Abstract

This study aims to investigate the relationship between transformational leadership and transactional leadership, as a job resource and contextual performance as a work outcome, mediated by work engagement and moderated by trait mindful awareness as a personal resource. Some researchers highlight work engagement as a mediating mechanism between job resources and individual outcomes, while others suggest that personal resources may improve employees’ awareness of the job resources around them and, in turn, improve their performance. Notably, empirical evidence shows that the moderation of trait mindful awareness is not synergistic, but compensatory, along with the “substitutes for leadership theory.” Data were collected from employees in the United States via the online Amazon Mechanical Turk platform. A total of 282 respondents were randomly assigned to one of two vignettes—one reflecting transformational and one reflecting transactional leadership. The findings revealed that the positive relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance is partially mediated by work engagement. Mindful awareness significantly strengthens the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement. This study contributes to the literature by providing further empirical evidence on the inconclusive contextualization of mindful awareness as a personal resource.

1. Introduction

Researchers and practitioners consistently agree that constructively administering employee performance is crucial for generating positive organizational outcomes. Along with the upheaval of teleworking as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, self-disciplined, motivated acts of employees or their contextual performance have become vitally important. Contextual performance is defined as the behaviors that support the organizational, social, and psychological environment in which the technical core functions [1]. More specifically, it is a form of extra-role behavior that inclines cooperation and following rules, voluntarily participating in additional work responsibilities that are beyond an employee’s formal obligations, and persisting with extra enthusiasm, when necessary, to complete the tasks successfully [2].

Considering the importance of contextual performance, we were motivated to investigate its antecedents. In compliance with a resource-based approach [3], the availability of resources is stated to be vital for improving employee performance in the workplace [4]. Resources can be classified into two types, based on their origins—job and personal resources. Job resources refer to those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reducing job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs and stimulating personal growth and development [5]. On the contrary, personal resources refer to the psychological characteristics or aspects of the self that are generally associated with resilience and the ability to control and impact one’s environment successfully [6].

Among job resources, scholars consistently state that leadership is an essential antecedent of employee outcomes. Different types of leadership style are claimed to have different levels of influence on employee performance [7]. Moreover, among various leadership types, transformational leadership, in particular, is inferred as a contextual structural (i.e., durable) resource that affects performance, because leaders are an integral part of employees’ social context at work [8].

Transformational leadership is defined as the process of building commitment to organizational objectives and then empowering employees to accomplish those objectives [9]. The role of transformational leaders who can motivate their employees to work toward common goals and ensure autonomy to make independent decisions to improve performance, becomes integral, especially so given that the COVID-19 pandemic is reshaping the workplace, inevitably leading many organizations to shift to a work-from-home arrangement. A better understanding of transformational leadership can be reached by contrasting it with transactional leadership. Transactional leadership is usually described as the exchange of valued outcomes between leaders and employees. Transactional leaders are influential in such a way that employees can obtain their best interest and meet their expectations by following what the leaders want them to complete [10]. A transactional leader motivates employees to perform as expected, whereas a transformational leader inspires followers to achieve more than expected [11]. Empirical studies also find positive relationships between transformational leadership and various outcomes; some of these outcomes are proximal, whereas others are distal to the transformational leadership variable. Regarding proximal outcomes, such as job or work engagement, a positive relationship between transformational leadership and job engagement was found in a sample of Spanish employees working in high-tech and knowledge-based small and medium-sized enterprises [12]. This leadership style was also found to be associated with work engagement in a sample of Spanish employees in the tourism sector [13], as well as in a sample of employees in a finance and event management company in Singapore [14]. With respect to distal outcomes such as performance, researchers found a significant positive relationship between transformational leadership and outcomes such as employee performance in a sample of firefighters in the United States [15]. It was also found to be associated with sustainable employee performance among respondents in the construction industry in China [16], task performance and organizational citizenship behavior among employees in the United States [17], task performance in a sample in the United Kingdom [18], task and contextual performance in a sample of frontline employees in five-star hotels in China [19], and contextual performance [20]. In addition, some researchers argue that transformational leadership is more closely associated with contextual performance, while transactional leadership is more closely associated with individual task performance, in which employees perform activities that contribute to the organizational core [20]. Transformational leaders’ tendency to clarify expectations and goals and encourage cooperation, plus their fair and equal treatment, empowerment, and active interaction with their employees create high-quality relationships that can be reciprocated with contextual performance [21].

The mechanism of the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance requires further investigation, as the relationship is distal, rather than proximal [22]. For example, by using metanalytic path modeling, existing research provides evidence on the effect of work engagement on the relationship between distal antecedents (job characteristics, leadership, and dispositional characteristics) and job performance (such as task performance and contextual performance) [23]. In this regard, numerous ways by which transformational leadership can affect contextual performance through individual-level mediators such as psychological safety, self-efficacy, personal identification, and intrinsic motivation, have been proposed [24]. For example, a meta-analysis of 185 independent studies reveals that trust plays a mediating role in the leadership–performance relationship [25]. In addition, an existing study shows that transformational leadership has a positive influence on employees’ proactive work behaviors, in such a way that leadership—at a different hierarchical level—influences the outcome variable via different mediators, such as the employees’ commitment and their confidence to initiate change [26].

The motivational process of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model states that job resources (such as transformational leadership) stimulate work engagement, which in turn enhances positive work outcomes (such as performance) [6]. Work engagement is a positive, fulfilling, and work-related state of mind, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [27]. It should be investigated because it reflects a more comprehensive work-related affective–motivational state encompassing both health-related outcomes—such as affective wellbeing—and motivation-related outcomes, such as intrinsic motivation [28]. In addition, work engagement, which is a form of heavy work investment and reflects an employee’s dedication to the organizational activities, becomes questionable, particularly in times of upheaval caused by a work-from-home approach. Further, a previous empirical study found that teleworking was associated with a lower level of work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic [29].

Likewise, transformational leaders who can empower and inspire employees to take on self-managed responsibilities even if they are not under surveillance seem to be a relevant predictor of their subordinates’ work engagement, particularly during the pandemic period. An existing empirical study also shows the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance among frontline hotel employees [30]. Researchers are also interested in personal resources as boundary conditions of the transformational leadership–contextual performance relationship [31]. In the literature, self-efficacy, organization-based self-esteem, and optimism are found to be common personal resources [32]. Previous researchers indicate that personal resources may act as moderators that govern the way employees realize, formulate, and react to the environment’s goals [33]. In addition, the roles of cognitive processes and individual characteristics in realizing the work environment are supposedly essential factors to consider when predicting work-related individual outcomes [32]. An empirical study indicates that personal resources (e.g., intrinsic work value orientation) can be integrated into the JD-R model in such a way that they strengthen the positive effect of job resources (e.g., job autonomy) on work engagement [34].

Researchers suggest that personal resources such as hope, optimism, and self-efficacy relate to resiliency and the positive core self-concept, whereas mindful awareness is more concerned with how people use their attentional resources to cope with job resources [35,36]. The present study focuses on trait mindful awareness as possessing a higher level of present-moment awareness that enables individuals to allocate their limited attentional resources (i.e., individuals select a limited number of sensory inputs to process while other sensory inputs are neglected) to utilizing available job resources and enhances their ability to deal with and/or deploy the available job resources around them [36,37]. Based on the JD-R model, we assume that employees with a relatively higher level of personal resources—mindful awareness, in particular—are more aware of and open to the full potential of job resources—with the two working together synergistically. However, one existing study discovered the compensating interaction effect of transformational leadership and mindful awareness on intrinsic motivation in the Netherlands [31], which concurs with the “substitutes for leadership” theory [38]. Some researchers argue that mindful awareness can make individuals more resilient to the inadequacy of job resources and cognizant of alternative job resources, considering the ever-changing nature of the work environment [39]. Based on the JD-R model, other researchers state that, as a personal resource, mindful awareness buffers the link between emotional demands and psychological stress [38]. An empirical study provides evidence that mindful awareness significantly strengthened the negative relationship between work pressure and work engagement within its sample [39]. Since the study adopted the narrower scope of intrinsic motivation as an outcome, we should be cautious to avoid simply comparing this compensating moderation with the strengthening moderation. Nevertheless, when it comes to empirical evidence concerning specific personal resources, the literature appears to be inconclusive, and we should further investigate the results empirically.

Based on the argument above, the present study is expected to contribute to the literature by identifying the underlying mechanism (mediation of work engagement) and boundary condition (moderation of mindful awareness) of the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance. The required data were collected online from 282 individuals in the United States via Amazon Mechanical Turk. The respondents were randomly assigned to two vignettes—one reflecting transformational leadership and the other reflecting transactional leadership. The results demonstrated that the positive relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance is partially mediated by work engagement. Moreover, mindful awareness was found to significantly enhance the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement. This study contributes to the literature by providing further empirical evidence on the inconclusive contextualization of mindful awareness as a personal resource, and the inconclusive discussion on the role of personal resources as a boundary condition.

Along with the research scope mentioned above, we reviewed the literature below to justify our hypotheses regarding (1) the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance, mediated by work engagement and (2) the moderating effect of mindful awareness on the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement.

1.1. Relationship of Transformational Leadership and Contextual Performance through Work Engagement

First, we reviewed the literature to justify the proposed main relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance. Existing evidence reveals that transformational leadership has a positive influence on contextual performance. In Western countries, a study found a positive relationship among the employees of a restaurant chain in the United States [40], while another found the same among employees from different companies in Germany [41]. These findings were in agreement with a study on employees from different industries and professional backgrounds in the Netherlands [42]. Evidence has also been collected from Asia, among MBA students from China [43], and among IT professionals in India [44]. Moreover, an existing meta-analysis validates transformational leadership as being positively related to contextual performance [45]. However, as mentioned earlier, the relationship is likely to be distal, so as to understand the mechanism. Some researchers argue that distal antecedents, such as transformational leadership, might influence contextual performance via the mediating mechanism of proximal motivational factors predicting how an individual experiences a desire to self-invest their energy into performing their work at a high level, indicating that work engagement is a promising mediator [23]. Another study shows a positive association between work engagement and contextual performance [46].

Transformational leaders typically communicate clear expectations, manage employees fairly, and identify good performers, thereby encouraging their employees’ work engagement by fostering a sense of attachment to the job [47]. Regarding the relationship between work engagement and contextual performance, both individual and organizational factors affect the psychological experience of work, and this experience may lead to certain work behaviors [48]. Some studies also empirically confirm the mediating role of work engagement; a meta-analysis confirms the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance [23]. More recent studies provide evidence of the above-mentioned relationship in a sample of 195 project team members in 39 teams from different contractors in Malaysia [49]. Furthermore, in a sample of Taiwanese hospital staff, it was found that work engagement mediates the positive relationship between transformational leadership and helping behaviors that are considered to cover an aspect of contextual performance [50].

The studies mentioned above aimed to investigate the effect of transformational leadership. One important issue to be clarified is what the expression “low in transformational leadership” means in these studies. The issue stems from the fact that “low in transformational leadership” may not mean a specific type of leadership. Some respondents, as well as some researchers, are more likely to expect laissez-faire leadership, while others may expect transactional leadership, as it is perceived to be a contrasting type of leadership, which makes the discussion confusing. To pose a clearer argument, a “baseline” should be established. For this purpose, transactional leadership is appropriate as the baseline, because it is similar to transformational leadership in its necessity of deliberate intention for implementation, compared to laissez-faire leadership. In fact, both transformational and transactional leaders actively dedicate their time and effort and attempt to inhibit problems, which is in direct contradiction to the extremely passive laissez-faire leaders who avoid decision making and supervisory responsibilities [11]. A previous study used transactional leadership vignettes as a baseline to analyze the “effect of transformational leadership”, although they called the baseline vignette “non-transformational” [51]. In line with the above argument, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1.

The positive relationship between transformational leadership, in contrast to transactional leadership, and contextual performance is mediated by work engagement.

1.2. Moderation of Mindful Awareness

Next, we focused on a potential contingency for a part of the main relationship; that is, between transformational leadership and contextual performance. Specifically, the above-mentioned mediated relationship is likely to be contingent. Some researchers propose that transformational leadership affects work engagement to various degrees, and under different conditions [52]. As previously mentioned, existing research investigated the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance via work engagement. However, little attention has been paid to the conditional effect of mindful awareness on the indirect positive relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance through work engagement, acting as a mediator with a comprehensive perspective.

As mentioned in Section 1, studies on the role of mindful awareness as a boundary condition in the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance were inconclusive. As extensively discussed earlier, the JD-R model suggests positive moderation or a strengthening effect of personal resources on the relationship between job resources and work engagement [6]. Although they are not specifically defined as mindful awareness, other personal resources have been found to offer positive moderation [34]. In contrast, some researchers argue that mindfulness can act as a substitute for low levels of transformational leadership in enhancing intrinsic motivation and, in turn, extra-role behavior (equivalent to contextual performance) [31].

Considering the inconclusiveness of the theoretical discussion and empirical findings, a solution may exist in the moderation’s boundary condition. Accordingly, to set the sign condition of our moderation hypothesis, we focused on the cultural differences between the previous study conducted in the Netherlands [31] and our study in the United States. More specifically, we address the two countries’ cultural differences in masculinity and long-term orientation, according to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [53]. We propose that people from the Netherlands, who present low masculinity and a high long-term orientation, may be more likely to consider the team’s long-term maintenance and development from a mutual cooperation perspective. Therefore, those who have higher mindful awareness and can thus be transformative by themselves tend to motivate themselves to compensate for the lack of transformational leadership. In contrast, people in the United States, who are characterized by high masculinity and low long-term orientation, may be more likely to value straightforward recognition from their leaders with relatively short-term-oriented decisions. Hence, those with higher mindful awareness tend to enhance their own transformative nature under a higher level of transformational leadership. Therefore, we set our second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

Mindful awareness moderates the indirect effect of transformational leadership on contextual performance through work engagement; the higher the level of mindful awareness, the stronger the effect.

1.3. Conceptual Framework

With the two hypotheses developed above, a conceptual framework was developed, as shown in Figure 1. As transformational leadership would be interrogated by the hypothetical vignettes, the variable was described in a box. Other variables are expected to be latent.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

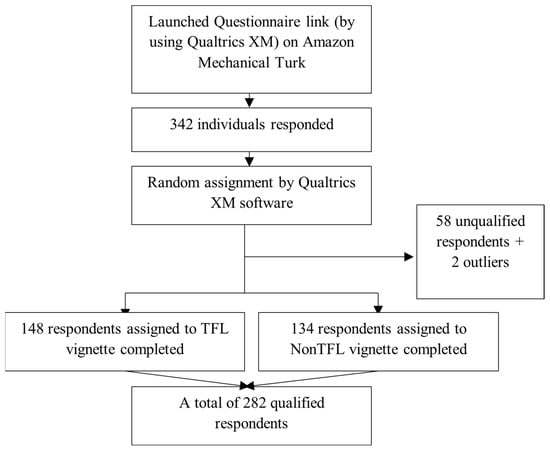

To test the hypotheses, an online survey was conducted with the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform, “an increasingly popular source of experimental participants due to its convenience and low cost (relative to traditional laboratories)”, although it “presents challenges related to statistical power and reliability” [54]. A total of 342 individuals responded using the Qualtrics XM survey software. Among them, 58 and 2 respondents were found to be unqualified and outliers, respectively, after a studentized residuals analysis was performed. After removing these participants, 282 respondents with 40-plus working hours in the United States were finally selected for analysis. Due to this data collection approach, we could not access the information of non-participants who registered for the platform and met our criteria. Instead, we assessed the late response bias and found that the early and late participants were not statistically different in terms of gender, age, or educational background. Independent sample t-tests were used for age (t (140) = 1.02, p > 0.05) and education (t (140) = –0.30, p > 0.05), while a chi-squared test was used for gender (χ2 (1) = 1.26, p > 0.05); the results showed that there was no major late response bias. The study design was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which participants were randomly assigned (by the Qualtrics XM software) to two different vignettes, one on transformational leadership, and the other on transactional leadership (Appendix A). The two different vignettes were constructed based on items of transformational and transactional leadership from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ)’s 28-item scale [55]. In compliance with the developer’s request, the items of the MLQ may not be published. Instead, the factor level information is provided in Appendix B.1. The overall procedure, including sampling, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process of research.

2.2. Measures

For the main analysis, we used the transformational versus transactional leadership vignettes (Appendix A), as well as the established scales to measure mindful awareness, work engagement, and contextual performance. Moreover, for the purpose of confirming manipulation by the vignettes, another established scale to measure transformational leadership was adopted.

Regarding the intervention, transformational versus transactional leadership was coded based on the assigned vignette—1 for the former and 0 for the latter.

Mindful awareness was measured using the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS)’s 10-item scale of awareness (Appendix B.2) [56]. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from never (0) to always (4). Example items were “I am aware of what thoughts are passing through my mind” and “When talking with other people, I am aware of the emotions I am experiencing”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80, indicating good reliability.

Work engagement was measured using a 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Appendix B.3) [28]. Items were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from never (0) to always (6). Example items included “At my work, I feel bursting with energy” and “I am enthusiastic about my job”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.97.

Contextual performance was measured using a 12-item scale (Appendix B.4) [57]. Items were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from seldom (1) to always (5). Example items were “I take on extra responsibilities” and “I actively participate in work meetings”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.97.

For the manipulation check, the respondent’s perceived transformational leadership for the assigned vignette was measured using the MLQ’s 20-item scale regarding transformational leadership [55]. We excluded the eight items regarding transactional leadership that were used to make the respective vignette, as our purpose here was to measure the perceived transformational leadership based on each vignette. Items were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from not at all (0) to frequently (4). Example items included “The leader talks optimistically about the future” and “The leader spends time teaching and coaching”. Transformational leadership had an acceptable reliability coefficient, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98.

Each scale has been utilized previously by researchers and they represent established methods of measurement that have been confirmed as reliable and valid.

2.3. Analysis

We first reviewed the descriptive statistics, including demographic data of the respondents and means, standard deviation (SD), and correlations among variables. Second, the manipulation check was carried out with an independent sample t-test, to confirm if our intervention was successful. Third, the hypotheses were tested, and some additional analytical results were found. More specifically, a conditional process analysis [58] was conducted to test the path model, which comprises mediation (H1) and moderated mediations (H2). The conditional indirect effect was analyzed with Model 7 in the Process Macro of IBM SPSS 27. Conditional process analysis has the advantage of analyzing the moderated mediation process as a whole, although we should also be cautious to argue the effect of a mediator on an outcome as the mediator does not intervene. Lastly, simple slope analyses were performed regarding the hypothesized moderation of mindful awareness and that of demographic characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The demographic data are shown in Table 1, while mean, SDs, and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 2. Table 2 shows that transformational leadership and work engagement are associated with contextual performance. The results revealed no association between mindful awareness and transformational leadership.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviation, and correlations.

3.2. Manipulation Check

Before conducting the main analysis, we needed to confirm that our intervention through the hypothetical vignettes was successful. For this purpose, we implemented a manipulation check. The authors created the transformational and transactional leadership vignettes (Appendix A) for this study, based on the MLQ items [55]. As a preliminary check, an independent sample t-test was conducted by comparing the transformational vignette and transactional vignette groups in terms of participants’ perception of the level of transformational leadership utilizing the original 20-item MLQ. A significant difference was noted in the mean scores of MLQ between the respondents reading the two different vignettes (Table 3), in that respondents perceived a stronger transformational leadership behavior in the transformational leadership vignette than that on transactional leadership.

Table 3.

Independent sample t-test for manipulation check.

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

Because of the successful manipulation, we could proceed to the main analysis for hypothesis testing. Table 4, showing the main analysis results, delineates the findings of the process analysis for (1) the mediating effect of work engagement on the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance and (2) the moderating effect of mindful awareness on the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement.

Table 4.

Conditional direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on contextual performance mediated my work engagement and moderated by mindful awareness.

Transformational leadership was related to work engagement as indicated by a significant unstandardized regression coefficient (B = 1.92, p < 0.001). Work engagement was significantly related to contextual performance (B = 0.57, p < 0.001), as transformational leadership was (B = 0.27, p < 0.01), indicating that work engagement partially mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance. Hypothesis 1 was thus supported.

The interaction term of transformational leadership and mindful awareness was significantly related to work engagement (B = 0.96, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. The index of moderated mediation was 0.79, with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals [0.26, 0.83], suggesting that the strength of the hypothesized indirect effect is conditional on the value of the moderator, mindful awareness.

Model 1 explained a significant proportion of variance in work engagement (R2 = 0.48, p < 0.001). Similarly, Model 2 explained a significant proportion of variance in contextual performance (R2 = 0.73, p < 0.001). The variance inflation factor values for the variables in the two models fall within the acceptable limits (less than 2.5) and indicate no serious multicollinearity problems [59].

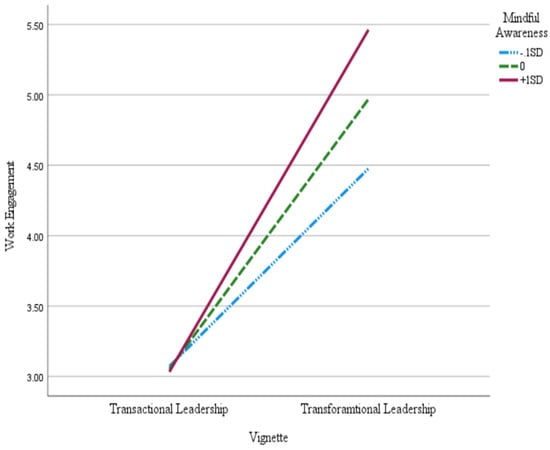

To assess whether the interaction term followed the hypothesized pattern, a simple slope analysis was performed at one SD above and below the mean of the mindful awareness measure. Figure 3 illustrates the conditional effect of mindful awareness on the relationship between the two different leadership vignettes and work engagement: the higher the mindful awareness, the stronger the main relationship.

Figure 3.

Moderation of mindful awareness on the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement. +1SD = one standard deviation above the mean; −1SD = one standard deviation below the mean.

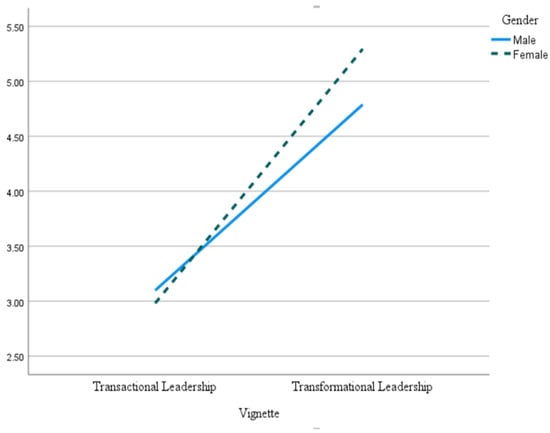

In addition, among the demographic variables of the current study, gender was found to moderate the relationship between the intervention variable and work engagement, as shown in Figure 4 (B = 0.62, p < 0.05, male = 1, female = 2). The result shows that female respondents were more sensitive to the availability of transformational leadership.

Figure 4.

Moderation of gender on the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation

We now discuss the results and their relationship with the theoretical foundations of the study, and provide our interpretation of unexpected results.

Based on the results, both hypotheses were supported; thus, the theoretical foundations for the two hypotheses—the JD-R model for the mediation of work engagement and the moderation of mindful awareness—were applicable to our sample from the United States.

Regarding Hypothesis 2, we found the literature to be inconclusive, thus requiring further examination. Mindful awareness is a valuable personal resource to help employees become cognizant of the existing social aspect of contextual resources, such as the instances of transformational leadership around them [60]. Such open awareness contributes to a psychological connection with their work and performance. Consistent with this definition, the findings revealed that a higher level of mindful awareness strengthens the indirect positive relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance via work engagement. More specifically, according to the simple slope analysis results (Figure 3), among the transactional leadership vignette respondents, work engagement appeared fairly similar at the three levels of mindful awareness. In contrast, for the transformational leadership respondents, work engagement was considerably different at different levels. Overall, mindful awareness did not predict work engagement statistically, as shown in Table 4 (B = −0.04, p > 0.05), although some researchers find that personal resources are directly related to work engagement [31]. One possible explanation is that mindful awareness is not activated when facing transactional leadership; therefore, one does not improve their work engagement in this case. We can argue that mindful awareness is considered the antecedent of typical personal resources such as self-efficacy, organizational-based self-esteem and optimism, and that the activation process is necessary to link mindful awareness to the personal resources that are, in turn, related to work engagement.

In addition, the result shows that female respondents were more reactive to the availability of transformational leadership. This result is, to some extent, in line with a previous study which shows that female employees are predicted to show a higher effect of trait-based authentic leadership (which originated from process- or behavior-based transformational leadership) when compared to male employees [61,62]. Female employees, unlike their male counterparts, are more likely to play a care-giving role in their family contexts, and thereby are more prone to quick resource depletion. Consequently, they may appreciate the positive support they receive from transformational leaders (who can capture employees’ trust, faith, respect, and appreciation) better than their male counterparts. This constitutes a possible reason for their increased sensitivity to the availability of transformational leadership observed in the current study.

4.2. Practical Implications

Our results provide some notable practical implications. First, based on the significantly positive effect of transformational leadership on contextual performance, organizations should enhance such leadership among current managers and prioritize the recruitment and selection of individuals with transformational leadership tendencies, especially for managerial positions, to promote employees’ contextual performance. Second, the finding that mindful awareness strengthens the effect of transformational leadership on work engagement can imply that organizations should recruit employees with high mindful awareness, so that managers as transformational leaders can more effectively enhance work engagement and, in turn, contextual employee performance. Moreover, especially for those with higher mindful awareness, organizations should emphasize developing their managers’ transformational leadership to enhance employees’ work engagement.

Additionally, to cope with issues such as quiet quitting that emerged along with the unprecedented changes in workplace contexts since the COVID-19 pandemic, recruiting and maintaining transformational leaders is also vital, as quiet quitting is less about employees and rather more about the leadership that shapes the particular nature of the relationship with those employees [63].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study successfully provides empirical evidence on the effect of transformational leadership (as a contextual resource) on contextual performance, mediated by work engagement and moderated by mindful awareness (as a personal resource), certain limitations should be noted.

First, although we conducted an RCT and used transformational and transactional leadership to obtain the experimental data, the mediator (work engagement) was not randomly assigned; therefore, we cannot argue for the effect of work engagement convincingly. A causal mediation analysis can validate the causal effect of work engagement on contextual performance [64]. Second, a generalization issue exists. Due to the convenience sampling method applied, our participants did not represent the whole population but only the Amazon Mechanical Turk registrants who work 40 plus hours per week in the United States. Thus, the present study should be regarded as a “case study” of a specific sample. Random sampling is the solution; however, we need to find a different source of survey respondents, as Amazon Mechanical Turk is not sufficient due to its restrictions in terms of the survey process. Moreover, future studies could replicate this model in other countries and cultures (with sufficient external validity) and generalize the argument beyond the United States.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between transformational leadership as a job resource and contextual performance as a work outcome, mediated by work engagement and moderated by trait mindful awareness; specifically, we examined one of its dimensions, mindful awareness, as a personal resource. Theoretically, both the mediation and moderation are based on the JD-R model.

We analyzed the conditionally mediated relationship using RCT. As predicted, the findings revealed that the positive relationship between transformational leadership and contextual performance is partially mediated by work engagement (B = 1.92, p < 0.001 between transformational leadership and work engagement; B = 0.57, p < 0.001 between work engagement and contextual performance; B = 0.27, p < 0.01 between transformational leadership and contextual performance, directly). Moreover, we found that mindful awareness significantly strengthens the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement (B = 0.96, p < 0.001).

This study contributes to the literature by providing further empirical evidence on the inconclusive contextualization of mindful awareness as a personal resource in the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement. Concerning practical implications, organizations should enhance such leadership among current managers and emphasize the recruitment and selection of individuals with transformational leadership tendencies to cope with issues such as quiet quitting in times of upheaval. Moreover, organizations should also consider recruiting and maintaining employees with higher levels of mindful awareness so that employees can handle the unfavorable working conditions by utilizing their own personal resources of mindful awareness, and without relying too heavily on the availability of job resources around them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.Z. and Y.T.; methodology P.P.Z. and Y.T.; software, Y.T.; validation, P.P.Z. and Y.T.; formal analysis, P.P.Z.; investigation, P.P.Z.; resources, P.P.Z. and Y.T.; data curation, P.P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.T.; visualization, P.P.Z.; supervision, Y.T.; project administration, P.P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the complete anonymity of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Transformational Leadership Vignette

Mr. Smith is your department manager. He is a man of dedication, conscientiousness, and optimism. Promoting positive values and maintaining professional standards of behaviors in an ethically appropriate manner are essentially his norms. In addition, he possesses the skill, energy, and self-confidence to guide and facilitate efforts for change in the department. Additionally, Mr. Smith is a well-known trouble-shooter in the organization, retrieving, translating, and utilizing data to solve impending problems.

He typically clearly communicates expectations to his team members and expresses his commitment to goals and shared visions. Further, he emphasizes the importance of teamwork. When necessary, he offers further guidance and support to the team members (including you) in achieving their full potential while accomplishing organizational goals. He is also good at motivating his team members by introducing meaningful challenges in their assigned tasks, driving everyone towards a satisfying and rewarding future. Mr. Smith encourages his team to seek new and creative approaches to problems and refrains from criticizing a team member’s ideas, especially when they differ from his. Most importantly, he deliberately communicates his trust in his team members’ ability to attain targets. In addition, Mr. Smith is an active listener. He usually attempts to pay attention to understand the need of each team member. He assigns tasks to the team members as a means of developing them per their differences.

Appendix A.2. Transactional Leadership Vignette

Mr. Smith is your department manager. He emphasizes order and structure and is a man of discipline. However, his strict and rigid standards may discourage the creative problem-solving skills of team members (including you). He is inherently resistant to change and unwilling to take proactive actions to counteract possible obstacles as he lacks the insight to foresee them. It seems like his emphasis is on maintaining the status quo—a well-organized and structured working environment—and keeping the ship afloat. Even though he is good at handling routine, he usually becomes incompetent to cope with issues requiring creative solutions. He prefers to work within the existing systems and limitations and attempts to function within the boundaries to reach targets.

He usually informs his team members that their performance will be evaluated monthly. He intends to elicit the desired performance from team members through rewards and punishments. Particularly, he tends to reward or criticize team members individually, without very much emphasis on teamwork. One of his priorities is to ensure that predetermined criteria and guidelines are met accurately. He refrains from interfering with the workflow unless an issue arises. Rather, Mr. Smith focuses on closely monitoring loopholes, errors, and deviations from standards and taking corrective actions.

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) [55]

0 = Not at all, 1 = Once in a while, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = fairly often, 4 = Frequently, if not often

Sub-scale names–

1. Transformational leadership (20 items totally): 1.1 Idealized attributes (4 items), 1.2 Idealized behaviors (4 items), 1.3 Inspirational motivation (4 items), 1.4 Intellectual stimulation (4 items), 1.5 Individual consideration (4 items)

2. Transactional leadership (8 items totally): 2.1 Contingent reward (4 items), 2.2 Management-by-exception (active) (4 items)

Appendix B.2. Mindful Awareness from the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS) [56]

1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often, 5 = Very often.

1. I’m aware of what thoughts are passing through my mind.

2. When talking with other people, I am aware of their facial and body expressions.

3. When I shower, I am aware of how the water is running over my body.

4. When I am startled, I notice what is going on inside my body.

5. When I walk outside, I am aware of the smells and how the air feels against my face.

6. When someone asks how I am feeling, I can identify my emotions easily.

7. I am aware of thoughts I’m having when my mood changes.

8. I notice changes inside my body, like my heart beating faster or my muscles getting tense.

9. Whenever my emotions change, I am conscious of them immediately.

10. When talking with other people, I am aware of the emotions I am experiencing.

Appendix B.3. Work Engagement [Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9)] [28]

0 = Never, 1 = Almost never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often, 5 = Very often, 6 = Always

1. At my work, I would feel bursting with energy.

2. At my job, I feel strong and vigorous.

3. I am enthusiastic about my job.

4. My job inspires me.

5. I feel like going to work when I get up in the morning.

6. I feel happy when I am working intensely.

7. I’m proud of the work that I do.

8. I am immersed in my work.

9. I get carried away when I am working.

Appendix B.4. Contextual Performance [57]

1 = Seldom, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = Often, 5 = Always.

1. I take on extra responsibilities.

2. I start new tasks myself when my old ones were finished.

3. I take on challenging work tasks when available.

4. I work at keeping my job knowledge up to date.

5. I work at keeping my job skills up to date.

6. I come up with creative solutions to new problems.

7. I keep looking for new challenges in my job.

8. I do more than was expected of me.

9. I actively participate in work meetings.

10. I actively look for ways to improve my performance at work.

11. I grasp opportunities when they present themselves.

12. I know how to solve difficult situations and setbacks quickly.

References

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Borman, W., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.S.; Chiang, H.H.; McConville, D.; Chiang, C.-L. A longitudinal investigation of person–organization fit, person–job fit, and contextual performance: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Anwar, S.; Haider, N. Effect of leadership style on employee performance. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, K.; Sacramento, C.A.; Binnewies, C. Transformational leadership and burnout: The role of thriving and followers’ openness to experience. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert, K.W.; Lewis, P. Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/developmental analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Van Muijen, J.J.; Koopman, P.L. Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Vázquez, G.; Castro-Casal, C.; Álvarez-Pérez, D.; Río-Araújo, D. Promoting the sustainability of organizations: Contribution of transformational leadership to job engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, A.M.; Vázquez, J.P.A.; Faíña, J.A. Transformational leadership and work engagement: Exploring the mediating role of structural empowerment. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.; Ayoko, O.B. Employees’ self-determined motivation, transformational leadership and work engagement. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, M.T. Leadership in extreme contexts: Transformational leadership, performance beyond expectations? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 23, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, X.; Ni, J. The impact of transformational leadership on employee sustainable performance: The mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.Z.; Armenakis, A.A.; Feild, H.S.; Mossholder, K.W. Transformational leadership, relationship quality, and employee performance during continuous incremental organizational change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 942–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.; Clarke, S.; O’Connor, E. Contextualizing leadership: Transformational leadership and Management-By-Exception-Active in safety-critical contexts. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hua, N. Transformational leadership, proactive personality and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Shao, J. Feminine traits improve transformational leadership advantage: Investigation of leaders’ gender traits, sex and their joint impacts on employee contextual performance. Gend. Manag. 2022, 37, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Oh, I.-S.; Courtright, S.H.; Colbert, A.E. Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 223–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J.; Shamir, B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, R.R.; Zvi, H.A. Managing contextual performance. In Performance Management: Putting Research into Action; Smither, J.W., London, M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 297–328. [Google Scholar]

- Legood, A.; van der Werff, L.; Lee, A.; Den Hartog, D. A meta-analysis of the role of trust in the leadership-performance relationship. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Griffin, M.A.; Rafferty, A.E. Proactivity directed toward the team and organization: The role of leadership, commitment and role-breadth self-efficacy. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Lamarche, A. Teleworking, Work Engagement, and Intention to Quit during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Same Storm, Different Boats? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, B.; van Woerkom, M.; Menting, C. Mindfulness as substitute for transformational leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Fischbach, A. Work engagement among employees facing emotional demands: The role of personal resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Smulders, P.; De Witte, H. Does an intrinsic work value orientation strengthen the impact of job resources? A perspective from the Job Demands–Resources Model. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. A diary study on the happy worker: How job resources relate to positive emotions and personal resources. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 21, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.L.; Teo, S.T.; Pick, D.; Roche, M. Mindfulness as a personal resource to reduce work stress in the job demands-resources model. Stress Health 2017, 33, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahn, B.; König, P. Is Attentional Resource Allocation Across Sensory Modalities Task-Dependent? Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 2017, 13, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, S.; Jermier, J.M. Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1978, 22, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Van Strydonck, I.; Decuypere, A.; Decramer, A.; Audenaert, M. How to foster nurses’ well-being and performance in the face of work pressure? The role of mindfulness as personal resource. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 3495–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, J.; Nelson, N.E.; Allen, T.D.; Xu, X. Leadership predictors of innovation and task performance: Subordinates’ self-esteem and self-presentation as moderators. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 465–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. Work engagement and Machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. Leadership. Q. 2010, 21, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Jena, L.K.; Bhattacharyya, P. Transformational leadership and contextual performance: Role of integrity among Indian IT professionals. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 6, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Smith, T.A.; Wang, J.; Zimmerman, R.D. Relative importance of leader influences for subordinates’ proactive behaviors, prosocial behaviors, and task performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C.; Kooij, D.; Kroon, B.; de Reuver, R.; van Woerkom, M. Organizational support for strengths use, work engagement, and extra-role performance: The moderating role of age. J. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 15, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W.H.; Schneider, B. The meaning of employee engagement. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokory, S.M.; Suradi, N.R.M. Transformational Leadership and its impact on extra-role performance of project team members: The mediating role of work engagement. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.Y.; Tang, H.C.; Lu, S.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Lin, C.C. Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovjanic, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Jonas, K. Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S.L.; Leiter, M.P. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Ork Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, J.W. Improving the statistical power and reliability of research using Amazon Mechanical Turk. Account. Horiz. 2021, 35, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ)—Tests, Training. Available online: https://www.mindgarden.com/16-multifactor-leadership-questionnaire (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Cardaciotto, L.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Moitra, E.; Farrow, V. The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment 2008, 15, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; Van Buuren, S.; Van der Beek, A.J.; De Vet, H.C. Improving the individual work performance questionnaire using rasch analysis. J. Appl. Meas. 2014, 15, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed.; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, O., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Date Analysis with Readings; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliff, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, B.; Menting, C.; van Woerkom, M. Why mindfulness sustains performance: The role of personal and job resources. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraba, D.; Wirawan, H.; Salam, R.; Faisal, M. Working from home during the corona pandemic: Investigating the role of authentic leadership, psychological capital, and gender on employee performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1885573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, T.H. Authentic versus transformational leadership: Assessing their effectiveness on organizational citizenship behavior of followers. Int. J. Bus. Public Adm. 2013, 10, 40–61. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A335188936/AONE?u=anon~65599d68&sid=googleScholar&xid=bd0639ca (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/08/quiet-quitting-is-about-bad-bosses-not-bad-employees?utm_campaign=hbr&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Imai, K.; Keele, L.; Tingley, D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).