Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfalls of an Underrecognized Entity with Favorable Prognosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Radiologic and Endoscopic Assessment

2.2. Histopathological Processing

2.3. Ancillary Techniques

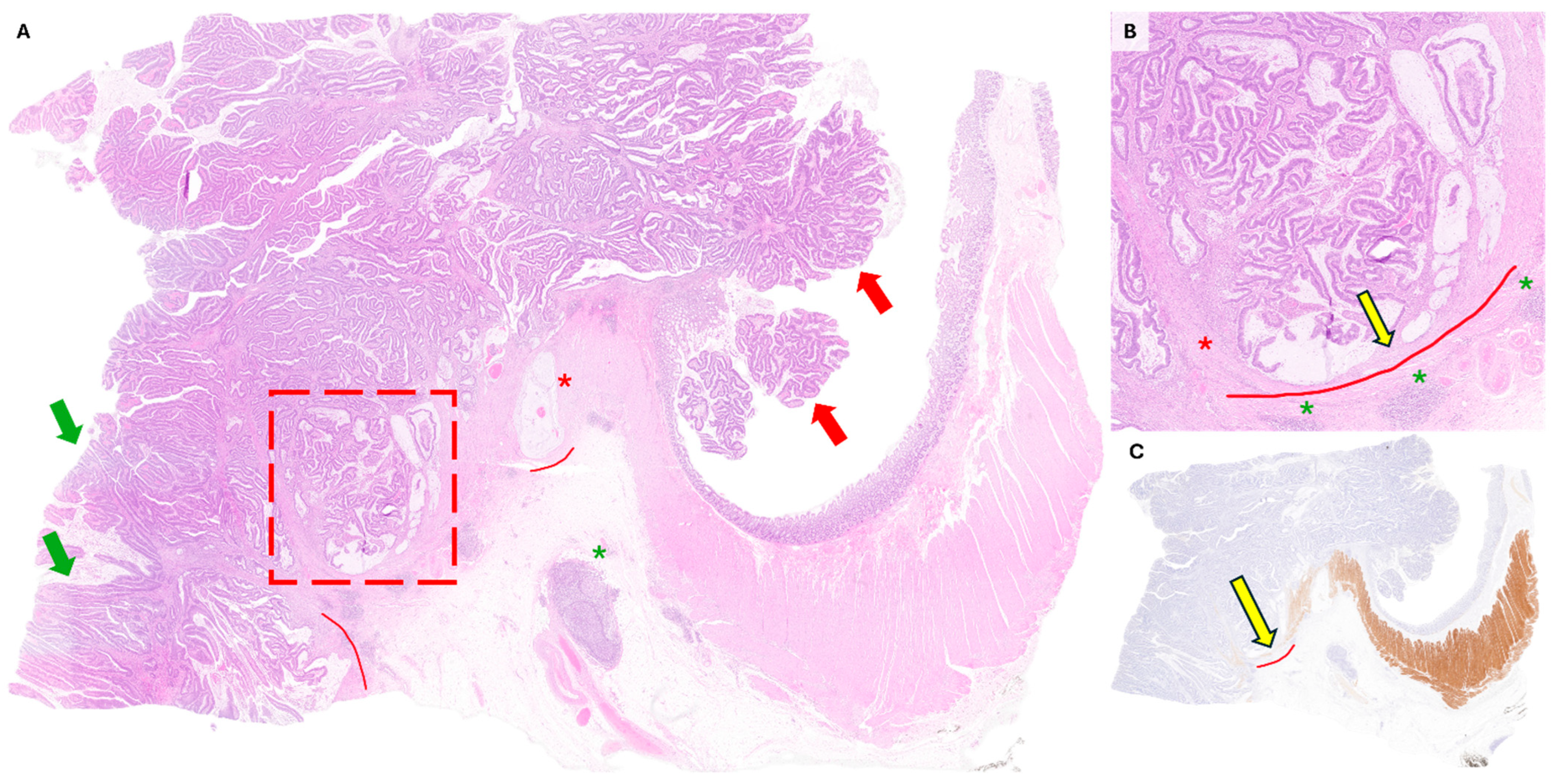

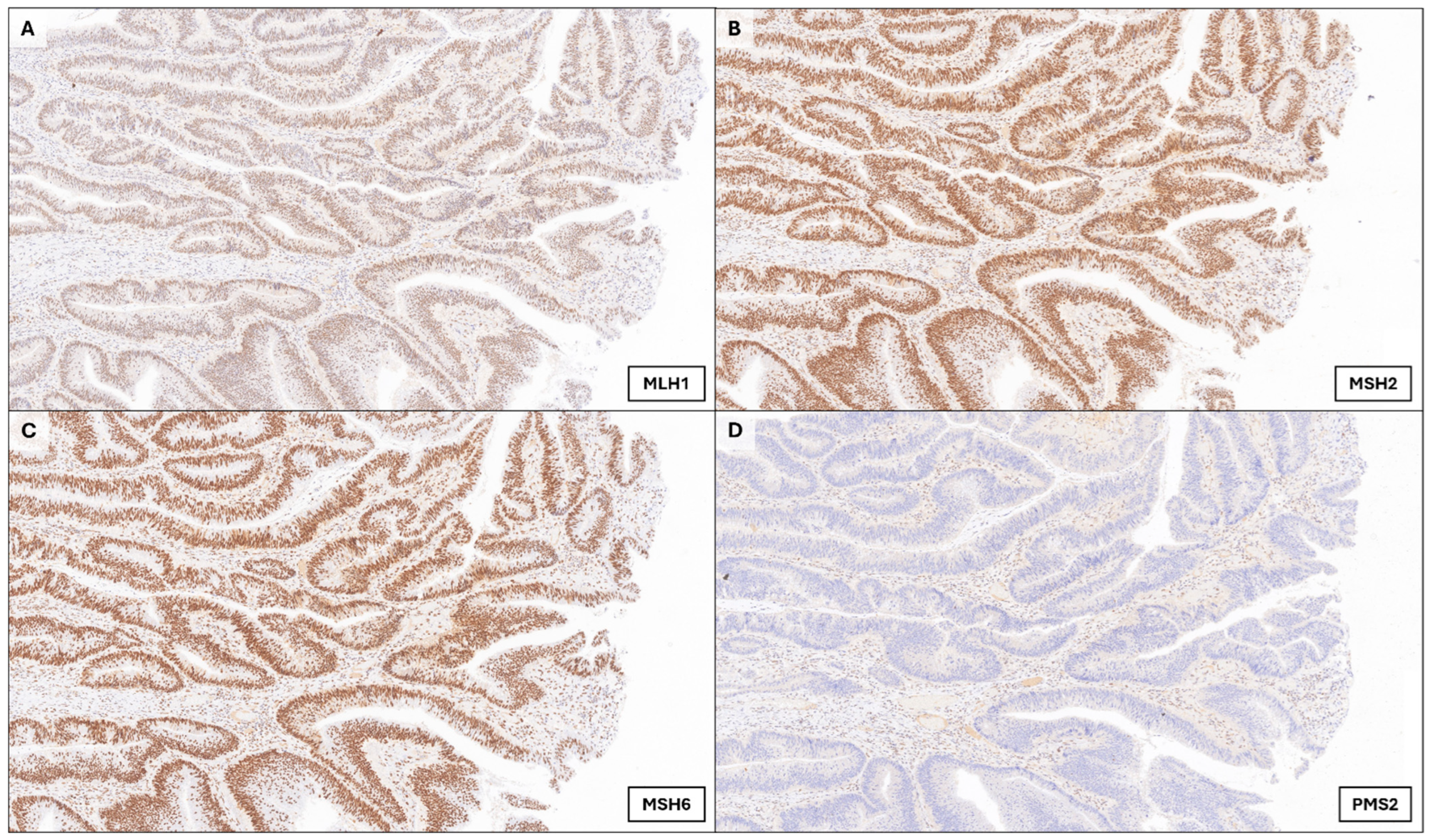

3. Case Presentation

4. Discussion

4.1. Tips and Clues to Avoid Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma Misdiagnosis

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, H.; Heisser, T.; Cardoso, R.; Hoffmeister, M. Reduction in colorectal cancer incidence by screening endoscopy. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R.S.; Cates, J.M.M.; Washington, M.K.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Coffey, R.J.; Shi, C. Adenoma-like adenocarcinoma: A subtype of colorectal carcinoma with good prognosis, deceptive appearance on biopsy and frequent KRAS mutation. Histopathology 2015, 68, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, T.S.; Kaplan, P.A. Villous Adenocarcinoma of the Colon and Rectum. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004, 28, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.A.; Yanagisawa, A.; Kato, Y. Histologic phenotypes of colonic carcinoma in Sweden and in Japan. Anticancer Res. 1998, 18, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, J.P.; Edmonston, T.B.; Chaille-Arnold, L.M.; Burkholder, S. Invasive papillary adenocarcinoma of the colon. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, I.A.; Bauer, P.S.; Liu, J.; Chatterjee, D. Adenoma-like adenocarcinoma: Clinicopathologic characterization of a newly recognized subtype of colorectal carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2020, 107, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remo, A.; Fassan, M.; Vanoli, A.; Bonetti, L.R.; Barresi, V.; Tatangelo, F.; Gafà, R.; Giordano, G.; Pancione, M.; Grillo, F.; et al. Morphology and Molecular Features of Rare Colorectal Carcinoma Histotypes. Cancers 2019, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa-Zamora, P.; García-Solano, J.; García-García, F.; Turpin, M.d.C.; Trujillo-Santos, J.; Torres-Moreno, D.; Oviedo-Ramírez, I.; Carbonell-Muñoz, R.; Muñoz-Delgado, E.; Rodriguez-Braun, E.; et al. Expression profiling shows differential molecular pathways and provides potential new diagnostic biomarkers for colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 132, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, E.R.; Vogelstein, B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990, 61, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungwirth, J.; Urbanova, M.; Boot, A.; Hosek, P.; Bendova, P.; Siskova, A.; Svec, J.; Kment, M.; Tumova, D.; Summerova, S.; et al. Mutational analysis of driver genes defines the colorectal adenoma: In situ carcinoma transition. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Song, B.; Kim, K.; Yokoyama, S. Colorectal cancers with a residual adenoma component: Clinicopathologic features and KRAS mutation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology theory: Cancer as multidimensional spatiotemporal "unity of ecology and evolution" pathological ecosystem. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1607–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.; Lindor, N.M.; Burgart, L.J.; Smalley, R.; Leontovich, O.; French, A.J.; Goldberg, R.M.; Sargent, D.J.; Jass, J.R.; Hopper, J.L.; et al. Isolated Loss of PMS2 Expression in Colorectal Cancers: Frequency, Patient Age, and Familial Aggregation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 6466–6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. Version 1. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_ceg.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Yao, T.; Kajiwara, M.; Kouzuki, T.; Iwashita, A.; Tsuneyoshi, M. Villous tumor of the colon and rectum with special reference to roles of p53 and bcl-2 in adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Pathol. Int. 1999, 49, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.; Mohanty, P.; Lenka, A.; Sahoo, N.; Agrawala, S.; Panigrahi, S.K. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Evaluation of CDX2 and Ki67 in Colorectal Lesions with their Expression Pattern in Different Histologic Variants, Grade, and Stage of Colorectal Carcinomas. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2021, 9, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisac, J.; Burgos, A.; Méndez, M. Adenoma-like adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyaval, F.; Fariña-Sarasqueta, A.; Boonstra, J.J.; Heijs, B.; Morreau, H. Recognition of pseudoinvasion in colorectal adenoma using spatial glycomics. Front. Med. 2024, 10, 1221553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, B.; Xu, B. Recent advances of pathomics in colorectal cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1094869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, I.A.; Bauer, P.S.; Liu, J.; Chatterjee, D. Intraepithelial tumour infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with absence of tumour budding and immature/myxoid desmoplastic reaction, and with better recurrence-free survival in stages I-III colorectal cancer. Histopathology 2021, 78, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saridaki, Z. Prognostic and predictive significance of MSI in stages II/III colon cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6809–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, N.J.; Cruise, M.; Tam, A.; Wicks, E.C.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Taube, J.M.; Blosser, R.L.; Fan, H.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.S.; et al. The Vigorous Immune Microenvironment of Microsatellite Instable Colon Cancer Is Balanced by Multiple Counter-Inhibitory Checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subtype | Key Architecture & Cytology | Invasion Front (Desmoplasia/Budding) | Typical Molecular Profile (MMR/MSI; Drivers) | Usual Site | Prognosis/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoma-like adenocarcinoma (ALAC) | Villiform/tubulovillous pattern; bland/low-grade cytology, deceptively “adenoma-like” | Pushing/expansile border, mild desmoplasia, absent/low budding | Not infrequently dMMR; KRAS mutations relatively common, BRAF/CIMP uncommon | Any (often right colon) | Early stage, low nodal burden; favorable outcomes after R0 resection; superficial biopsies often underestimate invasion |

| Conventional adenocarcinoma (NOS, well-differentiated) | Tubular ± villous; variable atypia | Typically infiltrative with desmoplasia; budding variable | Mixed: MSS or MSI; APC/KRAS/TP53 common | Any | Prognosis largely stage-driven |

| Serrated adenocarcinoma | Serrated glands, eosinophilic cytoplasm; may mimic traditional serrated lesions | Often infiltrative; mucinous areas frequent | MSI-H when MLH1 methylated; BRAF mutation and CIMP-high common | Proximal colon | Can show worse stage-adjusted survival vs. NOS in some series |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | ≥50% extracellular mucin pools with overt malignant epithelium | Infiltrative; tumor budding variable | Enriched for dMMR/MSI-H; KRAS frequent, variable BRAF | Proximal colon | Response to standard chemo may differ; outcomes vary with stage/MSI |

| Medullary carcinoma | Solid sheets, vesicular nuclei; prominent lymphoid infiltrate; pushing border | Pushing; budding typically low | Almost always MSI-H/dMMR combined with BRAF mutation; frequent PD-L1 expression | Proximal colon | Favorable stage-adjusted outcomes; immune-rich microenvironment |

| Micropapillary adenocarcinoma | Tight morula-like clusters in retraction spaces | Marked lymphovascular invasion; early nodal spread | Usually MSS; drivers variable | Any (often left colon) | Adverse prognosis |

| Variable | Details/Values at Presentation |

|---|---|

| Age/Sex | 81 yo/Male |

| Comorbidities | Former smoker (~60 pack-years; quit 3 years ago); Hypertension; COPD; ischemic heart disease; chronic kidney disease, prior abdominal surgery (segmental colectomy for polyp; cholecystectomy; umbilical/epigastric hernia repair; prostatectomy); cataracts; vertebrobasilar TIA 6 y ago; ECOG performance status 1 |

| Pharmacotherapy | Aspirin 100 mg; amlodipine 5 mg; bisoprolol 2.5 mg; furosemide 40 mg; omeprazole 40 mg; solifenacin 5 mg; fesoterodine 4 mg; pregabalin 25 mg; risperidone 2 mg; trazodone 100 mg |

| Leukocytes (WBC) | 15.0 × 109/L (88% neutrophils) |

| RBC | 3.40 × 1012/L |

| Hemoglobin | 10.5 g/dL |

| MCV | 92 fL |

| Platelets | 405 × 109/L |

| Glucose | 115 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.20 mg/dL |

| Sodium | 133 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 4.9 mmol/L |

| Bilirubin (total) | 1.3 mg/dL |

| Albumin | 3.2 g/dL |

| INR | 1.10 |

| aPTT | 31 s |

| CRP | 110 mg/L |

| LDH | 280 U/L |

| CEA | 2.1 ng/mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agüera-Sánchez, A.; Peña-Ros, E.; Martínez-Martínez, I.; García-Molina, F. Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfalls of an Underrecognized Entity with Favorable Prognosis. Onco 2025, 5, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5030039

Agüera-Sánchez A, Peña-Ros E, Martínez-Martínez I, García-Molina F. Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfalls of an Underrecognized Entity with Favorable Prognosis. Onco. 2025; 5(3):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgüera-Sánchez, Alfonso, Emilio Peña-Ros, Irene Martínez-Martínez, and Francisco García-Molina. 2025. "Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfalls of an Underrecognized Entity with Favorable Prognosis" Onco 5, no. 3: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5030039

APA StyleAgüera-Sánchez, A., Peña-Ros, E., Martínez-Martínez, I., & García-Molina, F. (2025). Adenoma-like Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfalls of an Underrecognized Entity with Favorable Prognosis. Onco, 5(3), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5030039