1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought dramatic changes in how firms and consumers operate, affecting the economy and the entire society [

1]. There has been a 75.6 percent decline in international passenger demand since the pandemic in 2020 [

2]. According to Davitt [

2], there has been a 70% decrease in bookings for future travel. This has led to increased financial difficulty for airlines and further delays in industry recovery. According to Tang [

3]), Malaysian passenger movements also decreased by 75.5 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, apart from the industry’s own analysis and strategy plan for recovery of the aviation industry, the other side of consumer behavior and confidence level to fly again is just as important to be analyzed.

It has been observed that a substantial volume of literature has been produced throughout the years 2020–2022 regarding the empirical evidence of the consequences of the recent pandemic. Among the areas investigated were changes in individual preventive behavior [

4], health risk perception [

5,

6], shifts from commuting to telecommuting [

7], and increased adoption of sustainable and innovative transportation modes [

8]. These modes complemented existing transportation networks and facilitated physical distancing measures. In the literature, travel intention studies have been explored based on behavioral intentions. However, the relationship between psychological constructs affecting individuals’ mindsets, confidence, and travel intention is limited [

9,

10].

These studies (have improved our understanding of travel intentions by examining trust, solidarity, and electronic word of mouth [

9,

10]. They mainly focused on media exposure and destination image influencing travel intentions. However, they have not investigated the internal psychological processes that affect individual confidence and travel intentions during times of uncertainty. However, how the cognitive appraisals and self-regulatory beliefs influence intentions in post-crisis contexts is yet to be explored. Therefore, the present study framework addresses this gap by integrating core psychological constructs, i.e., perceived risk, perceived severity, perceived barriers, perceived vaccination effectiveness, and self-efficacy to intention to travel. The present study approach draws attention from health behavior theories, i.e., the Health Belief Model and Protection Motivation theory, to highlight how cognitive appraisals and self-regulatory beliefs influence travel intentions among the medical students of Malaysia. Medical professionals have a heightened awareness of health risks. They have seen the pandemic’s dangerous situation very closely and faced unique stressors during the pandemic. Therefore, mental health, burnout, and emotional well-being may influence their travel intentions. A study of this group could offer new insights into evidence-based decision-making coping mechanisms. It provides valuable insight into consumer behavior for the decision-making of a particular group in the aviation and tourism industries during the post-pandemic period. A data-driven approach to air travel demands prediction, and insights from the study can contribute to industry recovery during an epidemic.

By 2025, fears about COVID-19 travel will have diminished, but studies such as these will remain highly relevant for research, policy, and practice. Results demonstrated that psychological constructs, such as perceived travel risk, severity, barriers, vaccination effectiveness, and self-efficacy, significantly influence travelers’ intentions. These constructs are not unique; they can define traveler behavior during future public health crises or disruptions.

From a research standpoint, this study extends the HB Model into the context of post-pandemic travel and validates intention formation through risk perceptions and coping conceptualizations. From a policy standpoint, it stresses the importance of creating health communication practices that build self-efficacy and confidence while addressing perceived risks. From a practical perspective, a psychological understanding of travelers can inform marketing, communication, and service strategies within the tourism and aviation sectors to facilitate recovery and build resilience against future crises.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The existing literature utilized several theories to analyze the intention and readiness of air travel during the recent pandemic. These include the protection motivation theory [

11]; The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

12]; the uncertainty avoidance theory [

13] and the health belief model [

14]. These different theories are used in analyzing air travel intention and to justify health behavior during the pandemic [

15].

The health belief model (HBF) explains and predicts individuals’ health-related behaviors. It takes into account various psychological traits that influence the decision-making process [

14]. This model asks individuals why they engage in health-promoting behaviors and how they make health decisions. The HBM seeks to understand how individuals make health decisions and suggests several factors influencing people’s health-related behaviors. Healthcare research and intervention areas like understanding health prevention behaviors [

16], utilizing health screenings, adhering to treatment plans [

17], conducting health education campaigns, and organic farming [

18] have adapted to the HBM framework. Numerous studies have adopted the HBF to investigate people’s intentions to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Although previous studies have examined various frameworks to figure out health-related behaviors during the pandemic, the current study incorporated the constructs of the social cognitive theory (SCT) [

19], specifically “self-efficacy,” into the HBM. Bandura’s model is frequently used to explain health behavior. The social cognitive theory combines cognitive and behavioral perspectives to explain human behavior. Hence, integrating the health belief model and SCT helps understand health risk perception and individuals’ beliefs and motivation to achieve a specific goal. Although several existing studies have extensively analyzed the factors of air travel intention, integrating the HBM and SCT helps link the influence of health risk perception and individuals’ beliefs and motivation in achieving a specific goal.

2.2. Perceived Travel Risk, Severity, Barriers, and ITT

Perceived risk (PR) refers to an individual’s understanding of risks associated with any specific activity. It is a subjective evaluation or assessment by any individual regarding the potential negative outcomes or harmful consequences [

20]. It is a significant factor that predicts attitudes and behavioral intentions in travel decisions. Travelers perceive danger differently based on their knowledge, risk exposure, and risk tolerance levels [

21]). According to Egger and Neuburger [

22], travelers can safeguard or mitigate risks entirely or partially by assessing risks and gathering information. There is a concern about all types of risks occurring in the countries where international travelers choose to visit [

23]. Studies have shown that PR negatively affects individuals’ attitudes to travel and behavioral intentions [

21].

Perceived severity is the potential impact that a condition can have on an individual’s health and well-being. It is an important indicator for predicting an individual’s health-related behavior towards any situation. Different studies have shown that when individuals perceive disease as highly severe with potential complications, they undertake various preventive actions to avoid illness [

15]. In the context of air travel intentions, studies [

15] have revealed that the perception of a high risk of severe illness from COVID-19 significantly impacts air travel intentions.

Studies have shown that implementing effective quarantine measures can extensively decrease the spread of COVID-19 (37–88%) [

24]. The use of various safety measures by the government, including social distancing, temperature screening procedures, the presentation of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results, and regular disinfection, has had a negative impact on the transmission of infectious diseases [

25]. Nevertheless, Khan et al. [

26] argued that easing international air travel restrictions should be accompanied by robust preventive and control measures. Implementing personal protective interventions, particularly at airports, is crucial for reducing and controlling risks. Travelers’ post-crisis air travel intentions are generally affected by negativity bias [

27]. It was found that travel restrictions significantly affected the negative bias. Consequently, any travel restriction will negatively impact the perception of travel among customers. Therefore, travel’s credibility is undermined, negatively impacting post-crisis travel options [

28].

Therefore, the following hypotheses are developed.

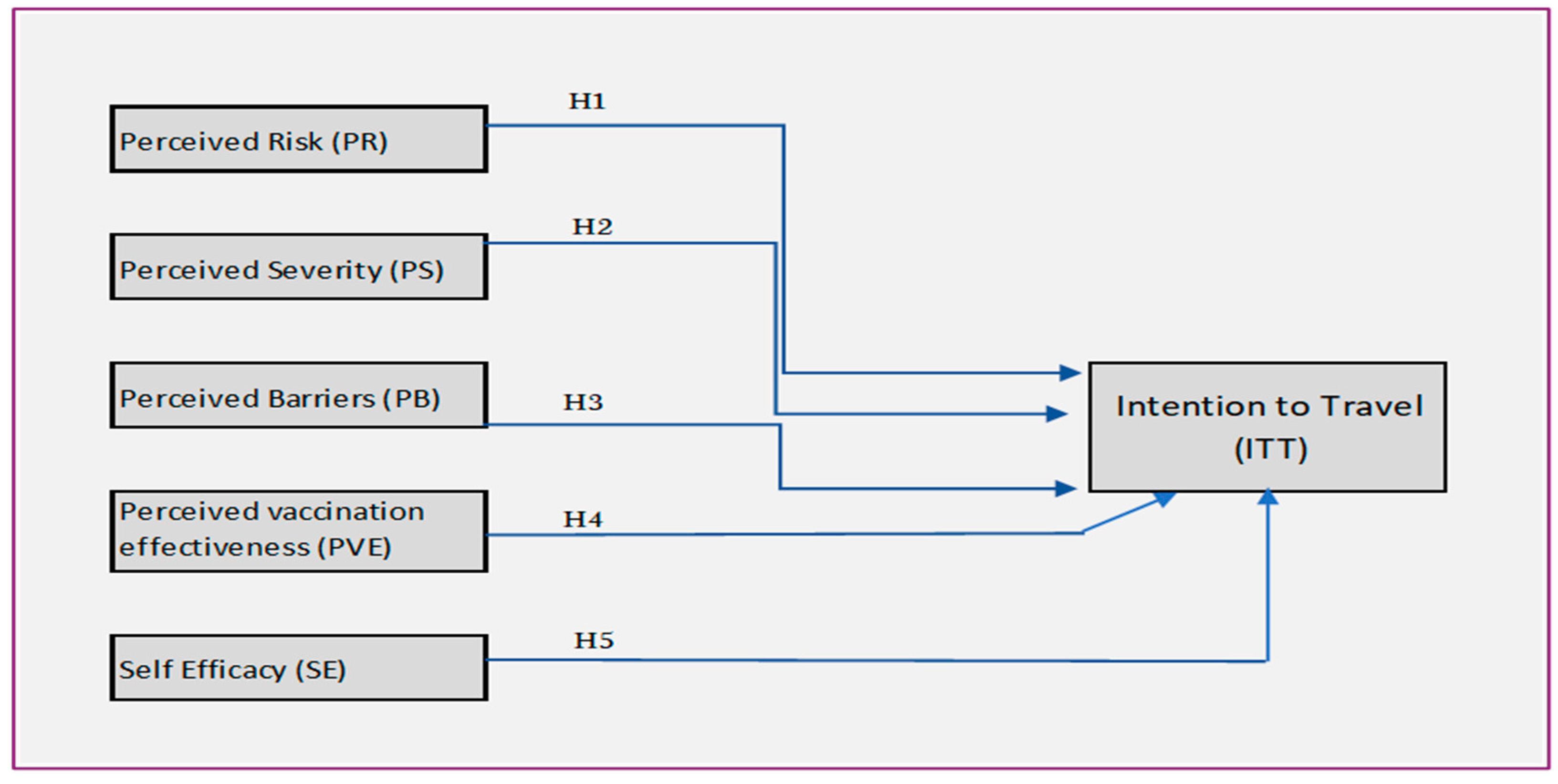

Hypothesis 1. Perceived risk (PR) negatively affects ITT.

Hypothesis 2. Perceived severity (PS) negatively affects the ITT.

Hypothesis 3. Perceived barriers (PB) negatively affect the ITT.

2.3. Perceived Vaccination Effectiveness (PVE), Self-Efficacy (SE), and ITT

Traveling to different locations can expose travelers to new diseases, making it necessary to get vaccinated before visiting areas affected by pandemics. However, traveler apprehension about vaccinations continues to be a roadblock [

29]. Vaccination helps establish herd immunity, which provides indirect protection against infectious diseases. However, there is concern about the “free rider” dilemma, where some individuals choose not to get vaccinated and benefit from those who have. Vaccine hesitancy is influenced by factors such as lack of knowledge, concerns about side effects and efficacy, and distrust in government. International health rules mandate certain vaccinations for entry into specific destinations, such as a yellow fever vaccination for travel to Ghana and meningococcal and polio vaccinations for pilgrims to Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 4. Perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness (PVE) are positively associated with individuals’ intention to travel (ITT).

Individuals’ beliefs are linked to their confidence in performing tasks or attaining desired outcomes successfully [

30]. Self-efficacy is essential in motivating individuals and influencing their behavior. They are influenced by past experiences, observations of others, receiving support or encouragement, and one’s physical and emotional well-being. Self-efficacy beliefs hold considerable sway over an individual’s motivation, decision-making, and dedication, and they influence important domains such as education, health behaviors, and personal advancement [

19]. This concept is considered a significant aspect of SCT, which refers to individuals’ belief in their ability to effectively plan and perform actions to accomplish specific goals [

19].

Researchers have been studying how tourists plan to take precautionary measures during travel. Many studies have examined self-efficacy in health and behavioral and travel contexts [

21]. Studies have shown that perceived self-efficacy influences the preventive behavior of individuals in health-related issues. Moreover, perceived self-efficacy has been found to positively affect attitudes and ITT [

31]. The present study examines the efficacy beliefs of tourists during the pre-trip stage of their behavior.

Therefore, the following hypothesis was assumed:

Hypothesis 5. Perceived self-efficacy (SE) positively affects the ITT.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the study.

3. Methodology

This study followed a quantitative research design. Data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Based on the existing literature, the questionnaire was adopted in its original form and modified to meet the research objectives. In this study, medical students across various specialties in Malaysia comprised the target population.

An online survey was conducted using Google Forms to collect information. The online survey link was shared in various medical students’ groups on Facebook to ensure that the respondents were drawn from the right population. Participants were assured of complete anonymity during data collection to reduce response bias and lessen the influence of social desirability. The data were collected between May and June 2023. Respondents, on average, took 12 min to complete this questionnaire, indicating an average level of engagement with the items. Respondents had to use their email ID, which restricted them from submitting duplicate entries. None of the participants were monetarily rewarded, a step that therefore decreased potential bias in responses that would be instigated by any offered incentive. This ensures the data quality and reliability. Finally, 398 valid responses were recorded after discarding incomplete responses for further analysis.

This study takes a novel approach not previously used in the literature by examining intentions to travel among medical students. The participants are chosen from the medical industry, which justifies this specific demography. The objective is to see if their travel intentions differ from those of individuals from non-medical backgrounds. The survey asked the respondents to make an overall assessment of their intention to engage in air travel during the post-pandemic period. The construct was meant to cover more of the general inclination or tendency to travel as opposed to specifying types of travel (e.g., domestic versus international, business versus leisure, or solo travel versus family travel). This orientation was chosen to align with the Health Belief Model framework by targeting the underlying psychological constructs influencing broad travel-related decision-making: thus, this is a helpful indicator of intention in general but would not differentiate among specific travel settings.

The study used constructs and measurement items gathered from the literature. Perceived risk and perceived severity were measured by four items [

23]. Similarly, self-efficacy and perceived barriers were measured by four items adopted from Huang et al. [

21]. The items were measured with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). In addition, the study included demographic variables, namely, gender and age.

Appendix A presents the measurement items and adopted sources.

PLS-SEM was used to estimate relationships between variables. PLS-SEM intends to maximize the explanatory variance of the dependent variable. It is a preferred approach when dealing with latent variables and multiple indicators and is an extensively used approach in tourism research [

32]. This approach involves two stages: measurement model assessment and structural model assessment [

33]. The mentioned stages are utilized to examine and analyze the suggested hypotheses. According to Hair et al. [

33], this study examined the measurement model’s internal consistency reliability, convergence validity, discriminant validity, and indicator reliability. Path coefficients, coefficients of determination, and predictive association measures were used to assess the presence of multicollinearity in structural models.

4. Results and Discussion

In support of the suggested structural model, descriptive statistics on the survey responses give further insights. The respective averages for the constructs were as follows (measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5):

Appendix B presents the summary statistics for the constructs. The low risk and severity perception scores intuitively correspond to a high confidence mean for vaccination effectiveness and self-efficacy, which conforms to their encouraging effect on intention to travel.

Exploratory correlation checks showed some interesting patterns suggestive of respondent profiles. Some participants consistently indicated high perceptions of risk and severity and low confidence in the vaccine (“worriers”). In contrast, others gave mixed responses, with moderate risk perception and high vaccine confidence and self-efficacy. This heterogeneity implies that the psychological responses toward post-pandemic travel are not homogeneous but clustered as latent orientations.

In terms of demographics, most of the respondents were male (61.6%), and the age group of 21 to 25 constitutes the majority (54.3%) of the respondents, followed by the age group below 20 (37.2%).

4.1. Measurement Model

This study followed the maximum likelihood approach, confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 1 presents the quality of the measurement model through the reliability of the indicators and convergent validity. The outer loading of the items ranged from 0.70 to 0.90, which met the suggested value (≤0.70) recommended by Hair et al. [

33]. The Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) values of the constructs range from 0.72 to 0.91 and from 0.82 to 0.94, respectively, exceeding the recommended value (≥0.70), indicating the high internal consistency and validity of each construct [

33]. Later, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were measured to examine convergent validity. The AVE values for all of the constructs exceed the acceptable level (>0.050) [

34] of convergent validity, as they range from 0.54 to 0.79.

Fornell and Larcker values also meet the criterion that the AVEs of the latent variables are higher than the square correlations between the latent and other variables [

34]. In addition, the HTMT values are below the suggested value of 0.85 [

33].

4.2. Structural Model

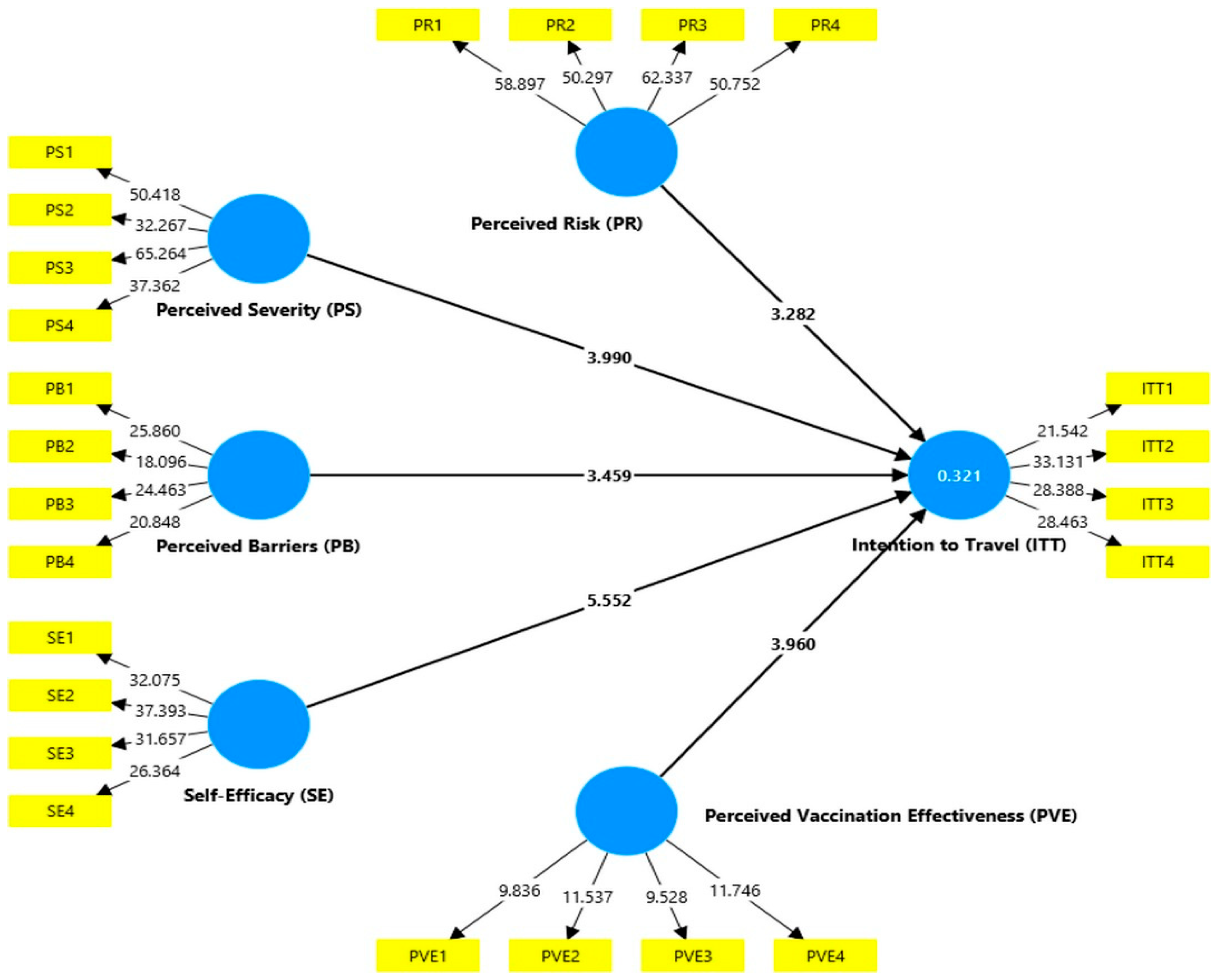

Figure 2 presents the structured model of the study, and

Table 2 summarizes the structural model’s results.

Table 2 shows that PR negatively affects the ITT (t = 3.195,

p = 0.001), which is statistically significant. Similarly, perceived severity (H2) and perceived barriers (H3) have significant negative effects on the ITT in the post-pandemic period. On the other hand, Hypothesis 4 and Hypothesis 5 demonstrate that vaccination effectiveness and self-efficacy, respectively, have positive effects on the ITT.

The predictive capability of the structured model was from weak to moderate, considering the values of R

2, Q

2, and f

2 from

Table 3. As Hair et al. [

33] indicated, an R

2 value of 0.25 is considered weak, 0.50 is moderate, and 0.75 is substantial. In this case, the threshold values are higher than those of this research but do not reach the substantial measure, thus depicting that the model showcases weak to moderate predictive power.

The fact that the Q2 values are greater than zero confirms its predictive relevance, which means this model is not only considered explanatory but can also efficiently predict the dependent variables. Analogous to this are the f2 effect sizes for predicting constructs, wherein some exert a small effect while others exert a far greater effect, therefore providing further assurance that the model must be seen overall as moderately effective.

Nevertheless, it ensures some fair explanatory and predictive accuracy. These results imply that the psychological variables considered in this study still play a definite role in post-pandemic intention to travel, rendering the conceptual model a moderate ability to predict, with reasonable practical implications for academic and industrial relevance.

4.3. Discussion

This study explores how various psychological factors influence individuals’ intentions to resume air travel after the pandemic, highlighting their complex interplay. Because of uncertainties in health and safety measures and potential exposure to infectious diseases, the PR decreases the ITT. The result demonstrates that PR and PS negatively affect the ITT. The negative relationship, or the coefficients (−0.163, −0.220), indicates that the ITT decreases as PR and barriers increase. Similarly, the results for individuals with a higher PS exhibit lower ITT. It indicates that the ITT decreases as individuals perceive the severity of the potential consequences of air travel and assess the potential drawbacks regarding barriers such as air travel, travel restrictions, expenses, and unforeseen costs. Recent studies during the pandemic conducted by Huang et al. [

21], Das and Tiwari [

15], and Golets et al. [

23] also reached the same conclusion regarding ITT. The present study’s conformity reveals that individuals are sensitive to PR associated with air travel even after the pandemic or the post-pandemic period. These emphasize the importance of individuals’ subjective evaluations of potential risk to travel decisions. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of effective risk mitigation strategies and transparent communication by aviation authorities and airlines.

The positive coefficients of perceived vaccination effectiveness and self-efficacy demonstrate a positive relationship to travel. The results suggest that when individuals perceive vaccination as effective, they are more inclined to travel. This highlights the importance of vaccination and immunization programs in promoting confidence and normalizing travel behavior. In the same way, individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy or confidence in overcoming obstacles and the ability to cope with the challenges of new circumstances exhibit a stronger ITT [

1,

6,

30]. This highlights the role of individuals’ perceived capability in alleviating the obstacles in the changed scenario. From the study result, it is explored that the effect of self-efficacy is higher than the negative effect of PR, PS, and PB on the ITT.

The study’s findings affirm the hypothesized relationships between psychological constructs and intention to travel and align with the health belief model. According to this theory, health-related behaviors are influenced by individuals’ perceptions of susceptibility, severity, benefits, and self-efficacy. The negative association of perceived risk and perceived severity validates the model since increased perceptions of health threats and travel uncertainties dominate the travel intentions, which is consistent with prior research [

15,

21,

23].

In this study, an important insight is provided by the focus on medical students, who have higher levels of health literacy and probably much more confidence in health interventions with each other, such as vaccination. Hence, this is an interesting target group to study to see how those who are better informed about medical risks and protective behaviors respond to travel-related decisions post-pandemic. However, medical students may not represent the general population. Previous research performed in general populations often reveals low confidence in vaccines and weaker self-efficacy, with opposing higher perceptions of risk concerning travel [

15,

21,

23,

35], so it could be that much of the higher self-efficacy and confidence reported by medical students in the present study can be seen as a direct result of training and familiarity with health interventions.

These differences, cautioning against generalization of the results beyond the medical student population, make clear the strength of research in highlighting how risk and confidence are addressed by this health-literate population when forming travel intentions. Such insight can provide a baseline to compare it to other populations and to guide strategies for targeted communication: while medical students may be fairly confident already, messaging for the general population may need to particularly emphasize affirming self-efficacy and trust in interventions.

5. Contributions and Limitations

This study bridges two influential theories, SCT and HBM, to enhance the understanding of health-related behaviors after the pandemic. By integrating HBM and SCT, this study sheds light on the interplay between health risk perception, individual beliefs, and motivation. This holistic approach helps to grasp why medical students make specific choices related to travel during the post-pandemic period.

In addition, this study stresses the importance of effective marketing strategies to prioritize safety precautions at airports and during flights. Utilizing the HBM, this study validates how the medical student’s health behavior regarding perceived risk affects travel decisions or intentions. The findings on the perceived severity, self-efficacy, and efficacy of vaccination can inform the design of communication and promotion campaigns to increase travelers’ confidence in flying. It is essential to comprehend how travelers behave in light of the increasing vaccination rates worldwide and the opening of borders, since their ITT will stimulate the airline industry and tourism sectors. Airlines and tourism sectors can strategize effectively by aligning their marketing and business approaches with consumer demand.

Limitations and Future Works

Despite these contributions, this study has several limitations. Several limitations of this study warrant being noted. First, the sample in the study contained only Malaysian medical students. While this is a target group, considering their health literacy, they may view the effectiveness of vaccination, self-efficacy, and risk perception in ways that differ systematically from most people. This limitation constrains how generally applicable the findings are, thus making it necessary for other studies to replicate this kind of study with a more diverse sample, including groups in both non-medical studies and the general traveling population.

Second, although the sample contained male and female respondents, with 61.6% identified as male, and was mainly composed of individuals aged between 21 and 25 (54.3%), followed by those under 20 (37.2%), further demographic information was lacking. The present study did not consider the role of age or gender on perceived risk and perceived severity that may influence the ITT during the post-pandemic period. The absence of any detailed balance tests about socioeconomic background, rural-urban place of origin, or family status makes it impossible for us to fully discard sample-selection effects. Being a voluntary participation study, this raises the likelihood that individuals who are more confident about their health or have more interest in travel opted to complete it.

In addition, this study is based on convenience sampling, which may have potential for selection bias. This implies that the findings may not be fully generalizable to the broader population of Malaysian medical students. Future studies can use stratified sampling to include samples from different medical colleges in Malaysia, thereby increasing representativeness and decreasing sampling bias.

The study assessed the general intention of traveling by air without further distinguishing between domestic and international trips, business and leisure purposes, or traveling solo versus with family. Being as such, it is safe to assume that respondents weigh risks and benefits differently across these contexts; for instance, they may be more likely to travel domestically for an essential purpose than internationally for leisure with family members.

Despite these limitations, evidence is added by the study in regard to the psychological processes directing travel intentions in the post-pandemic context, particularly with health-literate people. Future endeavors should broaden the sample base and include other demographic comparisons to enhance external validity.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 outbreak has resulted in a dramatic drop in international and domestic flights around the world. In the literature, travel intention studies explored the ITT among general tourists based on behavioral intentions. However, the relationship between psychological constructs that affect individuals’ mindsets and confidence and travel intention is missing. This study aims to investigate medical students’ ITT in light of behavioral intentions like travel risks, travel barriers, travel severity, and the psychological construct of self-efficacy. The findings revealed that perceived risk, severity, and barriers significantly negatively impact travel intentions during the post-pandemic period. Conversely, self-efficacy and perceived vaccination effectiveness positively influence travel intentions. The aviation industry is recovering after the borders are fully and freely reopened. However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will affect consumer travel behavior, and changes in consumption habits will impact the aviation industry. Therefore, the study findings would help different stakeholders to develop policies to attract travelers during this pandemic.

7. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study is not experimental research and did not involve gender, animals, human embryos, or geological material. The respondents were students pursuing medical studies in Malaysia. Data were collected using Facebook, where the survey link was posted in the various medical students’ groups. The methods used in this study adhered to all applicable guidelines and regulations.