Structural Change in Romanian Land Use and Land Cover (1990–2018): A Multi-Index Analysis Integrating Kolmogorov Complexity, Fractal Analysis, and GLCM Texture Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

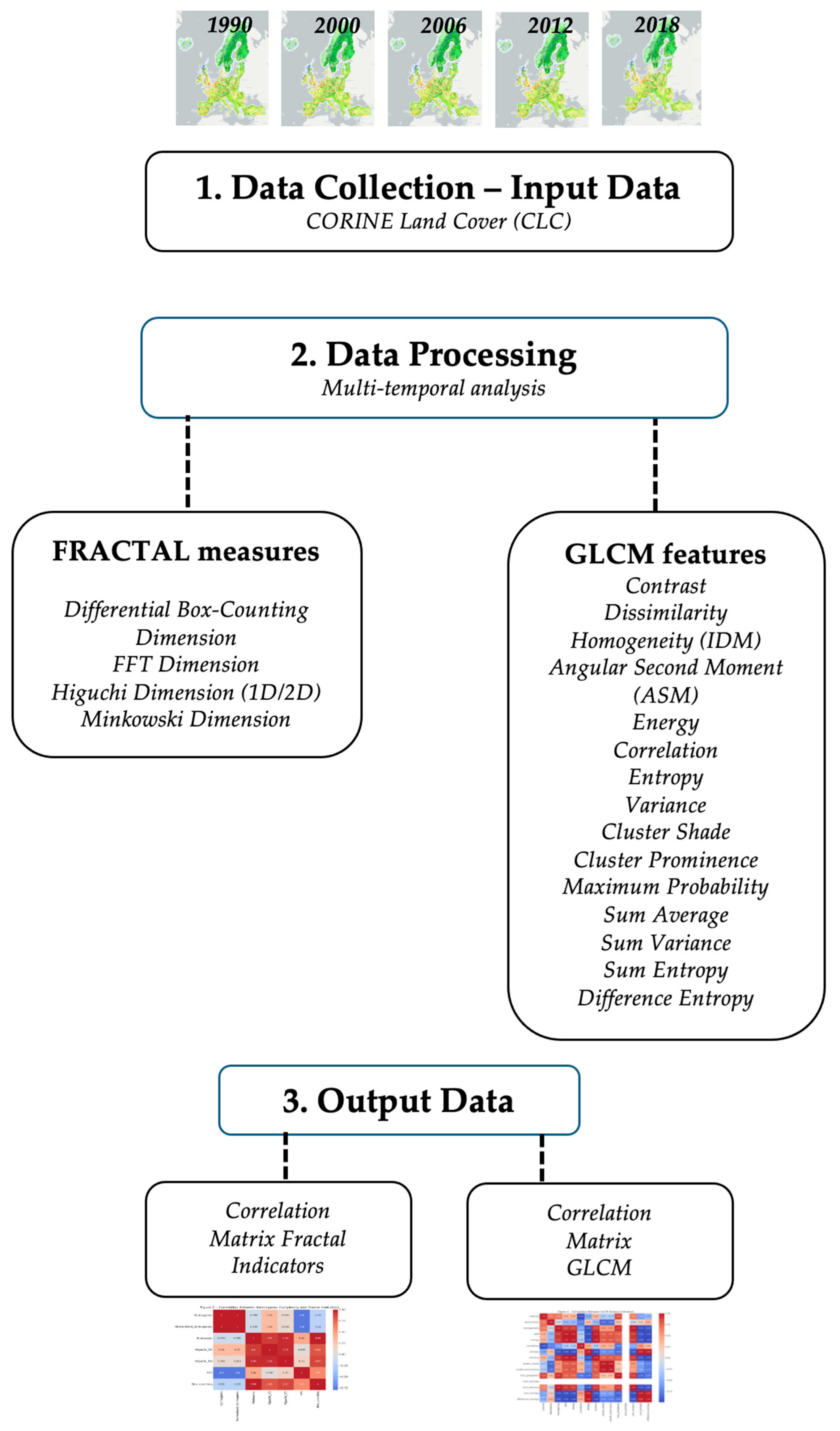

2. Materials and Methods

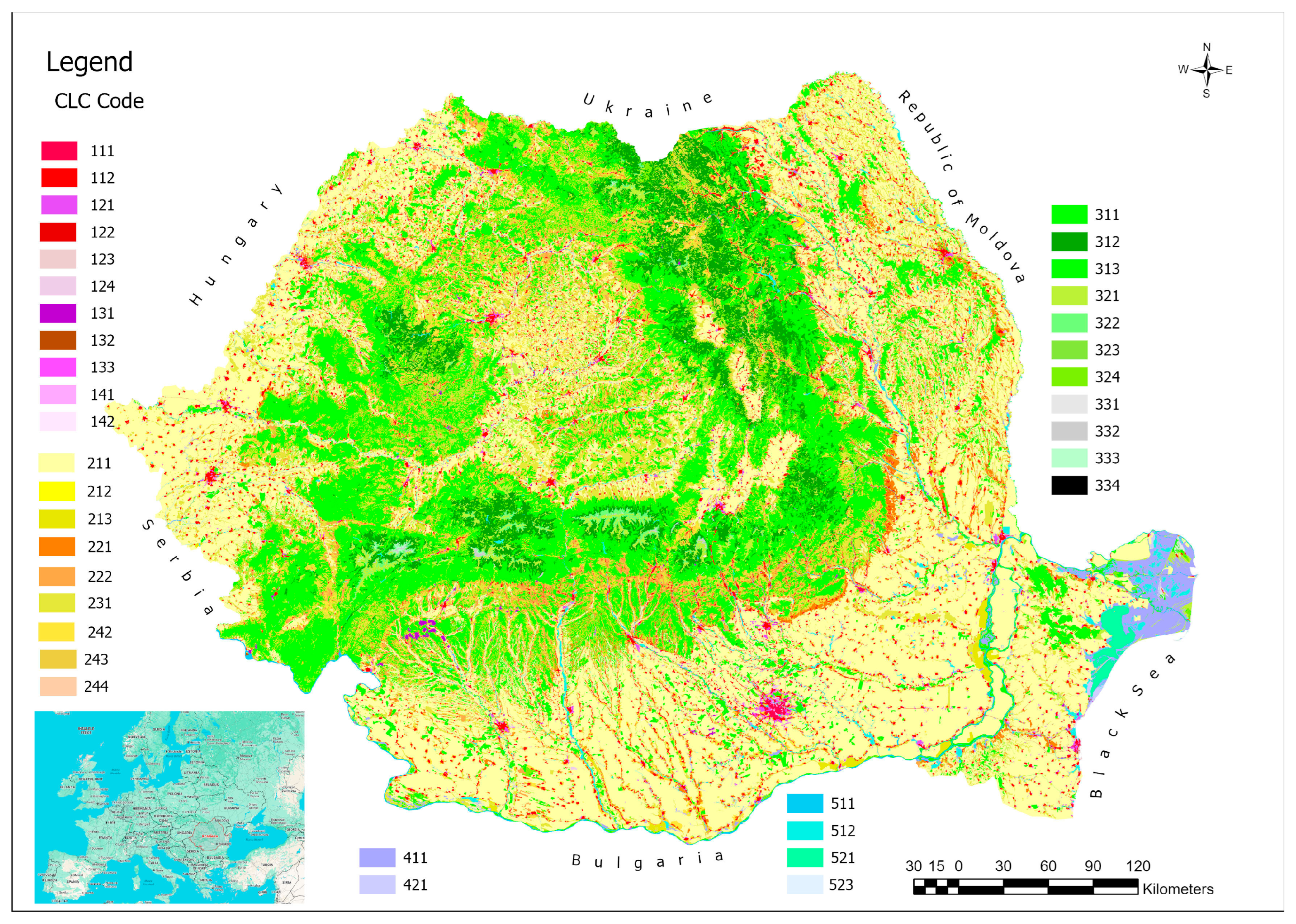

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

2.2. Data Processing

2.3. Index Framework and Computational Approach

| Name of Fractal Measures | Meaning/Definition and Formula | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Box-Counting Dimension | Estimate spatial fractality by covering the set with boxes of side ε and counting occupied boxes N(ε). Dimension: D = lim_{ε→0} [ log N(ε)/log(1/ε)]. Adaptation for grayscale images: partition into spatial cells, quantize grey levels into vertical stacks; FD obtained from the slope of the log–log plot of local sums vs. box size. | [36,37] |

| [38,39] | ||

| FFT Dimension | Based on power spectrum S(f) ∝ f^{−β}. For 2D surfaces: D ≈ 4 − β/2, where β is the slope in the log S vs. log f plot. | [40] |

| Higuchi Dimension (1D/2D) | FD estimated from curve length L(k) at discrete scales k; the slope of log L(k) vs. log(1/k) yields D. Two-dimensional variants use profiles (rows/columns) or the whole surface. | [41,42,43,44] |

| Minkowski Dimension | Dilate the set with a structuring element of radius r and measure the dilated volume/area V(r). Relation: V(r) ∝ r^{d − D} ⇒ D = d − d(log V(r))/d(log r), where d is the embedding dimension. | [45] |

| GLCM Measures | Meaning/Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Heterogeneity: Σ_{i,j} (i − j)^2⋯p(i,j). | [46] |

| Dissimilarity | Linear version of contrast: Σ_{i,j} |i − j|⋯p(i,j). | |

| Homogeneity (IDM) | Closeness to the diagonal: Σ_{i,j} p(i,j)/[1 + (i − j)^2]. | |

| Angular Second Moment (ASM) | Texture uniformity: Σ_{i,j} p(i,j)^2. | |

| Energy | √ASM (measure of order). | |

| Correlation | Linear dependency: Σ_{i,j} ((i − μ_x)(j − μ_y)/(σ_x σ_y))⋯p(i,j). | |

| Entropy | Randomness: −Σ_{i,j} p(i,j)⋯log p(i,j). | |

| Variance | Grey-level dispersion (via marginals): Σ_i (i − μ_x)^2 p_x(i) (analogous for y). | |

| Cluster Shade | Asymmetry: Σ_{i,j} (i + j − μ_x − μ_y)^3⋯p(i,j). | |

| Cluster Prominence | Peakedness: Σ_{i,j} (i + j − μ_x − μ_y)^4⋯p(i,j). | |

| Maximum Probability | Most frequent pair: max_{i,j} p(i,j). | |

| Sum Average | Mean of the sum: Σ_k k⋯p_{x + y}(k). | |

| Sum Variance | Variance of the sum: Σ_k (k − μ_{x + y})^2⋯p_{x + y}(k). | |

| Sum Entropy | Entropy of the sum: −Σ_k p_{x + y}(k)⋯log p_{x + y}(k). | |

| Difference Entropy | Entropy of the difference: −Σ_k p_{|x − y|}(k)⋯log p_{|x − y|}(k). |

2.4. Comparative and Temporal Analysis

3. Results

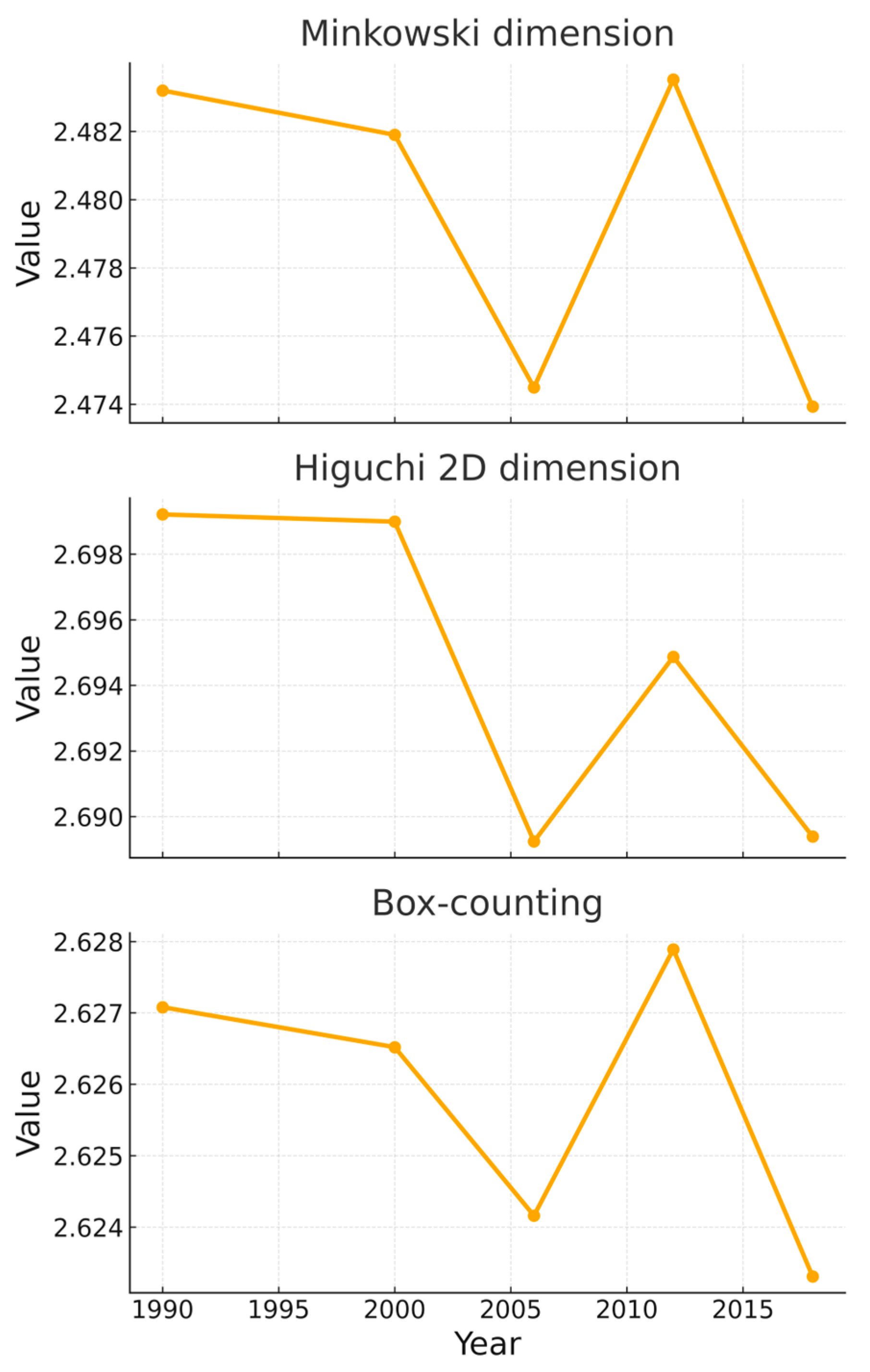

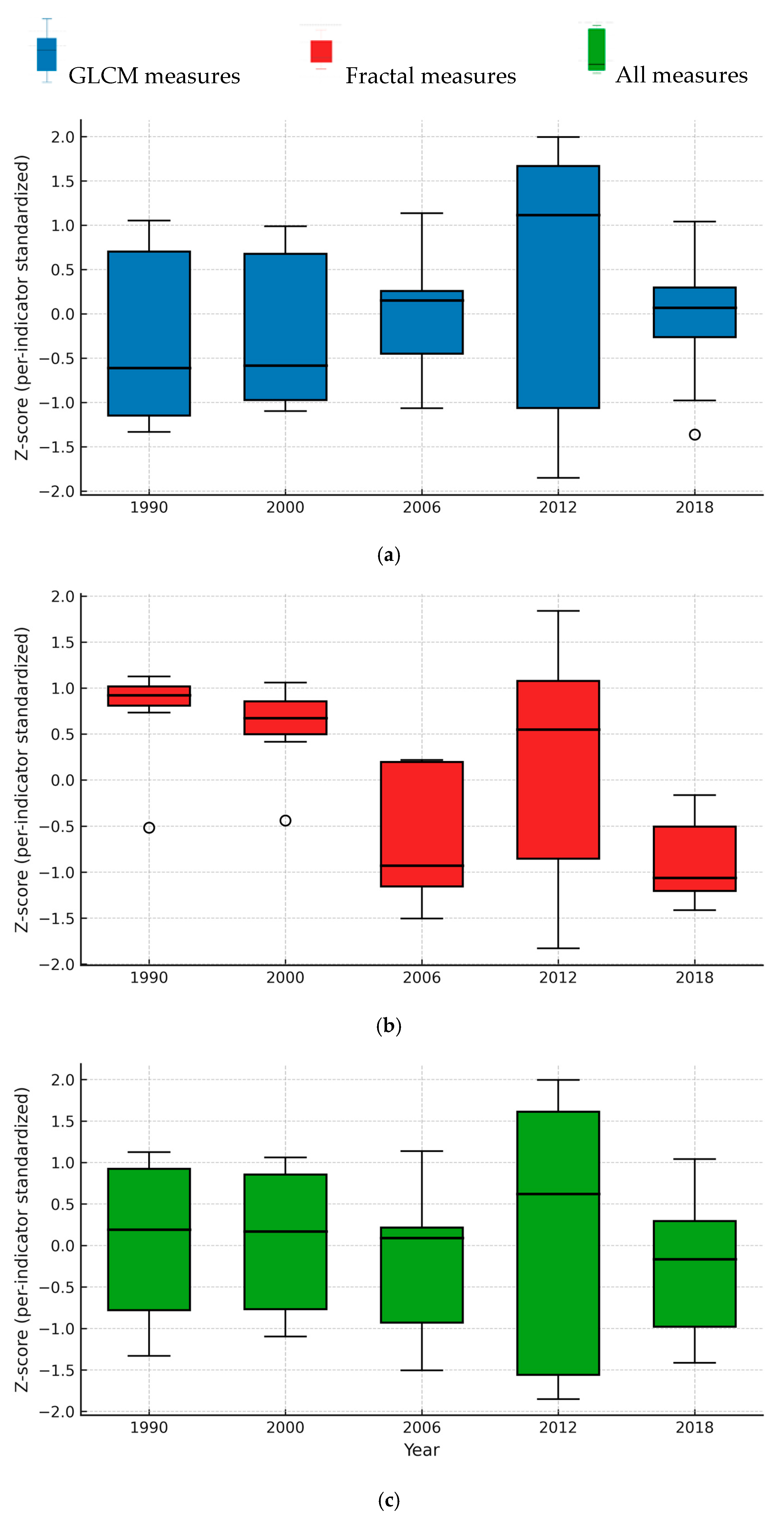

3.1. Dynamics of Fractal and GLCM Texture Measures

3.1.1. Dynamics of Fractal Measures

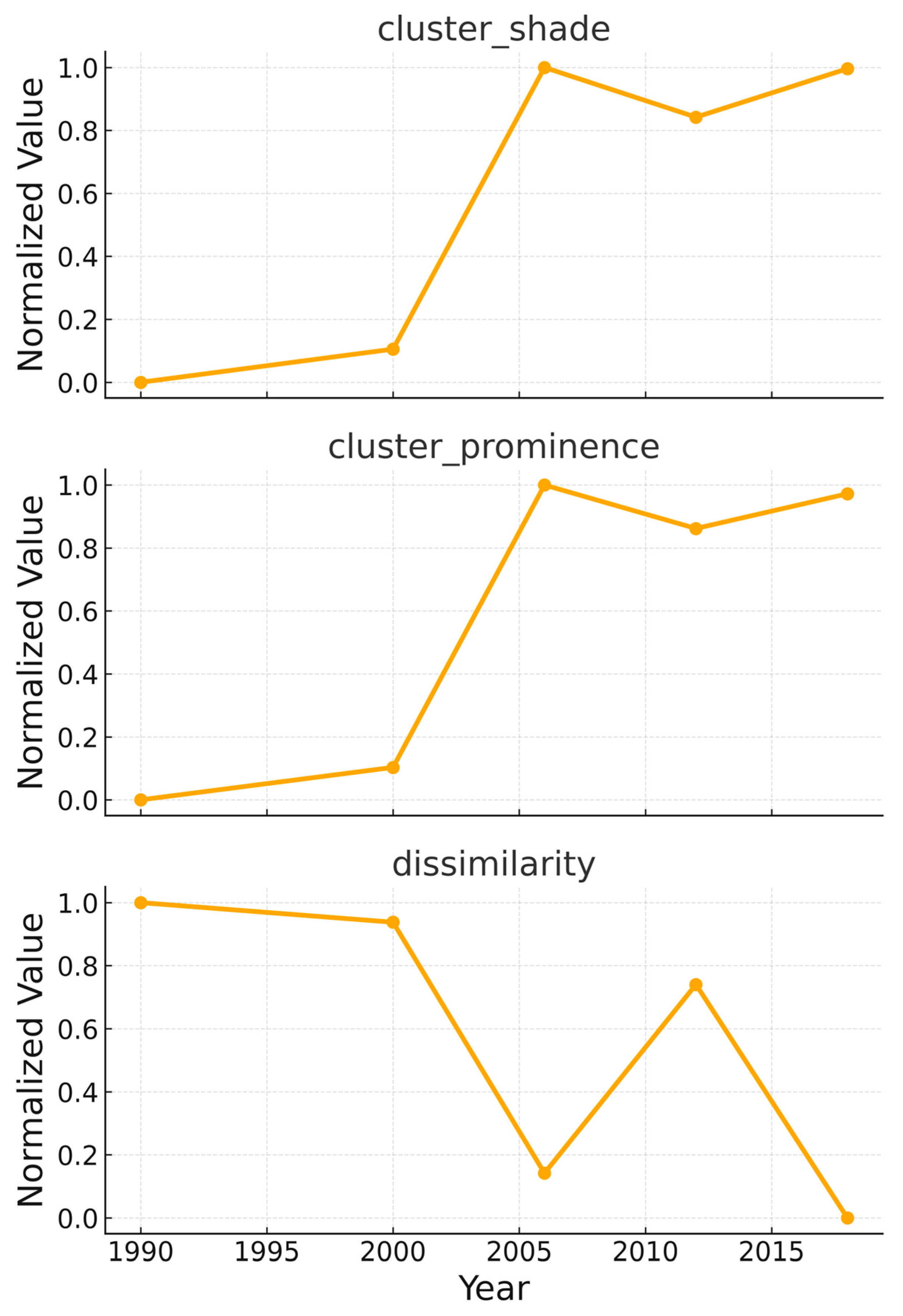

3.1.2. Dynamics of GLCM Texture Measures

3.2. Integrated Reading (FD × GLCM)

3.3. Dynamics of Kolmogorov Complexity and Fractal Measures

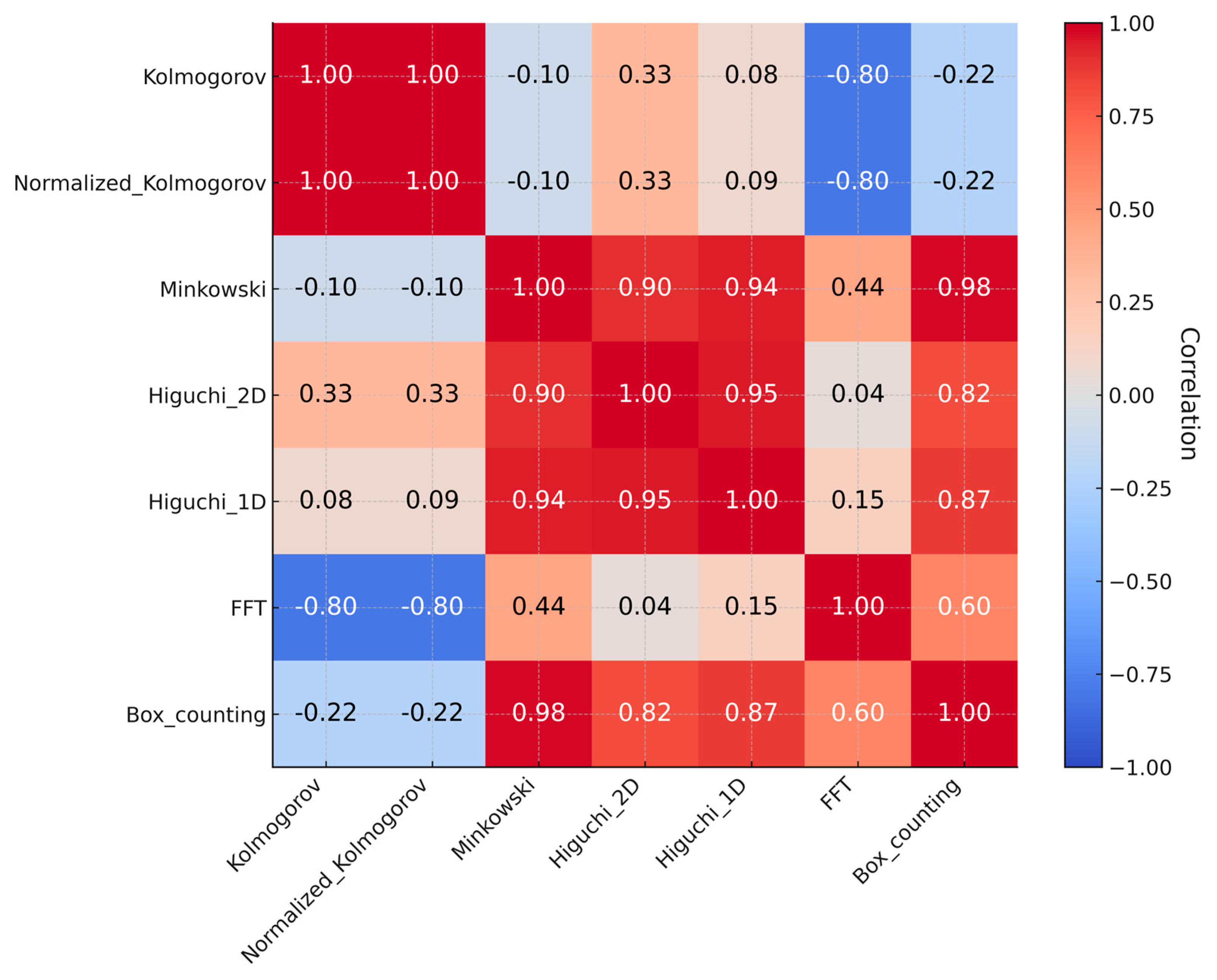

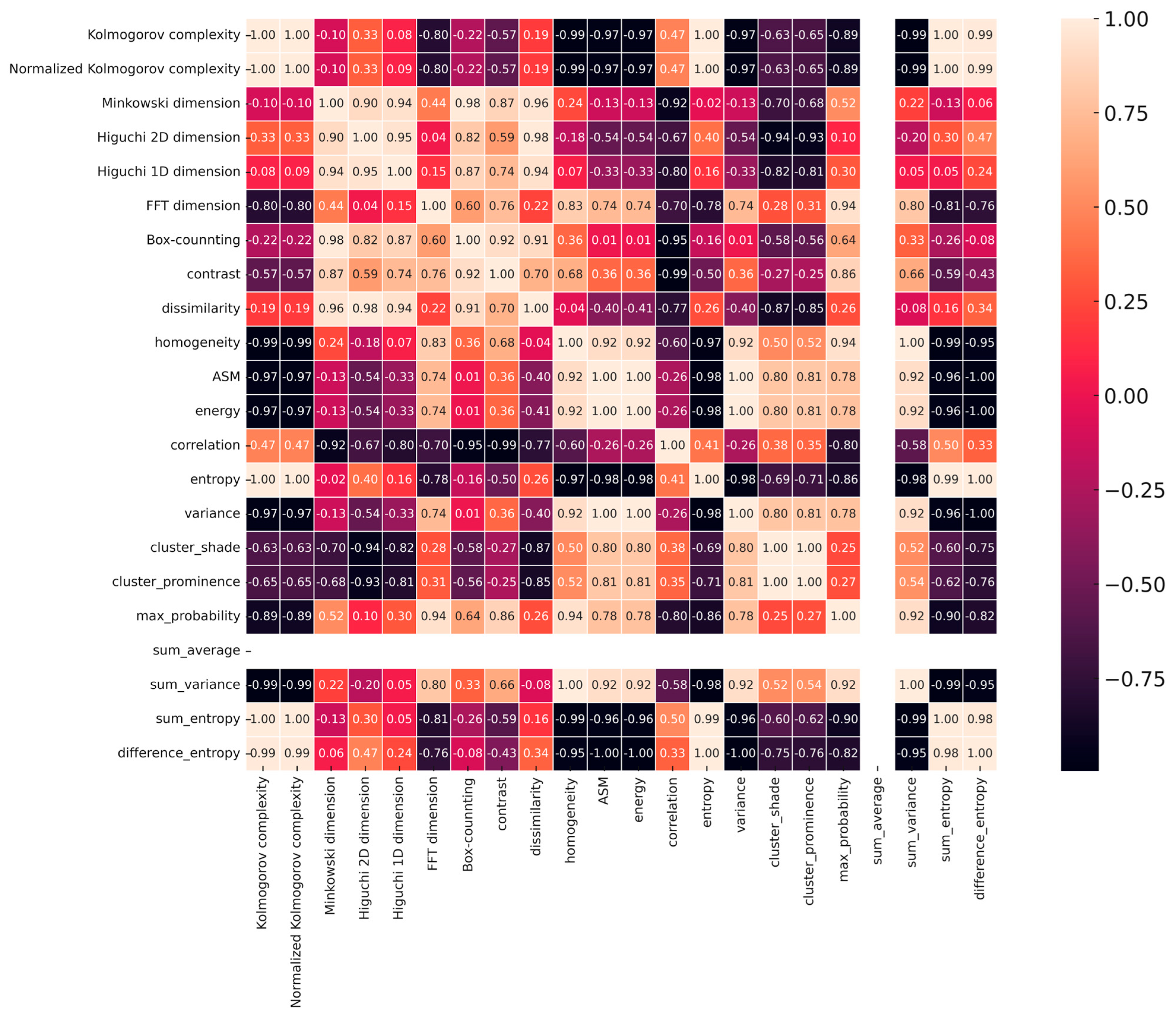

3.4. Relationships Between Complexity and Fractal Measures

3.5. Trends in GLCM Texture Measures

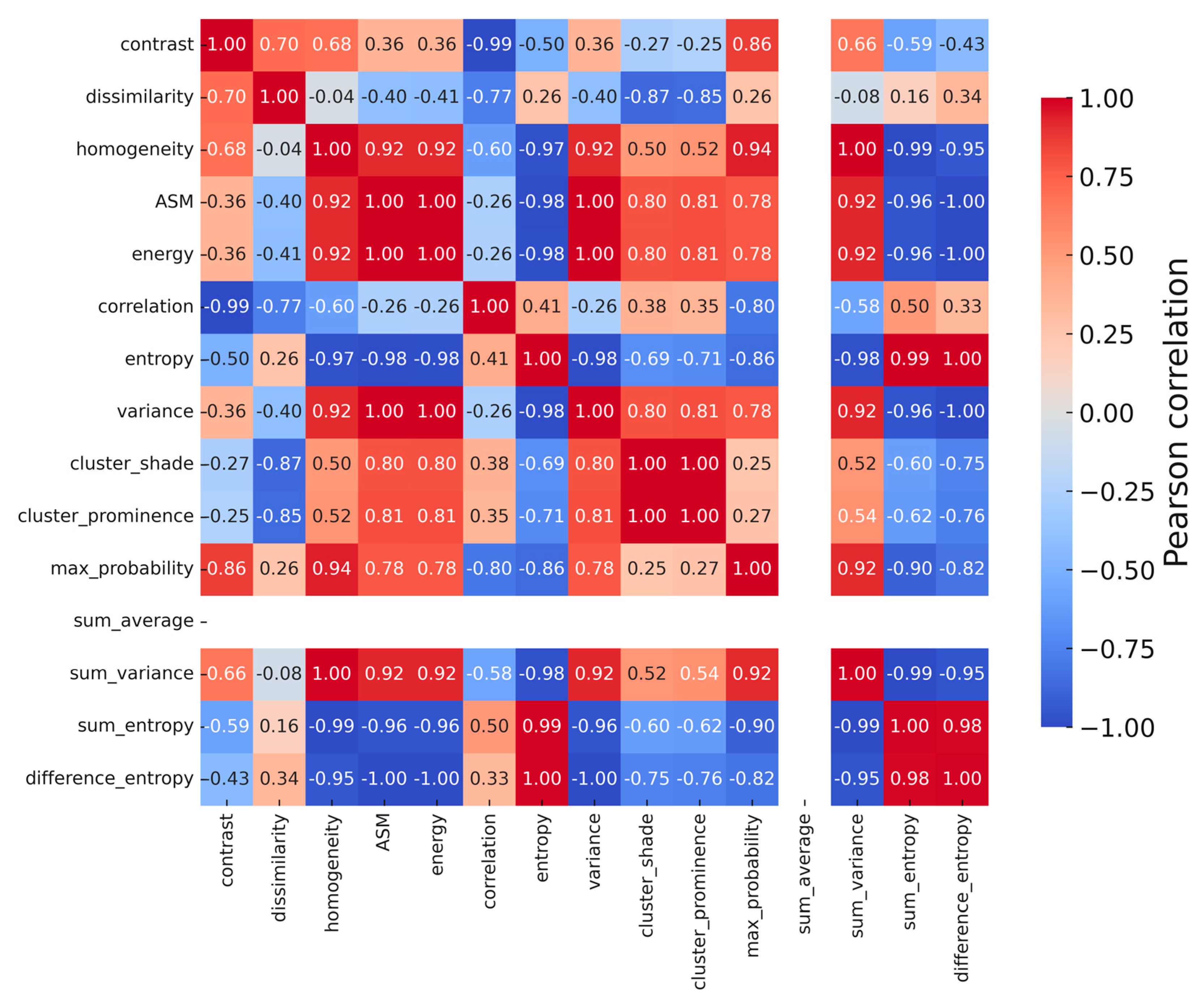

3.6. Correlations Within GLCM Measures

3.7. Interplay Between Fractal, Kolmogorov, and GLCM Measures

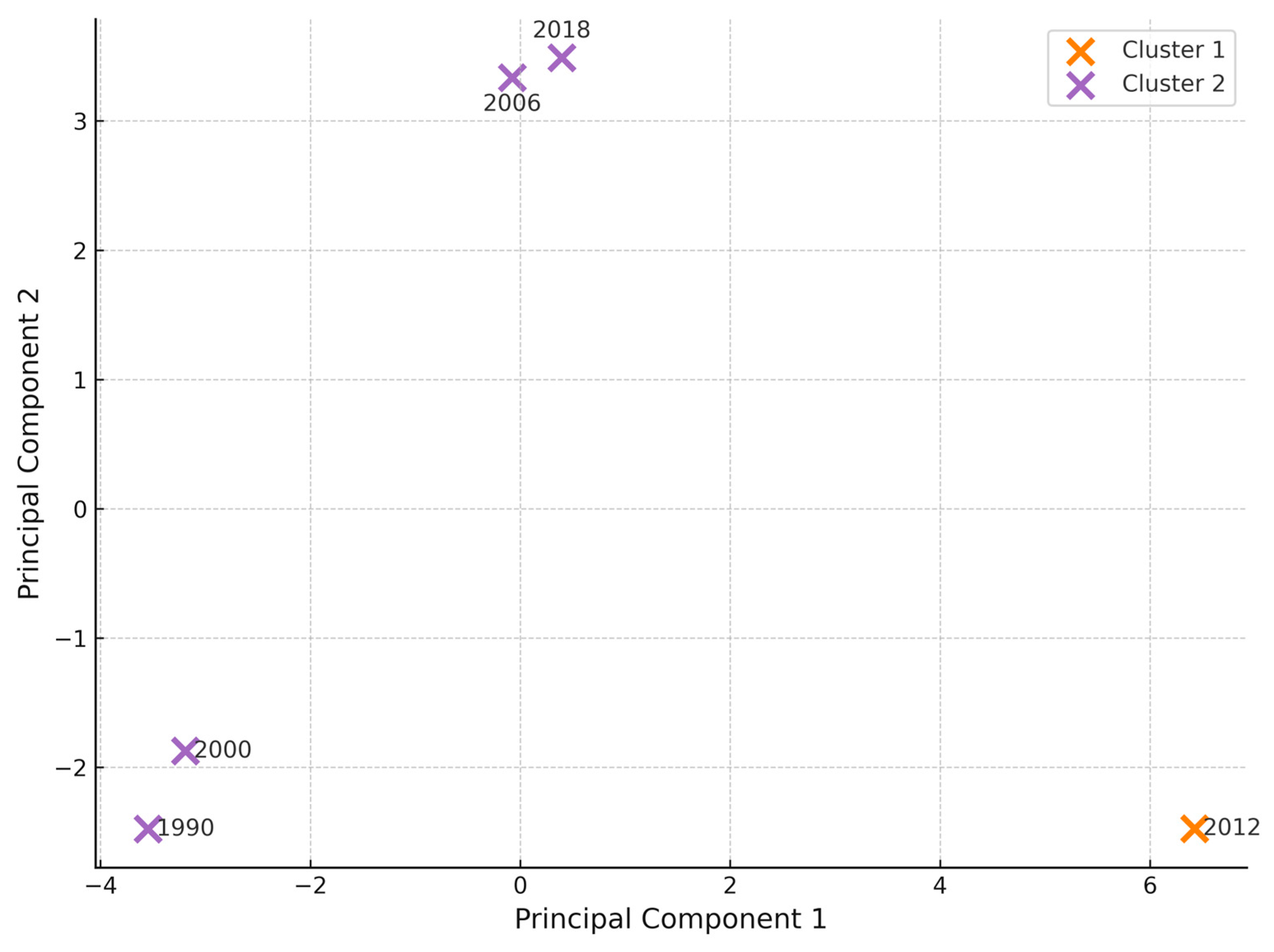

3.8. Dimensionality Reduction via PCA

3.9. Temporal Clustering and Structural Transition

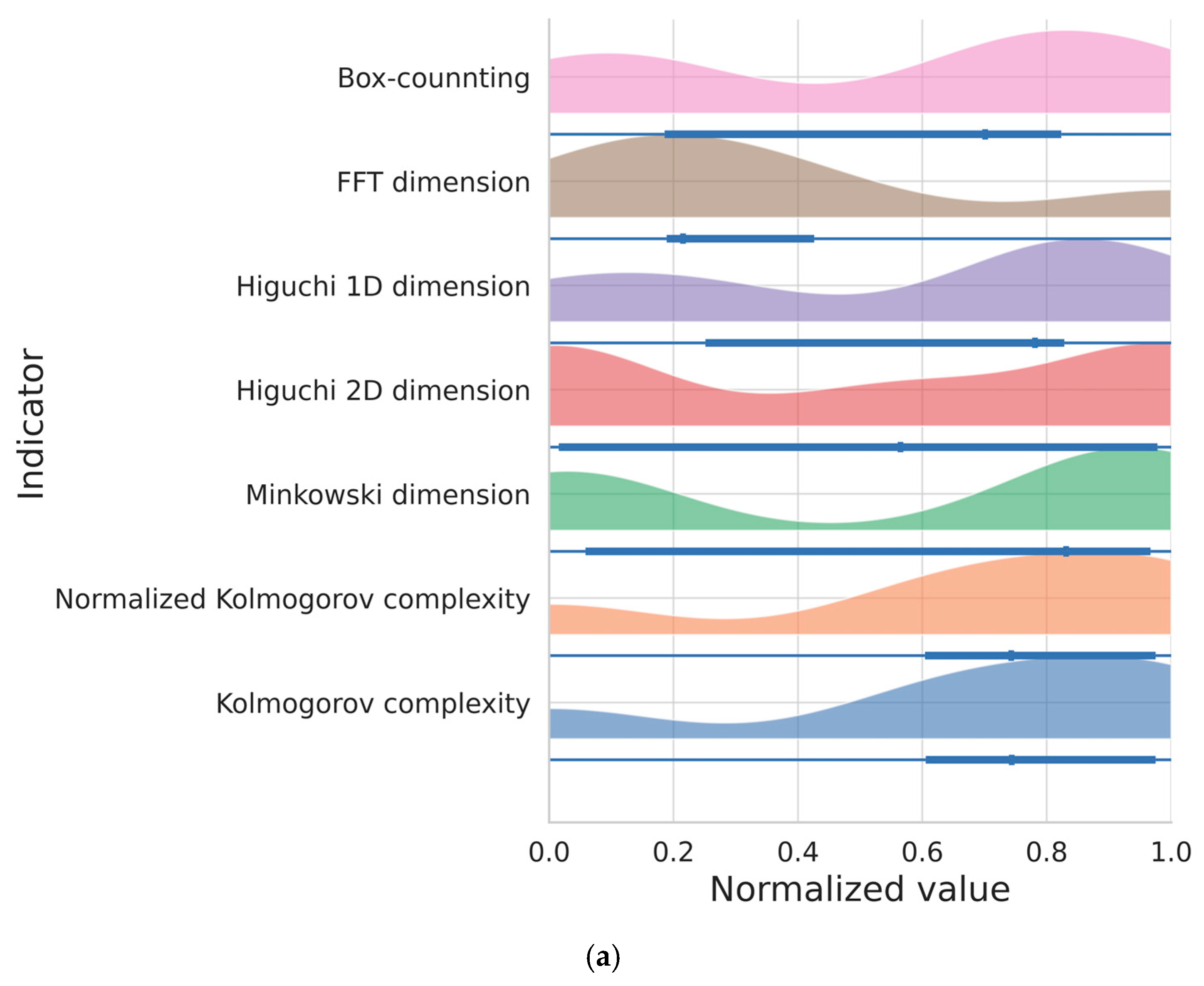

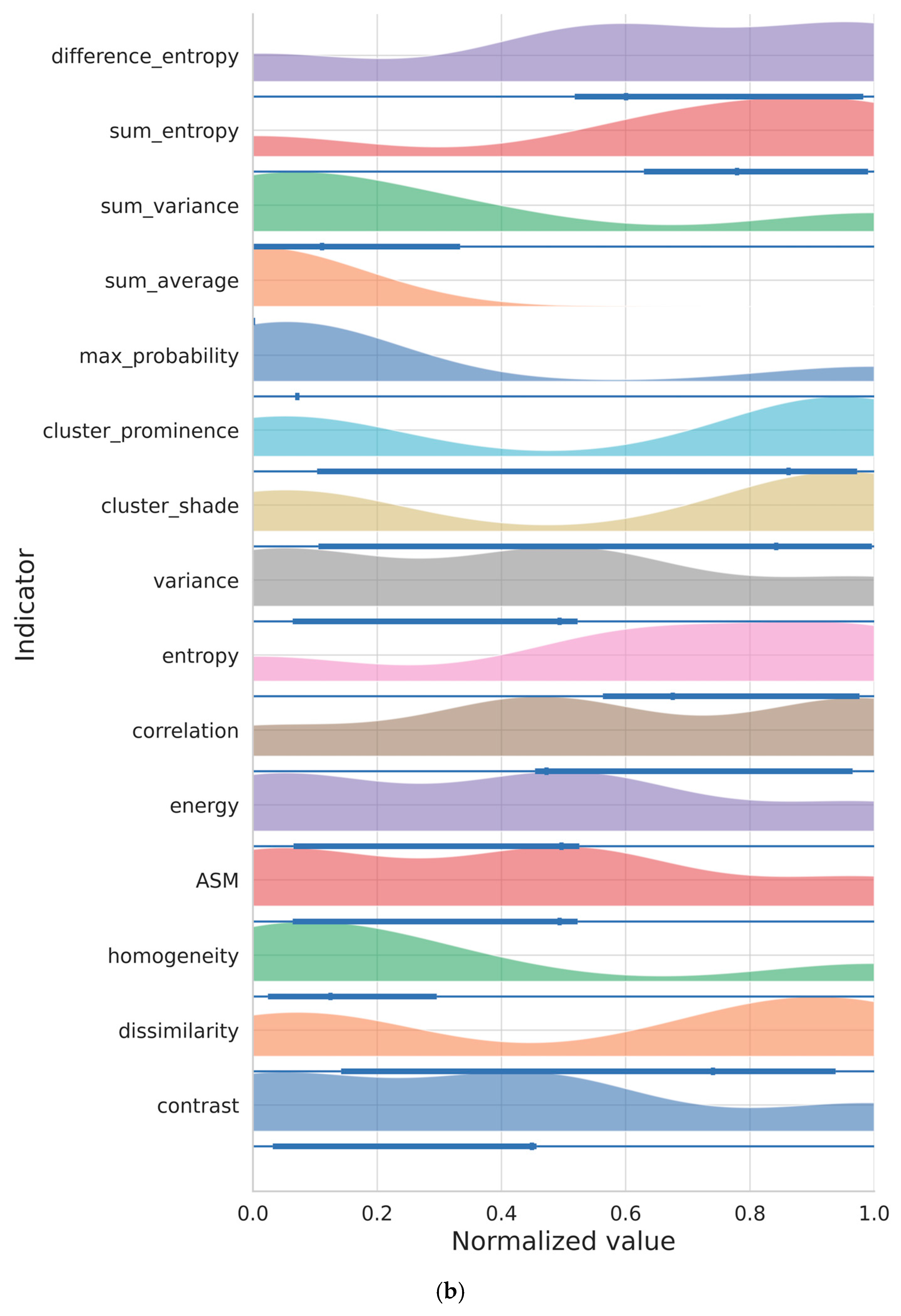

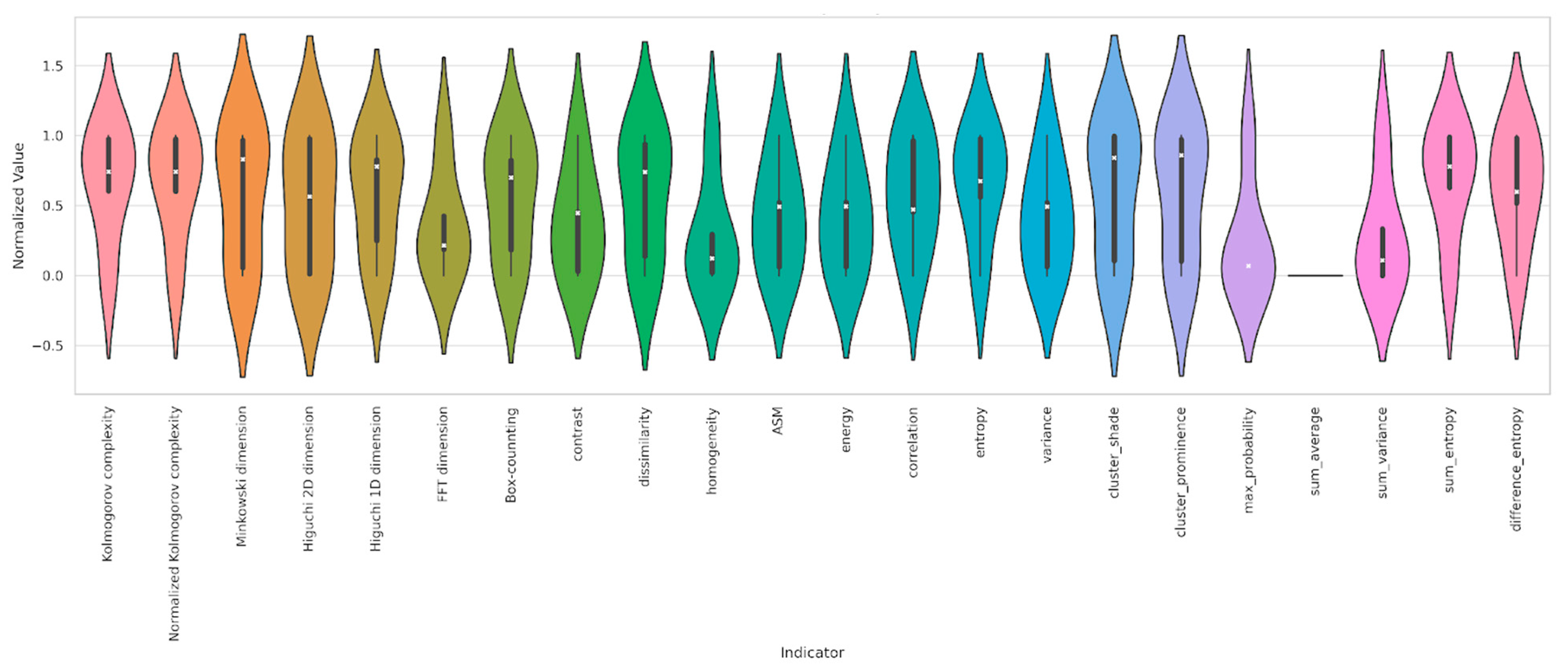

3.10. Distribution Patterns of All Measures

3.11. Summary of Key Measures

- (1)

- Measures such as entropy, dissimilarity, and cluster prominence show long-tailed distributions, reflecting substantial variability across years.

- (2)

- Features like ASM and homogeneity exhibit tightly clustered values, confirming greater temporal consistency.

- (3)

- Fractal and complexity-based measures (e.g., Higuchi 2D, FFT, Kolmogorov complexity, and Normalised KC) present mid-to-high normalised values, consistent with their systemic importance.

- (4)

- The hybrid visualisation format enhances insight by combining density shape (violin), individual values (dots), and summary statistics (box).

3.12. Sensitivity of Complexity Indices to CLC Classification Level

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Insights from Measure Dynamics

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.3. Theoretical Contributions and Novelty

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LULC | Land Use and Land Cover |

| CLC | CORINE Land Cover |

| KC | Kolmogorov Complexity |

| NKC | Normalised Kolmogorov Complexity |

| FD | Fractal Dimension |

| GLCM | Grey-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix |

| ASM | Angular Second Moment |

| IDM | Inverse Difference Moment |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NDVI | Normalised Difference Vegetation Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- FAO. Land Statistics 2001–2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nistor, M.-M.; Nicula, A.S.; Haidu, I.; Surdu, I.; Carebia, I.-A.; Petrea, D. GIS Integration Model of Metropolitan Area Sustainability Index (MASI). The Case of Paris Metropolitan Area. J. Settlements Spat. Plan. 2019, 10, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kumar, V. Assessment of Urban Sprawl, Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Land Consumption Rate in Hisar City, Haryana, India. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Ž.; Boerboom, L.; Glade, T. Future Forest Cover Change Scenarios with Implications for Landslide Risk: An Example from Buzau Subcarpathians, Romania. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cheng, W. Geomorphic Influences on Land Use/Cover Diversity and Pattern. Catena 2023, 230, 107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menakanit, A.; Davivongs, V.; Naka, P.; Pichakum, N. Bangkok’s Urban Sprawl: Land Fragmentation And Changes of Peri-Urban Vegetable Production Areas in Thawi Watthana District. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2022, 14, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.; Fuchs, R.; Rounsevell, M.; Herold, M. Global Land Use Changes Are Four Times Greater than Previously Estimated. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Fischer, G.; Folke, C.; et al. The Causes of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: Moving beyond the Myths. Glob. Environ. Change 2001, 11, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Lambin, E.F.; Reenberg, A. The Emergence of Land Change Science for Global Environmental Change and Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20666–20671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeleye, S.O.; Okhimamhe, A.A.; Sanfo, S.; Fürst, C. Impacts of Land Use and Land Cover Changes on Migration and Food Security of North Central Region, Nigeria. Land 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Erb, K.; Meyfroidt, P.; Müller, D.; Verburg, P.H.; Estel, S.; Haberl, H.; Hostert, P.; Jepsen, M.R.; Kastner, T.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Mapping Land Use Intensity Globally. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtt, G.C.; Chini, L.; Sahajpal, R.; Frolking, S.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Calvin, K.; Doelman, J.C.; Fisk, J.; Fujimori, S.; Klein Goldewijk, K.; et al. Harmonization of Global Land Use Change and Management for the Period 850–2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 5425–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoglu, E.; Williams, B. Determinants of Urban Expansion and Agricultural Land Conversion in 25 EU Countries. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Land Take and Land Degradation in Functional Urban Areas; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. EEA Environmental Statement 2021; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Draux, H.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Bürgi, M.; Kizos, T.; Kuemmerle, T.; Primdahl, J.; Verburg, P.H. The Driving Forces of Landscape Change in Europe: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayet, C.M.J.; Verburg, P.H. Modelling Opportunities of Potential European Abandoned Farmland to Contribute to Environmental Policy Targets. Catena 2023, 232, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbrechts, L.; Azevedo, J.C.; Verburg, P. Trajectories and Drivers Signalling the End of Agricultural Abandonment in Trás-Os-Montes, Portugal. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rusu, M. Land Use Change in Southern Romania after the Collapse of Socialism. Reg. Environ. Change 2009, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Rusu, M.; Griffiths, P. Lost in Transition: Determinants of Post-Socialist Cropland Abandonment in Romania. J. Land Use Sci. 2009, 4, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taff, G.N.; Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Ozdeneral, E.; Walsh, S.J. Reforestation in Central and Eastern Europe After the Breakdown of Socialism. In Reforesting Landscapes; Nagendra, H., Southworth, J., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 10, pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, I.; Mitrică, B.; Kucsicsa, G.; Popovici, E.-A.; Dumitraşcu, M.; Cuculici, R. Post-Communist Land Use Changes Related to Urban Sprawl in the Romanian Metropolitan Areas. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 6, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Petrişor, L.E. Recent Land Cover and Use in Romania: A Conservation Perspective. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.M.; Nicula, A.S.; Cervi, F.; Man, T.C.; Irimuş, I.A.; Surdu, I. Groundwater Vulnerability GIS Models in the Carpathian Mountains Under Climate and Land Cover Changes. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018, 16, 5095–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S.M.; Mititelu-Ionuș, O.; Ștefănescu, D.M. Linking Land Use and Land Cover Changes and Ecosystem Services’ Potential in Natura 2000 Site “Nordul Gorjului de Vest” (Southwest Romania). Land 2024, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, F. The Algorithmic Complexity of Landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobotaru, A.-M.; Andronache, I.; Ahammer, H.; Jelinek, H.F.; Radulovic, M.; Pintilii, R.-D.; Peptenatu, D.; Drăghici, C.-C.; Simion, A.-G.; Papuc, R.-M.; et al. Recent Deforestation Pattern Changes (2000–2017) in the Central Carpathians: A Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix and Fractal Analysis Approach. Forests 2019, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Guldmann, J.-M. Measuring Continuous Landscape Patterns with Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM) Indices: An Alternative to Patch Metrics? Ecol. Indic. 2020, 109, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ogawa, S. Fractal Analysis Of Colors And Shapes For Natural And Urbanscapes URBANSCAPES. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, XL-7/W3, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronache, I. Application of Fractal Analysis in Interpreting 2D and 3D Grayscale Images: Methodologies and Case Studies. J. Bulg. Geogr. Soc. 2025, 52, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, A.G.; Andronache, I.; Ahammer, H.; Marin, M.; Loghin, V.; Nedelcu, I.D.; Popa, C.M.; Peptenatu, D.; Jelinek, H.F. Particularities of Forest Dynamics Using Higuchi Dimension. Parâng Mountains as a Case Study. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobotaru, A.-M.; Andronache, I.; Ahammer, H.; Radulovic, M.; Peptenatu, D.; Pintilii, R.-D.; Drăghici, C.-C.; Marin, M.; Carboni, D.; Mariotti, G.; et al. Application of Fractal and Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix Indices to Assess the Forest Dynamics in the Curvature Carpathians—Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujoiu-Mare, M.-R.; Mihai, B.-A. Mapping Land Cover Using Remote Sensing Data and GIS Techniques: A Case Study of Prahova Subcarpathians. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 32, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenil, H. A Review of Methods for Estimating Algorithmic Complexity: Options, Challenges, and New Directions. Entropy 2020, 22, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peptenatu, D.; Andronache, I.; Ahammer, H.; Taylor, R.; Liritzis, I.; Radulovic, M.; Ciobanu, B.; Burcea, M.; Perc, M.; Pham, T.D.; et al. Kolmogorov Compression Complexity May Differentiate Different Schools of Orthodox Iconography. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, K.J. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, N.; Chaudhuri, B.B. An Efficient Differential Box-Counting Approach to Compute Fractal Dimension of Image. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1994, 24, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.C.; Ong, S.H. Jayasooriah a Practical Method for Estimating Fractal Dimension. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 1995, 16, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, E.; Pancorbo, M.; Aguilar, M. Fractal Characterization by Frequency Analysis. I. Surfaces. J. Microsc. 1993, 172, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. Approach to an Irregular Time Series on the Basis of the Fractal Theory. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1988, 31, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammer, H. Higuchi Dimension of Digital Images. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammer, H.; Sabathiel, N.; Reiss, M.A. Is a Two-Dimensional Generalization of the Higuchi Algorithm Really Necessary? Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2015, 25, 073104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasić, S. On 2D Generalization of Higuchi’s Fractal Dimension. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2014, 69, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuc, B.; Zucker, S.W.; Tricot, C.; Quiniou, J.F.; Wehbi, D. Evaluating the Fractal Dimension of Surfaces. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1989, 425, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, SMC-3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammer, H.; Reiss, M.A.; Hackhofer, M.; Andronache, I.; Radulovic, M.; Labra-Spröhnle, F.; Jelinek, H.F. ComsystanJ: A Collection of Fiji/ImageJ2 Plugins for Nonlinear and Complexity Analysis in 1D, 2D and 3D. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianăș, A.-N.; Ivan, R. Post-Communist Land Cover and Use Changes in Romanian Banat, Based on Corine Land Cover Data. Rev. Hist. Geogr. Toponomast. 2022, XVII, 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Niță, A.; Mazilu, M.; Curcan, G. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Trends of Major Agricultural Crops in Romania Using Interactive Geographic Information System Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liang, D.; Lu, N. Landscape Ecology: Coupling of Pattern, Process, and Scale. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbarth, M.H.K.; Nowosad, J.; De Flamingh, A.; Simpkins, C.E.; Jung, M.; Gerber, G.; Bosch, M. Computational Methods in Landscape Ecology. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2024, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupidura, P. The Comparison of Different Methods of Texture Analysis for Their Efficacy for Land Use Classification in Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanmiri, F.; Parker, D.C. An Overview of Fractal Geometry Applied to Urban Planning. Land 2022, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, A. Fractal Analysis of the Urbanization at the Outskirts of the City: Models, Measurement and Explanation. Cybergeo 2007, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhen, W.; Luo, B.; Shi, D.; Li, Z. Analyzing Spatial–Temporal Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of Landscape Changes in the Context of Comprehensive Urban Expansion Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Longley, P.A. Fractal Cities: A Geometry of Form and Function; Academic Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.G.; Gardner, R.H. Landscape Metrics. In Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 97–142. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini, R.; Bueno, A.D.A.; Gardner, T.A.; Prado, P.I.; Metzger, J.P. Beyond the Fragmentation Threshold Hypothesis: Regime Shifts in Biodiversity Across Fragmented Landscapes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, W.L.; Netzband, M. Assessment of ASTER Land Cover and MODIS NDVI Data at Multiple Scales for Ecological Characterization of an Arid Urban Center. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 99, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Hostert, P. Agricultural Land Change in the Carpathian Ecoregion after the Breakdown of Socialism and Expansion of the European Union. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 045024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Venter, Z.; Demuzere, M.; Zhan, W.; Gao, J.; Zhao, L.; Qian, Y. Large disagreements in estimates of urban land across scales and their implications. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodchild, M.F. How Well Do We Really Know the World? Uncertainty in GIScience. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 20, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | %Δ (2018 vs. 1990) | 95% CI (Bootstrap) |

|---|---|---|

| Kolmogorov complexity | −4.258 | [−14.244%, −0.265%] |

| Normalised Kolmogorov complexity | −4.26 | [−14.214%, −0.155%] |

| Minkowski dimension | −0.373 | [−0.640%, 0.064%] |

| Higuchi 2D dimension | −0.364 | [−0.626%, −0.105%] |

| Higuchi 1D dimension | −0.375 | [−0.719%, 0.080%] |

| FFT dimension | −0.374 | [−1.443%, 2.157%] |

| Box-counting | −0.144 | [−0.243%, 0.046%] |

| Measure | %Δ (2018 vs. 1990) | 95% CI (Bootstrap) |

|---|---|---|

| contrast | −7.943 | [−17.513%, 15.902%] |

| dissimilarity | −5.279 | [−8.290%, −1.209%] |

| homogeneity | 1.086 | [−0.632%, 4.927%] |

| ASM | 2.164 | [0.825%, 5.578%] |

| energy | 1.077 | [0.428%, 2.820%] |

| correlation | 0.257 | [−0.337%, 0.584%] |

| entropy | −3.292 | [−10.089%, −0.722%] |

| variance | 2.165 | [0.794%, 5.717%] |

| cluster_shade | 3.22 | [1.808%, 5.407%] |

| cluster_prominence | 3.804 | [2.111%, 6.545%] |

| max_probability | −0.003 | [−0.023%, 0.044%] |

| sum_average | 0.0 | [0.000%, 0.000%] |

| sum_variance | 2.727 | [−0.761%, 12.260%] |

| sum_entropy | −3.617 | [−12.890%, 0.368%] |

| difference_entropy | −2.545 | [−7.062%, −0.706%] |

| Domain | Most Informative measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Fractal/KC | Minkowski, Higuchi 2D, Box-counting | Capture, geometric and curve-based complexity |

| GLCM Texture | Cluster shade, Cluster prominence, Dissimilarity | Highlight asymmetry and textural irregularity |

| Cross-Domain PCA | PC1: entropy/fractals; PC2: ASM/homogeneity | Structural simplification vs. richness |

| Temporal Clustering | 2 stable clusters (pre-/post-2006) | Landscape transition confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andronache, I.; Ciobotaru, A.-M. Structural Change in Romanian Land Use and Land Cover (1990–2018): A Multi-Index Analysis Integrating Kolmogorov Complexity, Fractal Analysis, and GLCM Texture Measures. Geomatics 2025, 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040078

Andronache I, Ciobotaru A-M. Structural Change in Romanian Land Use and Land Cover (1990–2018): A Multi-Index Analysis Integrating Kolmogorov Complexity, Fractal Analysis, and GLCM Texture Measures. Geomatics. 2025; 5(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040078

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndronache, Ion, and Ana-Maria Ciobotaru. 2025. "Structural Change in Romanian Land Use and Land Cover (1990–2018): A Multi-Index Analysis Integrating Kolmogorov Complexity, Fractal Analysis, and GLCM Texture Measures" Geomatics 5, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040078

APA StyleAndronache, I., & Ciobotaru, A.-M. (2025). Structural Change in Romanian Land Use and Land Cover (1990–2018): A Multi-Index Analysis Integrating Kolmogorov Complexity, Fractal Analysis, and GLCM Texture Measures. Geomatics, 5(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040078