An Integrated Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Impact of Soil Salinity on Rice Yield in Northeastern Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- evaluate the effectiveness of time-series Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 data combined with vegetation indices (NDVI, EVI) and ML algorithms for rice yield prediction;

- (ii)

- assess the integration of Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 with salinity-related indices for EC estimation; and

- (iii)

- examine how soil salinity during the seedling stage affects rice yield.

2. Method

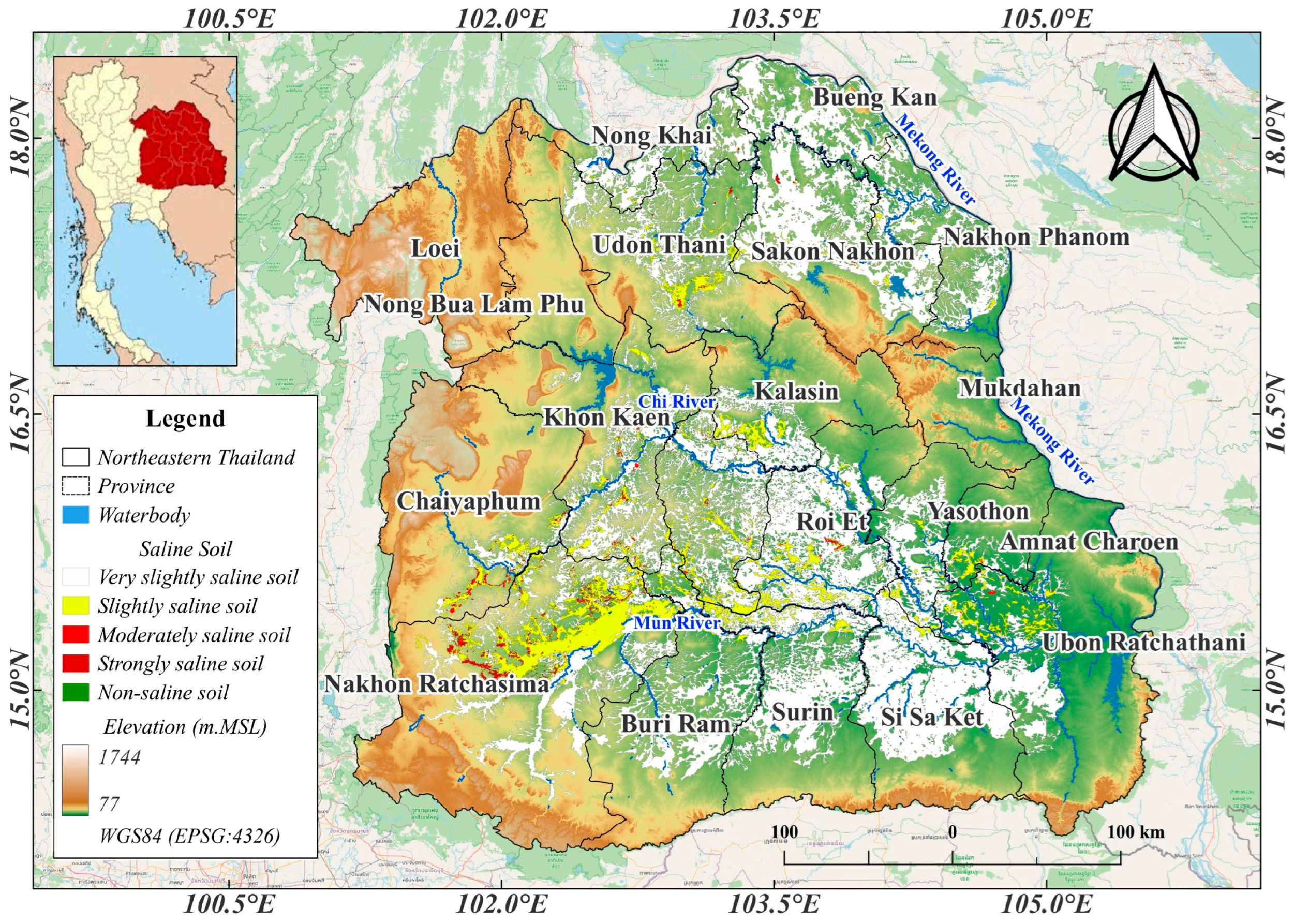

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Rice Growth Phenology and the Role of Vegetation Indices NDVI and EVI

2.3. Field Data Collection Strategy

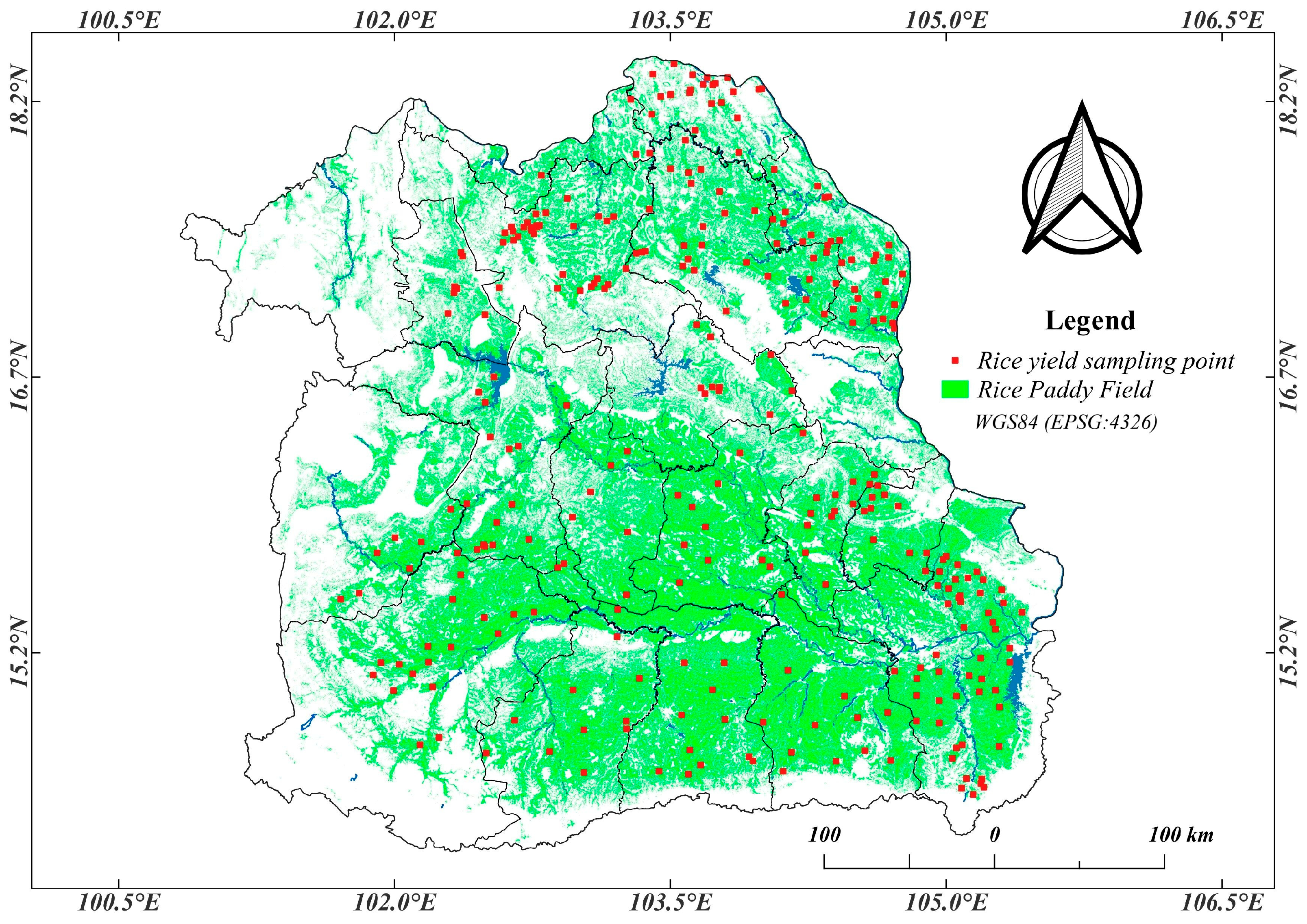

2.3.1. Rice Yield Ground Truth Data Collection

2.3.2. Soil Salinity Data Collection

2.4. Remote Sensing Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.5. Machine Learning Algorithms Implemented

2.5.1. Random Forest (RF)

2.5.2. Classification and Regression Trees (CART)

2.5.3. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

2.5.4. Model Configuration and Evaluation

2.6. Variable Reduction and Selection of Optimal Predictors

2.7. Data Processing and Data Analysis

2.7.1. Predicting Rice Yield Using Monthly Image Composites from Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Data

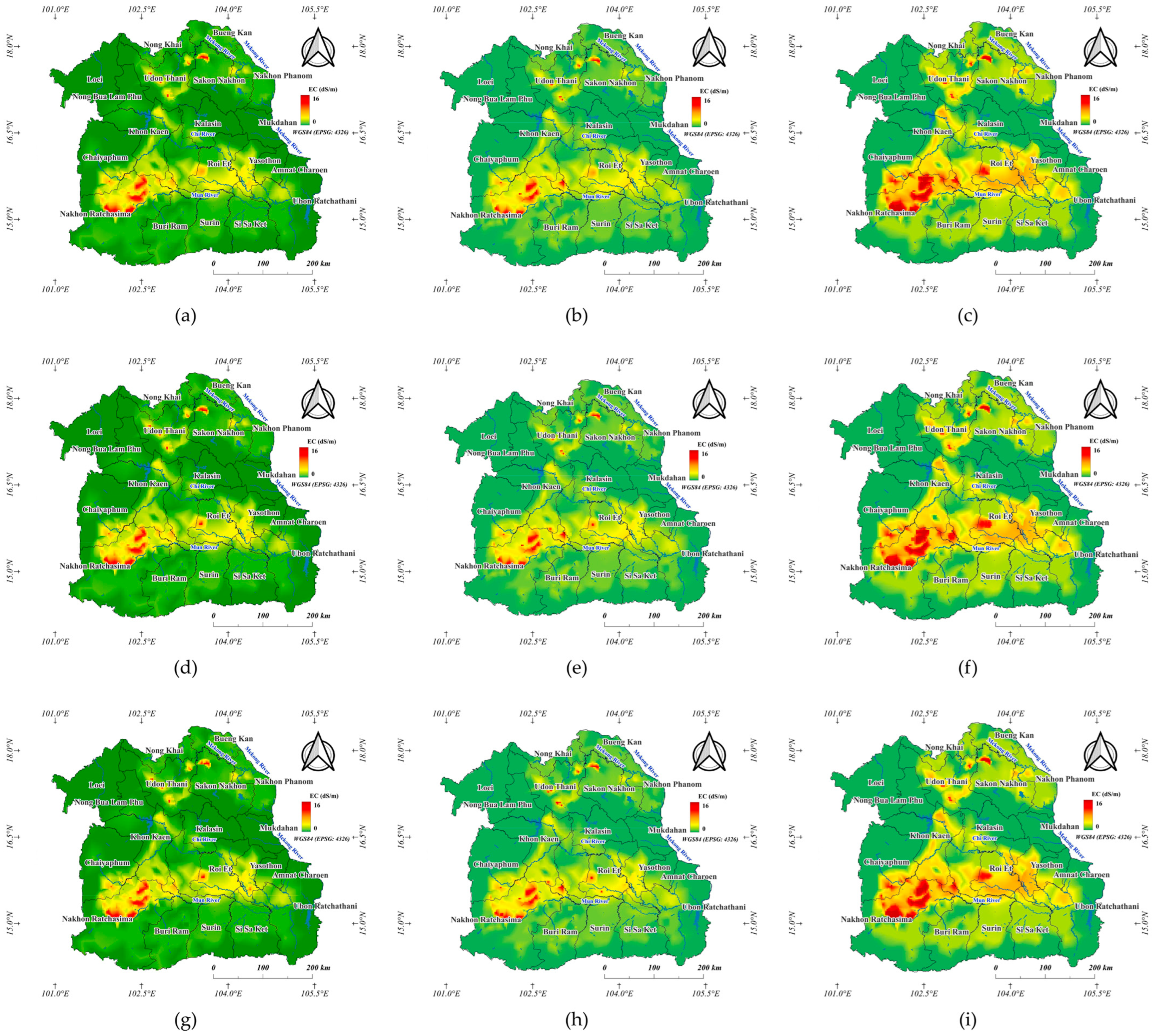

2.7.2. Soil Salinity Mapping

2.7.3. Procedure for Rice Yield and Soil EC Correlation Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Rice Yield Model

3.1.1. Vegetation Index Dynamics Across Rice Growth Stages

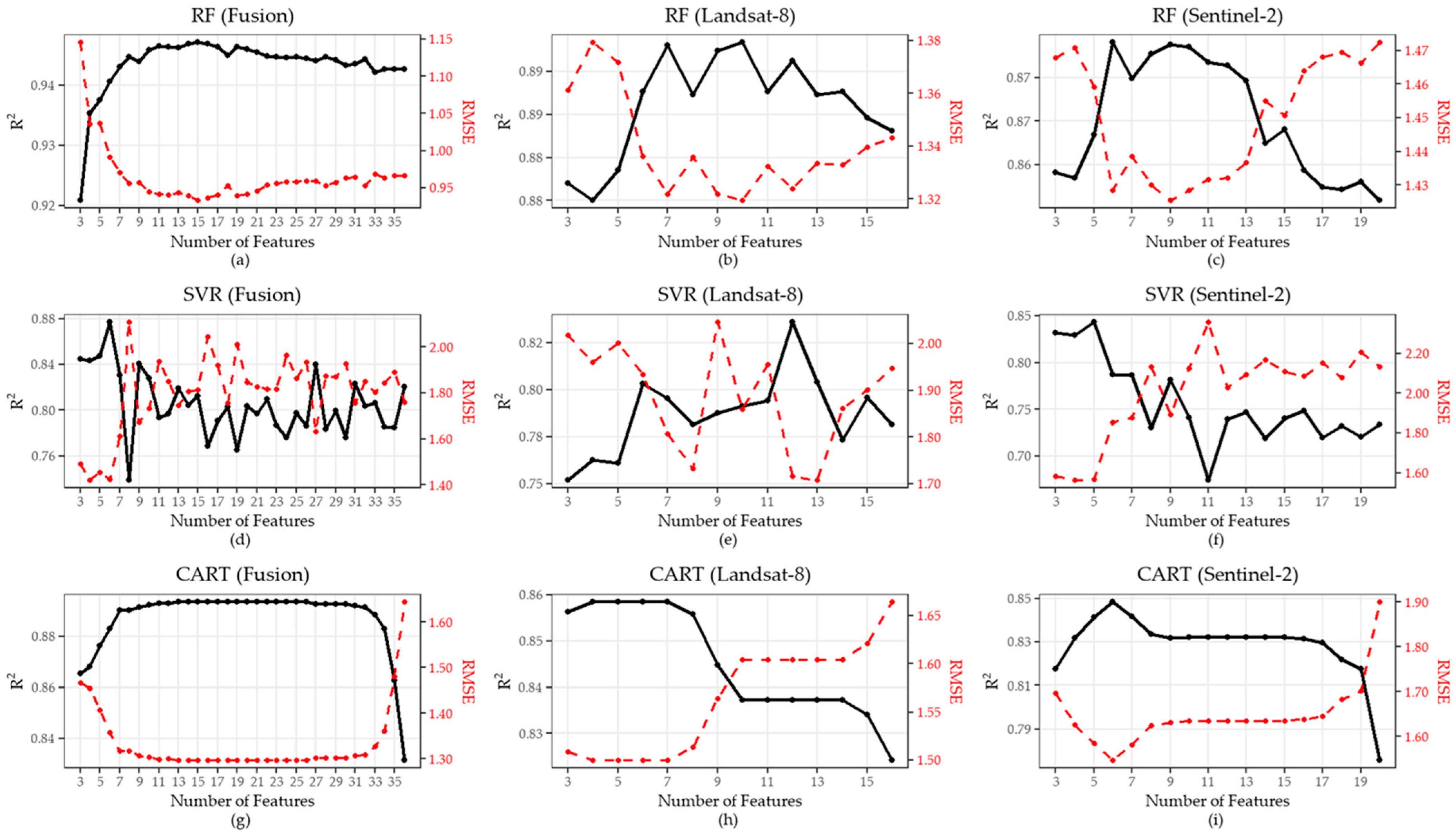

3.1.2. Variable Reduction Results for Rice Yield Models

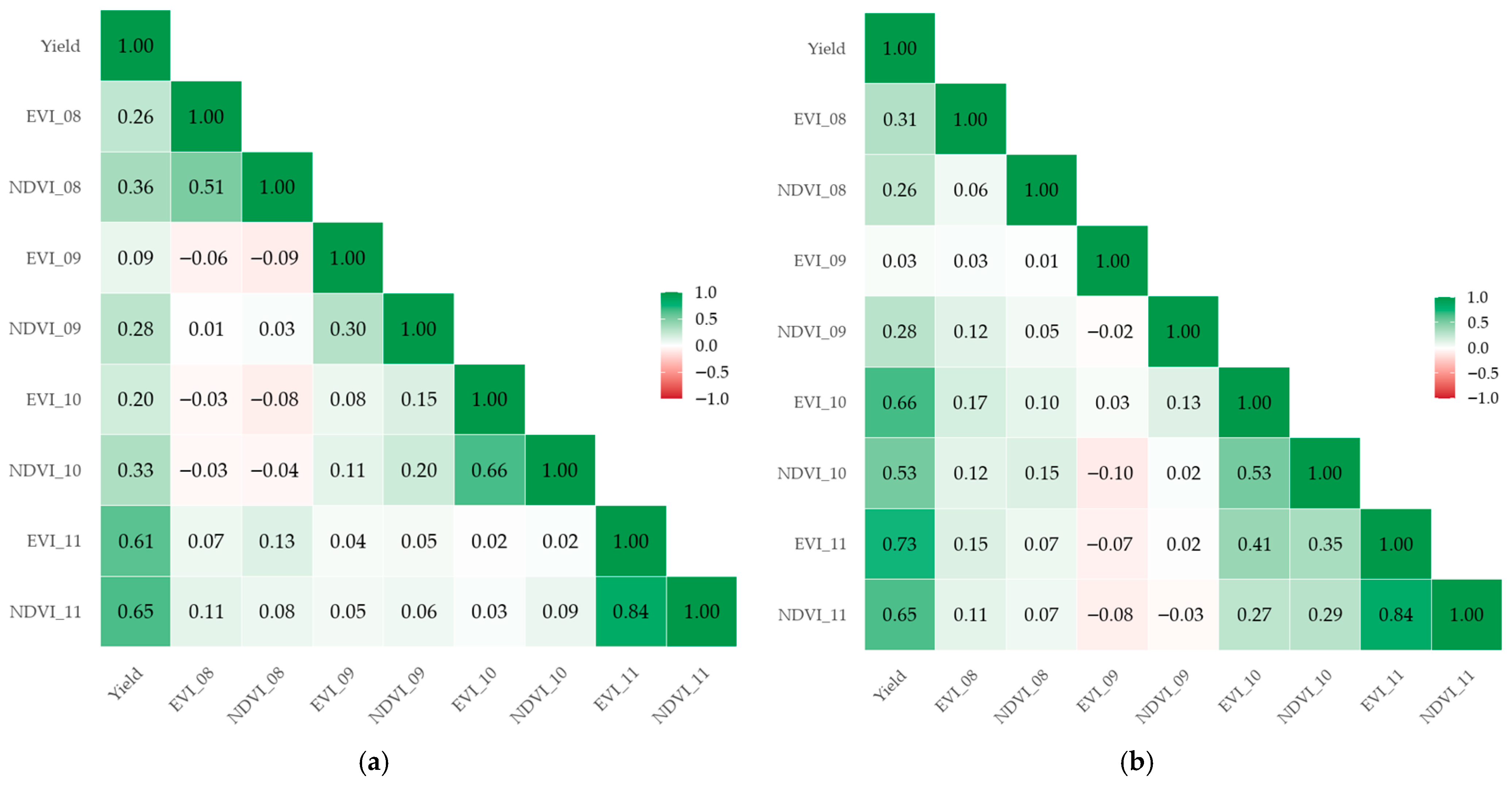

3.1.3. Correlation Analysis of Rice Yield and Satellite Derived Variables

3.1.4. Final Feature Selection for Rice Yield Prediction

3.1.5. Variable Importance Analysis and Model Interpretability for Rice Yield Prediction

3.1.6. Model Performance for Rice Yield Prediction

3.2. Soil Salinity Estimation Models

3.2.1. Variable Reduction Results for Soil Salinity Models

3.2.2. Correlation Analysis of EC and Satellite Derived Variables

3.2.3. Final Feature Selection for Soil Salinity Models

3.2.4. Variable Importance Analysis and Model Interpretability for Soil Salinity

3.2.5. Model Performance for Soil Salinity Estimation

3.3. Correlation Between Rice Yield and Soil Electrical Conductivity (EC)

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Evaluation of Machine Learning Models for Rice Yield Prediction

4.2. Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Models for Soil Salinity Estimation

4.3. Relationship Between Soil Salinity and Rice Yield

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahid, S.A.; Zaman, M.; Heng, L. Soil Salinity: Historical Perspectives and a World Overview of the Problem. In Guideline for Salinity Assessment, Mitigation and Adaptation Using Nuclear and Related Techniques; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 72, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Flowers, T.J. The physiology and molecular biology of the effects of salinity on rice. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, N.C. Soil Factors that Influence Rice Production. In Proceedings of Symposium on Paddy Soils; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felkner, J.; Tazhibayeva, K.; Townsend, R. Impact of Climate Change on Rice Production in Thailand. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattan, S.R.; Zeng, L.; Shannon, M.C.; Roberts, S.R. Rice is more sensitive to salinity than previously thought. Calif. Agric. 2002, 56, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshori, M.F.; Purwoko, B.S.; Dewi, I.S.; Ardie, S.W.; Suwarno, W.B.; Safitri, H. Determination of selection criteria for screening of rice genotypes for salinity tolerance. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2018, 50, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, D.W. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils. Agron. J. 1954, 46, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.V.; Grattan, S.R. Crop Yields as Affected by Salinity. In Agronomy Monographs; Skaggs, R.W., Van Schilfgaarde, J., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2015; pp. 55–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Shannon, M.C. Effects of Salinity on Grain Yield and Yield Components of Rice at Different Seeding Densities. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Shannon, M.C. Salinity Effects on Seedling Growth and Yield Components of Rice. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kour, S.; Gupta, M.; Kachroo, D.; Singh, H. Influence of rice varieties and fertility levels on performance of rice and soil nutrient status under aerobic conditions. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2017, 9, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichaidist, B.; Intrman, A.; Puttrawutichai, S.; Rewtragulpaibul, C.; Chuanpongpanich, S.; Suksaroj, C. The effect of irrigation techniques on sustainable water management for rice cultivation system—A review. Appl. Environ. Res. 2023, 45, e024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkolnithithada, W.; Nontapun, J.; Kaewplang, S. Rice yield estimation based on machine learning approaches using MODIS 250 m data. Eng. Access 2023, 9, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Siyal, A.A.; Dempewolf, J.; Becker-Reshef, I. Rice yield estimation using Landsat ETM+ Data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2015, 9, 095986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htun, A.M.; Shamsuzzoha, M.; Ahamed, T. Rice yield prediction model using normalized vegetation and water indices from Sentinel-2A satellite imagery datasets. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2023, 7, 491–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; Shi, W.; Dong, Y.; Paringer, R. Random Forest for rice yield mapping and prediction using Sentinel-2 data with Google Earth Engine. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 70, 2443–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.-T.; Chen, C.-F.; Chen, C.-R.; Guo, H.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Chen, S.-L.; Lin, H.-S.; Chen, S.-H. Machine learning approaches for rice crop yield predictions using time-series satellite data in Taiwan. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 7868–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.-T.; Chen, C.-F.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Toscano, P.; Chen, C.-R.; Chen, S.-L.; Tseng, K.-H.; Syu, C.-H.; Guo, H.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-T. Field-scale rice yield prediction from Sentinel-2 monthly image composites using machine learning algorithms. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 69, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanto, A.W.; Putri, S.R. Estimating Rice production using machine learning models on multitemporal Landsat-8 satellite images (case study: Ngawi regency, East Java, Indonesia). In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Computational Intelligence (CyberneticsCom), Malang, Indonesia, 16–18 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyana, A.; Hanchoowong, R.; Srihanu, N.; Prasanchum, H.; Kangrang, A.; Hormwichian, R.; Kaewplang, S.; Koedsin, W.; Huete, A. Leveraging Remotely Sensed and Climatic Data for Improved Crop Yield Prediction in the Chi Basin, Thailand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Lan, S.; Gao, T.; Li, M. Winter wheat yield prediction using integrated Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 vegetation index time-series data and machine learning algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, M.S.; Kübert-Flock, C.; Dahms, T.; Rummler, T.; Arnault, J.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Ullmann, T. Evaluation of MODIS, Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 data for accurate crop yield predictions: A case study using STARFM NDVI in Bavaria, Germany. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Ustin, S.; Qiu, Z.; Xu, M.; Guo, D. Assessment of the effectiveness of spatiotemporal fusion of multi-source satellite images for cotton yield estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J.; Arosemena-Jované, J.T.; Cantón-Martínez, S.; Pérez-Porras, F.; Torres-Sánchez, J. Enhancing Crop Yield Estimation in Spinach Crops Using Synthetic Aperture Radar-Derived Normalized Difference Vegetation Index: A Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Fusion Approach. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyono, T.D.; Quicho, E.D.; Gatti, L.; Campos-Taberner, M.; Busetto, L.; Collivignarelli, F.; García-Haro, F.J.; Boschetti, M.; Khan, N.I.; Holecz, F. Spatial rice yield estimation based on MODIS and Sentinel-1 SAR data and ORYZA crop growth model. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Liao, J. Paddy Rice Mapping in Hainan Island Using Time-Series Sentinel-1 SAR Data and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, N.; Adak, S.; Das, D.K.; Sahoo, R.N.; Mukherjee, J.; Kumar, A.; Chinnusamy, V.; Das, B.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Rajashekara, H.; et al. Spectral characterization and severity assessment of rice blast disease using univariate and multivariate models. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1067189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, R.; Khan, Z. Predicting Rice Yield Using Multi-Temporal Vegetation Indices and Machine Learning: A Comparative Study of Random Forest and Support Vector Regression Models. Front. Comput. Spat. Intell. 2024, 2, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Taghadosi, M.M.; Hasanlou, M.; Eftekhari, K. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, S.; Yildirim, A.; Gorji, T.; Hamzehpour, N.; Tanik, A.; Sertel, E. Assessing the performance of machine learning algorithms for soil salinity mapping in Google Earth Engine platform using Sentinel-2A and Landsat-8 OLI data. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 69, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Y.U.; Shahbaz, M.; Asif, H.S.; Al-Laith, A.; Alsabban, W.H. Spatial mapping of soil salinity using machine learning and remote sensing in Kot Addu, Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tashpolat, N. Remote Sensing Monitoring of Soil Salinity in Weigan River–Kuqa River Delta Oasis Based on Two-Dimensional Feature Space. Water 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandak, S.; Movahedi-Naeini, S.A.; Mehri, S.; Lotfata, A. A longitudinal analysis of soil salinity changes using remotely sensed imageries. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Xue, J.; Peng, J.; Biswas, A.; He, Y.; Shi, Z. Integrating remote sensing and landscape characteristics to estimate soil salinity using machine learning methods: A case study from Southern Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholdorov, S.; Lakshmi, G.; Jabbarov, Z.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yamashita, M.; Samatov, N.; Katsura, K. Analysis of irrigated salt-affected soils in the Central Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan, using Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 satellite images, laboratory studies, and spectral index-based approaches. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Frappart, F.; Taghizadeh, R.; Zhang, X.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Xue, J.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, J.; et al. Global Soil Salinity Estimation at 10 m Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shi, T.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, C. Mapping Coastal Soil Salinity and Vegetation Dynamics Using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data Fusion with Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 14203–14214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunin, S. Characteristics and Management of Salt-Affected Soils in the Northeast of Thailand; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1984; pp. 336–351. [Google Scholar]

- Sujariya, S.; Jongrungklang, N.; Jongdee, B.; Inthavong, T.; Budhaboon, C.; Fukai, S. Rainfall variability and its effects on growing period and grain yield for rainfed lowland rice under transplanting system in Northeast Thailand. Plant Prod. Sci. 2020, 23, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, F.; Pullanagari, R.; Kereszturi, G.; Procter, J. Mapping a cloud-free rice growth stages using the integration of PROBA-V and Sentinel-1 and its temporal correlation with sub-district statistics. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.I.; Six, J.; Plant, R.E.; Peña, J.M. Mapping crop calendar events and phenology-related metrics at the parcel level by object-based image analysis (OBIA) of MODIS-NDVI time-series: A case study in central California. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Friedl, M.A.; Schaaf, C.B.; Strahler, A.H.; Hodges, J.C.; Gao, F.; Reed, B.C.; Huete, A. Monitoring vegetation phenology using MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 84, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; Volume 3, p. 307â. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksungnoen, N.; Andriyas, T.; Andriyas, S. ECe prediction from EC1: 5 in inland salt-affected soils collected from Khorat and Sakhon Nakhon basins, Thailand. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2018, 49, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFEETERS, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 77, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, H.; Walter, C. Detecting salinity hazards within a semiarid context by means of combining soil and remote-sensing data. Geoderma 2006, 134, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Khan, S. Using remote sensing techniques for appraisal of irrigated soil salinity. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM); Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2007; pp. 2632–2638. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package, Version 1.1.4; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Data Analysis. In ggplot2; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package, 487 (Version 0.94); UTC: Chattanooga, TN, USA, 2024; “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix.

- Xie, Y. Dynamic Documents with R and Knitr; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therneau, T.; Atkinson, B. R Package, Version 4.1-24. rpart: Recursive partitioning and regression trees. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Xie, Y. R Package, Version 2025;1:1.; UTC: Chattanooga, TN, USA, knitr: A general-purpose package for dynamic report generation in R (Version 1.50).

- Wickham, H.; Vaughan, D.; Girlich, M. Computer Software, Version 1.3. 1. tidyr: Tidy messy data. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyr/index.html (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Wickham, H. Reshaping data with the reshape package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Jianli, D. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for soil salinity predictions in three dryland oases located in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XJUAR) of China. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shi, Z.; Biswas, A.; Yang, S.; Ding, J.; Wang, F. Updated information on soil salinity in a typical oasis agroecosystem and desert-oasis ecotone: Case study conducted along the Tarim River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 135387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, B. Global revisit interval analysis of Landsat-8-9 and Sentinel-2A-2B data for terrestrial monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverie, M.; Ju, J.; Masek, J.G.; Dungan, J.L.; Vermote, E.F.; Roger, J.-C.; Skakun, S.V.; Justice, C. The Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 surface reflectance data set. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 219, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Useya, J.; Chen, S. Comparative performance evaluation of pixel-level and decision-level data fusion of Landsat 8 OLI, Landsat 7 ETM+ and Sentinel-2 MSI for crop ensemble classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 4441–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Tao, X.; Wang, B.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X. In-season mapping of rice yield potential at jointing stage using Sentinel-2 images integrated with high-precision UAS data. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, M. Mapping paddy rice by the object-based random forest method using time series Sentinel-1/Sentinel-2 data. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 64, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Coca, L.I.; García González, M.T.; Gil Unday, Z.; Jiménez Hernández, J.; Rodríguez Jáuregui, M.M.; Fernández Cancio, Y. Effects of sodium salinity on rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivation: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Ikeda, T.; Itoh, R. Effect of NaCl salinity on photosynthesis and dry matter accumulation in developing rice grains. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1999, 42, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutts, S.; Kinet, J.M.; Bouharmont, J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Ann. Bot. 1996, 78, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, S.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Hernández-Aragón, L. Osmotic stress affects growth, content of chlorophyll, abscisic acid, Na+, and K+, and expression of novel NAC genes in contrasting rice cultivars. Biol. Plant. 2018, 62, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, T.; Feng, W.; Han, L.; Gao, R.; Wang, F.; Ma, S.; Han, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S. Integrating Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1/2 Vegetation Signatures with Machine Learning for Enhanced Soil Salinity Mapping Accuracy in Coastal Irrigation Zones: A Case Study of the Yellow River Delta. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Han, J.; Liu, D. Estimating salt content of vegetated soil at different depths with Sentinel-2 data. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, R.; de Lima, I.P. Sentinel-2 satellite imagery-based assessment of soil salinity in irrigated rice fields in Portugal. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Bai, T.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Cong, L.; Qu, X.; Li, X. Extraction and analysis of soil salinization information in an alar reclamation area based on spectral index modeling. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, D.; Li, F.; Wu, F.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Kou, C.; Li, C. Comparison of machine learning methods for predicting soil total nitrogen content using Landsat-8, Sentinel-1, and Sentinel-2 images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2907. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, H. Exploring the influencing factors in identifying soil texture classes using multitemporal landsat-8 and sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5571. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Han, L.; Liu, L.; Bai, C.; Ao, J.; Hu, H.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Wei, Y. Advancements and Perspective in the Quantitative Assessment of Soil Salinity Utilizing Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Algorithms: A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, I.; Walter, C.; Michot, D.; Adam Boukary, I.; Nicolas, H.; Pichelin, P.; Guéro, Y. Soil Salinity assessment in irrigated paddy fields of the niger valley using a four-year time series of sentinel-2 satellite images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3399. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-González, J.; Angelats, E.; Martínez-Eixarch, M.; Alcaraz, C. Monitoring rice crop and yield estimation with Sentinel-2 data. Field Crops Res. 2022, 281, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.P. Relating soil electrical conductivity to remote sensing and other soil properties for assessing soil salinity in northeast Thailand. Land Degrad. Dev. 2006, 17, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, R.; Srisutham, M.; Nontasri, T.; Sritumboon, S.; Maki, M.; Yoshida, K.; Oki, K.; Homma, K. Rice production in farmer fields in soil salinity classified areas in Khon Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munns, R.; Passioura, J.B.; Colmer, T.D.; Byrt, C.S. Osmotic adjustment and energy limitations to plant growth in saline soil. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaque, M.A.; Talukder, N.M.; Islam, M.T.; Dutta, R.K. Salinity effect on mineral nutrient distribution along roots and shoots of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes differing in salt tolerance. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2011, 57, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Suarez, D.L. Interactive effects of pH, EC and nitrogen on yields and nutrient absorption of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 194, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, E.; Suarez-Gutierrez, L.; Jézéquel, A.; Lehner, F.; Vrac, M.; Yiou, P.; Zscheischler, J. Advancing research on compound weather and climate events via large ensemble model simulations. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murynin, A.; Gorokhovskiy, K.; Bondur, V.; Ignatiev, V. Analysis of large long-term remote sensing image sequence for agricultural yield forecasting. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Image Mining. Theory and Applications VISIGRAPP, Barcelona, Spain, 23 February 2013; pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

| Data | Vegetation | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat-8 | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | [44] | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | [45] | ||

| Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | [47] | ||

| Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) | [48] | ||

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (GNDVI) | [49] | ||

| Sentinel-2 | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index 1 (NDVI) | [44] | |

| Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) | [48] | ||

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | [45] | ||

| Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | [47] | ||

| Salinity Index 1 (SI1) | [50] | ||

| Salinity Index 2 (SI2) | [50] | ||

| Salinity Index 3 (SI3) | [51] | ||

| Salinity Index 4 (SI4) | [52] | ||

| Salinity Index 5 (SI5) | [51] |

| Dataset | Source | Spectral–Temporal Data |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Landsat-8 | Seasonal: NDVI and EVI |

| 2 | Sentinel-2 | Seasonal: NDVI and EVI |

| 3 | Landsat-8 + Sentinel-2 | Seasonal: (S-2) NDVI and EVI, (L-8) NDVI and EVI |

| Dataset | Source | Spectral–Temporal Data |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Landsat-8 | B2-B7, NDVI, SAVI, EVI, GNDVI, NDWI, SI1-SI5 |

| 2 | Sentinel-2 | B2-8A, B11-12, NDVI, SAVI, EVI, GNDVI, NDWI, SI1- SI5 |

| 3 | Landsat-8 + Sentinel-2 | L8: B2-B7, S2: B2-8A, B11-12, NDVI, SAVI, EVI, GNDVI, NDWI, SI1-SI5 S2: B2-B8A, SI1-SI5 |

| Dataset | Random Forest (RF) | Classification and Regression Trees (CART) | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Validation | Training | Validation | Training | Validation | |||||||

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| 1 | 0.96 | 0.10 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.37 |

| 2 | 0.83 | 0.13 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.42 |

| 3 | 0.97 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.19 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 0.33 |

| Dataset | Random Forest (RF) | Classification and Regression Trees (CART) | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Validation | Training | Validation | Training | Validation | |||||||

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| 1 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.83 | 1.36 | 0.89 | 1.17 | 0.78 | 1.64 | 0.89 | 1.26 | 0.77 | 1.68 |

| 2 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 1.46 | 0.80 | 1.56 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 0.80 | 1.72 | 0.76 | 1.82 |

| 3 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.33 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.35 |

| Count | Mean | Std | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (ton/ha) | 5000 | 2.82 | 0.60 | 1.01 | 3.71 |

| EC during the seedling stage (dS/m) | 5000 | 5.98 | 3.76 | 3.15 | 22.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nontapon, J.; Srihanu, N.; Bhumiphan, N.; Kaewhanam, N.; Kangrang, A.; Bhurtyal, U.; KC, N.; Kaewplang, S.; Huete, A. An Integrated Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Impact of Soil Salinity on Rice Yield in Northeastern Thailand. Geomatics 2025, 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040080

Nontapon J, Srihanu N, Bhumiphan N, Kaewhanam N, Kangrang A, Bhurtyal U, KC N, Kaewplang S, Huete A. An Integrated Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Impact of Soil Salinity on Rice Yield in Northeastern Thailand. Geomatics. 2025; 5(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleNontapon, Jurawan, Neti Srihanu, Niwat Bhumiphan, Nopanom Kaewhanam, Anongrit Kangrang, Umesh Bhurtyal, Niraj KC, Siwa Kaewplang, and Alfredo Huete. 2025. "An Integrated Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Impact of Soil Salinity on Rice Yield in Northeastern Thailand" Geomatics 5, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040080

APA StyleNontapon, J., Srihanu, N., Bhumiphan, N., Kaewhanam, N., Kangrang, A., Bhurtyal, U., KC, N., Kaewplang, S., & Huete, A. (2025). An Integrated Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Impact of Soil Salinity on Rice Yield in Northeastern Thailand. Geomatics, 5(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040080