When Italians Follow the Rules against COVID Infection: A Psychological Profile for Compliance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

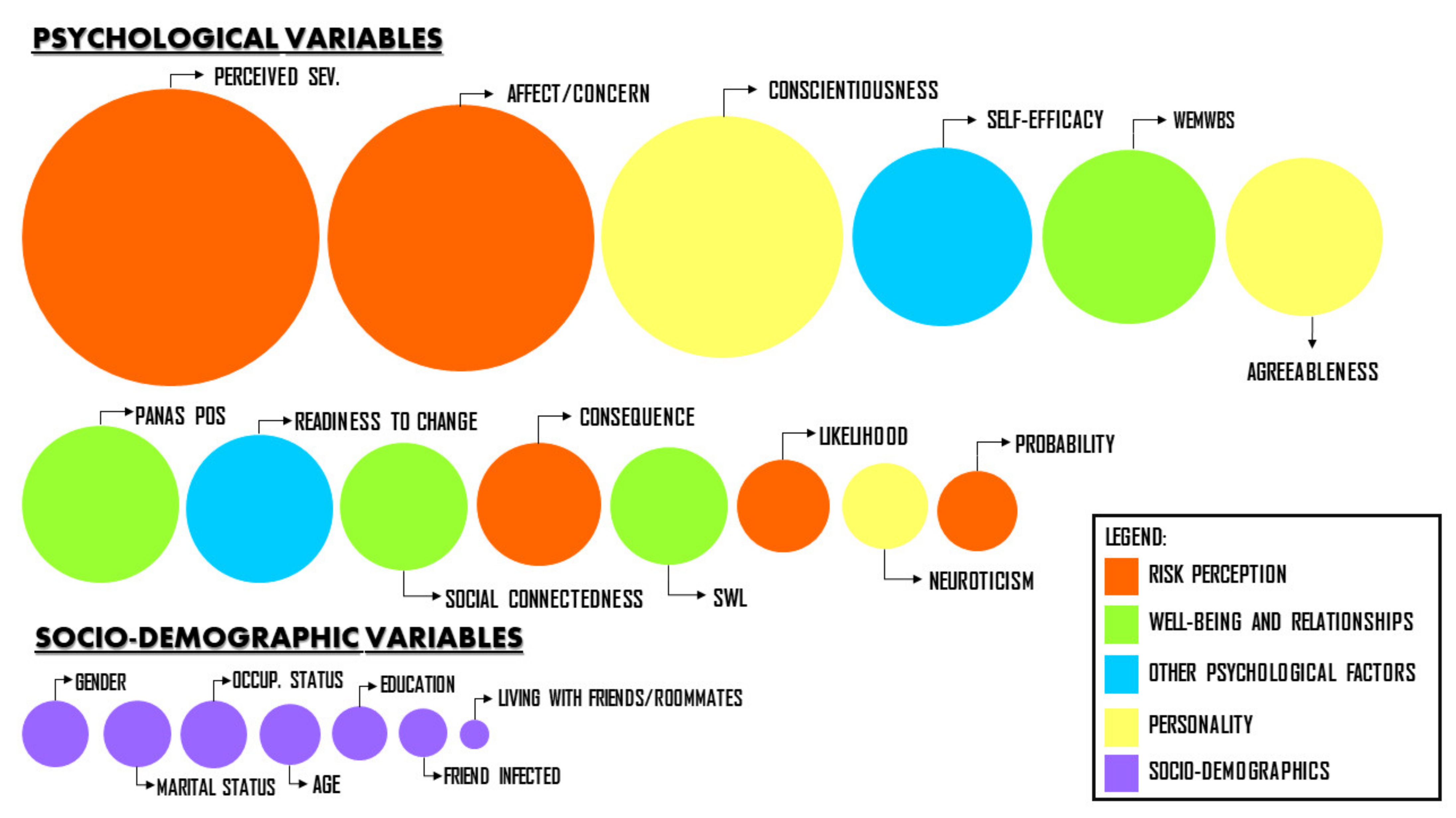

2.2. Materials

- Socio-demographic form: This was composed of questions about gender, age, education, marital status, occupational status, housing situation, knowing someone that was infected with SARS-CoV-2, and owning a pet animal.

- Reported compliance form: This was created ad hoc based on ten behavioral provisions issued by the Italian Ministry of Health against the COVID-19 pandemic. It included issues related to the degree of information (anti-COVID knowledge self-perception) and the motivation to follow the rules. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from rarely or not at all (1) to always (5) was used. The behavioral norms that Italians were asked to comply with were: the practice of washing your hands often with an alcohol-based gel; avoid close contact with people suffering from acute respiratory infections, do not touch the eyes, nose, and mouth with the hands; cover the mouth and nose with a tissue, hands, or with arms whenever you cough or sneeze; avoid taking antibiotics or antiviral medication, unless prescribed by a physician; clean surfaces with chlorine- or alcohol-based disinfectants; use a face mask if you go out or if you are caring for people who are ill; in case of doubts do not go to an emergency room, hospital, or clinic but contact your doctor. The overall reported compliance was computed by summing the score of each question regarding anti-COVID prescriptions. The variable resulted in a non-normal distribution (i.e., a kurtosis value higher than +1).

- Ten-Item Personality Inventory (I-TIPI) [30]: We used the validated Italian version, which was developed from the original scale of [31]. The scale is composed of 10 items, which evaluates five dimensions: extraversion (e.g., extraverted, enthusiastic), agreeableness (e.g., sympathetic, warm), conscientiousness (e.g., dependable, self-disciplined), emotional stability (e.g., calm, emotionally stable), and openness to experience (e.g., open to new experiences, complex). Subjects rate the extent to which certain personality traits apply to them on a scale ranging from disagree strongly (1) to agree strongly (5) on a 5-point Likert scale.

- The Self-Efficacy Scale [32]: This scale used in the Italian version [33] investigates the self-efficacy perception of the participants. The scale consists of ten items graded on a 4-point Likert scale from “Not at all true” (1) to “Exactly true” (4). The Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.76 to 0.90. The scale is unidimensional. Examples of items include: “I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events” and “I can usually handle whatever comes my way.”

- Cognitive Factors of the Risk Perception Regarding COVID-19 [34]: Cognitive factors of risk perception were assessed using five items (α = 0.79) concerning the perceived severity of COVID-19. One of these items concerns the likelihood of infection and another one concerns perceived coping efficacy. Responses were provided using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all, 5 = extremely). The items were adapted by replacing “Swine Flu” with “COVID-19.” Examples of items are: “Do you think that COVID-19 is a serious condition?” and “Do you think you are at risk of catching COVID-19?”.

- Risk Perception [35]: In the literature review conducted by Wilson and colleagues in 2019, they identified a multidimensional measure of risk perception that included affect, probability, and consequences dimensions. This scale was translated into Italian and adapted to the pandemic scenario. In particular, item 7, which asked about the likelihood that an event X will occur where they live, was changed to ask whether the likelihood that the number of people infected by COVID-19 will increase where they live since the pandemic was already in place. Item 8 was removed since it was unsuitable for our purposes (i.e., “How often do X occur where you live”). Perceived risk was elicited using nine items graded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all, 5 = extremely). In the study of Ding and colleagues, the internal reliability was α = 0.64 [36].

- Change Questionnaire (CQ) [37]: The CQ is a recently developed 12-item measure. The respondent identifies what they are considering changing (e.g., “to worry less”), and items are completed with reference to that change. Two items each represent desire, ability, reasons, need, commitment to change, and taking steps to change, and are rated on a 0 (definitely not) to 10 (definitely) scale according to the degree that each statement describes their motivation (e.g., “I want to worry less” and “I could worry less”). The total scores range from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating higher levels of change talk or motivation. The CQ has good internal consistency and test–retest reliability.

- Social Connectedness Scale—Revised (SCS-R) [38]: The Italian validation developed from the original scale of [39] investigates the participants’ experiences of closeness in interpersonal contexts, as well as problems establishing and maintaining a sense of closeness. Example items include: “I don’t feel I participate with anyone or any group” and “I am in tune with the world.” The scale is composed of twenty items on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Authors consider a mean item score equal to or greater than 3.5 (slightly agree to strongly agree) as indicating a greater tendency to feel socially connected. The SCS-R had good psychometric properties, with an average inter-item correlation of 0.66 and alpha = 0.92 in our sample.

- Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) [40]: This scale was developed by [41] in 2007, and in 2011, [40] validated the Italian version. The WEMWBS measures well-being, which is understood as positive mental health, including affective, cognitive, and well-functioning psychological aspects. The 12-item WEMWBS has 5 response categories, which are summed to provide a single score, and contains only positive aspects of mental health through a positive formulation of all items. The scale is scored by summing the responses to each item answered on a 1 to 5 Likert scale. The minimum scale score is 14 and the maximum is 70. The internal validity is α = 0.90. The reliability of the 12-item Italian version has a value of 0.86 for (Cronbach’s) alpha. Example items include: “I’ve been feeling confident” and “I’ve had energy to spare.”

- Satisfaction with Life Scale [42]: This scale, originally developed by [43], assesses global life satisfaction through five scaled items on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Concerning the content formulation, items 1 to 3 refer to satisfaction with the present, and items 4 and 5 to satisfaction with the past. The scale exhibited reliability and validity in various contexts and cultures. The Italian translation of this scale was validated by [42] and its reliability is α = 0.85. Example items are: “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” and “I am satisfied with my life.”

- Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) [44]: We used the Italian version of this scale [45], which was developed from the original scale of [44]. This self-report scale assesses two independent dimensions of positive (PA) and negative affect (NA). Participants were asked to rate how much they experienced each of the 20 emotions on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = “very slightly” to 5 = “very much.” The PA scale consists of the items excited, enthusiastic, concentrated, inspired, and determined, whereas the NA consists of the items distressed, upset, scared, nervous, and afraid. The internal reliability coefficient of the Italian version is α = 0.76.

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Reported Compliance

3.3. Psychological Variables and Reported Compliance

3.4. Reported Compliance Associations with Well-Being and Social Connectedness

3.5. Emotional Activations Related to Reported Compliance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | 2 | 10 | 5.94 | 2.07 |

| Agreeableness | 2 | 10 | 7.42 | 1.55 |

| Conscientiousness | 2 | 10 | 7.73 | 1.76 |

| Neuroticism | 2 | 10 | 6.17 | 2.05 |

| Openness | 2 | 10 | 6.64 | 1.64 |

| Self-Efficacy | 10 | 50 | 35.56 | 6.50 |

| Change Questionnaire | 12 | 60 | 54.16 | 7.58 |

| Risk: Perceived severity | 3 | 15 | 12.04 | 1.94 |

| Risk: Coping efficacy | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 0.94 |

| Risk: Likelihood of infection | 1 | 5 | 2.67 | 0.96 |

| Risk: Affect/Concern | 5 | 25 | 16.18 | 4.74 |

| Risk: Probability | 2 | 10 | 6.68 | 1.78 |

| Risk: Consequence | 2 | 10 | 6.23 | 2.15 |

| WEMWBS | 12 | 60 | 41.41 | 6.63 |

| SWL | 5 | 25 | 15.78 | 4.62 |

| Social Connectedness | 22 | 120 | 83.50 | 16.69 |

| Positive Affect | 10 | 50 | 30.17 | 7.36 |

| Negative Affect | 10 | 49 | 24.07 | 7.15 |

References

- Wright, L.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Predictors of self-reported adherence to COVID-19 guidelines. A longitudinal observational study of 51,600 UK adults. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mækelæ, M.J.; Reggev, N.; Dutra, N.B.; Tamayo, R.M.; Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Klevjer, K.; Pfuhl, G. Perceived efficacy of COVID-19 restrictions, reactions and their impact on mental health during the early phase of the outbreak in six countries. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; Ahmed, O.; Aibao, Z.; Hanbin, S.; Siyu, L.; Ahmad, A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Salas, S.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Romero-Martín, M.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Psycho-emotional approach to the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A cross-sectional observational study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Li, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. The psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on medical staff and the general public. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S.; Kleczkowski, A. Controlling epidemic spread by social distancing: Do it well or not at all. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdelrahman, M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of arab residents of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscese, G.; Lacetera, N.; Macis, M.; Tonin, M. Expectations, Reference Points, and Compliance with COVID-19 Social Distancing Measures; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, K.R.; Valle, S.Y.D. A meta-analysis of the association between gender and protective behaviors in response to respiratory epidemics and pandemics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, Q.; Cowling, B.; Lam, W.T.; Ng, M.W.; Fielding, R. Situational awareness and health protective responses to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strickhouser, J.E.; Zell, E.; Krizan, Z. Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2017, 36, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, A.M.; Corr, P.J. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United Kingdom: A personality-based perspective on concerns and intention to self-isolate. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagov, P.S. Adaptive and dark personality in the COVID-19 pandemic: Predicting health-behavior endorsement and the appeal of public-health messages. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 12, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, P.; Ajelli, M.; Merler, S. Risk perception and effectiveness of uncoordinated behavioral responses in an emerging epidemic. Math. Biosci. 2012, 238, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppin, A.; Aro, A.R. Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: Theoretical foundations of current empirical research. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wise, T.; Zbozinek, T.D.; Michelini, G.; Hagan, C.C.; Mobbs, D. Changes in Risk Perception and Self-Reported Protective Behaviour during the First Week of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, E.B.; Reinders Folmer, C.; Kuiper, M.E.; Olthuis, E.; Brownlee, M.; Fine, A.; van Rooij, B. Mitigating COVID-19 in a Nationally Representative UK Sample: Personal Abilities and Obligation to Obey the Law Shape Compliance with Mitigation Measures; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, B.; de Bruijn, A.L.; Reinders Folmer, C.; Kooistra, E.B.; Kuiper, M.E.; Brownlee, M.; Olthuis, E.; Fine, A. Compliance with COVID-19 Mitigation Measures in the United States; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zettler, I.; Schild, C.; Lilleholt, L.; Böhm, R. The role of personality in COVID-19 related perceptions, evaluations, and behaviors: Findings across five samples, nine traits, and 17 criteria. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2020, 10, 19485506211001680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogg, T.; Milad, E. Demographic, personality, and social cognition correlates of coronavirus guideline adherence in a U.S. Sample. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenwong, B.; Kwan, A.; Pursiainen, V. Social connections with COVID-19–affected areas increase compliance with mobility restrictions. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.S.; Matkovic, J.; Faasse, K.; Geers, A.L. The role of attitudes, affect, and income in predicting COVID-19 behavioral intentions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders Folmer, C.; Kuiper, M.E.; Olthuis, E.; Kooistra, E.B.; de Bruijn, A.L.; Brownlee, M.; Fine, A.; van Rooij, B. Compliance in the 1.5 Meter Society: Longitudinal Analysis of Citizens’ Adherence to COVID-19 Mitigation Measures in a Representative Sample in the Netherlands; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harper, C.A.; Satchell, L.P.; Fido, D.; Latzman, R.D. Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, B.; Palmer, C.A. Psychological correlates of news monitoring, social distancing, disinfecting, and hoarding behaviors among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krekel, C.; Swanke, S.; De Neve, J.-E.; Fancourt, D. Are Happier People More Compliant? Global Evidence from Three Large-Scale Surveys During COVID-19 Lockdowns; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, J.; Sheen, G.C.-H. Voluntary adoption of social welfare-enhancing behavior: Mask-wearing in Spain during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiorri, C.; Bracco, F.; Piccinno, T.; Modafferi, C.; Battini, V. Psychometric properties of a revised version of the ten item personality inventory. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 31, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, M.; Schwarzer, R. Self-efficacy as a resource factor in stress appraisal processes. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Hemisphere Publishing Corp: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-1-56032-269-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia, L.; Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Italian Adaptation of the General Self Efficacy Scale: Self-Efficacy Generalized. Available online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/selfscal.htm (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Zani, B. A social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk perception and recommended behaviors in Italy. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.S.; Zwickle, A.; Walpole, H. Developing a broadly applicable measure of risk perception. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Du, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, X.; Liu, Q. Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its related factors among college students in China during quarantine. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Johnson, W.R. A natural language screening measure for motivation to change. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capanna, C.; Stratta, P.; Collazzoni, A.; D’Ubaldo, V.; Pacifico, R.; Di Emidio, G.; Ragusa, M.; Rossi, A. Social connectedness as resource of resilience: Italian validation of the social connectedness scale—revised. J. Psychopathol. 2013, 19, 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.M.; Robbins, S.B. Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J. Couns. Psychol. 1995, 42, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremigni, P.; Stewart-Brown, S. Una misura del benessere mentale: Validazione italiana della Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS). G. Ital. Psicol. 2011, 38, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Measuring adolescent life satisfaction: Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of italian adolescents and young adults. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 34, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terraciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Factorial and construct validity of the italian positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joinson, A.N. Self-disclosure in computer-mediated communication: The role of self-awareness and visual anonymity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinson, A. Social desirability, anonymity, and internet-based questionnaires. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1999, 31, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Reazione dei Cittadini al Lockdown 5–21 Aprile 2020 Report No. 243357; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bish, A.; Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kroencke, L.; Geukes, K.; Utesch, T.; Kuper, N.; Back, M.D. Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Personal. 2020, 89, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, E.M.W. Personality influences in appraisal–emotion relationships: The role of neuroticism. J. Pers. 2010, 78, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. Predicting adaptive and maladaptive responses to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: A prospective longitudinal study. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, R.; Holman, E.A.; Silver, R.C. The importance of the neighborhood in the 2014 ebola outbreak in the United States: Distress, worry, and functioning. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihashi, M.; Otsubo, Y.; Yinjuan, X.; Nagatomi, K.; Hoshiko, M.; Ishitake, T. predictive factors of psychological disorder development during recovery following SARS outbreak. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, P.S.F.; Cheung, Y.T.; Chau, P.H.; Law, Y.W. The impact of epidemic outbreak: The case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis, J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2010, 31, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B.; Yang, A.; Dou, K.; Wang, L.-X.; Zhang, M.-C.; Lin, X.-Q. Chinese public’s knowledge, perceived severity, and perceived controllability of COVID-19 and their associations with emotional and behavioural reactions, social participation, and precautionary behaviour: A national survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Tambelli, R.; Casagrande, M. The Italians in the time of coronavirus: Psychosocial aspects of the unexpected COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Abukhalaf, A.A.; Alomar, A.A.; Sattar, K.; Klonoff, D.C. COVID-19 pandemic: Impact of Quarantine on medical students’ mental wellbeing and learning behaviors. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S43–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satici, B.; Saricali, M.; Satici, S.A.; Griffiths, M.D. Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: Serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnakew, Z.; Asrese, K.; Andualem, M. Community risk perception and compliance with preventive measures for COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2887–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, A.F.; BaniMustafa, A.; Alessa, Y.M.; Almutairi, S.B.; Almaleh, Y. Public trust and compliance with the precautionary measures against COVID-19 employed by authorities in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xin, M.; Dong, W.; Zhou, L.; Hou, Q.; Li, F.; Sun, G.; Zheng, Z.; Yuan, J.; et al. Self-reported compliance with personal preventive measures among chinese factory workers at the beginning of work resumption following the COVID-19 outbreak: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattay, P.; Michalski, N.; Domanska, O.M.; Kaltwasser, A.; Bock, F.D.; Wieler, L.H.; Jordan, S. Differences in risk perception, knowledge and protective behaviour regarding COVID-19 by education level among women and men in Germany. Results from the COVID-19 snapshot monitoring (COSMO) study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevorach, T.; Cohen, J.; Apter, A. Keep calm and stay safe: The relationship between anxiety and other psychological factors, media exposure and compliance with COVID-19 regulations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age | 27.88 (10.33) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16.3% |

| Female | 83.7% |

| Yearly Income (EUR) | |

| <10 k | 52.8% |

| 10–40 k | 38.6% |

| 40–70 k | 6.1% |

| 70–120 k | 2.1% |

| >120 k | 0.4% |

| Education | |

| Secondary school | 6.7% |

| High school | 49.9% |

| Bachelor degree | 22.0% |

| Master’s degree | 16.9% |

| University master | 2.8% |

| Ph.D. or other specialization | 1.8% |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 37.5% |

| In a relationship (without cohabiting) | 39.3% |

| Married or cohabiting | 21.4% |

| Divorced | 1.5% |

| Widowed | 0.3% |

| Occupational Status | |

| Unemployed | 15.1% |

| Student | 48.4% |

| Self-employed | 10.0% |

| Public employee | 5.4% |

| Permanent employee | 19.4% |

| Retired | 1.7% |

| Housing Condition * | |

| Alone | 8.4% |

| With partner | 20.4% |

| With family | 67.2% |

| Friends/Roommates | 9.5% |

| Elderly or frail people | 10.3% |

| Children | 8.6% |

| Knowing Someone Infected * | |

| No | 54.3% |

| Acquientance | 34.8% |

| Family member | 7.0% |

| Friend | 9.7% |

| Yes, me | 0.8% |

| Variable | χ2 | p | Effect Size a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.24 | 0.001 | 0.10 |

| Gender | 17.93 | 0.001 | 0.11 |

| Yearly Income | 4.65 | 0.33 | n.c. |

| Education | 12.32 | 0.031 | 0.09 |

| Marital Status | 19.32 | 0.001 | 0.11 |

| Occupational Status | 18.08 | 0.003 | 0.11 |

| Housing Condition | |||

| Alone | 0.93 | 0.33 | n.c. |

| With partner | 3.16 | 0.075 | n.c. |

| With family | 0.006 | 0.94 | n.c. |

| Friends/roommates | 4.14 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| Elderly or frail people | 0.61 | 0.44 | n.c. |

| Children | 2.97 | 0.09 | n.c. |

| Knowing Someone Infected | |||

| No | 0.29 | 0.59 | n.c. |

| Acquaintance | 0.24 | 0.62 | n.c. |

| Family member | 0.016 | 0.90 | n.c. |

| Friend | 9.67 | 0.002 | 0.08 |

| Yes, me | 0.55 | 0.46 | n.c |

| Variable | Reported Compliance Level | n | Mean | Student’s t | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | <Median | 876 | 7.26 | −4.48 *** | −0.26 |

| >Median | 680 | 7.61 | |||

| Conscientiousness | <Median | 876 | 7.47 | −6.62 *** | −0.39 |

| >Median | 680 | 8.06 | |||

| Neuroticism | <Median | 876 | 6.28 | 2.38 * | 0.14 |

| >Median | 680 | 6.03 | |||

| Self-efficacy | <Median | 876 | 34.86 | −4.85 *** | −0.29 |

| >Median | 680 | 36.46 | |||

| Risk: Perceived severity | <Median | 876 | 11.69 | −8.21 *** | −0.48 |

| >Median | 680 | 12.49 | |||

| Risk: Coping efficacy | <Median | 876 | 3.49 | 0.97 ns | 0.06 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.44 | |||

| Risk: Likelihood of infection | <Median | 876 | 2.62 | −2.55 ** | −0.15 |

| >Median | 680 | 2.74 | |||

| Risk: Affect/Concern | <Median | 876 | 15.41 | −7.34 *** | −0.43 |

| >Median | 680 | 17.16 | |||

| Risk: Probability | <Median | 876 | 6.59 | −2.28 * | −0.13 |

| >Median | 680 | 6.79 | |||

| Risk: Consequence | <Median | 876 | 6.07 | −3.43 *** | −0.20 |

| >Median | 680 | 6.44 |

| Variable | Reported Compliance Level | n | Mean | Student’s t | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEMWBS | <Median | 876 | 40.60 | −5.53 *** | −0.28 |

| >Median | 680 | 42.45 | |||

| SWL | <Median | 876 | 15.39 | −3.81 *** | −0.19 |

| >Median | 680 | 16.28 | |||

| Social connectedness | <Median | 876 | 81.87 | −4.39 *** | −0.22 |

| >Median | 680 | 85.60 |

| Variable | Reported Compliance Level | n | Mean | Student’s t | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | <Median | 876 | 29.34 | −5.10 *** | −0.26 |

| >Median | 680 | 31.24 | |||

| Negative affect | <Median | 876 | 24.24 | 1.10 ns | 0.05 |

| >Median | 680 | 23.84 |

| Variable | Reported Compliance Level | n | Mean | Student’s t | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determined | <Median | 876 | 3.13 | −3.51 *** | −0.17 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.31 | |||

| Active | <Median | 876 | 3.00 | −4.71 *** | −0.24 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.23 | |||

| Interested | <Median | 876 | 3.29 | −5.04 *** | −0.26 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.54 | |||

| Attentive | <Median | 876 | 3.18 | −5.74 *** | −0.29 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.47 | |||

| Enthusiastic | <Median | 876 | 2.75 | −2.48 * | −0.13 |

| >Median | 680 | 2.89 | |||

| Concentrated | <Median | 876 | 2.78 | −5.31 *** | −0.27 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.05 | |||

| Strong | <Median | 876 | 2.94 | −3.64 *** | −0.18 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.13 | |||

| Inspired | <Median | 876 | 2.89 | −2.22 * | −0.11 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.01 | |||

| Proud | <Median | 876 | 2.87 | −3.60 *** | −0.18 |

| >Median | 680 | 3.08 |

| Variable | Reported Compliance Level | n | Mean | Student t | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scared | <Median | 876 | 2.41 | −2.58 ** | −0.13 |

| >Median | 680 | 2.55 | |||

| Guilty | <Median | 876 | 1.54 | 1.94 * | 0.10 |

| >Median | 680 | 1.45 | |||

| Ashamed | <Median | 876 | 1.56 | 3.36 *** | 0.17 |

| >Median | 680 | 1.41 | |||

| Irritable | <Median | 876 | 2.91 | 1.94 * | 0.10 |

| >Median | 680 | 2.80 | |||

| Hostile | <Median | 876 | 1.97 | 4.02 *** | 0.20 |

| >Median | 680 | 1.77 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duradoni, M.; Fiorenza, M.; Guazzini, A. When Italians Follow the Rules against COVID Infection: A Psychological Profile for Compliance. COVID 2021, 1, 246-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid1010020

Duradoni M, Fiorenza M, Guazzini A. When Italians Follow the Rules against COVID Infection: A Psychological Profile for Compliance. COVID. 2021; 1(1):246-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid1010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuradoni, Mirko, Maria Fiorenza, and Andrea Guazzini. 2021. "When Italians Follow the Rules against COVID Infection: A Psychological Profile for Compliance" COVID 1, no. 1: 246-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid1010020

APA StyleDuradoni, M., Fiorenza, M., & Guazzini, A. (2021). When Italians Follow the Rules against COVID Infection: A Psychological Profile for Compliance. COVID, 1(1), 246-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid1010020