Genetic Determinants Associated with Persistence of Listeria Species and Background Microflora from a Dairy Processing Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Environmental Sample Collection from a Dairy Processing Plant

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Environmental Microflora

2.3. Sourcing of Listeria Isolates

2.4. DNA Extraction from Environmental Cultures and Listeria Isolates

2.5. Library Preparation and Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) of Listeria Isolates: Oxford Nanopore Corrected Assembly with Illumina Reads

2.6. Library Preparation, WGS, and Analysis of Environmental Microflora

2.7. Functional Annotation and Subsystem Analysis Using RAST

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Listeria Isolates Typing

3.2. Characterization and Comparison of the Microflora from Environmental Culture

3.3. Characterization and Comparison of the Subsystems Identified from Environmental Cultures and Listeria Isolates

3.3.1. Cell Wall and Capsule Category

3.3.2. Membrane Transport Category

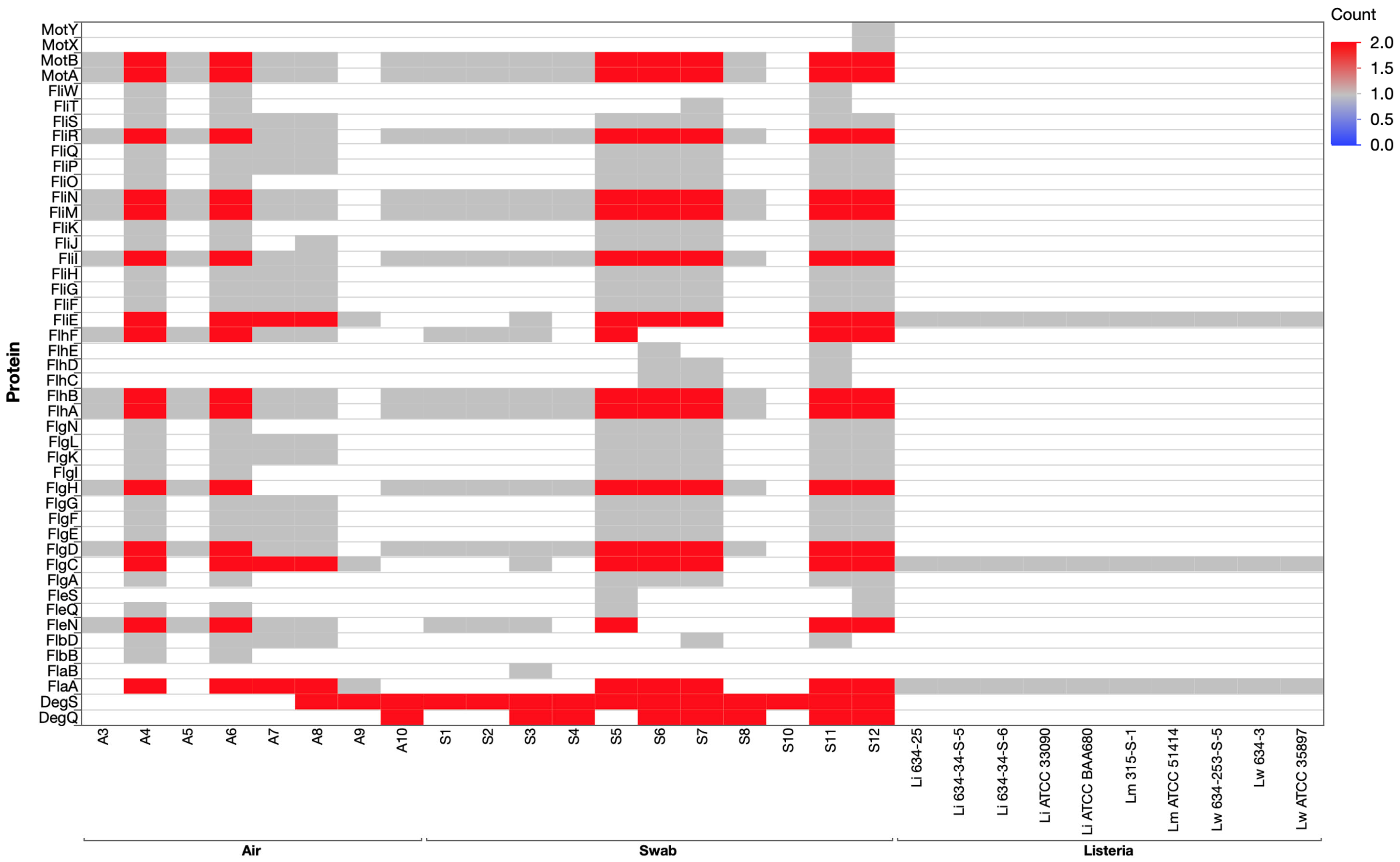

3.3.3. Motility and Chemotaxis Category and Dormancy and Sporulation Category

3.3.4. Regulation and Cell Signaling Category

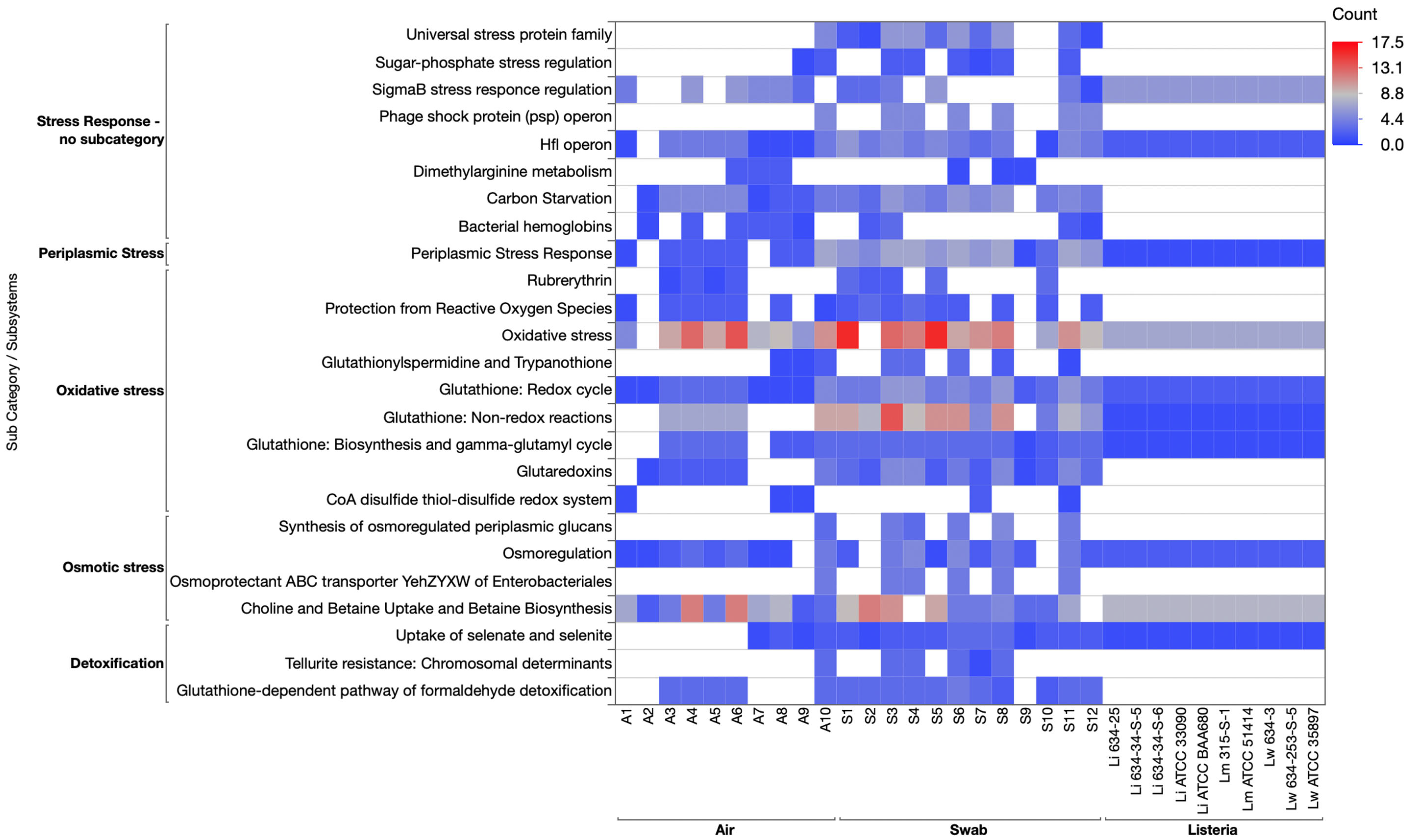

3.3.5. Stress Response Category

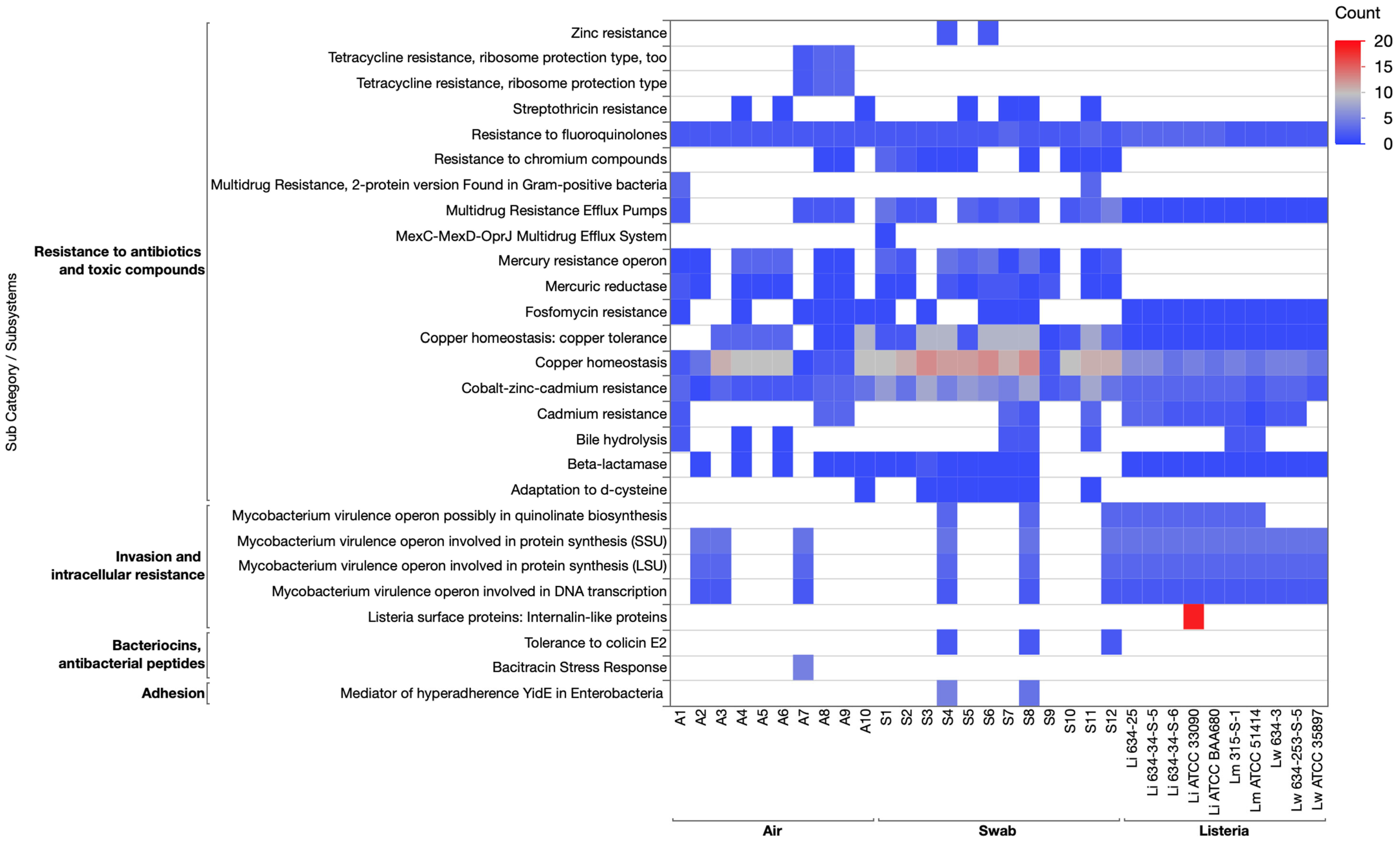

3.3.6. Virulence and Disease Category

3.3.7. Genomic Comparison of Subsystems in Listeria and Environmental Cultures

3.3.8. Comparing Genomic Determinants of Persistence Among Listeria Species

3.4. Characterization and Comparison of Functional Roles Assigned to Listeria Isolates and Environmental Cultures

3.4.1. Flagellar Assembly and Motility Genes in Listeria Isolates and Environmental Cultures

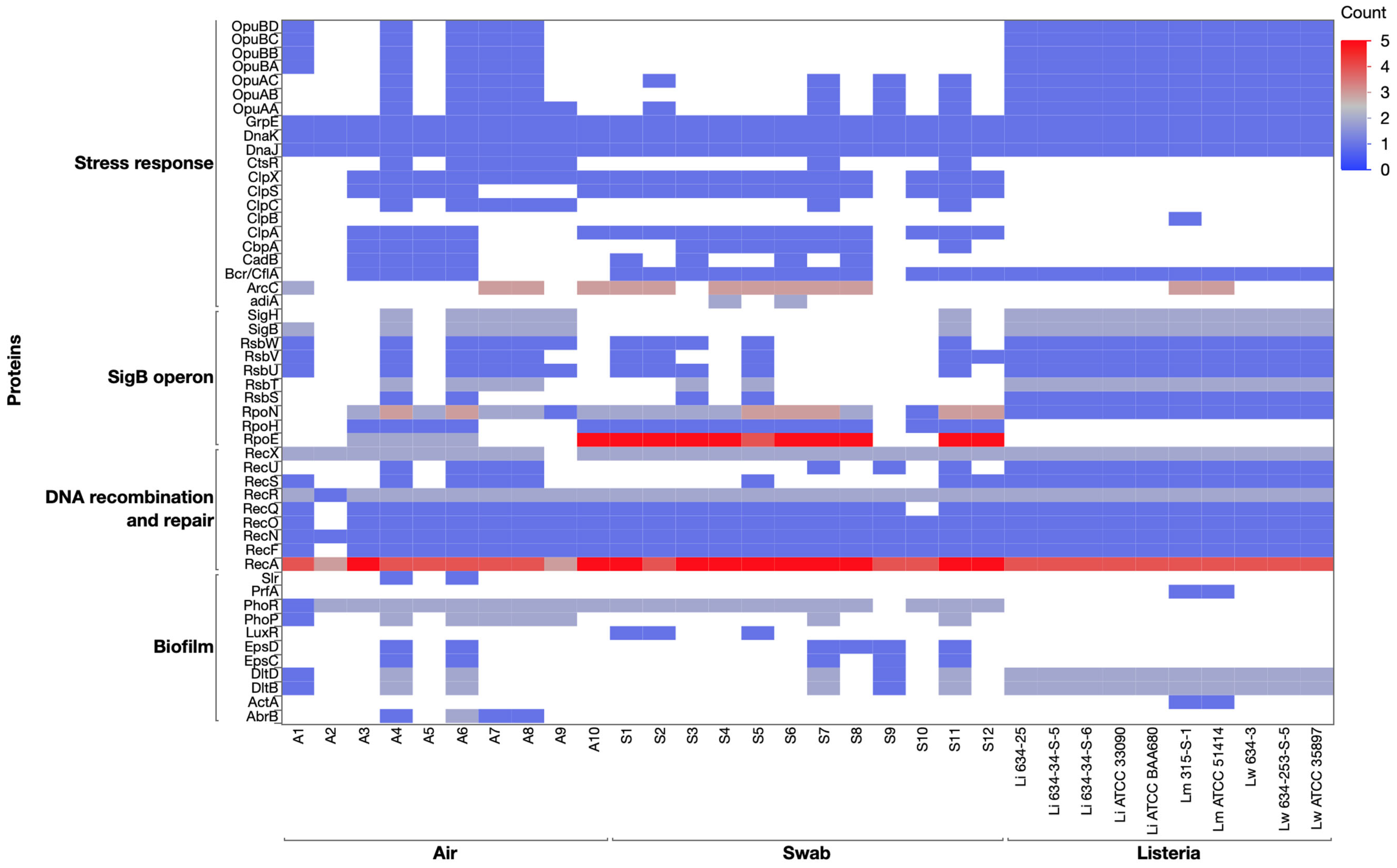

3.4.2. Biofilm-Associated Genes in Listeria Isolates and Environmental Cultures

3.4.3. Stress Response Genes: The SigB Operon and Alternative Sigma Factors

3.4.4. DNA Repair and Recombination Genes in Listeria Isolates and Environmental Cultures

3.4.5. Stress Response Genes in Listeria and Environmental Isolates

3.4.6. Comparison and Contextual Considerations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Lm | Listeria monocytogenes |

| FPEs | Food processing environments |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight |

| Lw | Listeria welshimeri |

| Li | Listeria innocua |

| MLST | Multi-locus sequence typing |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| RAST | Rapid annotations utilizing subsystems technology |

References

- Di Ciccio, P.; Rubiola, S.; Panebianco, F.; Lomonaco, S.; Allard, M.; Bianchi, D.M.; Civera, T.; Chiesa, F. Biofilm formation and genomic features of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from meat and dairy industries located in Piedmont (Italy). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 378, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. About Listeria Infection. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/about/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- CDC. How Listeria Spread: Soft Cheeses and Raw Milk. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/causes/dairy.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Ice Cream—August 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-08-23/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Ice Cream—June 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/monocytogenes-06-22/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- CDC. Listeria Outbreak Linked to Supplement Shakes. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/shakes-022025/index.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Osek, J.; Lachtara, B.; Wieczorek, K. Listeria monocytogenes—How this pathogen survives in food-production environments? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 866462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Silva, V.; Gomes, J.P.; Coelho, A.; Batista, R.; Saraiva, C.; Esteves, A.; Martins, Â.; Contente, D.; Diaz-Formoso, L. Listeria monocytogenes from food products and food associated environments: Antimicrobial resistance, genetic clustering and biofilm Insights. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, F.; Rossi, C.; Chiaverini, A.; Ruolo, A.; Orsini, M.; Centorame, P.; Acciari, V.A.; López, C.C.; Salini, R.; Torresi, M. Genetic relationships and biofilm formation of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from the smoked salmon industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 356, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unrath, N.; McCabe, E.; Macori, G.; Fanning, S. Application of whole genome sequencing to aid in deciphering the persistence potential of Listeria monocytogenes in food production environments. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdová, A.; Véghová, A.; Minarovičová, J.; Drahovská, H.; Kaclíková, E. The Relationship between Biofilm Phenotypes and Biofilm-Associated Genes in Food-Related Listeria monocytogenes Strains. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heir, E.; Møretrø, T.; Simensen, A.; Langsrud, S. Listeria monocytogenes strains show large variations in competitive growth in mixed culture biofilms and suspensions with bacteria from food processing environments. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 275, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, A.; Møretrø, T.; Heir, E.; Briandet, R.; Langsrud, S. Cleaning and disinfection of biofilms composed of Listeria monocytogenes and background microbiota from meat processing surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01046-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Rizzotti, L.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S. Horizontal gene transfer among microorganisms in food: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolon, M.L.; Voloshchuk, O.; Bartlett, K.V.; LaBorde, L.F.; Kovac, J. Multi-species biofilms of environmental microbiota isolated from fruit packing facilities promoted tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes to benzalkonium chloride. Biofilm 2024, 7, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafuna, T.; Matle, I.; Magwedere, K.; Pierneef, R.; Reva, O. Comparative genomics of Listeria species recovered from meat and food processing facilities. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01189-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poswal, V.; Anand, S.; Kraus, B. Characterizing Environmental Background Microflora and Assessing Their Influence on Listeria Persistence in Dairy Processing Environment. Foods 2025, 14, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaser, R.; Sović, I.; Nagarajan, N.; Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T. The BLAST sequence analysis tool. In The NCBI Handbook; National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Stessl, B.; Wagner, M.; Ruppitsch, W. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. In Listeria Monocytogenes: Methods and Protocols; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothrock, M.J., Jr.; Fan, P.; Jeong, K.C.; Kim, S.A.; Ricke, S.C.; Park, S.H. Complete genome sequence of Listeria monocytogenes strain MR310, isolated from a pastured-flock poultry farm system. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00171-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Chen, Y.; Gorski, L.; Ward, T.J.; Osborne, J.; Kathariou, S. Listeria monocytogenes source distribution analysis indicates regional heterogeneity and ecological niche preference among serotype 4b clones. MBio 2018, 9, e00396-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Fang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Bi, J.; Wang, J.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, H. Persistence of Listeria monocytogenes ST5 in ready-to-eat food processing environment. Foods 2022, 11, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleto, S.; Matos, S.; Kluskens, L.; Vieira, M.J. Characterization of contaminants from a sanitized milk processing plant. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolon, M.L.; Chandross-Cohen, T.; Kaylegian, K.E.; Roberts, R.F.; Kovac, J. Context matters: Environmental microbiota from ice cream processing facilities affected the inhibitory performance of two lactic acid bacteria strains against Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e01167-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, A.; Langsrud, S.; Møretrø, T. Microbial diversity and ecology of biofilms in food industry environments associated with Listeria monocytogenes persistence. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 37, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.T.; Lefcourt, A.M.; Nou, X.; Shelton, D.R.; Zhang, G.; Lo, Y.M. Native microflora in fresh-cut produce processing plants and their potentials for biofilm formation. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-H.; Cole, S.; Badel-Berchoux, S.; Guillier, L.; Felix, B.; Krezdorn, N.; Hébraud, M.; Bernardi, T.; Sultan, I.; Piveteau, P. Biofilm formation of Listeria monocytogenes strains under food processing environments and pan-genome-wide association study. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijgrok, G.; Wu, D.-Y.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Codée, J.D. Synthesis and application of bacterial exopolysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 78, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W.; Fisher, J.F.; Mobashery, S. Bacterial cell-wall recycling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1277, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trappetti, C.; Kadioglu, A.; Carter, M.; Hayre, J.; Iannelli, F.; Pozzi, G.; Andrew, P.W.; Oggioni, M.R. Sialic acid: A preventable signal for pneumococcal biofilm formation, colonization, and invasion of the host. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, V.; Frank, O.; Bartling, P.; Scheuner, C.; Göker, M.; Brinkmann, H.; Petersen, J. Biofilm plasmids with a rhamnose operon are widely distributed determinants of the ‘swim-or-stick’lifestyle in roseobacters. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2498–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chepkwony, N.K.; Brun, Y.V. A polysaccharide deacetylase enhances bacterial adhesion in high-ionic-strength environments. Iscience 2021, 24, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, A.; Kline, K.A. Streptococcus pyogenes capsule promotes microcolony-independent biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00052-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ge, C. Biofilm formation and control of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abby, S.S.; Cury, J.; Guglielmini, J.; Néron, B.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P. Identification of protein secretion systems in bacterial genomes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backert, S.; Meyer, T.F. Type IV secretion systems and their effectors in bacterial pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.-T.; Tyler, B.M.; Setubal, J.C. Protein secretion systems in bacterial-host associations, and their description in the Gene Ontology. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.A.; Turner, D.P. The role of bacterial ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in pathogenesis and virulence: Therapeutic and vaccine potential. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 171, 105734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiara, M.; Caruso, M.; D’Erchia, A.M.; Manzari, C.; Fraccalvieri, R.; Goffredo, E.; Latorre, L.; Miccolupo, A.; Padalino, I.; Santagada, G. Comparative genomics of Listeria sensu lato: Genus-wide differences in evolutionary dynamics and the progressive gain of complex, potentially pathogenicity-related traits through lateral gene transfer. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 2154–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.H.; Idris, A.L.; Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jin, X.; Qiu, J.; Guan, X.; Huang, T. Beyond risk: Bacterial biofilms and their regulating approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.M.; Aranda, B. Microbial growth under limiting conditions-future perspectives. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugo, A.J.; Watnick, P.I. Vibrio cholerae CytR is a repressor of biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Oliver, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.Z.; Hirata, H.; Tsuyumu, S. CytR homolog of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum controls air-liquid biofilm formation by regulating multiple genes involved in cellulose production, c-di-GMP signaling, motility, and type III secretion system in response to nutritional and environmental signals. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Preston, J.F., III; Romeo, T. The pgaABCD locus of Escherichia coli promotes the synthesis of a polysaccharide adhesin required for biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2724–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Yadav, M.; Ghosh, C.; Rathore, J.S. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin modules: Classification, functions, and association with persistence. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhai, Y.; Wei, M.; Zheng, C.; Jiao, X. Toxin–antitoxin systems: Classification, biological roles, and applications. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 264, 127159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, B.; Melero, B.; Stessl, B.; Jaime, I.; Wagner, M.; Rovira, J.; Rodríguez-Lázaro, D. The response to oxidative stress in Listeria monocytogenes is temperature dependent. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Wu, K.; Lee, C. Stress-responsive periplasmic chaperones in bacteria. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 678697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olubisose, E.T.; Ajayi, A.; Adeleye, A.I.; Smith, S.I. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of efflux pump and biofilm in multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella Serovars isolated from food animals and handlers in Lagos Nigeria. One Health Outlook 2021, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, A.B.; Carrara, J.A.; Barroso, C.D.N.; Tuon, F.F.; Faoro, H. Role of efflux pumps on antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.-X.; Anupoju, S.M.B.; Nguyen, A.; Zhang, H.; Ponder, M.; Krometis, L.-A.; Pruden, A.; Liao, J. Evidence of horizontal gene transfer and environmental selection impacting antibiotic resistance evolution in soil-dwelling Listeria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, C.H.; Dahdouh, E.; SanJose, C.; Orgaz, B. Listeria monocytogenes colonizes Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilms and induces matrix over-production. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voglauer, E.M.; Alteio, L.V.; Pracser, N.; Thalguter, S.; Quijada, N.M.; Wagner, M.; Rychli, K. Listeria monocytogenes colonises established multispecies biofilms and resides within them without altering biofilm composition or gene expression. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 292, 127997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, O.K.; Ndahetuye, J.B.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Ricke, S.C.; Crandall, P.G. Influence of Listeria innocua on the attachment of Listeria monocytogenes to stainless steel and aluminum surfaces. Food Control 2014, 39, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawiasa, A.; Schmidt, M.; Olejnik-Schmidt, A. Phage-Based Control of Listeria innocua in the Food Industry: A Strategy for Preventing Listeria monocytogenes Persistence in Biofilms. Viruses 2025, 17, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, L.; Onyeaka, H.; O’Neill, S. Listeria monocytogenes biofilms in food-associated environments: A persistent enigma. Foods 2023, 12, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galie, S.; García-Gutiérrez, C.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J.; Lombó, F. Biofilms in the food industry: Health aspects and control methods. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.-C.; Lee, M.-A.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, K.-H. Role of DegQ in differential stability of flagellin subunits in Vibrio vulnificus. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraquet, C.; Harwood, C.S. Cyclic diguanosine monophosphate represses bacterial flagella synthesis by interacting with the Walker A motif of the enhancer-binding protein FleQ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18478–18483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halte, M.; Andrianova, E.P.; Goosmann, C.; Chevance, F.F.; Hughes, K.T.; Zhulin, I.B.; Erhardt, M. FlhE functions as a chaperone to prevent formation of periplasmic flagella in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzantini, D.; Celandroni, F.; Salvetti, S.; Gueye, S.A.; Lupetti, A.; Senesi, S.; Ghelardi, E. FlhF is required for swarming motility and full pathogenicity of Bacillus cereus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, A.E.; Weaver, A.A.; Dimkovikj, A.; Shrout, J.D. Assessing travel conditions: Environmental and host influences on bacterial surface motility. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00014-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K. SlrR/SlrA controls the initiation of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 69, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Kearns, D.B.; McLoon, A.; Chai, Y.; Kolter, R.; Losick, R. A novel regulatory protein governing biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P. Extracellular polymeric substances, a key element in understanding biofilm phenotype. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Lu, R.; Liu, F.; Ye, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, M. Identification of LuxR family regulators that integrate into quorum sensing circuit in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 691842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Ayala, F.; Bartolini, M.; Grau, R. The stress-responsive alternative sigma factor SigB of Bacillus subtilis and its relatives: An old friend with new functions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, B.E.; Seshu, J. STAS domain only proteins in bacterial gene regulation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 679982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q. Alternative sigma factor RpoX is a part of the RpoE regulon and plays distinct roles in stress responses, motility, biofilm formation, and hemolytic activities in the marine pathogen Vibrio alginolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00234-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Bi, W.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, X. Regulatory function of sigma factors RpoS/RpoN in adaptation and spoilage potential of Shewanella baltica. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikedal, K.; Ræder, S.B.; Riisnæs, I.M.; Bjørås, M.; Booth, J.; Skarstad, K.; Helgesen, E. RecN and RecA orchestrate an ordered DNA supercompaction response following ciprofloxacin exposure in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, J.; Bardina, C.; Beceiro, A.; Rumbo, S.; Cabral, M.P.; Barbé, J.; Bou, G. Acinetobacter baumannii RecA protein in repair of DNA damage, antimicrobial resistance, general stress response, and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3740–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslowska, K.H.; Makiela-Dzbenska, K.; Fijalkowska, I.J. The SOS system: A complex and tightly regulated response to DNA damage. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2019, 60, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Das, S. Acid-tolerant bacteria and prospects in industrial and environmental applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3355–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.; Butcher, J.; Stintzi, A. Stress responses, adaptation, and virulence of bacterial pathogens during host gastrointestinal colonization. In Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 385–411. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, S.; Scarlato, V.; Roncarati, D. The Helicobacter pylori HspR-modulator CbpA is a multifunctional heat-shock protein. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, R.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Z. Protein interaction network analysis to investigate stress response, virulence, and antibiotic resistance mechanisms in Listeria monocytogenes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Chattoraj, P.; Biswas, I. CtsR regulation in mcsAB-deficient Gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, T.; Buys, E.M. Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis: The role of stress adaptation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.; Wensing, A.; Brosius, M.; Steil, L.; Völker, U.; Bremer, E. Osmotic control of opuA expression in Bacillus subtilis and its modulation in response to intracellular glycine betaine and proline pools. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Chatterjee, D.; Sarkar, N.; Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Ray, R.R. Multi-omics Technology in Detection of Multispecies Biofilm. Microbe 2024, 4, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Listeria Isolate | Pasteur ID | Clonal Complex (CC) | Sublineage (SL) | Phylogenetic Lineage | cgMLST Type | Sequence Type (ST) | Novel Alleles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li 634-25 | 101847 | CC1008 | N.A. | L. innocua | N.A. | ST3137 | 68 |

| Li 634-34-S-5 | 101848 | CC1008 | SL1008 | L. innocua | N.A. | ST1008 | 65 |

| Li 634-34-S-6 | 101849 | CC1489 | 1489 | L. innocua | N.A. | ST1489 | 200 |

| Li ATCC 33090 | 101852 | ST139 | SL139 | L. innocua | N.A. | ST139 | 155 |

| Li ATCC BAA 680 | 101851 | CC140 | SL140 | L. innocua | N.A. | ST140 | 78 |

| Lm 315-S-1 | 101844 | CC5 | SL5 | I | N.A. | ST5 | 19 |

| Lm ATCC 51414 | 101853 | CC4 | SL5 | I | CT13172 | ST55 | 8 |

| Lw 634-3 | 101845 | ST2688 | 2688 | L. welshimeri | N.A. | ST2688 | 476 |

| Lw 634-253-S-5 | 101846 | ST2688 | SL2688 | L. welshimeri | CT13173 | ST2688 | 467 |

| Lw ATCC 35897 | 101850 | CC129 | SL129 | L. welshimeri | N.A. | ST129 | 116 |

| Sample Type | Sample ID | 16S rRNA Identification | MALDI-TOF MS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greatest Identity % | Identity | |||

| Air | A1 | 97.893–99.933 | Staphylococcus pasteuri | Staphylococcus pasteuri |

| A2 | 99.858–99.929 | Micrococcus aloeverae | Micrococcus luteus | |

| A3 | 99.352–99.545 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | |

| 99.35 | Stenotrophomonas forensis | |||

| A4 | 99.74–99.935 | Bacillus halotolerans | Bacillus sp. | |

| 99.458 | Stenotrophomonas lactitubi | |||

| 99.584–99.722 | Stenotrophomonas cyclobalanopsidis | |||

| A6 | 99.722 | Stenotrophomonas cyclobalanopsidis | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | |

| 99.74–99.935 | Bacillus halotolerans | |||

| A7 | 99.796–100 | Rummeliibacillus stabekisii | Staphylococcus epidermidis | |

| A8 | 99.73 | Paenibacillus glucanolyticus | Rummeliibacillus stabekisii | |

| 99.257–100 | Rummeliibacillus stabekisii | |||

| A9 | 99.19–99.932 | Paenibacillus glucanolyticus | Paenibacillus glucanolyticus | |

| A10 | 99.655–99.793 | Pantoea agglomerans | Staphylococcus warneri | |

| Swab | S1 | 99.993–100 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| S2 | 99.33–100 | Ectopseudomonas oleovorans | Pseudomonas oleovorans | |

| S3 | 99.25–99.386 | Pseudomonas oryzihabitans | Raoultella ornithinolytica | |

| 99.725–99.862 | Raoultella terrigena | |||

| S4 | 99.793–99.862 | Lelliottia amnigena | Citrobacter gillenii | |

| 99.672–99.803 | Citrobacter gillenii | |||

| 99.503–99.858 | Citrobacter arsenatis | |||

| S5 | 99.725–99.863 | Pseudomonas koreensis | Pseudomonas koreensis | |

| S6 | 99.48–99.87 | Aeromonas hydrophila | Raoultella ornithinolytica | |

| 99.558 | Morganella morganii subsp. sibonii | |||

| 99.582 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | |||

| 99.851 | Klebsiella grimontii | |||

| 99.714–99.93 | Raoultella planticola | |||

| 99.787 | Citrobacter arsenatis | |||

| 100 | Huaxiibacter chinensis | |||

| S7 | 99.8–99.933 | Lactococcus lactis | Raoultella planticola | |

| 99.798–99.865 | Enterococcus gallinarum | |||

| 99.41–99.705 | Morganella morganii subsp. sibonii | |||

| 98.498–98.567 | Providencia heimbachae | |||

| 98.372–98.641 | Providencia burhodogranariea | |||

| S8 | 99.591–99.659 | Serratia marcescens | Serratia marcescens | |

| 99.41–99.705 | Morganella morganii subsp. sibonii | |||

| 99.933 | Lactococcus lactis | |||

| 99.786–100 | Raoultella planticola | |||

| S9 | 100 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | |

| S10 | 99.589–99.795 | Acinetobacter lwoffii | Rahnella aquatilis | |

| 99.717–99.788 | Prolinoborus fasciculus | |||

| S11 | 99.391–99.661 | Rahnella inusitata | Exiguobacterium mexicanum | |

| 99.914 | Exiguobacterium artemiae | |||

| 100 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | |||

| S12 | 99.218–99.87 | Shewanella xiamenensis | Shewanella oneidensis | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Poswal, V.; Anand, S.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, J.L.; Kraus, B. Genetic Determinants Associated with Persistence of Listeria Species and Background Microflora from a Dairy Processing Environment. Appl. Microbiol. 2026, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010020

Poswal V, Anand S, Gonzalez-Hernandez JL, Kraus B. Genetic Determinants Associated with Persistence of Listeria Species and Background Microflora from a Dairy Processing Environment. Applied Microbiology. 2026; 6(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010020

Chicago/Turabian StylePoswal, Vaishali, Sanjeev Anand, Jose L. Gonzalez-Hernandez, and Brian Kraus. 2026. "Genetic Determinants Associated with Persistence of Listeria Species and Background Microflora from a Dairy Processing Environment" Applied Microbiology 6, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010020

APA StylePoswal, V., Anand, S., Gonzalez-Hernandez, J. L., & Kraus, B. (2026). Genetic Determinants Associated with Persistence of Listeria Species and Background Microflora from a Dairy Processing Environment. Applied Microbiology, 6(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010020