1. Introduction

The quality of medical care considers the outcomes of organized healthcare systems and actions aimed at improving the health and well-being of patients [

1]. The quality of medical care provided to patients comprises vast phenomena; consequently, it is impacted by multilevel factors of influence [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The rise in demand for healthcare quality coupled with advances in clinical practice and the associated costs has led to concerns over the validity and reliability of satisfaction as a stand-alone measurement of clinical practice [

6]. The current COVID-19 pandemic context further stresses this demand through the assessment of present [

7] and future quality of care [

8]. In particular, due to the critical demand to maximize patient care in a short time span [

8]. Accordingly, while the focus on quality of provided medical care has shifted from costs and activity towards the importance of the resources, evidence shows that individual- and organizational-level factors impact healthcare workers’ delivery of quality of care. Healthcare professionals’ self-assessments and perceptions of quality of care are strong indicators of such outcomes [

4,

9]. Thus, the quality of medical care provided to patients is influenced by healthcare workers’ attitudes and work situations [

4,

10,

11]. The quality of provided care grounded in the work environment has an organizational level of control that can be improved by addressing specific characteristics such as staffing [

12,

13], organizational preparedness [

14,

15], and leadership [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Similarly, individual-level characteristics can also lead to the improvement of the quality of provided care [

20,

21]. Therefore, evidence shows that an understanding of social networks in healthcare environments is of importance to understanding social aspects contributing to improved quality of care [

22,

23,

24].

The recent healthcare literature addresses such impacts, detailing the importance of poor perceptions of social support hindering professional outcomes among healthcare workers at the individual level [

24,

25]. Nevertheless, such characteristics are often assessed individually or categorically [

20]. This operationalization presents a research gap towards the exploration of such individual characteristics in combination with organizational structures and processes leading to quality of care. Similarly, while leadership is related to outcomes of improved quality of care provided to patients [

18], the impact of specific leadership types on quality of care remains unexplored. Such is the case of ethical leadership [

18,

26], whose concept is being challenged in the healthcare context [

26]. On the other hand, knowledge management initiatives have aimed to improve perceptions of quality of care by stimulating knowledge mobilization among healthcare professionals and patients [

15]. Knowledge management frameworks, while still a “positive deviance” inside healthcare organizations [

27], rely on similar social and organizational structures to improve the quality of care [

14].

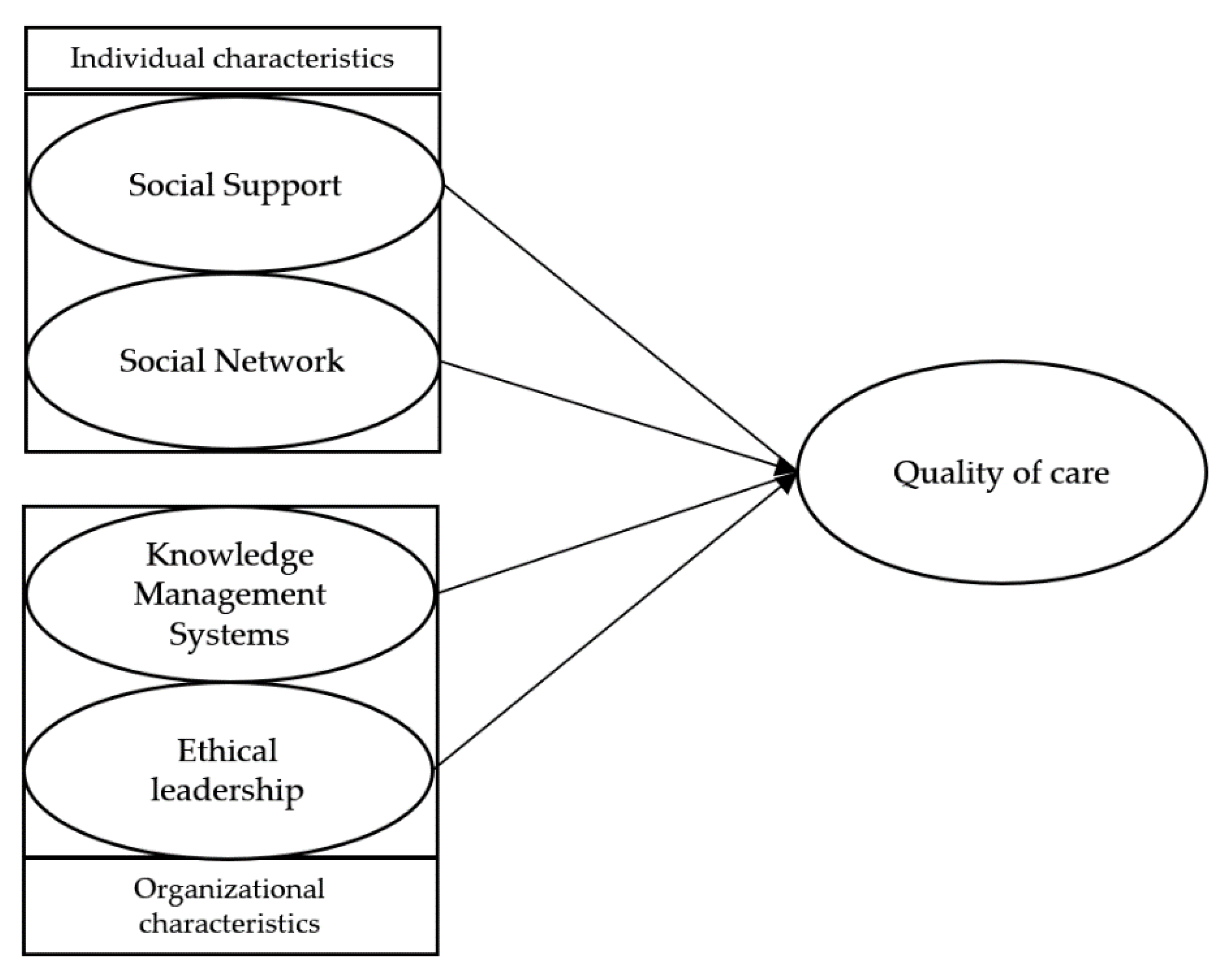

To address this gap, our research shifts quality of care assessment from the patient’s perspective to a healthcare professional’s self-assessment perspective. Specifically, our research aims to understand the impact of the perceptions of quality in social support, the presence of robust social networks (as individual characteristics), the healthcare professionals’ awareness of ethical leadership, and the existence of knowledge management systems (as organizational characteristics) in healthcare professionals’ perception of the quality of care provided to patients. We used a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to provide a three-fold contribution. First, to assess quality of care under a complex causal configuration approach, we analyzed the relationship between individual and organization characteristics in a nonlinear fashion. Second, to understand such characteristics’ impacts on quality of care, we shifted patient assessment towards healthcare workers’ self-assessment. Third, we offer insights into work-based strategies to advance professional outcomes in the context of healthcare workers’ management.

5. Discussion

The results show that all studied conditions are core conditions for both solutions leading to the presence and absence of quality care. This is consistent with the intricate interdependencies surrounding the delivery of the best possible medical care to patients [

38] and its complex relationship with healthcare workers’ attitudes and work environments [

4,

10,

11]. Regarding causal configurations, the results show five configurations leading to the presence of quality of care (qcare). A strong perception of social support among peers (support) is present in four of the configurations in a complex relationship with the other conditions. Such results stress the importance of fostering a peer support culture among healthcare workers, given the evidence surrounding the improvement of medical outcomes when distinct facets of peer support and engagement are assessed in the context of social networks [

20,

23]. The social network condition, on the other hand, while only being present in two of the configurations leading to qcare (Conf 4, 5—

Table 6), stressing the importance of robust social networks, regardless of their category, as an important condition leading to qcare [

20,

22,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. On the other hand, the presence of awareness of knowledge management systems and ethical leadership can contribute to qcare even when social support is absent (Conf 1—

Table 6). Therefore, in circumstances when the quality of social support by peers is deemed poor, an awareness of existing knowledge management systems paired with ethically perceived leaders among healthcare workers still supports the delivery of good qcare. Such results follow the importance given by healthcare workers to knowledge dissemination and development in achieving better collaboration, support, and innovation [

58]. Additionally, ethical leaders serve as role models whose appropriate behavior is deemed as acceptable and worth following. Such appropriate behavior can be converted to new and improved standards [

39,

41], and therefore, supporting qcare. Two configurations (Conf 2, and 4—

Table 6) show that even in the case of the absence of ethical leadership there is still a possibility to offer qcare. Nevertheless, while ethical leadership is absent, both configurations show the presence of either social support and robust social networks, or social support and awareness of knowledge management systems. Such result suggests that, even in circumstances where ethical leadership is absent, healthcare workers can still be driven towards providing qcare if relationships among peers are valued or informal communications sustain the organization. We propose that the need to maintain ethical behaviours under new and constant demands can shift from leaders to peers when perceptions of ethical leadership are absent. That is, that the standard of ethical behavior is diverted towards work peers through the development of social norms grounded on caring and support for one another in such circumstances. Two configurations stress the importance of the individual characteristics leading to the presence of qcare (Conf 4, 5—

Table 6). In the two configurations, organizational factors remained irrelevant or even absent from the configuration. Such findings seem to explain the quasi-accidental nature of knowledge flow in healthcare settings if communication channels are available and fostered [

49]. Similarly, the absence of knowledge management systems inside the healthcare organization can still lead to the presence of qcare (both in Conf 3, 5—

Table 6) This further underpins the professional importance given by healthcare workers to communication and information flows [

49,

58], even in circumstances where formal systems of knowledge management are not recognized or identified. The five configurations in

Table 6 lead to the presence of qcare, each one involving a combination of three conditions and thus suggesting that the presence of qcare is demanding in this healthcare setting.

Regarding the causal configurations leading to the absence of qcare (~qcare) three configurations are presented. There were fewer configurations leading to ~qcare (three) than to qcare (five). Nevertheless, each configuration requires only the combination of two conditions (specifically, their absences), thus making the combinations leading to the absence of quality of care easier to achieve than the ones leading to qcare. This contrasts with the larger number of configurations leading to qcare (five) and further corroborates the complex and interdependence nature of characteristics leading to qcare [

38]. Results also show that only the absence of the conditions is related to ~qcare. One of the configurations (Conf 1—

Table 7) shows that the absence of ethical leadership paired with the absence of robust social networks led to ~qcare. Such a result in this context inversely corroborates evidence coming from previous research. Ethical leaders can foster collaboration and innovation while ensuring channels of communication [

44]. Nevertheless, evidence shows that an absence of identifiable leadership, compounded by communication issues, can lead to a shortage of social networks, exacerbating professional isolation [

21], thus compromising qcare provided to patients. Equally, the absence of ethical leadership is also paired with the absence of quality of social support as conditions leading to ~qcare in one configuration (Conf 2—

Table 7). This further corroborates evidence presenting connections between ethical leadership and a sense of social support. The absence of ethically perceived leaders is related to reduced collaboration and accountability [

44], leading to ~qcare.

The last configuration (Conf 3—

Table 7) shows that the absence of knowledge management systems, when paired with the absence of quality of social support, led to ~qcare. This result also inversely corroborated previous research in the healthcare context. Knowledge management systems, while contributing to medical care and performance, rely heavily on communication to be successful [

27]. In particular, knowledge management activities can promote qcare, especially when combined with personnel engagement in a flexible manner [

56]. Similarly, in circumstances where both knowledge management systems and social support among peers are absent, so will be the perception of qcare provided to patients.

Results also show asymmetry with similar configurations for the solution of presence and absence of quality of care. Nevertheless, while some configurations leading to the qcare only combined individual (Conf 4, 5—

Table 6) or organizational conditions (Conf 1—

Table 6), all the configurations leading to ~qcare combined both (

Table 7). This insight shows that, while easier to achieve, absence of quality of care combines the absence of both individual and organizational characteristics. As such, strategies focused on countering ~qcare should further focus on interdependence [

38], and account for the more diluted, less focused circumstances leading to such outcome.

Our findings provide insight for the research questions, given the solutions found in

Table 5.

RQ1: Robust social networks contribute to qcare in several ways. Robust social networks are present in two configurations leading to quality of care (Conf 4, and 5—

Table 6) and it is found combined in circumstances where the absence of organizational conditions took place. Such results suggest parallels to the complex, multilevel impacts of strong social networks that might counter a lack of awareness of organizational systems and leadership roles through the quality and frequency of communication flows.

RQ2: Social support in the workplace contributes to qcare in several ways. It is found in four out of the five configurations leading to qcare. Social support in the workplace is absent in one configuration leading to the presence of quality care, results show that its absence is also found in two of the three configurations leading to ~qcare. As such, social support in the workplace is a major contributor to qcare in this university hospital environment. Consequently, it should be included in the development of strategies aimed at maximizing such an outcome.

RQ3: Ethical leadership contributes to quality of care in several ways. As a condition, its presence is relevant for two configurations leading to the presence of quality of care (Conf 1, and 3—

Table 6). Results show that circumstances where the presence of ethical leadership is combined with social support could lead to the presence of quality of care if the awareness of knowledge management systems is absent (Conf 3—

Table 6). Similarly, the presence of ethical leadership is also found in one solution leading to the presence of quality of care when an awareness of knowledge management systems is present, but the quality of social support is absent (Conf 1—

Table 6). This combination with individual characteristics contributes to further configurations leading to the absence of quality of care (Conf 1, and 2—

Table 7). This balanced role of ethical leadership allows for an exploration of flexible strategies when promoting quality of care in the university hospital, allowing for individual or mixed levels of intervention. Furthermore, such results further underpin the pivotal nature of ethical leaders in the context of healthcare. Such a leadership style is commonly linked to quality of care given the articulation of organizational structures with collaboration and innovation behaviours [

26].

RQ4: The awareness of knowledge management systems contributes to quality of care in several ways. While related to the presence of quality of care (Conf 1 and 2—

Table 6), an awareness of knowledge management systems is also absent in certain configurations leading to the outcome (Conf 3, and 5—

Table 6). Similar to the absence of ethical leadership configurations, the absence of awareness of knowledge management systems at the university hospital can still lead to the presence of quality of care if robust social networks, capable of strong social support, and ethical leaders were present. Nevertheless, healthcare workers perceive, rely on, and intrinsically acknowledge the importance of knowledge dissemination and development in their professional outcomes [

53,

54]. Given this evidence, it is plausible that a focus on knowledge dissemination is informally put in place at the university hospital, thus deeming this condition either absent (Conf 3, and 5—

Table 6) or non-relevant for some configurations leading to the presence (Conf 4) and absence (Conf 1, and 2—

Table 7) of quality of care.

RQ5: Results show five configurations leading to the presence of quality of care (

Table 6). The alternative number of configurations leading to the same outcome reveals several pathways to be translated into different managerial strategies. Two configurations show circumstances where quality of care occurs when individual characteristics are present and one of the organizational characteristics is absent (Conf 4, and 5—

Table 6). As such, even in circumstances where the organizational characteristics are difficult to achieve, quality of care can thrive if social support and social networks are fostered. Similarly, one configuration leading to the presence of quality of care also requires the presence of both organizational characteristics even if social support is absent (Conf 1—

Table 6). Such results underpin the flexibility of conditions required to achieve quality of care. Two additional configurations (Conf 2, and 3—

Table 6) show mixed scenarios, where circumstances contributing to quality of care relied on the combination of both presence and absence of individual and organizational characteristics alike. This conveys an extended framework of analysis that provides insight over possible interventions to maximize quality of care in the university hospital context. Nonetheless, the results also show that all configurations required the combination of three conditions for the presence of quality of care. Therefore, the presence of quality of care is possible to achieve under alternative pathways, but it is more demanding in terms of the number of involved conditions than the alternative pathways to achieve than its absence.

RQ6: The results show three configurations leading to the absence of quality of care (

Table 7) involving fewer circumstances than the configurations that lead to quality of care (each one requires only the combination of two conditions). That is, the absence of quality of care seems easier to achieve, being less demanding in terms of the number of involved conditions. Contrary to the configurations leading to the presence of quality of care, all configurations leading to the absence of quality care involve a combination of the absences of conditions, supporting the literature review a contrario. Furthermore, results show there are no configurations combining organizational or individual conditions alone. The three configurations leading to the absence of quality care involve mixed-based combinations of conditions. Such a mixed nature of the configurations shows that the absence of quality care is a reflex of a systems’ failure; it stresses caution when considering how flexible and pervasive the absence of quality of care can be in circumstances where both individual and organizational characteristics are not assessed together.

6. Conclusions

We propose that both the individual and organizational conditions of the study contribute to the quality of care provided to patients through alternative and complex configurations that back managerial practices, personnel engagement, and measurement control of internal and external factors [

56,

57]. Analyzing quality of care can be a complex endeavor. As a performance measure, quality of care is related to organizational structures, processes, and outcomes that rely on interdependence to achieve safe and improved medical care [

38]. Given this rationale, our findings show that there are more paths leading to quality of care than to its absence. Our results also allow us to explore and verify fsQCA characteristics: there are different configurations for both the presence and absence of quality of care (asymmetry), hinting at different strategies that can be deployed in pursuing presence and fighting the absence of quality of care. Namely, managers should make available the circumstances to ensure the combinatory alternatives in

Table 6. Oppositely, they should avoid the existence of the three configurations revealed in

Table 7. Such quests demand managerial decision making involving both individual and organizational level conditions. Therefore, our conclusions challenge managers to add to the quality of care delivered to patients beyond the medical (technical and resource based) support of such health service.

While there are no necessary conditions for the quality of care provided to patients, or it absence, the results show that there are combinations of conditions that are sufficient in contributing to quality of care. There are also “dark” combinations of conditions the lead to the absence of such quality care. The alternative ways to generate quality of care are more numerous than the ones resulting in the absence of such care, which is good news. Our study provides several contributions. We assess complex causal relationship between individual and organizational characteristics leading to improved quality of care, and its absence. Accordingly, we discuss and provide insight towards possible paths for improving quality of care that can be pursued. Conversely, by providing insight over the pathways that also lead to the absence of quality of care, we promote a call to action on what to avoid.

To our knowledge, no previous study addresses both the presence and absence of quality of care. By extension, complex causal interaction of individual and organizational characteristics related to quality of care, while acknowledged [

2,

3,

4,

5,

38], remained unexplored so far. Our results show that, while complex, quality of care at a university hospital can be achieved under diverse circumstances. Thus, our findings lead us to conclude that the hospital should be focused on the promotion of managerial strategies that value interpersonal communication and knowledge sharing. The raining and development of leaders on ethical issues can improve the quality of care through the reinforcement and mimicry of appropriate behaviours and development of new ethical standards. Last, we recommend that additional efforts be conducted in the deployment and promotion of knowledge management frameworks in healthcare contexts, given their potential in achieving quality of care, in particular, when ethical leadership is perceived and paired with a supportive, robust social system inside the organization.