −0.15 * | 0.17 * | 0.02 * | 1.00 | |||

| 8. Income | 0.06 * | 0.07 * | 0.12 * | 0.11 * | 0.05 * | 0.02 * | −0.15 * | 1.00 | ||

| 9. Education Level | 0.04 * | 0.04 * | 0.24 * | 0.36 * | −0.10 * | 0.09 * | −0.09 * | 0.14 * | 1.00 | |

| 10. DL | 0.18 * | 0.26 * | 0.36 * | 0.33 * | −0.05 * | 0.06 * | −0.33 * | 0.17 * | 0.30 * | (0.81) |

| Mean | 1.95 | 3.63 | 4.12 | 4.08 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 41.12 | 3.12 | 14.00 | 2.77 |

| S.D. | 0.53 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 1.90 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 15.20 | 0.98 | 2.61 | 0.60 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | β | s.e. | b | β | s.e. | b | β | s.e. | b | β | s.e. | |

| Constant | 1.981 * | N/A | 0.014 | 1.837 * | N/A | 0.015 | 1.814 * | N/A | 0.015 | 1.899 * | N/A | 0.015 |

| Gender | 0.028 * | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.019 * | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.019 * | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.018 * | 0.017 | 0.003 |

| Age | −0.007 * | −0.207 | 0.0001 | −0.005 * | −0.154 | 0.0001 | −0.005 * | −0.156 | 0.0001 | −0.005 * | −0.150 | 0.0001 |

| Income | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Education Level | −0.002 * | −0.012 | 0.0007 | −0.005 * | −0.025 | 0.0007 | −0.004 * | −0.023 | 0.0007 | −0.006 * | −0.031 | 0.0007 |

| DL | 0.098 * | 0.112 | 0.003 | 0.059 * | 0.068 | 0.003 | 0.056 * | 0.064 | 0.003 | 0.056 * | 0.064 | 0.003 |

| Gaming | 0.030 * | 0.118 | 0.001 | 0.032 * | 0.123 | 0.001 | 0.032 * | 0.126 | 0.001 | |||

| SNS | 0.019 * | 0.074 | 0.001 | 0.021 * | 0.081 | 0.001 | 0.016 * | 0.064 | 0.001 | |||

| Online Shopping | 0.007 * | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.007 * | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.001 | |||

| Post-COVID-19 | 0.034 * | 0.031 | 0.003 | 0.013 * | 0.012 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Post-COVID-19 * Gaming | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.002 | |||||||||

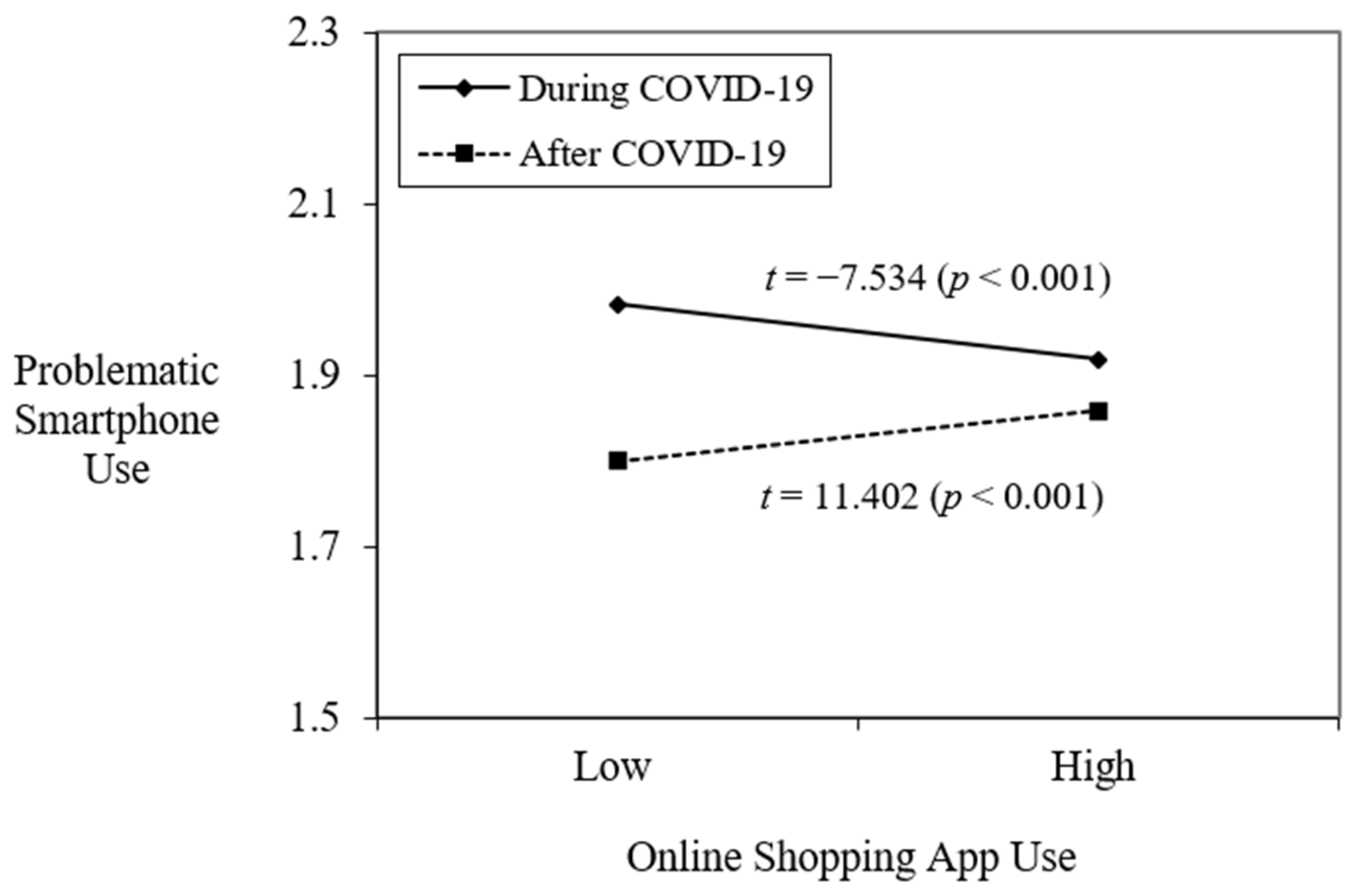

| Post-COVID-19 * SNS | 0.029 * | 0.049 | 0.002 | |||||||||

| Post-COVID-19 * Online Shopping | 0.032 * | 0.052 | 0.002 | |||||||||

| F-Value | 1160.48 * | 988.16 * | 887.40 * | 718.48 * | ||||||||

| R-Squared | 0.0714 | 0.0948 | 0.0957 | 0.1026 | ||||||||

| Δ R-Squared | 0.0714 | 0.0234 | 0.0009 | 0.0069 | ||||||||

| Adj. R-Squared | 0.0714 | 0.0948 | 0.0956 | 0.1024 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ok, C. From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19. COVID 2025, 5, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100163

Ok C. From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19. COVID. 2025; 5(10):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100163

Chicago/Turabian StyleOk, Chiho. 2025. "From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19" COVID 5, no. 10: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100163

APA StyleOk, C. (2025). From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19. COVID, 5(10), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100163