Abstract

This study aims to explore the experiences of frontline hospital nurses over 18 months of struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic. The qualitative thematic analysis method was applied. Twenty-three nurses from nine tertiary hospitals in Israel were interviewed using semi-structured interviews via the ZOOM platform between August and September 2021. Interviews were video recorded and transcribed verbatim. Trustworthiness was assured by using qualitative criteria and the COREQ checklist. Results: Both negative and positive experiences were reported: threat and uncertainty along with awareness of their important mission; anxiety and helplessness alongside courage and heroism. Personal management strategies emerged: regulating overwhelming emotions and managing work–life balance. Team support emerged as the most meaningful source of nurses’ struggle with the pandemic. A sense of intimacy and solidarity enabled the processing of the shared traumatic experiences. Conclusions: A deeper understanding of nurses’ experiences through the pandemic was gained. Informal peer support has proven effective in struggling with the events. Formal interventions, such as affective–cognitive processing of traumatic events, need to be integrated into practice. Healthcare policymakers should promote better support for caregivers, which will contribute to their well-being and impact the quality of care they provide.

1. Introduction

Frontline nurses in hospitals are trained and experienced in caring for patients in routine and emergencies. However, the COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented challenges to the international nursing community, which was not adequately prepared. The professional nursing literature is depleted with research studies aiming to understand the impact of the pandemic on the nursing workforce [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Although we have learned a lot since the outbreak, several issues should be further explored for future lessons about major traumatic events. For example, what were the strategies that contributed to nurses’ struggles versus obstacles or shortcomings? Were there also gains for nurses and the nursing profession, in addition to the adverse consequences? The current study adds to the existing body of knowledge by providing a holistic view of the phenomenon from the perspective of frontline nurses.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline nurses experienced both primary and secondary traumatization. Secondary traumatization refers to the stress response of people exposed to others who are suffering or undergoing traumatic events without having experienced that traumatic event themselves [8]. Nurses, as caregivers, are witnessing traumatic events as part of their professional role. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed nurses to intensely traumatic experiences that evoked some posttraumatic symptoms such as insomnia, intrusive thoughts, anxiety, and depression [9]. The pandemic has raised awareness of this phenomenon that has not been adequately addressed in nursing.

Nursing research studies during the COVID-19 pandemic are mainly focused on the adverse mental, emotional, and physical impact of the pandemic on nurses. The findings included thoughts and feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, depression, fear, frustration, anger, helplessness, sadness, emotional exhaustion, withdrawal, isolation, intrusive thoughts, burnout, feeling unsupported, and work-family stress [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Evidence of positive thoughts and feelings was also identified, such as feeling valued, professional satisfaction, empowerment, high resilience, flexibility, and the ability to reinvent the service [7,17,18].

A literature review revealed a variety of management strategies and resources utilized by healthcare workers and nurses during the pandemic. According to a meta-analysis of 18 studies, the effects of yoga and music-based interventions were the most prominent mind-body interventions among healthcare workers during the pandemic era [13]. Frontline nurses reported that writing letters and diaries, breathing relaxation, mindfulness, and music meditation helped improve their emotional state [18,19]. Nurses also reported a range of self-care strategies, including physical exercise, diet, and increased attention to infection control at home and work [20]. Moreover, the pandemic provided nurses with an opportunity to re-evaluate the important elements of their lives and understand the meaning and value of things. Nurses have gained a positive perspective on life that has led to personal and professional growth [7].

Support and acknowledgment from family, friends, patients, peers, the public, and the state were crucial for strengthening nurses’ resilience, motivation, coping strategies, and professional image [15,21,22]. Several studies reported that hospital leadership communication was transparent, effective, and timely during the pandemic [4]. Others found evidence of inadequate organizational support that led nurses to feel uncared for and unsafe, with no one taking responsibility to fulfill their needs [14,19].

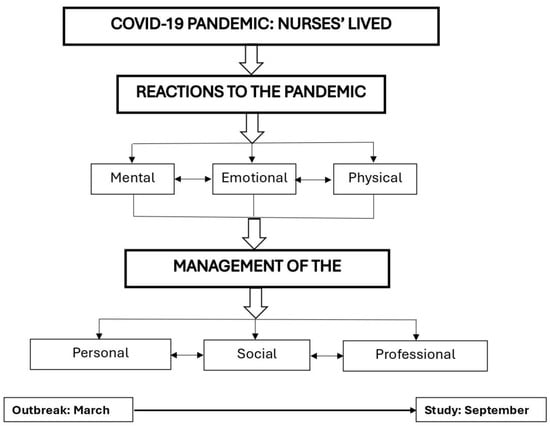

In summary, nursing studies provided empirical evidence of how the various management strategies helped nurses manage mental, emotional, and physical hardship throughout the pandemic. Most of the studies focus on the pandemic’s adverse impact on nurses, with recommendations to be better prepared for the future. However, the results are somewhat sporadic and vague, with no integrative theoretical framework that helps to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. The current study addresses these gaps by incorporating the positive changes and gains as a result of the struggle with the pandemic while presenting a comprehensive theoretical framework. The analysis unveiled the interrelatedness among all aspects of how nurses responded to the COVID-19 pandemic: mentally, emotionally, and physically. Moreover, it revealed how the way nurses responded impacted their approach to managing their personal, social, and professional lives.

This study aimed to explore the experiences of frontline hospital nurses during their struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic, from their perspectives. The study objectives were to (1) investigate nurses’ positive and negative aspects of the struggle with the pandemic; (2) explore their mental, emotional, and bodily reactions to the pandemic; (3) gain insights about the interrelations among the reactions (e.g., how their perceptions influenced their bodily and emotional reactions); and (4) disclose nurses’ ways of managing the challenges posed by the pandemic in various domains of their lives, including personal, social, and professional.

2. Materials and Methods

The qualitative thematic analytic method was applied as an approach to analyzing data about hospital nurses’ experiences during the pandemic. Thematic analysis, according to Braun and Clarke [23], is a method that involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within data, providing rich interpretation and conceptualization of the research topic. The analysis is driven by research questions and involves six phases: familiarizing oneself with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming the themes, and finally producing the report. The analysis should go beyond mere description, making a clear argument about the research question, supported by relevant data extracts. The 32-item checklist of consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) was used (Supplementary File S1).

2.1. Study Setting and Recruitment

A purposeful sampling strategy was used in this study to recruit hospital registered nurses who had directly cared for patients with COVID-19 and reflected the nursing workforce during the pandemic in Israel. Initially, nurses in post-graduate programs and alumni were recruited by email announcements. Thereafter, we used snowballing with their colleagues as well as social media (e.g., Facebook and nursing forums).

We used theoretical saturation as the guiding principle for assessing the appropriateness of purposeful sampling and sample size. We started with concurrent interviews, analysis, and a literature review that enabled us to identify the initial themes, categories, and subcategories. More selective data were collected from the nurse participants to uncover the properties of the categories while keeping in mind the study’s aim and objectives.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included male and female registered nurses, with varied professional experiences and from different backgrounds and cultures, who experienced direct care of COVID-19 patients in hospitals during the pandemic. Exclusion criteria included community nurses and nurses with no professional experience in direct caring for COVID-19 patients.

2.3. Data Collection and Abstraction

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all interviews were conducted face-to-face using the ZOOM video platform, with interview settings and timings scheduled at participants’ convenience in a quiet, private place. Two pilot interviews were conducted to test and refine the semi-structured interview guide, with field notes taken during and after the interviews. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview guide in Hebrew for 60–90 min. All interviews were visually recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted by the principal nurse investigator and the second author, a qualitative researcher, supported by a research team of four experienced researchers in the field of healthcare. The interviews were conducted during August–September 2021. The process of data collection and analysis continued until saturation was obtained, and no additional new information, themes, or theoretical insights were added to enhance the full understanding of the participants’ perspectives.

2.4. Data Analysis

We employed the thematic analysis method for this study [23]. The analysis process occurred concurrently with data collection. The first phase of the inductive analysis process was initiated by reading and re-reading the raw data line by line, generating codes, and collating codes into potential themes and sub-themes. The next phase involved the refinement of themes and, finally, defining themes and organizing them into a coherent account. Visual representations help sort the different codes into themes during the different phases and the final abstraction.

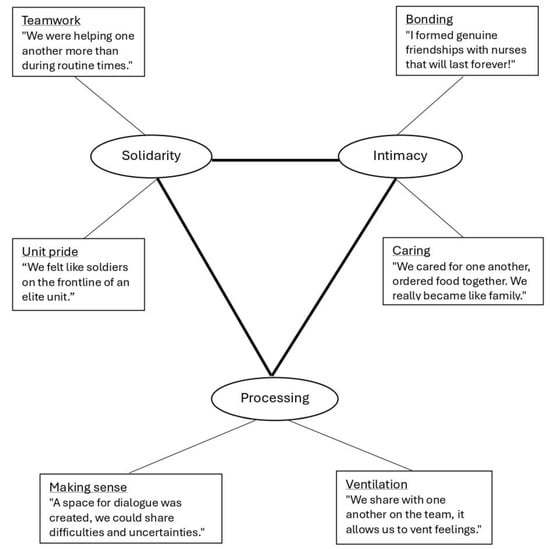

An example of a thematic map is depicted in Figure 1, demonstrating the process of generating codes from data extracts and forming initial themes and final saturated themes. The example refers to colleagues’ support and to the question of how hospital nurses manage the challenges posed by the pandemic in their workplace.

Figure 1.

An example of a thematic map.

Finally, we identified the core category and its relationships with the main categories and sub-categories to form the emerging conceptual framework that relates to our research questions. Figure 1 presents a schematic model of the theoretical framework.

3. Results

A total of 23 hospital nurses from nine tertiary hospitals dispersed throughout Israel participated in the study. Their socio-demographic and professional details are presented in Table 1. A total of 18 females and 5 males were interviewed, aged 24–54 years, and the native languages included Hebrew, Arabic, and Russian. Nursing experience ranged from 1 to 32 years, and four nurses were in managerial positions. The diversity of the participants reflects society and the nursing profession in Israel. Professional experience with COVID-19 patients ranged from 2 to 24 months.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants.

Two main categories emerged in the current study derived from nurses’ experiences during the pandemic: “Nurses’ reactions to the pandemic” and “Management of the pandemic”. The two categories are interrelated, meaning that the way nurses responded to the pandemic played a significant role in how they managed the challenging reality. According to the Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) theory, it is not the event itself that leads to the consequences of posttraumatic stress or growth, but the way people manage the traumatic events [24].

As shown in Figure 2, each category revealed three sub-categories and six themes that will be elaborated on in the next section.

Figure 2.

A schematic model of nurses’ struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. Nurses’ Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The themes that emerged under the reactions category were sorted into three sub-categories: mental, emotional, and physical.

3.1.1. Mental Reactions

The new disrupting reality at the workplace impacted the lives of the nurses and required mental processing to help them make sense of their experiences. Two main themes emerged: (1) perception of threat, risk, and uncertainty; and (2) reframing the meaning of the mission.

Theme 1. Perception of threat, risk, and uncertainty

Nurses continue to recall memories from the time of the pandemic outbreak. They described situations that helped them comprehend the magnitude of the threat of the disease and their risk of being infected while providing direct care to COVID-19 patients. An experienced nurse shared her understanding:

“When I witnessed the extreme deterioration of patients from the moment of admission when they could talk to me until they passed away a few hours later, I said to myself, this is a serious and unexpected disease that can really cause troubles.” P5

An emergency room nurse described how they did not initially realize the high risk of contagion and gradually adjusted their functioning accordingly:

“At first, we didn’t understand exactly what was going on. When I had to transfer lab specimens from the respiratory ER, I would move the divider and hand it over to another staff member who would send it to the lab. Only later did we realize that this was not right, and we constructed walls and double doors where the specimens could be put safely.” P16

The pandemic period was characterized by an absence of knowledge about the disease and treatments; a lack of clinical guidelines; frequently changing rules and regulations; and many organizational changes, as described by an ER male nurse:

“The inability to provide answers to the good questions of patients and families because of our lack of knowledge was difficult. At that point in time, instructions were confusing and changed from moment to moment. When you are faced with such reality at work, then all your clinical senses are undermined.” P14

An intensive care nurse shared her experience dealing with uncertainty:

“We at the bedside were very confused, we were shifted from place to place [...] There were situations I would arrive in the morning, and I wouldn’t know to which department I would be allocated. There was a long period of uncertainty and organizational disorder. The whole period lasted almost a year on and off.” P20

The unexpected, unfamiliar, and uncertain situation posed challenges to the nurses that were perceived as threatening on a personal level and hindered their ability to make informed clinical decisions on a professional level.

Theme 2. Reframing the meaning of the mission

A recurring theme that emerged among the nurse participants was the significance of the mission in terms of a career choice to take care of people under any circumstances and as their professional commitment. A nurse in an internal medicine department described this as a professional challenge and volunteered to be allocated to a COVID-19 department:

“From the beginning, it was clear to me that I would volunteer someday to take care of COVID-19 patients. [...] it intrigued me to understand what this pandemic is. In the medical department, we treat a lot of patients with respiratory problems. Everyone who worked in the COVID-19 department kept telling us that it was something different. [...] When I got there, I realized how different it was.” P19

Some participants used the metaphor of a battle to describe their struggle during the pandemic. A nurse in the COVID-19 department shared her experience of distressing situations, but at the same time expressed her belief in what the profession is about and how she views her mission:

“I dealt with it because it felt like a war; you must continue taking care of people. You see people dying in front of your eyes. It’s hard, we went through very difficult days, but we dealt with it. We must help and try to save lives.” P18

The nurse participants perceived their professional contribution as an important calling. This way of reframing the stressful situation strengthened their ability to be committed and function effectively under circumstances of threat, risk, and uncertainty, such as the current pandemic.

3.1.2. Emotional Reactions

The pandemic aroused mixed negative and positive emotional reactions. Nurses described feelings such as fear, anxiety, helplessness, and emotional exhaustion, along with feelings of courage, heroism, and team camaraderie.

Theme 1. Negative emotions: Fear, anxiety, and helplessness

Fear was one of the strongest and more recurring emotional responses, expressed by the nurses on both a personal and professional level. On a personal level, there was the fear of being infected and contaminating families and friends, as expressed by an ER nurse:

“It was very scary; I was afraid to return home. I feared I would be the cause of infecting my mom and my kids, causing them a serious illness or God forbid death. It was the toughest experience.” P15

In the context of professional performance, the participants expressed anxiety, confusion, helplessness, and exhaustion in the face of the uncertainty of the situation, along with accountability to save lives under harsh conditions. An Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurse who could not stop crying throughout the interview shared her feelings:

“I felt anxiety and fear because of the continuous changes and the uncertainty in the air. Each time, new instructions and everyone says something different. You feel helpless in this situation. There was no certainty and no other choice.... people do not understand what the term “exhaustion” means; what is extreme tiredness when a person wears PPE for seven hours during a shift; what it means to go through one resuscitation after another, while in front of me, several patients are collapsing at the same time and I do not know to whom to turn to first; to whom I will be sufficient to care for and to whom I will not. It tears your soul apart.” P22

Nurses expressed a variety of overwhelming negative emotions that resulted from their personal and professional obligations during the time of crisis.

Theme 2. Positive emotions: Courage, heroism, and team camaraderie

Positive emotions were expressed more intensely during the first wave.

An ICU nurse explicitly stated the following:

“We were kind of heroes on the frontline; I was not afraid to run forward, it was not a problem.” P16

Another ER nurse explained the following:

“In terms of personal feelings, there was a feeling that I am part of something big that is happening, and my contribution here counts.” P18

These positive emotions probably played an important role in balancing the negative emotions and enabling rational cognitive processing under the traumatic circumstances of the pandemic.

3.1.3. Physical Reactions

The emotional distress and the harsh working conditions took a toll on both the nurses’ physical health and their professional ability to function effectively. Among the difficult conditions, nurses mentioned the shortage of nurses, heavy workload, isolated departments, difficulty taking breaks, individual work as opposed to teamwork, prohibition of visitors, long shifts, and the need to provide care with PPE. Two main themes emerged that reflected bodily responses to the traumatic situation: (1) physical symptoms of distress and (2) disruption in the fulfillment of physiological needs.

Theme 1. Physical symptoms of distress

Nurses shared complaints due to exhaustion from the workload and emotional stress. A novice nurse who had just started to work in a COVID-19 department said the following:

“I arrived very tired at the hospital shifts; I did not sleep well at night. [...] I had strong dizziness; there were times I felt I could not stand it anymore.” P12

A shift charge nurse in an ICU shared her difficulties:

“There were very tough days I would collapse with headaches. We did not rest for a moment, there was work all the time and I already had blisters on my feet. I am also a shift charge nurse and so I would have to stay longer shifts and it was tiring and exhausting.” P7

Theme 2. Disruption of physiological needs

The participants described situations when their basic physiological needs were unmet, mostly due to the PPE. Everything had to be calculated in advance. A nurse in the COVID-19 department exemplified this experience:

“We put on protective equipment from head to toe. The N95 masks were tight in a way that hurt us. I remember I had a wound behind my ear and on my face. I was afraid to drink before a shift because there was no option to go to the toilet. You are sweating and wet on the inside and all you want to do is go out for a moment and breathe oxygen.” P10

A certified male nurse from the respiratory ICU also described the difficulties of wearing PPE and how it affected the performance of life-saving actions:

“The hardest thing is the full protection; the unit is crowded, small, and hot. The difficulty breathing and at the same time getting into resuscitation is difficult. I didn’t see what I was doing. In addition, the PPE creates a physical barrier between you and the patient; it does not help the situation.” P14

The complex working conditions during the pandemic caused physical symptoms such as tiredness, difficulty sleeping, dizziness, headaches, body exhaustion, and discomfort associated with PPE. Basic physiological needs were interrupted, which impaired their ability to provide quality care and compassionate interpersonal communication. In summary, the traumatic pandemic produced both negative and positive reactions among frontline nurses that affected their mental, emotional, and physical health and well-being.

3.2. Management of the Traumatic Event

The way nurses managed the dramatic changes in the new reality was identified in the current study as the core category. This category of management of the traumatic event was sorted into three sub-categories: (1) personal resources, (2) social support, and (3) professional support. The themes that emerged in each sub-category are illustrated in Table 2 and described in the next section.

Table 2.

Nurses’ struggle with the pandemic: categories, sub-categories, and themes.

3.2.1. Personal Resources

Two themes emerged from the analysis process of the personal resources sub-category in the current study: nurses’ ability to (1) regulate overwhelming emotions and (2) manage work-life imbalance.

Theme 1. Regulation of overwhelming emotions

The nurse participants shared difficulties in managing negative, overwhelming emotions and described the mechanisms they used. For example, an experienced ICU nurse recalled how she was unable to regulate her emotions during the first wave of the pandemic and just exploded.

“I gained a lot of experiences in my professional life and there were a lot of tough situations [...]. I never shouted or cried in the middle of a shift, but during the pandemic, it did happen to me underneath the mask.” P20

A novice nurse who was allocated to a COVID-19 ICU in a new workplace shared her struggle:

“Most of the time we treat patients who are in very difficult conditions with poor prognosis. Sometimes I feel like I’m becoming an emotionless person and the dead are becoming numbers. Entered-died, entered–died [...] It’s a terrible feeling but that’s what helps [...] I started giving time to myself, reading, and writing about things that upset me. I’d come back from a shift exhausted and I’d get home and write down all the bad stuff and release it. I would leave a shift sometimes crying and a lot of emotions would float, this gave me the option to let go of everything and be alone with myself for a few moments.” P12

During the traumatic reality of the pandemic, especially during the outbreak, nurses used mechanisms such as catharsis or over-sympathy versus emotional detachment. Eventually, they searched for new ways of emotion regulation. The writing was another way to process traumatic experiences. While being physically exhausted and emotionally overwhelmed, nurses took the time and effort to develop self-regulation and self-compensation techniques to achieve personal balance.

Theme 2. Management of work–life balance

During the pandemic, many nurses worked overtime and could not go on leave; some of them reported no vacations for about two years. This situation resulted in a work–life imbalance. Nurses found it complicated to allocate adequate time for themselves, family, friends, and leisure. Despite the difficulties, they found ways to keep thinking positively, demonstrate resilience, and choose strategies to help balance their everyday lives.

A novice nurse demonstrates a positive way of thinking:

“I can’t go on vacation and travel as much as I want. I must take care of my dad and kids. Everything adds worries but life continues, we got vaccinated and if we follow the instructions, then nothing will prevent us from meeting friends and going to the movies soon.” P19

Several nurses reported that they deliberately allocated time for leisure activities during the pandemic, such as sports, physical activity, and new hobbies. When one of the participants, who had just returned to work after labor, was asked how she handled the work–life balance, she described two strategies that worked well for her:

“I go to a cafe at 07:00 o’clock in the morning after my night shift when there is no one outside and it’s quiet, the birds are tweeting, order a cup of coffee and a snack, and experience at least 20 min of quiet, without the noise and the nonstop buzzing of the devices and monitors, without the patients’ shouts, and without the noise of the staff. Sitting in a cafe in the morning, the silence refreshes and restarts me every time. When I come home, then what relaxes me is the cleaning and scrubbing of the house. It gives me a break and relaxation. Unfortunately, my obsession with cleanliness got worse during the COVID period, but this is how I am now. Until I rub away all the frustrations I don’t relax, only after everything is clean and organized can I go to sleep in peace.” P10

While the workplace was intense, demanding, and dramatic, nurses demonstrated resilience by adapting different innovative ways to manage the imbalance between work and their personal lives. Predominantly reported strategies included the need to process their experiences through writing, maintain a positive mindset, engage in leisure activities (e.g., sports, physical activities, and hobbies), engage in distracting activities (e.g., house cleaning, TV watching), and take time out to rearrange the thoughts and emotions aroused at work before restarting everyday life at home.

3.2.2. Social Support

Nurses who managed the traumatic period of the COVID-19 pandemic experienced their social surroundings as a crucial source of support when available. Different themes emerged in the analysis of two circles of social support: (1) the close circle of family and friends and (2) the public.

Theme 1. Family and close friends: concern, support, and pride

All nurse participants emphasized the significant role of family and close friends as the major support resources when managing the challenging circumstances of the pandemic. However, at the same time, they emphasized the difficulty of struggling during the pandemic in the absence of this support because of social distancing. An experienced head nurse described her experience:

“I mostly remember an experience of support and pride. My partner was proud of me and showed it off in front of everyone. [...] My mother was very anxious. She is 83 years old; she took it more to a place of concern. The children and my partner mainly demonstrated support and pride. The children took care of all household chores because I was not available.” P8

Another male head nurse in the ER shared his need for touching and sharing:

“I had not seen my mother for a long time, which was very difficult. On her birthday I arrived at the building where she lives and could only see her from a distance without touching her. My comrades from the military service showed interest in my work at the hospital, they asked me to send them pictures of me with the full protective equipment and they couldn’t believe it. I am a person who loves to share, so the relationship with friends made me feel good.” P17

The support of family and close friends had a crucial impact on nurses’ management of the pandemic. They emphasize the contribution of emotional relief by sharing and processing their experiences; practical help in releasing chores; fulfilling a need for touching; and strengthening their sense of value in the eyes of the people who mean the most to them. In the absence of this significant support, due to social distancing and overload, nurses expressed a sense of loneliness and frustration that impacted their ability to manage challenging times.

Theme 2. Public support: Gratitude and appreciation

The public’s support for the healthcare staff was felt internationally and nationally, as well as within the hospitals, and was felt mostly during the first wave of the pandemic. Nurses described different ways of expressing thankfulness from patients, families, firms, and companies. An experienced nurse in the respiratory ER described the following:

“All kinds of indulgences and sweets made the personnel smile. Ordinary people would donate cakes and cheese, children would create videos, and it felt good to know that they did it with appreciation and wholeheartedly.” P15

A novice nurse in the ER shared her experience, particularly during the first wave:

“In the first wave, because we were at the forefront of the pandemic, we received a lot of gifts and food that people donated. Both patients and companies donated to the hospital staff [...]. We felt that we had strong support from people, society, and the workplace.” P18

Nurses experienced feelings of gratitude and appreciation from patients, families, and the public, which encouraged and strengthened them. However, this support was felt mostly during the first waves and diminished over time, although it did not completely disappear.

3.2.3. Professional Support

Professional support refers to the formal and informal support that nurses experience at the workplace from three resources: the managerial level (i.e., government, hospital, nursing administration, and department managers); therapists (e.g., psychologists, social workers); and nursing colleagues. The analysis process revealed a difference in nurses’ experiences of support from their peer group as opposed to all other support resources. Accordingly, we classified professional support into two sub-categories: (1) managers’ and therapists’ support; and (2) colleagues’ support.

Theme 1. Managers and therapists’ support: Chaos and sporadic support

Nurses in general felt a lack of psychological support during the pandemic from their superiors at all levels. The phrase “we were thrown into deep water by ourselves without help” was repeated. There were only a few outstanding examples of personal interest on the part of a unit nurse manager or a medical manager that were appreciated. An experienced ICU nurse described her viewpoint as follows:

“We are in a kind of chaos and there are changes all the time. I have been in the healthcare system for 20 years, and it seems now like a survival battle. I felt that they [managers] were scared, disorganized, and did not know what to do and how to survive. By and large, they tried to supply food because we worked 12-h shifts and could not go out to buy.” P20

The chaos that characterized the managerial conduct was reflected in how the bedside staff felt. Eventually, when the need for ventilation and psychological aid was identified, hospitals recruited employees in the field of mental health to help their associates, either via support groups or individual counseling. However, nurses, who at that point felt overloaded and exhausted, reported that they did not benefit much from this offer because they did not have the time or energy to attend the meetings. A male head nurse in the ER shared his experience:

“The social worker approached me after observing that I was very nervous. We talked for about an hour, and it was a good release and stress relief conversation. It helped and I would occasionally go to her, but I didn’t have much time for attending the meetings.” P17

When support was sporadic or lacking, nurses expressed disappointment and frustration.

Theme 2. Colleagues’ support: Solidarity, intimacy, and trauma processing

Colleagues’ support was experienced by the nurse participants as the most valuable and empowering source that helped them manage the traumatic period of the pandemic. A nurse manager of a COVID-19 department during all the waves since the outbreak, with 32 years of nursing experience, described the meaning of colleagues’ support from her point of view:

“Something in the experience of fear and not knowing where it was going, that accompanied the staff and the patients, united us. We wanted to defeat the fear by being there for each other. There was a feeling of solidarity and that we were in a strong position and could give something that no one else could. It was a capsule not only in the literal physical sense but also in the emotional sense of unity. A capsule in the sense that it was closed, special, different, distinct, separate, and only we could do it [...] each capsule was a unit camaraderie; there was something intimate about it in the best sense of the word. I haven’t experienced anything like this in the whole time I’ve been on duty as a nurse.” P8

The nurse used the metaphor of a “capsule” to exemplify the meaning of shared destiny, solidarity, and unit pride as significant motivating factors in managing traumatic events. Moreover, they drew strength from the group and felt they were an elite team with unique capabilities to face professional challenges. Another nurse illustrates the intimacy that was developed within the nursing teams, both the original team and the new COVID-19 teams:

“When I joined the COVID-19 department, I didn’t feel alone. I felt I had a listening ear. Even if we did not talk, we would sometimes sit together in silence. When you develop a very high level of intimacy with a person, then you get comfortable. We were a team of diverse backgrounds: Jews, Muslims, Christians-all kinds; an intimacy of understanding was created between us only from a glance.” P20

The intimacy that was developed provided the nurses with opportunities to tell their stories to colleagues who have been in the same situations, as described by a novice nurse in a COVID-19 ICU department:

“What has helped me the most is the staff themselves; we sometimes talked outside of work, after the shift, and between shifts, and a lot of them have become my friends and that helps me a lot.” P12

The nurse participants emphasized the added value of the group in being able to reveal to colleagues and process their experiences with people who understand them the best because they have gone through similar experiences. This way of processing the traumatic event goes beyond ventilation and survival. It enables growth by developing new perspectives and building personal and professional team resilience.

In conclusion, the way nurses managed the COVID-19 traumatic period was mostly through three resources: their personal resources to regulate emotions and find work-life balance; social support from family, friends, and the public that expressed genuine concern, pride, gratitude, and appreciation for their social mission; and professional support from superiors and colleagues. Despite the chaotic situation, nurses felt solidarity and intimacy, especially with their colleagues, which not only helped in survival and ventilation but was also a source for processing the shared distressing experiences that contributed to their well-being and enabled better professional functioning.

4. Discussion

This study explored the experiences of frontline hospital nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in two main areas: (1) nurses’ reactions to unexpected and unprecedented events and (2) their ways of managing the new reality posed by the pandemic.

There is considerable evidence in the literature on the emotional, mental, and physical impact of the pandemic on frontline hospital nurses. However, most findings focused on negative reactions, and more so on negative emotional reactions. Less attention has been given in the literature to exploring nurses’ mental reactions and bodily reactions. In congruence with previous publications, our study also found that nurses perceived the new reality during the pandemic as uncertain, threatening, and risky for themselves and their close relatives [2].

According to the PTG theory, the way people cognitively interpret a traumatic event plays a significant role in their post-traumatic process [25]. In this study, we found that nurse participants reframed their way of thinking about the pandemic by perceiving their professional contribution as an important calling. In other words, nurses’ perception of their meaningful professional mission strengthened their ability to balance negative thoughts and enabled them to function effectively, even in the face of life-threatening and uncertain situations.

Negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, and helplessness that were identified in previous studies support our findings [3,26]. Similarly, positive emotions such as heroism, joy, courage, and positive team spirit that emerged in the current study are also in line with the findings of previous studies [27]. Only a few studies described nurses’ physical symptoms during the pandemic, such as fatigue, muscle pain, backache, insomnia, and discomfort related to the PPE [3,4,18]. Similar findings emerged in this study, with an additional emphasis on the disruption of physiological needs to breathe fresh air, eat and drink, and go to the toilet.

The interrelationship between mental, emotional, and bodily reactions in coping with stress and trauma is well known. Frequently, negative and positive reactions coexist. The abilities of people to manage negative and positive emotions and their physical symptoms affect their thinking and vice versa; thus, cognitive processing can help regulate physical manifestations and emotions [25].

In this study, we explored the way nurses used their personal resources to manage the pandemic and the role social and professional support played in their struggle during this period. On a personal level, a variety of coping strategies are described in the literature that supports our findings: relaxation techniques; self-care; leisure; distracting activities; processing experiences through writing; and searching for new meanings in life [7,19]. The current study emphasizes nurses’ strategies to regulate overwhelming emotions, adopt positive self-evaluation, use self-disclosure, and strive to find work–life balance.

Social support from the public, family, and friends during the pandemic, especially during the outbreak period, was evident and documented as positively strengthening nurses and the nursing profession as valued for their social contribution [18]. These findings were also reinforced by our findings of gratitude and appreciation nurses experienced from the public, whereas, from family and close friends, they felt more concern for their health and well-being, along with instrumental help and emotional support. Evidence about hospital leadership support during the pandemic is controversial in the literature [4,19]. In the current study, nurses described a lack of planned and structured support from senior management. Evidence was found of the positive effects of organizational compensation strategies on nurses’ mental health and burnout [28,29].

However, the most meaningful support that nurses received was from their colleagues. Nurse participants in the current study acknowledged the strong solidarity that was rapidly established among the original and new teams. Feelings of intimacy and team camaraderie enabled the disclosure and processing of the shared traumatic experiences. This was the most powerful resource that helped nurses manage the major traumatic pandemic. Nurses’ well-being is key to the quality of patient care. Team support and personal management strategies were crucial for coping

The nursing literature is replete with research studies since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing an abundance of rich results that can be sometimes confusing and difficult to make sense of or draw conclusions from. The important insight is that post-traumatic growth emerged out of affective–cognitive processing, self-disclosure, social support, questioning basic assumptions, and developing new meanings [24,25]. These understandings provide ground for future directions of interventions.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Work

A purposeful sampling strategy was applied in this study to interview nurses from nine tertiary hospitals in Israel from a variety of clinical fields with a diversity of characteristics (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, roles, and professional experience). However, the research was conducted in only one country; therefore, transferability to other countries should be examined. While face-to-face video interviews were the optimal option according to Ministry of Health safety guidelines during the pandemic, live interviews may have provided better opportunities for interviewer-interviewee interaction. Trustworthiness criteria were applied with the acknowledgment that researchers’ perspectives as nurses and citizens during a pandemic may have impacted interpretations and the results of the research. The transferability of the findings should be judged based on the transparent and rich descriptions provided in this study.

4.2. Recommendations for Future Research

More evidence-based research is recommended to address the under-researched phenomenon of secondary traumatization among frontline nurses. Intervention studies are needed to explore ways to help nurses manage challenging situations in clinical work.

5. Conclusions

Nurses are routinely exposed directly to traumatic events or secondary traumatization through their patients in routine times and more so in times of crisis. Most nursing studies during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the current study, provided evidence that nurses’ needs for support have not been sufficiently met by leadership. However, local informal peer support initiatives have proven effective in struggling with devastating events. During our study, we discovered that the interviews themselves were, for many of the participants, an opportunity to share and reflect on their experiences. By telling their narratives, they processed the events, named their emotions, and gained new understandings of their experiences. Several nurses became aware of the beneficial changes they had experienced during the pandemic and were appreciative of the process.

The study findings helped to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of nurses’ mental, emotional, and physical experiences during the pandemic, the ways they managed the challenges, and what were their needs and expectations that were not met. This added knowledge can be used to provide directions for future policy-making and clinical practice.

Relevance to Education, Practice, and Policy

Affective–cognitive processing of direct and secondary traumatic events should be structured and integrated into the workplace to preserve frontline nurses’ mental, emotional, and physical health. Debriefing training should start in nursing education and be utilized in all areas of nursing practice. To achieve this purpose, it is recommended to allocate resources for individualized or team debriefing interventions. Trained nurses, or in cooperation with mental health professionals within the health care system, can serve as facilitators. This is critical not only in times of emergencies but also in routine times. Nurse leaders are encouraged to promote interventions for nurses that will contribute to their well-being and eventually impact the quality of care they provide.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid4070068/s1, File S1: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ): a 32-item checklist [30].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, H.A. and L.I.; acquisition of data, H.A. and L.I.; analysis and interpretation of data, H.A., L.I., S.B. and S.S.; writing-original draft, H.A.; writing-review and editing, H.A., L.I., S.B. and S.S.; visualization and supervision, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of YVC (protocol code No. 2021-69, approval date: 27 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the primary investigator (H.A.), upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the nurses who voluntarily shared their experiences to participate in the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boone, L.D.; Rodgers, M.M.; Baur, A.; Vitek, E.; Epstein, C. An integrative review of factors and interventions affecting the well-being and safety of nurses during a global pandemic. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D. Reflections on nursing research focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, e84–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, E.; Widestrom, M.; Gould, J.; Fang, R.; Davis, K.G.; Gillespie, G.L. Examining the impact of stressors during COVID-19 on emergency department healthcare workers: An international perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, E.T.; Narva, A.M.; Holland, S.; Smith, J.G.; Cramer, E.; Rosenbaum, K.E.F.; French, R.; Clark, R.R.S.; Rogowski, J.A. Hospital nurses’ moral distress and mental health during COVID-19. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.T.; Trask, C.M.; Rafiq, M.; MacKay, L.J.; Letourneau, N.; Ng, C.F.; Keown-Gerrard, J.; Gilbert, T.; Ross, K.M. Experiences and Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Thematic Analysis. COVID 2024, 4, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, İ.; Taylan, S. Experiences of nurses providing care for patients with COVID-19 in acute care settings in the early stages of the pandemic: A thematic meta-synthesis study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 29, e13143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, Y.; Güdül Öz, H.; Akgün, M.; Boz, İ.; Yangın, H. Qualitative exploration of nurses’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic using the reconceptualized uncertainty in illness theory: An interpretive descriptive study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Derezza-Greeven, C.; Herzog, W.; Nikendei, C. Secondary traumatization in first responders: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1562840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, G.; Feng, R.; Wang, W.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. Anxiety, depression and insomnia: A cross-sectional study of frontline staff fighting against COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş, Y.; Karacan, Y.; Güney, R.; Kurt, B. Experiences of nurses working with COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 31, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vivar, C.; Rodríguez-Matesanz, I.; San Martín-Rodríguez, L.; Soto-Ruiz, N.; Ferraz-Torres, M.; Escalada-Hernández, P. Analysis of mental health effects among nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs 2022, 30, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EI Hussein, M.T.; Mushaluk, C. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Nursing Students and New Graduate Nurses: A Scoping Review. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2024, 38, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, C.Y.; Lee, B. Systematic Review of Mind–Body Modalities to Manage the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.D.; Urban, R.W.; Foglia, D.C.; Henson, J.S.; George, V.; McCaslin, T. Well-being in acute care nurse managers: A risk analysis of physical and mental health factors. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohisha, I.K.; Jibin, M. Stressors and coping strategies among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmari, M.; Nayeri, N.D.; Palese, A.; Manookian, A. Nurses’ safety-related organizational challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliano, L.; Papa, C.; Di Maio, G.; Bonavigo, T. Staff opinions on the most positive and negative changes in mental health services during the 2 years of the pandemic emergency in Italy. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2024, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wei, L.; Shi, S.; Jiao, D.; Song, R.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; You, Y.; et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020. 48, 592–598. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Y.; Baghaei, R.; Hosseingholipour, K.; Mollazadeh, F. Challenges experienced by ICU nurses throughout the provision of care for COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, C.; James, S.; Williams, A.; Calma, K.; Mcinnes, S.; Mursa, R.; Stephen, C.; Halcomb, E. The psychological well-being of primary healthcare nurses during COVID-19: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3820–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatro, M.; Prasad, M.M. The experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 crisis in India and the role of the state: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maben, J.; Bridges, J. Covid-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Murphy, D.; Regel, S. An affective–cognitive processing model of post-traumatic growth. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, K.J.; Forster, A.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Chiu, Y.C. Voices from the COVID-19 frontline: Nurses’ trauma and coping. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3853–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konwar, G.; Kakati, S.; Sarma, N. Experiences of nursing professionals involved in the care of COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2022, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M.; Pien, L.C.; Kao, C.C.; Kubo, T.; Cheng, W.J. Effects of work conditions and organizational strategies on nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbuAlRub, R.F. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).