Abstract

At the beginning of July 2022, when public health restrictions were lifted, we deployed a country-wide e-survey about how older people were managing now after COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety. Our responder sample was stratified by age, sex, and education to approximate the Canadian population. E-survey responders were asked to share open-text messages about what contemporaries could do to live less socially isolated lives at this tenuous turning point following the pandemic as the COVID-19 virus still lingered. Contracting COVID-19 enhanced older Canadians’ risk for being hospitalized and/or mortality risk. Messages were shared by 1189 of our 1327 e-survey responders. Content analysis revealed the following four calls to action: (1) cultivating community; (2) making room for what is good; (3) not letting your guard down; and (4) voicing out challenges. Responders with no chronic illnesses were more likely to endorse making room for what is good. Those with no diploma, degree, or certificate least frequently instructed others to not let their guard down. While COVID-19 is no longer a major public health risk, a worrisome proportion of older people across the globe are still living socially isolated. We encourage health and social care practitioners and older people to share messages identified in this study with more isolated persons.

1. Introduction

In any infectious disease outbreak, the public remains the most important asset, because each person must take care of themselves and those who matter to them [1]. Public health messages that are evidence-based are practical ways to help people at risk [2], such as through dispelling myths about self-protection practices [3] and advising self-safety and mental health maintenance [4]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the public was forewarned that people aged 60 and older were at a higher risk of needing intensive care and also more at risk of dying [5].

Actual or potential threats of physical harm and separation from familiar faces and places are frightening consequences of large-scale traumatic events [6], such as the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. In a national survey involving some 23,000 Canadians aged 50 and older, being away from family was their biggest mental stressor during the pandemic [8]. Mundane practices like essential shopping became frightening [9]. Continuing to hear negative news about COVID-19 was also frightening [10]. Older Canadians were subsequently found to be the most likely age group to adhere to public health measures [11,12] and to harbor more fears than younger adults (75% versus 63% among younger adults, respectively) over lingering health threats after the COVID-19 pandemic ended [9].

Age is an established risk factor for being socially isolated [13,14], and some argue more were socially isolated because of COVID-19-related public health measures [15]. Socially isolated people typically lack regular company and conversation due to larger geographic distances, health impediments, and tenuous or sparse ties with friends and family [16,17]. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada-wide surveys revealed 40% of older persons [18] and 57% of late-midlife and older adults [11] self-identified as socially isolated. Later, well into the first year, about one in three older persons across Canada were considered socially isolated [19]. Similar proportions were observed in six other countries [20]. While the COVID-19 virus is no longer a global health threat [21], about one in four older people across the globe are still living more isolated lives than they did before the pandemic [22].

Guiding Conceptual Framework

Public health messages about the risk of health-related harms of COVID-19 cast older people in a primarily vulnerable light [23,24]. However, as Hobfoll et al. [6] long argued, pernicious problems stemming from large-scale traumatic events are more surmountable when the very people whose lives are or could be directly impacted have some means to tackle them. In keeping with our guiding Stakeholder Engagement framework from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research [25], people who either are socially isolated or at risk of being socially isolated and not by choice could find solace in knowing that they are not alone in their struggles. In widely broadcast national surveys, older Canadians informed contemporaries that a lack of companionship can be detrimental to your overall health and well-being [19]. Disrupted everyday social activities could make a person prone to poorer mental health [9], such as from feeling left out and longing for a companion [12].

Good health promotion information, about mental wellness or the social relationships that help people stay this way, enhances risk-related awareness and capacity for remedial action [2]. People living in harm’s way of an infectious illness are also keenly aware of the complex realities that they must juggle to stay healthy [26]. Prior to COVID-19, social isolation in later life was linked with heart disease and stroke, depression, anxiety, and even premature death [13,14,27]. With the advent of COVID-19, Sepúlveda-Loyola and colleagues observed similar secondary mental health harms across five countries, including Canada [28]. Other large-scale studies link smaller social networks to lower mental well-being [29], social participation [30], and living alone [31] with depressive symptoms.

It is also important to note that older people differently experienced the psychosocial impacts of COVID-19 [23]. For some, small social circles seem to have lessened emotional negativity [32] and depressive symptoms [33] or were a source of contentment [34]. Lived experiences enhance people’s capacity to be purveyors of solutions from a wide variety of perspectives [25]. Peers with lived experiences play an important role in instigating and augmenting others’ mental wellness recovery work [35,36]. A Canadian Coalition of Seniors Mental Health survey also revealed that one in five responders were ill at ease talking with health care practitioners about being socially isolated [37]. Older people should be considered experts about their social positioning in life [22], including their preferred wants and needs [17].

The aim of this research was to provide a gathering space for older Canadians to share solutions on how to live a less isolated life, based on their own experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. They shared insights and ideas about what a quality social life can look like immediately following the COVID-19 pandemic and thus while navigating open spaces after public health measures were lifted.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

The overarching project where this research is placed had two aims, the first being to learn from older people in any of Canada’s 10 provinces about coping behaviors statistically significantly associated with mitigating their pandemic-related anxiety [38]. This study fulfills a different aim, namely to gather and share later-life Canadians’ recommended strategies to mitigate pandemic-related social isolation.

2.2. Sample

The overarching parent study where this research is embedded used a stratified sampling approach [36]. Participants were selected considering Statistics Canada’s (2017) census distributions for age, gender identification, and education [39]. In other large-scale COVID-19 studies of older Canadians, age [9], education [8,19], and identifying as a non-binary person [40,41] have been significant determinants of mental health. Other studies have linked age and education with social isolation before [13,14] and during [9,19] COVID-19.

All study variables in the overarching project were defined using the Census of Population dictionary [42]. For example, gender pertains to a person’s personal and social identity as a man, woman, or non-binary person, whereas sex at birth is based on a person’s reproductive system and physical appearance. Census proportions for 2021, which would have included gender identity, were not yet available to us.

2.3. Data Collection

The first week of July 2022, after social distancing requirements were lifted across Canada, older people were transitioning into open spaces, although COVID-19 lingered. At this time, the principal investigator and team co-designed a 36-item e-survey for the overarching project with Qualtrics, a survey research company with expertise in nation-wide health and social surveys [38]. Qualtrics sent a study advertisement about our e-survey to its survey panel members across all 10 Canadian provinces. Potential responders were first taken to an information letter identifying our research aim and their role, with assurances of complete anonymity and contact information for a national support resource. This letter is presented in the Supplementary Materials Exhibit S1.

Qualtrics did not disclose the names of or contact information (and therefore the number of) for any potential responders receiving the study advertisement or consenting to and completing our e-survey. All study investigators were ethically bound to remain impartial (Pro0118512) or at arm’s length during data collection. Up to three reminders were sent to non-responders, and USD 4 in Canadian Consumer Rewards were given to responders, regardless of how many e-survey questions they answered. To protect confidentiality and further enhance data quality, each responder was assigned a unique identifier number and a single-use link to prevent multiple completions. The Qualtrics platform also supports bot detection.

Six weeks after our e-survey launched, survey responses ceased. At this time, Qualtrics sent us a completely anonymized dataset collected from 1327 responders. Among all such responders, 1189 (89.6%) offered social isolation remedy messages.

Our e-survey contained an open-text response box permitting social isolation remedy messages of responders’ own choosing, as opposed to clicking on predetermined responses. They could share as much or as little as they wished about the following: “With COVID-19 public health measures lifting, based on your own experience, what would you suggest other older Canadians do to reduce social isolation?”. The focus of this paper is on the e-survey responder responses to this question.

2.4. Data Analysis

Our analysis was an inductive content analysis [43,44] performed using NVIVO version 14.23.2 [45]. All 1189 social isolation remedy messages were transcribed verbatim and read on multiple occasions. Open word-by-word textual code permitted us to identify distinct meanings within messages. In keeping with our guiding framework [25], we paid equal attention to words conveying a variety of wants and needs for company and companionship. Open codes were then grouped based on similarity and dissimilarity, abstracted as subcategories, and distinctly named. We expected to find older people’s social wants and needs are not homogenous wants and needs [17,23].

More specifically, two qualitative researchers immersed themselves in the data on two separate occasions to independently design coding trees. Each analyst grouped subcodes under higher-order codes or categories to lend meaning to abstracted subordinates. Consensus was then established in a series of online meetings with the principal investigator as to all orders of categories and a universal coding tree and codebook for further analysis.

In addition, we used natural outfalls in observed frequencies between and within higher-order codes or categories, as these permitted a structure with a nominal hierarchy of subcodes or subcategories. We compared higher-order category frequencies across known sampling strata (age, sex, and education) to further validate our observations [35]. We did so by using Chi-square statistics, with Phi as a measure of effect size [46] using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.1.0 [47]. Moreover, with social isolation having been found to be more prevalent among older people in poorer health, and also among those with multiple chronic illnesses during COVID-19 [30,48], we undertook exploratory self-rated health comparisons as well.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of 1189 older Canadians responded to our open-ended e-survey question about remediating social isolation. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 1189).

3.2. Identified Categories of Content

Content analysis of social isolation remedy messages yielded four principal remedies, under which seven actionable categories and ten subcategories of specific ways of behaving and thinking fell (Figure 1). These four remedies were as follows: (1) cultivating community; (2) making room for what is good; (3) not letting your guard down; and (4) voicing out challenges. Because messages were completely anonymous, we outline the content of these overarching and subordinate categories using pseudonyms.

Figure 1.

Coding tree for social isolation remedy messages.

3.2.1. Content Category 1: Cultivating Community

The most substantial proportion of messengers spoke of rebuilding or rekindling a sense of community using hybrid forms of communication with loved ones and by expanding community networks. Another strategy, getting in gear, outside and routinely in open spaces, was encouraged more often than solitary mental occupations.

A good proportion of messengers recommended investing time and energy mainly into rekindling connections with people in your immediate social network. Samuel elaborated: “I use Facebook to keep in touch with family and friends” [Samuel, non-binary messenger, 70–74 years of age]. Joanne [female messenger, 60–64 years old] remarked, “try to have phone check-ins daily with family and friends”. John [non-binary messenger, 60–64 years old] suggested that others “learn and use modern day technology such as phone calls, Zoom or Facetime to connect with people”. As Aiden [male messenger, 60–64 years old] averred, “Try to keep in touch with family and friends even if only through the phone or social media. But in person as much as possible or reasonable given your circumstances”. Friendships were of equal priority.

Jonathan suggested, “stay in touch with family and friends whether in person or online” [male messenger, 70–74 years old]. Karlina and Luke advised, “consider others, check in with them by telephone, have porch visits” [Karlina, female messenger, 75–79 years old], and “I golf with my son and close friends that are fully vaccinated” [Luke, male messenger, 80–84 years old].

Others encouraged non-human companionship. Aster’s [non-binary messenger, 60–64 years old] requesting “get[ting] a dog, cat or bird” rang true for others: “I kept in contact with friends by phone and had long chats. I had the company of two cats, and that helped” [Beeja, female messenger, 80–84 years old], and “I myself go for several walks a day with my dog” [Gilbert, male messenger, 70–74 years old].

Some messengers were far less inclined to tell others to extend their reach by making new community connections through volunteer work, albeit seemingly informally. As two advice givers said, “contact others even if you feel Ok. They may need your help” [Somani, female messenger, 85 years old and over] and “contact others even if you do not need them, but the others may need your help” [Susana, female messenger, 85 years old and over]. Sarah and Tom remarked, “volunteer your time to help others” [Sarah, female messenger, 70–74 years old] and “get involved with volunteer work” [Tom, non-binary messenger, 60–65 years of age]. Very few messengers (n = 34; 2.71%) encouraged extending your reach to simply socialize or to “get out to the coffee shops and meet other older individuals” [Charlie, male messenger, 65–69 years old] and “join a social group with similar interests” [Allan, male messenger, 60–64 years old].

Getting in gear by getting out and about into open spaces like gardens and parks, or enclosed gyms, clubs, and community centers routinely was key to living a less isolated life. Luke [male messenger, 80–84 years old] insisted: “Be active, walk, run, ride a bike, socialize and do not stay indoors”. Robert [male messenger, 65–69 years old] told others: “Go out. Don’t buy groceries online”. For Lartey [non-binary messenger, 65–69 years old], getting out meant “join(ing) local groups at the local community centers”. Angie [female messenger, 70–74 years old] shared such sentiments: “Get out of the house and look after (your) garden, watering and pruning plants and chatting with neighbors who are outside either gardening too or just enjoying the sunshine on their picnic chairs”. Being idle would simply not do.

Getting in gear indoors pertained to solitary mental occupations. For example, Oliver [male messenger, 65–69 years old] recommended, “every morning … do some yoga poses”. Others instructed contemporaries to “have positive experiences ready (a great movie, a great book, a great TV show)” [Benjamin, male messenger, 70–74 years old] and to “take up a hobby or do baking or cooking” [Lida, female messenger, 60–64 years old]. Oliver and Wilson suggested, “keep busy, active, and continual mental stimulus, card games online, reading, crosswords, sudoku” [Oliver, male messenger, 85 years old and above] and “use the internet to read, keep in touch and entertain oneself” [Wilson, male messenger, 60–64 years old]. These savvy non-COVID escapes were seldom recommended, however.

3.2.2. Content Category 2: Making Room for What Is Good

A good number of the messages pertained to being one’s own steward. Such stewardship entailed well-intentioned actions directed at the self and adopting a mindset wherein transitioning into open spaces without mandated public health measures is another good thing to do.

Messengers primarily spoke about finding time and investing energy into fulfilling your own wants and needs, or as Carmel asserted, “Take care of yourself” [female messenger, 70–74 years old]. Self-care spaces were for mentally and emotionally recharging one’s own batteries, with or without other people. One could “get together with your neighbors even if it is six feet apart; conversation and laughter can usually make life better” [Shaski, female messenger, 60–64 years old]. James recanted, “go for a walk to the park so you will see other people, read a book to take your mind somewhere else…” [male messenger, 60–64 years old]. For Tammy [female messenger, 65–69 years old], this meant: “Make a plan to do different things in a day, time to read, time to exercise, time to have meals, time to play online games, time to shop and time to watch some TV and have a good night’s sleep”. Another advised, “be very kind to yourself and do not keep yourself cooped up inside if you can help it. Go for a walk, go for a drive; breathe in the fresh air, listen to beautiful music, watch programs that will make you laugh; see friends that listen and can joke around with you and laugh with you. Eat good food that you like the taste of and drink lots of water” [Margrita, unknown gender, 60–64 years old].

Messengers further emphasized being mindful of the social spaces that you gravitate to. As Ali puts it, “very carefully select where you go, and whom you see. Also, be careful about whom you allow in your home” [male messenger, 65–69 years old]. Others used words such as “be extra careful”, “be cautious”, and “be safe”. Like Julia, they encouraged inhabiting large, open spaces to avoid crowds: “Get outdoors, walking, biking, beach combing” [Julia, female messenger, 60–64 years old]. Others recommended: “Get out in nature” [Barbara, female messengers, 60–64 years old] and “Go outside and enjoy creation” [Bella, female messenger, 65–69 years old]. Oliver [male messenger, 60–64 years old] further averred: “Just be careful and mindful of what is around you”.

For people like Joilana, it was important to create learning spaces to “pursue new interests” [female messenger, 80–84 years old], such as through technology and hobbies. Salim also remarked, “learn and use modern-day technology such as phone calls, Zoom or Facetime” [male messenger, 80–84 years old]. Cassie and Ozeh said, “take a free online learning course” [Cassie, female messenger, 65–69 years old] or “(learn) something new from YouTube” [Ozeh, male messenger, 65–69 years old]. Ceci encouraged others to “take up or revisit a hobby, play or learn to play a musical instrument” [female messenger, 70–74 years old]. New learning spaces were least recommended but were still a means to be good to yourself.

Good thinking, albeit about cultivating what is right in front of you or seeking out new community connections with COVID-19 still lingering, meant living with acceptance. Some said, “[it is] most important is to live your life” [Naina, female messenger, 65–69 years old], “accept things as they are” [Takra, 60–64 years old], and “live normally” [Nichole, non-binary messenger, 75–79 years old]. Likewise, Henry told others, “there is no choice but to accept and enjoy” [male messenger, 65–69 years old]. Alexander [male messenger, 70–74 years old] did not mince his words when telling others to soldier on: “Do not live in fear or in a bubble”.

Fewer messengers spoke of finding hope in what the COVID-19 pandemic brings to your doorstep. A messenger named Anderson [Female, 60–64 years old] echoed such sentiments: “Keep hope in your heart. Sounds like many of us are feeling the same way”. Living this way meant not ruminating over what lies ahead or your present circumstances, for that matter. As Danial [male messenger, 85 years old and older] puts it, “Enjoy each day”. Henry [male messenger, 60–64 years old] conveyed, “talk to someone close to you, and do not assume your condition is worse than anyone else’s”. Others offered reassurances: “Do not worry” [James, male messenger, 70–74 years old], and “Most of all, this (COVID) will end, and life will slowly return to normal” [Deanna, female messenger, 65–69 years old].

Very few messengers mentioned spiritual practices. These were broad practices that included connecting with others. Martin remarked, “Have a good relationship with friends, family and God” [male messenger, 70–74 years old]. Sherry urged others, “if you are religious pray or try to go to church” [female messenger, 80–84 years old]. Connecting with a higher power, scripture, and nature were other good headspaces to be in, away from COVID. Others craved more solitary pursuits: “Learn to be happy on your own” [Todd, male messenger, 65–69 years old] and “It is hard to cope but try meditation and relaxation!” [Deanna, female messenger, 75–79 years old]. Likewise, Hillary [female messenger, 75–79 years old] said, “read good books, pray, and read the Bible, … listen to music you love, exercise and take walks, enjoy nature and keep yourself occupied”.

3.2.3. Content Category 3: Not Letting Your Guard Down

Taking precautionary measures while transitioning into open spaces was also on messengers’ minds. They spoke of taking action on your own part and of keeping on top of public health measures.

Charlie’s [male messenger, 60–64 years old] suggestion about “go(ing) back to doing the things they did before COVID-19 but with a little more protection” was a common sentiment. Alia suggested, “start interacting with people at the same time being vigilant and cautious of your surroundings” [female messenger, 70–74 years old]. For others, this also meant “disinfect(ing) your hands often” [Josephen, female messenger, 70–74 years old] and “minimiz(ing) risks by keeping maximum distance and wear a mask in crowded areas” [Natalie, female messenger, 60–64 years old]. Navis [non-binary messenger, 70–74 years old] suggested, “if you are stuck, go out wear your mask stay away from large crowds just stay safe”. Keema [male messenger, 70–74 years old] implored: “Make sure you’re fully vaccinated and then socialize—COVID is going to be here for a long time”. Hani [female messenger, 75–79 years old] wanted others to “take …vitamin D, vitamin C, and magnesium”. There were also 49 messengers concurring with Erica’s [female messenger, 70–74 years old] sentiments that “they (older Canadians) should stay at home to protect themselves”. Much like cultivating community, decisive and purposeful action was required.

Before our e-survey launched, messengers had been living through lockdowns and social distancing for a two-year period. Expert measures were certainly mentioned, but far less frequently than taking things into one’s own equally prudent hands. Aiden [male messenger, 75–79 years old] told others, “Listen to what Health Canada says”. Mike [male messenger, 65–69 years old] spoke of “maintaining safety protocol[s]” while going outside in public. Bala and Doug were hardly remiss in reminding others: “Make sure you have all your shots and continue to wear masks whenever you feel it necessary” [Bala, male messenger, 75–79 years old] and “Continue to isolate. The danger is NOT past!” [Doug, male messenger, 65–69 years old].

3.2.4. Content Category 4: Voicing out Challenges

Some messengers shared personal hardships pertaining to broader social determinants of health, ones that perhaps made transitioning into open social spaces a difficult thing to do.

Ormara [female messenger, 70–74 years old] disclosed: “I have decreased my social interaction because I am not allowed to drive due to health issues, and more”. Priscilla [female messenger, 60–64 years old] was missing a central figure in her life: “My husband passed away in the midst of the pandemic; my time and thoughts were always elsewhere”. Ozeh [male messenger, 65–69 years old] was mindful of media headlines: “Avoid daily media news as much as possible given its focus on negative and divisive reporting and catch up on the news on the weekends”. Zain soberly spoke about money: “Life has become too expensive to go out and doing things like before. Not only is it still too dangerous to go out because COVID inflation is preventing that as well. Life for most older people will never be the same…” [male messenger, 75–79 years old]. Others, perhaps in hindsight, urged: “Do not be afraid to ask for help” [Kari, female messenger, 75–79 years old] and “Let your doctor know if you are having problems in coping” [Dalia, female messenger, 65–69 years old].

3.3. Between-Group Comparisons

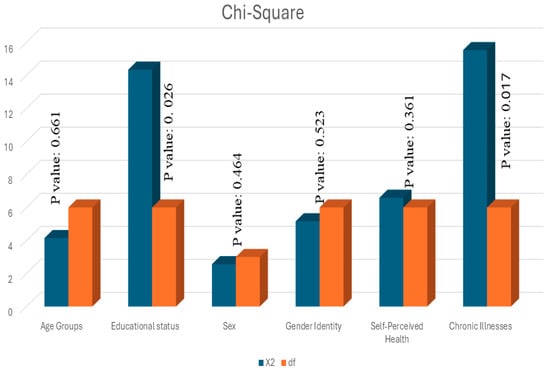

Messengers did not differently endorse all four primary remedies by age (X2 = 4.115, df = 6, p = 0.661; w = 0.064[0.051–0.146]), sex (X2 = 2.562, df = 3, p = 0.464; w = 0.051[0.024–0.123]), and perceived health (X2 = 6.587, df = 6, p = 0.361; w = 0.081[0.055–0.166]). Gender identity (X2 = 5.162, df = 6, p = 0.523; w = 0.072[0.060–0.149]) also seemed to have little bearing on their sentiments. Endorsement patterns were moderately associated with education (X2 = 14.338, df = 6, p = 0.026; w = 0.12[0.089–0.196]) and number of chronic illnesses (X2 = 15.528, df = 6, p = 0.017; w = 0.124[0.091–0.196]) [46]. Not letting your guard down was least frequently mentioned by messengers without a degree, certificate, or diploma (n = 27, 19.3%) versus high school (n = 53, 37.9%) and post-secondary (n = 60, 42.9%) graduates. Messengers with no chronic illnesses (n = 128, 44.8%) most frequently instructed others to expect what is good in life versus those with one [n = 59, 20.6%] or two or more [n = 99, 34.6%] chronic illnesses. These patterns of endorsement are illustrated below in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Remedy message endorsing based on responder characteristics.

Figure 3.

Between-group comparisons of remedy message endorsement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Interpretation

The COVID-19 pandemic has been called “the worst combined health and socioeconomic crisis in living memory and a catastrophe at every level” [50]. Following two years of living with this pandemic, older Canadians were transitioning into open social spaces, and under the auspices of having lived lives most at risk for serious health harms [5].

In the first year of COVID-19, about 8 out of 10 older Canadians taking part in a Government of Canada survey about social distancing prioritized communicating with family and friends [51]. Family and friends have traditionally been older people’s mental wellness confidants [9] and outlets for emotional release [32,34,52]. The loss of face-to-face contact with family and friends made some older people more ‘isolation-aware’ [53]. Technology became an everyday lifeline to family, friends, and peer support [53,54].

In our study, messengers most frequently encouraged encounters with family and friends, albeit a mix of virtual and in-person encounters, with pets perhaps helping to fill physical distances in-between. The best social spaces were hybrid spaces, primarily for investing time and energy into staying connected and checking in with familiar others.

Messages were shared about investing time and energy into building new community connections, largely through informal volunteering. Before COVID-19, Canadians aged 59 and older typically spent about 180 h each year formally volunteering and then far more informally volunteering [55]. Pandemic lockdowns and public health measures understandably curbed such philanthropy. Very early in the pandemic, survey study findings revealed that 4 out of 10 inactive volunteers were age 65 and older [56]. This age group was experiencing dissatisfying declines in community belongingness [57], and particularly if living alone and feeling isolated [19]. Older Canadians felt accepted within their local communities [11] but were dismayed over their lack of opportunities to run errands for others in need, even if they lived in their own neighborhood [58].

For older people without good or readily accessible family or friendship ties, volunteer work can be a source of new and meaningful age-mixed social connections [56,59]. With technology gaining social momentum in older people’s lives, e-volunteering [55,60] could be an equally palatable means of bringing them together to reduce their own isolation and for those seeking company and companionship. Volunteerism can create social momentum, like a rolling snowball, binding people more tightly to the communities where this work takes place and perhaps extending their reach to unexpected others [16]. Older Canadians’ post-COVID-19 social philanthropy work thus bodes further empirical attention.

Routine activities were important to the messengers in this study. They favored routinely getting out into open spaces like gardens and parks, or enclosed gyms, clubs, and community centers so they could be around other people at a safe distance. With lockdowns and social distancing, everyday routines abruptly changed. For some older people, this led to family conflicts [11,48] and foregone friendships [60,61]. Perhaps this is why the physical presence of unknown others on routine walks [53] and making a habit out of being active around other people [53,62] were thought to be mentally beneficial.

Cultivating community through a mix of social and solitary strategies, while being mindful of the social spaces you occupy, could signify a call-to-action to put some of your lockdown-related learnings to work. Quiet gardening [63] and hobby work [59] have helped other older Canadians escape pandemic-related stresses and strains.

In a similar vein, messengers advised contemporaries to make time for themselves to mentally and emotionally recharge through everyday outlets like driving, eating, reading, and simply breathing. Early in the pandemic, for some older people, taking “me-time” dampened their emotional negativity [52] and fear [64] towards COVID-19. Learning new things and putting new ideas into practice [65] were also important to them. Our messengers were far more inclined to focus first on recharging before finding new learning spaces to mitigate social isolation. Older people who recharge might be better able to help and connect with others [55], such as through informal volunteering.

For the messengers in this study, living with hope was an important way to live while transitioning into open social spaces. During social lockdowns, older Canadians spoke of not losing hope for the future [59]. Afterwards, when social distancing lifted, hope largely pertained to living in the present and not ruminating about what lies ahead. Messengers expressed these sentiments by urging others to accept what was going on around them and return to living some kind of social life. Just as Luxembourgers kept occupied during lockdowns by mapping out a hoped-for social life [66], older Canadians were advised to keep occupied during transitioning by accepting and finding hope in what life brings to your doorstep.

Spiritual practices are health-enhancing connectedness practices, albeit through a higher power, caring for others, or taking in natural landscapes [65]. As such, spiritual practices can also be social practices. Our messengers scarcely drew attention to spirituality. Nevertheless, when public health measures were in place, about one in three older Canadians engaged in some form of spiritual practice [42]. Spiritual practices can offer hope and bring comfort [50], perhaps by dissuading our negative emotions [67] and a higher power strengthening our resolve [68]. However, messengers spoke more frequently about hardships or barriers to more fully socially transitioning, including tight budgets, inclement health, negative news headlines, and the loss of someone significant. People can find solace in knowing they are not alone in their struggles [25]. Sharing such hardships could help others weather and/or see the upside about their own lives [69,70]. Shared hardships can also leave people on an uneven spiritual keel, perhaps questioning and even altering spiritual practices that should keep the self and others in safer hands [71,72].

When our e-survey was launched, older Canadians had experienced seven waves of COVID-19 [73]. Very nearly one-quarter of messengers overtly called for some degree of guardedness around personal protective equipment, such as through masking and handwashing and getting vaccines. Others among them strongly suggested not going out at all. Messengers subsequently generously instructing contemporaries to not be shy about reaching out for help reflects an embodied commitment to their own social recovery and to helping others gain momentum.

4.2. Public Health Implications

The results of this national study have implications for varied practitioners and program developers working with older adult populations. Public health messages about the spread and impact of COVID-19 have largely cast older people in a vulnerable light [23,24], seemingly without lessening others’ age-negativity [74,75]. The Commission of Social Connections has called for communities to knock heads to identify practical solutions to post-COVID-19 social isolation among older populations [76]. Our findings draw attention to older Canadians’ social isolation remedy messages based on their own experiences at a key time in the COVID-19 pandemic. These remedy messages are perhaps even timelier now as we continue to live with periodic COVID-19 resurgences.

Good community initiatives bring everyday people together for a specific purpose, including bettering others’ lot in life [25], such as making research findings accessible for everyday citizens and community advocacy groups [77]. Another option, a digital innovation, is the freely downloadable “Cooking up calm” cookbook that was developed in collaboration with a research chef and communications specialist [78]. This public health promotion resource discusses the many benefits of cooking beyond nutrition, including strategies for easing heightened anxiety among older people. There are a number of social isolation remedy messages included to entice readers. In a recent study, cooking was linked with improved mood and sense of belonging and family [79].

Good messaging emphasizes the importance of human connections and practical ways to find and to keep them [17], albeit through video chat with friends, keeping the company of animals, or spending quiet time in a garden or a park. The messages shared in this study are another means of foraging human connections, particularly for others mulling over or seeking more company and companionship. One might cultivate a community for oneself through a carefully crafted mix of virtual and in-person activities, primarily by knowing others and solitary activities, making room for what is good by looking after yourself, and accepting and being hopeful about transitioning into open spaces. They also told others to try not to think about what the future holds or let your guard down just yet. It will be interesting to see whether and how such careful or reserved optimism shifts post-COVID-19.

We hope that the practical and thoughtful strategies that older Canadians have shared resonate with a broad array of researchers, practitioners, and program planners. There is a great need for strategies to reduce older adult social isolation. About one in four older people are still living more isolated lives [21]. Prior to our study, chronically ill older people were a socially isolated group [30,48]. They might find the messenger-advised ways to be good to your body and mind helpful for eking out a more fulsome social life. For other chronically ill older Canadians, opportunities for increased social participation and support seem to alleviate perceived isolation and loneliness [80]. Loneliness has been linked with a desire for more social, recreational, and group activities [81]. Group exercise classes and walking groups can forge social connections between older people with similar pro-fitness mindsets [82]. In addition, the virtual space known as CHIME IN brings people together to converse about topics of interest and each other [83].

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

Our study has limitations. First, it is important to note that we are sharing remedy messages collected at one point in time from Canadians. Older people’s social wants and needs are bound to vary [17]. The findings may only be relevant to older people in Canada. Moreover, as Murthy [16] points out, we need to better understand how social connectedness transpires on older people’s own terms, and for that matter, their spiritual practices. We did not find spiritual practices were predominant in the shared messages. Nonetheless, the findings of this nation-wide study offer some direction for future research. Semi-structured interviews are needed to help explore shifts, if any, in older people’s propensities for virtual versus in-person encounters with friends and family and their spiritual practices. We are equally curious about what self-selected social spaces constitute in the aftermath of COVID-19. Cross-cultural instruments like the WHOQOL-SPRB BREF [84] would help to further explore older people’s social and spiritual occupations in relation to the perceived quality of their social lives.

Among the strengths of this study were strategies from contemporaries that are suited to a variety of social palates; these should appeal to practitioners and program planners, perhaps as a conversation starter with more isolated older people. One might have reservations about recommending strategies based on a single e-survey question. In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, older Canadians helped researchers raise awareness of the detrimental effects of social isolation [9,12,19]. This year’s pressing call from the Women’s College Hospital for local, provincial, and national stakeholders to work together to identify solutions also rightly includes older Canadians [85]. Older Canadians used our e-survey space to offer contemporaries practical ways to mitigate social isolation, and rightly so. People living at risk of an infectious disease are credible purveyors of practical solutions [26]. Perhaps, then, it is not the number of questions that is important, but rather the number of responses to a resonant question. Tackling social isolation resonated with nearly 9 out of 10 of the older Canadians in this study. We are eager to learn more about what older people, practitioners, and program planners think about peer-driven remedy sharing and how to best study and communicate its impacts. With social isolation now being a post-pandemic global health concern, all such work is important work [21].

5. Conclusions

This paper shares messages from 1189 older Canadians about how to combat social isolation immediately following the COVID-19 pandemic. At least in the specific context of this study, an e-survey was a good gathering space to share ideas and insights, albeit as self-affirmations or practical strategies for seeking more social connectedness. That actionable shares came from a majority of e-survey responders is a testament to older people’s social philanthropy and other-oriented nature. We hope that researchers, practitioners, program developers, and older people themselves find solace in knowing that the bearers of these messages collectively endorsed them, regardless of their age, sex, gender identity, and varied health circumstances.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid4060053/s1. Exhibit S1: Study information and informed consent letter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L., S.v.H. and G.G.; methodology, G.L., S.v.H. and Z.G.; Software, G.L.; validation, G.L., S.v.H. and G.G.; formal analysis, H.A., M.V. and A.N.; investigation, G.L., S.v.H. and G.G.; resources, G.L. and A.N.; data curation, G.L., S.v.H. and G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L. and S.v.H.; writing—review and editing, A.N., G.G., Z.G., D.M.W. and H.A.; visualization, H.A. and A.N.; supervision, S.v.H. and D.M.W.; project administration, G.L., D.M.W. and A.N.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the RTOERO Foundation (RES0056223).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Alberta (Pro00118512 March 9, 2022 Pro00118512 REN 1 February 8, 2023; Pro00118512_REN2 January 11, 2024). The findings and the views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the University of Alberta or the RTOERO Foundation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study, and to publish this paper [Exhibit S1].

Data Availability Statement

The completely anonymized content analysis data is available upon reasonable request from G.L., the principal investigator: gaill@ualberta.ca.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. An Ad Hoc WHO Technical Consultation Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Call for Action. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010314 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public: MythBusters. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Center for Addiction and Mental Health. Coping with Stress and Anxiety. 2024. Available online: https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19/coping-with-stress-and-anxiety (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Government of Canada. Cases by Age and Gender: Figure 4. Age and Gender Distribution of COVID-19 Cases in Canada as of March 9, 2024 (n = 4,525,785); Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/current-situation.html#figure6-header (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Hobfoll, S.; Watson, P.; Bell, C.C.; Bryant, R.A.; Brymer, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Gersons, B.P.R.; de Jong, J.T.V.M.; Layne, C.M.; et al. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and Mid-Term Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry 2007, 70, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocuzzo, B.; Wrench, A.; O’Malley, C. Effects of COVID-19 on Older Adults: Physical, Mental, Emotional, Social, and Financial Problems Seen and Unseen. Cureus 2022, 14, e29493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rubeis, V.; Anderson, L.N.; Khattar, J.; de Groh, M.; Jiang, Y.; Oz, U.E.; Basta, N.E.; Kirkland, S.; Wolfson, C.; Griffith, L.E.; et al. Stressors and Perceived Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic among Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Using Data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. CMAJ Open 2022, 10, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health Research Canada. Mental Health during COVID-19 Outbreak: Poll #6—Full Report; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www.mhrc.ca/national-poll-covid/findings-of-poll-6 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Dong, L.; Yang, L. COVID-19 Anxiety: The Impact of Older Adults’ Transmission of Negative Information and Online Social Networks. Aging Health Res. 2023, 3, e100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutman, G.; de Vries, B.; Beringer, R.; Daudt, H.; Gill, P. COVID-19 Experiences and Advance Care Planning (ACP) among Older Canadians: Influence of Age, Gender and Sexual Orientation; SFU Gerontology Research Centre: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2021; Available online: http://www.sfu.ca/lgbteol.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health, September to December 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210318/dq210318a-eng.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, A.; Nicolle, J. Social Isolation and Loneliness: The New Geriatric Giants: Approach for Primary Care. Can. Fam. Physician 2020, 66, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.L.; Steinman, L.E.; Casey, E.A. Combating Social Isolation among Older Persons in a Time of Physical Distancing: The COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, V.H. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- National Institute on Ageing. Understanding Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older Canadians and How to Address It. 2022. Available online: https://cnpea.ca/images/socialisolationreport-final1.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- National Institute on Ageing; Telus Health. Pandemic Perspectives on Ageing in Canada in Light of COVID-19: Findings from a National Institute on Ageing/TELUS Health National Survey. 2020. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5f85fe24729f041f154f5668/1602616868871/PandemicPerspectives+oct13.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ooi, L.L.; Liu, L.; Roberts, K.C.; Gariépy, G.; Capaldi, C.A. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Positive Mental Health among Older Adults in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Rao, W.; Li, M.; Caron, G.; D’Arcy, C.; Meng, X. Prevalence of Loneliness and Social Isolation among Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 35, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Social Isolation and Loneliness. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/social-isolation-and-loneliness (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Ehni, H.J.; Wahl, H.W. Six Propositions against Ageism in the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagacé, M.; O’Sullivan, T.; Dangoisse, P.; Mac, M.; Oostander, S.; Doucet, A. A Case Study on Ageism during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Prepared for Employment and Social Development Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.910866/publication.html (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; United Nations Institute for Training and Research. Stakeholder Engagement. 2020. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/stakeholders (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barré, I. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A Global, Crosscutting Framework to Inform Research, Intervention Development, and Policy on Health-Related Stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumimoto, K.; Doi, T.; Makizako, H.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Kim, M.; Kurita, S.; Suzuki, T.; Shimada, H. Social Frailty Has a Stronger Impact on the Onset of Depressive Symptoms than Physical Frailty or Cognitive Impairment: A 4-Year Follow-Up Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Rodríguez-Mañaz, L. Impact of Social Isolation due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhr, S.; Reininghaus, U.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Mental Wellbeing in the German Old Age Population Largely Unaltered during COVID-19 Lockdown: Results of a Representative Survey. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, P.; Wolfson, C.; Griffith, L.; Kirkland, S.; McMillan, J.; Basta, N.; Joshi, D.; Erbas Oz, U.; Sohel, N.; Maimon, G.; et al. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Middle-aged and Older Adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, C.E.; de Jager, C.A.; Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Giannakopoulou, P.; Udeh-Momoh, C.; McKeand, J.; Price, G.; Car, J.; Majeed, A.; Ward, H.; et al. Associations of Social Isolation with Anxiety and Depression during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey of Older Persons in London, UK. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 591120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Shavit, Y.Z.; Barnes, J.T. Age Advantages in Emotional Experience Persist even under Threat from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Röhr, S.; Reininghaus, U.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Social Isolation and Loneliness during COVID-19 Lockdown: Associations with Depressive Symptoms in the German Old-Age Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menze, I.; Mueller, P.; Mueller, N.G.; Schmicker, M. Age-Related Cognitive Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic Restrictions and Associated Mental Health Changes in Germans. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Mental Health Association. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Mental Health: Heading off an Echo Pandemic; Canadian Mental Health Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://cmha.ca/brochure/covid-19-and-mental-health-heading-off-an-echo-pandemic/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All. 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/356119 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: A Survey of Canadian Older Adults; Summary of Results; Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health: Markham, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://ccsmh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/CCSMH-Social-Isolation-Survey-Results-Report-by-older-adults-ENGLISH-1.pdf (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Low, G.; Gutman, G.; Gao, Z.; França, A.; von Humboldt, S.; Vitorino, L.M.; Wilson, D.M.; Allana, H. Mentally Healthy Living after Pandemic Social Distancing: A Study of Older Canadians Reveals Helpful Anxiety Reduction Strategies. PubMed Central 2024, 24, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. 2016 Census Topic: Population and Dwelling Counts. 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/population-eng.cfm (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Grady, A.; Stinchcombe, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Older Sexual Minority Canadians in the CLSA. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Belhouari, S.; Dussault, A. A Systematic Literature Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Health of LGBTQIA+ Older Adults: Identification of Risk and Protective Health Factors and Development of a Model of Health and Disease. J. Homosex. 2024, 71, 1297–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Dictionary, Census of Population 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/index-eng.cfm (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyngäs, H. Inductive Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIVO, Version 14.23.2; Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2023. Available online: https://lumivero.com/shop/?Family=nvivo (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Chi-Squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.01.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-29 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Iftene, F.; Milev, R.; Farcas, A.; Squires, S.; Smirnova, D.; Fountoulakis, K.N. COVID-19 Pandemic: The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Life Habits in the Canadian Population. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, e871119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Canada Is the First Country to Provide Census Data on Transgender and Non-Binary People. 2022. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220427/dq220427b-eng.htm (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response. COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic. Available online: https://theindependentpanel.org (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Government of Canada. What Did Canadians Do to Maintain Their Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/what-did-canadians-do-for-mental-health-during-covid-19.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Cavallini, E.; Rosi, A.; van Vugt, F.T.; Ceccato, I.; Rapisarda, F.; Vallarino, M.; Ronchi, T.; Lecce, S. Closeness to Friends Explains Age Differences in Positive Emotional Experience during the Lockdown Period of COVID-19 Pandemic. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Ferson, S.; Mannis, A.; Bentall, R.P.; Bennett, K.M. Belongingness Challenged: Exploring the Impact on Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmann, J.; Handlovsky, I.; Lu, S.; Moullec, G.; Frohlich, K.L.; Ferlatte, O. Resilience among Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Photovoice Study. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2023, 3, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahmann, T.; du Plessis, V.; Fournier-Savard, P. Volunteering in Canada: Challenges and Opportunities during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00037-eng.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Volunteer Canada; Volunteer Management Professionals of Canada; Spinktank. The Volunteering Lens of COVID-19: Fall 2020 Survey. Impacts of COVID-19 on Volunteer Engagement. 2020. Available online: https://volunteer.ca/index.php?MenuItemID=433 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L. Positive Mental Health and Perceived Change in Mental Health among Adults in Canada during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2021, 41, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocco, A.J.; Gryspeerdt, C.; Franco, G. Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Persons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney, Y. Volunteerism. In Crisis or at a Crossroads? The Philanthropist Journal: News and Analysis for the Non-Profit Sector. 2023. Available online: https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/ResearchAndResources_DOCS/Vol%20Lens%202020%20Survey%20Results/VC_FallSurveyReport_2020_ENG_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Lachance, E.L. COVID-19 and Its Impact on Volunteering: Moving towards Virtual Volunteering. Leis. Sci. 2020, 43, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyser, M. Gender Differences in Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/statcan/45-28/CS45-28-1-2020-44-eng.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Lesser, I.A.; Nijenhuis, C.P. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physical Activity Behavior and Well-Being of Canadians. Int. J. Environ. Behav. Res. 2020, 17, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, R.V.; Newall, N.E.G.; Lawrence, B.C.; Ramsey, D.; Waddell, C.M.; Dauphinais, J. Conversations in Times of Isolation: Exploring Rural-Dwelling Older Persons’ Experiences of Isolation and Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Humboldt, S.; Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N.; Arias-Merino, E.; Ribeiro-Gonçalves, J.A.; Cabras, E.; Low, G.; Leal, I.P. The Upside of Negative Emotions: How Do Older Persons from Different Cultures Challenge Their Self-Growth during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, e648078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thauvoye, E.; Vanhooren, S.; Vandenhoeck, A.; Dezutter, J. Spirituality and Well-Being in Old Age: Exploring the Dimensions of Spirituality in Relation to Late-Life Functioning. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 2167–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornadt, A.; Albert, I.; Hoffmann, M.; Murdock, E.; Nell, J. Perceived Ageism during the COVID-19-Crisis Is Longitudinally Related to Subjective Perceptions of Aging. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Humboldt, S.; Low, G.; Leal, I. Health Service Accessibility, Mental Health and Changes in Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study with Older Persons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G. Maintaining Health and Well-Being by Putting Faith into Action during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2205–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, S. Mental Health and Psychosocial Aspects of Coronavirus Outbreak in Pakistan: Psychological Intervention for Public Mental Health Crisis. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Jannini, T.B.; Socci, V.; Pacitti, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.D. Stressful Life Events and Resilience during the COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in Italy: Association with Mental Health Outcomes and Age. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 635832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, S.H. Pandemic Disruptions of Older Adults’ Meaningful Connections: Linking Spirituality and Religion to Suffering and Resilience. Religions 2022, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upenieks, L. Religious/Spiritual Struggles and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Does “Talking Religion” Help or Hurt? Rev. Relig. Res. 2022, 64, 249–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detsky, A.S.; Bogoch, I.I. COVID-19 in Canada—The Fourth through Seventh Waves. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e224160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytle, A.; Apriceno, M.B.; Macdonald, J.; Monahan, C.; Levy, S.R. Pre-Pandemic Ageism toward Older Adults Predicts Behavioral Intentions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77, e11–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, P.; AboJabel, H. The Conceptual and Methodological Characteristics of Ageism during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Empirical Studies. Gerontologist 2022, 63, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Launches Commission to Foster Social Connection. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-11-2023-who-launches-commission-to-foster-social-connection (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Phipps, D.; Cummins, J.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W.; Cardinal, S. The Co-Produced Pathway to Impact Describes Knowledge Mobilization Processes. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2016, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, G.; Gutman, G.; Gao, Z.; França, A.; von Humboldt, S.; Vitorino, L.M.; Wilson, D.M.; Allana, H. Cooking up Calm: Design Your Menu for Mentally Healthy Living in the Later Years; RTEORO: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://rtoero.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/cooking_up_calm_singles.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Garcia, A.; Privott, C. Meal Preparation and Cooking Group Participation in Mental Health: A Community Transition. Food Stud. Interdiscip. J. 2023, 13, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. The Effects of Social Participation Restriction on Psychological Distress among Older Adults with Chronic Illness. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Bronskill, S.E.; Strauss, R.; Boblitz, A.; Guan, J.; Im, J.H.B.; Rochon, P.A.; Grunier, A.; Savage, R.D. Factors Associated with Loneliness in Immigrant and Canadian-born Older Adults in Ontario, Canada: A Population-based Study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Falk, E.B.; Kang, Y. Relationships between Physical Activity and Loneliness: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2024, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTOERO Foundation. Top 6 Reasons to CHIME IN. Available online: https://rtoero.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Top_6_Reasons_to_Chime_In_EN_FINAL-ua.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Skevington, S.M.; Gunson, K.S.; O’Connell, K.A. Introducing the WHOQOL-SRPB BREF: Developing a Short-Form Instrument for Assessing Spiritual, Religious and Personal Beliefs within Quality of Life. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women’s College Hospital. There Is a Loneliness Epidemic among Older People in Canada. Available online: https://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/there-is-a-loneliness-epidemic-among-older-adults-in-canada/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).