Abstract

In Melbourne, Australia, strict ‘lockdowns’ were implemented in 2020 to suppress COVID-19, significantly disrupting daily life. Young people (<18 years) with medical conditions have an elevated risk of mental health problems and may have been disproportionately affected by the distress associated with the COVID-19 restrictions. To investigate this, we conducted a single-site, longitudinal cohort study involving the parents of 135 children and adolescents with medical conditions. Using an adapted version of the CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS), parents rated their child’s mental health, activities and healthcare experiences pre-COVID-19 (retrospectively), during lockdown and 6 months post-lockdown. General linear mixed models revealed that mental health symptoms, including anxiety, fatigue, distractibility, sadness, irritability, loneliness and worry, were higher during lockdown compared to pre-COVID-19. Notably, anxiety, sadness and loneliness remained elevated 6 months post-lockdown. Covariates such as older child age, increased parent stress and child screen time contributed to greater mental health difficulties. While most mental health symptoms resolved post-lockdown, the persistence of anxiety, sadness and loneliness highlights the need for ongoing clinical monitoring for young people with medical conditions during periods of community stress and restrictions.

1. Introduction

The highly infectious nature and significant health and mortality consequences of COVID-19 led to global policies of social distancing, lifestyle, education and work restrictions, including stay-at-home orders or ‘lockdowns’ to suppress infection rates. In Melbourne, Australia, residents experienced their first lockdown in March 2020 with most restrictions remaining until the end of October 2020 [1]. Melbourne had the most consistently stringent lockdown in Australia across the 2020–2021 period and 170 days of school closures, double that of any other Australian state or territory [1].

COVID-19 lockdowns caused major upheaval in the lives of children and adolescents (i.e., ‘young people’), with stay-at-home orders including remote learning, no face-to-face interactions with peers and the cancellation of extra-curricular activities. The mental health symptoms of young people reported during the COVID-19 pandemic and heightened restrictions such as times of remote learning include anxiety, behavioral difficulties, depression, conduct problems, inattention and hyperactivity [2,3,4].

To date, most research into the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused on young people without medical conditions [5]. However, young people with medical conditions have an elevated risk of mental health problems [6,7], experienced additional stressors associated with changes to clinical care due to restrictions (i.e., telehealth for appointments) and are likely to have higher parental stress [8]. Therefore, it was expected that the distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic would be magnified.

Research shows that young people with medical conditions were vulnerable to psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic [9,10,11], although results have varied, depending on the type of condition. For example, young people with respiratory problems and impaired immunity may experience heightened anxiety over concerns that COVID-19 could cause severe illness [9,10]. Young people with medical conditions including asthma, allergies, heart problems, obesity, kidney problems, immune disorders and cancer experienced more mental health symptoms than young people without medical conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. There is a paucity of research investigating whether young people with medical conditions that require ongoing care but without a condition that may increase the complications of COVID-19 experience a rise in psychological distress. The available studies have reported high levels of anxiety and behavioral difficulties in young people with functional abdominal pain disorders during COVID-19 restrictions [11].

It has been established that the pandemic had a negative impact on young people’s mental health; however, few studies have investigated whether these issues persisted or subsided as restrictions were lifted [3]. A study of adolescent mental health 6 months after restrictions reported significant stress levels in 25% of the sample. However, the ability to understand change from pre-existing stress levels is limited without comparative data [12]. Another study on families with young children found a peak in behavioral difficulties during lockdown, followed by a decline as restrictions eased [13]. Further, young people in Victoria, Australia, endured one of the longest lockdowns in the world, and therefore, their experience is different to young people in both other Australian states, as well as international countries [14].

The COVID-19 pandemic added significant stressors for parents, including financial strain and the challenges of balancing work from home with supporting their children’s remote learning. For parents of young people with medical conditions, it resulted in higher levels of anxiety, depression and physical stress symptoms compared to parents of healthy children [8,9]. Understanding parental stress during the pandemic is crucial, as it has been linked to increased mental health symptoms in young people [13,14].

This study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people with medical conditions by providing longitudinal data on mental health symptoms and activities and to investigate whether there was a return to pre-COVID levels. The study also examined the influence of parent and child factors on the outcomes. The aims of the study were as follows: (1) to examine the mental health, activity change and healthcare experience of young people with a medical condition across three timepoints prior to lockdown, during lockdown and 6 months after lockdown and (2) to examine whether demographic/family variables and screentime predict mental health symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected as part of a prospective, longitudinal cohort project, ‘COVID Resilience’, conducted at a single site. The inclusion criteria for the project were as follows: (i) 5–17 years old; (ii) a diagnosis of a medical condition (chronic constipation, neurofibromatosis type 1 [NF1] or cleft palate); (iii) currently receiving outpatient care at the RCH; (iv) attended an outpatient appointment in the 12–24 months prior; and (v) a parent/caregiver with sufficient English fluency to complete questionnaires. Participants were excluded if they experienced an inpatient admission during lockdown.

2.1. Measures

The surveys were delivered online via REDCap 14 [15]. The COVID-19 Wellbeing and Mental Health Survey for Children and Adolescents (Parent/Caregiver version) is a modified version of the CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS), developed to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals across mental, behavioral and physical health domains [16]. The questionnaire captures pre-existing risk and protective factors, as well as health outcomes and behaviors [16]. We adapted the CRISIS tool to seek specific information for our study population. Parents rated their children’s mental health symptoms (anxiety, fatigue, distractibility, sadness, irritability, loneliness and worry) using a 5-point Likert scale (1, none/not at all, to 5, extreme). Parents rated their stress level between 1 (not stressful) and 10 (very stressful). Parent education was categorized as follows: (1) some high school, (2) high school diploma/trade certificate/apprenticeship, (3) bachelor’s degree, and (4) postgraduate degree. Information was collected on activities, and parents were asked to rate their healthcare experiences.

2.2. Procedure

Clinicians and research assistants screened patients for eligibility using the hospital’s electronic medical record. The parents of young people who met the inclusion criteria were sent an invitation letter, with details about the study, from their respective clinical department. Families who did not opt out were contacted by phone to further explain the study and determine whether willing families were emailed an electronic consent and link to a survey in REDCap. The first data wave was collected during the lockdown period of June–October 2020, and parents were asked to provide their ratings at Time 1 (T1), 3 months prior to lockdown, and Time 2 (T2), the past month during lockdown. Time 3 (T3) data were collected between December 2020 and April 2021, 6 months after their baseline response, when restrictions had eased.

The study took place in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia’s second-largest state, which experienced an 18-week lockdown in 2020. During the strictest phase of the lockdown, lasting over 3 months, individuals were only allowed to exercise outside their homes for 1 h per day, and one household member could go out to purchase essential items. A curfew was in effect from 8pm to 5am, and travel was restricted to a 5 km radius from home. Visits from outside individuals were prohibited, including extended family and friends. Schools were closed, except for young people whose parents were essential workers or those who were unable to learn from home safely. Medical appointments were primarily conducted via telehealth. Playgrounds, cultural and recreation centers, face-to-face organized sports and recreation activities (e.g., music lessons, etc.) were either closed or moved online.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported for both child and parent characteristics. Frequencies were reported for child and adolescent activities and healthcare usage. In line with other studies of children with medical conditions [10], the sample was analyzed as a homogeneous group. The dependent variable was mental health symptoms (anxiety, fatigue, distractibility, sadness, irritability, loneliness and worry). Model diagnostics confirmed that model assumptions (e.g., normality and homogeneity) were met. The independent variable, time, was entered as a categorical variable with three levels: 3 months pre-COVID (T1), during COVID lockdown (T2) and 6 months post-lockdown (T3). General linear mixed models with restricted maximum likelihood and an identity link function were used to evaluate differences in child mental health symptoms at T2 and T3 relative to T1 (reference level). Model covariates included child age, sex, parental stress, education level and child screentime. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05, with all analyses conducted in Stata/SE 18.5 [17].

3. Results

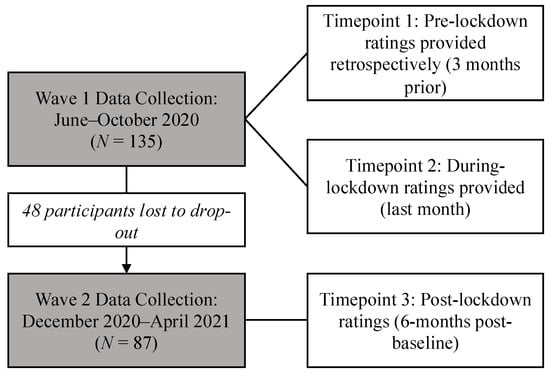

Of 297 families contacted; 177 consented, of which 135 families participated at T1 and T2 and 87 families (64.1% retention) participated at T3 (Figure 1). Due to local privacy laws, we are unable to report any information on families who did not participate. Table 1 lists the demographic information of the group. The sample consisted of young people diagnosed with colorectal disorders (n = 32), NF1 (n = 43) and cleft palate (n = 60).

Figure 1.

Data collection waves and participant drop-out.

Table 1.

Group demographics.

3.1. Mental Health Symptoms During Lockdown (T2)

General linear mixed models (LMM; Table 2) were used to evaluate mental health symptoms, and they revealed that parents reported increased child anxiety, fatigue, sadness, distractibility, irritability, loneliness and worry during lockdown than at 3 months prior to lockdown (T1; p-values < 0.05).

Table 2.

General linear mixed models of mental health symptoms predicted by time and covariates.

3.2. Mental Health Symptoms Post-Lockdown (T3)

Child anxiety, sadness and loneliness were greater at 6 months post-lockdown compared to 3 months pre-lockdown (b = 0.32, 95%—CI 0.11, 0.57; b = 0.58, 95%—CI 0.38, 0.78; and b = 0.23, 95%—CI 0.05, 0.41). No significant effects were detected for fatigue, distractibility, irritability or worry.

3.3. Mental Health Symptoms and Covariates

We examined whether demographic, family factors or child screentime contributed to mental health symptoms. Child sex and parent education did not significantly contribute to child mental health symptoms. For each increment in age (5 years), there was a significant increase in worry symptoms (b = 0.15, 95%—CI 0.01, 0.28). Higher parent stress was associated with greater distractibility, sadness, irritability and loneliness (p-values < 0.05). Higher screentime was associated with both increased sadness and worry (b = 0.06, 95%—CI 0.01, 0.12; b = 0.06, 95%—CI 0.01, 0.10).

3.4. Child and Adolescent Activities

Parents were asked to indicate whether the amount of time their child participated in their usual pre-COVID activities had changed during lockdown. The results indicated that, during lockdown compared to pre-lockdown, there was increased time on screens, including computer games/screens/TV (58.5%), arts and crafts (up 49.6%), sports/active games (up 45.2%) and creative play (up 34.8%). The proportion of children spending more than 4 h per day using screens increased from 10.4% pre-lockdown (T1) to 47.4% during lockdown (T2). At 6 months post-lockdown (T3), this reduced to 18.2%.

3.5. Healthcare

Parents were asked questions relating to the healthcare received by their child at Time 2 (during lockdown) and how it compared to pre-COVID-19 services in terms of quality and quantity. During lockdown, 33.5% of parents indicated they had difficulty accessing healthcare for their child. Regarding the quality of their child’s healthcare during lockdown, 56.3% of parents indicated that they had experienced no change relative to pre-COVID-19 services, 12.6% indicated that healthcare quality was ‘a little worse’, and 7.8% indicated that health care quality was ‘a lot worse’; 6.0% of parents indicated that the healthcare quality received by their child had improved during this time. Relative to pre-COVID-19 arrangements, 47.3% of parents indicated no change, 33.5% indicated that they received ‘a little less’ and 13.8% indicated that they received ‘a lot less’ in the quantity of healthcare services received by their child during lockdown, and 5.4% indicated the quantity of healthcare received by their child increased. Regarding the quality of telehealth care compared with face-to-face care, a majority (55.2%) indicated that they preferred face-to-face, a large minority (33.1%) indicated that telehealth was no different to face-to-face, and a small minority (11.7%) indicated a preference for telehealth appointments.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people with medical conditions. The main finding was that young people’s mental health was negatively impacted during the COVID-19 lockdown and that the impacts were lasting, with some symptoms persisting 6 months after lockdown. The peak in mental health symptoms in lockdown is consistent with research on typically developing young people [2,3,4] and studies on young people with chronic respiratory disorders [9,10]. This study was focused on the mental health symptoms of young people without an obvious vulnerability to health complications if they contracted COVID-19. While there is limited research for comparison, it is consistent with the high levels of anxiety reported by young people with functional abdominal pain disorders during COVID-19 restrictions [11].

During the COVID-19 lockdown, the mental health symptoms of anxiety, fatigue, sadness, irritability, distractibility, loneliness and worry all increased in comparison to pre-COVID ratings. Anxiety, sadness and loneliness in young people remained elevated 6 months after lockdown, which aligns with findings from a UK report on children with special education needs and neurodevelopmental disorders [18]. Limited research has provided information on the long-term consequences of the pandemic [5]. A Canadian study reported that 25% of children continued to experience significant stress levels 6 months after the initial restrictions [11]. Interestingly, these findings contrast with other research that observed a decrease in behavioral difficulties in young children as restrictions eased [12].

Factors associated with the higher reporting of mental health symptoms were identified. Increased age was a predictor, with older children and adolescents reporting higher mental health symptoms, likely due to increased worry and the heightened impact of social isolation and disrupted schooling during lockdowns, with peer interactions particularly important for this age group [19,20]. The importance of parent mental health on the wellbeing of young people was evident, with increased parent stress predicting higher distractibility, sadness, irritability, and loneliness in young people. This is consistent with research linking maternal depression and emotional/behavioral problems in children with medical conditions in the COVID pandemic [12]. Indeed, the parents of young people with medical conditions may require additional support, as they are more vulnerable to mental health problems compared to the parents of children without medical conditions [8].

During the lockdown, children engaged in remote schooling and lacked face-to-face peer interaction. Their leisure activities shifted to home-based options such as arts and crafts, home-based sports, and creative play. Notably, there was an increase in physical activity, which is generally associated with better mental health outcomes [3,19]. However, screen time also significantly increased, and it included the use of computers for remote learning and games, social media, and TV. The number of young people with screen time exceeding 4 hours a day increased during the lockdown, and this high usage persisted at the 6-month follow-up. The addictive nature of devices and potential negative consequences raises concerns [21]. While young people are familiar with digital communication, face-to-face peer interaction remains an important factor in their social and emotional wellbeing [3]. Higher screentime at the 6-month follow-up was associated with increased sadness and worry. While more specific information on the type of screen time was not collected, details on this may have been valuable, given an association found between increased social media use and depressive symptoms [20].

During lockdown and many months after, medical appointments were moved to telehealth. Telehealth increases accessibility, and it continues to be used much more in healthcare than prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most families in this study reported telehealth to be less satisfactory than face-to-face consultations, and our study found lower satisfaction than a study of children with epilepsy [22]. However, at the 6-month timepoint, more parents were satisfied with both the quality and quantity of telehealth, suggesting that families were becoming accustomed to telehealth for medical appointments.

There were limitations to the study. These include the fact that the pre-lockdown information was collected retrospectively, with the associated risk of parent retrospective reports being overly positive. We did not include self-reports, and ratings of child and adolescent function may have been confounded by parent coping and stress. Not all families enrolled participated at Time 3. There was possibly an attrition bias with families who remained in the study differing in a systematic manner to those who dropped out. Families were sent the surveys to the same email throughout and asked to answer for the same child, but there was the possibility of a different parent answering the survey if they shared the email address or of completing it for a different child if they became confused. We did not compare young people with a medical condition to a control group of typically developing children, as we were particularly focused on how children with medical conditions managed the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the study designed for the participants to be their own control in the statistical analysis.

The implications of the study identified that the COVID-19 pandemic has had multiple negative impacts on children and young people with medical conditions, including mental health. Our findings support the need for clinicians to monitor the mental health status of children with medical conditions and consider the quality of telehealth delivery for clinical services. Further research into the role of activities to mental health is warranted, with the research suggesting that those who are more active had better mental health and that screentime usage did not dissipate after the COVID lockdown finished. Parent mental health has an impact on children’s mental health, and interventions to help parents should be made more available in times of pandemic restrictions.

5. Conclusions

This single-site study in Victoria, Australia, revealed that young people with medical conditions experienced heightened mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown, with many symptoms, such as anxiety, sadness and fatigue, persisting for 6 months post-lockdown. Factors such as age, parent coping and screentime usage contributed to young people’s mental health symptoms. These findings highlight the importance of ongoing mental health monitoring and tailored interventions during extended periods of disrupted functioning, particularly in regions with prolonged restrictions, to mitigate long-term impacts on this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

L.M.C.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision and project administration.; V.A.: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing and supervision.; S.H., D.G. and B.C.: formal analysis and writing—review and editing.; C.C., N.A. and R.P.: methodology, project administration, data curation and writing—review and editing.; N.K., E.B., J.M.P., K.H., N.M., C.K., G.C., M.T., I.H., P.L.H. and S.K.: conceptualization, methodology and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Vanguard Foundation, the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the Victorian Infrastructure Operating Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Melbourne (HREC 64840) on 10 June 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.M.C., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Edwards, B.; Barnes, R.; Rehill, P.; Ellen, L.; Zhong, F.; Killigrew, A.; Gonzalez, P.R.; Sheard, E.; Zhu, R.; Philips, T. Variation in Policy Response to COVID-19 Across Australian States and Territories; Blavatnik School of Government: Oxford, UK; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, C.; Shum, A.; Pearcey, S.; Skripkauskaite, S.; Patalay, P.; Waite, P. Young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicouri, G.; March, S.; Pellicano, E.; De Young, A.C.; Donovan, C.L.; Cobham, V.E.; Rowe, A.; Brett, S.; Russell, J.K.; Uhlmann, L. Mental health symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauhanen, L.; Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Lempinen, L.; Peltonen, K.; Gyllenberg, D.; Mishina, K.; Gilbert, S.; Bastola, K.; Brown, J.S.; Sourander, A. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobham, V.E.; Hickling, A.; Kimball, H.; Thomas, H.J.; Scott, J.G.; Middeldorp, C.M. Systematic review: Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegethoff, M.; Belardi, A.; Stalujanis, E.; Meinlschmidt, G. Association between mental disorders and physical diseases in adolescents from a nationally representative cohort. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wauters, A.; Vervoort, T.; Dhondt, K.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Morbée, S.; Waterschoot, J.; Haerynck, F.; Vandekerckhove, K.; Verhelst, H. Mental health outcomes among parents of children with a chronic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of parental burn-out. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademhan Tural, D.; Emiralioglu, N.; Tural Hesapcioglu, S.; Karahan, S.; Ozsezen, B.; Sunman, B.; Nayir Buyuksahin, H.; Yalcin, E.; Dogru, D.; Ozcelik, U. Psychiatric and general health effects of COVID-19 pandemic on children with chronic lung disease and parents’ coping styles. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 3579–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawke, L.D.; Monga, S.; Korczak, D.; Hayes, E.; Relihan, J.; Darnay, K.; Cleverley, K.; Lunsky, Y.; Szatmari, P.; Henderson, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth mental health among youth with physical health challenges. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strisciuglio, C.; Martinelli, M.; Lu, P.; Lev, M.R.B.; Beinvogl, B.; Benninga, M.A.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Nastro, F.F.; Nurko, S.; Pearlstein, H. Overall impact of coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in children with functional abdominal pain disorders: Results from the first pandemic phase. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 73, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, K.D.; Exner-Cortens, D.; McMorris, C.A.; Makarenko, E.; Arnold, P.; Van Bavel, M.; Williams, S.; Canfield, R. COVID-19 and student well-being: Stress and mental health during return-to-school. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Hacker, A.; Bar-Shachar, Y.; Egotubov, A.; Uzefovsky, F.; Gueron-Sela, N. Trajectories and associations between maternal depressive symptoms, household Chaos and Children’s adjustment through the COVID-19 pandemic: A four-wave longitudinal study. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, D. Josh Frydenberg Says Melbourne is the World’s Most Locked Down City. Is That Correct? Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2021. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-25/fact-check-is-melbourne-most-locked-down-city/100560172 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, K.; Milham, M.; Stringaris, A.; Bromet, E.; Colcombe, S.; Zipunnikov, V. The Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS). Available online: www.crisissurvey.org (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Stata/SE 18.5; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2024.

- Shum, A.; Skripkauskaite, S.; Pearcey, S.; Waite, P.; Creswell, C. Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health: One Year in the Pandemic; Co-Space Study: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 52, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, C.; Muggeridge, A.; Cross, J.H. The perceived impact of COVID-19 and associated restrictions on young people with epilepsy in the UK: Young people and caregiver survey. Seizure 2021, 85, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).