These Boots Are Made for Walking: A Qualitative Study on the Perceived Barriers to Pedestrian Mobility in Madrid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Project and Objectives

- Identify the main factors that encourage or deter pedestrians from using the street as a transportation infrastructure

- Analyze how different factors can influence walking choices and routes in the built environment

- Prioritize and organize the factors according to their importance and types of pedestrians

3. Literature Context for the Study

3.1. Accessibility

3.2. Safety/Security

3.3. Comfort

3.4. Attractiveness

3.5. Health

3.6. Resulting Factors According to the Different Content Blocks

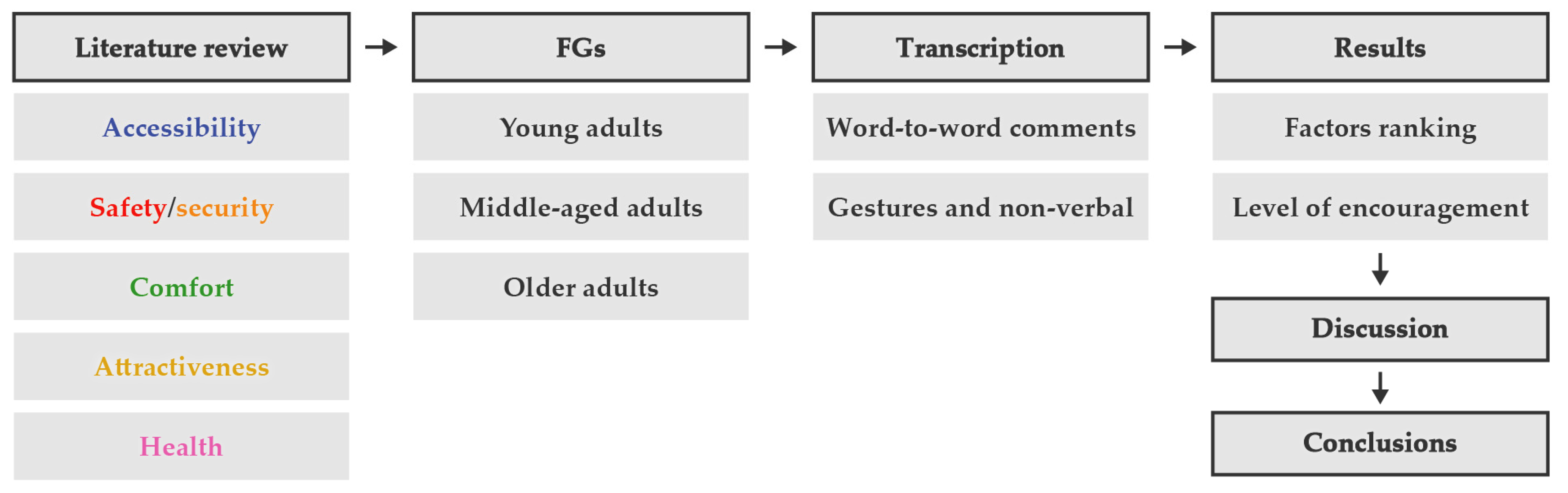

4. Methodology

- Young adults (18 to 34 years old), held in the Civil Engineering Faculty at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM). Made up of six people, three of them being women.

- Middle-aged adults (35 to 64 years old), held in the Civil Engineering Faculty at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM). Made up of seven people, four of them being women.

- Older adults—retired (over 65 years old), held in a Social Community Center from Madrid. Made up of seven people, five of them being women.

- Two moderators to grant full participation of all the attendees. They were in charge of introducing the different blocks of discussion, with no fixed questions to keep the dialogue as natural as possible. They allowed free debate on the most relevant factors according to the participants. No distinction was made to the aim of the pedestrian trip, as every destination could provide valuable inputs on the topic, showing different needs for different purposes.

- One reporter to note down all the reactions that did not reflect on audio.

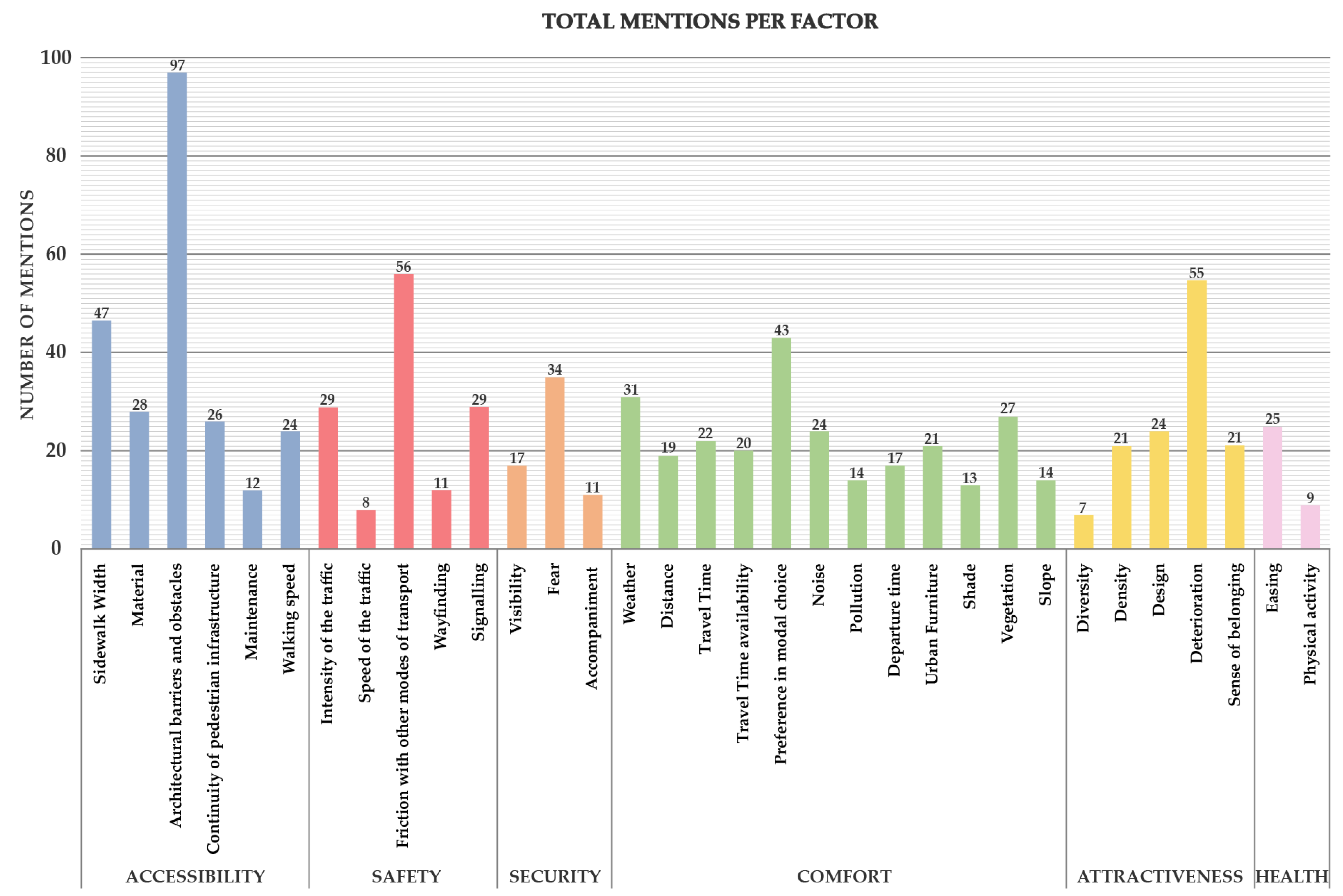

- Factors ranking: Ranking on the relevance of the different factors for pedestrians, measured by the number of mentions each of them received.

- Level of encouragement: Identification of the factors that hinder and foster walkability.

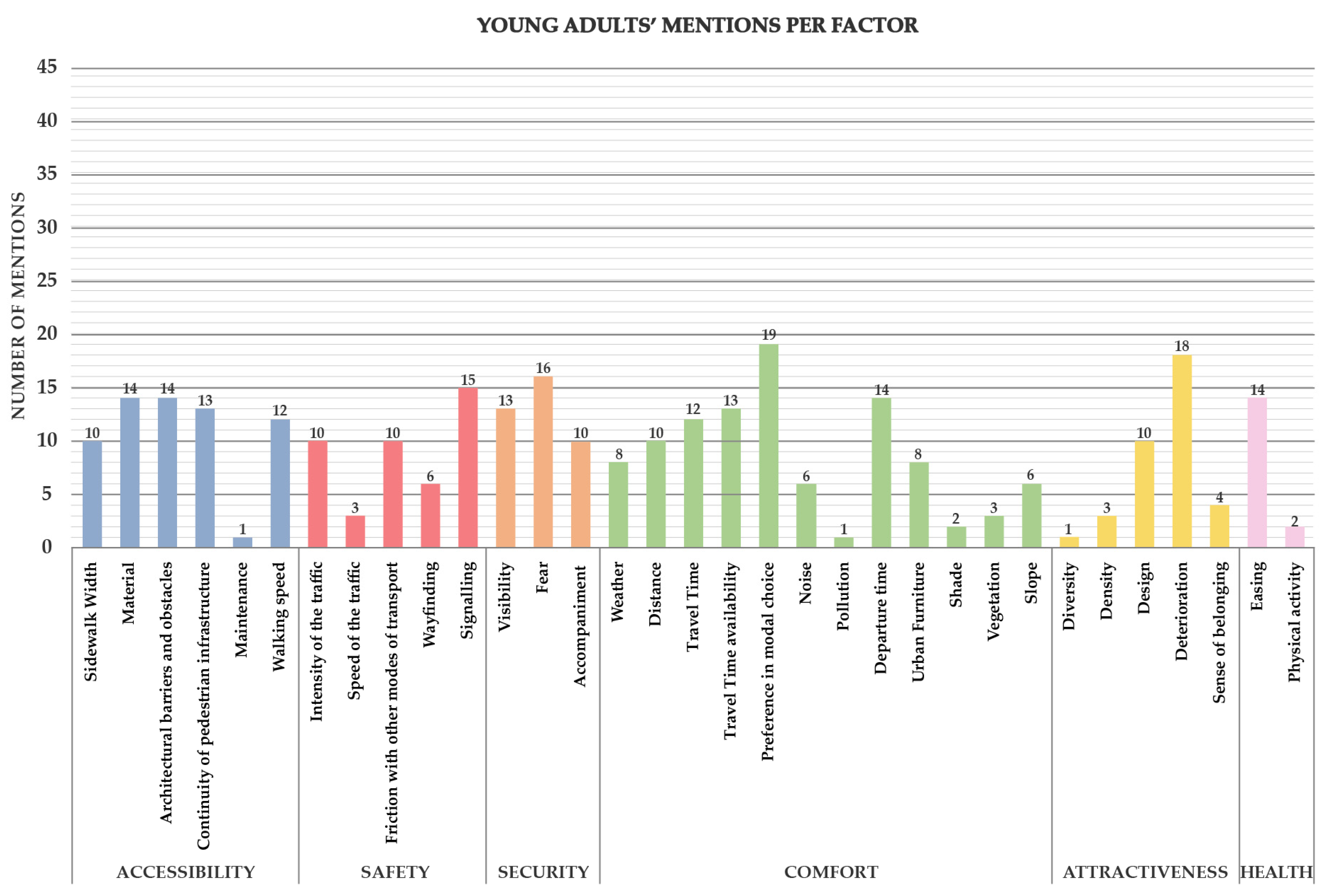

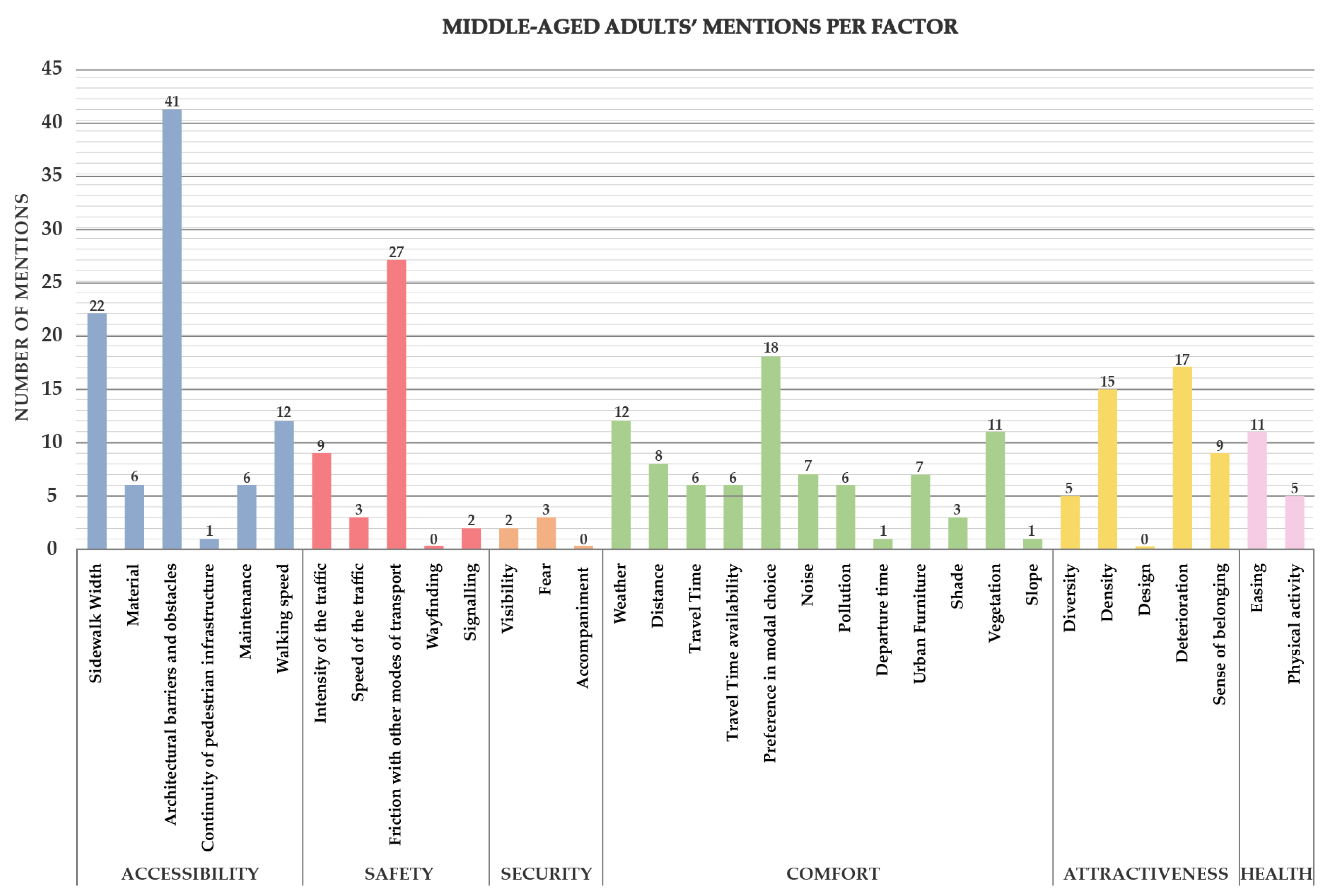

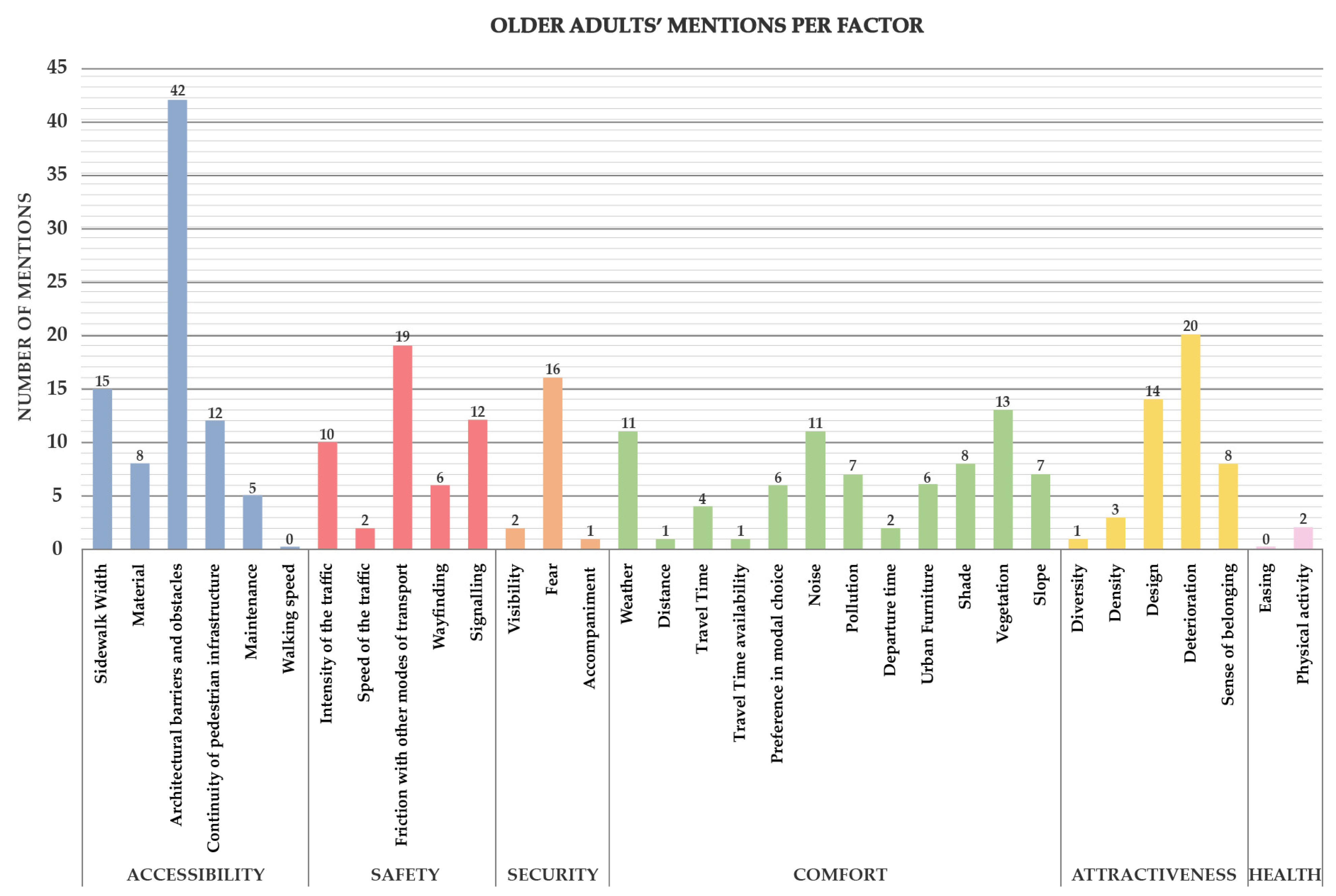

5. Results

5.1. Factors Ranking

5.2. Level of Encouragement and Discouragement

6. Discussion

6.1. Accessibility

“Next to the San Francisco bus stop […], there are four detached tiles that used to be of heavy stone and none could lift or move them […] Now, people run to catch the bus and then…bump! (referring to people falling).”.(76-year-old female)

“Terraces mean business for the local government, but they are annoying for pedestrians since they consume a lot of space”.(50-year-old male)

6.2. Safety

“We do not realize that people with disabilities or carrying a shopping cart do not move as easily as other people: they (motorbikes parked on pavements) are an obstacle, no matter how much space there is on the sidewalk”(44-year-old male)

“I cross the street using this traffic light every day and I can walk at a normal speed, but the traffic light does not last AT ALL.”.(74-year-old female)

6.3. Security

“Indeed, gender matters. After a certain hour at night, I never walk and I use a door-to-door transport. I always do it”(25-year-old female)

6.4. Comfort

“In the morning, on my way to work, I take the shortest route, and when I come back home, I prefer a wider street, which looks livelier and buildings look nicer”(25-year-old female)

“Weather conditions affect me the most: if the weather (referring to high temperatures or heavy rain) is bad, I use public transport; but if the weather is fine, I walk”.(44-year-old female)

“In the summer, I change my daily route depending on the shade […] if there is no shadow, I walk around the block to avoid going down some streets”(25-year-old female)

6.5. Attractiveness

“We place the value on having benches, fountains…, but their design does not match the needs, they are useless”(44-year-old male)

“If I am going to take a walk, I do it. If I go shopping, do errands, etc., I always do them in the neighbourhood while avoiding the main streets for their excessive noise. […] I do not like walking in the city centre of Madrid”(44-year-old male)

6.6. Health

“When I look at my mobile phone and it says that you have accomplished your daily objective, I am happy. It is a positive reinforcement”.(25-year-old female)

7. Limitations and Future Recommendations

- Reduced sample groups: the fact that each FG presented a reduced number of attendants eased the discussion process. Although the sample was not too big, different target groups were present, and they had plenty of time to express their comments and thoughts on the questions. Had it been other way, people would only have shared limited insights, which would have drawn biased conclusions only based on the predominant speakers.

- While allowing free debate in FGs, it is common to miss some gestures or non-verbal comments to express their perception of the suggested topic. Thus, the reporter played a crucial role in this regard and actively transcribed these messages and ideas to be included in the word-to-word transcription.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valenzuela-Montes, L.M.; Talavera-García, R. Entornos de movilidad peatonal: Una revisión de enfoques, factores y condicionantes. Eure 2015, 41, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.B. Great Streets. Access Mag. 1993, 1, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.R.; Morris, E.A.; Taylor, B.D. Planning for Cars in Cities: Planners, Engineers, and Freeways in the 20th Century. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Khomenko, S.; Cirach, M.; Pereira-Barboza, E.; Mueller, N.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Hoek, G.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Premature mortality due to air pollution in European cities: A health impact assessment. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e121–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency. Air Quality in Europe—2019 Report. October 2019. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Cambra, P. Pedestrian Accessibility and Attractiveness Indicators for Walkability Assessment; Dissertação para a Obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Urbanismo e Ordenamento do Território, Técnico Lisboa, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012; Available online: https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/395144992898/Dissertacao.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- González-Gross, M.; Meléndez, A. Sedentarism, active lifestyle and sport: Impact on health and obesity prevention. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28 (Suppl. S5), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallal, P.C.; Andersen, L.B.; Bull, F.C.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U.; Alkandari, J.R.; Bauman, A.E.; Blair, S.N.; Brownson, R.C.; et al. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Parkhurst, G.; Morgan, P.L. Psychological Wellbeing Benefits of Simulated Exposure to Five Urban Settings: An Experimental Study From the Pedestrian’s Perspective. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M. Children’s school commuting in the Netherlands: Does it matter how urban form is incorporated in mode choice models? Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2017, 11, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. Leisure-time physical activity, objective urban neighborhood built environment, and overweight and obesity of Chinese school-age children. J. Transp. Health 2018, 10, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.C.; King, D.A.; Lemar, S. Accessibility in Practice: 20-Minute City as a Sustainability Planning Goal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Ding, N.; Li, J.; Jin, X.F.; Xiao, H.; He, Z.M.; Su, S.L. The 15-min walkable neighborhoods: Measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogrusoy, I.T.; Dalgakiran, A. An alternative approach in sustainable planning: Slow urbanism. Archnet-IJAR 2011, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezoued, A.M.; Letesson, Q.; Kaufmann, V. Making the slow metropolis by designing walkability: A methodology for the evaluation of public space design and prioritizing pedestrian mobility. Urban Res. Pr. 2021, 15, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, A.; Dill, J.; Luhr, G.; Neal, M. Unpacking Walkability: Testing the Influence of Urban Design Features on Perceptions of Walking Environment Attractiveness. J. Urban Des. 2012, 17, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, S.; Nigro, M.; Petrelli, M. Walkability Indicators for Pedestrian-Friendly Design. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2014, 2464, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera-Garcia, R.; Soria-Lara, J.A. Q-PLOS, developing an alternative walking index. A method based on urban design quality. Cities 2015, 45, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonzo, M.A. To Walk or Not to Walk? The Hierarchy of Walking Needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozueta, J.; Daudén, F.J.L. Porto Schettino, and Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas. In La Ciudad Paseable: Recomendaciones para la Consideración de los Peatones en el Planeamiento, el Diseño Urbano y la Arquitectura; Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, E.; Martín, B.; De Isidro, Á.; Cuevas-Wizner, R. Street walking quality of the ‘Centro’ district, Madrid. J. Maps 2020, 16, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikiki, F.; Oikonomou, A.; Katartzi, E. Sustainable Mobility Issues of Physically Active University Students: The Case of Serres, Greece. Futur. Transp. 2021, 1, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, P.K.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Khattak, A.J. Space Syntax and Walking in a New Urbanist and Suburban Neighbourhoods. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.; Kochtitzky, C.S. Creating a Healthy Environment: The Impact of the Built Environment on Public Health. 2001. Available online: http://www.sprawlwatch.org/health.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Greenwald, M.J.; Boarnet, M.G. Built Environment as Determinant of Walking Behavior: Analyzing Nonwork Pedestrian Travel in Portland, Oregon. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2001, 1780, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britain, D. Inclusive Mobility: A Guide to Best Practice on Access to Pedestrian and Transport Infrastructure; Social Research in Transport (SORT) Clearinghouse: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gallez, C.; Motte-Baumvol, B. Inclusive Mobility or Inclusive Accessibility? A European Perspective. Cuad. Eur. Deusto 2017, 56, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; le Clercq, F.; Kapoen, L. Sustainable accessibility: A conceptual framework to integrate transport and land use plan-making. Two test-applications in the Netherlands and a reflection on the way forward. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Tiboni, M.; Vetturi, D.; Zazzi, M.; Caselli, B. Measuring Pedestrian Accessibility to Public Transport in Urban Areas: A GIS-based Discretisation Approach. Eur. Transp. Trasp. Eur. 2020, 76. Available online: http://www.istiee.unict.it/sites/default/files/files/1_2_ET_14.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Sanz Alduán, A. Calmar el Tráfico: Pasos para una Nueva Cultura de la Movilidad Urbana; Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://cpage.mpr.gob.es/producto/calmar-el-trafico-2/ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Kim, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.S. Meso- or micro-scale? Environmental factors influencing pedestrian satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 30, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikora, T.J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.W.; Bull, F.C.; Jamrozik, K.; Donovan, R.J. Neighborhood Environmental Factors Correlated with Walking Near Home. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Meeks, J.W.; Taylor, R.B. The physical environment of street blocks and resident perceptions of crime and disorder: Implications for theory and measurement. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zárate, M.R.; Estivill, J.; Eizagirre, N. La configuración y las consecuencias del miedo en el espacio público desde la perspectiva de género. REIS Rev. Española Investig. Sociológicas 2019, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, S.O. El lado nocturno de la vida cotidiana: Un análisis feminista de la planificación urbana nocturna. Ágora 2017, 4, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Qualitative Evaluation of Comfort Needs in Urban Walkways in Major Activity Centers. Transp. Q. 2003, 57, 39–59. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/view/682669 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Clark, A.; Scott, D.M.; Yiannakoulias, N. Examining the relationship between active travel, weather, and the built environment: A multilevel approach using a GPS-enhanced dataset. Transportation 2014, 41, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Tight, M.; Hodgson, F.; Page, M. A comparison of three methods for assessing the walkability of the pedestrian environment. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Kockelman, K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 1997, 2, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badland, H.; Schofield, G. Transport, urban design, and physical activity: An evidence-based update. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2005, 10, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Mundó, J.; Leonardi, M.; Chatterji, S.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Koskinen, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Haro, J.M.; Olaya, B. Loneliness and depression among older European adults: The role of perceived neighborhood built environment. Health Place 2020, 62, 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Dean, J.; Minaker, L. Urban design and adolescent mental health: A qualitative examination of adolescent emotional responses to pedestrian- and transit-oriented design and cognitive architecture concepts. Health Place 2022, 76, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados, S.H.B.; Cuéllar, Á.M.U. Influencia del deporte y la actividad física en el estado de salud físico y mental: Una revisión bibliográfica. In Katharsis; Revista de Ciencias Sociales: Envigado, Colombia, 2018; Volume 25, pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pineo, H. Towards healthy urbanism: Inclusive, equitable and sustainable (THRIVES)—An urban design and planning framework from theory to praxis. Cities Health 2020, 6, 974–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, E.R.; Kinsella, E.A.; Polzer, J. ‘Everything is down to the minute’: Clock time, crip time and the relational work of self-managing attendant services. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higueras, E.; Román, E.; Fariña, J. Guidelines for Healthier Public Spaces for the Elderly Population: Recommendations in the Spanish Context. In Handbook of Quality of Life and Sustainability; Martinez, J., Mikkelsen, C.A., Phillips, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J. ‘Stepping in Time’: Walking, Time, and Space in the City. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2009, 41, 1943–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, E.; Daniels, S.; Thierie, M.; Brijs, T. Safety effects of reducing the speed limit from 90 km/h to 70 km/h. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 62, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, S.; Ruiz, T.; Mars, L. A qualitative study on the role of the built environment for short walking trips. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 33, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A.; Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B. Environmental Factors Associated With Active Living in Retirement Village Residents: Findings From an Exploratory Qualitative Enquiry. Res. Aging 2013, 35, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Ju, Y.; Zhao, X. Risk factors related balance disorder for patients with dizziness/vertigo. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Brownson, R.C.; Cragg, E.S.; Dunn, A.L. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity: A study examining walking to work. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, S.L.; Clifton, K.J. Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel. Transportation 2001, 28, 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamíquiz Daudén, F.J. Implicaciones de la Accesibilidad Configuracional en la Movilidad Peatonal. El caso de Madrid = The Implications of Configurational Accessibility in Pedestrian Mobility. The Case of Madrid. Ph.D. Thesis, Escuela Técnica Superior de rquitectura de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2011. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/15031/ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Mueller, N.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Basagaña, X.; Cirach, M.; Cole-Hunter, T.; Dadvand, P.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Foraster, M.; Gascon, M.; Martínez, D.; et al. Urban and Transport Planning Related Exposures and Mortality: A Health Impact Assessment for Cities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Brauer, M.; Cohen, A.J.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Burnett, R.T.; Stanaway, J.D.; Causey, K.; Larson, S.; Godwin, W.; et al. The effect of air pollution on deaths, disease burden, and life expectancy across China and its provinces, 1990–2017: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e386–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A.; Dora, C. How the low carbon economy can improve health. BMJ 2012, 344, e1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S. Why cities need to take road space from cars—And how this could be done. J. Urban Des. 2020, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ACCESSIBILITY | Pavement Width | Total width for pedestrian infrastructure |

| Material | The material used on the pavement, as well as comments on the materials: paving, tile, or conglomerate | |

| Architectural barriers and obstacles | Element, fixed or semi-fixed, permanent or semi-permanent, which reduces the effective pavement width | |

| Continuity of the pedestrian infrastructure | Problems to continue the pedestrian route due to the absence of infrastructure or the inadequate resolution of intersections | |

| Maintenance | Preserve the quality of the infrastructure compared to the original | |

| Walking Speed | Pedestrian speed during the journey, being limited or reduced by infrastructure and/or the presence of crowds | |

| SAFETY | Traffic intensity | Number of vehicles running on a certain section of a street |

| Traffic speed | Speed of vehicles running on a certain section of street | |

| Friction with other Modes of Transport | Conflicts between pedestrians and other modes of transport (collective or individual), due to the invasion of the pavement | |

| Wayfinding | Intuitive understanding of the urban environment | |

| Signalling | Any indication, both vertical and horizontal, related to road safety in public spaces | |

| SECURITY | Visibility | Ease of pedestrians to see and be seen in a certain public space |

| Fear | Individual perception of the likelihood of accidents, both because of the infrastructure (falling) and by other individuals (physical assault) | |

| Accompaniment | The social act or the creation of social relationships while walking | |

| COMFORT | Weather | Set of atmospheric conditions |

| Distance | The total length of the pedestrian journey | |

| Travel Time | The time needed to complete the pedestrian journey | |

| Travel Time Availability | Having enough time or not requiring being at a certain time and place | |

| Preference in Modal Choice | Individual preference to walk versus other modes of transportation | |

| Noise | Atmospheric quality loss related to increased decibels | |

| Contamination | Atmospheric quality loss related to increased particulates and toxic substances in the air | |

| Departure Time | Variations in the itinerary caused by the start time of the journey | |

| Urban Furniture | Set of objects and pieces of equipment installed in the public space (benches, fountains, etc.) | |

| Shade | Public space without the incidence of the sun’s rays due to the presence of vegetation, buildings, or other elements | |

| Vegetation | Set of plants distributed in the urban space | |

| Slope | The inclination of infrastructure or public space by topography | |

| ATTRACTIVENESS | Diversity | Variety of land uses and commercial activities |

| Density | The concentration of commercial activities | |

| Design | Image and representativeness of space | |

| Deterioration | Variation of original design due to vandalism or dirtiness | |

| Sense of Belonging | The FG participant considers that it is part of the space, enjoying spaces and activities in the environment | |

| HEALTH | Easing | Spend time walking to improve individuals’ mental wellbeing |

| Physical Activity | The performance of physical exercise motivates the FG participant to walk in urban spaces |

| Kitzinger [50] and Krueger & Casey [49] Recommendations | Adaptations to the Present Case Study |

|---|---|

| It is advisable to create groups of 6 to 10 people that can represent different target groups. | Groups between 6 and 7 people were created. |

| The figures of the moderator and reporter are advised to guide and live-transcribe the sessions accordingly. | In each group, two moderators and one reporter guided the session to maintain a neutral position as far as possible. |

| The first step would be to raise the topic question and lead the participants to discuss freely the issues they consider more important. Moderators may arise some points that are not being considered or intervene if the discussion is going in a different direction than the set one. | The moderators only intervene to raise unexplored topics, and also presented examples to facilitate the debate. |

| Sessions need to be recorded to transcribe word by word the conclusions of the FG. | Full transcriptions were provided thanks to an audio recording. Once transcribed, live transcriptions of gestures and non-verbal communication were added. |

| The total length of the session ought to be 1 h and be dynamic. | Every session was 1 h long and was guided by the moderators, to keep the conversation active throughout the session. |

| Asp | Factor | % Imp | No. Mentions | % Imp per Age Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 35–64 | ≥65 | ||||

| AC | Architectural barriers and obstacles | 11.3% | 97 | 4.7% | 14.5% | 15.3% |

| SA | Friction with other Modes of Transport | 6.5% | 56 | 3.3% | 9.6% | 6.9% |

| AT | Deterioration | 6.4% | 55 | 6.0% | 6.0% | 7.3% |

| AC | Pavement width | 5.5% | 47 | 3.3% | 7.8% | 5.5% |

| CO | Preference in Modal Choice | 5.0% | 43 | 6.3% | 6.4% | 2.2% |

| SE | Fear | 4.1% | 35 | 5.3% | 1.1% | 5.8% |

| CO | Weather | 3.6% | 31 | 2.7% | 4.3% | 4.0% |

| SA | Traffic intensity | 3.4% | 29 | 3.3% | 3.2% | 3.6% |

| SA | Signaling | 3.4% | 29 | 5.0% | 0.7% | 4.4% |

| AC | Material | 3.3% | 28 | 4.7% | 2.1% | 2.9% |

| CO | Vegetation | 3.2% | 27 | 1.0% | 3.9% | 4.7% |

| AC | Continuity of pedestrian infrastructure | 3.0% | 26 | 4.3% | 0.4% | 4.4% |

| HE | Easing | 2.9% | 25 | 4.7% | 3.9% | 0.0% |

| AC | Walking Speed | 2.8% | 24 | 4.0% | 4.3% | 0.0% |

| CO | Noise | 2.8% | 24 | 2.0% | 2.5% | 4.0% |

| AT | Design | 2.8% | 24 | 3.3% | 0.0% | 5.1% |

| CO | Travel Time | 2.6% | 22 | 4.0% | 2.1% | 1.5% |

| CO | Urban Furniture | 2.5% | 21 | 2.7% | 2.5% | 2.2% |

| AT | Sense of Belonging | 2.5% | 21 | 1.0% | 5.3% | 1.1% |

| AT | Density | 2.5% | 21 | 1.3% | 3.2% | 2.9% |

| CO | Travel Time Availability | 2.3% | 20 | 4.3% | 2.1% | 0.4% |

| CO | Distance | 2.2% | 19 | 3.3% | 2.8% | 0.4% |

| SE | Visibility | 2.0% | 17 | 4.3% | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| CO | Departure Time | 1.9% | 17 | 4.7% | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| CO | Contamination | 1.6% | 14 | 0.3% | 2.1% | 2.5% |

| CO | Slope | 1.6% | 14 | 2.0% | 0.4% | 2.5% |

| CO | Shade | 1.5% | 13 | 0.7% | 1.1% | 2.9% |

| AC | Maintenance | 1.4% | 12 | 0.3% | 2.1% | 1.8% |

| SA | Wayfinding | 1.4% | 12 | 2.0% | 0.0% | 2.2% |

| SE | Accompaniment | 1.3% | 11 | 3.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% |

| HE | Physical Activity | 1.1% | 9 | 0.7% | 1.8% | 0.7% |

| SA | Traffic speed | 0.9% | 8 | 1.0% | 1.1% | 0.7% |

| AT | Diversity | 0.8% | 7 | 0.3% | 1.8% | 0.4% |

| Asp | Factor | % Average | % Positive Comments from Women | % Positive Comments from Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 35–64 | ≥65 | 18–34 | 35–64 | ≥65 | |||

| CO | Shade | 44.4% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 75.0% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 25.0% |

| CO | Departure Time | 35.7% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Vegetation | 30.2% | 66.7% | 27.3% | 53.8% | 0.0% | 18.2% | 15.4% |

| HE | Physical Activity | 30.0% | 100.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% |

| HE | Easing | 29.8% | 50.0% | 63.6% | 0.0% | 28.6% | 36.4% | 0.0% |

| SE | Accompaniment | 28.3% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Preference in Modal Choice | 26.4% | 15.8% | 50.0% | 16.7% | 36.8% | 22.2% | 16.7% |

| AC | Sidewalk Width | 25.2% | 20.0% | 27.3% | 33.3% | 30.0% | 27.3% | 13.3% |

| AT | Diversity | 23.3% | 100.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| AT | Deterioration | 22.7% | 44.4% | 11.8% | 20.0% | 22.2% | 17.6% | 20.0% |

| SE | Visibility | 21.2% | 23.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 53.8% | 0.0% | 50.0% |

| CO | Urban Furniture | 21.0% | 25.0% | 14.3% | 33.3% | 25.0% | 28.6% | 0.0% |

| AT | Density | 18.9% | 0.0% | 13.3% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Distance | 18.8% | 0.0% | 12.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| AC | Material | 18.0% | 14.3% | 33.3% | 12.5% | 14.3% | 33.3% | 0.0% |

| CO | Contamination | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 71.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 28.6% |

| AT | Sense of Belonging | 16.4% | 75.0% | 0.0% | 12.5% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 0.0% |

| CO | Noise | 14.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 54.5% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 18.2% |

| SA | Signalling | 14.7% | 26.7% | 0.0% | 41.7% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| AC | Continuity of the pedestrian infrastructure | 13.2% | 38.5% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Weather | 12.0% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 45.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.2% |

| AC | Architectural barriers and obstacles | 6.0% | 0.0% | 9.8% | 9.5% | 0.0% | 9.8% | 7.1% |

| SA | Friction with other Modes of Transport | 5.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.5% | 0.0% | 18.5% | 5.3% |

| SA | Wayfinding | 5.6% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Travel Time | 5.6% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Travel Time Availability | 3.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 23.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| SA | Traffic intensity | 3.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 11.1% | 0.0% |

| AT | Design | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| SE | Fear | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.3% |

| AC | Maintenance | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| AC | Walking Speed | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| SA | Traffic speed | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Slope | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Asp | Factor | % Average | % Negative Comments from Women | % Negative Comments from Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 35–64 | ≥65 | 18–34 | 35–64 | ≥65 | |||

| AC | Maintenance | 66.7% | 100.0% | 33.3% | 60.0% | 100.0% | 66.7% | 40.0% |

| SE | Fear | 46.9% | 56.3% | 33.3% | 68.8% | 43.8% | 66.7% | 12.5% |

| SA | Traffic intensity | 44.4% | 70.0% | 55.6% | 60.0% | 30.0% | 11.1% | 40.0% |

| SA | Friction with other Modes of Transport | 44.2% | 60.0% | 33.3% | 52.6% | 50.0% | 48.1% | 21.1% |

| SA | Traffic speed | 38.9% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 50.0% |

| SA | Wayfinding | 36.1% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 66.7% |

| AC | Architectural barriers and obstacles | 34.0% | 28.6% | 31.7% | 57.1% | 21.4% | 43.9% | 21.4% |

| CO | Slope | 33.7% | 16.7% | 100.0% | 42.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 42.9% |

| AC | Continuity of the pedestrian infrastructure | 32.9% | 15.4% | 100.0% | 25.0% | 15.4% | 0.0% | 41.7% |

| AC | Material | 32.0% | 42.9% | 16.7% | 75.0% | 28.6% | 16.7% | 12.5% |

| SE | Visibility | 31.4% | 23.1% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 15.4% | 50.0% | 0.0% |

| SA | Signaling | 29.7% | 13.3% | 0.0% | 41.7% | 6.7% | 100.0% | 16.7% |

| CO | Weather | 29.7% | 62.5% | 16.7% | 36.4% | 37.5% | 25.0% | 0.0% |

| AC | Walking Speed | 29.2% | 50.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 0.0% |

| AT | Density | 27.8% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 66.7% | 0.0% | 46.7% | 33.3% |

| AT | Diversity | 26.7% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Distance | 24.6% | 40.0% | 62.5% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Preference in Modal Choice | 24.5% | 36.8% | 5.6% | 66.7% | 15.8% | 22.2% | 0.0% |

| CO | Travel Time | 23.6% | 16.7% | 16.7% | 25.0% | 25.0% | 33.3% | 25.0% |

| AT | Deterioration | 20.9% | 11.1% | 17.6% | 20.0% | 11.1% | 35.3% | 30.0% |

| AT | Design | 20.5% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 64.3% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 28.6% |

| AT | Sense of Belonging | 20.1% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 62.5% | 0.0% | 22.2% | 25.0% |

| HE | Physical Activity | 20.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Travel Time Availability | 17.9% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Urban Furniture | 17.9% | 0.0% | 42.9% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 33.3% |

| CO | Noise | 16.8% | 16.7% | 14.3% | 27.3% | 0.0% | 42.9% | 0.0% |

| AC | Sidewalk Width | 16.8% | 10.0% | 13.6% | 53.3% | 10.0% | 13.6% | 0.0% |

| CO | Vegetation | 12.7% | 0.0% | 27.3% | 15.4% | 0.0% | 18.2% | 15.4% |

| CO | Contamination | 11.1% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% |

| SE | Accompaniment | 5.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Departure Time | 4.8% | 21.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| HE | Easing | 3.6% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| CO | Shade | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Lambas, M.E.; Alonso, A.; Ramírez-Saiz, A.; Pereira, A. These Boots Are Made for Walking: A Qualitative Study on the Perceived Barriers to Pedestrian Mobility in Madrid. Future Transp. 2023, 3, 111-132. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp3010008

López-Lambas ME, Alonso A, Ramírez-Saiz A, Pereira A. These Boots Are Made for Walking: A Qualitative Study on the Perceived Barriers to Pedestrian Mobility in Madrid. Future Transportation. 2023; 3(1):111-132. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp3010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Lambas, M. Eugenia, Andrea Alonso, Alba Ramírez-Saiz, and Andrés Pereira. 2023. "These Boots Are Made for Walking: A Qualitative Study on the Perceived Barriers to Pedestrian Mobility in Madrid" Future Transportation 3, no. 1: 111-132. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp3010008

APA StyleLópez-Lambas, M. E., Alonso, A., Ramírez-Saiz, A., & Pereira, A. (2023). These Boots Are Made for Walking: A Qualitative Study on the Perceived Barriers to Pedestrian Mobility in Madrid. Future Transportation, 3(1), 111-132. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp3010008