Remote Sensing-Based Mapping of Forest Above-Ground Biomass and Its Relationship with Bioclimatic Factors in the Atacora Mountain Chain (Togo) Using Google Earth Engine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

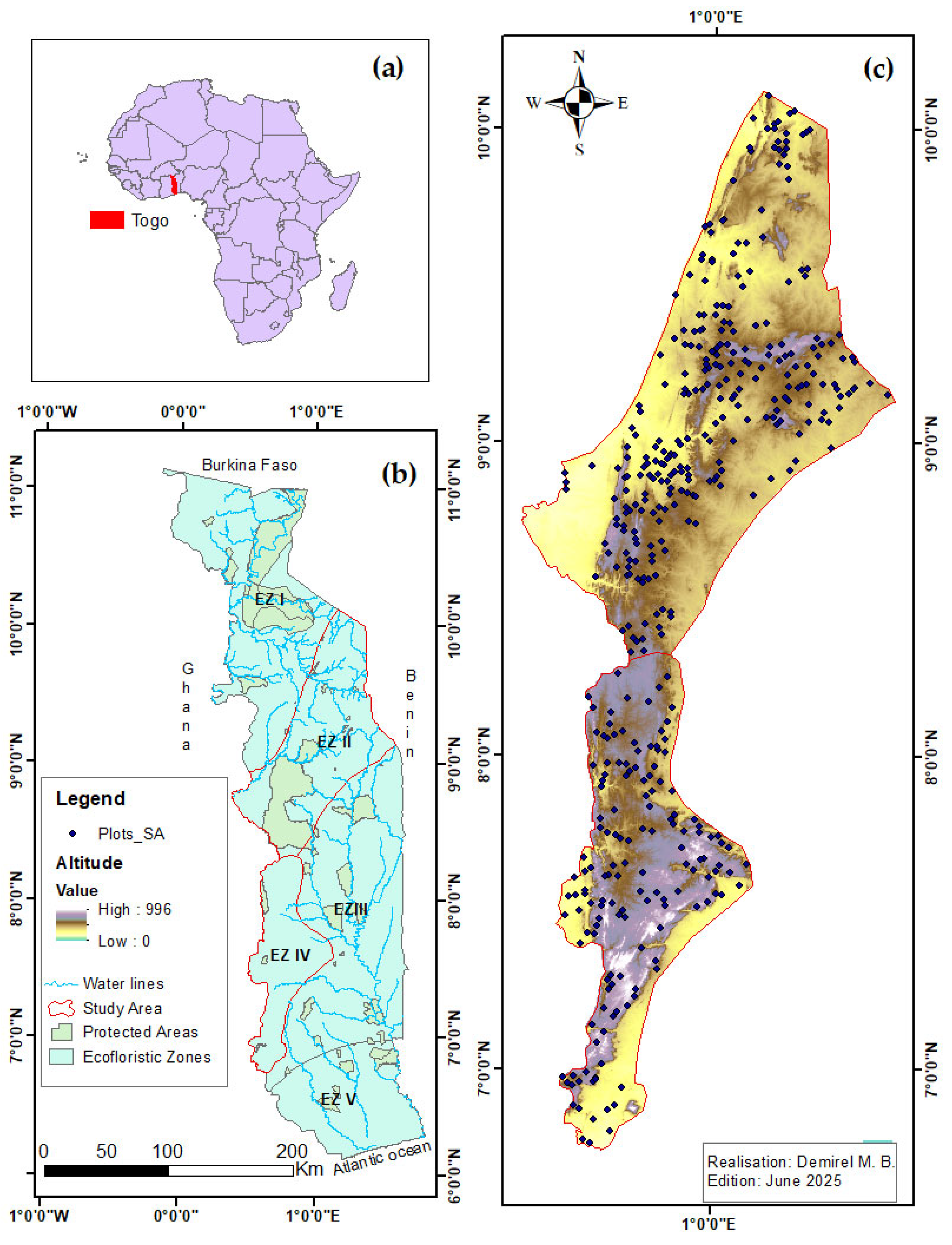

2.1. Study Area

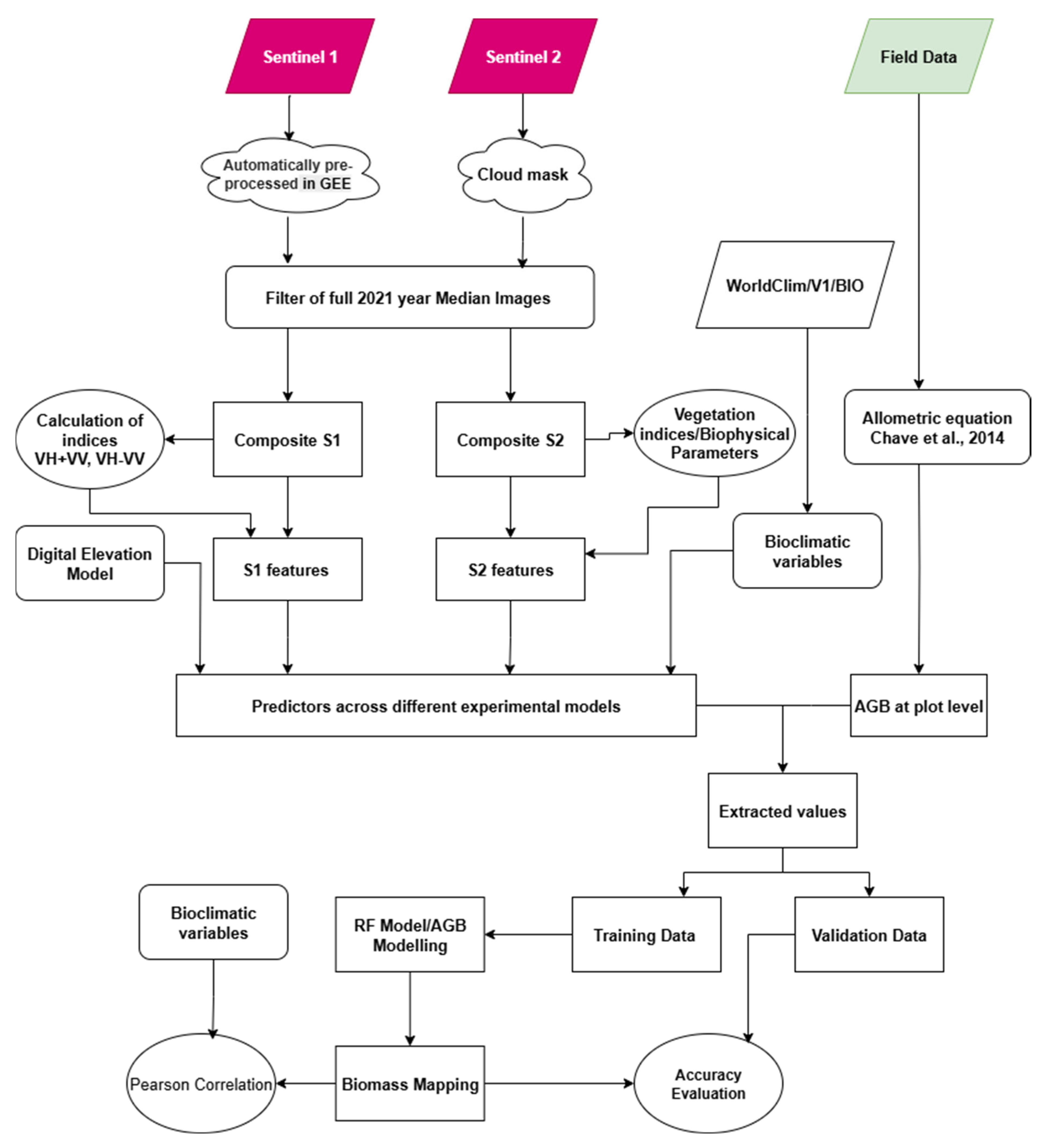

2.2. Satellite Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.3. Field Data

2.4. Bioclimatic Data

2.5. AGB Modeling

2.5.1. AGB Calculation from Field Data

- -

- AGB is the aboveground biomass (in kg);

- -

- is wood density (g/cm3);

- -

- D is the diameter at breast height (DBH) in cm;

- -

- H is the total tree height in meters;

2.5.2. Predictive Variables

2.5.3. Statistical or Machine Learning Modeling

2.5.4. Model Performance Assessment

2.5.5. Biomass Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Ground Truth

3.2. AGB Modeling Accuracy

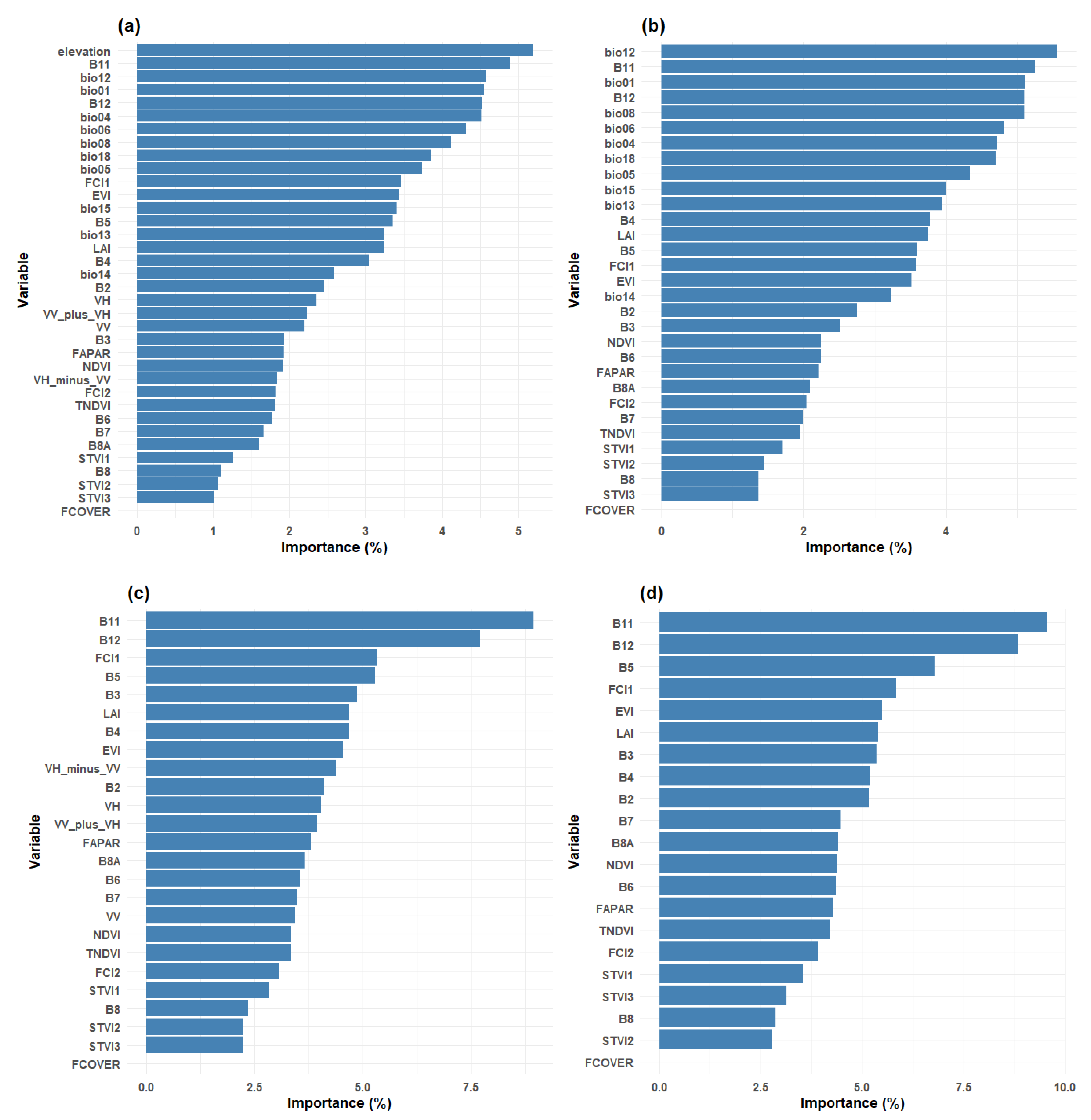

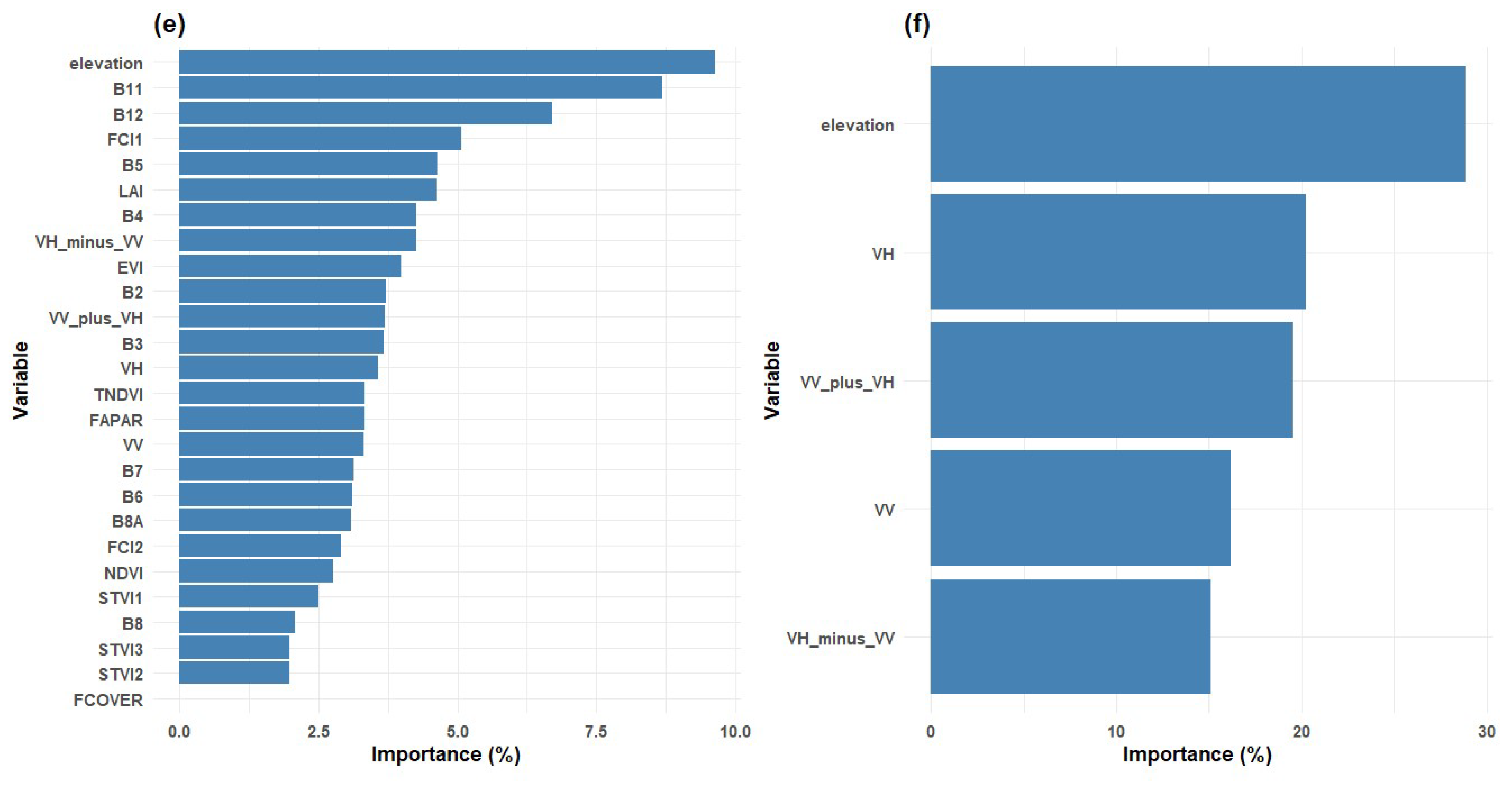

3.3. Relevant Variables in Different Experimental Models

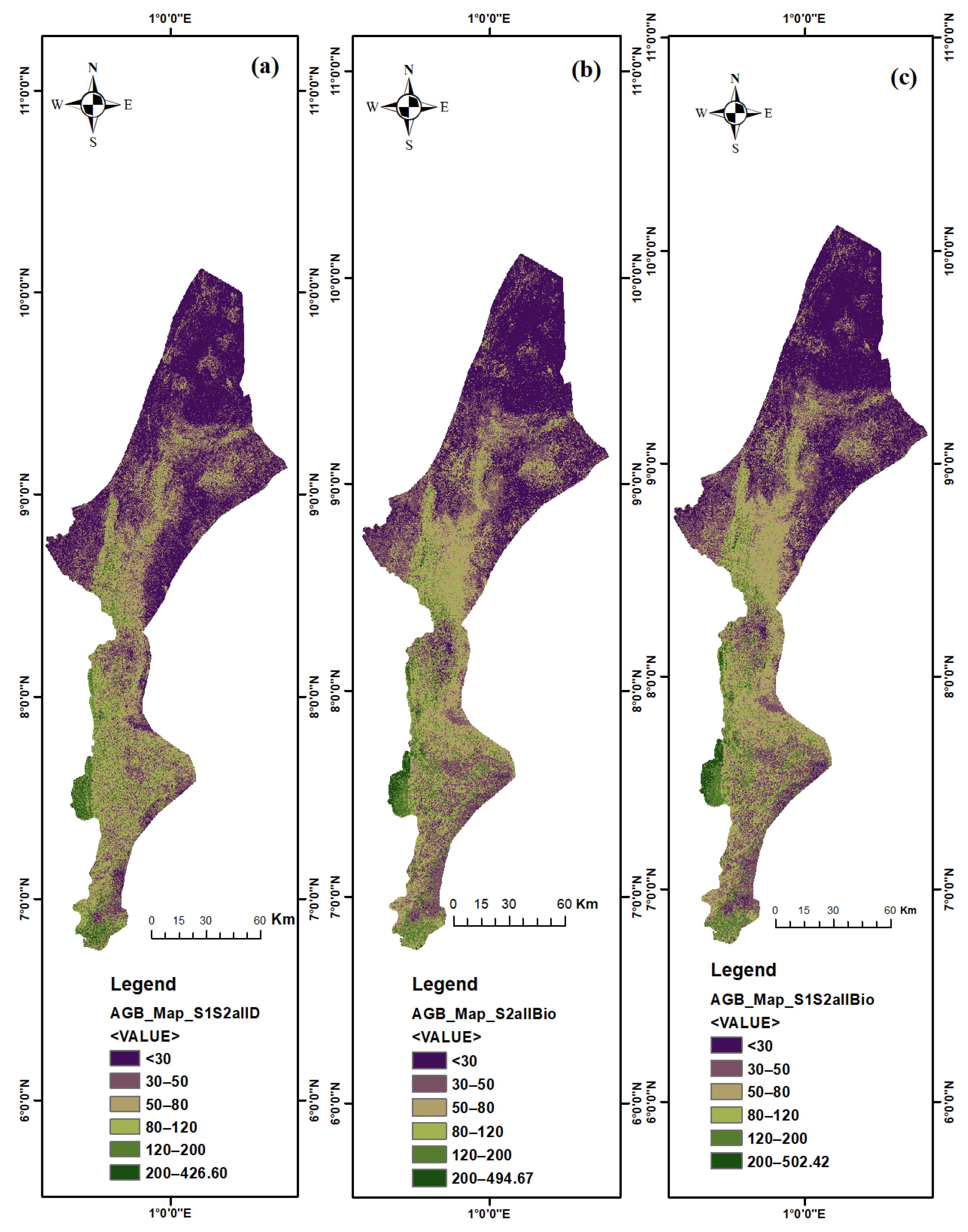

3.4. Spatial Mapping of AGB

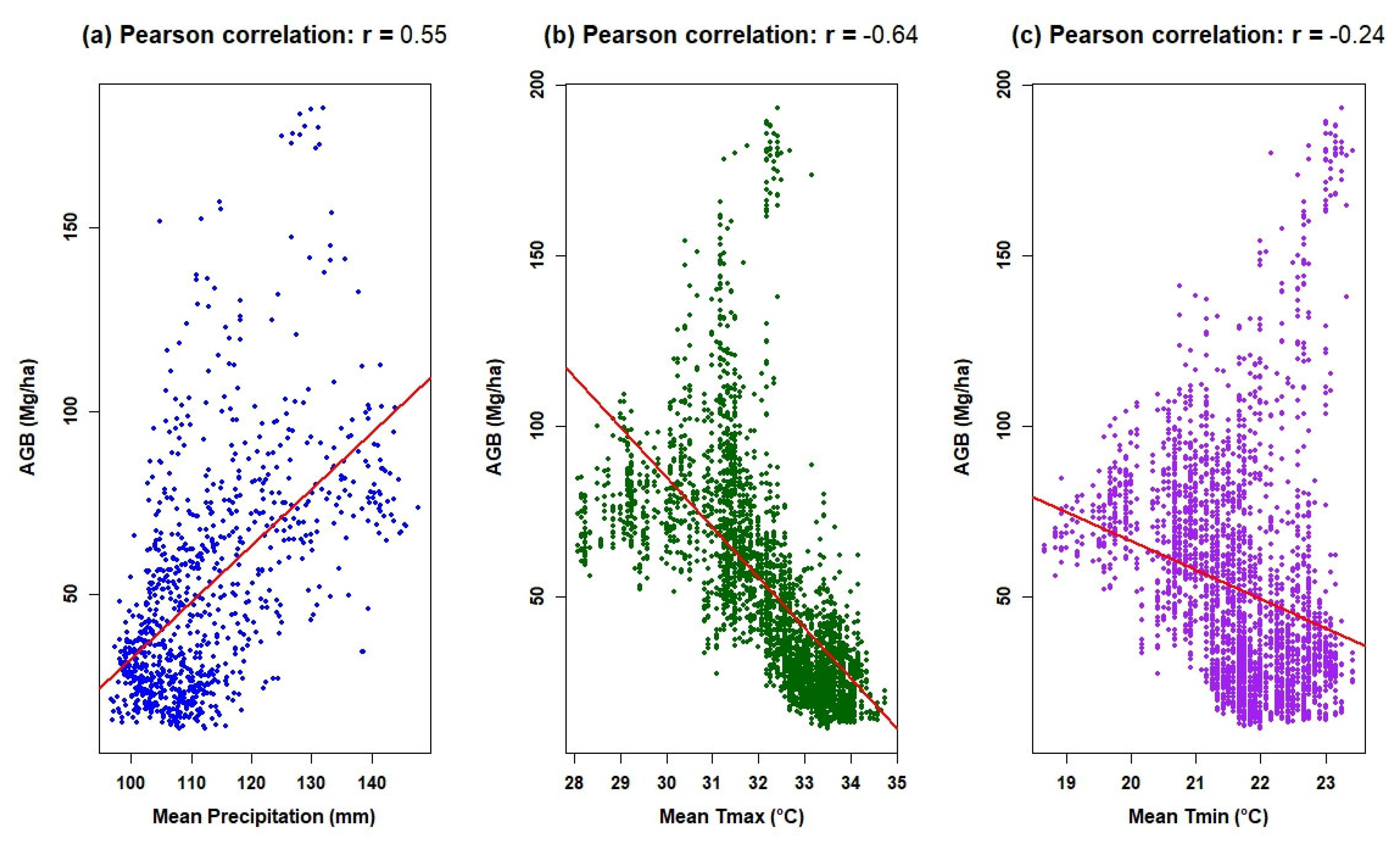

3.5. AGB and Bioclimatic Relationship

4. Discussion

4.1. AGB in Dense Forests

4.2. Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Environmental Variables in AGB Modeling

4.3. Spatial Distribution of AGB

4.4. Influence of Climatic Variables on AGB

4.5. AGB Mapping with GEE

4.6. Importance of This Study for Forest Management and Its Implications for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajasugunasekar, D.; Patel, A.; Devi, K.; Singh, A.; Selvam, P.; Chandra, A. An integrative review for the role of forests in combating climate change and promoting sustainable development. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 4331–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsri, H.K.; Konko, Y.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Abotsi, K.E.; Kokou, K. Changes in the West African forest-savanna mosaic, insights from central Togo. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avitabile, V.; Herold, M.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Asner, G.P.; Armston, J.; Ashton, P.S.; Banin, L.; Bayol, N. An integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, A.; Goetz, S.J.; Walker, W.; Laporte, N.; Sun, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Hackler, J.; Beck, P.; Dubayah, R.; Friedl, M. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Zoungrana, J.-B.B.; Dimobe, K.; Ouattara, B.; Vadrevu, K.P.; Tondoh, J.E. Above-ground biomass mapping in West African dryland forest using Sentinel-1 and 2 datasets-A case study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woegan, Y.A.; Akpavi, S.; Dourma, M.; Atato, A.; Wala, K.; Akpagana, K. Etat des connaissances sur la flore et la phytosociologie de deux aires protégées de la chaîne de l’Atakora au Togo: Parc National Fazao-Malfakassa et Réserve de Faune d’Alédjo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013, 7, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourma, M.; Batawila, K.; Guelly, K.A.; Bellefontaine, R.; Foucault, B.d.; Akpagana, K. La flore des forêts claires à Isoberlinia spp. en zone soudanienne au Togo Titre courant: Flore des forêts claires à Isoberlinia. Acta Bot. Gall. 2012, 159, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folega, F.; Woegan, Y.A.; Marra, D.; Wala, K.; Batawila, K.; Seburanga, J.L.; Zhang, C.-y.; Peng, D.-l.; Zhao, X.-h.; Akpagana, K. Long term evaluation of green vegetation cover dynamic in the Atacora Mountain chain (Togo) and its relation to carbon sequestration in West Africa. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, T.G.; Teixeira, R.F.; Figueiredo, M.; Domingos, T. The use of machine learning methods to estimate aboveground biomass of grasslands: A review. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.M.; Rosser, N.J.; Donoghue, D.N. Improving above ground biomass estimates of Southern Africa dryland forests by combining Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 282, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, G.V.; Balling, J.; Corona, P.; Mattioli, W.; Papale, D.; Puletti, N.; Rizzo, M.; Truckenbrodt, J.; Urban, M. Above-ground biomass prediction by Sentinel-1 multitemporal data in central Italy with integration of ALOS2 and Sentinel-2 data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2018, 12, 016008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immitzer, M.; Neuwirth, M.; Böck, S.; Brenner, H.; Vuolo, F.; Atzberger, C. Optimal input features for tree species classification in Central Europe based on multi-temporal Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolívar-Santamaría, S.; Reu, B. Detection and characterization of agroforestry systems in the Colombian Andes using sentinel-2 imagery. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Srinet, R.; Padalia, H. Mapping forest height and aboveground biomass by integrating ICESat-2, Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data using Random Forest algorithm in northwest Himalayan foothills of India. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendryk, Y. Fusing GEDI with earth observation data for large area aboveground biomass mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J. Estimating vegetation aboveground biomass in Yellow River Delta coastal wetlands using Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 imagery. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 87, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yin, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J. Aboveground Biomass Mapping in SemiArid Forests by Integrating Airborne LiDAR with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Time-Series Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmegne, T.D.; Latifi, H.; Ullmann, T.; Baumhauer, R.; Bayala, J.; Thiel, M. Estimation of aboveground biomass in agroforestry systems over three climatic regions in West Africa using sentinel-1, sentinel-2, ALOS, and GEDI data. Sensors 2022, 23, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimobe, K.; Kuyah, S.; Ouédraogo, K.; Tondoh, E.J.; Thiombiano, A. Aboveground Biomass in West African Semi-Arid Ecosystems: Structural Diversity, Taxonomic Contributions and Environmental Drivers. J. Sustain. Agric. 2025, 4, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laly, F.G.; Atindogbe, G.; Akpo, H.A.; Fonton, N.H. Estimation of aboveground biomass of savanna trees using quantitative structure models and close-range photogrammetry. Trees For. People 2025, 19, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, S.; Gao, H.; Sun, L.; Yan, G. Multi-Decision Vector Fusion Model for Enhanced Mapping of Aboveground Biomass in Subtropical Forests Integrating Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Miraglia, N.; Persichilli, C.; De Angelis, M.; Pilla, F.; Di Brita, A. Modelling of the above-ground biomass and ecological composition of semi-natural grasslands on the strenght of remote sensing data and machine learning algorithms. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ern, H. Die Vegetation Togos. Gliederung, Gefährdung, Erhaltung. Willdenowia 1979, 9, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Adjossou, K. Diversité, Structure et Dynamique de la Végétation Dans les Fragments de Forêts Humides du Togo: Les Enjeux pour la Conservation de la Biodiversité. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi, A.; Darestani, A.T.; Mostofi, N.; Fathi, M.; Amani, M. Improving forest above-ground biomass estimation using genetic-based feature selection from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data (case study of the Noor forest area in Iran). Kuwait J. Sci. 2024, 51, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Csaplovics, E. AGB estimation using Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 datasets. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Deering, D.; Schell, J.; Harlan, J.C. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Green Wave effect) of Natural Vegetation; Progress Report RSC 1978-1; Texas A&M Univ.: College Station, TX, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rezzouk, F.Z.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Kefauver, S.C.; Gutiérrez, N.A.; Aranjuelo, I.; Serret, M.D.; Araus, J.L. Remote sensing techniques and stable isotopes as phenotyping tools to assess wheat yield performance: Effects of growing temperature and vernalization. Plant Sci. 2020, 295, 110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.R., Jr.; Lautenschlager, L.F. Functional equivalence of spectral vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1984, 14, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Ward, A.D.; Lyon, J.G.; Merry, C.J. Thematic mapper vegetation indices for determining soybean and corn growth parameters. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1994, 60, 437–442. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.J.; Daughtry, C.S.; Russ, A.L. Robust forest cover indices for multispectral images. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2018, 84, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Búrquez, A.; Chidumayo, E.; Colgan, M.S.; Delitti, W.B.; Duque, A.; Eid, T.; Fearnside, P.M.; Goodman, R.C. Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 3177–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanne, A.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Coomes, D.; Ilic, J.; Jansen, S.; Lewis, S.; Miller, R.; Swenson, N.; Wiemann, M.; Chave, J. Global Wood Density Database: Dryad Digital Repository. 2009. Available online: https://datadryad.org/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.234 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Chave, J.; Coomes, D.; Jansen, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Swenson, N.G.; Zanne, A.E. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsri, H.K.; Kokou, K.; Abotsi, K.E.; Kokutse, A.D.; Cuni-Sanchez, A. Above-ground biomass and vegetation attributes in the forest-savannah mosaic of Togo, West Africa. Afr. J. Ecol. 2020, 58, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, M.; Espira, A. The influence of stand variables and human use on biomass and carbon stocks of a transitional African forest: Implications for forest carbon projects. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 351, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argamosa, R.J.L.; Blanco, A.C.; Baloloy, A.B.; Candido, C.G.; Dumalag, J.B.L.C.; Dimapilis, L.L.C.; Paringit, E.C. Modelling above ground biomass of mangrove forest using Sentinel-1 imagery. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre-Tojal, L.; Bastarrika, A.; Boyano, A.; Lopez-Guede, J.M.; Grana, M. Above-ground biomass estimation from LiDAR data using random forest algorithms. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 58, 101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folega, F.; Diwediga, B.; Guuroh, R.T.; Kperkouma, W.; AKPAGANA, K. Riparian and stream forests carbon sequestration in the context of high anthropogenic disturbance in Togo. Moroc. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 1, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jibrin, A.; Abdulkadir, A. Allometric models for biomass estimation in savanna woodland area, Niger State, Nigeria. WASET Int. J. Environ. Chem. Ecol. Geol. Geophys. Eng. 2015, 9, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- N’Gbala, F.N.G.; Guéi, A.M.; Tondoh, J.E. Carbon stocks in selected tree plantations, as compared with semi-deciduous forests in centre-west Côte d’Ivoire. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 239, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koranteng, A.; Adu-Poku, I.; Zawila-Niedzwiecki, T. Drivers of land use change and carbon mapping in the savannah area of Ghana. Folia For. Polonica. Ser. A For. 2017, 59, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakpama, W.; Amegnaglo, K.; Afelu, B.; Folega, F.; Batawila, K.; Akpagana, K. Biodiversité et biomasse pyrophyte au Togo. VertigO Rev. Électronique Sci. L’environnement 2019, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavasoli, N.; Arefi, H. Comparison of capability of SAR and optical data in mapping forest above ground biomass based on machine learning. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2020, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Xie, Q. A comprehensive comparison of machine learning and feature selection methods for maize biomass estimation using sentinel-1 SAR, sentinel-2 vegetation indices, and biophysical variables. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shao, Z.; Jiang, W.; Gao, H. Integrating Sentinel-1 and 2 with LiDAR data to estimate aboveground biomass of subtropical forests in northeast Guangdong, China. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafis, I.; Mallinis, G.; Siachalou, S.; Patias, P. Assessing the relationships between growing stock volume and Sentinel-2 imagery in a Mediterranean forest ecosystem. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 8, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinley, J.; Pickering, C.; Ndehedehe, C. Using vegetation and chlorophyll indices to model above ground biomass over time in an urban arboretum in subtropical queensland. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. 2024, 34, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Liang, J.; Liao, Y.; Ma, X. Co-pyrolysis of chlorella vulgaris and kitchen waste with different additives using TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Dávila, E.; Cayuela, L.; González-Caro, S.; Aldana, A.M.; Stevenson, P.R.; Phillips, O.; Cogollo, Á.; Penuela, M.C.; Von Hildebrand, P.; Jiménez, E. Forest biomass density across large climate gradients in northern South America is related to water availability but not with temperature. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, A.; Mermoz, S.; Le Toan, T.; Villard, L.; Mathieu, R.; Naidoo, L.; Asner, G.P. An above-ground biomass map of African savannahs and woodlands at 25 m resolution derived from ALOS PALSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 206, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSEED. Résultats Définitifs du RGPH-5 de Novembre 2022; Institut de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques et Démographiques-Togo: Lomé, Togo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nemani, R.R.; Keeling, C.D.; Hashimoto, H.; Jolly, W.M.; Piper, S.C.; Tucker, C.J.; Myneni, R.B.; Running, S.W. Climate-driven increases in global terrestrial net primary production from 1982 to 1999. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 300, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilouktime, B.; Fousséni, F.; Maza-esso, B.D.; Weiguo, L.; Hua Guo, H.; Kpérkouma, W.; Komlan, B. Monitoring the Net Primary Productivity of Togo’s Ecosystems in Relation to Changes in Precipitation and Temperature. Geomatics 2024, 4, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, P.B.; Brando, P.; Asner, G.P.; Field, C.B. Projections of future meteorological drought and wet periods in the Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13172–13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 329, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.T. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.; Wu, D.; Mao, W. Comparison of supervised machine learning methods to predict ship propulsion power at sea. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 245, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Toan, T.; Quegan, S.; Davidson, M.; Balzter, H.; Paillou, P.; Papathanassiou, K.; Plummer, S.; Rocca, F.; Saatchi, S.; Shugart, H. The BIOMASS mission: Mapping global forest biomass to better understand the terrestrial carbon cycle. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 2850–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data and Acquisition Period | Predictive Variable | Definition and Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-1 (1 January 2021–31 December 2021) | Polarization VH | Vertical transmit, horizontal receive |

| Polarization VV | Vertical transmit, vertical receive | |

| Product (VH + VV) | Sum of VH and VV backscatter values [12] | |

| Quotient (VH − VV) | Difference between VH and VV backscatter values [12] | |

| Sentinel-2 (1 January 2021–31 December 2021) | Band 2 | Blue band (490 nm) |

| Band 3 | Green band (560 nm) | |

| Band 4 | Red band (665 nm) | |

| Band 5 | Red Edge 1 (705 nm) | |

| Band 6 | Red Edge 2 (740 nm) | |

| Band 7 | Red Edge 3 (783 nm) | |

| Band 8 | NIR (842 nm) | |

| Band 8A | Narrow NIR (865 nm) | |

| Band 11 | SWIR 1 (1610 nm) | |

| Band 12 | SWIR 2 (2190 nm) | |

| Vegetation Indices and Biophysical Parameters (1 January 2021–31 December 2021) | NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index [29] |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index [30] | |

| TNDVI | Transformed NDVI [31] | |

| STVI1 | Soil-Adjusted Transformed VI 1 [32] | |

| STVI2 | Soil-Adjusted Transformed VI 2 [32] | |

| STVI3 | Soil-Adjusted Transformed VI 3 [32] | |

| FCI | Forest Canopy Index I [33] | |

| FCII | Forest Canopy Index II [33] | |

| LAI | LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| FCOVER | FCOVER | Fraction of Vegetation Cover |

| FAPAR | FAPAR | Fraction of Absorbed PAR |

| Terrain factor | Altitude | Elevation above mean sea level (in meters), derived from the NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model |

| Vegetation Type | Area_Ha | No_Plots | No_Trees | DBH_Mean | Height_Mean | Density | Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crops/Fallows | 5.53 | 44 | 863 | 21.94 ± 0.51 | 10.77 ± 0.20 | 686.75 ± 103.53 | 127 |

| Open forests/Wooded Savannas | 18.22 | 145 | 5648 | 18.71 ± 0.13 | 9.52 ± 0.06 | 8989.07 ± 746.50 | 158 |

| Dense forests | 16.34 | 130 | 4847 | 22.49 ± 0.24 | 11.93 ± 0.09 | 3857.12 ± 338.29 | 262 |

| Tree/Shrub Savannas | 12.82 | 102 | 2989 | 16.09 ± 0.14 | 7.92 ± 0.06 | 5946.42 ± 588.78 | 124 |

| Code | Bioclimatic Variable | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIO1 | Annual Mean Temperature | Average temperature over the year | °C |

| BIO12 | Annual Precipitation | Total precipitation over the year | mm |

| BIO4 | Temperature Seasonality | Standard deviation × 100 | % (relative index) |

| BIO15 | Precipitation Seasonality | Coefficient of variation of monthly precipitation | % |

| BIO5 | Max Temperature of Warmest Month | Highest average temperature in the warmest month | °C |

| BIO6 | Min Temperature of Coldest Month | Lowest average temperature in the coldest month | °C |

| BIO13 | Precipitation of Wettest Month | Total precipitation in the wettest month | mm |

| BIO14 | Precipitation of Driest Month | Total precipitation in the driest month | mm |

| BIO18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | Total precipitation in the warmest three-month period | mm |

| BIO8 | Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter | Average temperature during the wettest quarter | °C |

| Vegetation Type | Mean (Mg/ha) | SD | N | SE | CV | Min | Max | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crops/Fallows | 47.52 | 49 | 44 | 7.39 | 1.03 | 0.14 | 215.24 | 215.1 |

| Open forests/Wooded Savannas | 59.71 | 41.33 | 145 | 3.43 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 228.28 | 227.66 |

| Dense forests | 124.2 | 94.15 | 130 | 8.26 | 0.76 | 9 | 518.24 | 509.25 |

| Tree/Shrub Savannas | 25.38 | 20.68 | 102 | 2.05 | 0.82 | 1.22 | 122.28 | 121.06 |

| Experimented Model | Abbreviation | Associated Data/Objectives | R2 | MAE | RMSE | sMAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a): All SAR, optical, and bioclimatic data | S1S2allBio | Includes all available predictors (SAR, optical, bioclimatic) | 0.90 | 13.42 | 22.54 | 27.64 |

| (b): Optical and bioclimatic data only | S2allBio | Sentinel-2 optical data, vegetation indices, biophysical factors, and bioclimatic variables | 0.86 | 15.23 | 27.07 | 29.57 |

| (c): SAR and optical data | S1S2all | SAR and optical data only (no bioclimatic variables) | 0.54 | 30.49 | 48.87 | 47.22 |

| (d): Optical data only | S2all | Only Sentinel-2 data and its derived indices | 0.52 | 31.31 | 50.02 | 48.35 |

| (e): SAR, optical, and DEM data | S1S2allD | All predictors except bioclimatic variables (including DEM) | 0.66 | 26.71 | 42.07 | 43.44 |

| (f): SAR data only | S1all | Only Sentinel-1 polarizations, backscatter values, and elevation | 0.42 | 36.02 | 54.86 | 56.66 |

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.77 | −0.09 | 0.18 | −0.58 | −0.72 | 0.59 | 0.7 | 0.76 | 0.21 |

| Tmax | −0.24 | −0.24 | −0.26 | −0.25 | −0.23 | −0.20 | −0.20 | −0.19 | −0.19 | −0.22 | −0.24 | −0.23 |

| Tmin | −0.06 | −0.15 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.20 | −0.18 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bawa, D.M.-e.; Folega, F.; Dahan, K.S.; Stoleriu, C.C.; Badjaré, B.; Šinžar-Sekulić, J.; Huang, H.; Kperkouma, W.; Komlan, B. Remote Sensing-Based Mapping of Forest Above-Ground Biomass and Its Relationship with Bioclimatic Factors in the Atacora Mountain Chain (Togo) Using Google Earth Engine. Geomatics 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics6010008

Bawa DM-e, Folega F, Dahan KS, Stoleriu CC, Badjaré B, Šinžar-Sekulić J, Huang H, Kperkouma W, Komlan B. Remote Sensing-Based Mapping of Forest Above-Ground Biomass and Its Relationship with Bioclimatic Factors in the Atacora Mountain Chain (Togo) Using Google Earth Engine. Geomatics. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleBawa, Demirel Maza-esso, Fousséni Folega, Kueshi Semanou Dahan, Cristian Constantin Stoleriu, Bilouktime Badjaré, Jasmina Šinžar-Sekulić, Huaguo Huang, Wala Kperkouma, and Batawila Komlan. 2026. "Remote Sensing-Based Mapping of Forest Above-Ground Biomass and Its Relationship with Bioclimatic Factors in the Atacora Mountain Chain (Togo) Using Google Earth Engine" Geomatics 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics6010008

APA StyleBawa, D. M.-e., Folega, F., Dahan, K. S., Stoleriu, C. C., Badjaré, B., Šinžar-Sekulić, J., Huang, H., Kperkouma, W., & Komlan, B. (2026). Remote Sensing-Based Mapping of Forest Above-Ground Biomass and Its Relationship with Bioclimatic Factors in the Atacora Mountain Chain (Togo) Using Google Earth Engine. Geomatics, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics6010008