1. Introduction

Accurate and detailed documentation of interior spaces represents an important component of geodetic documentation for buildings, architectural heritage, and technical facilities. Over the past decade, modern methods of mass 3D data acquisition, such as photogrammetric scanning and terrestrial laser scanning, have been increasingly applied in this field. These methods enable highly efficient creation of precise point clouds or 3D models of objects with high resolution and geometric accuracy. Each of these methods has its own advantages and limitations, which predetermine their suitability for specific applications [

1]. In interior environments, terrestrial laser scanning clearly dominates, whether in the form of static terrestrial laser scanners or mobile terrestrial laser scanning systems. The output of terrestrial laser scanning is a point cloud usually with correct orientation and scale. Furthermore, terrestrial laser scanners do not require surface texture variation or homogeneous lighting of the object. On the other hand, a major drawback of these scanners is their significantly higher cost compared to cameras. Photogrammetric scanning is generally less effective in interior spaces, mainly due to insufficient lighting, the need to introduce scale, and often also the lack of suitable textures for traditional (frame) images. Moreover, in many cases the presence of hard-to-access or confined areas requires the use of specialized scanning approaches [

2]. A possible solution is the use of 360° cameras, which capture panoramic images with an extended field of view and can often record an entire interior in a single image, thus providing at least partial texture variation [

3]. In addition, most modern panoramic (360°) cameras allow image acquisition with extended dynamic range (10-bit, 12-bit, etc.) or in HDR (High Dynamic Range) mode, enabling the production of sufficiently illuminated images even under poor lighting conditions.

Panoramic images can be classified according to their projection geometry into cylindrical, spherical and cubic types. Each type has distinct characteristics and suitability for specific photogrammetric applications:

cylindrical panorama uses a cylindrical projection, in which the scene is projected onto the surface of a usually vertical cylinder, ideally with its center at the camera’s projection center. This type of panorama is created when images captured by a single camera rotating around a vertical axis or multiple images from different positions (e.g., multi-camera systems) are laterally stitched together to cover a 360° horizontal field of view. The vertical field of view is limited by the camera’s angle of view. Cylindrical panoramas are technically less demanding to process, as they preserve vertical lines and do not require full spatial coverage;

spherical panorama uses a spherical projection, where the entire scene is projected onto the surface of a sphere, ideally centered at the projection center. It covers the full spatial extent of 360° × 180°. Spherical panoramas are generated either using multi-camera systems or 360° cameras equipped with two opposing fish-eye lenses that capture the entire field of view (

Figure 1). The complete scene information enables realistic visualization and a high degree of automation in 3D reconstruction; however, processing requires advanced algorithms for alignment, stitching, and precise calibration of lenses with significant radial distortion;

cubic panorama uses a cubic projection, in which the spherical scene is mapped onto the six faces of an imaginary cube surrounding the projection center. Each face represents a 90° × 90° rectilinear image corresponding to one of the principal directions (front, back, left, right, top, and bottom). This projection is particularly suitable for photogrammetric and visualization applications, as it maintains linear perspective and minimizes local distortions compared to equirectangular projections. In addition, cubic panoramas are employed for the transformation of other panoramic projection types into conventional frame projections.

Panoramic images play a significant role in spatial mapping and 3D documentation. In geodetic practice, they have become an integral component of terrestrial laser scanning and mobile mapping systems, where they serve as a complementary data source to the acquired 3D points. Panoramic images provide color information, which is essential for texturing and coloring point clouds. At the same time, they enable visual orientation within the space captured by the scanner or photogrammetric camera.

Mostly for outdoor activities, the development of compact 360° (spherical) cameras in recent years have opened new possibilities for low-cost and rapid spatial documentation [

4]. These devices enable the acquisition of complete panoramic images with a 360° × 180° field of view from various camera positions, which can subsequently be processed using panoramic photogrammetry methods to obtain 3D data. Spherical cameras offer high image resolution, support for RAW image capture, and modes with an extended dynamic range (HDR). Despite these advantages, the metric properties of reconstruction derived from spherical cameras are still being investigated. Several studies have already analyzed the accuracy of panoramic photogrammetry across different scene types and camera systems [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Their findings show that accuracy is strongly influenced by the image configuration, the quality of calibration, as well as the surface characteristics present in the scene. Interior environments with flat, low-contrast textures and with weak or uneven illumination often result in a significant reduction in the reliability of corresponding points and in local deformations of the model [

11].

The aim of this work is to experimentally evaluate the influence of the number of panoramic images and the camera network on the metric accuracy of a 3D interior reconstruction obtained through panoramic photogrammetry using a Ricoh Theta Z1 camera. The experiment focuses on specific conditions that are particularly challenging for this type of documentation—an interior with flat textures and poor lighting conditions. Precise measurements from static terrestrial laser scanning were used as reference data. The analysis involves comparing six processing variants of panoramic photogrammetry, each using a different number of panoramic images. A dense point cloud was generated for each variant and subsequently compared with the reference point cloud obtained from terrestrial laser scanning. The objective of this study is to evaluate how the reduction in the number of panoramic images influences the geometric accuracy of interior reconstruction and the completeness of the resulting dense point cloud, and to determine a practical threshold between acquisition efficiency and the required metric quality.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology of this work is based on the use of panoramic images as the primary visual source for generating a photogrammetric dense point cloud to document the interior spaces. In the processing of panoramic imagery, a procedure known as panoramic photogrammetry is applied, which enables the reconstruction of the spatial geometry of an object using spherical, cylindrical or cubic image projections.

2.1. Panoramic Photogrammetry

Panoramic photogrammetry uses images with a wide or full field of view to reconstruct 3D space. In this work, the focus is placed on spherical panoramic images, as the Ricoh Theta Z1 camera creates. Spherical camera Ricoh Theta Z1 is equipped with two opposing fish-eye lenses that allow capturing the entire scene within 360° × 180°. The output consists of two hemispherical images that are stitched into a single spherical panorama, where each image pixel represents a defining ray originating from the camera’s projection center. The photogrammetric processing of panoramic images applied in this work is based on the principles of Structure from Motion (SfM) and bundle block adjustment. In classical photogrammetric scanning, the fundamental principle is collinearity—meaning that the object point, the projection center, and the corresponding image point lie on a single straight line. This principle is mathematically expressed by the collinearity equations [

12]:

where

,

are the image coordinates,

,

are the image coordinates of the principal point,

is the focal length,

,

,

are the object (reference) coordinates,

,

,

are the object coordinates of the projection center and

–

are the elements of the orthogonal rotation matrix. The purpose of the collinearity equations is to define the relationship between a point in the image plane and its corresponding point in object space. This relationship can be expressed in a simplified mathematical form as follows [

12]:

where

,

,

,

and

is scale factor.

In spherical projection, measurements on a panoramic image are not expressed in Cartesian image coordinates, but rather in angular coordinates, where

is the horizontal angle (azimuth) and

is the vertical angle (elevation):

The measured spherical coordinates must then be transformed (unwrapped) into Cartesian image coordinates [

13]. Based on

Figure 2, the image coordinates of a point can be derived from its spherical coordinates as follows:

Subsequently, using Equations (1)–(4), the final collinearity equations for spherical panoramic images can be formulated [

13]:

These modified collinearity equations, expressed for spherical images, are then used in the bundle block adjustment. If enough observations are available, the collinearity equations may be extended by distortion parameters specific to spherical imagery. In our case, the interior orientation parameters are estimated separately for both sensors equipped with fish-eye lenses in the spherical camera.

2.2. Calibration of Fish-Eye Lenses

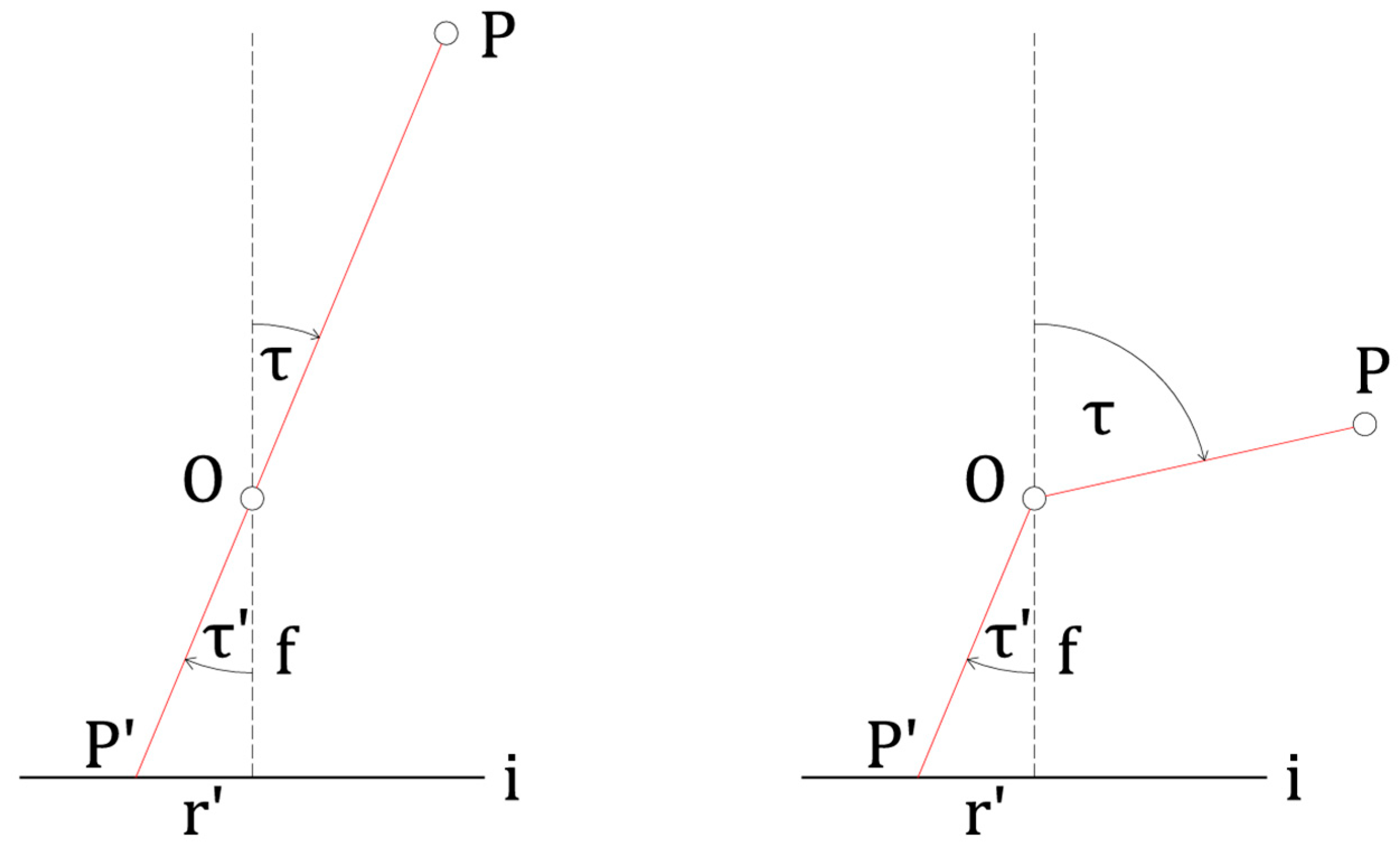

The calibration of fish-eye lenses requires a specific approach due to their geometry and extensive field of view [

14]. These characteristics significantly affect the geometric properties of fish-eye images, particularly the ability to depict straight lines from the object space as straight lines in the image [

15,

16]. A suitable solution is to replace the central projection, where the incident and exit angles

t and

t′ are ideally identical, with an alternative projection model in which the exit angle

t′ is significantly smaller than the incident angle

t. This results in a specific fish-eye projection that enables capturing a hemispherical field of view (

Figure 3). Instead of the central projection, three commonly used projection models are applied for fish-eye lenses: stereographic, equidistant, and orthographic (

Table 1) [

12].

When modelling the distortion of a fish-eye lens, it is necessary to apply the correct projection model prior to estimating the lens distortion parameters [

12]. Radial distortion reaches significantly higher values towards the image edges compared to a conventional frame image; therefore, extended Brown’s non-linear lens distortion terms are used. Calibration is typically carried out through self-calibration—an indirect estimation of the interior orientation parameters within a bundle block adjustment. These interior orientation parameters include: the focal length

, the principal point coordinates

, the lens distortion coefficients—radial (

), decentering (

) and the affinity/skew parameters of the sensor (

) [

18,

19]:

where

is the radial distance of a given point with image coordinates

,

;

,

,

are the radial distortion parameters,

,

are the decentering distortion parameters and

are the affinity and skew parameters of the sensor. This approach enables accurate determination of the interior orientation parameters and correction of the non-linear distortion of the fish-eye lens. When using a spherical camera equipped with two fish-eye lenses, the interior orientation parameters must be estimated separately for each sensor. This requirement must be considered in the processing of spherical panoramic images, including in our case applying the Ricoh Theta Z1 spherical camera.

3. Case Study: House of Samuel Mikovíni

The historic house in the center of Banská Štiavnica is known as the House of Samuel Mikovíni. This townhouse has a medieval core that was gradually modified in Renaissance, Baroque, and Classicist styles. In the first half of the 18th century, it was owned by the prominent polymath, surveyor, cartographer, educator, and engineer Samuel Mikovíni (1686–1750), who not only lived there but is also believed to have taught in the building at one of the first technical schools in the Kingdom of Hungary. The building is currently undergoing restoration and a planned comprehensive renewal, with the aim of revitalizing not only its architectural elements but also transforming it into a cultural and educational space that reflects Mikovíni’s innovative and scientific legacy.

For this study, the building was selected specifically due to the diversity of its interior spaces. The object contains numerous transitions, inclined and curved surfaces, walls of varying thickness, flat surfaces with poor texture, as well as alternating areas of favorable and unfavorable lighting conditions. These characteristics made the site suitable for testing the accuracy of panoramic photogrammetry (

Figure 4).

3.1. Scanning Using Panoramic Photogrammetry

As mentioned previously, the reconstruction of the interior spaces of the house of Samuel Mikovíni was carried out using the Ricoh Theta Z1 spherical camera (

Figure 5) [

20]:

sensor type: dual 1.0-inch (1.0″) back-illuminated CMOS image sensor with a pixel size of approximately 2.41 μm,

maximum image resolution: approximately 23 megapixels, i.e., JPEG 6720 × 3360 pixels,

image formats: supports RAW (DNG) and JPEG output for still images,

lens: dual 180° (two opposing lenses) with a 14-element, 10-group construction,

aperture: stepwise adjustable values of F2.1, F3.5 a F5.6,

video: supports 4K video (e.g., 3840 × 1920 at 30 FPS) and 360° live streaming,

internal storage capacity: 51 GB,

sensor sensitivity support: ISO up to 6400,

HDR capture mode support,

price: 1400 €.

Image acquisition was carried out in the interior spaces of the House of Samuel Mikovíni using a tripod at a minimum of two different height levels. In areas with higher ceilings, images were captured from more than two height levels (e.g., the second floor, staircases, etc.). Due to variable lighting conditions, the HDR capture mode was employed. A total of 252 spherical panoramic images were acquired, fully utilizing the camera’s battery capacity. In each room, several images were taken depending on the shape and size of the space, with additional images captured in the transitions between rooms. The average GSD in the images reached approximately 1.3 mm. The scale of the model was determined based on five significant lengths measured with a measuring tape in different directions and locations throughout the House of Samuel Mikovíni (

Figure 6). Length measurements were selected instead of using ground control points, as establishing a ground control points network in interior spaces is significantly more demanding in terms of surveying effort, time and overall cost. The measured lengths were selected at locations where they could be unambiguously measured with a tape and clearly identified in the images. In this case, these were the dimensions of door frames and window openings. The aim of this work is to achieve the final reconstruction using panoramic photogrammetry under the most low-cost conditions possible, which in this case is represented by measuring a set of significant distances using a measuring tape.

The processing of spherical panoramas was performed using Agisoft Metashape 2.1.0 software [

21]. The images were imported, and the camera type was set to spherical in the calibration tab. The images were then aligned (setting parameters—Accuracy: High, Key Points: 80,000, Tie Points: 20,000). After image alignment, the sparse point cloud was filtered to remove outliers, and depth maps were generated from the spherical panoramas (Quality: Ultra High). Dense point clouds were subsequently generated directly from the depth maps at the same quality level. The dense point clouds were then filtered to remove points outside the area of interest (artifacts, reconstructions through open windows and areas outside the House of Samuel Mikovíni). Finally, significant lengths were measured on the images. Three lengths (in three directions of the local coordinate system—02, 04 and 05) were used as control lengths, to apply the correct scale to the photogrammetric reconstruction, while the remaining two lengths (01 and 03) served as check measurements to verify the accuracy of the transformation into the metric system. Based on the position of the lengths, their manual measurement on the images, and the average GSD of the images, the accuracy of determining the lengths using the measuring tape was set to 0.005 m (

Table 2). The resulting dense point cloud was resampled to a resolution of 0.005 m. An example of the resulting point cloud from panoramic photogrammetry using all images is shown in

Figure 5.

3.2. Reference Data from Terrestrial Laser Scanning

Reference data were acquired using terrestrial laser scanning with the high-speed 3D laser scanner Leica RTC360 (Leica Geosystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) (

Figure 7) [

22]:

point cloud resolution—offers three levels: 3/6/12 mm at 10 m,

range measurement accuracy: 1.0 mm + 10 ppm,

angular measurement accuracy: 18″,

field of view: 360° horizontal, 300° vertical,

measuring range: 0.5 m–130 m,

scanning speed: up to 2,000,000 points per second,

three-dimensional point position accuracy: 1.9 mm at 10 m, 2.9 mm at 20 m, and 5.3 mm at 40 m,

range noise: 0.4 mm at 10 m, 0.5 mm at 20 m,

spherical imaging system for colorizing the point cloud,

Visual Inertial System (VIS) for real-time scan registration,

price: 70,000 €.

Terrestrial laser scanning of the interior spaces of the house of Samuel Mikovíni was carried out using a fixed scanning tripod. Several scanner positions were used in each room to ensure sufficient detail and density of the resulting point cloud. Additional scanner positions were placed in the transitional areas between rooms, ensuring robust scan registration. The total number of scan positions was 43.

Processing of the terrestrial laser scanning data was performed in the Leica Cyclone REGISTER 360+ Version 2023.0 software [

23]. Individual scans were registered automatically based on identical planes. The accuracy of the final registration is characterized by the RMSE of the residuals between the individual scans, reaching 0.9 mm. The resulting point cloud was resampled to a resolution of 0.005 m. A preview of the reference point cloud from terrestrial laser scanning is shown in

Figure 7.

3.3. Difference Point Cloud

After obtaining the dense point cloud from panoramic photogrammetry and the reference point cloud from terrestrial laser scanning, it is necessary to compare these point clouds to analyze the accuracy achieved by panoramic photogrammetry. This comparison is performed using a so-called difference point cloud, where the deviation (mutual distances) between the reference point cloud and the panoramic photogrammetry dense point cloud is calculated. This calculation was carried out in Cloud Compare Version 2.13.beta software [

24]. The first step is the registration of both point clouds. Although both clouds are scaled metrically, they exist in different local coordinate systems. For an exact comparison, the point clouds must be registered relative to each other. Registration is performed in two steps. First, a rough alignment using the function “Align two clouds by picking (at least 4) equivalent point pairs” (

Figure 8), followed by a precise registration using the ICP (Iterative Closest Point) transformation with the function “Finely register already (roughly) aligned entities (clouds or meshes)” (

Table 3). The reference and the aligned point clouds were selected in the ICP dialog, and corresponding point pairs were automatically determined based on the closest-point criterion. Uniform random sampling of 100,000 points was applied to reduce computational complexity, while all other ICP parameters were kept at their default settings. A rigid transformation model consisting of translation and rotation was used, without additional weighting or the use of surface normals. The ICP process iteratively minimized the RMS distance between corresponding points until convergence was achieved. The quality of the registration was subsequently assessed using the resulting RMSE of the ICP transformation (

Table 3). Once the point clouds are registered, the difference model can be directly computed using the “Compute cloud/cloud distance” function. Cloud-to-cloud distances were computed using the default point-to-point distance computation, where for each point of the compared cloud the distance to the nearest point in the reference cloud is evaluated. All remaining parameters were kept at their default values. This approach allows a direct assessment of geometric deviations between the registered point clouds. The resulting difference model is then prepared for visualization.

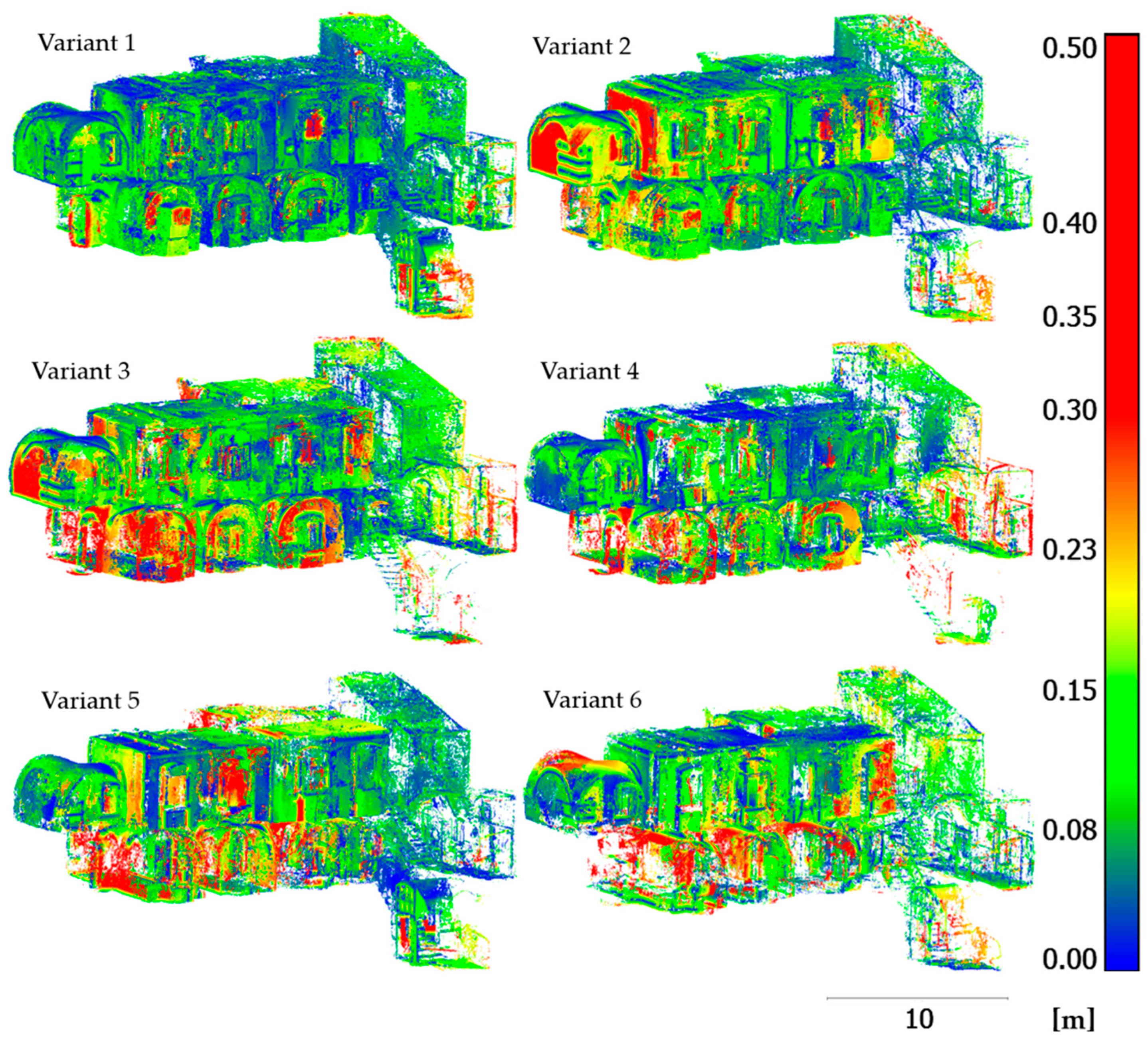

3.4. Impact of the Camera Network on Reconstruction Results

The aim of the practical part of this study is to determine the influence of the number of images on the resulting accuracy of the panoramic point cloud of the interior spaces of the House of Samuel Mikovíni. Accuracy is evaluated by computing the difference point cloud (

Section 3.3). The reference point cloud is taken from terrestrial laser scanning (

Section 3.2), and the processing of point clouds using panoramic photogrammetry is described in

Section 3.1. Six separate photogrammetric processing runs are performed using panoramic images, with each run employing a different number of images and variants:

all available images are used to generate the point cloud via panoramic photogrammetry (number of images: 252; number of points: 50.0 million);

approximately every second image from Variant 1 is used (number of images: 168; number of points: 38.0 million);

only panoramic images from the lower height level throughout the building are used (number of images: 104; number of points: 33.7 million);

approximately every second image from Variant 3 is used (number of images: 58; number of points: 22.2 million);

only panoramic images from the upper height level throughout the building are used (number of images: 114; number of points: 23.7 million);

approximately every second image from Variant 5 is used (number of images: 65; number of points: 18.2 million).

For each variant a separate difference point cloud is generated, and the resulting accuracies are subsequently compared. The varying number of spherical images is illustrated in

Figure 9.

Variant 1 represents the full utilization of the battery capacity of the Ricoh Theta Z1 camera, with images captured at two to three different height levels, as previously mentioned. The positional arrangement of the camera stations was determined by the shape of each room. The following figure shows an example of how the camera stations were selected for Variant 1 across different rooms (

Figure 10). In addition, for a better understanding of the camera network density, we provide a table showing the calculation of the average area of the House of Samuel Mikovíni corresponding to each spherical image for the individual variants (

Table 4).

4. Results

The difference point clouds were visualized for each variant in an axonometric view

Figure 11. Difference values exceeding 0.20 m were visualized in red, while values greater than 0.50 m were removed from the analysis. The removed values represented outliers in the distance comparison between the reference point cloud and the photogrammetric reconstruction. Such outliers typically arise from noise, insufficient reconstruction of low-texture or poorly illuminated surfaces. In addition, larger discrepancies were caused by changes in the interior between the time of terrestrial laser scanning and panoramic photogrammetry, such as the presence or absence of small objects, shifts in furniture, or variations in occluded areas. Across all variants, the proportion of these points remained around 2% of the entire point cloud, except for Variant 6, where it reached 3.5%. This, combined with the number of spherical images used for detailed interior reconstruction, results in a significant reduction in points as the number of images decreases. In Variants 3 to 6, positional loss of some walls occurs, particularly in areas with flat textures. In these cases, adding more images in Variants 1 and 2 improved the reconstruction. Differences between Variants 1 and 2 also indicate that a larger number of images and thorough coverage can increase the accuracy of the resulting interior reconstruction. In Variants 2 and 3, some walls show differences of up to 0.20 m compared to the reference point cloud, whereas Variant 1 significantly reduces these differences to 0.10 m, and in some areas even to 0.05 m. In Variant 1, only unstable parts of the reconstruction, such as doors, furniture, and windows are highlighted in red. Another positive outcome is the robust orientation of the spherical images. In all variants, including Variants 4 and 6, which contain the lowest number of spherical images, image alignment succeeded on the first attempt, with no misaligned or unaligned images. This advantage is attributed to the full field of view of the images and the high-quality exposure achieved using HDR capture mode.

Figure 12 presents a comparison of all variants for a floor-plan section of the point cloud at window level on the second floor. Again, all difference values exceeding 0.20 m were visualized in red and all values greater than 0.50 m were removed from the analysis. The sections for all variants contain points with differences up to 0.15 m, except for a few areas. Variant 1, which includes the greatest number of spherical images, shows most walls in blue, indicating an accuracy of up to 0.05 m—even in areas with flat textures and poor lighting conditions.

The histograms of the differences are shown in

Figure 13. These illustrate how the distribution of the differences changes across the individual variants of the difference point clouds. With respect to this distribution, we can observe that as the number of spherical images used decreases, the frequency of points with small differences decreases, while the frequency of points with larger differences increases—indicating a decline in the geometric accuracy of the object reconstruction. This observation is further confirmed in

Table 5, which presents the basic statistics of the difference models, such as the mean value and the standard deviation.

The mean values range from 0.08 m to 0.14 m across the variants, while the standard deviation remains relatively high (0.11–0.14 m). This increased variability reflects the inherently lower depth accuracy of panoramic photogrammetry in indoor environments, particularly in areas affected by weak texture, unfavorable lighting, and partial occlusions. Moreover, part of the variability originates from real geometric and radiometric differences between epochs of acquisition, as the terrestrial laser scanning and spherical images were captured at different times. As the number of spherical images decreases, these effects become more pronounced, leading to a broader spread of differences and thus reduced geometric stability of the reconstruction. Overall, the statistical results clearly demonstrate that denser image networks (Variants 1 and 2) provide higher metric reliability compared to sparser configurations. A notable exception is Variant 4, where both the mean difference and the standard deviation reached values comparable to those of Variant 2. However, in this case we assume that these favorable results are primarily a consequence of filtering out a substantial portion of points with large discrepancies. Moreover, the resulting photogrammetric reconstruction contains significantly fewer points than in Variants 1 and 2.

The final visualization presents a detailed view of one of the rooms in the house of Samuel Mikovíni (

Figure 14). Here as well, differences exceeding 0.20 m were visualized in red, while differences greater than 0.50 m were removed from the analysis. This visualization confirms the previous observations, namely that a higher number of images ensures a more accurate geometric reconstruction and a greater number of projections, resulting in increased detail of the final dense point cloud obtained from panoramic photogrammetry.

5. Discussion

The experiments demonstrated that panoramic photogrammetry could produce high-quality documentation even in conditions that are generally challenging for photogrammetry, using a low-cost spherical camera. Such documentation typically includes the creation of floor plans or vertical sections as well as simple area calculations and length measurements on the object. The accuracy of this type of documentation can reach values between 0.05 m and 0.15 m, depending on the number of spherical images used, as well as on the camera employed, the surface texture of the object, and the lighting conditions. Compared to terrestrial laser scanning, panoramic photogrammetry offers a significantly lower cost, which can be considered its main advantage. Another noteworthy finding is how well panoramic photogrammetry performed in spaces with unfavorable lighting conditions. During the orientation of the spherical images, no issues were encountered with incorrectly oriented images or with an insufficient number of tie points. On the other hand, the disadvantages of panoramic photogrammetry include lower accuracy, dependence on the number of images (with a reduced number of images leading to decreased reconstruction accuracy), and the necessity of introducing scale into the model. In this experiment, the scale was defined using five significant lengths measured with a measuring tape. It remains an open question about how the results would change if geodetic measurements were used for scaling. However, the use of geodetic measurements would undoubtedly increase the overall cost of work based on panoramic photogrammetry. A detailed comparison of panoramic photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning is provided in

Table 6.

Figure 15 presents the relationship between accuracy metrics and the number of spherical images. It should be noted that the optimal number of spherical images is difficult to estimate and depends on several factors, including the characteristics of the camera used, the shape and size of the room being documented, the texture of the object and lighting conditions.

Future work will involve testing other spherical cameras within low-cost panoramic photogrammetry and conducting experiments under different conditions. It is expected that improved lighting and more suitable surface textures will enable higher-quality reconstructions with increased accuracy, even with a smaller number of acquired images.

6. Conclusions

This study focused on testing low-cost panoramic photogrammetry for the reconstruction of interior spaces in the historic House of Samuel Mikovíni under challenging conditions (insufficient and variable lighting, flat textures, etc.) using the Ricoh Theta Z1 spherical camera. The scale for the photogrammetric reconstruction was established using five significant measured lengths by tape measure. The resulting difference point clouds, compared to the reference point cloud from terrestrial laser scanning, showed that panoramic photogrammetry can document interior spaces under difficult conditions with an accuracy of up to 0.05 m. Achieving this level of accuracy requires capturing a sufficient number of images, preferably from multiple height levels, and using the HDR capture mode to ensure adequate exposure even under poor and variable lighting conditions. A lower number of spherical images reduces not only the number of points in the reconstructed point cloud but also the overall accuracy of the interior reconstruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and O.B.; methodology, O.B.; validation, M.F., M.M.; formal analysis, M.F. and M.M.; investigation, O.B.; resources, O.B.; data curation, O.B. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.; writing—review and editing, M.F. and M.M.; visualization, O.B.; supervision, M.F.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.F. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic (grant no. 1/0618/23) and the Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic (grant no. 007STU-4/2023).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Michal Hrčka (Obnova s.r.o.) and Miloš Lukáč for providing the reference point cloud of the Samuel Mikovíni House acquired through terrestrial laser scanning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| VIS | Visual Inertial System |

| ICP | Iterative Closest Point |

References

- Pavelka, K.; Raeva, P.; Pavelka, K., Jr.; Kýhos, M.; Veselý, Z. Analysis of Data Joining from Different Instruments for Object Modelling. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2022, 43, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušeková, L.; Herich, P.; Pukanská, K.; Bartoš, K.; Kseňak, Ľ.; Šveda, J.; Fehér, J. Comparison of non-contact measurement technologies applied on the underground glacier—The choice for long-term monitoring of ice changes in Dobšiná ice cave. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Maas, H.-G. A Geometric Model for Linear-Array-Based Terrestrial Panoramic Cameras. Photogramm. Rec. 2006, 21, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, K.; Řezníček, J.; Bílá, Z.; Prunarová, L. Non Expensive 3D Documentation and Modelling of Historical Object and Archaeological Artefacts by Using Close Range Photogrammetry. Geoinformatics FCE CTU 2013, 10, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlesk, A.; Vach, K.; Holubec, P. Analysis of possibilities of low-cost photogrammetry for interior mapping. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzetti, L.; Previtali, M.; Roncoroni, F. Can we use low-cost 360 degree cameras to create accurate 3D models? Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Filippo, A.; Antinozzi, S.; Cappetti, N.; Villecco, F. Methodologies for assessing the quality of 3D models obtained using close-range photogrammetry. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 18, 5917–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herban, S.; Costantino, D.; Alfio, V.S.; Pepe, M. Use of Low-Cost Spherical Cameras for the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage Structures into 3D Point Clouds. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fangi, G.; Pierdicca, R.; Sturari, M.; Malinverni, E.S. Improving Spherical Photogrammetry Using 360° OMNI-Cameras: Use Cases and New Applications. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-2, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčiš, M.; Barták, P.; Valaška, D.; Fraštia, M.; Trhan, O. Use of Image Based Modelling for Documentation of Intricately Shaped Objects. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI-B5, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, T.; Tecklenburg, W. 3-D Object Reconstruction from Multiple-Station Panorama Imagery. Proc. Workshop 2004, 34, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, T.; Robson, S.; Kyle, S.; Boehm, J. Close-Range Photogrammetry and 3D Imaging, 2nd ed.; Whittles Publishing: Dunbeath, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D.; Schwalbe, E. Design and Testing of Mathematical Models for a Full-Spherical Camera on the Basis of a Rotating Linear Array Sensor and a Fisheye Lens. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Optical, Barcelona, Spain, 3–7 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Á.; Santo, A.; Ballesta, M.; Gil, A.; Payá, L. A Method for the Calibration of a LiDAR and Fisheye Camera System. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C. Analysis of fish-eye lens camera self-calibration. Sensors 2019, 19, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Li, H.; Song, R.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Song, B. Orthorectification of Fisheye Image under Equidistant Projection Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Beck, H. Geometrische und Stochastische Modelle für die Integrierte Auswertung Terrestrischer Laserscannerdaten und Photogrammetrischer Bilddaten; Deutsche Geodätische Kommission: Munich, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.C. Decentering Distortion of Lenses. Photogramm. Eng. 1966, 32, 444–462. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, S.; Arefi, H. Evaluation of Network Design and Solutions of Fisheye Camera Calibration for 3D Reconstruction. Sensors 2025, 25, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RICOH Imaging Company. RICOH THETA Z1—Specifications. Available online: https://us.ricoh-imaging.com/product/theta-z1/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Agisoft. Metashape, 2.1.0; Agisoft LLC: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2023.

- Leica Geosystems. Leica RTC360 Datasheet. 2018. Available online: https://leica-geosystems.com/products/laser-scanners/scanners/leica-rtc360 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Leica Geosystems. Cyclone REGISTER 360+, Version 2023.0; Leica Geosystems: Heerbrugg, Switzerland, 2023.

- CloudCompare. Version 2.13.beta. 2024. Available online: https://www.cloudcompare.org/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Figure 1.

Example of a spherical panoramic image (Ricoh Theta Z1 used).

Figure 1.

Example of a spherical panoramic image (Ricoh Theta Z1 used).

Figure 2.

Spherical image coordinates of a spherical panorama (angle units in radians).

Figure 2.

Spherical image coordinates of a spherical panorama (angle units in radians).

Figure 3.

Central projection (

left) vs. fish-eye projection (

right) [

17].

Figure 3.

Central projection (

left) vs. fish-eye projection (

right) [

17].

Figure 4.

Showcase of the interior spaces of the house of Samuel Mikovíni (as parts of HDR spherical images captured by Ricoh Theta Z1 camera).

Figure 4.

Showcase of the interior spaces of the house of Samuel Mikovíni (as parts of HDR spherical images captured by Ricoh Theta Z1 camera).

Figure 5.

(Left): Spherical camera Ricoh Theta Z1; (Right): Dense point cloud from panoramic photogrammetry (using all spherical images).

Figure 5.

(Left): Spherical camera Ricoh Theta Z1; (Right): Dense point cloud from panoramic photogrammetry (using all spherical images).

Figure 6.

Sparse point cloud with position of control and check scale bars.

Figure 6.

Sparse point cloud with position of control and check scale bars.

Figure 7.

(Left): Terrestrial laser scanner Leica RTC360; (Right): Point cloud from terrestrial laser scanning.

Figure 7.

(Left): Terrestrial laser scanner Leica RTC360; (Right): Point cloud from terrestrial laser scanning.

Figure 8.

Manual rough registration of point clouds—(Left): reference point cloud; (Right): point cloud to be aligned.

Figure 8.

Manual rough registration of point clouds—(Left): reference point cloud; (Right): point cloud to be aligned.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of the variable number of spherical images.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of the variable number of spherical images.

Figure 10.

Example of the positional arrangement of spherical images for rooms of different sizes.

Figure 10.

Example of the positional arrangement of spherical images for rooms of different sizes.

Figure 11.

Axonometric views of the panoramic point clouds for all six variants (units in meters).

Figure 11.

Axonometric views of the panoramic point clouds for all six variants (units in meters).

Figure 12.

Floor-plan views of the second floor (units in meters).

Figure 12.

Floor-plan views of the second floor (units in meters).

Figure 13.

Histograms of differences for individual variants (absolute distances in meters).

Figure 13.

Histograms of differences for individual variants (absolute distances in meters).

Figure 14.

Detail of point clouds from panoramic photogrammetry (units in meters).

Figure 14.

Detail of point clouds from panoramic photogrammetry (units in meters).

Figure 15.

Dependence between accuracy characteristics and the number of spherical images.

Figure 15.

Dependence between accuracy characteristics and the number of spherical images.

Table 1.

Mathematical equations of central projection and fish-eye projections.

Table 1.

Mathematical equations of central projection and fish-eye projections.

| Projection Type | Formula |

|---|

| Central | |

| Stereographic | |

| Equidistant | |

| Orthographic | |

Table 2.

Control and check scale bars information.

Table 2.

Control and check scale bars information.

| Accuracy Characteristics of Scale Application |

|---|

| Variant | Set Scale Bar Accuracy [m] | RMSE |

|---|

| Control Scale Bars [m] | Check Scale Bars [m] |

|---|

| 1 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.016 |

| 2 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.046 |

| 3 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.039 |

| 4 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.015 |

| 5 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.053 |

| 6 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.030 |

Table 3.

Automatic fine registration of point clouds.

Table 3.

Automatic fine registration of point clouds.

| Parameters from Automatic Registration via ICP Transformation |

|---|

| Variant | Number of Points | RMSE [m] |

|---|

| 1 | 100,000 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 100,000 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 100,000 | 0.11 |

| 4 | 100,000 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 100,000 | 0.21 |

| 6 | 100,000 | 0.22 |

Table 4.

Area per spherical image for each variant.

Table 4.

Area per spherical image for each variant.

| Total Area of the House of Samuel Mikovíni: 228.6 m2 |

|---|

| Variant | Number of Spherical Images | Area per Spherical Image [m2] |

|---|

| 1 | 252 | 0.9 |

| 2 | 168 | 1.4 |

| 3 | 104 | 2.2 |

| 4 | 58 | 3.9 |

| 5 | 114 | 2.0 |

| 6 | 65 | 3.5 |

Table 5.

Statistics of differences for individual variants.

Table 5.

Statistics of differences for individual variants.

| Statistics of Differences |

|---|

| Variant | MEAN [m] | STD [m] |

|---|

| 1 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| 2 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| 3 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| 6 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

Table 6.

Comparison of panoramic photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning.

Table 6.

Comparison of panoramic photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning.

Data Acquisition

Technology | Panoramic Photogrammetry | Terrestrial Laser Scanning |

|---|

| Acquisition Time | 1.5 h | 4 h |

| Processing Time | 2–3 h | 1–2 h |

| Accuracy | 0.05–0.15 m | 0.001–0.010 m |

| Detail | missing areas in poorly illuminated or low-texture regions | evenly distributed points at the specified resolution, full scene coverage |

| Cost | 1400 € | 70,000 € |

| Advantages | low cost, time-efficient, sufficient accuracy for basic interior documentation, easy data acquisition, compact 360° camera, suitable for realistic visualization of interiors | high accuracy and detail, suitable for detailed interior documentation, creation of 3D models and BIM models, independent of lighting conditions and surface texture |

| Disadvantages | requires additional scaling and variable texture of the object, lower reconstruction accuracy and detail, occurrence of artifacts and reconstruction errors in poorly lit or low-texture areas | high cost, difficult instrument handling, for color-accurate output requires integration with images, dependent on surface type and reflectivity |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |