Service Uptake Challenges Experienced by Pasifika Communities during COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

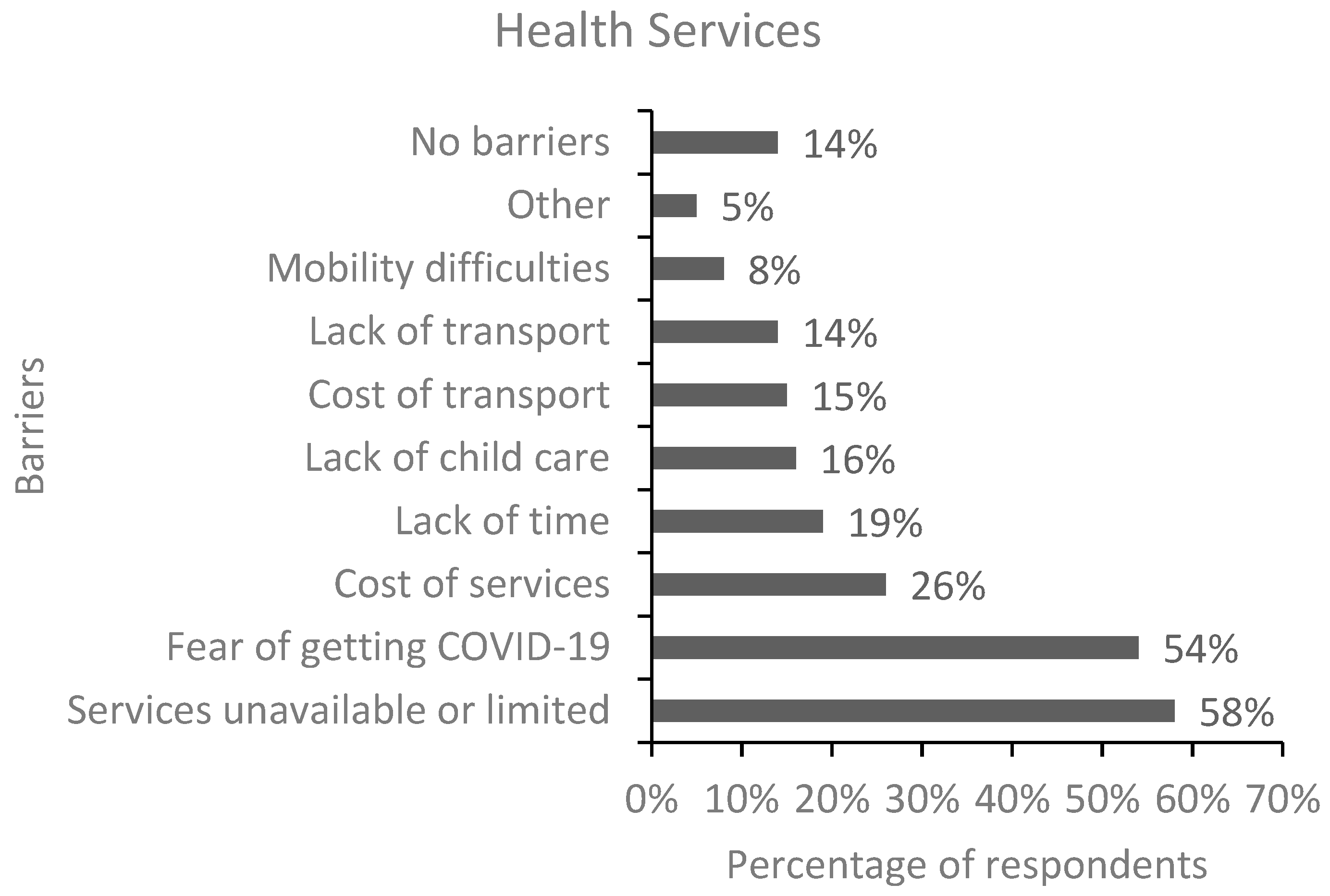

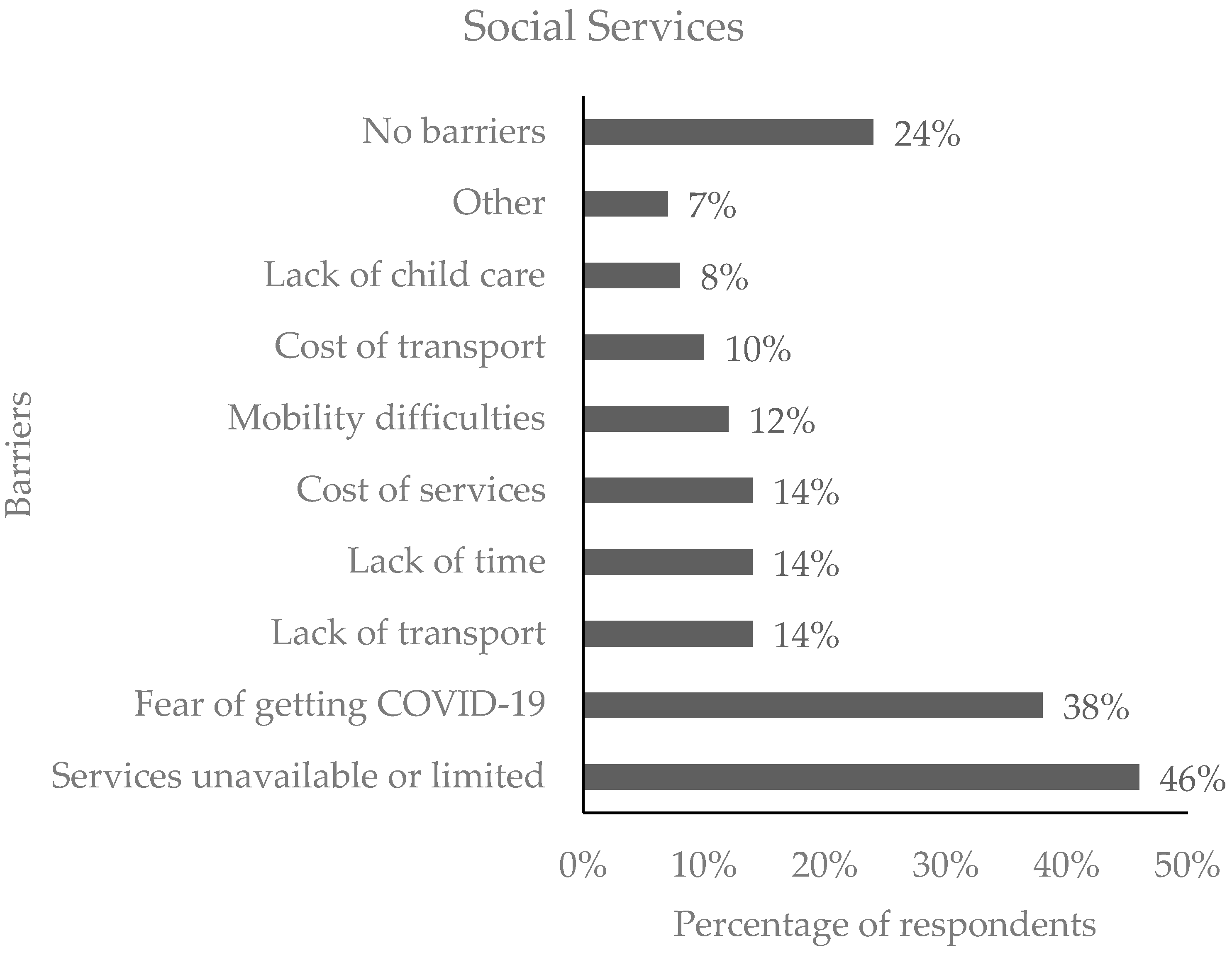

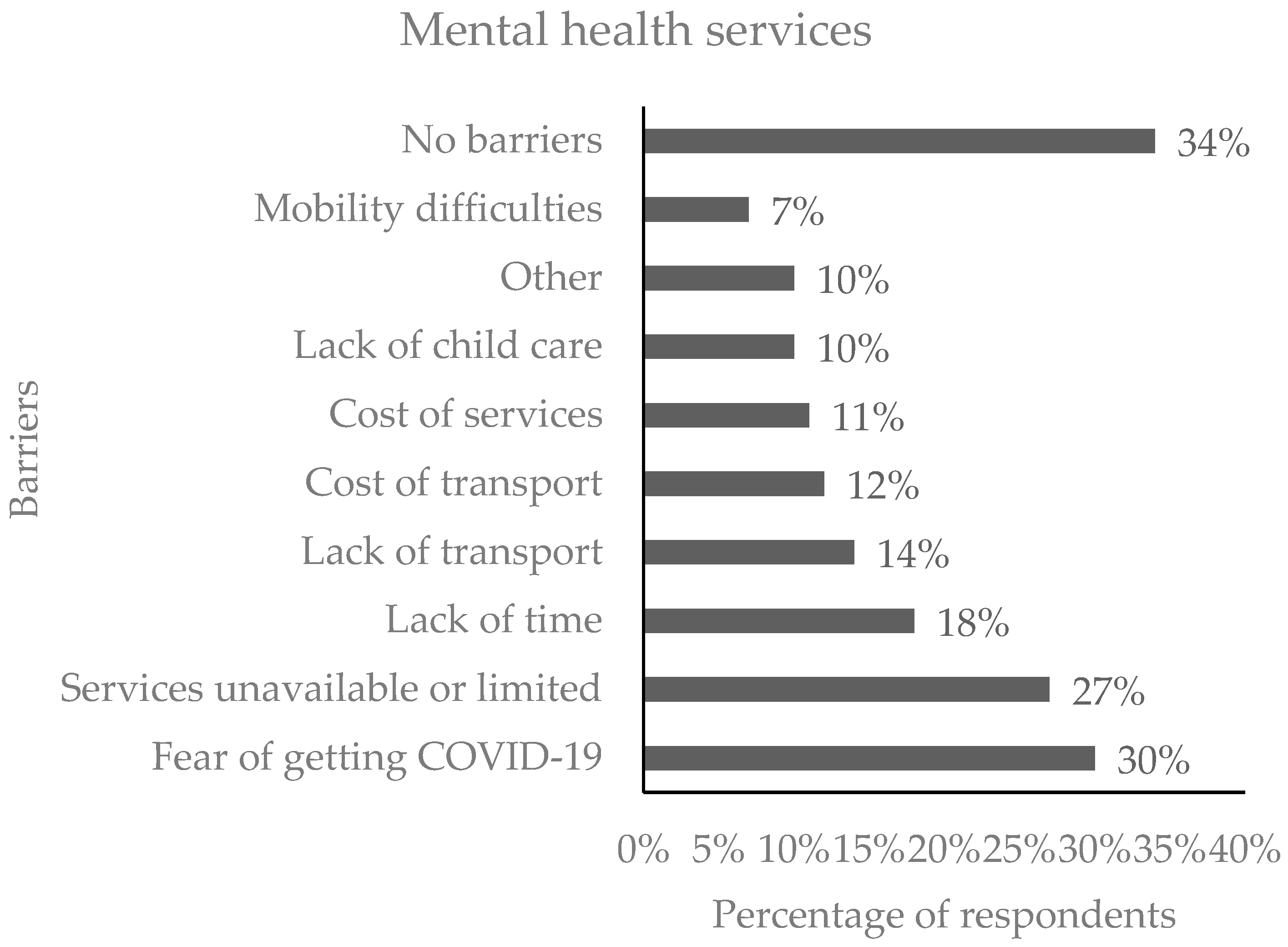

3.2. Access Barriers to Services

3.3. Employment Issues Faced by Respondents during Lockdowns

3.4. Psychosocial Wellbeing and Preparedness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Resource Center Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard. 2023. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Baker, M.G.; Wilson, N.; Anglemyer, A. Successful Elimination of COVID-19 Transmission in New Zealand. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, T. “Go Hard, Go Early”: Preliminary Lessons From New Zealand’s Response to COVID-19. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, T. Coronavirus: The Government’s COVID-19 lockdown measures have overwhelming public support, according to a poll. In Stuff; Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/121231591/coronavirus-the-governments-covid19-lockdown-measures-have-overwhelming-public-support-according-to-a-poll (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Sibley, C.G.; Greaves, L.M.; Satherley, N.; Wilson, M.S.; Overall, N.C.; Lee, C.H.J.; Milojev, P.; Bulbulia, J.; Osborne, D.; Milfont, T.L.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickens, C.M.; Hamilton, H.A.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Nigatu, Y.T.; Jankowicz, D.; Wells, S. Household- and employment-related risk factors for depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Mendolia, S.; Paloyo, A.R.; Savage, D.A.; Tani, M. Working parents, financial insecurity, and childcare: Mental health in the time of COVID-19 in the UK. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigan, K.; McGovern, M.; Plunkett, R.; Costello, S.; McDonald, C.; Hallahan, B. A longitudinal evaluation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with pre-existing anxiety disorders. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 38, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Cadigan, J.M.; Rhew, I.C. Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association With Increases in Mental Health Problems. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisitsa, E.; Benjamin, K.S.; Chun, S.K.; Skalisky, J.; Hammond, L.E.; Mezulis, A.H. Loneliness among young adults during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediational roles of social media use and social support seeking. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 39, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, A.; Hsu, L. COVID-19 and Domestic Violence: Economics or Isolation? J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2022, 43, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iob, E.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics New Zealand. Census Population and Dwelling Counts 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2018-census-population-and-dwelling-counts (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Southwick, M.; Kenealy, T.; Ryan, D. Primary Care for Pacific People: A Pacific and Health Systems Approach: Report to the Health Research Council and the Ministry of Health; Pacific Perspectives: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ioane, J.; Percival, T.; Laban, W.; Lambie, I. All-of-community by all-of-government: Reaching Pacific people in Aotearoa New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Z. Med. J. 2021, 134, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.; Vaisola-Sefo, L.; Ryan, D.; Percival, T. Why We Should Adopt a Village Model COVID-19 Response: University of Otago. Ideasroom 2021. Available online: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/ideasroom/why-we-should-adopt-a-village-model-COVID-19-response (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Officer, T.N.; Imlach, F.; McKinlay, E.; Kennedy, J.; Pledger, M.; Russell, L.; Churchward, M.; Cumming, J.; McBride-Henry, K. COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown and Wellbeing: Experiences from Aotearoa New Zealand in 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrott, A. The Rise and Rise of Pacific Healthcare—New Zealand Doctor: Rata Aotearoa. 2021. Available online: https://www.nzdoctor.co.nz/article/rise-and-rise-pacific-healthcare (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Imlach, F.; McKinlay, E.; Kennedy, J.; Pledger, M.; Middleton, L.; Cumming, J.; McBride-Henry, K. Seeking Healthcare During Lockdown: Challenges, Opportunities and Lessons for the Future. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabetkish, N.; Rahmani, A. The overall impact of COVID-19 on healthcare during the pandemic: A multidisciplinary point of view. Health Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Second Round of the National Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic; January–March 2021: Interim Report, 22 April 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- McGuinness, M.J.; Hsee, L. Impact of the COVID-19 national lockdown on emergency general surgery: Auckland City Hospital’s experience. ANZ J. Surg. 2020, 90, 2254–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Thompson, J.; Chamberlain, K.; McGuigan, K. Accessing primary healthcare during COVID-19: Health messaging during lockdown. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2022, 17, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Giridharan, N.; Cartmell, A.; Lum, D.; Signal, L.; Puloka, V.; Crossin, R.; Gray, L.; Davies, C.; Baker, M.; et al. Life during lockdown: A qualitative study of low-income New Zealanders’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Z. Med. J. 2021, 134, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fa’alii-Fidow, J. COVID-19 underscores long held strengths and challenges in Pacific health. Pac. Health Dialog 2020, 21, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Sheehan, L.; van Vreden, C.; Petrie, D.; Whiteford, P.; Sim, M.R.; Collie, A. Changes in work and health of Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffolo, M.; Price, D.; Schoultz, M.; Leung, J.; Bonsaksen, T.; Thygesen, H.; Geirdal, A.Ø. Employment Uncertainty and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Initial Social Distancing Implementation: A Cross-national Study. Glob. Soc. Welf. 2021, 8, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxholm, T.; Rivera, C.; Schirrman, K.; Hoverd, W.J. New Zealand Religious Community Responses to COVID-19 While Under Level 4 Lockdown. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Item | Response Options |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to services | What barriers to accessing health/social/mental services did you face during lockdown levels 3 and 4 (tick all that apply)? |

|

| Employment | Have you lost your job due to the lockdown? |

|

| Household income: |

| |

| Psychosocial impacts | Do you think that the pandemic has had mental health and social impacts? (depression, anxiety, loneliness, suicide, family violence). |

|

| Preparedness | Were you and your whanau (family) prepared for the COVID-19 lockdowns? |

|

| Impact | Response (n = 87) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Depression | 38 | 56.7 |

| Anxiety | 45 | 67.2 |

| Loneliness | 41 | 61.2 |

| Suicide | 29 | 43.3 |

| Family violence | 35 | 52.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nosa, V.; Sluyter, J.; Kiadarbandsari, A.; Ofanoa, M.; Heather, M.; Fa’alau, F.; Reddy, R. Service Uptake Challenges Experienced by Pasifika Communities during COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand. COVID 2023, 3, 1688-1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3110116

Nosa V, Sluyter J, Kiadarbandsari A, Ofanoa M, Heather M, Fa’alau F, Reddy R. Service Uptake Challenges Experienced by Pasifika Communities during COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand. COVID. 2023; 3(11):1688-1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3110116

Chicago/Turabian StyleNosa, Vili, John Sluyter, Atefeh Kiadarbandsari, Malakai Ofanoa, Maryann Heather, Fuafiva Fa’alau, and Ravi Reddy. 2023. "Service Uptake Challenges Experienced by Pasifika Communities during COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand" COVID 3, no. 11: 1688-1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3110116

APA StyleNosa, V., Sluyter, J., Kiadarbandsari, A., Ofanoa, M., Heather, M., Fa’alau, F., & Reddy, R. (2023). Service Uptake Challenges Experienced by Pasifika Communities during COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand. COVID, 3(11), 1688-1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3110116