Antibiotic Susceptibility of Autochthonous Enterococcus Strain Biotypes Prevailing in Sheep Milk from Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Mild Thermization in View of Their Inclusion in a Complex Natural Cheese Starter Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sheep Milk Isolates, Reference-Control Strains, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Biochemical Identification and Biotyping of the Sheep Milk Isolates

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility of the Sheep Milk Isolates

3. Results

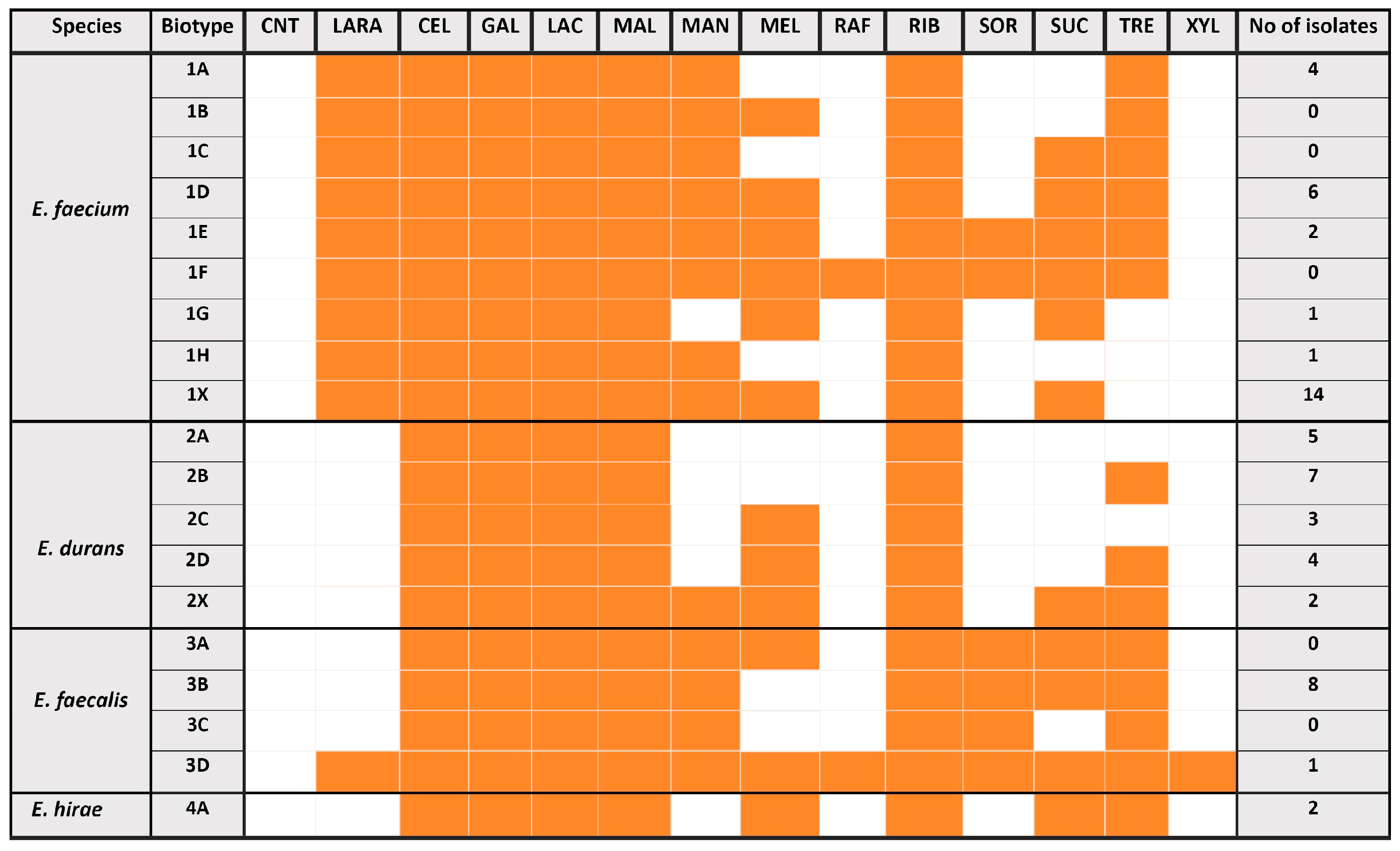

3.1. Comparative Species Identification and Biotyping of the Enterococcus Isolates Prevailing in Antilisterial Raw Milks and Surviving in the Same Milks After Thermization

3.2. Species-Dependent or Strain Biotype-Dependent Differences of the Enterococcus Sheep Milk Isolates in Their Enzymatic Activity Profiles

3.3. Antibiotic Resistances of the Enterococcus Species and Strain Biotypes Isolated from Sheep Milk of Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Thermization

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neviani, E.; Gatti, M.; Gardini, F.; Levante, A. Microbiota of cheese ecosystems: A perspective on cheesemaking. Foods 2025, 14, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, P.E.S.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Fernandez-Lopez, J.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Sayas-Barbera, M.E.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; Lorenzo, J.M. Autocthonous starter cultures in cheese production—A review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 5886–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, P.; Murphy, J.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D. Next-generation sequencing as an approach to dairy starter culture selection. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2015, 95, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, T.M.; Beresford, T.P.; Steele, J.; Broadbent, J.; Shah, N.P.; Ustunol, Z. Invited review: Advances in starter cultures and cultured foods. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4005–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, V.; Quero, G.M.; Poltronieri, P.; Morea, M.; Baruzzi, F. Autochthonous and probiotic lactic acid bacteria employed for production of “advanced traditional cheeses”. Foods 2019, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settanni, L.; Moschetti, G. Non-starter lactic acid bacteria used to improve cheese quality and provide health benefits. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Lactic acid bacteria in raw-milk cheeses: From starter cultures to probiotic functions. Foods 2022, 11, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujović, M.Z.; Mladenović, K.G.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T.; Laranjo, M.; Stefanović, O.D.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.D. Advantages and disadvantages of non-starter lactic acid bacteria from traditional fermented foods: Potential use as starters or probiotics. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1537–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E.; Tzanetakis, N. Chapter 9: The microfloras of traditional Greek cheeses. In Cheese and Microbes; Donnely, C.W., Ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vandera, E.; Kakouri, A.; Koukkou, A.-I.; Samelis, J. Major ecological shifts within the dominant nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in mature Greek Graviera cheese as affected by the starter culture type. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 290, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaș, H.; Çetin, B. Effects of novel autochthonous starter cultures on quality characteristics of yogurt. Int. J. Food Eng. 2024, 20, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Mucchetti, G. Invited review: Microbial evolution in raw-milk, long-ripened cheeses produced using undefined natural whey starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neviani, E. The natural whey starter used in the production of Grana Padano and Parmigiano Reggiano PDO cheeses: A complex microbial community. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callon, C.; Saubusse, M.; Didienne, R.; Buchin, S.; Montel, M.C. Simplification of a complex microbial antilisterial consortium to evaluate the contribution if its flora in uncooked pressed cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smid, E.J.; Erkus, O.; Spus, M.; Wolkers-Rooijackers, J.C.M.; Alexeeva, S.; Kleerebezem, M. Functional implications of the microbial community structure of undefined mesophilic starter cultures. Microbial Cell Fact. 2014, 13 (Suppl. S1), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, N.; Brdarić, E.; Dokić, J.; Dinić, M.; Veljović, K.; Golić, N.; Terzić-Vidojević, A. Yogurt produced by novel natural starter cultures improves gut epithelial barrier in vitro. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, L.; O’Sullivan, O.; Stanton, C.; Beresford, T.P.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D. The complex microbiota of raw milk. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 664–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Ricciardi, A.; Zotta, T. The microbiota of dairy milk: A review. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 107, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montel, M.C.; Buchin, S.; Mallet, A.; Delbés-Paus, C.; Vuitton, D.A.; Desmasures, N.; Berthier, F. Traditional cheeses: Rich and diverse microbiota with associated benefits. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 177, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzić-Vidojević, A.; Veljović, K.; Tolinački, M.; Živković, M.; Lukić, J.; Lozo, J.; Fira, Đ.; Jovčić, B.; Strahinić, I.; Begović, J.; et al. Diversity of non-starter lactic acid bacteria in autochthonous dairy products from Western Balkan countries—technological and probiotic properties. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Sadiq, F.A.; Burmølle, M.; Wang, N.I.; He, G.Q. Insights into psychrotrophic bacteria in raw milk: A review. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.N.; Van Doren, J.M.; Leonard, C.L.; Datta, A.R. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter spp. in raw milk in the United States between 2000 and 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.; Lee, S.; Choi, K.-H. Microbial benefits and risks of raw milk cheese. Food Control 2016, 63, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Barron, U.; Gonçalves-Tenório, A.; Rodrigues, V.; Cadavez, V. Foodborne pathogens in raw milk and cheese of sheep and goat origin: A meta-analysis approach. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 18, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilocca, B.; Costanzo, N.; Morittu, V.M.; Spina, A.A.; Soggiu, A.; Britti, D.; Roncada, P.; Piras, C. Milk microbiota: Characterization methods and role in cheese production. J. Proteom. 2020, 210, 103534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelis, J.; Lianou, A.; Kakouri, A.; Delbès, C.; Rogelj, I.; Matijašic, B.B.; Montel, M.C. Changes in the microbial composition of raw milk induced by thermization treatments applied prior to traditional Greek hard cheese processing. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianou, A.; Samelis, J. Addition to thermized milk of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris M104, a wild, novel nisin A–producing strain, replaces the natural antilisterial activity of the autochthonous raw milk microbiota reduced by thermization. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Dapkevicious, M.L.E.; Sgardioli, B.; Câmara, S.P.A.; Poeta, P.; Malcata, F.X. Current trends of enterococci in dairy products: A comprehensive review of their multiple roles. Foods 2021, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.; Stack, H.; Rea, R. Safety, beneficial and technological properties of enterococci for use in functional food applications—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3836–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkwirth, S.; Ayobami, O.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. Hospital-acquired infections caused by enterococci: A systematic review and meta-analysis, WHO European Region, 1 January 2010 to 4 February 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, S. The controversial nature of some non-starter lactic acid bacteria actively participating in cheese ripening. BioTech 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, T.J.; Gasson, M.J. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aun, E.; Kisand, V.; Laht, M.; Telling, K.; Kalmus, P.; Väli, Ü.; Brauer, A.; Remm, M.; Tenson, T. Molecular characterization of Enterococcus isolates from different sources in Estonia reveals potential transmission of resistance genes among different reservoirs. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 601490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Bortolaia, V.; Bover-Cid, S.; De Cesare, A.; Dohmen, W.; Guillier, L.; Jacxsens, L.; Nauta, M.; et al. Update of the list of qualified presumption of safety (QPS) recommended microbiological agents intentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA 21: Suitability of taxonomic units notified to EFSA until September 2024. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9169. [Google Scholar]

- Chessa, L.; Paba, A.; Dupré, I.; Daga, E.; Fozzi, M.C.; Comunian, R.A. A strategy for the recovery of raw ewe’s milk microbiodiversity to develop natural starter cultures for traditional foods. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelis, J.; Tsanasidou, C.; Bosnea, L.; Ntziadima, C.; Gatzias, I.; Kakouri, A.; Pappas, D. Pilot-scale production of traditional Galotyri PDO cheese from boiled ewes’ milk fermented with the aid of Greek indigenous Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris starter and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum adjunct strains. Fermentation 2023, 9, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Chessa, L.; Daga, E.; Dupré, I.; Paba, A.; Fozzi, M.C.; Dedola, D.G.; Comunian, R.A. Biodiversity and safety: Combination experimentation in undefined starter cultures for traditional dairy products. Fermentation 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glajzner, P.; Szewczyk, E.M.; Szemraj, M. Pathogenicity and drug resistance of animal streptococci responsible for human infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.P.; Luo, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Detection of antimicrobial resistance and virulence-related genes in Streptococcus uberis and Streptococcus parauberis isolated from clinical bovine mastitis cases in northwestern China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2784–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, A.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Shimamoto, T. Prevalence, antibiotic resistance and virulence of Enterococcus spp. in Egyptian fresh raw milk cheese. Food Control 2015, 50, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Pérez-Martín, F.; Seseña, S.; Palop, M.L. Seasonal diversity and safety evaluation of enterococci population from goat milk in a farm. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016, 96, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioziou, E.; Kakouri, A.; Bosnea, L.; Samelis, J. Antilisterial activity of raw sheep milk from two native Epirus breeds: Culture-dependent identification, bacteriocin gene detection and primary safety evaluation of the antagonistic LAB biota. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 6, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelis, J.; Bosnea, L.; Kakouri, A. Microbiological quality and safety of raw sheep milks from native Epirus breeds: Selective effects of thermization on the microbiota surviving in resultant thermized milks intended for traditional Greek hard cheese production. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandera, E.; Parapouli, M.; Kakouri, A.; Koukkou, A.I.; Hatziloukas, E.; Samelis, J. Structural enterocin gene profiles and mode of antilisterial activity in synthetic liquid media and skim milk of autochthonous Enterococcus spp. isolates from artisan Greek Graviera and Galotyri cheeses. Food Microbiol. 2020, 86, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsanasidou, C.; Asimakoula, S.; Sameli, N.; Fanitsios, C.; Vandera, E.; Bosnea, L.; Koukou, A.I.; Samelis, J. Safety evaluation, biogenic amine formation, and enzymatic activity profiles of autochthonous enterocin-producing Greek cheese isolates of the Enterococcus faecium/durans group. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.B.; Kopit, L.M.; Harris, L.J.; Marco, M.L. Draft genome sequence of the quality control strain Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6006–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švec, P.; Devriese, L.A. Genus I Enterococcus (ex Thiercelin and Jouhaud 1903) Schleifer and Klipper-Bälz 1984, 32VP. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, the Firmicutes, 2nd ed.; Whitman, W.B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 594–607. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 26th ed.; CLSI supplement M100S; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol Author Information; 2012 American Society for Microbiology, 1–13 December 2009. Available online: https://www.asm.org/Protocols/Kirby-Bauer-Disk-Diffusion-Susceptibility-Test-Pro (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- European Food Safety Authority. Guidance on the safety assessment of Enterococcus faecium in animal nutrition. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandera, E.; Tsirka, G.; Kakouri, A.; Koukkou, A.-I.; Samelis, J. Approaches for enhancing in situ detection of enterocin genes in thermized milk, and selective isolation of enterocin-producing Enterococcus faecium from Baird-Parker agar. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 281, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromou, K.; Thasitou, P.; Haritonidou, E.; Tzanetakis, N.; Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E. Microbiology of “Orinotyri”, a ewe’s milk cheese from the Greek mountains. Food Microbiol. 2001, 18, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.C.; Coelho, M.C.; Todorov, S.D.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Silva, C.C.G. Technological properties of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from Pico cheese an artisanal cow’s milk cheese. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 116, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B.T.; Svetlicic, E.; Zhao, S.; Berhane, N.; Jers, C.; Solem, C.; Mijakovic, I. Bad to the bone?—Genomic analysis of Enterococcus isolates from diverse environments reveals that most are safe and display potential as food fermentation microorganisms. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 283, 127702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.R.; Coburn, P.S.; Gilmore, M.S. Enterococcal cytolysin: A novel two component peptide system that serves as a bacterial defense against eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Curr. Prot. Pept. Sci. 2005, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos-Lopes, M.F.P.; Stanton, C.; Ross, P.R.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Silva, C.C.G. Genetic diversity, safety and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from artisanal Pico cheese. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugaban, J.I.I.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Todorov, S.D. Probiotic potential and safety assessment of bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus faecium strains with antibacterial activity against Listeria and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayobami, O.; Willrich, N.; Reuss, A.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. The ongoing challenge of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis in Europe: An epidemiological analysis of bloodstream infections. Emerg. Path. Infect. 2020, 9, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaro, L.; Basaglia, M.; Casella, S.; Hue, I.; Dousset, X.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Todorov, S.D. Bacteriocinogenic potential and safety evaluation of non-starter Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from home made white brine cheese. Food Microbiol. 2014, 38, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, L.L.; Semedo, T.; Tenreiro, R.; Crespo, M.T.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Malcata, F.X. Assessment of safety of enterococci isolated throughout traditional Terrincho cheesemaking: Virulence factors and antibiotic susceptibility. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, E.R.; Demirci, T.; Akin, N. In vitro assessment of probiotic and virulence potential of Enterococcus faecium strains derived from artisanal goatskin casing Tulum cheeses produced in central Taurus Mountains of Turkey. LWT 2021, 141, 110908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Omar, N.; Castro, A.; Lucas, R.; Abriouel, H.; Yousif, N.M.K.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Perez-Pulido, R.; Martinez-Canamero, M.; Galvez, A. Functional and safety aspects of enterococci isolated from different Spanish foods. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahansepas, A.; Sharifi, Y.; Aghazadeh, M.; Rezaee, M.A. Comparative analysis of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from clinical samples and traditional cheese types in the Northwest of Iran: Antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence traits. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuka, M.M.; Maksimovic, A.Z.; Tanuwidjaja, I.; Hulak, N.; Schloter, M. Characterization of enterococcal community isolated from an artisan Istrian raw milk cheese: Biotechnological and safety aspects. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 55, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, R.; Couto, N.; Marques, C.; Lopes, M.F.S.; Moschetti, G.; Pomba, C.; Settanni, L. Evaluation of antimicrobial resistance and virulence of enterococci from equipment surfaces, raw materials and traditional cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 236, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves de Sousa, M.; Muller, M.P.; Berghahn, E.; Volken de Souza, C.F.; Granada, C.E. New enterococci isolated from cheese whey derived from different animal sources: High biotechnological potential as starter cultures. LWT 2020, 131, 109808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, B.; Aktaș, H. Monitoring probiotic properties and safety evaluation of antilisterial Enterococcus faecium strains with cholesterol-lowering potential from raw cow’s milk. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, S.; Silvetti, T.; Miranda Lopez, J.M.; Brasca, M. Antimicrobial activity, antibiotic resistance and the safety of lactic acid bacteria in raw milk Valtellina Casera cheese. J. Food Saf. 2015, 35, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić-Vidojević, A.; Veljović, K.; Begović, J.; Filipić, B.; Popović, D.; Tolinački, M.; Miljković, M.; Kojić, M.; Golić, N. Diversity and antibiotic susceptibility of autochthonous dairy enterococci isolates: Are they safe candidates for autochthonous starter cultures? Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; RASFF Window. Notification 2024.6538: Listeria monocytogenes in Cheese from Italy. Sheep’s Milk Cheese (Ripe Semi Hard Sheep’s Cheese) from Italy. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/screen/notification/708144 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Food Safety News. Sheep Cheese Recalled Because of Listeria. Available online: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2023/07/sheep-cheese-recalled-because-of-listeria/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. Goot Essa Recalls der Mutterschaft Cheese Because of Possible Health Risk—Potential Contamination with Listeria monocytogenes. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gérard, A.; El-Hajjaji, S.; Niyonzima, E.; Daube, G.; Sindic, M. Prevalence and survival of Listeria monocytogenes in various types of cheese—A review. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2018, 71, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rios, V.; Dalgaard, P. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in European cheeses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Control 2018, 84, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameli, N.; Skandamis, P.N.; Samelis, J. Application of Enterococcus faecium KE82, an enterocin A-B-P-producing strain, as an adjunct culture enhances inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes during traditional protected designation of origin Galotyri processing. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U. Mild heat treatment and biopreservatives for artisanal raw milk cheeses: Reducing microbial spoilage and extending shelf-life through thermisation, plant extracts and lactic acid bacteria. Foods 2023, 12, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | No of Isolates | Molecular Id-Method/s | Antilisterial Enterocin Activity | Safety Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M17 agar Overlay 2 | CFS/Well Assay 2 | Bac-gene/s Possessed 3 | Hemolytic Activity | Cytolysin vanA/vanB | Virulence gene/s 4 | |||

| Enterococcus faecium | 6 | IGS/16S rRNA | ++ (3) + (3) | ++ (3) ng (3) | entA/entB/entP (3) entA (3) | A | No/No | None |

| Enterococcus durans | 9 | IGS/16S rRNA | + (1) +w (2) ng (6) | ng (9) | entA/entP (1) entP (2) None (6) | A | No/No | None |

| Enterococcus hirae | 1 | IGS/16S rRNA | +w (1) | ng (1) | entA (1) | A | No/No | None |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3 | IGS | ng (3) | ng (3) | None | A | No/No | ace/gelE (1) ace (1), gelE (1) |

| Species | Biotype | RM Isolates | TM Isolates | Total Isolates | Isolate Code Number 1 | Reference Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococccus faecium | 1A | 3 | 1 | 4 | KFM17 **, KFM28 **, KFM29 **, KTM21 | KE118 ** |

| 1D | 6 | 6 | KTM46 **, KTM47 **, KTM50, KTM53, KTM54, KTM55 ** | KE82 **, KE85 | ||

| 1E | 2 | 2 | KTM20, KTM37 | KE86 | ||

| 1G | 1 | 1 | KTM7 | |||

| 1H | 1 | 1 | KTM49 ** | KE118 ** (1A/1H) | ||

| 1X | 3 | 11 | 14 | KFM57 *, KFM58 *, KFM59 *, KTM3, KTM6, KTM10, KTM11, KTM12, KTM32, KTM33, KTM36, KTM40, KTM41, KTM52 | KE77 * | |

| Enterococcus durans | 2A | 5 | 5 | KTM19, KTM25, KTM38, KTM45 *, KTM48 * | KE100 * | |

| 2B | 5 | 2 | 7 | KFM16, KFM18, KFM20, KFM27, KFM30, KTM24, KTM31 * | KE108 * | |

| 2C | 2 | 1 | 3 | KFM6 *, KFM19, KTM17 | KE106 | |

| 2D | 4 | 4 | KTM23, KTM42, KTM43, KTM44 | KE66 | ||

| 2X | 2 | 2 | KFM46 *, KFM49 * | |||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3B | 2 | 6 | 8 | KFM47, KFM50, KTM13, KTM22, KTM34 *, KTM35 *, KTM39, KTM51 | GL322 * |

| 3D | 1 | 1 | KFM48 | |||

| Enterococcus hirae | 4A | 1 | 1 | 2 | KFM56 *, KTM4 |

| Species | Biotype | M17 Agar Overlay 1 | CFS/Well Assay 2,3 | Enterocin Gene/s Detected by PCR 4,5 | Sheep Milk Isolates with the Same Ent+ Profile 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entA | entB | entP | bac31 | |||||

| E. faecium | 1A | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | KFM17, KFM28, KFM29 |

| 1D | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | KTM46, KTM47 | |

| 1D | ++ | ++ | + | − | − | − | KTM55 | |

| 1H | ++ | ++ | + | + | − | − | KTM49 | |

| 1X | + | − | + | − | − | − | KFM57, KFM58, KFM59 | |

| E. durans | 2A | + | − | − | − | + | − | KTM45, KTM48 |

| 2B | + | − | + | − | + | + | KTM31 | |

| 2C | + | − | + | − | + | − | KFM6 | |

| 2X | (+) | − | − | − | + | − | KFM46, KFM49 | |

| E. faecalis | 3B | + | − | − | − | − | − | KTM34, KTM35 |

| E. hirae | 4A | (+)/− | − | + | − | − | − | KFM56 |

| Test | Reaction/Enzymes | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus hirae | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | 1G | 1H | 1X | 3B | 4A | ||

| VP | Acetoin production | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| HIP | Hydrolysis (Hipuric acid) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ESC | β-glucosidase hydrolysis | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| PYRA | Pyrolidonyl arylamidase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| αGAL | α-galactosidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| βGUR | β-glucuronidase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| βGAL | β-galactosidase | + | + | + | +/− * | − | + |

| PAL | Alkaline phosphatase | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LAP | Leucine aminopeptidase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ADH | Arginine dihydrolase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RIB | D-ribose (acidification) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ARA | L-arabinose (acidification) | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| MAN | D-mannitol (acidification) | + | − | + | +/(+) | + | − |

| SOR | D-sorbitol (acidification) | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| LAC | D-lactose (acidification) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| TRE | D-trehalose (acidification) | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| INU | Inulin (acidification) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RAF | D-raffinose (acidification) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AMD | Starch (acidification) | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| GLYG | Glycogen (acidification) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| βHEM | β-hemolysis | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| API code | 5157510 | 5157400 | 5157500 | 5157500 5147500 * | 1143711 | 5153410 | |

| API-ID | E. faecium 1 Very good | E. durans Good | E. faecium Good | E. faecium Good | E. faecalis Good | E. durans Good | |

| Species | Biotype | Enzymes Tested 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | ||

| E. faecium | ||||||||||||||||||||

| KE 118 ** | 1A | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KFM 28 ** | 20 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KFM 29 ** | 10 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 10 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KE 64 ** | 1B | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KE 85 | 1D | 20 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KE 82 ** | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 46 ** | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 47 ** | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 54 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 55 ** | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 20 | 40 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 37 | 1E | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 7 | 1G | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 10 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 49 ** | 1H | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KE 77 * | 1X | 30 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 32 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KFM 57 * | 0 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KFM 58 * | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E. durans | ||||||||||||||||||||

| KE 100 * | 2A | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 45 * | 20 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 48 * | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KE 108 * | 2B | 20 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KFM 20 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 31 * | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KFM 6 * | 2C | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 42 | 2D | 5 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KFM 46 * | 2X | 10 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KFM 49 * | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E. faecalis | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GL 322 * | 3B | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM 34 * | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 35 * | 20 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 39 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KTM 51 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GL 320 ** | 3C | 10 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KFM 48 | 3D | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. hirae | ||||||||||||||||||||

| KFM 56 * | 4A | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strain Code (Biotype) | Antibiotic Tested (μg/Disk) 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP 10 | CHL 30 | CIP 5 | ERY 15 | GEN 10 | PEN10U | TET 30 | VAN 30 | |

| Control Strains | ||||||||

| E. faecium 315VR ** (1F) | R (6.0) | I (16.1) | R (6.0) | R (6.0) | R (6.0) | R (6.0) | R (9.4) | R (7.6) |

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212TM | S (20.6) | S (22.0) | I (19.1) | I (16.8) | I (9.4) | R (12.7) | I (15.1) | I (16.1) |

| E. faecalis GL320 ** (3C) (virulent, β-hemolytic) | S (22.8) | S (26.2) | I (19.1) | I (21.5) | S (11.8) | R (12.6) | S (26.9) | I (16.1) |

| E. faecalis GL322 * (3B) (control, non-virulent) | S (26.2) | S (22.2) | I (15.8) | I (19.8) | NT | S (17.6) | S (24.5) | R (12.3) |

| Sheep milk isolates | ||||||||

| E. faecalis KFM47 (3B) | S (19.5) | S (21.8) | I (16.6) | I (16.9) | R (6.5) | R (9.2) | R (9.7) | I (15.7) |

| E. faecalis KFM50 (3B) | S (19.4) | S (24.2) | I (19.0) | S (22.7) | S (10.3) | R (13.3) | S (30.1) | I (16.3) |

| E. faecalis KTM13 (3B) | S (22.5) | S (23.0) | S (22.0) | I (20.9) | I (8.0) | R (12.1) | S (26.6) | I (16.4) |

| E. faecalis KTM22 (3B) | S (23.3) | S (23.2) | S (20.0) | I (19.4) | I (7.7) | R (10.7) | S (25.9) | R (13.9) |

| E. faecalis KTM34 * (3B) | S (22.5) | S (22.5) | I (17.5) | I (19.8) | I (7.9) | R (11.2) | S (27.7) | R (13.9) |

| E. faecalis KTM35 * (3B) | S (20.4) | S (22.8) | I (17.8) | I (19.4) | I (7.6) | R (13.3) | S (26.3) | R (14.2) |

| E. faecalis KTM39 (3B) | R (14.4) | S (24.9) | I (19.1) | S (24.5) | S (11.3) | R (13.3) | S (30.0) | I (15.7) |

| E. faecalis KTM51 (3B) | S (19.1) | S (27.7) | I (18.4) | S (25.7) | I (9.2) | R (8.6) | S (32.0) | S (16.8) |

| E. faecalis KFM48 (3D) | S (18.0) | S (22.0) | I (19.2) | I (20.2) | S (11.5) | R (8.3) | S (19.6) | S (16.9) |

| E. hirae KFM56 * (4A) | S (18.7) | S (23.5) | S (22.7) | I (21.4) | I (8.4) | R (12.0) | S (24.8) | R (13.4) |

| E. hirae KTM4 (4A) | S (21.0) | S (23.9) | I (19.8) | I (21.2) | S (12.5) | S (16.2) | S (26.2) | S (17.9) |

| Strain (Isolate) | Antibiotic Tested (μg/Disk) 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP 10 | CHL 30 | CIP 5 | ERY 15 | GEN 10 | PEN10U | TET 30 | VAN 30 | |

| Biotype 1A | ||||||||

| E. faecium KE118 ** (control; 1A/1H) | S (17.0) | S (22.7) | R (13.0) | R (12.7) | S (11.6) | S (14.5) | S (25.9) | S (18.6) |

| E. faecium KFM17 ** | R (14.7) | S (21.8) | I (17.5) | R (13.5) | S (12.8) | R (10.1) | S (25.6) | S (18.1) |

| E. faecium KFM28 ** | R (16.5) | S (24.4) | I (16.7) | R (9.2) | S (13.5) | R (7.6) | S (31.9) | S (21.1) |

| E. faecium KFM29 ** | S (17.2) | S (24.9) | I (16.8) | I (14.1) | S (11.5) | R (9.8) | S (25.8) | S (19.5) |

| E. faecium KTM21 | S (24.3) | S (21.2) | I (17.6) | I (21.1) | S (12.5) | S (19.3) | S (24.5) | S (17.2) |

| Biotype 1D | ||||||||

| E. faecium KE82 ** (control) | S (17.3) | S (24.9) | R (12.0) | R (11.0) | S (11.3) | R (11.3) | S (28.3) | S (19.4) |

| E. faecium KE85 (control) | S (20.8) | S (25.7) | R (13.3) | I (16.5) | I (8.1) | R (12.2) | R (10.3) | S (21.4) |

| E. faecium KTM46 ** | R (13.8) | S (29.0) | R (13.6) | R (9.9) | S (11.5) | R (8.9) | S (25.5) | S (20.0) |

| E. faecium KTM47 ** | R (13.8) | S (27.3) | R (14.9) | R (11.0) | S (12.0) | R (7.5) | S (27.6) | S (19.6) |

| Four remaining E. faecium 1D isolates | S (20.5 ± 2.0) | S (23.3 ± 1.7) | I (17.1 ± 1.3) | I (20.0 ± 1.3) | S (12.3 ± 1.6) | S (18.3 ± 1.1) | S (27.0 ± 1.7) | S (18.3 ± 0.8) |

| Biotype 1E | ||||||||

| E. faecium KTM37 | S (19.7) | S (23.9) | I (16.6) | R (13.1) | S (12.5) | S (27.5) | S (27.8) | S (21.4) |

| E. faecium KTM20 | S (20.8) | S (23.3) | S (21.2) | I (21.9) | S (13.2) | S (16.0) | S (26.0) | S (18.3) |

| Biotype 1G | ||||||||

| E. faecium KTM7 | S (22.9) | S (23.7) | I (16.7) | I (14.6) | S (12.0) | S (25.1) | S (26.9) | S (17.8) |

| Biotype 1H | ||||||||

| E. faecium KTM49 ** | S (22.7) | S (21.5) | R (13.3) | R (11.2) | S (10.5) | S (22.0) | S (26.2) | S (19.2) |

| Biotype 1X | ||||||||

| E. faecium KE77 * (control) | S (26.4) | S (25.5) | I (18.2) | I (18.5) | S (14.4) | S (22.8) | S (28.1) | S (19.8) |

| All 14 sheep milk isolates | S (21.4 ± 2.7) | S (25.8 ± 2.2) | I (18.2 ± 1.7) | I (20.1 ± 3.5) | S (13.5 ± 1.3) | S (20.6 ± 3.5) | S (28.4 ± 3.5) | S (19.8 ± 1.9) |

| Strain (Isolate) | Antibiotic Tested (μg/Disk) 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP 10 | CHL 30 | CIP 5 | ERY 15 | GEN 10 | PEN10U | TET 30 | VAN 30 | |

| Biotype 2A | ||||||||

| E. durans KE100 * (control) | S (20.0) | S (21.7) | I (20.4) | I (20.9) | S (10.7) | S (17.1) | S (23.0) | S (18.0) |

| E. durans KTM19 | S (23.1) | S (23.4) | S (22.5) | S (23.6) | S (16.0) | R (14.3) | S (29.3) | S (18.9) |

| E. durans KTM38 | S (20.3) | S (23.4) | S (22.3) | R (10.5) | S (13.9) | R (13.3) | S (24.9) | S (18.4) |

| Three remaining E. durans 2A isolates | S (21.2 ± 1.4) | S (22.3 ± 1.2) | S (21.2 ± 1.7) | S (22.1 ± 2.1) | S (12.3 ± 3.3) | S (16.9 ± 1.7) | S (24.2 ± 2.7) | S (19.2 ± 2.0) |

| Biotype 2B | ||||||||

| E. durans KE108 * (control) | S (23.4) | S (26.9) | I (19.8) | S (24.0) | S (10.2) | S (19.3) | S (24.0) | S (19.0) |

| E. durans KFM16 | S (19.8) | S (25.0) | S (23.2) | S (23.6) | S (13.4) | R (14.2) | S (27.0) | S (19.0) |

| E. durans KFM18 | S (21.0) | S (25.7) | S (24.0) | S (24.2) | S (13.5) | R (13.0) | S (30.0) | S (19.9) |

| E. durans KFM20 | S (20.2) | S (23.9) | S (24.2) | S (24.8) | S (13.4) | R (14.5) | S (26.8) | S (20.5) |

| E. durans KTM24 | S (19.6) | S (21.4) | I (20.1) | S (23.5) | S (11.2) | R (13.7) | S (26.8) | S (19.4) |

| Three remaining E. durans 2B isolates | S (21.3 ± 2.5) | S (24.9 ± 2.1) | S (21.7 ± 1.8) | S (23.5 ± 1.2) | S (11.8 ± 2.7) | S (17.2 ± 2.2) | S (25.8 ± 2.5) | S (20.2 ± 0.8) |

| Biotype 2C | ||||||||

| E. durans KFM6 * | R (15.9) | S (25.1) | S (22.3) | R (7.8) | S (14.7) | S (17.7) | S (32.8) | S (21.8) |

| E. durans KFM19 | R (16.1) | S (23.7) | I (18.4) | S (23.7) | S (12.4) | R (10.6) | S (25.9) | S (19.5) |

| E. durans KTM17 | S (20.3) | S (22.5) | S (22.6) | I (20.2) | S (12.1) | R (13.8) | S (25.6) | S (17.5) |

| Biotype 2D | ||||||||

| E. durans KTM44 | S (18.0) | S (25.9) | S (24.3) | S (23.5) | S (13.8) | R (13.8) | S (26.8) | S (17.9) |

| Three remaining E. durans 2D isolates | S (18.4 ± 1.2) | S (24.9 ± 1.7) | S (22.5 ± 1.1) | S (24.7 ± 1.9) | S (14.8 ± 1.6) | S (15.5 ± 0.5) | S (25.1 ± 1.9) | S (18.2 ± 0.9) |

| Biotype 2X | ||||||||

| E. durans KFM46 * | S (23.7) | S (23.7) | S (21.5) | S (23.4) | S (13.1) | S (16.4) | R (13.0) | S (19.4) |

| E. durans KFM49 * | S (23.6) | S (21.7) | S (24.5) | S (24.5) | S (14.5) | R (13.9) | R (12.0) | S (20.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samelis, J.; Kakouri, A. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Autochthonous Enterococcus Strain Biotypes Prevailing in Sheep Milk from Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Mild Thermization in View of Their Inclusion in a Complex Natural Cheese Starter Culture. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040125

Samelis J, Kakouri A. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Autochthonous Enterococcus Strain Biotypes Prevailing in Sheep Milk from Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Mild Thermization in View of Their Inclusion in a Complex Natural Cheese Starter Culture. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040125

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamelis, John, and Athanasia Kakouri. 2025. "Antibiotic Susceptibility of Autochthonous Enterococcus Strain Biotypes Prevailing in Sheep Milk from Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Mild Thermization in View of Their Inclusion in a Complex Natural Cheese Starter Culture" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040125

APA StyleSamelis, J., & Kakouri, A. (2025). Antibiotic Susceptibility of Autochthonous Enterococcus Strain Biotypes Prevailing in Sheep Milk from Native Epirus Breeds Before and After Mild Thermization in View of Their Inclusion in a Complex Natural Cheese Starter Culture. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040125