Changes in Need, Changes in Infrastructure: A Comparative Assessment of Rural Nonprofits Responding to COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

Conceptual Background

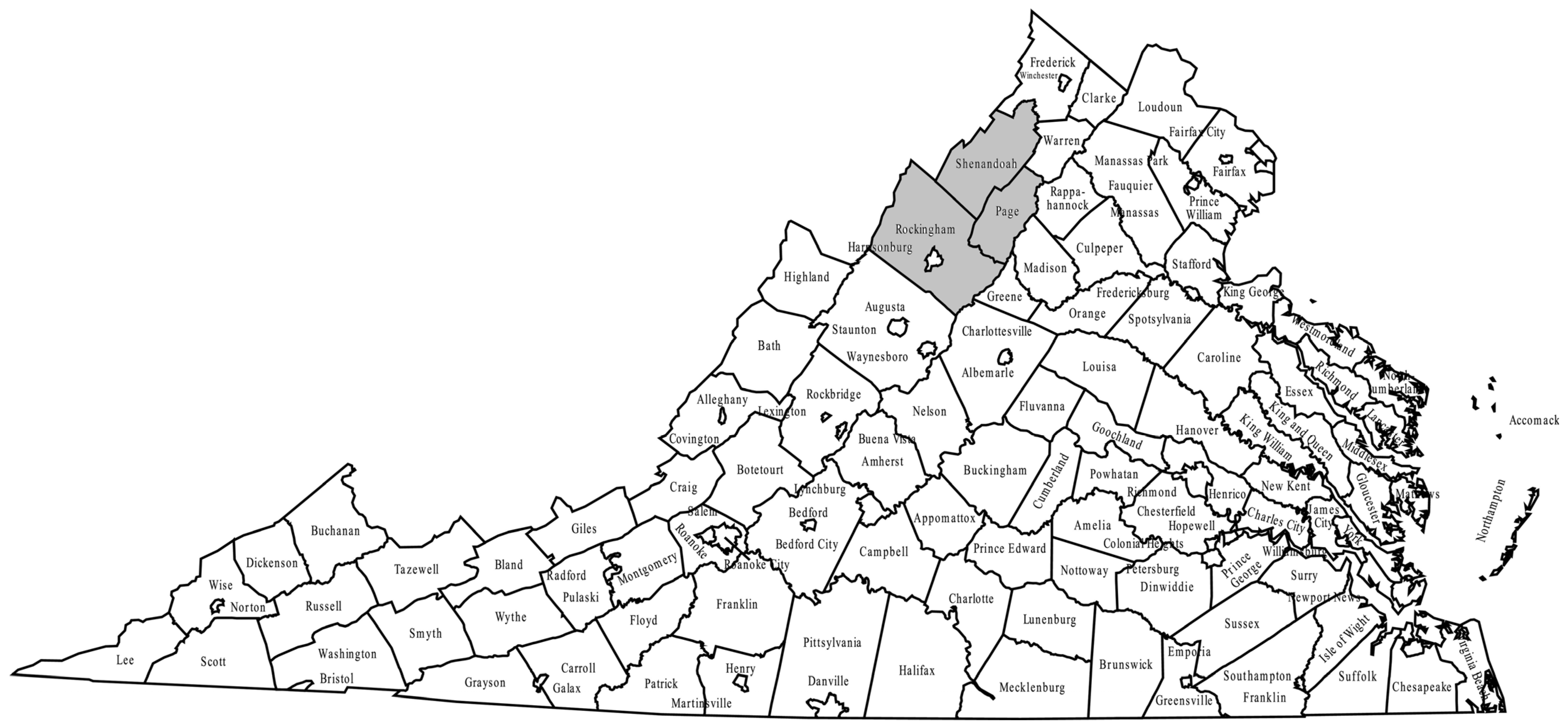

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Community Needs

3.2. Community Assets

4. Conclusions

4.1. Community Recommendations

4.1.1. Infrastructure

4.1.2. Funding and Capacity Building for Nonprofits

4.1.3. Mental Health Resources and Connection Building

4.1.4. Public Communication Strategies

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Research Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

References

- United Nations. UN/DESA Policy Brief #85: Impact of COVID-19: Perspective from Voluntary National Reviews. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-85-impact-of-covid-19-perspective-from-voluntary-national-reviews/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Pollard, M.; Mare, D. Defining Geographic Communities, Motu Economic and Public Policy Research; Foundation for Research, Science and Technology: Wellington, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, F.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, F. A Practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No.149. Med. Teach. 2022, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.F.; Rauhaus, B.M.; Webb-Farley, K. The COVID-19 pandemic: A challenge for US nonprofits’ financial stability. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2021, 33, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, K.; Stewart, A.J.; Walk, M. COVID-19 as a nonprofit workplace crisis: Seeking insights from the nonprofit workers’ perspective. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 31, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Stevens, K.; Taylor, J.A.; Morris, J.C. Are we really on the same page? An empirical examination of value congruence between public sector and nonprofit sector managers. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 26, 2424–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisance, G. Nonprofit organizations in times of COVID-19: An overview of the impact of the crisis and associated needs. Gestion 2000 2021, 38, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.R.; Brudney, J.L.; Clerkin, R.M.; Brien, P.C. At your service: Nonprofit infrastructure organizations and COVID-19. Found. Rev. 2020, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.R.; Laureano, R.M. COVID-19-related studies of nonprofit management: A critical review and research agenda. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2022, 33, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Jang, H.; Keyes, L.; Dicke, L. Nonprofit Service Continuity and Responses in the Pandemic: Disruptions, Ambiguity, Innovation, and Challenges. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.R.; Phillips, S.D. The changing and challenging environment of nonprofit human services: Implications for governance and program implementation. In Nonprofit Policy Forum; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- de Koning, R.; Egiz, A.; Kotecha, J.; Ciuculete, A.C.; Ooi, S.Z.Y.; Bankole, N.D.A.; Erhabor, J.; Higginbotham, G.; Khan, M.; Dalle, D.U.; et al. Survey Fatigue during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Neurosurgery Survey Response Rates. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 690680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Fenema, P.C.; Romme, A.G.L. Latent organizing for responding to emergencies: Foundations for research. J. Organ. Des. 2020, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Stanton, N.; Jenkins, D.; Walker, G. Coordination during multi-agency emergency response: Issues and solutions. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2011, 20, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, J.K.; van Fenema, P.C.; Faraj, S. Shots fired! Switching between practices in police work. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amandolare, S.; Bowles, J.; Gallagher, L.; Garrett, E. Essential Yet Vulnerable: NYC’s Human Services Nonprofits Face Financial Crisis during Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep25435.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Sloan, M.; Trull, L.; Malomba, M.; Akerson, E.; Atwood, K.; Eaton, M. A rural perspective on COVID-19 responses: Access, interdependence and community. J. Nonprofit Educ. Leadersh. 2022, 12, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. Rural America. 2020. Available online: https://gisportal.data.census.gov/arcgis/apps/MapSeries/index.htmlappid=7a41374f6b03456e9d138cb014711e01 (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Souch, J.M.; Cossman, J.S. A commentary on rural-urban disparities in COVID-19 testing rates per 100,000 and risk factors. J. Rural Health 2021, 37, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.J.; Horswell, R.; Hendricks, B.M.; Chu, S.; Hillegass, W.B.; Beasley, W.H.; Harper, J.R.; Kimble, W.; Rosen, C.J.; Miele, L.; et al. Higher hospitalization and mortality rates among SARS-CoV-2-infected persons in rural America. J. Rural Health 2023, 39, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dorn, A.; Cooney, R.E.; Sabin, M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the U.S. Lancet 2020, 395, 1243–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- USDA. Rural America at a Glance. 2018. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90556/eib-200.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Stat. COVID-19 Preparedness: How Ready Is Your County? 2020. Available online: https://www.statnews.com/feature/coronavirus/county-preparedness-scores/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Virginia Department of Health. Poverty in Virginia. 2023. Available online: https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/data/social-determinants-of-health/poverty/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Federation of Virginia Food Banks. Virginia Food Insecurity and Food Deserts. 2019. Available online: http://vafoodbanks.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Federation_11262013.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Health, Resources and Services Administration. Health Professional Shortage Area Mapping Tool. 2021. Available online: https://data.hrsa.gov/maps/map-tool/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Advancing Equity in Rural America. 2022. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2022/06/advancing-health-equity-in-rural-america.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Rural Health Information Hub. (n.d.). Healthcare Access in Rural Communities. Available online: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/healthcare-access (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Social Determinants of Health—Healthy People 2030|health.gov. (n.d.). Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Walters, J.E. Organizational capacity of nonprofit organizations in rural areas of the United States: A Scoping review. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2020, 44, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, A.; De Lew, N.; Chappel, A.; Aysola, V.; Zuckerman, R.; Sommers, B. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts (HP-2022-12). Office of Health Policy. 2022. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Cohen, R. Bridgespan Reports on Strengths and Challenges of Rural Nonprofits, (Oct 5) Nonprofit Quarterly. 2011. Available online: https://nonprofitquarterly.org/bridgespan-issues-important-report-on-strengths-and-challenges-of-rural-nonprofits/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Newstead, B.; Wu, P. Nonprofits in Rural America: Overcoming the Resource Gap. The Bridgespan Group. 2009. Available online: https://www.bridgespan.org/insights/nonprofits-in-rural-america-overcoming-the-resourc (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Daly, M.L.; Avant, F.R. Down-home social work: A strengths-based model for rural practice. In Rural Social Work: Building and Sustaining Community Capacity, 2nd ed.; Scales, T.L., Streeter, C.L., Cooper, H.S., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R.P.; Rice, R.E. Nonprofit organization communication, crisis planning, and strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2022, 27, e1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, K.; Branyon, B. Pivoting services: Resilience in the face of disruptions in nonprofit organizations caused by COVID-19. J. Public Nonprofit Aff. 2021, 7, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| N= | 248 | 127 |

| % white | 93.60 | 90.67 |

| % female | 82.84 | 91.00 |

| % married on in domestic partnership | 78.98 | 77.63 |

| % Bachelors degree or higher | 59.09 | 63.00 |

| Median age | 49.85 | 49.50 |

| Need Area | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Difference | Avg Rank over Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business support | 8.22 | 8.48 | +0.26 | 8.35 |

| Childcare | 5.82 | 5.45 | −0.37 | 5.64 |

| Employment | 4.03 | 4.60 | +0.57 ** (0.092) | 4.35 |

| Food/groceries access | 5.76 | 6.63 | +0.87 * (0.021) | 6.20 |

| Healthcare | 4.60 | 4.79 | +0.19 | 4.695 |

| Housing | 5.54 | 4.56 | −0.98 * (0.009) | 5.05 |

| Infrastructure | 8.35 | 8.20 | −0.15 | 8.275 |

| Mental Health | 4.90 | 4.26 | −0.64 ** (0.063) | 4.58 |

| Substance abuse | 5.20 | 4.82 | −0.38 | 5.01 |

| Technology access | 7.19 | 7.38 | +0.19 | 7.285 |

| Transportation | 6.39 | 6.83 | +0.44 | 6.61 |

| Theme | Elaboration |

|---|---|

| Increased need for internet access | The demand for faster and more reliable internet service is consistently highlighted, particularly for online learning, telehealth, and virtual communication. |

| Escalation of mental health Challenges | A significant increase in mental health problems is noted, with greater stress, anxiety, and depression observed. The strain on local healthcare facilities and community services is emphasized. |

| Impact on education | The lack of internet access and resources has created challenges for students, leading to stress in households and a greater need for technology. Educational disparities and the digital divide are evident. |

| Elevated healthcare needs | There is a perceived greater need for healthcare services, with emphasis on the challenges in accessing prompt appointments, wellness visits, and telehealth services. |

| Economic struggles | Unemployment, homelessness, and economic hardships have increased, with implications for housing affordability and overall cost of living. Business closures and supply shortages are mentioned as contributing factors. |

| Substance abuse issues | Substance abuse problems are reported to have risen, potentially linked to increased stress, unemployment, and disruptions in daily life. |

| Challenges in accessing housing | Decreased access to housing is identified as a concern, exacerbated by rising prices and changes in housing programs during the pandemic. |

| Governmental impact on the economy | Criticisms are expressed regarding the governmental response to the pandemic, with claims that decisions have negatively affected the ability to work and live. |

| Limited mental health resources | Mental health support and access are reported to be challenging, with long waiting lists and temporary closures of mental health facilities due to staff shortages. |

| Changes in employment landscape | Layoffs, changes in employment opportunities, and mistrust in workplaces are highlighted as economic challenges faced by the community. |

| Disparities in healthcare access | Issues related to access to physicians, appointments, and healthcare needs are reported, with concerns about disparities and changes in healthcare delivery. |

| Challenges in housing programs | Changes or stoppages in housing programs during the pandemic are noted as impacting the availability and affordability of housing. |

| Impacts on the older population | The older population, in particular, is reported to be still isolated, with changes in employment opportunities and neglect of healthcare needs due to fear of contracting COVID-19. |

| Transportation and healthcare access | Transportation needs are mentioned, particularly in relation to accessing healthcare services, indicating challenges in mobility and health-related travel. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sloan, M.F.; Switzer, T.; Trull, L.H.; Switzer, C.; Eaton, M.; Atwood, K.; Akerson, E. Changes in Need, Changes in Infrastructure: A Comparative Assessment of Rural Nonprofits Responding to COVID-19. COVID 2024, 4, 349-362. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4030023

Sloan MF, Switzer T, Trull LH, Switzer C, Eaton M, Atwood K, Akerson E. Changes in Need, Changes in Infrastructure: A Comparative Assessment of Rural Nonprofits Responding to COVID-19. COVID. 2024; 4(3):349-362. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSloan, Margaret F., Tina Switzer, Laura Hunt Trull, Claire Switzer, Melody Eaton, Kelly Atwood, and Emily Akerson. 2024. "Changes in Need, Changes in Infrastructure: A Comparative Assessment of Rural Nonprofits Responding to COVID-19" COVID 4, no. 3: 349-362. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4030023

APA StyleSloan, M. F., Switzer, T., Trull, L. H., Switzer, C., Eaton, M., Atwood, K., & Akerson, E. (2024). Changes in Need, Changes in Infrastructure: A Comparative Assessment of Rural Nonprofits Responding to COVID-19. COVID, 4(3), 349-362. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4030023