A Regional Experience of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumours: A Retrospective Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Primary Management

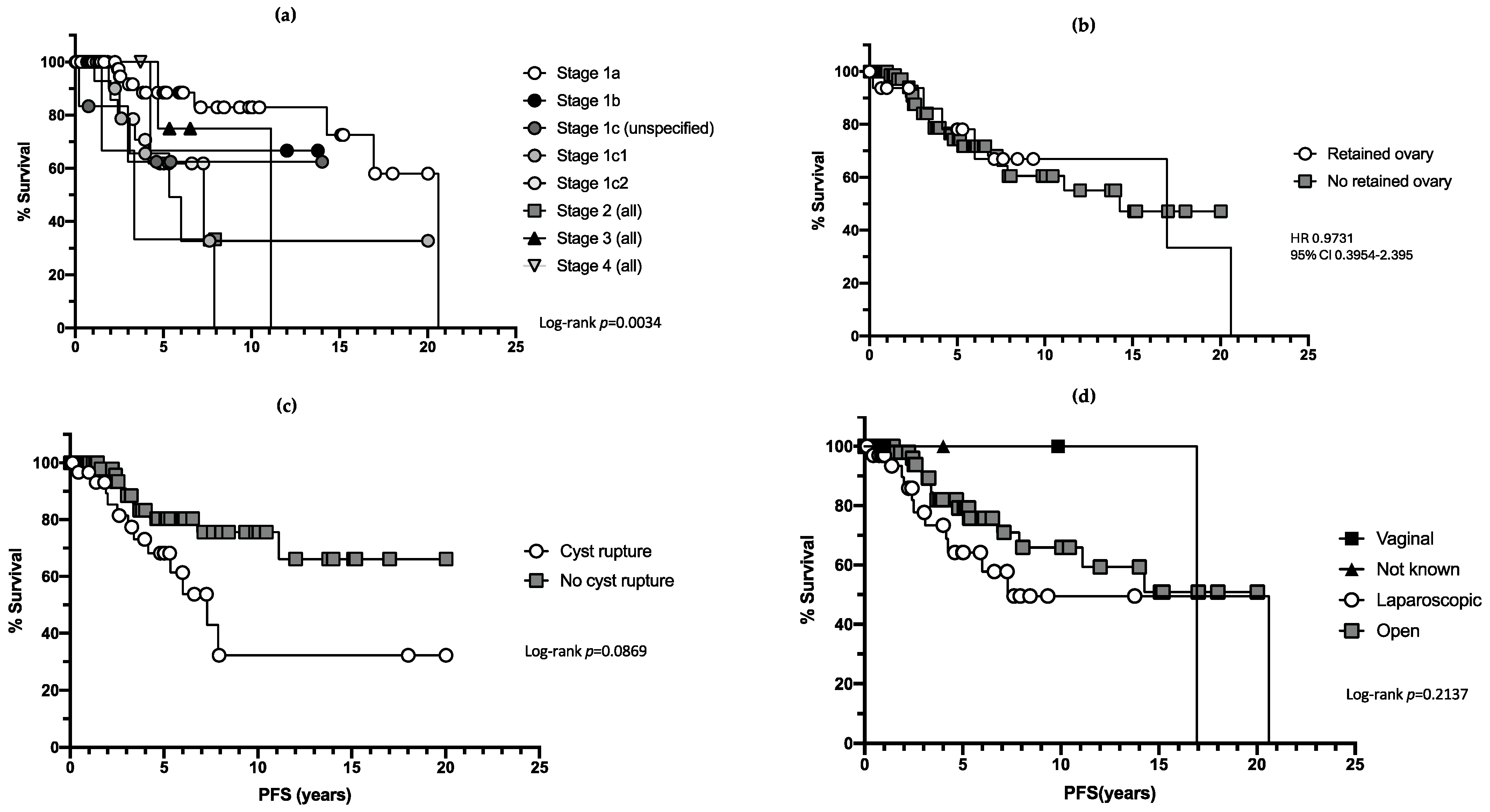

3.2. Recurrence

3.3. Surgical Complications

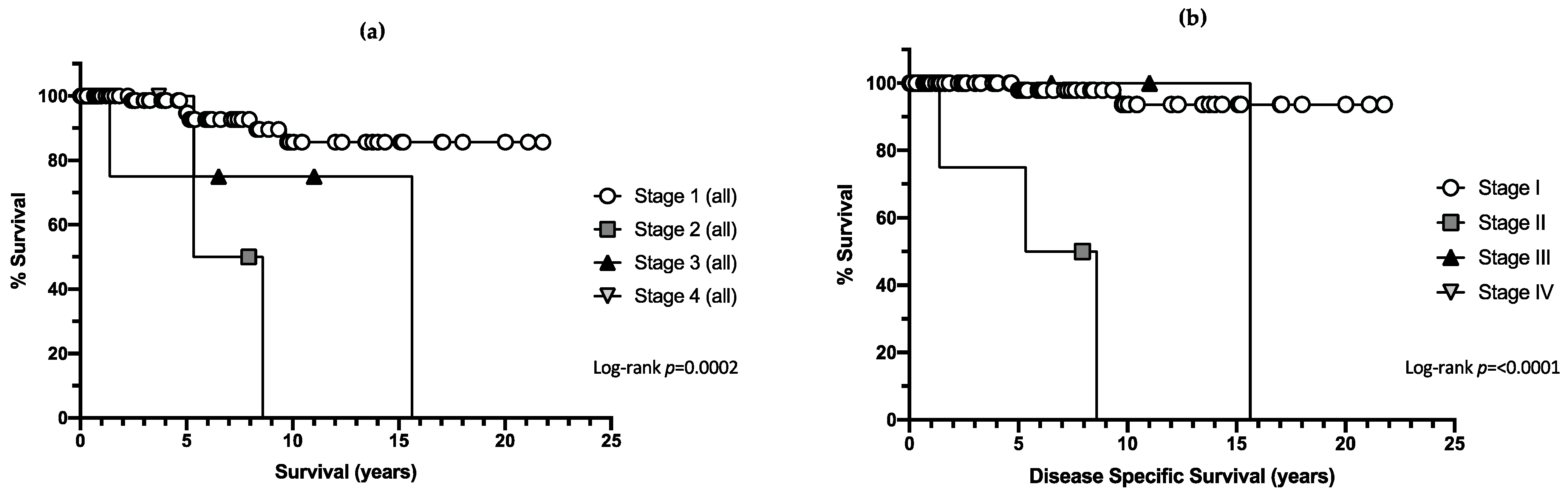

3.4. Mortality

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gurumurthy, M.; Bryant, A.; Shanbhag, S. Effectiveness of different treatment modalities for the management of adult-onset granulosa cell tumours of the ovary (primary and recurrent). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2018, CD006912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrall, M.; Paley, P.; Pizer, E.; Garcia, R.; Goff, B. Patterns of spread and recurrence of sex-cord stromal tumours of the ovary. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2011, 122, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uygun, K.; Aydiner, A.; Saip, P.; Basaran, M.; Tas, F.; Kocak, Z.; Dincer, M.; Topuz, E. Granulosa cell tumour of the ovary: Retrospective analysis of 45 cases. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 26, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangili, G.; Sigismondi, C.; Gadducci, A.; Cormio, G.; Scollo, P.; Tateo, S.; Ferrandina, G.; Candiani, M.; Lorusso, D. Outcome and Risk Factors for Recurrence in Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors: A MITO-9 Retrospective Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamini, A.; Ferrandina, G.; Candiani, M.; Cormio, G.; Giorda, G.; Lauria, R.; Perrone, A.; Scarfone, G.; Breda, E.; Saverese, A.; et al. Laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of stage I adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: Results from the MITO-9 study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Jin, K.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.; Nam, J. Surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy in the management of patients with adult granulosa cell tumours of the ovary. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasioudis, D.; Kanniinen, T.; Holcomb, K. Prevalence of lymph node metastasis and prognostic significance of lymphadenectomy in apparent early-stage malignant ovarian sex cord-stromal tumours. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Brown, J.; Harter, P.; Provencher, D.M.; Fong, P.C.; Maenpaa, J.; Ledermann, J.; Emons, G.; Rigaud, D.; Glasspool, R.; et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for ovarian sex cord stromal tumours. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H. Can adjuvant chemotherapy improve the prognosis of adult ovarian granulosa cell tumors? A narrative review. Medicine 2022, 101, e29062. [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Morice, P.; Lorusoo, D.; Prat, J.; Oaknin, A.; Pautier, P.; Colombo, N.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, IV1–IV18. Available online: https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)31689-8/fulltext (accessed on 7 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Cao, D.; Jia, C.; Huang, H.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Pan, L.; Shen, K.; Xiang, Y. Analysis of oncologic and reproductive outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery in apparent stage I adult ovarian granulosa cell tumours. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 151, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamini, A.; Cormio, G.; Ferrandina, G.; Lorusso, D.; Giorda, G.; Scarfone, G.; Bocciolone, L.; Raspagliesi, F.; Tateo, S.; Cassani, C.; et al. Conservative surgery in stage I adult type granulosa cells tumours of the ovary: Results from the MITO-9 study. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2019, 154, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ou, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, S.; Li, B. Characteristics and treatment results of recurrence in adult type granulosa cell tumour of ovary. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, G.; Groeneweg, J.; Hooft, L.; Zweemer, R.; Witteveen, P. Response to Systemic Therapies in Ovarian Adult Granulosa Cell Tumors: A Literature Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasukawa, M.; Matsuo, K.; Matsuzaki, S.; Dainty, L.; Sugarbaker, P. Management of recurrent granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: Contemporary literature review anda proposal of hyperthermic intraperitoeal chemotherapy as novel therapeutic option. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meurs, H.; Van Lonkhuijzen, L.; Limpens, J.; Van der Velden, J.; Buist, M. Hormone therapy in ovarian granulosa cell tumours: A systematic review. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Tang, M.; O’Connell, R.; Sjoquist, A.; Clamp, A.; Millan, D.; Nottley, S.; Lord, R.; Mullassery, V.; Hall, M.; et al. A phase 2 study of anastrozole in patients with oestrogen receptor and/progesterone receptor positive recurrent metastatic granulosa cell tumours/sex-cord stromal tumours of the ovary: The PARAGON/ANZGOG 0903 trial. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2021, 163, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pectasides, D.; Pectasides, E.; Psyrri, A. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2008, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkkila, A.; Haltia, U.; Tapper, J.; MConechy, M.; Huntsman, D.; Heikinheimo, M. Pathogenesis and treatment of adult-type granulosa cell tumour of the ovary. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Clement, K.; Hillard, T.; Sassarini, J.; Ratnavelu, N.; Baker-Rand, H.; Bowen, R.; Davies, M.; Edey, K.; Fernandes, A.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) and British Menopause Society (BMS) Guidelines Management of Menopausal Symptoms Following Treatment of Gynaecological Cancer. Available online: https://www.bgcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/BGCS-BMS-Guidelines-on-Management-of-Menopausal-Symptoms-after-Gynaecological-Cancer-09.09.24.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Miller, K.; McCluggage, W. Prognostic factors in ovarian adult granulosa cell tumour. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008, 61, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S.; Abdulfatah, E.; Thomas, S.; Al-wahab, Z.; Beydoun, R.; Morris, R.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Granulosa cell tumours: Novel predictors of recurrence in early-stage patients. Int. J. Gynaecol. Pathol. 2017, 36, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, E.; Taylor, A.; Andreou, A.; Ang, C.; Arora, R.; Attygalle, A.; Banerjee, S.; Bowen, R.; Buckley, L.; Burbos, N.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) ovarian, tubal and primary peritoneal cancer guidelines: Recommendations for practice update 2024. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 69–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotopoulou, C.; Hall, M.; Cruickshank, D.; Gabra, H.; Ganesan, R.; Hughes, C.; Kehoe, S.; Ledermann, J.; Morrison, J.; Naik, R.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) Epithelial Ovarian/Fallopian Tube/Primary Peritoneal Cancer Guidelines: Recommendations for Practice. Available online: https://www.bgcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/BGCS-Guidelines-Ovarian-Guidelines-2017.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Hall, M.; Roberts, C.; McCluggage, W.; Singh, N.; Paul, J.; Glasspoool, R.; Vazquez, I.; McNeish, I. EP714 RaNGO: A study to collect accessible information about patient with rare neoplasms of gynaecological origin in the UK. Int. J. Gynaecol. Cancer 2019, 29, A404–A405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Median Age at Diagnosis | 57 Years | 24–88 Years |

|---|---|---|

| Stage at diagnosis (FIGO 2014) | Ia | 60 (56.1%) |

| Ib | 3 (2.8%) | |

| Ic (all) | 34 (31.8%) | |

| Ic undetermined * | 6 (5.6%) | |

| Ic1 | 12 (11.2%) | |

| Ic2 | 16 (15.0%) | |

| Ic3 | 0 | |

| II | 5 (4.7%) | |

| III | 4 (3.7%) | |

| IV | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Primary surgical procedure | H+BSO+O+A | 29 (27.1%) |

| H+BSO | 28 (26.2%) | |

| USO | 25 (23.4%) | |

| BSO | 18 (16.8%) | |

| H+BSO+O+A+LND | 4 (3.7%) | |

| Ovarian cystectomy | 2 (1.9%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.9%) |

| Number of Patients | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of recurrences | 1 | 27 (25.2%) | |

| 2 | 15 (14.0%) | ||

| 3 | 9 (8.4%) | ||

| 4 | 3 (2.8%) | ||

| 5 | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| 6 | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| 7 | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| 8 | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Stage | Ia | 8/60 (13.3%) | p = 0.035 |

| Ib | 1/3 (33.3%) | ||

| Ic (all) | 14/34 (41.2%) | ||

| Ic undetermined | 2/6 (33.3%) | ||

| Ic1 | 5/12 (41.7%) | ||

| Ic2 | 7/16 (43.8%) | ||

| II | 2/5 (40.0%) | ||

| III | 2/5 (40.0%) | ||

| Primary procedure | Ovarian cystectomy | 2/2 (100%) | p < 0.001 |

| USO | 10/25 (40.0%) | ||

| BSO | 2/18 (11.1%) | ||

| H+BSO | 4/28 (14.3%) | ||

| H+BSO+O+A | 8/29 (27.6%) | ||

| H+BSO+O+A+LND | 0/4 | ||

| Other | 1/1 (100%) | ||

| Ovarian conservation | Yes | 6/17 (35.3%) | p = 0.386 |

| No | 21/90 (23.3%) | ||

| Route of surgery | Open | 14/66 (21.1%) | p = 0.406 |

| Laparoscopic | 12/37 (32.4%) | ||

| Vaginal | 0/2 | ||

| Intra-operative surgical spill | Spillage | 12/31 (38.7%) | p < 0.001 |

| No spillage | 10/70 (14.3%) |

| Number of Recurrences | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or More |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with recurrence | 27/107 (25.2%) | 15/107 (14.0%) | 9/107 (8.4%) | 3/107 (2.8%) |

| Median time to recurrence (months) | 40 (2–247) | 26 (11–47) | 17 (8–43) | 15 (7–15) |

| Site of recurrence | ||||

| Pelvis | 16/27 (59.3%) | 7/15 (46.7%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Pelvis and other | 7/27 (25.9%) | 6/15 (40.0%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Other | 2/27 (14.8%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Management | ||||

| surgery | 17/27 (63.0%) | 10/15 (66.7%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 2/3 (66.7%) |

| Chemotherapy | 1/27 (3.7%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 0/9 | 0/3 |

| Radiotherapy | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0/15 | 1/9 (11.1%) | 0/3 |

| Hormonal | 2/27 (7.4%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 0/3 |

| Surveillance | 4/27 (14.8%) | 0/15 | 1/9 (11.1%) | 0/3 |

| Best supportive care | 2/27 (7.4%) | 0/15 | 0/9 | 0/3 |

| Other | 0/27 | 1/15 (6.7%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Adjuvant treatment post-surgery | 5/17 (29.4%) | 4/10 (40.0%) | 3/5 (60.0%) | 0/3 |

| NMRD post-surgery | 14/17 (82.4%) | 8/10 (80.0%) | 3/5 (60.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) |

| Surgical complications (stage III Clavien or greater) | 1/17 (5.9%) | 1/10 (10.0%) | 0/5 | 0/5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moffatt, J.; Morrison, J.; Sundararajan, S.; Newhouse, R.; Atherton, L.; Frost, J.; Rolland, P.; Milford, K.; Edey, K.; Borley, J.; et al. A Regional Experience of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumours: A Retrospective Analysis. Onco 2025, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5020020

Moffatt J, Morrison J, Sundararajan S, Newhouse R, Atherton L, Frost J, Rolland P, Milford K, Edey K, Borley J, et al. A Regional Experience of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumours: A Retrospective Analysis. Onco. 2025; 5(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoffatt, Joanne, Jo Morrison, Srividya Sundararajan, Rebecca Newhouse, Laura Atherton, Jonathan Frost, Philip Rolland, Kirsty Milford, Katharine Edey, Jane Borley, and et al. 2025. "A Regional Experience of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumours: A Retrospective Analysis" Onco 5, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5020020

APA StyleMoffatt, J., Morrison, J., Sundararajan, S., Newhouse, R., Atherton, L., Frost, J., Rolland, P., Milford, K., Edey, K., Borley, J., Sanders, A., Walther, A., & Newton, C. (2025). A Regional Experience of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumours: A Retrospective Analysis. Onco, 5(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5020020