Navigating Work Career through Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work Values Ethic

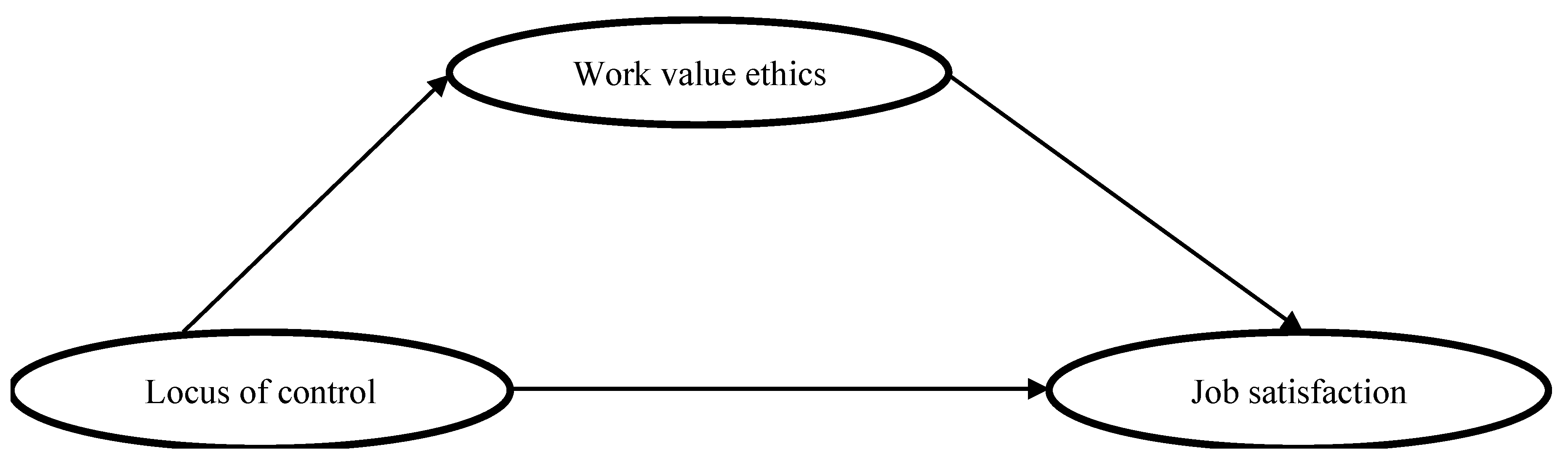

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Indicators of Self-Concept

1.1.1. Locus of Control

1.1.2. Work Values Ethic

1.2. Job Satisfaction—Indicator of Well-Being

1.3. The Relationship between Locus of Control, Job Satisfaction, and Work Values Ethic

- (1)

- Beliefs about the connection between the self and the goal (control expectancy: ‘When I want to do something, I can’);

- (2)

- Beliefs about the association between the self and the means for achieving the goal (capacity beliefs: ‘I have the capabilities to do something’); and

- (3)

- Beliefs about the utility of a given means for achieving a goal (causality beliefs: ‘I believe my effort will lead to goal achievement’ vs. ‘I believe other factors will lead to goal achievement’) ([29], p. 259).

1.3.1. Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction

1.3.2. Locus of Control and Work Values Ethic

1.3.3. Work Values Ethic and Job Satisfaction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Careermetis. 21st Century Workplace Changes and Challenges. 2017. Available online: https://www.careermetis.com/21st-century-workplace-changes-challenges/ (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Chatzky, J. Job-Hopping Is on the Rise. Should you Switch Roles to Make More Money? 2018. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/better/business/job-hopping-rise-should-you-consider-switching-roles-make-more-ncna868641 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Morgan, J. 5 Reasons Why Long-Term Employment Is Dead (and Never Coming Back). 2014. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jacobmorgan/2014/03/20/5-reasons-why-long-term-employment-is-dead-and-never-coming-back/ (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Doyle, A. How Often Do People Change Jobs? 2018. Available online: https://www.thebalancecareers.com/how-often-do-people-change-jobs-2060467 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Young, J.R. How Many Times Will People Change Jobs? The Myth of the Endlessly-Job-Hopping Millennial. 2017. Available online: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-07-20-how-many-times-will-people-change-jobs-the-myth-of-the-endlessly-job-hopping-millennial (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Kuhn, K. The Rise of the Gig Economy and Implications for Understanding Work and Workers. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S. Human Resource Management and the COVID-19 Crisis: Implications, Challenges, Opportunities and Future Organizational Directions. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.D. Understanding the Impact of Personality Traits on Individuals’ Turnover Decisions: A Meta-Analytic Path Model. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 309–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.A. The Big Five Career Theories. In International Handbook of Career Guidance; Athanasou, J.A.E., Van, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Callanan, G.A.; Perri, D.F.; Tomkowicz, S.M. Career Management in Uncertain Times: Challenges and Opportunities. Career Dev. Q. 2017, 65, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The Theory and Practice of Career Construction. In Career Development and Counselling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Almund, M.; Duckworth, A.L.; Heckman, J.; Kautz, T. Personality Psychology and Economics (IZA Discussion Paper No. 5500). 2011. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16822 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Borghans, L.; Duckworth, A.L.; Heckman, J.J.; Weel, B.T. The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits. J. Hum. Resour. 2008, 43, 972–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Ollo-Lopez, A.; Bayo-Moriones, A.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Disentangling the Relationship between High-Involvement-Work-Systems and Job Satisfaction. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 620–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Asthana, P.K. An Empirical Study of Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D.E.A. Theory of Vocational Development. Am. Psychol. 1953, 8, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P.J.; Taber, B.J. Career Construction and Subjective Well-Being. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W.; Ryan, K. A Meta-Analytic Review of Attitudinal and Dispositional Predictors of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jam, F.A.; Donia, M.B.L.; Raja, U.; Ling, C.H. A time-lagged study on the moderating role of overall satisfaction in perceived politics: Job outcomes relationships. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, J.; Schmidt, K.; Parkes, C.; van Dick, K. Taking a Sickie’: Job Satisfaction and Job Involvement as Interactive Predictors of Absenteeism in a Public Organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, L.M.; Judge, T.A. Employee Attitudes and Job Satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.; Ilies, R.; Johnson, E. Relationship of Personality Traits and Counterproductive Work Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Job Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, L.C.; Fabi, B.; Lacoursière, R.; Raymond, L. The Role of Supervisory Behavior, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment on Employee Turnover. J. Manag. Organ. 2016, 22, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T.Y. Person-Career Fit and Employee Outcomes among Research and Development Professionals. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1857–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized Expectancies for Internal versus External Control of Renforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, A.J.; Scott, D. Work Values Ethic, GNP Per Capita and Country of Birth. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerwagen, J.; Kelly, K.; Kampschroer, K. The Changing Nature of Organization, Work and Workplace. 2016. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/changing-nature-organizations-work-and-workplace (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Shogren, K.A.; Wehmeyer, M.L.; Palmer, S.B.; Forber-Pratt, A.J.; Little, T.J.; Lopez, S. Causal Agency Theory: Reconceptualizing a Functional Model of Self-Determination. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2015, 50, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C. The Dispositional Causes of Job Satisfaction: A Core Evaluations Approach. Res. Organ. Behav. 1997, 19, 151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, B.M.; Randel, A.E.; Collins, B.J.; Johnson, R.E. Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. The Individual and Congruence Effects of Core Self-Evaluation on Supervisor-Subordinate Guanxi and Job Satisfaction. J. Manag. Organ. 2014, 20, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, P. Locus of Control as a Predictor of Job Satisfaction among the Employees of Textile Industry. J. Organ. Hum. Behav. India 2015, 4, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, F.; Ren, S.; Di, Y. Locus of Control, Psychological Empowerment and Intrinsic Motivation Relation to Performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Schurer, S. Two Economists’ Musings on the Stability of Locus of Control. Econ. J. 2013, 123, 358–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, D.; Kassenboehmer, S.; Sinning, M.G. Locus of Control and Savings. J. Bank. Financ. 2016, 73, 113–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadsell, L. Achievement Goals, Locus of Control and Academic Success in Economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Eby, L.T. Locus of Control at Work: A Meta-Analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 1057–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, A.; McGee, P. Search, Effort, and Locus of Control. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2016, 126, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruk-Lee, V.; Khoury, H.A.; Nixon, A.E.; Goh, A.; Spector, P.E. Replicating and Extending Past Personality/Job Satisfaction Meta-Analyses. Hum. Perform. 2009, 22, 156–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G.; Paul, A.; St. John, N. On Developing a General Index of Work Commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993, 42, 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Duxbury, L.E.; Higgins, C.A. A comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public sector, and parapublic sector employees. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Bond, M.; Heaven, P.; Hilton, D.; Lobel, T.; Masters, J. A Comparison of Protestant Work Ethic Beliefs in Thirteen Nations. J. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 133, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C. Work Value Congruence and Intrinsic Career Success: The Compensatory Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Perceived Organizational Support. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, F.J.; Xiao, S. Work Values, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2144–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, M. Organizational Conditioning of Job Satisfaction: A Model of Job Satisfaction. Contemp. Econ. 2017, 11, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazioglu, S.; Tansel, A. Job Satisfaction in Britain: Individual and Job Related Factors. Appl. Econ. 2002, 38, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Serrano, L.; Cabral-Vieira, J.A. Low Pay, Higher Pay and Job Satisfaction within the European Union: Empirical Evidence from Fourteen Countries; IZA Discussion Paper No. 1558; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in social exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 276–299. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlin, D.B.; Coster, E.A.; Robert, W.; Rice, R.W.; Alison T. Cooper, A.T. Facet Importance and Job Satisfaction: Another Look at the Range-of-Affect Hypothesis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 16, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B.B. The Motivation to Work, 2nd ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through Design of Work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Cohen-Charash, Y. The Dispositional Approach to Job Satisfaction: More than a Mirage, but Not yet an Oasis: Comment. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagie, A.; Elizur, D.; Koslowsky, M. Work Values: A Theoretical Overview and a Model of Their Effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, B.J.; Stockton, H.; Wagner, D.; Walsh, B. The Future of Work: The Augmented Workforce. 2017. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/human-capital-trends/2017/future-workforce-changing-nature-of-work.html (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Leong, F.T.L.; Huang, J.L.; Mak, S. Protestant Work Ethic, Confucian Values, and Work-Related Attitudes in Singapore. J. Career Assess. 2014, 22, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of Core Self-Evaluations Traits—Self-Esteem, Generalized Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and Emotional Stability with Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangai, K.N.; Mahakud, G.C.; Sharma, V. Association between Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction in Employees: A Critical Review. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2016, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.P.; Dubey, A.K. Role of Stress and Locus of Control in Job Satisfaction Among Middle Managers. IUP J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 10, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.C.; Silverthorne, C. The impact of locus of control on job stress, job performance and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayashreea, L.; Jagdischchandrab, V. Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: PSU Employees. Serb. J. Manag. 2011, 6, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, A.; Mubeen, A.S.; Ghabshi, S.A. A Study on Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction in Semi-Government Organizations in Sultanate of Oman. SIJ Trans. Ind. Financ. Bus. Manag. IFBM 2013, 1, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Delaney, L.; Egan, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Childhood self-control and unemployment throughout the life span: Evidence from two British cohort studies. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.C.; Tipu, S.A.A. An Empirical Alternative to Sidani and Thornberry’s (2009) “Current Arab Work Ethic”: Examining the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile in an Arab Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoorn, R.; Maseland, A. Does a Protestant Work Ethic Exist? Evidence from the Well-Being Effect of Unemployment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 91, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grysman, A. Collecting Narrative Data on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 29, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, M.A.; Tannenbaum, S.I.; Mathieu, J.E.; Maynard, M.T. A Cross-Level Investigation of Informal Field-Based Learning and Performance Improvements. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huseman, R.; Hatfield, J.; Miles, E. A New Perspective on Equity Theory: The Equity Sensitivity Construct. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussner, T.; Strobl, A.; Veider, V.; Matzler, K. The Effect of Work Ethic on Employees’ Individual Innovation Behavior. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S. What the Rise of the Freelance Economy Means for the Future of Work. 2015. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-lund/freelance-economy-future-work_b_8420866.html (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Martin, L.; Hauret, L.; Fuhrer, C. Digitally Transformed Home Office Impacts on Job Satisfaction, Job Stress and Job Productivity: COVID-19 Findings. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E. Career networks in shock: An Agenda for in-COVID/Post-COVID Career Related Social Capital. Merits 2021, 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus of Control | 282 | 10.482 | 4.853 | 0 | 21 |

| Work Values Ethic | 282 | 3.374 | 0.474 | 2.2 | 5 |

| Job Satisfaction | 282 | 3.640 | 0.975 | 1 | 5 |

| Variable | Factor1 | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|

| Work Values Ethic | ||

| Most people who don’t succeed in life are just plain lazy | 0.732 | 0.372 |

| A distaste for hard work usually reflects a weakness of character | 0.611 | 0.621 |

| Any person who is able and willing to work hard has a good chance of succeeding | 0.733 | 0.341 |

| People who fail at a job have usually not tried hard enough | 0.746 | 0.349 |

| If one works hard, one is likely to make a good life for oneself | 0.778 | 0.297 |

| Job Satisfaction | ||

| I feel fairly satisfied with my present job. | 0.859 | 0.243 |

| Most days I am enthusiastic about my work. | 0.888 | 0.182 |

| Each day of work seems like it will never end. | 0.682 | 0.430 |

| I find real enjoyment in my work. | 0.886 | 0.181 |

| I consider my job rather unpleasant. | 0.789 | 0.303 |

| Variables | (1) |

|---|---|

| Work Values Ethic | |

| Locus of control | 0.088 ** |

| (0.011) |

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| Variables | Job Satisfaction |

| Work values ethic | −0.445 ** |

| (0.128) | |

| Locus of control | −0.027 |

| (0.015) |

| Locus of Control | Job Satisfaction |

|---|---|

| Direct effect | −0.0272 |

| (0.0149) | |

| Indirect effect | −0.0376 ** |

| (0.0106) | |

| Total effect | −0.0648 ** |

| (0.0117) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simmers, C.A.; McMurray, A.J. Navigating Work Career through Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work Values Ethic. Merits 2022, 2, 258-269. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040018

Simmers CA, McMurray AJ. Navigating Work Career through Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work Values Ethic. Merits. 2022; 2(4):258-269. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimmers, Claire A., and Adela J. McMurray. 2022. "Navigating Work Career through Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work Values Ethic" Merits 2, no. 4: 258-269. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040018

APA StyleSimmers, C. A., & McMurray, A. J. (2022). Navigating Work Career through Locus of Control and Job Satisfaction: The Mediation Role of Work Values Ethic. Merits, 2(4), 258-269. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040018