Effect of K-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil K Content, Plant K Uptake, and Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in a Dyke Area in Field Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Experimental Methods

- Plant height (cm): measured from the soil surface to the top of the highest leaf.

- Stem diameter (cm): measured at the basal, middle, and upper parts of the stem, then averaged.

- Number of leaves (leaves plant−1): counted as the total number of leaves per plant.

- Ear set height (cm): measured from the soil surface to the node of the first ear.

- Ear length (cm): measured from the base to the tip of the ear.

- Number of rows per ear (rows ear−1): total number of rows of kernels on each ear.

- Ear diameter (cm): measured at three positions along the ear and averaged.

- Number of kernels per row (kernels row−1): counted on one kernel row of the ear.

- Hundred-kernel weight (g): weight of one hundred kernels from each plot.

- Grain yield (t ha−1): all ears in each plot were harvested, weighed fresh, air-dried, shelled, and adjusted to 15.5% moisture content.

- pH (H2O and KCl) was determined by extracting soil with distilled water and 1.0 M KCl at a ratio of 1:2.5, then measured with a pH meter. Electrical conductivity (EC) was measured from the soil–water extract used for pH (H2O).

- Total N was determined by the Kjeldahl method and titrated with 0.01 N H2SO4. Available N (NH4+ and NO3−) was determined from soil extracted with 2.0 M KCl at a ratio of 1:10, then measured spectrophotometrically at 650.0 and 540.0 nm, respectively.

- Soluble P was determined by Bray II extraction. Total P was determined by digesting soil with concentrated H2SO4 and HClO4. Insoluble P (Al-P, Fe-P, Ca-P) was extracted sequentially with 25 mL 0.5 M NH4F, 25 mL 0.1 M NaOH, and 25 mL 2.5 M H2SO4, respectively. All P fractions were measured spectrophotometrically at 880.0 nm.

- Organic matter was determined by the Walkley–Black method.

- Exchangeable cations (K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+) were extracted with 0.1 N BaCl2 and measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry at 766.5, 589.0, 422.7, and 285.5 nm, respectively. For cation-exchange capacity (CEC), the cation-extracted soil was subsequently extracted with 0.02 M MgSO4, and the solution was titrated with 0.01 M EDTA.

3. Results

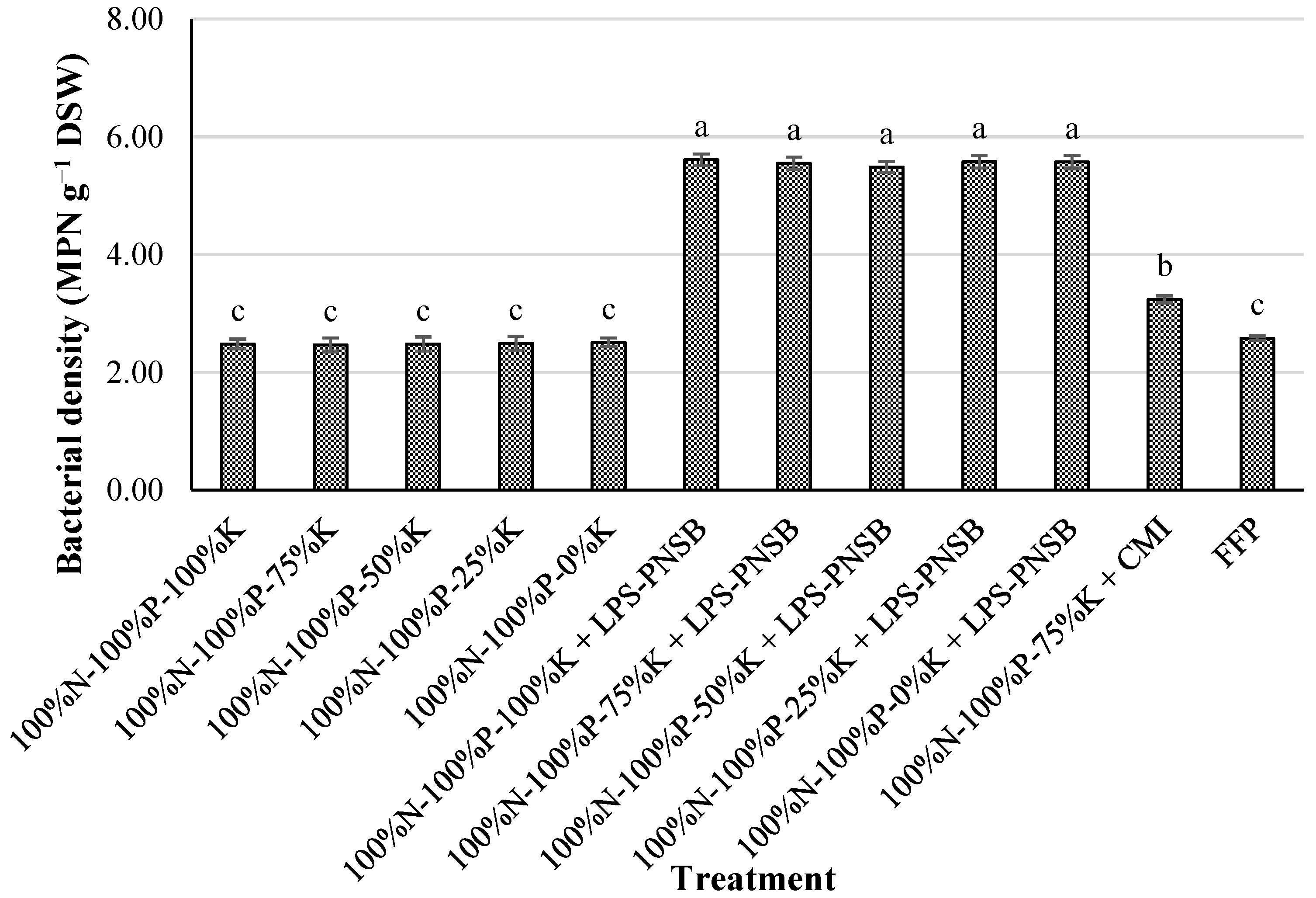

3.1. Effects of Liquid Potassium-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil Properties of Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area of An Phu, An Giang

3.2. Effects of Liquid Potassium-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on K Uptake in Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area of An Phu, An Giang

3.3. Effects of Liquid Potassium-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on the Growth of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area of An Phu, An Giang

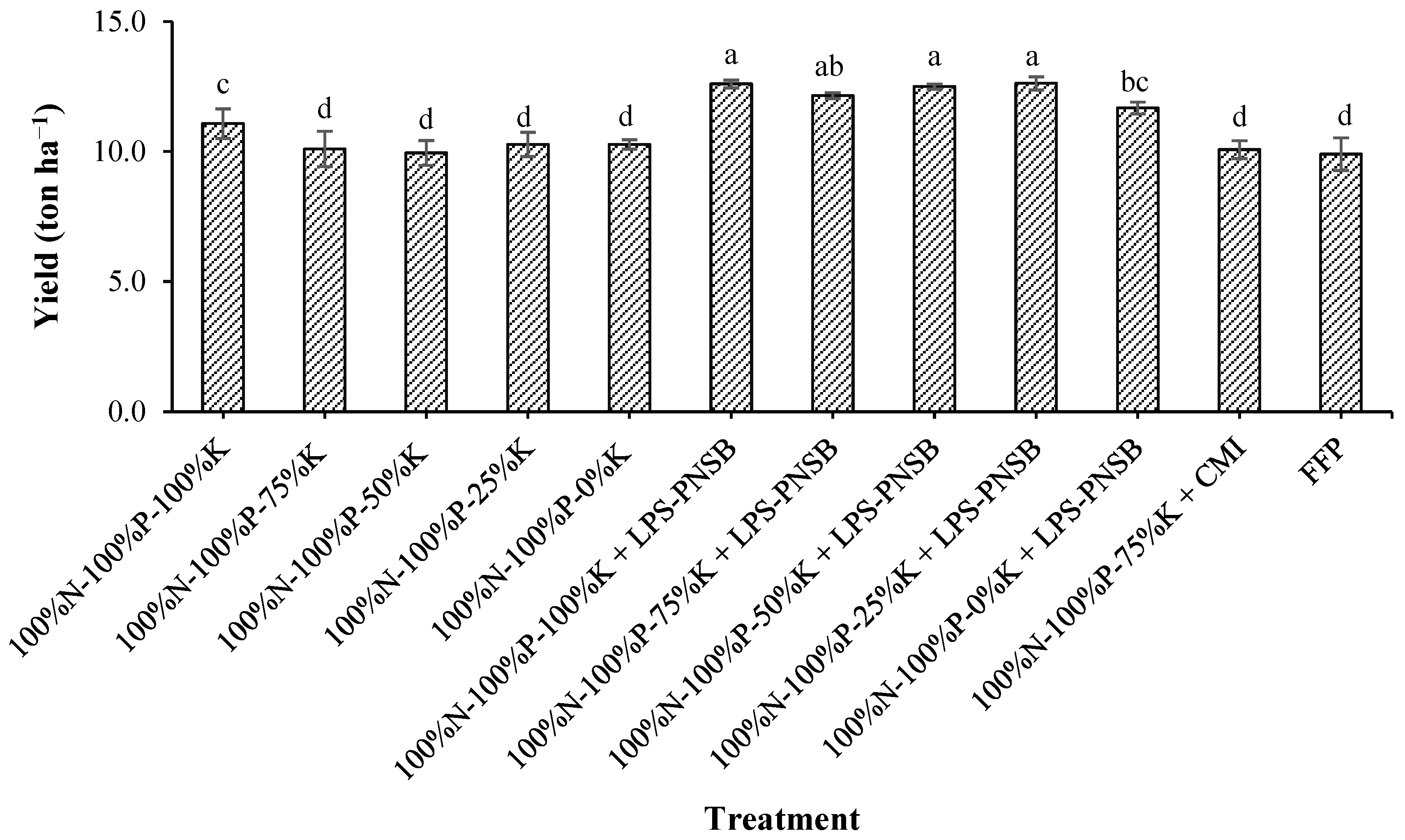

3.4. Effects of Liquid Potassium-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on the Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area of An Phu, An Giang

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Properties of Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area Under Hybrid Maize Cultivation

4.2. Potassium Uptake in Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area

4.3. Growth of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area

4.4. Grain Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in the Dyke-Protected Area

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALA | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| CEC | Cation-exchange capacity |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| CMI | Commercial microbial inoculant |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| EPSs | Exopolymeric substances |

| GA | Gibberellic acid |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| K | Potassium |

| LPS-PNSB | Liquid potassium-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria |

| PNSB | Purple nonsulfur bacteria |

References

- Alvarenga, I.C.; Dainton, A.N.; Aldrich, C.G. A Review: Nutrition and Process Attributes of Corn in Pet Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8567–8576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oas, S.E.; Adams, K.R. The Nutritional Content of Five Southwestern US Indigenous Maize (Zea Mays L.) Landraces of Varying Endosperm Type. Am. Antiq. 2022, 87, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock Products. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Nguyen, P.C.; Vu, P.T.; Minh, V.Q.; Tri, L.Q.; Khuong, N.Q. Development of Criteria for High-Technology Rice and Corn Suitability Assessment—A Case Study in the An Giang Province, Viet Nam. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, C.T.; Lan, T.H.P.; Labor, F.; Long, T.X.; Dinh, T.T.; Tam, N.T.; Duc, V.T.; Berg, H. Farmers’ Perceived Impact of High-Dikes on Rice and Wild Fish Yields, Water Quality, and Use of Fertilizers in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutaryono, Y.A.; Putra, R.A.; Mardiansyah, M.; Yuliani, E.; Harjono, H.; Mastur, M.; Sukarne, S.; Enawati, L.; Dahlanuddin, D. Mixed Leucaena and Molasses Can Increase the Nutritional Quality and Rumen Degradation of Corn Stover Silage. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2023, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thenveettil, N.; Reddy, K.N.; Reddy, K.R. Effects of Potassium Nutrition on Corn (Zea mays L.) Physiology and Growth for Modeling. Agriculture 2024, 14, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantray, J.; Anand, A.; Dash, B.; Ghosh, M.K.; Behera, A.K. Silicate Minerals—Potential Source of Potash—A Review. Miner. Eng. 2022, 179, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Shafique, B.; Khalid, W.; Nadeem, H.R.; Mueen-ud-Din, G.; Khalid, M.Z. Applications of Biotechnology in Food and Agriculture: A Mini-Review. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 92, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Kerr, W.A. Biotechnology in China—Regulation, Investment, and Delayed Commercialization. GM Crops Food 2022, 13, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Recent Advancements for Microorganisms and Their Natural Compounds Useful in Agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glockow, T.; Kaster, A.K.; Rabe, K.S.; Niemeyer, C.M. Sustainable Agriculture: Leveraging Microorganisms for a Circular Economy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.N.; Xu, M.T.; Uwiringiyimana, E. Isolation of Highly Efficient Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Effects on Nutrient Acquisition and Growth Promotion in Tobacco Seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinets, T.V.; Greenwood, D.J. Potassium Dynamics. In Handbook of Processes and Modeling in the Soil-Plant System; Nieder, R., Benbi, D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 525–559. [Google Scholar]

- Jini, D.; Ganga, V.S.; Greeshma, M.B.; Sivashankar, R.; Thirunavukkarasu, A. Sustainable Agricultural Practices Using Potassium-Solubilizing Microorganisms (KSMs) in Coastal Regions: A Critical Review on the Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 13641–13664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoniyi, A.S.; Adeyemo, A.J.; Agbenin, J.O.; Ilori, A.O.; da Silva Oliveira, D.M.; de Freitas, D.A.F. Potassium Release from K-Bearing Minerals Treated with Organic Acids under Laboratory Conditions. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, A.; Hamid, M.R.; Li, C.; Du, J.; Cheng, J.; Tan, X.; Zhen, L.; et al. Characterization of Rhodopseudomonas palustris Population Dynamics on Tobacco Phyllosphere and Induction of Plant Resistance to Tobacco Mosaic Virus. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, L.S.; Yen, K.S.; Chang, Y.T.; Chao, Y.Y. Utilization of Rhodopseudomonas palustris in Crop Rotation Practice Boosts Rice Productivity and Soil Nutrient Dynamics. Agriculture 2024, 14, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Sundar, L.S.; Tu, Y.K.; Chao, Y.Y. Exploring the Potential of Purple Non-Sulfur Bacteria Strains A3-5 and F3-3 in Sustainable Agriculture: A Study on Nutrient Solubilization, Plant Growth Promotion, and Acidic Stress Tolerance. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 2294–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, I. Potential of Phototrophic Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria to Fix Nitrogen in Rice Fields. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petushkova, E.; Mayorova, E.; Tsygankov, A. TCA Cycle Replenishing Pathways in Photosynthetic Purple Non-Sulfur Bacteria Growing with Acetate. Life 2021, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thu, L.T.M.; Quang, L.T.; Ngoc, V.Y.; Thuan, V.M.; Qui, N.Q.; Trong, N.D.; Nguyen, T.T.K.; Xuan, L.N.T.; Thuc, L.V.; Khuong, N.Q. Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria Affect Nutrient Uptake, Growth, and Yield of Hybrid Maize by Solubilizing Potassium in Dyked Alluvial Soil. Heliyon, 2025; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Zhang, F. Growth-Promoting Ability of Rhodopseudomonas palustris G5 and Its Effect on Induced Resistance in Cucumber against Salt Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.C.; Tsai, S.Y.; Chang, W.H.; Wu, I.C.; Sou, N.L.; Hung, S.H.W.; Chiang, E.I.; Huang, C.C. Characterization of the Pyrroloquinoline Quinone Producing Rhodopseudomonas palustris as a Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium under Photoautotrophic and Photoheterotrophic Culture Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, L.T.M.; Xuan, L.N.T.; Nhan, T.C.; Quang, L.T.; Trong, N.D.; Thuan, V.M.; Nguyen, T.T.K.; Nguyen, P.C.; Thuc, L.V.; Khuong, N.Q. Characterization of Novel Species of Potassium-Dissolving Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria Isolated from In-Dyked Alluvial Upland Soil for Maize Cultivation. Life 2024, 14, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuong, N.Q.; Thuc, L.V.; Duc, H.H.; Huu, T.N.; Van, T.T.; Thu, L.T.; Quang, L.T.; Xuan, D.T.; Nhan, T.C.; Xuan, N.T.; et al. Potential of N2-Fixing Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Maize Roots as Biofertiliser to Enhance Soil Fertility, N Uptake, and Yield of Zea mays L. Cultivated in Alluvial Soil in Dykes. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2022, 16, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houba, V.J.G.; Van Der Lee, J.J.; Novozamsky, I. Extraction of Trace Elements with 0.43 M Nitric Acid. In Soil and Plant Analysis, Part 1; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.L.; Page, A.L.; Helmke, P.A.; Loeppert, R.H.; Soltanpour, P.N.; Tabatabai, M.A.; Johnston, C.T.; Sumner, M.E. Methods of Soil Analysis. Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 3, pp. 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, N.; Nishiyama, M.; Otsuka, S.; Matsumoto, S. Effects of Inoculation of Phototrophic Purple Bacteria on Grain Yield of Rice and Nitrogenase Activity of Paddy Soil in a Pot Experiment. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2005, 51, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W. Enrichment and Isolation of Purple Non-Sulfur Bacteria; Department of Biological Sciences, College of Sciences, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi-Ghiri, M.; Niazi, M.; Khodabakhshi, M.; Boostani, H.R.; Owliaie, H.R. Mechanisms of Potassium Release from Calcareous Soils to Different Salt, Organic Acid and Inorganic Acid Solutions. Soil Res. 2019, 57, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, C.; Li, W.; Lin, L.; Liao, T.; Fan, X.; Peng, H.; An, Q.; Liang, Y. Phosphorus-, Potassium-, and Silicon-Solubilizing Bacteria from Forest Soils Can Mobilize Soil Minerals to Promote the Growth of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, L.A.; Klaic, R.; Bortoletto-Santos, R.; Ribeiro, C.; Farinas, C.S. Unveiling the Solubilization of Potassium Mineral Rocks in Organic Acids for Application as K-Fertilizer. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 2431–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettadili, H.; Aksoy, B.N.; Vural, C. Exploring the Plant Growth-Promoting Potential of a Purple Non-Sulfur Bacterium: Cereibacter sphaeroides PW15. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trong, N.D.; Trang, T.T.T.; Quang, L.T.; Oanh, T.O.; Nguyen, P.C.; Nhan, T.C.; Khuong, N.Q. Effects of Rhodopseudomonas palustris and Rhodopseudomonas pentothenatexigens on Reducing Chemical NPK Fertilizer Used for Rice in Acid Sulfate Soil under Field Conditions. Paddy Water Environ. 2025, 23, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Lur, H.S.; Liu, C.T. From Lab to Farm: Elucidating the Beneficial Roles of Photosynthetic Bacteria in Sustainable Agriculture. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Hua, Q.; Qiu, C.; Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Lin, X. The Long-Term Effects of Using Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria and Photosynthetic Bacteria as Biofertilizers on Peanut Yield and Soil Bacteria Community. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi-Saeidlou, S.; Rasouli-Sadaghiani, M.; Samadi, A.; Barin, M.; Sepehr, E. Study of Silicate-Solubilizing Microorganisms Impact on the Dissolution of Soil Non-Exchangeable Potassium, Growth Indices of Maize (Zea mays L.), and Nutrient Uptake. Appl. Soil Res. 2025, 12, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.V.; Mehera, B. Effect of Bio-Fertilizers and Potassium on Growth and Yield of Maize (Zea mays L.). Pharma Innov. J. 2022, 11, 2348–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Khanghahi, M.Y.; Pirdashti, H.; Rahimian, H.; Nematzadeh, G.; Ghajar Sepanlou, M. Potassium Solubilising Bacteria (KSB) Isolated from Rice Paddy Soil: From Isolation, Identification to K Use Efficiency. Symbiosis 2018, 76, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, K.; Biswas, D.R.; Basak, B.B.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Biswas, S.; Das, T.K.; Agarwal, B.K. Exploring Waste Mica as an Alternative Potassium Source Using a Novel Potassium Solubilizing Bacterium and Rice Residue in K Deficient Alfisol. Plant Soil 2025, 509, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phares, C.A.; Amoakwah, E.; Danquah, A.; Afrifa, A.; Beyaw, L.R.; Frimpong, K.A. Biochar and NPK Fertilizer Co-Applied with Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) Enhanced Maize Grain Yield and Nutrient Use Efficiency of Inorganic Fertilizer. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Awad, M.Y.; Hegab, S.A.; Gawad, A.M.A.E.; Eissa, M.A. Effect of Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria (Bacillus cereus) on Growth and Yield of Potato. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 44, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuraja, R.; Muthukumar, T. Co-Inoculation of Halotolerant Potassium Solubilizing Bacillus licheniformis and Aspergillus violaceofuscus Improves Tomato Growth and Potassium Uptake in Different Soil Types under Salinity. Chemosphere 2022, 294, 133718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, E.; Pirdashti, H.; Lendeh, K.S. Phosphate and Potassium-Solubilizing Bacteria Effect on the Growth of Rice. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 103, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyalakshmi, B.; Ponmurugan, P.; Balamurugan, A. Potassium Solubilization and Plant Growth Promoting Substances by Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria (KSB) from Southern Indian Tea Plantation Soil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, H. Growth-Promoting Effect of Potassium-Solubilizing Microorganisms on Some Crop Species. In Potassium Solubilizing Microorganisms for Sustainable Agriculture; Meena, V., Maurya, B., Verma, J., Meena, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Shahzad, S.M.; Arif, M.S.; Yasmeen, T.; Ali, B.; Tanveer, A. Inoculation of Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria with Different Potassium Fertilization Sources Mediates Maize Growth and Productivity. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 57, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, S.P.; Maurya, B.R. Impact of Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria (KSB) and Sources of Potassium on Yield Attributes of Maize (Zea mays L.). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 1610–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Mandal, J.; Mandal, N.; Ghosh, M. Effect of Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria and Waste Mica on Potassium Uptake and Dynamics in Maize Rhizosphere. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci. 2020, 68, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.S.; Sundar, L.S.; Chao, Y.-Y. Foliar Application of Rhodopseudomonas palustris Enhances the Rice Crop Growth and Yield under Field Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, L.S.; Chang, Y.T.; Chao, Y.Y. Investigating the efficacy of purple non-sulfur bacteria (PNSB) inoculation on djulis (Chenopodium Formosanum Koidz.) growth, yield, and maturity period modulation. Plant Soil 2024, 496, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huu, T.N.; Giau, T.T.N.; Ngan, P.N.; Van, T.T.B.; Khuong, N.Q. Potential of phosphorus solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria isolated from acid sulfate soil in improving soil property, nutrient uptake, and yield of pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merrill) under acidic stress. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2022, 2022, 8693479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | pHH2O | pHKCl | EC | CEC | K+ | Na+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ |

| - | - | mS cm−1 | meq 100 g−1 | |||||

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 7.15 bc | 7.09 | 0.500 b | 17.2 | 0.428 bc | 0.140 abc | 12.3 | 2.28 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 7.13 c | 6.90 | 0.477 b | 17.1 | 0.423 bc | 0.153 a | 12.9 | 2.29 |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 7.16 bc | 6.92 | 0.455 bc | 17.8 | 0.427 bc | 0.133 bc | 12.2 | 2.30 |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 7.14 bc | 6.94 | 0.501 b | 17.4 | 0.432 bc | 0.146 ab | 12.2 | 2.31 |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 7.05 c | 6.85 | 0.470 b | 17.1 | 0.335 d | 0.128 cd | 12.7 | 2.30 |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 7.32 a | 6.95 | 0.400 d | 17.1 | 0.461 a | 0.105 e | 12.2 | 2.29 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 7.29 a | 7.02 | 0.370 d | 17.4 | 0.460 a | 0.109 e | 12.5 | 2.30 |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 7.31 a | 6.79 | 0.387 d | 18.0 | 0.463 a | 0.104 e | 12.2 | 2.31 |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 7.27 ab | 6.98 | 0.415 cd | 17.9 | 0.462 a | 0.109 e | 11.8 | 2.29 |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 7.16 bc | 6.85 | 0.363 d | 18.2 | 0.470 a | 0.090 f | 12.2 | 2.30 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 7.07 c | 6.76 | 0.717 a | 17.0 | 0.409 c | 0.116 de | 12.3 | 2.31 |

| FFP | 7.08 c | 6.80 | 0.500 b | 17.3 | 0.437 b | 0.128 cd | 12.5 | 2.32 |

| Significance | * | ns | * | ns | * | * | ns | ns |

| CV (%) | 1.14 | 2.72 | 7.26 | 5.31 | 3.29 | 7.78 | 4.55 | 0.73 |

| Treatment | OM | NH4+ | NO3− | Soluble P | Al-P | Fe-P | Ca-P | |

| %C | mg kg−1 | |||||||

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 1.13 | 7.33 c | 45.9 d | 123.6 c | 435.1 a | 548.8 ab | 151.3 abc | |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 1.12 | 7.44 c | 46.3 d | 112.5 d | 449.7 a | 552.1 a | 152.7 ab | |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 1.12 | 7.33 c | 46.8 d | 118.7 cd | 448.8 a | 531.9 b | 154.9 a | |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 1.16 | 7.36 c | 45.6 d | 110.3 d | 449.2 a | 536.3 ab | 158.4 a | |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 1.12 | 7.20 c | 45.5 d | 113.3 d | 451.9 a | 540.6 ab | 157.3 a | |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 1.18 | 8.45 ab | 61.2 a | 151.0 b | 336.4 c | 452.9 e | 127.9 ef | |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 1.19 | 8.57 a | 61.6 a | 149.8 b | 345.9 bc | 438.6 ef | 125.7 f | |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 1.16 | 8.49 ab | 61.4 a | 147.7 b | 361.6 b | 476.3 d | 139.3 cde | |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 1.14 | 8.33 ab | 62.0 a | 153.6 b | 341.0 c | 455.1 e | 127.0 ef | |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 1.16 | 7.99 b | 59.9 ab | 162.9 a | 342.5 bc | 429.6 g | 136.4 def | |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 1.09 | 7.01 c | 52.1 c | 113.9 d | 346.9 bc | 507.2 c | 142.2 bc | |

| FFP | 1.19 | 7.14 c | 57.9 b | 115.9 cd | 435.8 a | 553.4 a | 136.9 def | |

| Significance | ns | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| CV (%) | 10.5 | 4.39 | 3.91 | 4.52 | 3.14 | 2.24 | 5.68 | |

| Treatment | Dry Biomass (Tons ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Stems | Husks | Kernels | Cobs | |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 2.95 c | 2.58 e | 1.25 d | 9.85 e | 1.34 c |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 2.84 d | 2.54 ef | 1.14 e | 9.42 f | 1.29 cd |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 2.84 d | 2.52 ef | 1.14 e | 9.01 g | 1.27 d |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 2.71 e | 2.44 gh | 1.11 e | 8.97 g | 1.27 d |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 2.73 e | 2.39 h | 1.11 e | 8.95 g | 1.25 de |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 3.76 a | 3.33 a | 1.59 a | 11.7 a | 1.66 a |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 3.74 a | 3.35 a | 1.57 ab | 11.5 b | 1.62 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 3.74 a | 3.16 b | 1.54 bc | 11.3 c | 1.58 b |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 3.60 b | 2.97 c | 1.52 bc | 11.2 c | 1.59 b |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 3.55 b | 2.87 d | 1.51 c | 10.9 d | 1.56 b |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 2.81 d | 2.48 fg | 1.25 d | 9.73 e | 1.31 cd |

| FFP | 2.87 d | 2.49 fg | 1.14 e | 9.07 g | 1.20 e |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 1.59 | 1.75 | 2.46 | 0.93 | 2.75 |

| Treatment | Plant K Concentration (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Stems | Husks | Kernels | Cobs | |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 2.50 bc | 0.935 c | 0.736 cd | 0.705 cd | 0.376 b |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 2.54 b | 0.865 d | 0.713 d | 0.671 cde | 0.379 b |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 2.41 cd | 0.933 c | 0.668 e | 0.600 f | 0.371 b |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 2.39 cd | 0.816 e | 0.657 e | 0.613 f | 0.377 b |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 2.20 e | 0.708 g | 0.656 e | 0.596 f | 0.381 b |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 2.92 a | 1.02 a | 0.800 a | 0.812 a | 0.456 a |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 2.85 a | 1.01 a | 0.770 b | 0.811 a | 0.466 a |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 2.57 b | 1.04 a | 0.744 bc | 0.766 ab | 0.483 a |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 2.50 bc | 0.971 b | 0.725 cd | 0.711 bc | 0.467 a |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 2.47 bc | 0.752 f | 0.730 cd | 0.718 bc | 0.464 a |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 2.35 d | 0.756 f | 0.681 e | 0.651 def | 0.397 b |

| FFP | 2.05 f | 0.904 c | 0.653 e | 0.646 ef | 0.468 a |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 2.93 | 2.56 | 2.59 | 5.36 | 4.62 |

| Treatment | Plant K Uptake (kg ha−1) | Total K Uptake (kg ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Stems | Husks | Kernels | Cobs | ||

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 73.7 d | 24.1 c | 9.26 d | 69.4 d | 5.05 c | 181.5 e |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 72.4 de | 22.0 d | 8.13 ef | 63.1 de | 4.88 c | 170.4 f |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 68.4 ef | 23.5 cd | 7.64 fg | 54.1 f | 4.72 c | 158.3 gh |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 64.9 f | 19.9 e | 7.25 g | 55.0 f | 4.78 c | 151.8 h |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 60.0 g | 16.9 f | 7.26 g | 53.4 f | 4.77 c | 142.3 i |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 109.8 a | 33.9 a | 12.7 a | 95.1 a | 7.57 a | 259.1 a |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 106.7 a | 33.8 a | 12.1 b | 93.5 a | 7.53 a | 253.4 a |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 96.1 b | 32.7 a | 11.4 c | 86.5 b | 7.65 a | 234.4 b |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 89.9 c | 28.8 b | 11.0 c | 80.0 c | 7.42 a | 217.2 c |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 87.6 c | 21.6 d | 11.0 c | 78.4 c | 7.22 a | 205.8 d |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 66.1 f | 18.8 e | 8.54 e | 63.3 de | 5.19 bc | 161.9 g |

| FFP | 58.9 g | 22.4 dc | 7.43 g | 58.6 ef | 5.65 b | 153.1 h |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| CV (%) | 3.60 | 3.36 | 3.83 | 5.91 | 5.58 | 2.52 |

| Treatment | Plant Height | Ear Set Height | Stem Diameter | Leaf Length | Leaf Width | Ear Set Leaf Position | Green Leaf Number | Total Leaf Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | Leaves | |||||||

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 259.2 c | 101.6 bc | 1.19 b | 80.9 b | 8.36 b | 7.06 | 9.20 b | 13.5 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 252.6 de | 102.8 b | 1.15 b | 80.5 bc | 8.44 b | 7.43 | 9.15 b | 13.7 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 247.5 f | 102.0 bc | 1.13 b | 78.4 a | 8.40 b | 7.10 | 9.15 b | 13.0 bc |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 245.4 fg | 101.7 bc | 1.11 b | 78.5 a | 8.24 b | 7.00 | 9.30 b | 12.4 cd |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 241.6 h | 95.3 d | 1.02 c | 79.3 bc | 8.48 b | 7.15 | 9.40 b | 12.3 cd |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K+ LPS-PNSB | 265.5 a | 106.8 a | 1.34 a | 83.8 a | 9.39 a | 7.15 | 10.8 a | 13.6 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 261.8 b | 108.0 a | 1.34 a | 84.4 a | 9.35 a | 7.16 | 10.6 a | 14.1 a |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 254.2 d | 106.3 a | 1.33 a | 84.5 a | 9.34 a | 6.95 | 11.0 a | 13.5 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K+ LPS-PNSB | 247.1 fg | 107.4 a | 1.34 a | 83.6 a | 9.32 a | 7.20 | 10.5 a | 13.4 ab |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 244.7 f | 99.4 c | 1.10 b | 85.9 a | 9.12 a | 7.15 | 10.6 a | 12.1 d |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 251.4 e | 102.5 bc | 1.18 b | 80.9 b | 8.21 b | 7.47 | 9.40 b | 13.2 b |

| FFP | 250.8 e | 102.2 bc | 1.33 a | 81.3 b | 8.39 b | 7.10 | 9.30 b | 13.3 b |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | * | ns | * | * |

| CV (%) | 0.656 | 2.01 | 4.49 | 1.73 | 2.89 | 3.76 | 5.09 | 3.46 |

| Treatment | Ear Length | Ear Diameter | Number of Rows per Ear | Cob Length | Cob Diameter | Number of Kernels per Row | 100-Kernel Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | Rows | cm | Kernels | gram | |||

| 100%N-100%P-100%K | 17.5 bc | 3.70 a | 13.5 | 16.8 bc | 2.11 cdef | 36.4 d | 33.9 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K | 17.3 bc | 3.68 a | 13.3 | 16.4 c | 2.10 cdef | 36.1 d | 33.6 |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K | 16.8 cd | 3.38 b | 13.7 | 16.2 c | 2.06 efg | 36.6 d | 33.1 |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K | 16.5 d | 3.30 b | 12.8 | 16.1 c | 2.01 f | 36.4 d | 33.9 |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K | 15.6 e | 3.38 b | 13.3 | 15.3 c | 2.03 fg | 36.4 d | 33.3 |

| 100%N-100%P-100%K + LPS-PNSB | 18.7 a | 3.86 a | 13.5 | 18.1 a | 2.26 a | 39.6 a | 34.0 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + LPS-PNSB | 18.6 a | 3.83 a | 13.7 | 17.9 a | 2.21 ab | 38.8 ab | 34.8 |

| 100%N-100%P-50%K + LPS-PNSB | 18.9 a | 3.78 a | 13.4 | 18.0 a | 2.20 ab | 38.7 ab | 34.6 |

| 100%N-100%P-25%K + LPS-PNSB | 18.6 a | 3.84 a | 13.5 | 17.9 a | 2.17 bcd | 39.5 a | 33.1 |

| 100%N-100%P-0%K + LPS-PNSB | 18.4 a | 3.78 a | 14.0 | 18.2 a | 2.09 def | 38.4 abc | 33.7 |

| 100%N-100%P-75%K + CMI | 17.7 b | 3.76 a | 13.7 | 17.2 b | 2.14 bcde | 37.6 bcd | 33.1 |

| FFP | 16.9 cd | 3.77 a | 13.5 | 16.3 c | 2.18 abc | 37.0 cd | 33.2 |

| Significance | * | * | ns | * | * | * | ns |

| CV (%) | 2.37 | 3.17 | 5.69 | 2.45 | 2.44 | 2.58 | 2.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khuong, N.Q.; Quyen, L.K.; Nguyen, T.T.K.; Trong, N.D.; Thu, L.T.M.; Ngoc, V.Y.; Quang, L.T.; Thang, L.C.; Thao, P.T.P. Effect of K-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil K Content, Plant K Uptake, and Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in a Dyke Area in Field Conditions. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040137

Khuong NQ, Quyen LK, Nguyen TTK, Trong ND, Thu LTM, Ngoc VY, Quang LT, Thang LC, Thao PTP. Effect of K-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil K Content, Plant K Uptake, and Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in a Dyke Area in Field Conditions. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhuong, Nguyen Quoc, Ly Kim Quyen, Tran Trong Khoi Nguyen, Nguyen Duc Trong, Le Thi My Thu, Vo Yen Ngoc, Le Thanh Quang, La Cao Thang, and Pham Thi Phuong Thao. 2025. "Effect of K-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil K Content, Plant K Uptake, and Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in a Dyke Area in Field Conditions" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040137

APA StyleKhuong, N. Q., Quyen, L. K., Nguyen, T. T. K., Trong, N. D., Thu, L. T. M., Ngoc, V. Y., Quang, L. T., Thang, L. C., & Thao, P. T. P. (2025). Effect of K-Solubilizing Purple Nonsulfur Bacteria on Soil K Content, Plant K Uptake, and Yield of Hybrid Maize Grown on Alluvial Soil in a Dyke Area in Field Conditions. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040137