1. Introduction

Climate change is an increasingly pressing issue today, as a number of human activities are intensifying its impact [

1]. In addition to the fact that the effects of climate change are often exaggerated [

2], it is important to know that it is one of the most significant environmental challenges. It causes an increase in global average temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice, rising sea levels, and affects basic human needs such as food and water [

3,

4,

5]. The observed warming is consistent with the expected effects of greenhouse gases, which significantly affect the planet’s biodiversity and cause various environmental and health problems [

6]. Climate change and biodiversity are interdependent. Increased global average temperatures due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, as well as extreme and unpredictable weather patterns, are key manifestations of climate change, which are significantly affecting the planet’s biodiversity and further threatening the delicate balance of ecosystems [

7]. Some species are already at remarkable risk, which is expected to increase significantly in the future [

8]. The extinction of species that play a role in fundamental ecosystem processes can disrupt and lead to the collapse of the ecological system [

9]. Global-scale estimates predict a large decline in biodiversity due to climate change, which is more significant than the loss currently observed and much higher than the rate of species extinction documented in the study of fossils [

10].

Clasping-leaved pondweed (

Potamogeton perfoliatus L.), spiked watermilfoil (

Myriophyllum spicatum L.), and holly-leaved naiad (

Najas marina L.) serve as the primary underwater macrophytes present in Lake Balaton and the Kis-Balaton area [

11]. In Hungary, submerged macrophytes become established in lakes and water bodies with low water flow during the summer months (June to September) [

12].

Water lily (

Nuphar lutea (L.)

Smith) of the family

Nymphaceae is a floating-leaved macrophyte. The species inhabits lakes, small reservoirs, oxbow lakes, as well as small rivers and streams. It prefers depths of approximately 2.5 m. The plant has a thick rhizome that is firmly anchored in the sediment by its roots [

13].

Algae are a polyphyletic group of mostly photosynthetic organisms [

14]. They are found in all aquatic environments of the entire planet [

15]. Although they play an important role in natural ecosystems, the overgrowth of some species of algae, such as diatoms, leads to algal blooms, which are considered a process with a negative impact [

16].

Unmanned aerial vehicles are becoming increasingly popular in many areas of military and civilian life, especially in those where direct human involvement is difficult or dangerous [

17,

18]. This presents a valuable opportunity to enhance efficiency and reduce costs while maintaining the quality of data [

19]. The development of UAVs has progressed from pilot-controlled operation to fully autonomous flight, offering a more user-friendly and reliable means of performing various tasks [

20]. Drones can also be effectively utilized for monitoring and surveying operations, which consequently reduces the need for human resources in these occupations. They represent an investment in themselves, and their ability to expedite work completion while requiring fewer personnel makes them a financially advantageous option across numerous sectors. Furthermore, as drone technology continues to develop and become more common, the cost of these tools and related technologies is likely to decrease and become accessible to more users [

21].

Remote sensing technology can also be effectively applied in nature conservation areas. Protected areas aim to conserve biodiversity, preserve ecosystems, and maintain natural heritage [

22]. They play a fundamental role in conservation, but the transfer of resources is not always sufficient to cope with everyday tasks and unforeseen events [

23]. In order to legally maintain their status, protected areas must also comply with national and international conventions [

24]. Therefore, cost-effective, versatile, and practical solutions are needed to ensure the conservation requirements. These include a wide range of natural processes, technological developments, and new methods, or innovative applications of technologies [

25]. The detection of change and its characterization is an essential step for monitoring [

26]. Mexican researchers [

27] utilized active and passive remote sensing data in conjunction with machine learning techniques (Random Forest and XGBoost) to model Aboveground Biomass (AGB) in temperate forests of central Mexico, subsequently conducting a comparison of the estimations with those derived from a conventional method such as linear regression. University of Botswana staff [

28] used a DJI Phantom 4 drone for efficient large-scale topographic mapping.

Drones can be equipped with various sensors, which should be selected according to the work to be performed. Guimarães et al. [

29] successfully used an UAV equipped with an RGB sensor to produce ultra-high-resolution digital products that can be used to identify areas affected by forest fires in the Brazilian Cerrado. Recordings can be captured across various spectral ranges and subsequently compared, as Musungu et al. [

30] did. Their study evaluated the capacity of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) visible-near infrared (VIS-NIR) data collected in spring and summer to pinpoint the spectral attributes of eleven Fynbos wetland species within a seep wetland. The distances obtained from spectral data analysis showed specific clusters of plant species, indicating which species were distinguishable from one another. Karthigesu et al. [

31] combined the analysis of RGB and multispectral images. In their study, they integrated structural, textural, and spectral metrics obtained from an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) utilizing Red–Green–Blue (RGB) and multispectral (MS) imagery to predict individual tree parameters through a random forest regression model within a diverse mixed conifer–broadleaf forest.

The availability of high- and ultra-high-resolution images and the development of artificial intelligence-based algorithms have significantly improved the applicability and accuracy of surface classification. Information about surface cover plays a key role in land use planning or monitoring activities in a given area. By using ultra-high-resolution data in space and time, investigators can quickly obtain reliable information about the state of the environment and monitor changes. Researchers use a variety of image classification methods on the images to classify the surface and the objects on it, and to extract information contained in the images. Identifying individual areas and delimiting different parts serves as the basis for thematic mapping of the surface and detecting and analyzing changes [

32,

33]. There is currently a rise in remote sensing datasets with various scene semantics, making it difficult for computer vision methods to accurately categorize scene images for scene classification [

34].

The following objectives were set during the study:

Quantification of monthly surface cover dynamics of a lake and six channels using UAV imaging.

Examination of the relationship between surface cover and the main meteorological elements.

Examination of the relationship between surface cover and different flow conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Sample Area

The site of the investigations was the Kísérleti-lake and its immediate surroundings in the area of Phase I (Hídvégi-lake) in the summer of 2024. The study area is located on the Kis-Balaton wetland in Hungary, which is one of the most sensitive areas in Europe, and together with Lake Balaton, it forms one of the most unique ecosystems in the world. In the examined area near the shore, macrophytes, reeds, and cattails are the dominant plant species. Around the lake, groups of the tall goldenrod (

Solidago gigantea) are growing, serving as the basis of several investigations in the Kis-Balaton. Moving away from the coast, weedy grasses [

35] form the dominant vegetation, which are gradually replaced by woody stands. There are also flow-supporting channels to the east of the lake (

Figure 1). These have different flow conditions. Thus, in addition to meteorological elements, the influencing effect of the flow could be observed. The size of the lake and the flow-supporting channels were also determined during data processing. This was performed with QGIS (3.40.9 ‘Bratislava’) software. The surface area of the examined water bodies was comparatively small. Therefore, satellite remote sensing images are unsuitable for their analysis. The lake had the largest water surface (15.46 ha); however, a resolution of several meters per pixel would have posed a problem even in this case. This was particularly true for the channels, as none of them exceeded one hectare. The surface area of the smallest flow-supporting channel was 0.17 ha, the largest 0.78 ha. The smallest ones would have been just a few pixels, which would not have provided any relevant information.

2.2. The Process of Aerial Photography

During aerial survey, the area usually flown over is based on pre-prepared flight plans, thus avoiding errors due to human factors. Route planning is critical in UAV operations. This requires considering the physical limitations of the flight, the safety of the route, and the feasibility. This involves determining a feasible flight path from the starting point to the destination.

The completed flight plan can be saved and re-executed at any time. This is especially important if the goal is multi-temporal, ultra-high-resolution imaging. By executing the recording at the same height, on the same route, and at the same flight speed each time, it is possible to get the same result from a given area during every recording. This way, TIFF files generated from individual images, which show the entire sample area, can be effectively compared with each other, and detecting and illustrating individual changes will be much easier. TIFF is a large, lossless raster file. The word lossless is used because the original image data remains even if the file is copied, re-saved, or compressed multiple times. This property distinguishes it from other file types.

Aerial surveys were conducted monthly, preferably within the first ten days of each month. This was chiefly contingent upon the prevailing weather conditions. Flights were not conducted on days characterized by strong winds, precipitation, or fog.

The aerial photographs were taken with several types of drones (DJI Mavic 3, Phantom 4 Pro, M30, and M300) and different sensors (multispectral, thermal). The flights occurred concurrently under high sun conditions, preferably between 11 am and 3 pm, and at three different altitudes. In general, it can be said that by reducing the flight altitude, the geometric resolution of the images, the number of images taken, and the flight time also increased (

Table 1).

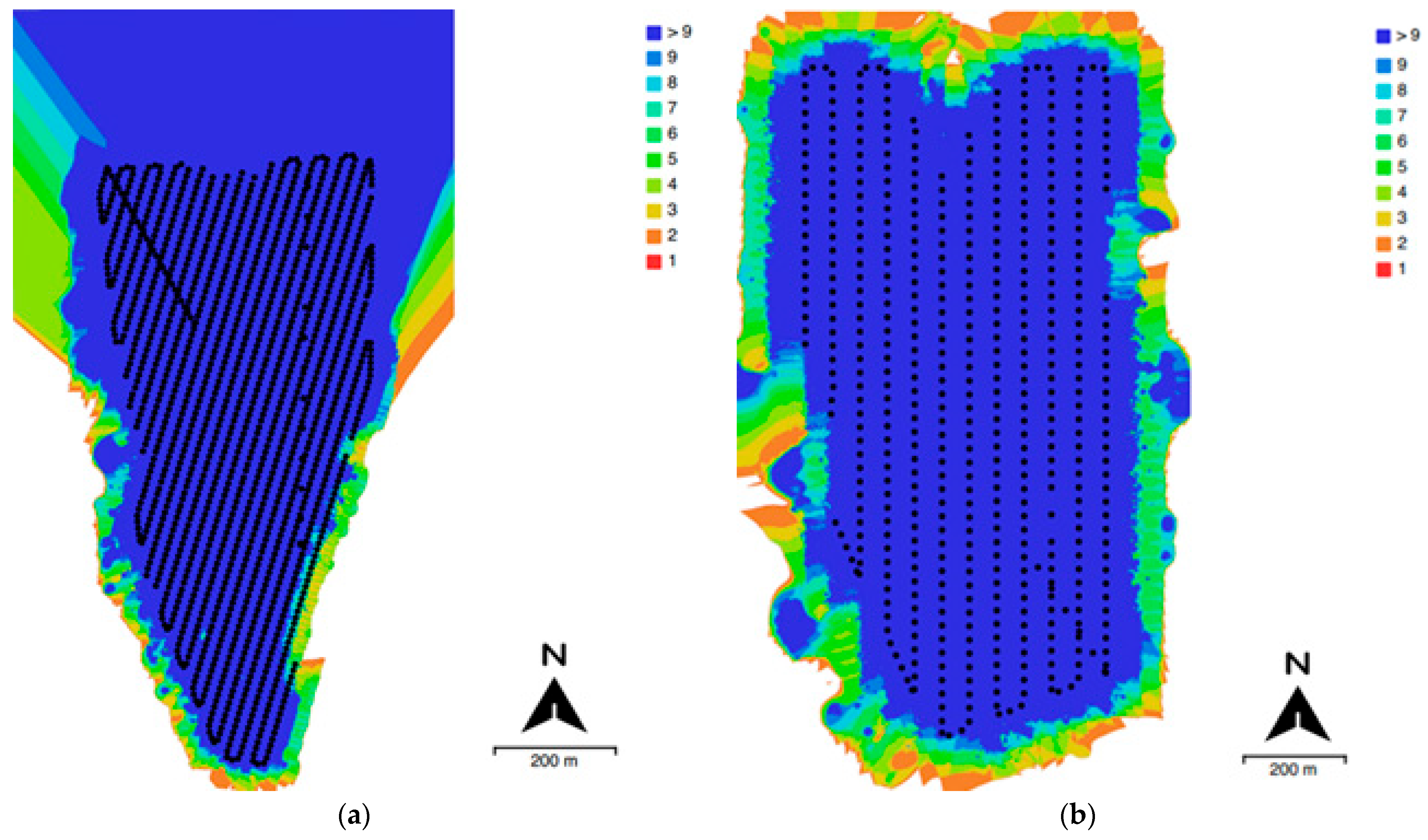

The resolution of the images captured was excellent at all three flight altitudes. No qualitative differences were observed between them during the classification process. The images captured at 150 m were more manageable in terms of storage and processing, and therefore, the work was conducted using them. For the accurate stitching of the aerial photographs, overlaps were needed between the individual images, as the software was able to assemble the individual images based on them (

Figure 2).

2.3. Processing of Aerial Photographs

The quality of the uploaded images is of utmost importance. Regarding the alignment operation, it is important to note that blurry photos can adversely impact the accuracy of the alignment results. During the processing of the completed time-series images, the alignment was performed using Agisoft Metashape 2.0.3 software. Metashape enables the creation and visualization of a dense point cloud model, which serves as the foundation for subsequent processing stages such as mesh construction, digital elevation model development, and orthophoto generation. As a result, an ultra-high-resolution orthophoto was created, which covers the entire examined area, but has the high geometric resolution of the individual aerial photographs. The orthophoto—as the most frequently used final product—should be produced based on the dense cloud. Creating a model from a dense point cloud requires a longer processing time; however, the resulting model will exhibit significantly higher quality [

36]. The end result is a time-series image set that effectively allows changes to be observed. Time-series orthophotos were created for each recording, followed by pre-processing and processing. The completed time-series GeoTIFF files were rectified using Adobe PhotoShop 26.9.0 (2025) software; that is, the images were aligned onto a common plane. Subsequently, image details pertinent to the research were separated. This selection can be applied to each layer, ensuring that the same basis is used during the examinations, where the essential changes are made. The ROIs were digitized manually. The definition was established when the coastal vegetation was at its densest. This made it possible to ensure that no inappropriate shoreline vegetation parts were included in any of the layers. Subsequently, the sections of the image that were pertinent to the analysis were extracted according to the selections.

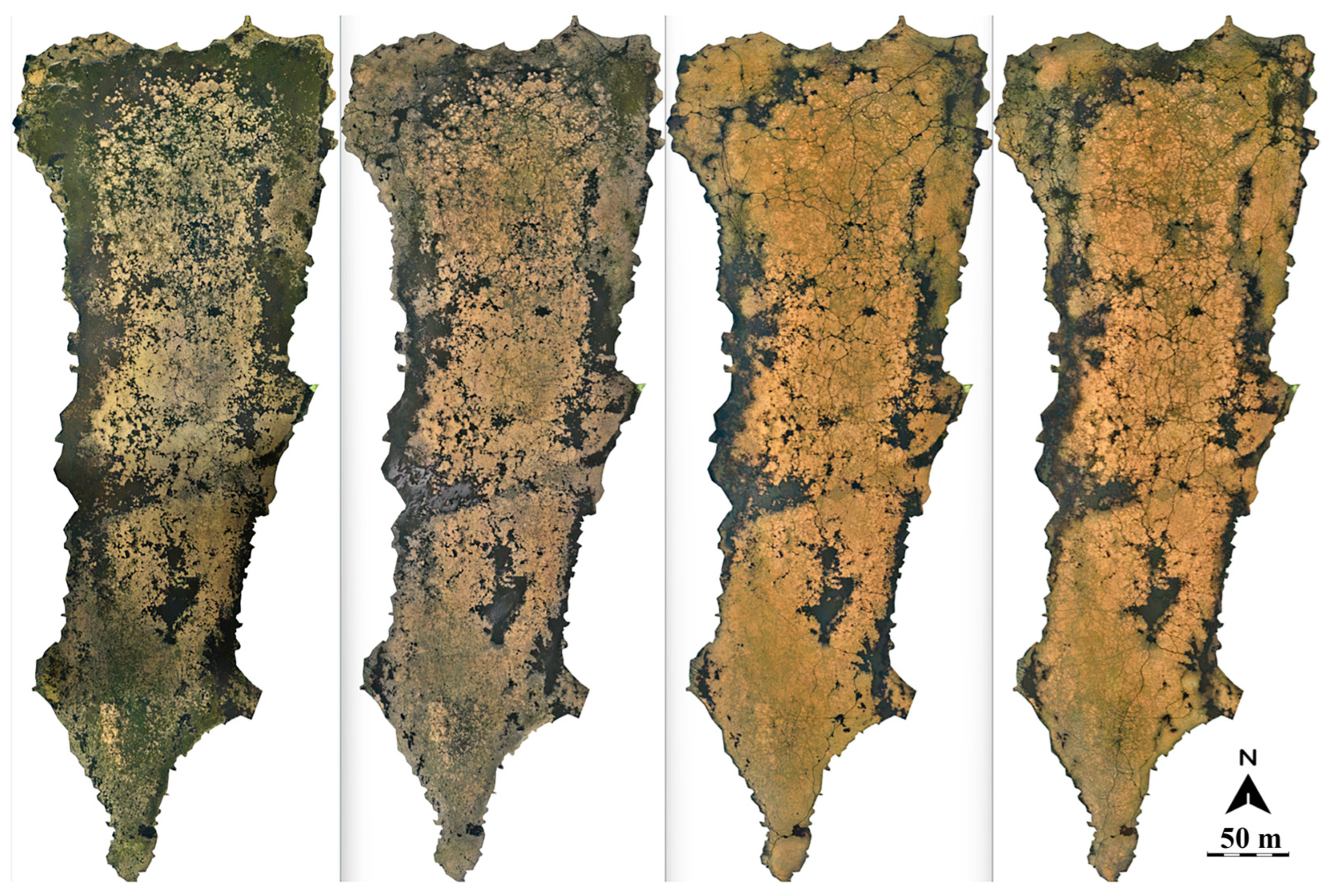

Figure 3 shows that the vegetation reaching the water surface will increase from May to July in 2024. This remained largely unchanged even in August. Although the approximate changes were visible in these images, they had to be quantified, which required classification.

The image segments extracted from the original GeoTIFF were arranged in chronological order. The various channels and lake surfaces served as the foundation for the classifications. The information content of the images was previously examined by applying the Shannon entropy [

37,

38]. The data obtained through this method can facilitate the optimal execution of UAS operations best suited for subsequent image processing tasks, such as classification, segmentation, and index analysis [

39]. In addition, spectral fractal dimension (SFD) measurement was also performed. The definition of spectral fractal dimension can be applied to the measured data, like a function [

40,

41]. The information content (entropy), spectral fractal structure, and entropy-weighted spectral fractal structure, as functions of the integration time, supported the success of physiologically justified sampling [

42].

2.4. Implementing Image Classification

The images were classified using MultiSpec [

43] software. MultiSpec is an image processing software that analyzes image data interactively. This typically includes multispectral data produced by satellites, as well as processing hyperspectral image data produced by UAVs. In addition, it can be used to classify any image, since pixel-based classification based on different colors can also be effectively applied to them. The MultiSpec “Version 2024.05.16 64-bit” was used to classify different images.

The software enables users to sample specific areas of the image and assign them to classes they have created. In this process, it is essential to identify the class or set of classes to be distinguished. A method is required here to mathematically determine the characteristics of the selected class. This can be most easily achieved by the researcher selecting a small group of pixels from the image itself, which serves as a dataset representing the characteristics of the specified class. If an image fragment contains multiple color tones, it is worth sampling them all, thus minimizing or avoiding the problem caused by unclassified pixels. It is worth adding more samples from the image for a given class, as this increases the accuracy of the classification. During data processing, the training dataset ranged from 50 to 500 samples for the two main classes (vegetation and water), depending on the diversity of the image. There was also a third class, referred to as the background, which was uniformly white. Since this class differed significantly from the other two, 2–3 training samples were sufficient in this case. The analysis process entails extrapolating from the training samples to the entire dataset. This type of estimation assigns all similar image fragments to the specified class, extending beyond the original training dataset.

Among the classification algorithms offered by MultiSpec, the Maximum Likelihood method was selected because of its characteristics. Classification of remotely sensed data involves determining the class of each pixel based on the spectral characteristics of different channels. Traditional methods, such as Maximum Likelihood, are based on statistical parameters such as mean and standard deviation, and include a probability model for each pixel in each class [

44]. The Maximum Likelihood Classifier (MLC) is a probabilistic classification method that assigns class labels to individual pixels based on the Maximum Likelihood Estimate of the spectral distribution of each class. The Maximum Likelihood method is one of the fundamental tools of statistical modeling [

45]. It assumes that the spectral values within a class follow a multivariate normal distribution. MLC is widely used in the treatment of mixed pixels due to its accuracy [

32]. Each pixel is assigned to the class with the highest probability. If a threshold is specified and the maximum probability is less than the specified threshold, the pixel remains unclassified. It is important to note that although the Maximum Likelihood method has several advantages, it also has limitations. In such cases where the underlying content is noisy or the model is poorly specified, alternative methods may be more appropriate [

45]. After the classification was performed, the individual classes were displayed in different colors in the image. These colors of the classes could be changed as desired, depending on what is best represented to achieve the established goals. In

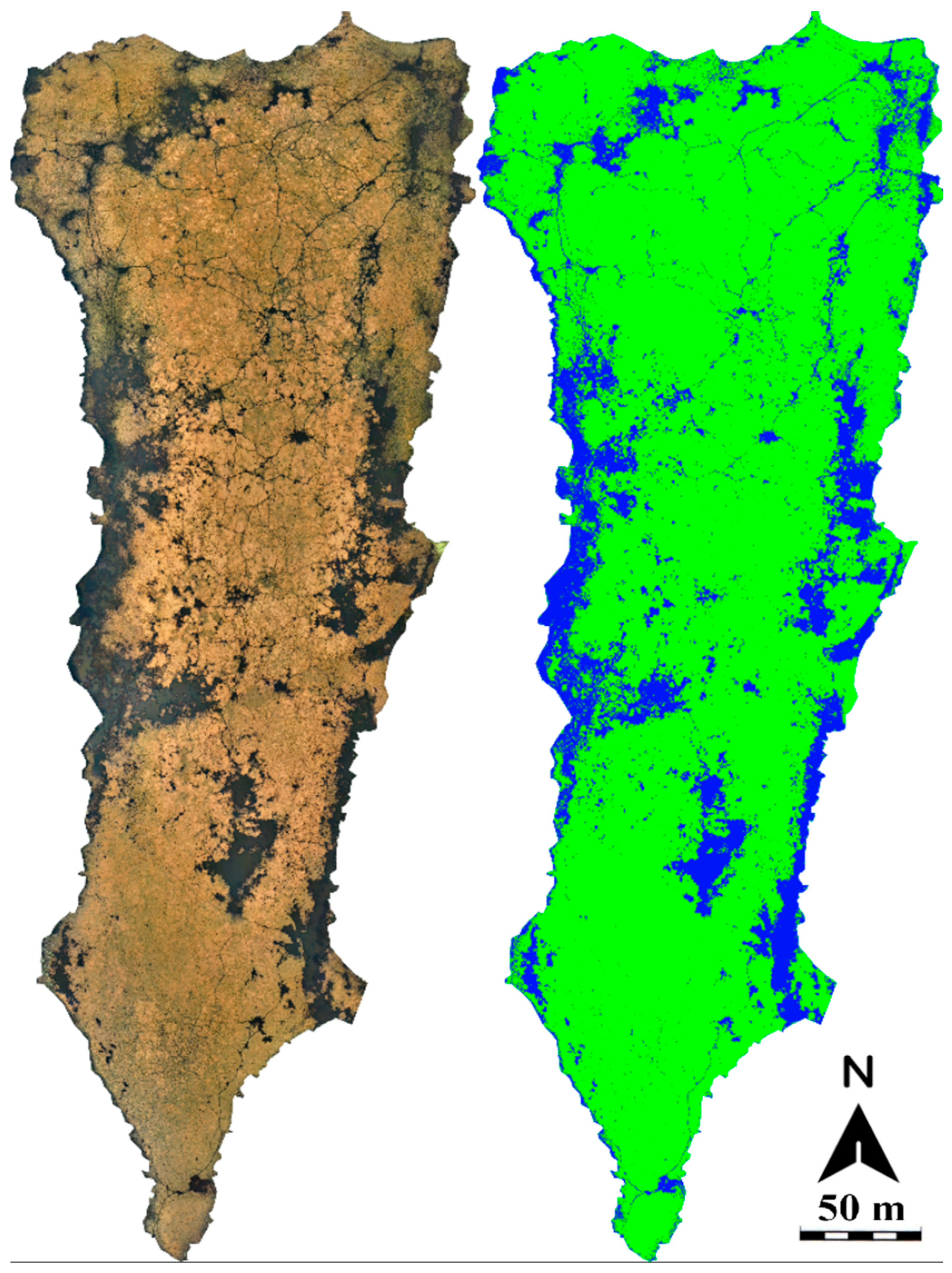

Figure 4, the open water surface is marked in blue, and the surface covered with vegetation is marked in green. The work was essentially completed using these two classes. In addition to these, a third class, the background, was also established.

In addition to the classification result, the MultiSpec software also assigns Cohen’s kappa statistic, an indicator of classification accuracy. A discrete multivariate technique of use in accuracy assessment is called kappa [

46]. Cohen’s kappa coefficient is a commonly used method for estimating interrater agreement for nominal and/or ordinal data, and was considered reliable in this experiment. Thus, agreement is adjusted for that expected by chance. Cohen’s kappa is symbolized by the lower-case Greek letter, κ. Its value can range from −1 to +1, where 0 represents the amount of agreement that can be expected from random chance, and 1 represents perfect agreement between the raters. While kappa values below 0 are possible, Cohen notes these situations are unlikely in practice. As with all correlation statistics, the kappa is a standardized value and thus is interpreted the same across multiple studies. Use of the kappa analysis assumes a multinomial sampling model. Only simple random sampling completely satisfies this assumption [

47].

Cohen suggested the kappa result be interpreted as follows. A negative kappa represents agreement worse than expected, or disagreement. Kappa values below zero are rare, but if they do occur, they indicate a serious problem. Low negative values (0 to −0.10) may generally be interpreted as no agreement. A large negative kappa represents great disagreement among raters. In the case of a positive kappa value, the higher the value, the greater the agreement. A value of 0.01–0.20 can be interpreted as none to slight, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1.00 as almost perfect agreement. However, this interpretation allows for very little agreement among raters to be described as “substantial”. For percent agreement, 61% agreement can immediately be seen as problematic. Almost 40% of the data in the dataset represent faulty data. In many areas of research, it would be a serious quality problem if 40% of the sample evaluations were incorrect. This is why many texts recommend 80% agreement as the minimum acceptable interrater agreement. Given the reduction from percent agreement that is typical in kappa results, some lowering of standards from percent agreement appears logical. However, accepting 0.40 to 0.60 as moderate may imply that the lowest value (0.40) is adequate agreement. A kappa value below 0.60 indicates inadequate agreement between raters, meaning that the results of the study are not necessarily reliable [

48].

2.5. Meteorological Data

Meteorological data used in the research were collected by a QLC-50 automatic climate station (Vaisala, Helsinki, Finland). There were two meteorological stations located near the areas being studied, one in Keszthely and another in Sármellék. Their distances from the test sites are 14 and 9 km, respectively. Since these stations provide reliable data within a 15 km radius, the values measured by the two stations were almost identical. The station collects data every 2 s and records 10 min averages. Hourly, daily, and monthly averages are calculated by averaging the 10 min records for that time interval. The experiment used the monthly average temperature (Ta), monthly minimum temperature (Tmin), monthly maximum temperature (Tmax), wind speed (u), global solar radiation (Rs), precipitation (P), and the number of rainy days. The number of days with precipitation (Pd) had to be calculated. All days with at least 0.1 mm of precipitation were considered rainy days. Meteorological station data are available free of charge on the HungaroMet website.

Statistical analysis of meteorological elements was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.1.0 (171), employing one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The comparison of meteorological elements with the classification results was conducted using Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2021 Excel software. Initially, correlation matrices were created to visualize the relationships between individual factors. Subsequently, the factors exhibiting a stronger correlation in the correlation matrix were subjected to regression analysis. The

p-values obtained by regression can be found in

Section 3.

3. Results

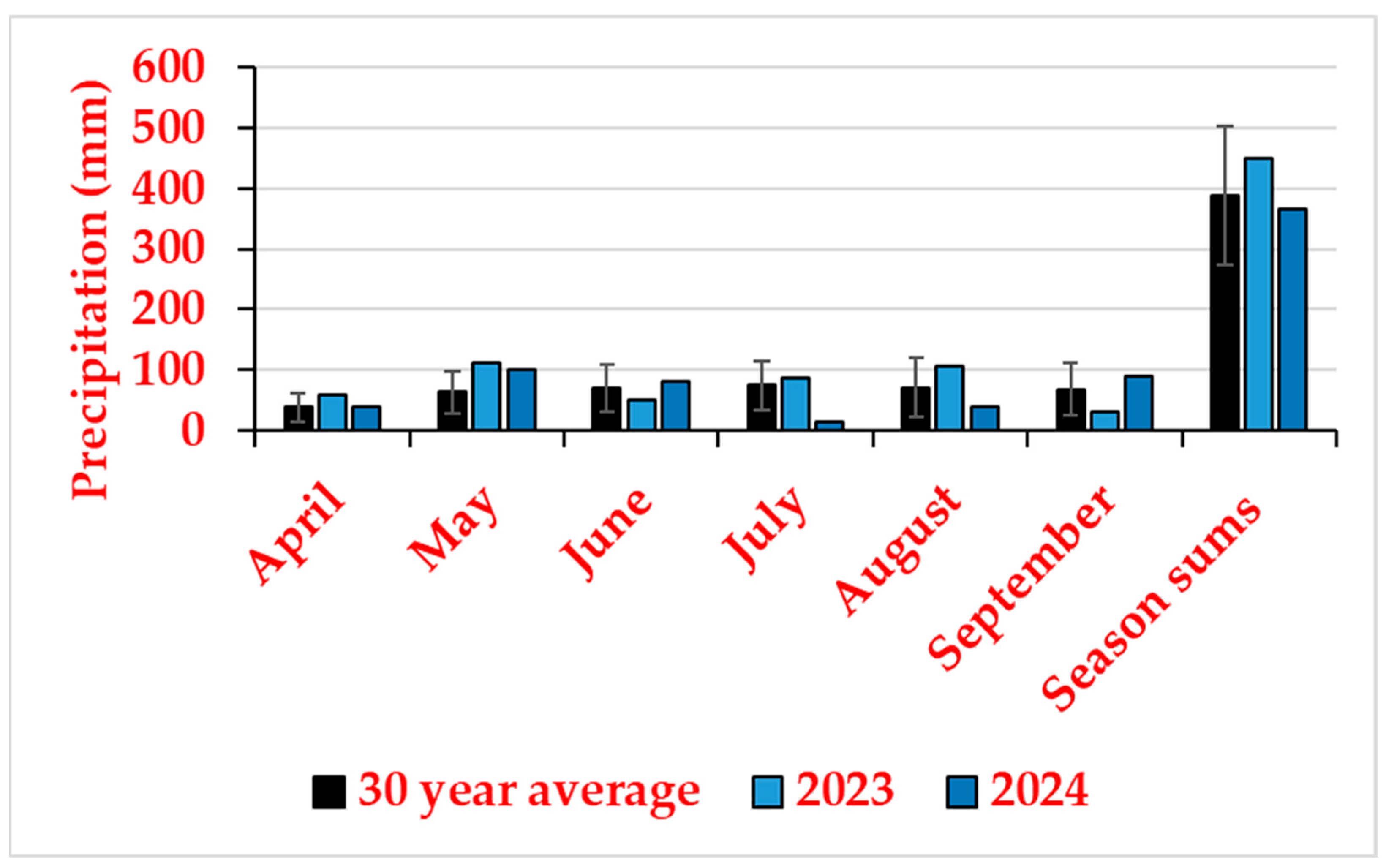

The meteorological data for the years 2023 and 2024 were compared with the long-term average (climate norm). The question was whether the data from the two years compared with the thirty-year average. The climate norm covers the period 1991–2020 for both monthly precipitation sums and average air temperatures. For this reason, the climate normals’ data represent a 30-year time interval. The growing season of 2023 experienced a considerable amount of precipitation; 449.8 mm of precipitation fell from April to September. This amount is significantly higher than the thirty-year average of 387.97 ± 113.69 mm (p < 0.001). In monthly terms, significantly more (p < 0.001) precipitation fell in the months of April (59.7 mm), May (111.1 mm), and August (106.8 mm) than the average of the previous three decades (April: 38.61 ± 23.92 mm, May: 65.08 ± 35.19 mm, August: 71.28 ± 47.8 mm). There was no significant difference between the monthly sums of July and the climate norm. In September, significantly less precipitation was experienced (p < 0.001) in 2023 (32.3 mm) compared to the long-term average (68.64 ± 44.25 mm). This was also the case in June (p = 0.006), with less monthly precipitation sum (51.7 mm) than the long-term mean (70.54 ± 38.95 mm).

The corresponding period in 2024 had drier conditions. The seasonal mean precipitation sum of 366.6 mm was not significantly different from the long-term average. Significantly more monthly rainfall sums were observed in May (101.8 mm,

p < 0.001) and September (88.5 mm,

p < 0.011) compared to the long-term means (May: 64.08 ± 35.19, September: 68.64 ± 44.25). There was no significant difference between April and June and the thirty-year average. July was noticeably (

p < 0.001) dry with 14.5 mm, and August has likewise been below average (

p = 0.001) with 38.3 mm precipitation sums (July: 74.82 ± 40.20, August: 71.28 ± 47.80) (

Figure 5).

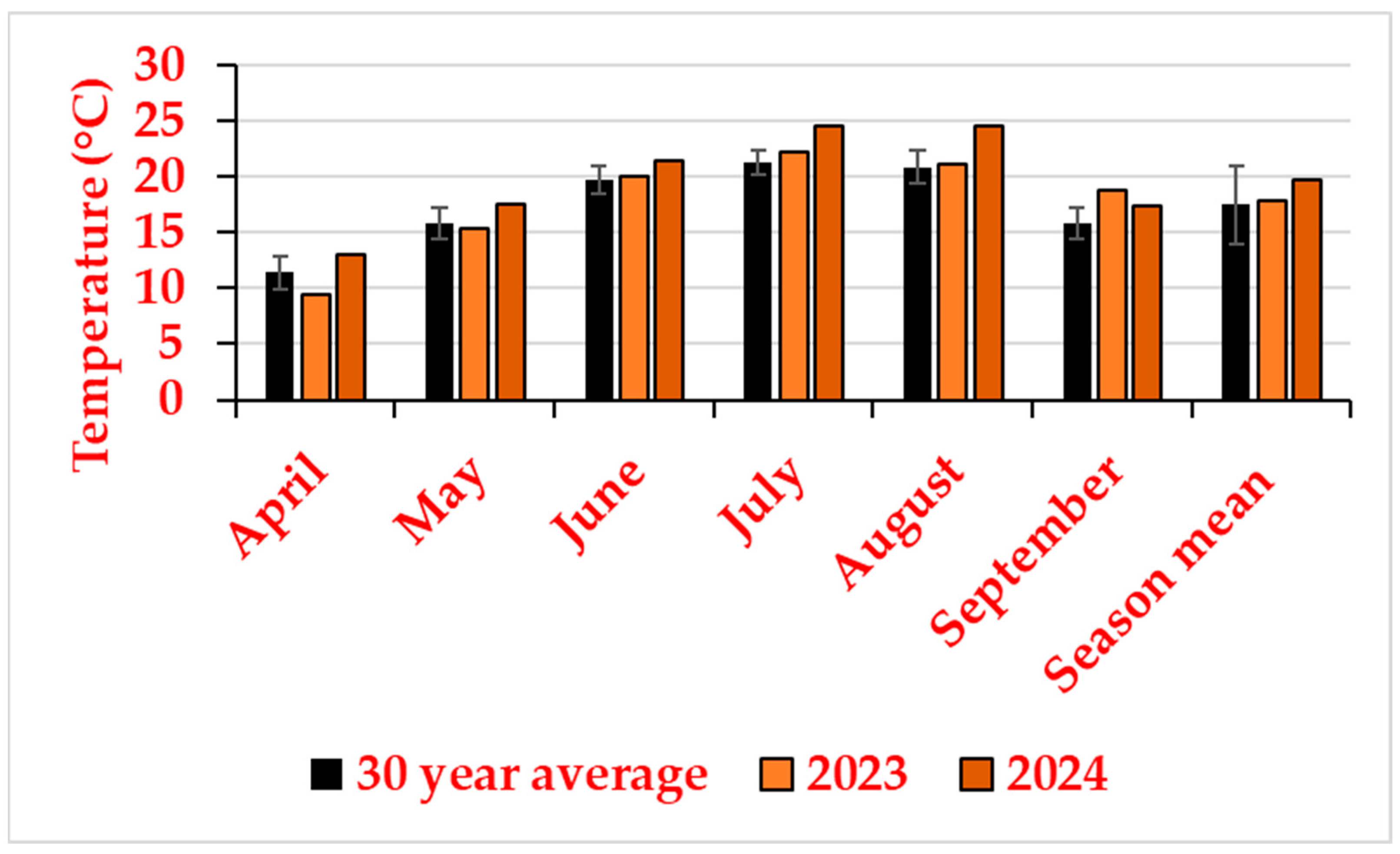

The growing season in 2023 was about half a degree warmer (17.83 °C; p = 0.009) than the long-term average (17.49 ± 3.49 °C). Except for April, when the weather was 2.0 °C cooler than the climate norm, the monthly mean air temperatures were higher in July (0.9 °C, p < 0.001) and September (2.9 °C, p < 0.001). In all remaining months, the monthly mean temperatures were in line with the long-term means.

The seasonal mean temperature of 2024 (19.75 °C) differed significantly (

p < 0.001) from the 30-year climate norm (17.49 ± 3.49 °C). The difference between the measured monthly mean temperatures (April: 13 °C, May: 17.6 °C, June: 21.5 °C, July: 24.5 °C, August: 24.5 °C, September: 17.4 °C) and the 30-year averages (April: 11.39 ± 1.61 °C, May: 15.84 ± 1.76 °C, June: 19.66 ± 1.84 °C, July: 21.32 ± 3.18 °C, August: 20.86 ± 3.64 °C, September: 15.88 ± 1.52 °C) ranged from 1.52 °C to 3.64 °C (

p < 0.001 in all months) (

Figure 6).

The information content of the images was analyzed using Shannon entropy, and a spectral fractal dimension (SFD) measurement was also conducted. Subsequently, the entropy-weighted spectral fractal structure was also investigated (

Table 2). The entropy of the channels is almost the same, but in the case of the lake, it is an order of magnitude higher. This is because the area of the lake is much larger, consists of more pixels, and has a higher cardinality. Therefore, the average information content of the lake is higher.

In the case of classifications, the goal was to achieve high kappa values. This statistical indicator demonstrates that the classification results are significant and warrant serious consideration. It was necessary to exercise caution to ensure that the number of training samples was not insufficient. The Maximum Likelihood Classification algorithm is sensitive to cardinality. The more correctly selected training samples are assigned to the class, the more accurate the classification results will be.

Considering the average seasonal coverage values, except for channel 5, surface coverage was almost higher in 2024 than in 2023. This was true for the lake as well as for most of the flow-supporting channels. Channel 5 was fundamentally special compared to the others. The majority of the water runoff occurred here, so this body of water had minimal surface coverage throughout the year (

Table 3).

Subsequently, the relationship between meteorological elements and water surface cover was examined. The main issue was the change in the cover of different types of water bodies. Since there are two meteorological stations within a 15 km radius of the studied areas, the results were compared using data from both stations. To ensure that there was sufficient data available for correlation, the results of the two years were used in the analysis. First, the correlation matrix was generated using data from the Keszthely station (

Table 4). In the correlation matrix, positive correlations are marked in red and negative correlations are marked in blue. The darker the color, the stronger the correlation. The summary of the correlation matrices shows that thermometric factors and global solar radiation have a positive effect on water surface coverage. In contrast, the number of rainy days, precipitation, and wind speed predominantly exert a negative effect. In cases where the effect was sufficiently strong, regression was performed. The resulting

p-values highlighted where this influencing effect was significant.

In the case of the lake, a significantly positive correlation was observed between water surface coverage and the 2-year average temperature, 2-year minimum temperature, and maximum temperature, as well as global radiation (

Table 5). In the case of channels 3 and 4, this correlation is most similar to that observed at the lake. Channel 4 is closed off from other water bodies almost throughout the season, which is why it behaves like a small lake. Channel 3 can only receive some water from one side, which does not result in a significant flow. Due to the length of the canal and the negligible water inflow for most of the year, the correlation was significant with the temperature values, as well as the global solar radiation.

Continuous water flow was observed in channels 5 and 6, and the runoff during the year takes place in this section. In terms of total coverage, no significant correlation was found with any meteorological variable. When the total cover was divided into elements, it was outlined that fixed Nuphar lutea populations and temporary algal cover patches were separated on the surface of the water bodies. Correlating these, it was revealed that temperature data and global radiation have a significantly positive effect on Nuphar lutea cover on both channels 5 and 6. This cannot be said in the case of the algal population, which is probably due to the continuous water flow.

Channels 1 and 2 are connected for most of the year. The road separating them is underwater except during dry periods. Water flow is observable, but not very strong, and is only characteristic of one side. Probably because of this mixed nature, the results were between the previous two extremes. The majority of the water income comes from channel 1. There were only algae in this section. In the case of algae cover, no significant correlation was found with any meteorological element. The inflow speed decreases continuously as it approaches the road. There is no significance in the second channel. The water is much calmer in this area. The correlation was significant with two temperature components and also with global solar radiation.

Precipitation and wind speed had a negative effect on cover, but this could not be statistically significantly proven. This also applied to the number of days with precipitation. There was one exception that had a substantially adverse effect on the cover in comparison to the lake data (r2 = 0.358, p = 0.031).

Owing to the close proximity of the Sármellék meteorological station (

Table 6), the meteorological data collected there were nearly identical to those recorded in Keszthely.

An analysis of the lake data (

Table 7) revealed a significant positive correlation between water surface cover and the two-year average temperature, two-year minimum temperature, two-year maximum temperature, and global radiation.

The significance levels of channels 3 and 4 also showed minimal changes compared to the Kesztely results. This did not affect the final result; the relationship remained significant in all cases.

No significant correlations were observed in channels 5 and 6 concerning water surface cover, based on the Sármellék meteorological data either.

The situation was identical for channel 1. The numbers differed slightly, but the final outcome remained the same. In the case of channel 2, the correlation was significant with the same two temperature components and with global solar radiation.

In this case, precipitation, the number of rainy days, and wind speed also negatively affected the cover, but this could not be proven statistically significant. In only one case was a significantly negative effect demonstrated, between lake surface cover and the number of rainy days (r2 = 0.433, p = 0.014).

4. Discussion

The research highlights that rising temperatures have a positive effect on the growth of aquatic vegetation on the surface cover of water bodies. This is consistent with the results found in the literature. In the past four decades, more than 20,000 freshwater algal blooms have been observed worldwide, covering approximately 57% of the total lake surface area [

49]. The results prove that the ultra-high-resolution images provided by drones can be used excellently for monitoring these processes. This approach is particularly effective for smaller areas; indeed, certain regions, such as those examined in this research, cannot be analyzed using satellite imagery. In contrast, satellite imagery is utilized to survey extensive areas. Several studies have used satellite remote sensing data from platforms such as MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, Santa Barbara Remote Sensing (SBRS), Santa Barbara, California, United States of America), SeaWiFS (Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor, NASA (data processing) & Orbital Sciences Corporation (instrument development/launch), Greenbelt, Maryland, United States of America), MERIS (Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer, Alcatel Space Industries, Cannes-Mandelieu, France), and GOCI (Geostationary Ocean Color Imager, Korea Aerospace Research Institute, Daejeon, Republic of Korea (South Korea)) to investigate algal blooms [

50,

51,

52]. We used daily MODIS satellite data from 2003 to 2022 to examine algal bloom trends in 1956 large freshwater lakes worldwide. Of these lakes, 620 experienced algal blooms in more than half of the years, and 504 lakes experienced increased bloom rates. Similar to our results, the global average bloom rate has increased by 1.8% per year over the past twenty years, showing a remarkable correlation with air temperature (r

2 = 0.43,

p < 0.05). In addition, a strong correlation between air temperature and bloom frequency was observed in 44.8% of the lakes affected by blooms. This finding is further corroborated by this study, which also identified a significant correlation (

p < 0.01) between the surface cover of the lake and the air temperature. Algae also showed significant growth in the studied area, and their presence shows an increasing trend in warmer years. In 2024, some of the water bodies examined experienced nearly 30% higher average surface cover compared to a cooler year. This is the case in the literature, and even in both freshwater and marine environments. Dai et al. [

53] mapped daily coastal algal blooms from 2003 to 2020 using global satellite imagery with a spatial resolution of 1 km. Algal blooms were detected in 126 of the 153 coastal countries studied. Globally, the spatial extent (+13.2%) and frequency (+59.2%) of blooms increased significantly during the period studied. Wang et al. [

54] analyzed the spatial and temporal patterns of algal blooms in 171 Chinese lakes using an automated algorithm that detects blooms in medium-resolution imaging spectroradiometer images. 60.2% of the lakes were affected by algal blooms, and 95 lakes showed a gradually increasing trend. The increasing trends were closely related to the recent increase in air temperature, as in this study. In 2024, average lake cover increased from 42.72% to 64.40%, in parallel with a 1.92 °C increase in seasonal mean Ta. This trend is similarly evident in the case of channels, where the coverage value increased in five out of six instances in 2024. This value ranged between 1.75% and 29.25%. This pattern can be considered uncertain in water bodies with water flow. In our case, in one instance, the surface coverage decreased from 2.38% to 1.78%, despite higher temperature and radiation values.

The literature also shows examples of wetlands surveyed with a UAV linked to sensor data. Those examples match the wetlands, the UAV, and the sensor data in this study. Garcia et al. [

55] used data loggers and UAV photogrammetry to examine a coastal wetland. The study examined how the temporary coastal wetland works and how it interacts with the aquifer and the tidal system. Similar to our research, UAV photogrammetry mapped the wetland surface and captured the details in high resolution. Automated water level sensors recorded water stage every ten minutes, giving high-frequency data that let the researchers separate contributions from precipitation, evaporation, and groundwater fluxes. Jeziorska’s study [

56] gives an overview of the hardware, software, control systems, and scientific uses. Jeziorska’s study also covers data acquisition and post-processing steps for aerial vehicles used in wetland monitoring and hydrological modeling. He worked on a wetland study that combined UAV imagery with satellite data, geophysical data, and climatological analysis. He used the UAV data to get a more detailed seasonal analysis than the satellite data. The research revealed the complexity of wetland hydrology and showed a difference of 13 percent between the satellite data and the UAV data, which shows that using UAVs is important for monitoring and describing ecosystems, which was also crucial, in our case [

57]. Additional studies have also proven that UAVs are better suited for surveying smaller areas. El-Jamaoui et al. compared UAV and Sentinel-2 satellite imagery for estimating soil organic carbon content. They revealed that UAV data offered significantly superior predictive accuracy and spatial detail compared to Sentinel-2 satellite data [

58].

In those bodies of water where there was water flow, the algal cover was also more moderate. In cooler and warmer periods, there was not as much presence as in the case of still waters. The importance of water flow has already been drawn to the attention of others. In aquatic ecosystems, continuous water flow provides unique conditions that influence phytoplankton growth. For example, a decrease in water flow and flow velocity is also known to lead to eutrophication in freshwater bodies [

59]. In Australia, water flow has been used to suppress cyanobacterial blooms [

60], which is consistent with our results. Altering hydrology and increasing vertical mixing may be a promising way to prevent surface blooms of floating cyanobacteria [

61].

5. Conclusions

The research demonstrated that ultra-high-resolution aerial imagery is suitable for accurately determining the surface cover of smaller water bodies. These data could be meaningfully compared with the meteorological data of the studied area. This made it possible to determine which meteorological elements have the strongest impact on the surface cover of water bodies. Regarding the study area, the average temperature values of 2024 exceeded the values of 2023 in almost every month of the vegetation period. The global radiation values developed similarly to the average temperature. Both meteorological elements have a positive effect on the development of the surface cover of water bodies. The amount of precipitation and the number of rainy days, which would reduce the surface covering the water body, were less in 2024 than in 2023. Due to this, we experienced higher cover values in 2024 for the lake in the study area and for all examined channels. Although precipitation had a negative effect on cover, this could not be proven statistically significant. In the case of the lake, the relationship between total surface cover, temperature, and global radiation among the meteorological elements shows a significant value. This is consistent with the values found in the literature, as the lack of water flow favors the proliferation of phytoplankton in addition to aquatic plants. Temperature data and global radiation also exhibited a significant correlation for channels that were more isolated or lacked flow. Lower surface coverage values were observed in channels with continuous water flow. In the case of a channel with continuous water flow, the average surface coverage was one-thirtieth that of the most isolated channel. There was no significant correlation with these meteorological elements either. An analysis of the total coverage divided into parts indicated that the correlation is significant in the case of fixed plant stands (for example, Nuphar lutea). In these cases, the problem was algae cover, which, according to the literature, is negatively affected by water flow and flow velocity. The research highlights that water surface cover is affected not only by meteorological elements but also by flow conditions. Based on the results from the examined periods, we therefore concluded that higher vegetation water surface coverage is more characteristic of years with elevated temperatures and reduced precipitation. Accordingly, in relatively isolated systems where flow is weak or nonexistent, such as a lake, water surface coverage exhibits a significant positive correlation with temperature variables and global solar radiation. From this, it can be concluded that thermal conditions and energy input are the primary factors influencing vegetation development, particularly in water bodies characterized by prolonged water residence time and minimal physical disturbance. Future plans include decomposing the water surface cover into its constituent elements. This would make it possible to determine which vegetation dominates the lake and the individual channels in each year. The dataset will be expanded to include data from 2025 and, likely, 2026. We aim to analyze data spanning as many years as possible to enhance the reliability of the results. The plans also encompass detailed mapping of the flow conditions in the channels, supported by numerical data.