1. Introduction

Traffic congestion and connectivity problems in Quito significantly affect the quality of life of its inhabitants. The Quito Metro emerges as a solution to improve urban mobility, but its success will depend on strategies that integrate other modes of transport, such as bicycles [

1]. This study explores the potential of bicycles as a complement to the metro to reduce travel times and promote a sustainable mobility model [

2].

Urban mobility and traffic congestion are critical challenges facing large cities globally. The accelerated growth of the urban population and the expansion of the vehicle fleet have generated a significant increase in traffic levels, affecting the quality of life of the inhabitants and the economic efficiency of the metropolises [

3]. According to a World Bank report, congestion in cities can reduce urban productivity by 2% to 5% of GDP, due to wasted time and increased operating costs [

4].

In addition, the World Health Organization highlights that air pollution, exacerbated by vehicular traffic, is responsible for approximately 4.2 million premature deaths per year, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable solutions in urban transport [

5].

These problems show the importance of implementing efficient and sustainable public transport systems that mitigate the negative effects of congestion in large cities [

6].

Quito, the capital of Ecuador, has an estimated population of approximately 2.8 million people (2023). This demographic context is important for understanding the scale of the mobility challenges and the potential impact of the Quito Metro on urban transportation [

7].

The city of Quito faces a critical problem of urban mobility due to its accelerated population growth and a road infrastructure that has not evolved at the same pace. Traffic congestion is one of the main concerns of Quito’s residents, generating long travel times, high levels of pollution and a negative impact on the quality of life of its inhabitants [

7]. Added to this is the reliance on traditional public transport systems, such as buses, trolleybuses and eco-roads, which operate with limited frequency and are often saturated at peak times [

8].

In this context, the Quito Metro emerges as a strategic solution to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce travel times and promote a sustainable mobility model [

7]. This project, the first of its kind in the city, promises to transform the way citizens get around, connecting different parts of the capital more efficiently and complementing existing transport systems.

The main goal of the Quito Metro is to offer an efficient, fast and reliable transport system, capable of meeting the growing demand for mobility in an expanding city. Its specific objectives include: efficiency in urban mobility, environmental sustainability, accessibility and inclusion, and positive economic impact [

9].

The Quito Metro is a 22-km underground system with 15 stations, officially inaugurated in 2023. Designed to alleviate congestion, it operates at 4-min intervals during peak hours and is expected to serve over 400,000 passengers daily [

9].

The objective of the study is to evaluate the potential impact of the integration of bicycles as a complementary mode to the Quito Metro system, identifying key strategies to improve connectivity, reduce travel times and encourage the adoption of the system in peripheral areas with significant access barriers.

2. State of the Art

Urban mobility faces important challenges in the current context of population growth and accelerated urbanization, highlighting traffic congestion, environmental pollution and the need for sustainable transport systems. In this context, micromobility, particularly the use of bicycles, has emerged as a complementary and efficient solution to improve connectivity in cities.

2.1. Micromobility as an Urban Solution

The adoption of bicycles as a means of transport in cities has demonstrated numerous benefits in terms of mobility and sustainability. Cities such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen lead in infrastructure and massive use of bicycles, significantly reducing carbon emissions and improving the quality of life of their inhabitants [

10]. In addition, recent studies have shown that the incorporation of bicycles in urban transport systems can reduce travel times, promote social inclusion and facilitate access to basic services [

11].

A report by the [

12]. He highlights that micromobility has a positive impact on the “first and last mile” of urban transport, solving problems of access to mass transport stations. This effect has been particularly evident in cities in Latin America, where bicycles have helped mitigate connectivity problems in peripheral areas [

13].

2.2. Integration of Bicycles with Mass Transportation Systems

One of the main challenges in integrating mass transit systems with bicycles is the efficient planning of infrastructure and urban logistics. In this sense, the work of [

14]. It emphasizes the importance of a holistic approach in transportation network design, highlighting how intermodality can optimize mobility and reduce traffic congestion. This approach is particularly relevant for cities such as Quito, where the lack of connectivity between different modes of transport limits the efficiency of the mobility system. The implementation of strategies that encourage the combined use of bicycles and the metro requires a logistical design that minimises access barriers and guarantees the safety of users on first and last mile journeys.

Several mass transit systems have successfully implemented modal integration strategies with bicycles. For example, the Medellín Metro in Colombia complements its service with bike lanes connected to stations and bike-sharing programs. This has made it possible to increase accessibility and reduce travel times in the most remote areas [

15]. Similarly, cities such as Berlin and Shenzhen have integrated fare systems that allow users to combine public transport and bicycles through single tickets, which has increased the adoption of micromobility [

16].

Studies also highlight that secure cycling infrastructure is a key factor for the success of modal integration. In the Netherlands, the design of cycle lanes separated from vehicular traffic and the availability of secure parking at train stations have significantly increased the use of bicycles as a means of access [

17].

2.3. Barriers to Implementation

Despite the benefits, the implementation of intermodal transport systems faces significant barriers. The lack of adequate cycling infrastructure, such as safe bike lanes and bike racks, represents a significant obstacle to their adoption [

18]. In addition, the perception of road insecurity and the risk of bicycle theft are factors that discourage their use, especially in low- and middle-income cities [

19].

Another crucial factor for the adoption of intermodal mobility systems is road safety on cycle routes. According to [

20], the analysis of the frequency of accidents in urban environments using Bayesian networks allows the identification of risk patterns and the optimization of mitigation strategies. This perspective is essential when evaluating the integration of bicycles with the Quito Metro, since the perception of insecurity is a key barrier that discourages the use of bicycles as a complement to public transport. The implementation of protected bike lanes and the development of road awareness programs can significantly reduce accidents and encourage greater adoption of micromobility in the city.

In the context of Latin America, the cost of tariffs and the lack of subsidies for vulnerable users also limit the expansion of these systems [

21]. Therefore, it is essential to design inclusive strategies to overcome these barriers and encourage greater use of bicycles as a complement to mass transport.

2.4. Impacts of Micromobility in Latin American Cities

The positive impact of modal integration has been evidenced in cities such as Santiago de Chile, where the public bicycle system “Bike Santiago” connects with metro lines, reducing travel times by an average of 20% [

22]. Similarly, in Bogotá, the TransMilenio has implemented bicycle feeder routes that have improved access from the peripheries to the mass system, encouraging the use of sustainable transport [

23].

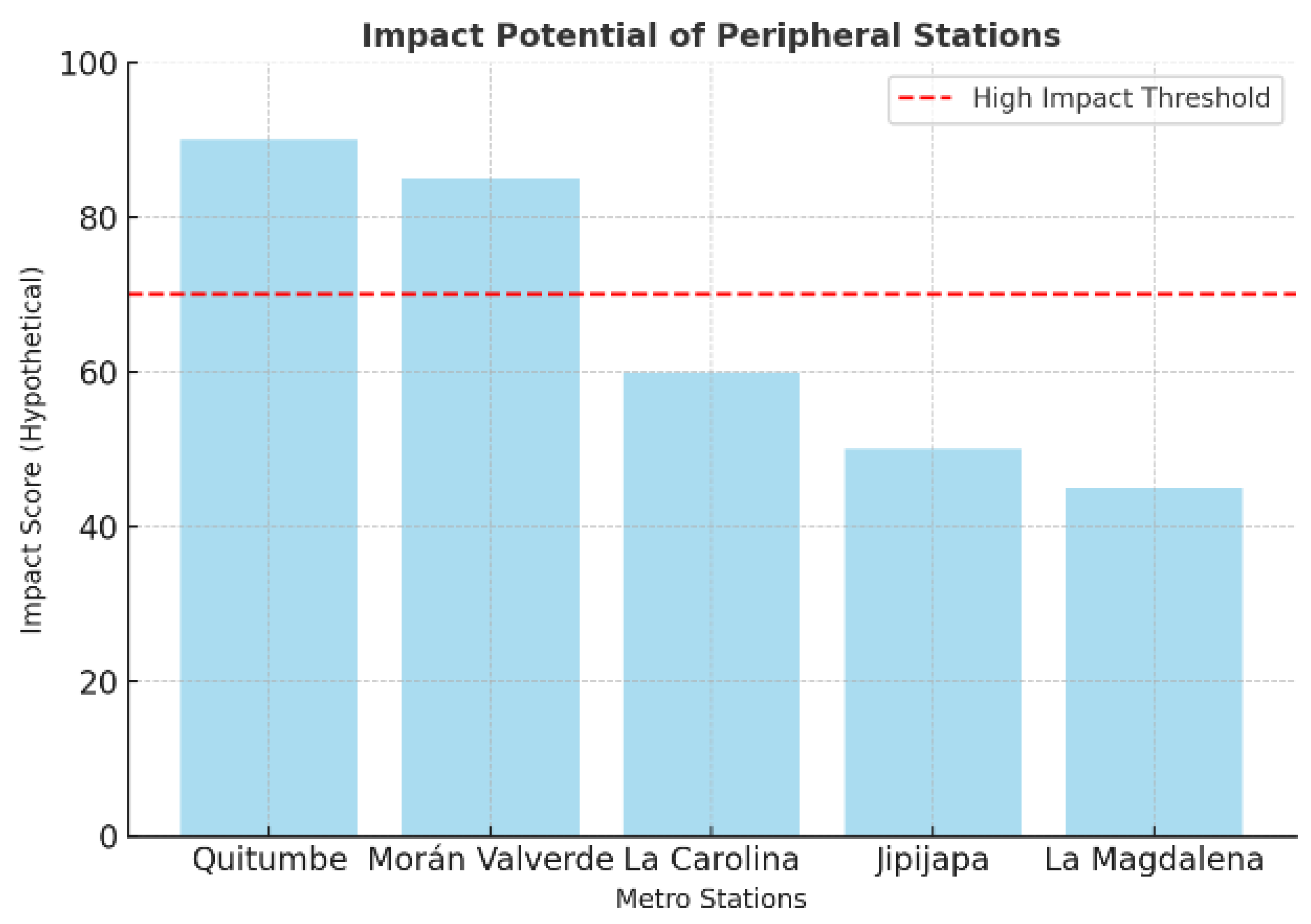

In Quito, the connectivity problem is especially relevant in peripheral stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, where the lack of intermodal infrastructure limits the potential of the Quito Metro as a comprehensive urban mobility solution. This study seeks to contribute to the analysis and proposals of strategies to overcome these barriers, based on the lessons learned from international cases [

24].

2.5. Gap in Research

The analysis of the state of knowledge shows that, although there are successful experiences in the integration of bicycles with mass transport systems in cities such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Medellín and Bogotá, in the case of Quito this strategy has not yet been explored in depth. Despite the documented benefits in reducing travel times and increasing the adoption of public transport, the literature on urban mobility in Quito has focused mainly on the operational efficiency of the Metro and traffic congestion, without specifically considering micromobility as a strategic complement. Likewise, the lack of studies that evaluate the real impact of cycling infrastructure and the necessary conditions for its implementation in key stations, such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, represents a knowledge gap in sustainable transport planning in the city.

This study seeks to fill this gap by empirically analyzing the potential for integration between bicycles and the Quito Metro, based on data collected from current and potential users of the system. Unlike previous research that has addressed mobility from a general perspective, this research provides a specific focus on connectivity barriers in peripheral stations and proposes concrete strategies to overcome them. In addition, scenario simulation allows quantifying the possible time savings that micromobility could generate, offering evidence for the formulation of public policies aimed at improving accessibility and promoting the use of the metro. In this way, the study not only contributes to academic knowledge in urban mobility, but also provides practical tools for the planning and management of transport in Quito.

Unlike previous studies, this research offers a combined methodological and spatial approach that integrates perception data, access-time simulations, and station-level prioritization, offering replicable tools for micromobility planning in emerging cities.

3. Methodology

The methodology developed by the research is structured in 3 large blocks (

Figure 1):

The research methodology was structured in three consecutive phases, as summarized in

Figure 1.

To generate the work scenario, a structured questionnaire was designed and distributed digitally using Google Forms during a two-week period in February 2023. The survey aimed to capture key information including user perceptions about the Quito Metro’s ability to alleviate traffic congestion, current connectivity to metro stations, average travel times, expected time savings when using the metro, willingness to combine bicycles with the metro system, and opinions on proposed fare levels.

The target population consisted of students from the Central University of Ecuador (UCE), whose campus is located near several metro stations. A total of 522 valid responses were collected using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling approach. This population was selected due to their high potential to adopt multimodal commuting patterns and their relevance as young, frequent users of public transport.

Survey Design and Participants: the survey was administered to students of the Central University of Ecuador (UCE), a group representing the target population for this study. The questionnaire was distributed digitally via Google Forms, targeting 522 valid responses. The sample was selected using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling approach, meaning that respondents were selected based on availability. The survey was distributed through institutional channels, ensuring that only UCE students participated.

The survey used a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method, which means that participants were selected based on convenience rather than random selection. The sample consisted of students from the Central University of Ecuador (UCE), a group that was easily accessible and representative of urban commuters who use public transportation frequently. The survey was distributed through official UCE channels, including institutional emails and student groups on social media, to ensure that only UCE students participated.

Although this sample is not fully representative of the entire population of Quito, it provides valuable insights into mobility patterns among young urban commuters who are likely to adopt metro and bicycle use.

Future studies can benefit from a more diverse sample to strengthen the generalizability of the findings.

The survey conducted in this study included various questions aimed at assessing the feasibility and potential benefits of integrating bicycles with the Quito Metro system. Below are some of the key questions relevant to this study (

Table 1):

Once the data was collected, it underwent a cleaning process to eliminate incomplete or inconsistent entries. Responses were coded thematically to identify recurring barriers and perceptions related to micromobility. Descriptive statistical techniques were applied to explore trends in the dataset, including frequency distributions, percentage comparisons, and cross-tabulations.

Simulations were then developed to estimate the potential time savings achieved by integrating bicycles as a first- and last-mile solution. A 30% reduction in access times was modeled, based on literature benchmarks. These simulations allowed for comparative analysis between current and projected conditions across metro stations, helping to identify those with the greatest potential for improvement.

The 30% reduction was used to model a best-case scenario, where bicycles are adopted as a first- and last-mile solution to improve access to the metro stations. The modeling assumes that cyclists will experience a direct route to stations, avoiding congestion and other barriers.

The 30% reduction in access time is an estimated value derived from literature benchmarks that suggest bicycle integration can lead to significant reductions in travel time, particularly in first- and last-mile commuting scenarios (e.g., ITDP International Transport Development Program (ITDP), 2018). This value was applied to average reported travel times from survey respondents to model the potential impact of bicycles on reducing access times to metro stations.

To prioritize action areas, stations were ranked using a multicriteria approach based on: (i) percentage of users reporting no direct public transport connection, (ii) long average access times, and (iii) estimated time savings from bicycle use.

Once the survey data was collected, the responses underwent a cleaning process to remove duplicate entries and incomplete responses. The dataset was then analyzed using Microsoft Excel for initial cleaning and SPSS Statistics V29 for statistical analysis.

For the thematic coding of open-ended responses (if applicable), common themes were identified manually and grouped based on recurrent keywords related to barriers and preferences. Descriptive statistical techniques were applied to identify key patterns, such as travel time estimates, perceived barriers to metro use, and willingness to adopt multimodal commuting.

These methods ensured that the data was cleaned, coded, and analyzed in a way that allows for reliable replication in future studies.

This phase involved interpreting the results, extracting key insights, and translating them into actionable recommendations. The analysis highlighted critical connectivity and access barriers at metro stations—especially in peripheral areas such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde.

Further analysis examined users’ willingness to adopt combined bicycle-metro commuting. Students and younger demographics demonstrated higher acceptance, particularly where adequate infrastructure is provided. These findings were discussed in the context of international case studies, including systems in Medellín and Santiago, to derive locally adaptable strategies.

Finally, the study translated its findings into policy recommendations structured around three pillars: infrastructure development (e.g., bike lanes and secure parking at key stations), policy incentives (e.g., integrated fares and student discounts), and awareness campaigns to promote multimodal transport culture and increase perceived safety.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Survey Responses

The survey conducted in February 2023 among students at the Central University of Ecuador (UCE) revealed significant insights into the potential integration of bicycles with the Quito Metro system. A total of 522 valid responses were collected, with 60% of respondents expressing confidence in the metro’s ability to reduce traffic congestion. However, 40% expressed skepticism, citing concerns about lack of integration with other transport systems. A majority of the participants also reported that they would be willing to adopt the combined bicycle-metro system, particularly if secure bike parking and dedicated bike lanes were available at key metro stations.

The survey was conducted in February 2023 among students of the Central University of Ecuador (UCE), whose campus is located near several Metro de Quito stations. A total of 522 valid responses were collected. The questionnaire included over 15 closed-ended questions, primarily consisting of multiple-choice and Likert-scale items, aimed at understanding users’ perceptions of the Quito Metro, their travel behaviors, and willingness to adopt multimodal commuting.

The survey was distributed online via Google Forms and remained open for two weeks. All responses were exported to Microsoft Excel for preliminary data processing. The cleaning process involved removing duplicate or incomplete entries.

Closed-ended questions were analyzed descriptively to identify key trends such as perceived barriers to metro use, expected travel time savings, and willingness to combine bicycles with the metro system. Although no demographic data such as age or gender was collected, the sample reflects a population of young adult commuters familiar with urban mobility challenges.

The decision to focus exclusively on students from the Central University of Ecuador (UCE) was based on their representativeness as urban commuters with high exposure to both the Metro system and micromobility options. University students typically have flexible mobility patterns, rely more on non-private transport, and are more open to adopting sustainable travel behaviors. Moreover, their proximity to several key Metro stations and their daily commuting routines provide valuable insights into first- and last-mile challenges. While not representative of the entire population, this segment serves as a relevant proxy for potential modal shifts among younger, active urban residents in Quito.

Although students provide valuable insights into urban commuter behavior, future research should validate these findings with broader demographic groups to ensure wider applicability of the recommendations.

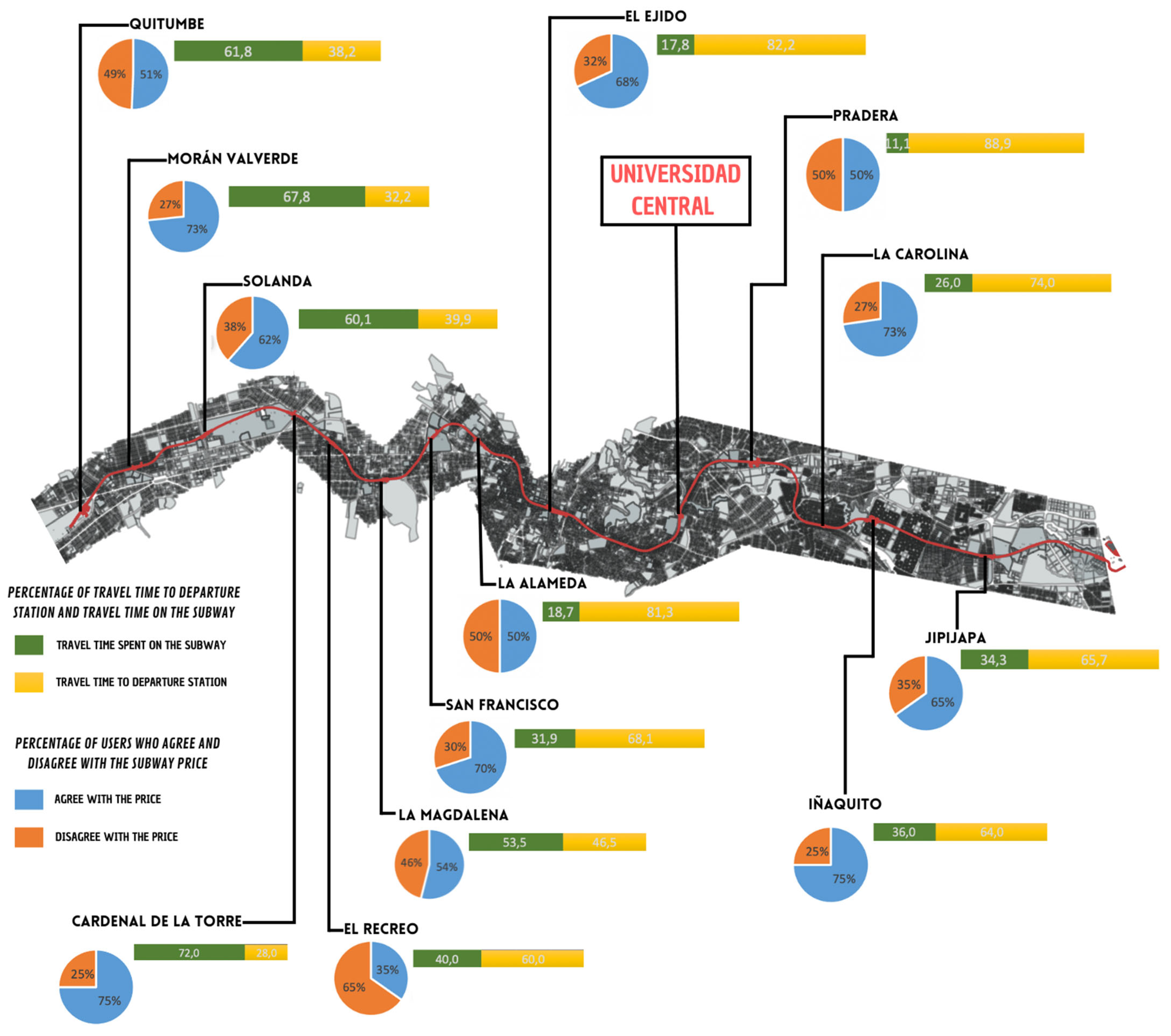

Although the Quito Metro consists of 15 stations, this study focuses on 13 stations identified as relevant access points by survey participants. The 14th location included in the analysis is the Central University station, which represents the target destination for all respondents. This structure reflects the directionality of the commuting analysis: from one of the 13 departure stations to the university.

The 15th station, El Labrador, was not selected by any respondents as a point of departure. This may be due to its geographic location, limited residential catchment area, or operational timeline at the time of the survey. Preliminary field observations suggest that El Labrador primarily serves institutional or administrative zones, with low residential density nearby. Therefore, its exclusion from the dataset was not by design but reflects actual user behavior and spatial dynamics.

For clarity, the updated

Figure 2 is an original schematic map developed by the authors to represent the stations covered in the study. It does not reproduce official metro system materials and has been designed to avoid copyright issues while reflecting the structure and findings of the analysis.

The number of stations shown in each figure varies depending on data completeness and minimum response thresholds. Only stations with at least 10 valid responses were included in the analysis to ensure representativeness and statistical reliability. The full list of reported stations includes: Cardenal de la Torre, El Ejido, El Recreo Metro, Iñaquito, Jipijapa, La Alameda, La Carolina, La Magdalena, La Pradera, Morán Valverde, Quitumbe, San Francisco, and Solanda (

Figure 2).

Although the Quito Metro system consists of 15 stations, this study focuses on 13 stations identified as relevant by survey participants. The Central University station, a key destination for all respondents, was included as the 14th station for analysis. The 15th station, El Labrador, was not selected by any participants, likely due to its limited accessibility and the low residential density surrounding it. The revised

Figure 2 clearly shows the 14 stations considered in this study and the connections with other public transport modes such as Ecovía, Trolebús, and bus routes.

To provide a clearer context of the Quito Metro system, a map is included below (

Figure 2) that shows the 15 stations and their connections with other transport modes such as Ecovía, Trolebús, and local bus lines. This map aims to enhance the understanding of the metro’s position within the broader urban transport network.

If

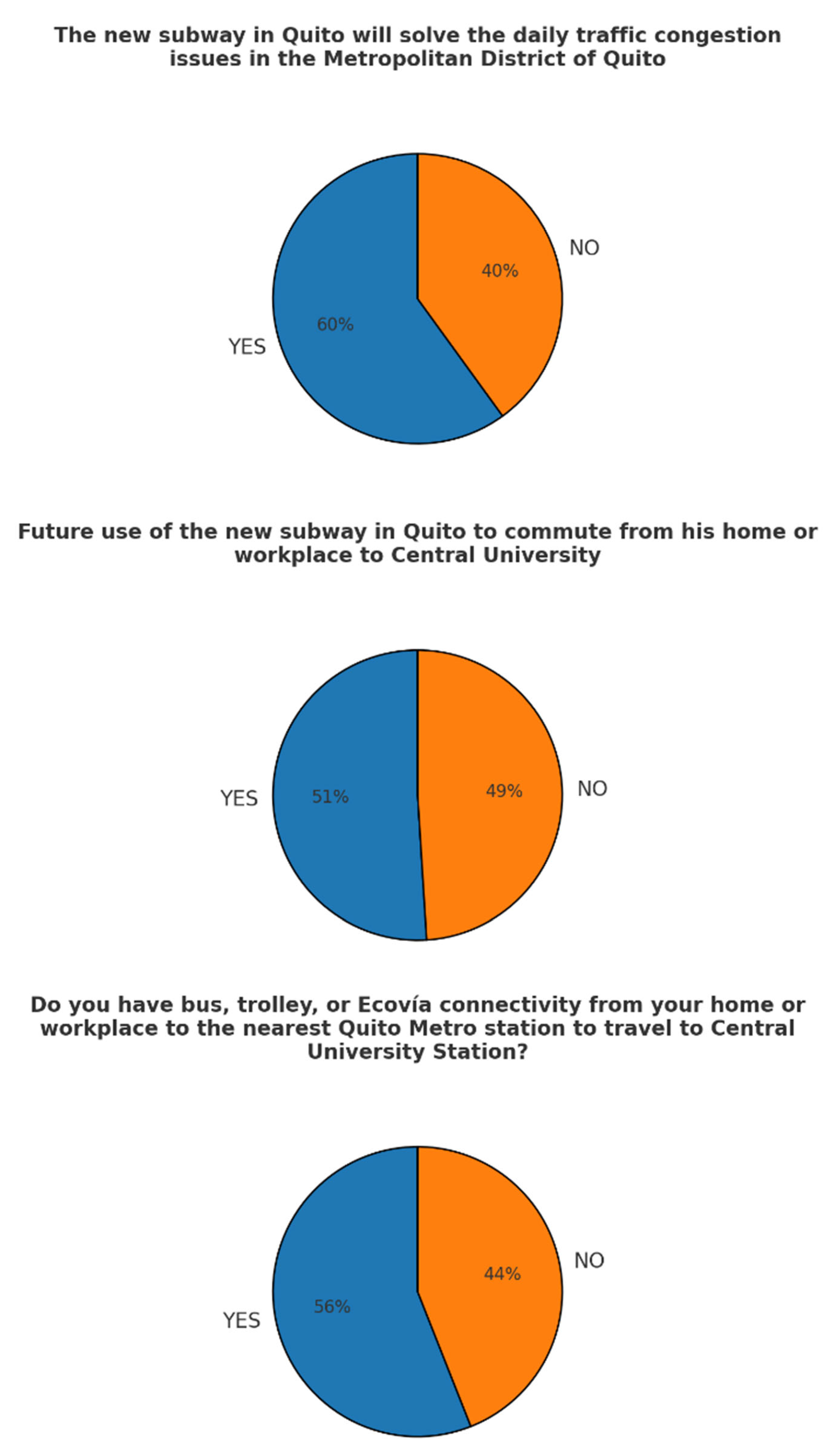

Figure 3 is analyzed, regarding the solution to traffic congestion in the Metropolitan District of Quito, 60% of respondents believe that the new metro system will solve the daily problems of traffic congestion in the Metropolitan District of Quito. But 40% express skepticism, which could be due to the perception of structural barriers, such as lack of integration with other transportation systems or widespread saturation of urban infrastructure.

Most have positive expectations regarding the impact of the metro on urban mobility. However, the skepticism of a minority highlights the need for complementary strategies to maximize its effectiveness, such as improvements in connectivity and information campaigns to increase confidence in the system.

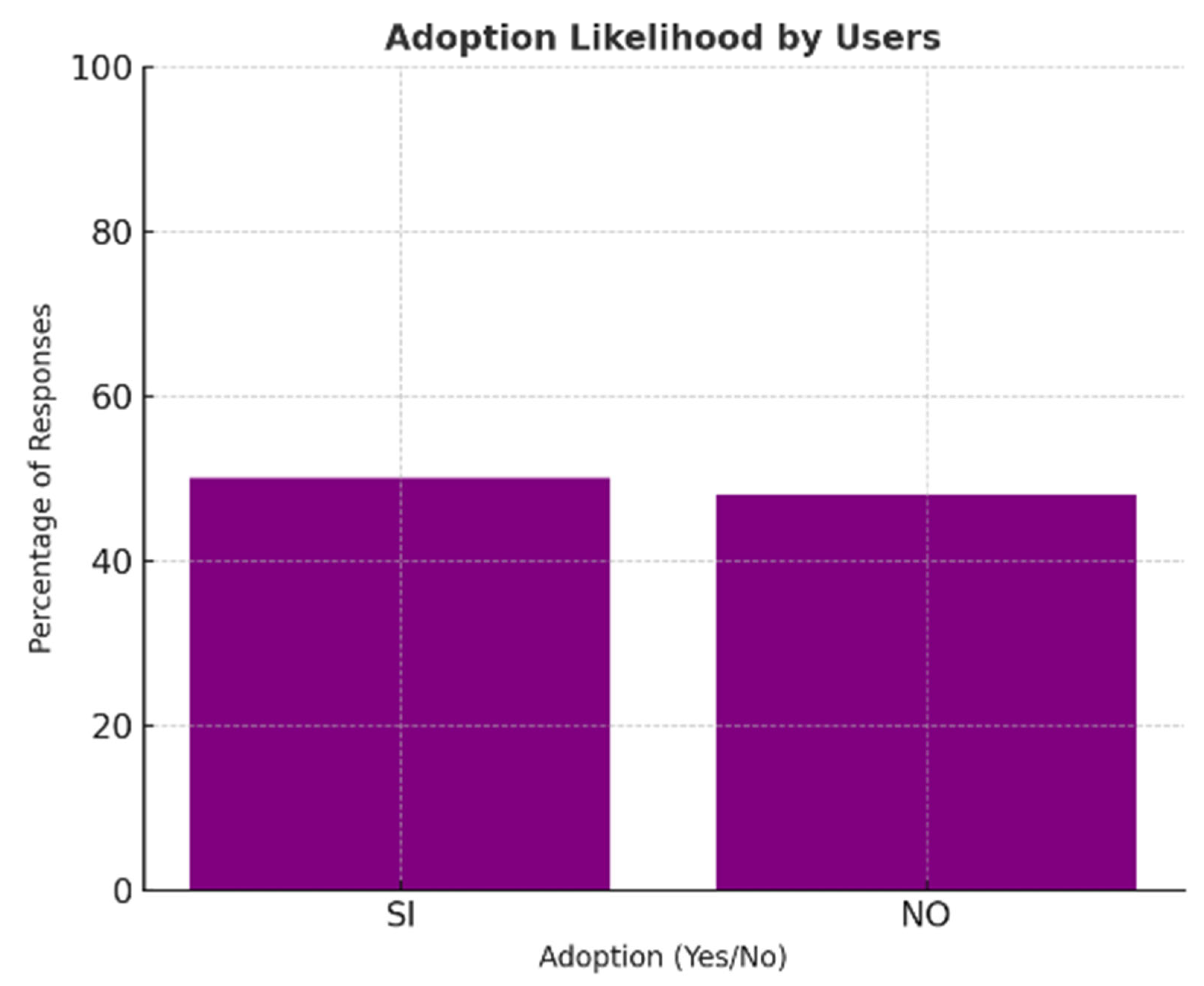

If asked about the future use of the metro to travel to the Central University, 51% of those surveyed plan to use the metro to travel from their homes or workplaces to the Central University, while the remaining 49% do not consider the metro as a viable option for this purpose.

The intention of use is almost divided. Factors such as proximity to stations, the cost of fares, and the perception of convenience and efficiency could influence the decision. This result suggests that the metro has the potential to capture a large proportion of users, but it requires addressing the current barriers that limit its adoption.

If connectivity with other transport systems is analysed, 56% of those surveyed indicate that they do not have a direct connection by bus, trolleybus or Ecovía to reach the nearest metro station, only 44% have access to a direct connection.

The lack of connectivity is a major challenge that could limit the use of the metro. This data underscores the need to strengthen integration between the metro and other public transport systems to maximise their accessibility and attract more users.

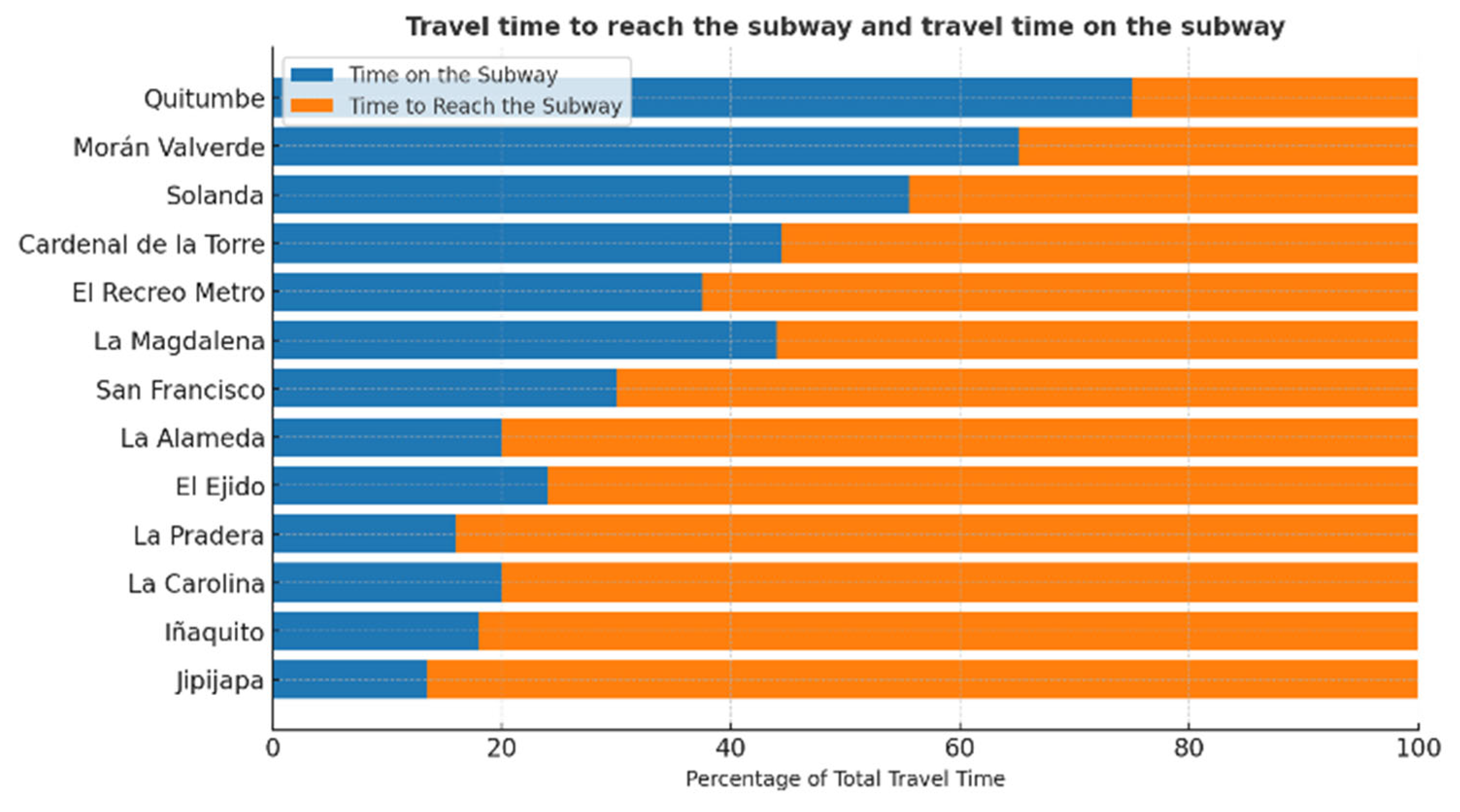

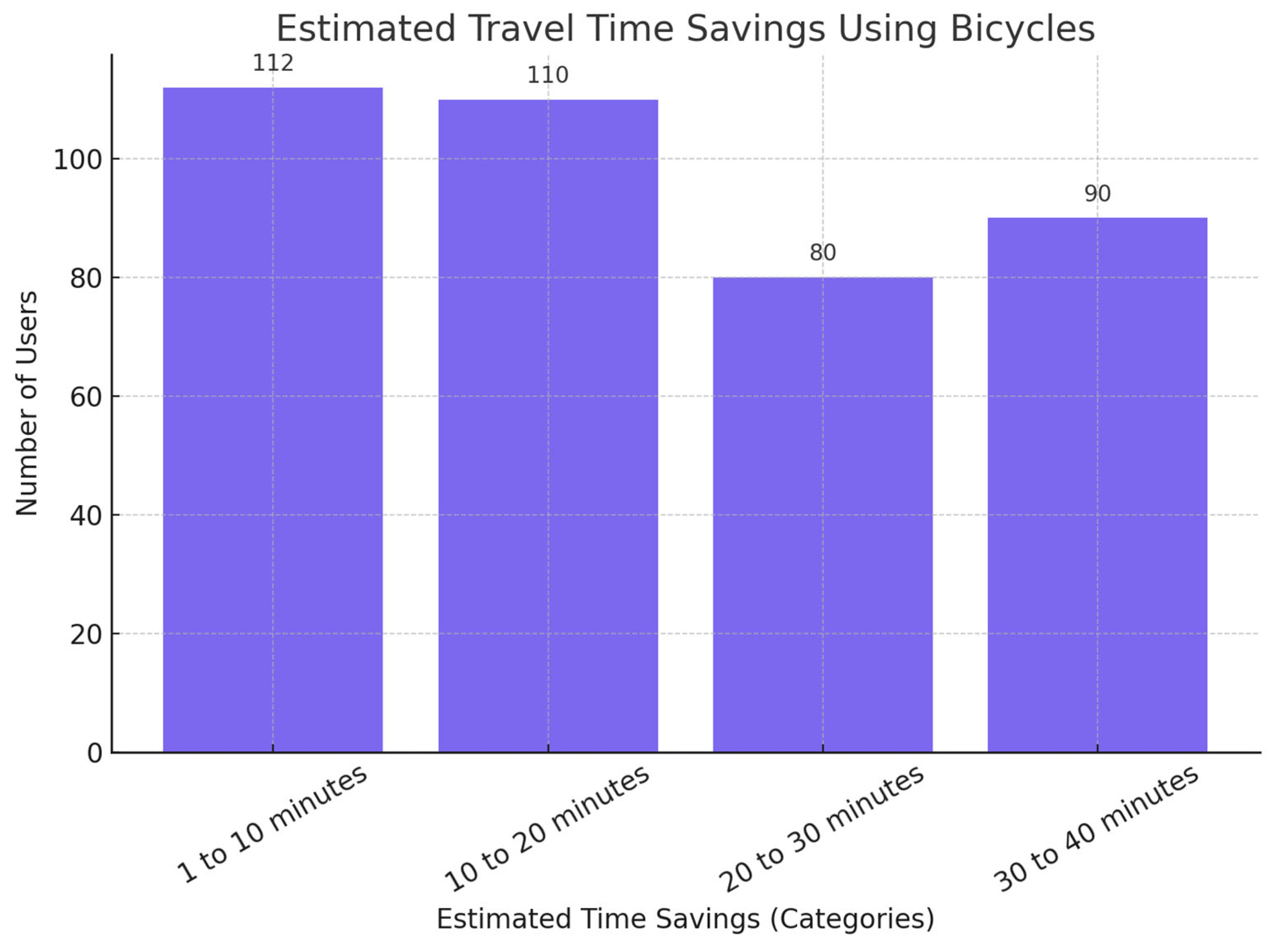

The analysis of the perceptions and intentions of use of the Quito Metro reveals a mixed panorama, but with great potential to transform the urban mobility of the city. On the one hand, the majority of respondents are confident that the subway will reduce traffic congestion, and a significant proportion anticipate significant time savings in their daily commutes (

Figure 4). These results position the metro as a promising solution to mobility challenges, especially for users who currently face long travel times and inefficient transport conditions. However, the system also faces significant barriers that must be addressed to maximize its impact.

This figure displays the reported access times to metro stations, as calculated from survey data. These access times were compared with simulated time savings, which suggest potential reductions of up to 30%.

The analysis of connectivity and accessibility highlighted significant barriers at key metro stations in Quito. For example, 64.3% of users reported lacking direct connections to public transportation systems at La Alameda, and 62.5% faced similar issues at Iñaquito. Additionally, peripheral stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde were identified as having notable challenges related to access. These findings suggest that integrating complementary transport solutions, such as bicycles, could address these deficiencies effectively.

4.2. Impact on Travel Time and Potential Benefits

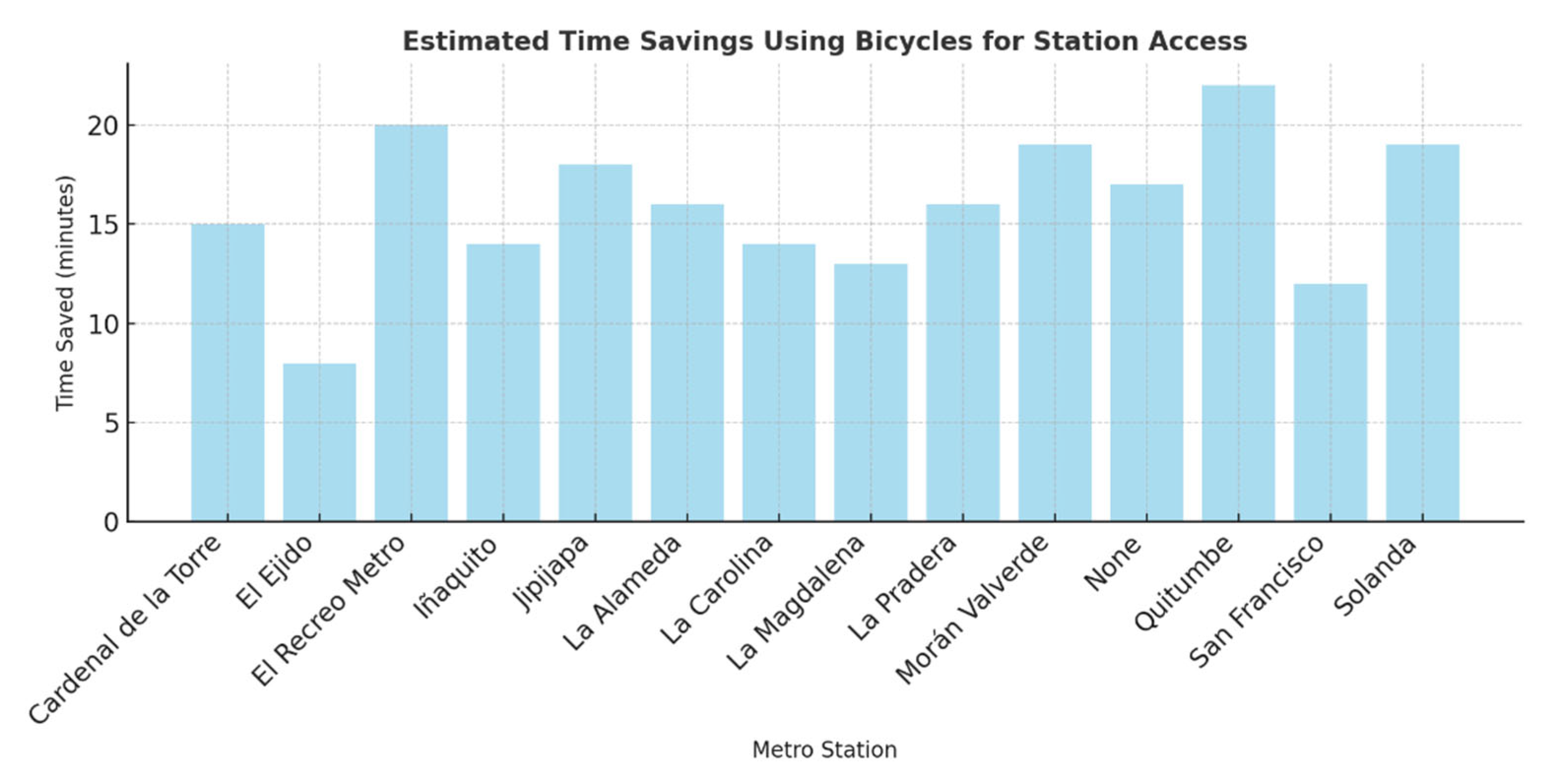

The study’s simulations show that integrating bicycles with the metro system could reduce access times by up to 30%, resulting in potential savings of 22.76 min for users of peripheral stations like Quitumbe and Morán Valverde. This is particularly significant for daily commuters facing long access times of 45–75 min. These findings align with previous studies on micromobility, which suggest that bicycle integration can significantly reduce travel times and improve accessibility to mass transit. Furthermore, stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, which are located farther from the city center, stand to benefit most from this integration, making it a key strategy for improving the overall efficiency of the metro system.

To estimate the potential time savings when integrating bicycles into the metro system, we used data on current average access times to metro stations, reported by respondents. A reduction of 30% in access time was applied to these average values, based on findings from previous micromobility studies. This reduction was calculated as a simple percentage of the reported access times, resulting in the following average savings: 22.76 min: Estimated average savings for users at peripheral stations, specifically Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, based on the 30% reduction.

Travel time analysis further emphasized inefficiencies, with average times to peripheral stations ranging from 45 to 75 min. Simulations conducted as part of this study demonstrated that integrating bicycles as a first- and last-mile feeder mode could reduce travel times by approximately 30%, resulting in potential savings of up to 22.76 min for users of key stations like Quitumbe. This saving time is particularly significant for daily commuters traveling long distances.

To estimate the potential time savings when integrating bicycles into the metro system, we used survey data on current average access times to metro stations, as reported by respondents. A 30% reduction in access times was applied to these values based on findings from previous micromobility studies This reduction was calculated as a simple percentage of the reported access times.

The estimated 22.76 min of time savings was calculated specifically for stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, which were identified as having the highest reported access times. This simulation reflects the best-case scenario in which bicycles are adopted as a first- and last-mile solution, providing direct access to metro stations and bypassing traffic congestion.

Travel time analysis confirmed that users of these stations face delays exceeding 45 min, while simulations projected savings of up to 22.76 min with bicycle integration.

The study also examined user adoption patterns. Younger demographics, particularly students, exhibited a higher willingness to adopt a combined bicycle-metro transport system. However, several barriers hinder adoption, including the lack of secure bicycle parking facilities and inadequate cycling infrastructure. Addressing these challenges is critical to unlocking the full potential of a bicycle-metro integration strategy.

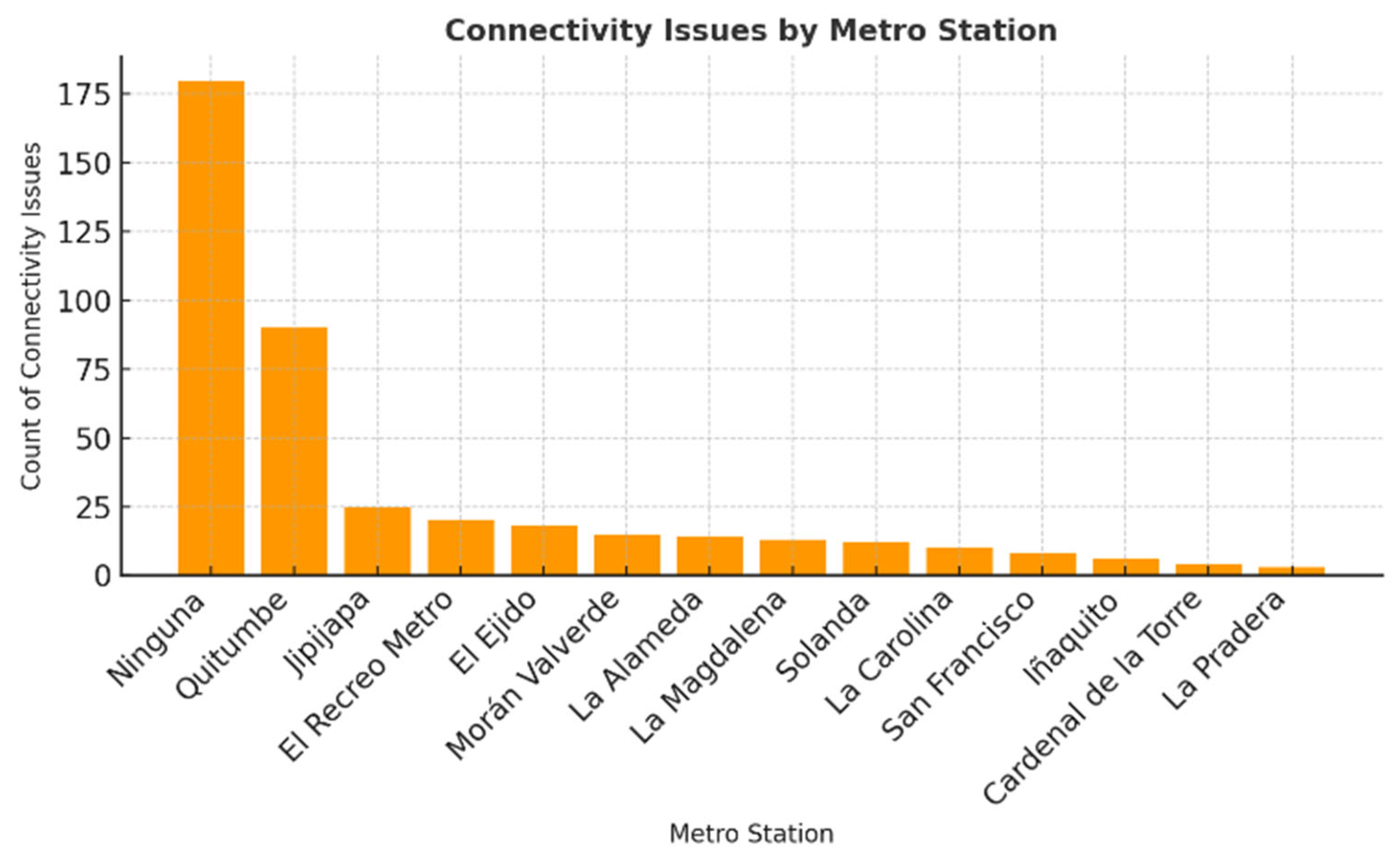

Figure 5 visualizes the users reporting connectivity barriers for major metro stations. It highlights how La Alameda and Iñaquito have the most significant issues, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

The “connectivity barriers” refer to the absence of direct connections between the selected metro stations and other modes of transport (bus, trolleybus, Ecovía). These barriers were identified based on survey responses, where users indicated whether they had direct access to the metro stations via these systems. Stations such as La Alameda and Iñaquito were identified as having the highest connectivity issues, with 64.3% and 62.5% of respondents, respectively, reporting a lack of direct connection.

Figure 5 presents the total number of users reporting a lack of direct bicycle connections at each station, based on responses to a multiple-choice survey question.

This bar chart (

Figure 6) presents the potential travel time savings (in minutes) for users of key metro stations. It shows that stations like Quitumbe and Morán Valverde would experience the greatest benefit from the integration of bicycles.

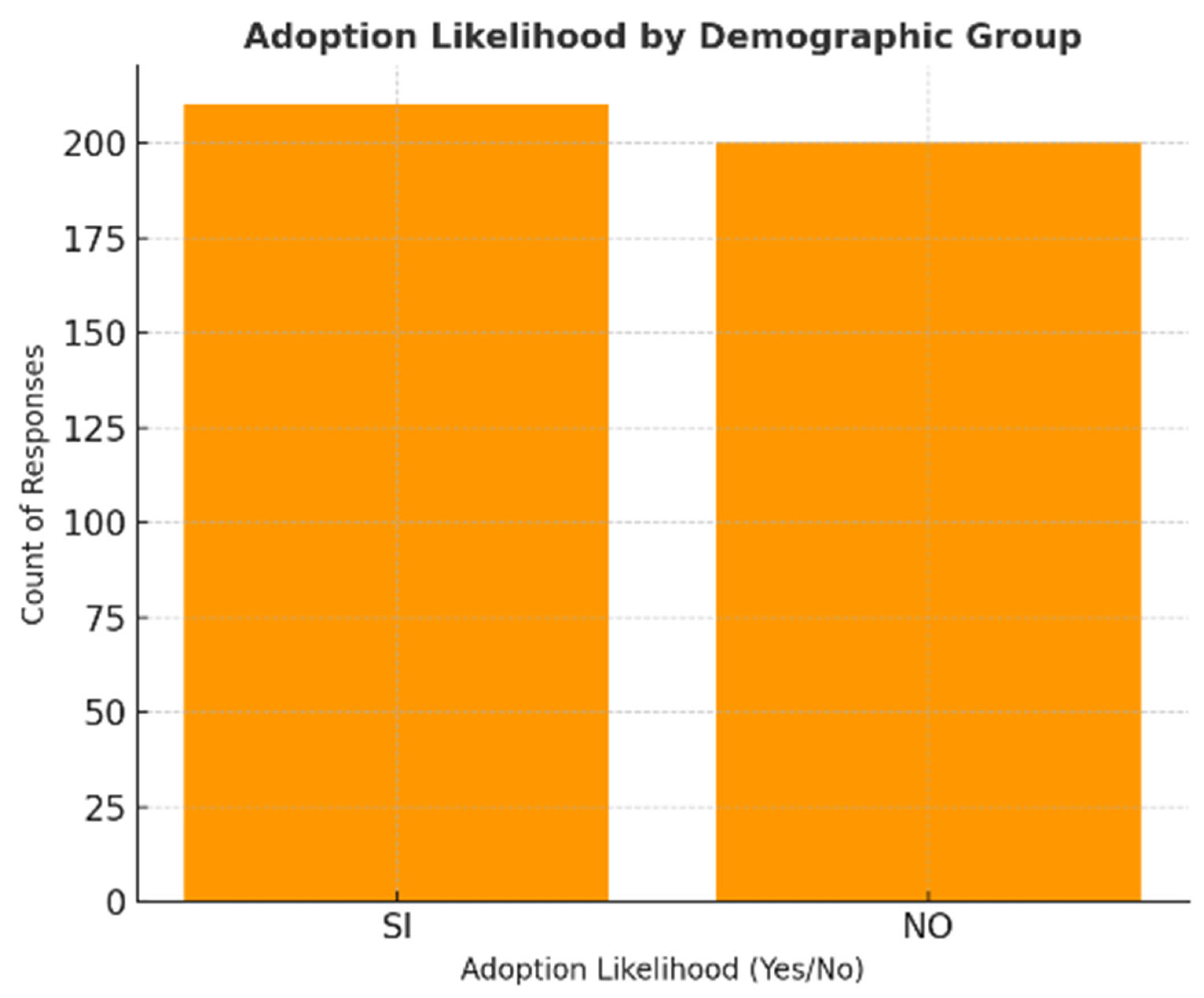

This graph (

Figure 7) depicts the likelihood of adopting a combined bicycle-metro system among various demographic groups (e.g., students, young professionals, and adults). Students are shown to have the highest likelihood of adoption, reinforcing the importance of targeting this group in promotional strategies.

The analysis highlights the critical impact that peripheral stations, such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, have on the adoption and effectiveness of the metro system in Quito. These stations have the greatest potential for improvement due to their strategic location in underserved areas. Solving access barriers at these stations could significantly increase metro use and reduce travel times, especially for users who currently face greater connectivity difficulties (

Figure 8).

This

Figure 8 presents connectivity barriers across stations, with data reflecting the percentage of respondents reporting a lack of direct connections to public transport systems (bus, trolleybus, Ecovía).

Figure 8 displays the same data normalized as percentages of total re-sponses per station to enable comparative analysis.

The integration of bicycles as a solution for the first and last legs of the journey offers tangible benefits for users of the transport system. This strategy could reduce reliance on congested roads and public transport hotspots, while promoting more sustainable mobility habits. However, there are challenges that need to be addressed, such as the lack of safe infrastructure for cyclists, including bike lanes and protected parking lots, and user concerns about the safety of routes in peripheral areas.

International experience in cities such as Medellín and Santiago provides valuable lessons for Quito. In these cities, the implementation of integrated fare systems, which cover both access to the metro and the use of bicycles, has encouraged multimodal transport. In addition, the development of feeder routes, such as dedicated bike lanes and bike-sharing systems connected to public transit stations, has improved accessibility and encouraged the adoption of these systems.

The analysis of the data reveals that the La Alameda and Iñaquito stations are the ones with the greatest connectivity problems, with 64.3% and 62.5% of users reporting a lack of direct connections, respectively. In addition, peripheral stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde also face significant barriers, which negatively impacts their adoption as key points of the metro system (

Figure 9).

Current travel times to access metro stations range, on average, between 45 and 75 min in peripheral areas, with the general average being 59.25 min. This reinforces the need to implement complementary modes such as bicycles to reduce these delays (

Figure 10).

The analysis shows that the use of bicycles could reduce access times by an average of 30%, representing an estimated average savings of 18.69 min. Stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde are priorities for the implementation of cycling infrastructure, with potential savings of 22.76 min and 18.8 min, respectively. Other stations such as El Recreo Metro and Solanda also present significant savings, more than 18 min.

Estimated travel time savings are presented for stations with high connectivity barriers, such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde. The simulations show a potential reduction of up to 22.76 min based on the 30% access time reduction

Analysis of the responses indicates that a significant majority of users, more than 50%, would be willing to use the combined bicycle and metro system. This pattern is particularly evident in younger groups and students, who show greater willingness to adopt this system, provided that there is adequate infrastructure, such as safe bike lanes and protected parking at stations (

Figure 11).

While

Figure 7 shows the absolute number of users selecting each option,

Figure 11 reflects the same distribution as a percentage of total answers, allowing a proportional comparison across categories.

A 30% reduction in access time was modeled based on literature benchmarks and applied uniformly to the average reported access times from the survey. This scenario reflects typical improvements reported in micromobility integration studies and is used here as a reference for potential time savings.

4.3. Challenges of Implementation and Policy Recommendations

Despite the promising benefits of integrating bicycles with the Quito Metro, several challenges remain. The lack of sufficient cycling infrastructure, such as protected bike lanes and secure bike parking, presents significant barriers. Moreover, institutional coordination is needed between various transport authorities to ensure the integration of bicycle lanes with metro stations. Addressing these challenges requires significant public investment and policy changes. Additionally, public perceptions about cycling safety and concerns about the status of bicycles as a mode of transport could hinder widespread adoption. To address these challenges, we recommend the implementation of integrated fare systems, public awareness campaigns, and targeted youth incentives to promote the adoption of a combined bicycle-metro system.

Figure 12 shows the estimated time savings when using bicycles as a means of access to Quito Metro stations. This finding reinforces the idea that the integration of the bicycle with the metro can improve urban mobility, especially in peripheral stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, where access times to the metro are considerably high. Analysis of this data suggests that the use of bicycles can significantly reduce commuting times, allowing more users to opt for the metro as their primary mode of transportation. In addition, stations with connectivity problems, such as La Alameda and Iñaquito, could benefit from cycling infrastructure that facilitates efficient and fast access to the mass transit system.

From a strategic point of view, these results highlight the importance of implementing sustainable mobility policies that encourage the use of bicycles as a key complement to public transport. The construction of safe bike lanes, the installation of bicycle parking in strategic stations and the adoption of integrated fares for bicycles and the metro are measures that can maximize the adoption of this model. In addition, the implementation of awareness campaigns can increase the perception of safety and convenience of this mobility alternative, encouraging its use and improving the efficiency of the transport system in Quito.

In addition, the results obtained underline the need to address existing barriers to the adoption of combined bicycle and metro use. Although the estimated savings times are significant, factors such as the perception of safety in the cycling infrastructure and the availability of adequate spaces for bicycle parking can influence the willingness of users to adopt this mode of transport. In particular, stations located in peripheral areas require a specific approach that guarantees connectivity with safe bike lanes and well-marked routes, preventing users from facing additional difficulties on their way to metro stations.

The implementation of the proposed recommendations faces several challenges, particularly regarding the institutional coordination needed between various transport authorities and urban planners. The development of adequate cycling infrastructure requires significant public investment, which may be difficult to secure in the context of limited budgets and competing infrastructure priorities. Additionally, cultural barriers related to the perception of bicycles as a lower-status transport mode and concerns about safety may hinder adoption. These issues require a comprehensive policy approach, including awareness campaigns, stakeholder engagement, and integrated fare systems to ensure successful implementation.

On the other hand, the experience of Latin American cities with successful intermodal transport models, such as the Medellín Metro or the TransMilenio de Bogotá, shows the importance of integrating fare systems that allow a more accessible and convenient use of bicycles in combination with the metro. Implementing incentives such as reduced fares for those who use both modes of transportation or the creation of bicycle rental programs could further enhance the effectiveness of this strategy. In this way, the integration of the metro and bicycle in Quito can not only optimize travel times and reduce traffic congestion, but also promote a sustainable mobility model that benefits the entire population.

While the proposed recommendations are grounded in the perceptions and preferences of urban commuters, their implementation faces several critical challenges. First, the integration of cycling and public transport systems requires coordination among multiple institutions—such as transit authorities, urban planners, and local governments—which often operate in silos. Second, infrastructure upgrades (e.g., building safe bike lanes and secure parking near metro stations) demand substantial public investment and political will, both of which can be inconsistent over time. Third, public perceptions and cultural norms—such as the association of bicycles with lower social status or concerns about personal safety—may hinder widespread adoption. These challenges underscore the importance of combining infrastructure and policy reforms with awareness campaigns and stakeholder engagement to ensure that proposed solutions are viable, equitable, and sustainable.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of integrating bicycle use as a solution to improve the connectivity and efficiency of the public transport system in Quito. Peripheral stations, such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, stand out as priority areas due to the significant access barriers and long travel times faced by their users. The adoption of bicycles as a first- and last-mile solution could reduce travel times by an average of 30%, achieving savings of more than 22 min at key stations. In addition, the results show that younger demographics, especially students, are more willing to combine bicycles and subways, as long as adequate and safe infrastructure is ensured.

This work provides evidence that can guide urban planners and policymakers in formulating sustainable transport strategies. The results highlight the need to prioritize investments in cycling infrastructure, implement integrated fare policies, and encourage the use of the bicycle-metro system, contributing to a more efficient, accessible, and environmentally friendly transport system.

However, the study has some limitations, including the representativeness of the data and the theoretical nature of the time-saving estimates. The results must be validated through pilot projects and longitudinal studies that analyze the real impact of the proposed measures on the adoption of the system and on the reduction in travel times. There is also a need to expand the analysis to other areas and transport systems in the city to ensure the applicability of these recommendations on a wider scale.

The recommendations obtained from the results obtained in the research are (

Table 2):

Based on the high access times at Quitumbe and Morán Valverde (

Figure 10), secure parking and direct bicycle corridors are prioritized.

The high intention to use the system among students (

Figure 11) supports the recommendation of youth-focused incentives.

Overall, this study provides a solid foundation for implementing micromobility strategies that not only improve the quality of public transport in Quito, but also contribute to broader sustainability and urban quality of life goals. Collaboration between local authorities, users, and other key actors will be critical to the success of these initiatives.

The integration of bicycles with the Quito Metro presents an opportunity to improve urban mobility, especially in peripheral areas with connectivity problems. With adequate infrastructure and inclusive policies, this strategy could increase metro adoption, reduce travel times, and encourage more sustainable transportation in the city.

Despite the positive impact that the Quito Metro can generate on urban mobility, the study’s findings suggest that its effectiveness will depend largely on integration with other modes of transport, particularly in peripheral areas. The lack of connectivity with other public transport systems remains a key barrier, especially at stations such as Quitumbe and Morán Valverde, where access times remain considerably high. In this sense, the implementation of efficient feeder routes that are well coordinated with the metro schedules is presented as a fundamental strategy to maximize its accessibility and attract a greater number of users.

In addition, the results highlight the need to strengthen cycling infrastructure as a viable solution to reduce access times to metro stations. The construction of safe bike lanes, the installation of adequate bicycle parking spaces, and the promotion of public bicycle programs could significantly encourage the use of this mode of transport in combination with the metro. The experience of other cities has shown that the adoption of integrated fares and the implementation of incentives, such as discounts for those who combine bicycle and metro, can increase the adoption of the system and reduce dependence on motorized transport.

Finally, it will be key to work on communication and citizen awareness strategies to promote modal integration and improve the perception of safety in the use of bicycles. Educational campaigns on the benefits of combined use of bicycles and the metro, together with initiatives to improve road safety, can contribute to a cultural change that favors a more sustainable mobility model. In this way, the optimization of Quito’s transport system will not only depend on the infrastructure of the metro itself, but also on the implementation of comprehensive strategies that guarantee its accessibility, efficiency, and acceptance by the population.

In addition to their practical implications, the findings contribute to the methodological discussion on how to measure access-time savings and behavioral shifts in micromobility adoption. By combining perception-based survey data with scenario simulations, this study offers a replicable framework to assess first- and last-mile connectivity improvements in emerging urban contexts. Furthermore, it highlights the need to adapt micromobility policies to localized commuting patterns, suggesting that age, trip purpose, and proximity to infrastructure are critical variables often underrepresented in regional transport planning. Future research could explore comparative applications of this framework in other Latin American cities, broadening the empirical base for inclusive and multimodal urban mobility strategies.

While the conclusions provide practical recommendations for policy and infrastructure development, they also contribute to the scientific discourse on micromobility integration by introducing a novel methodological approach to measuring access time reductions and analyzing user perceptions. This study offers a replicable framework for integrating bicycles with metro systems in emerging cities, which can be used in future research to explore similar issues in other urban contexts.