Supporting Disabilities Using Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things: Research Issues and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Among the six selected disability categories (i.e., Down Syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Mobility Impairment, Hearing Impairment, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Visual Impairment), which ones are most frequently targeted in AI and IoT research prototypes published between 2020 and 2024?

- RQ2: Which monitoring, analysis, and assistance technologies, models, and data modalities are most commonly adopted, and in which operational settings?

- RQ3: To what extent do the reviewed prototypes address or offer support for security, privacy, personalization, cost-efficiency, and response time?

- RQ4: What are the cross-cutting gaps and directions in the AI–IoT assistive technology landscape?

- The survey describes the application of AI and IoT for assistive technologies with regard to facilitating accessibility, communication, and independence for different types of disabilities, including Down Syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Mobility Impairment, Hearing Impairment, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Visual Impairment.

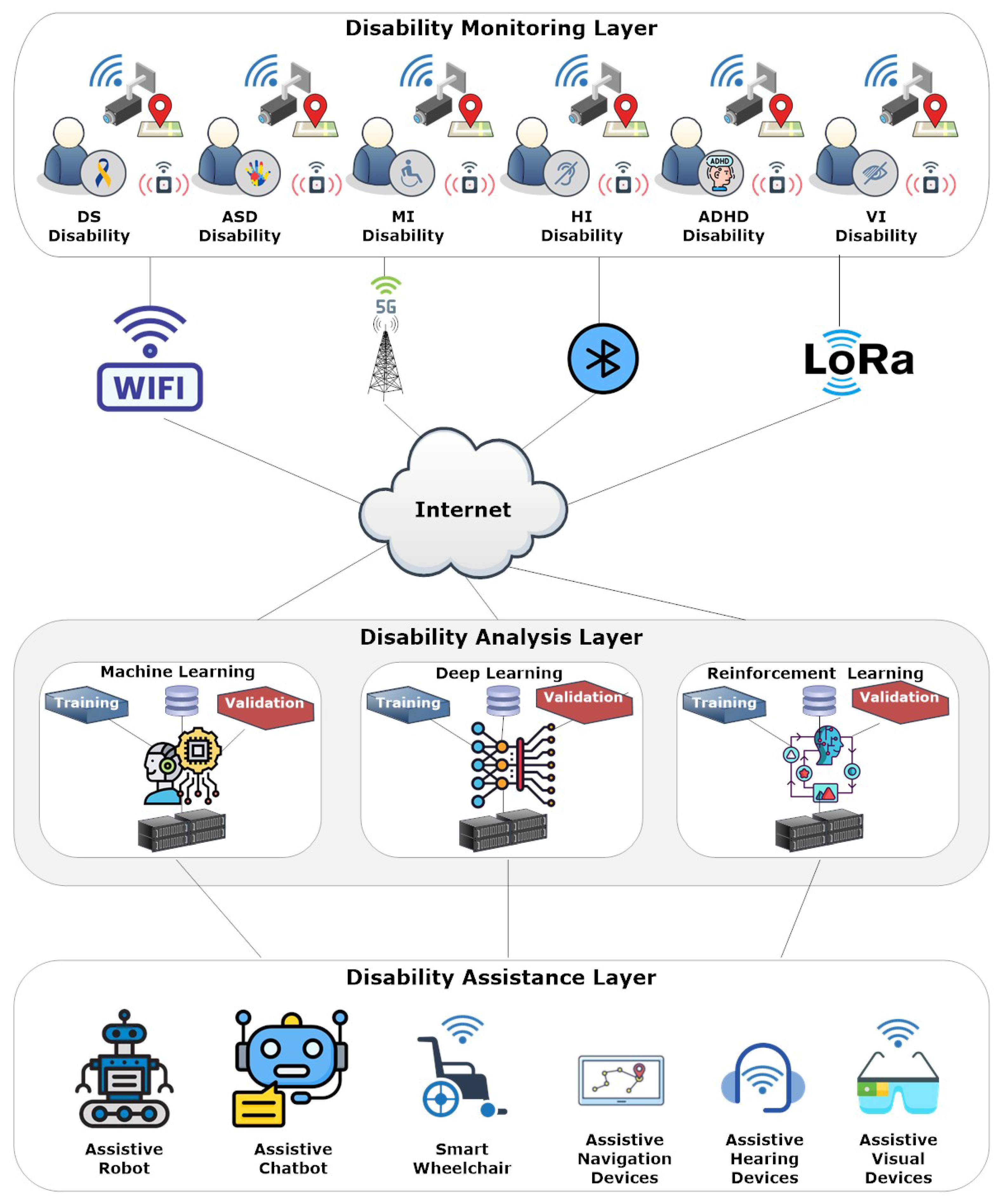

- An analytical framework is proposed for evaluating AI and IoT disability assistance prototypes. The framework consists of three different layers: the Disability Monitoring, Disability Analysis, and Disability Assistance layers. In each layer, a set of dimensions are identified (e.g., technology, data, security, customization, and response time) and used as criteria to evaluate the research prototypes.

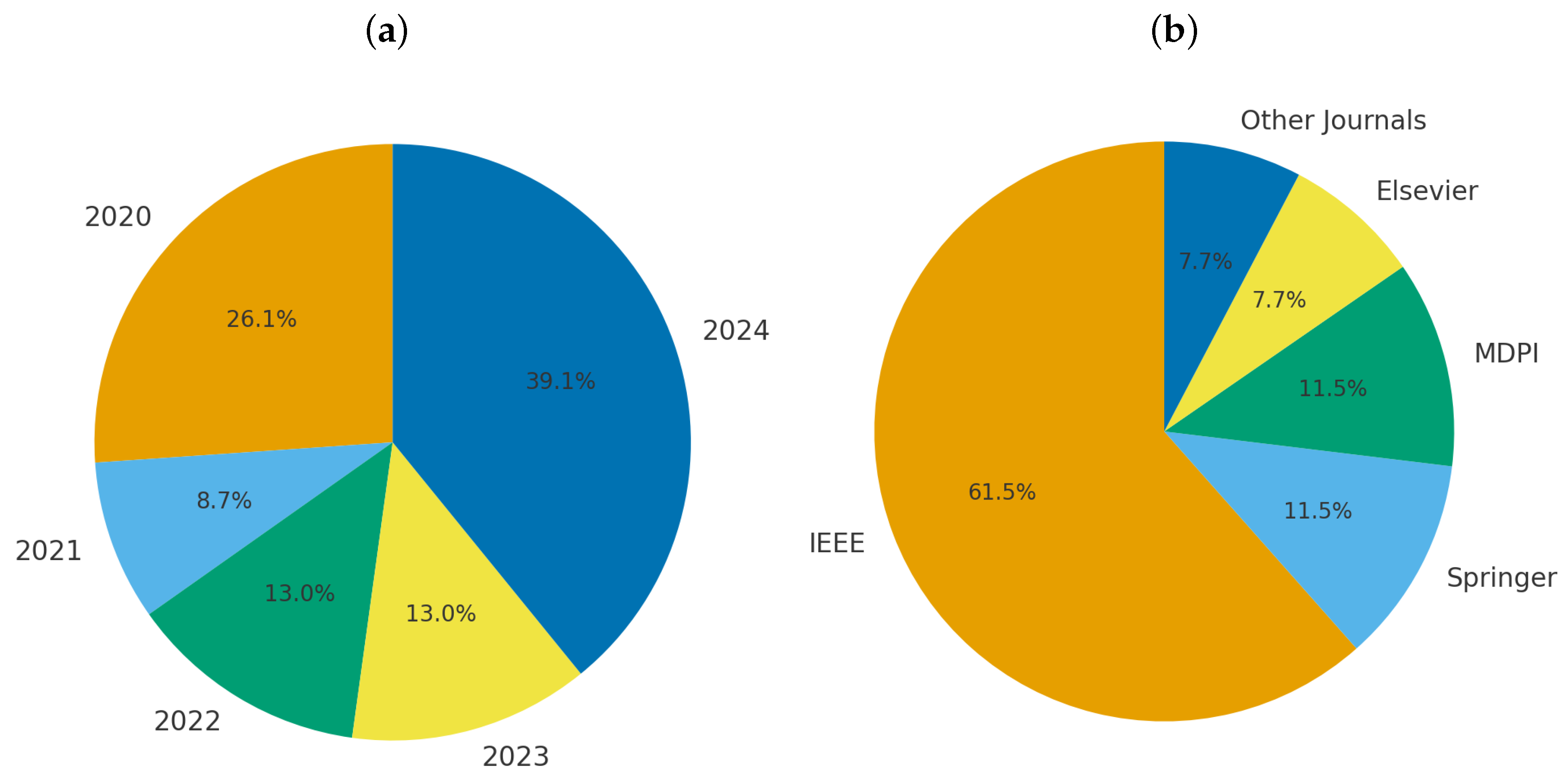

- The survey evaluates 30 AI and IoT disability assistance research prototypes published from 2020 to 2024 that demonstrate the latest trends in the field. The evaluation offers valuable insights into the new strategies, technologies, and approaches that will define future AI- and IoT-based disability support.

- The survey identifies significant research issues in AI and IoT-assisted technology (e.g., security, scalability, cost-effectiveness, and user-centric design) and explores research directions to address them.

2. Background

2.1. Assistive Technologies and Disability

2.2. Internet of Things (IoT)

2.3. Human–Computer Interaction (HCI)

2.4. Machine Learning (ML)

2.5. Deep Learning (DL)

3. Related Work

4. AI and IoT Disability Assistance Analytical Framework

4.1. Layers of the AI and IoT Disability Assistance Analytical Framework

4.2. Criteria for Evaluating Assistive Disability

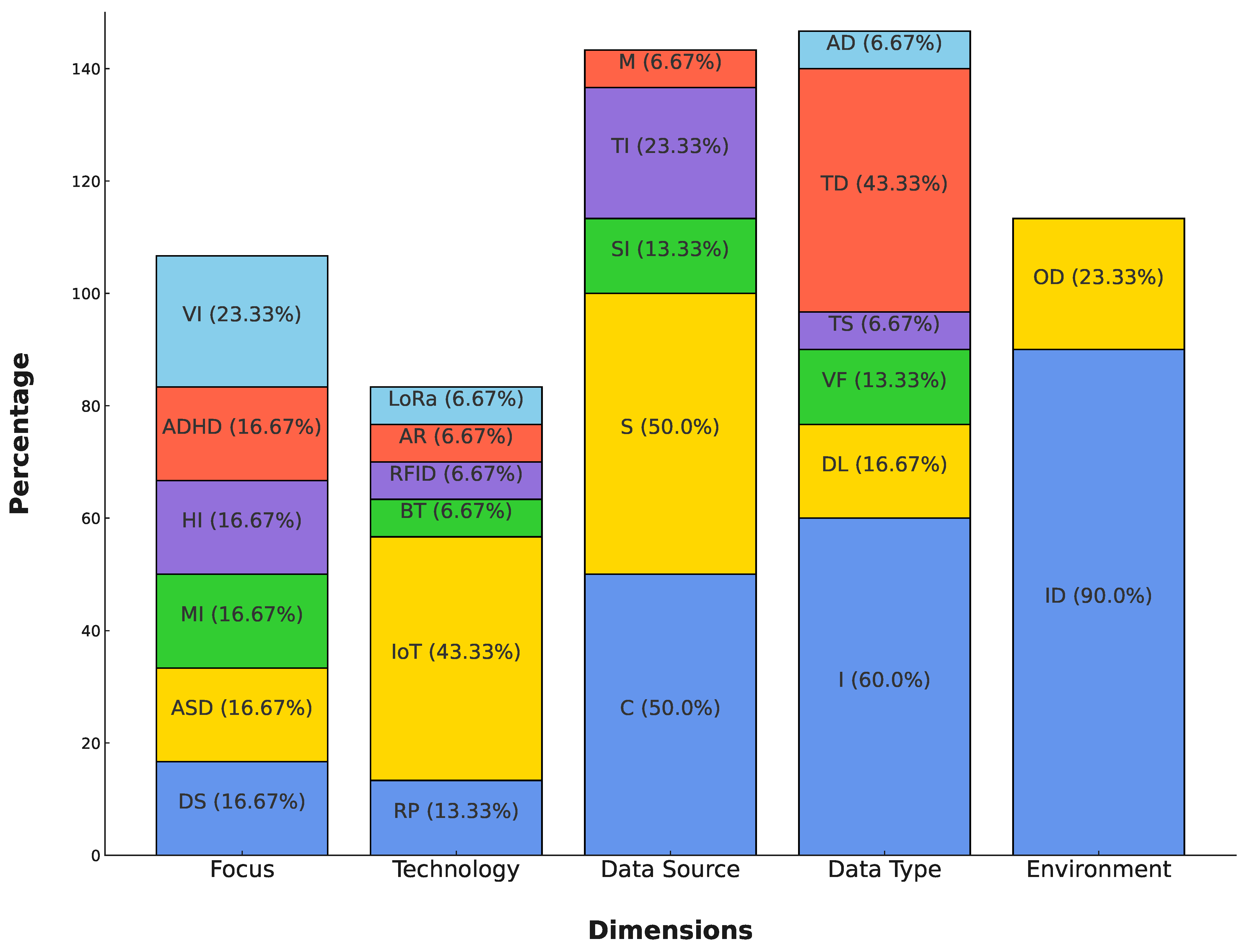

4.2.1. Disability Monitoring Layer

- Down Syndrome (DS): Down Syndrome prototypes collect image data (i.e., often from placed cameras) for real-time monitoring, behavioral profiling, or other diagnostic purposes.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Sensors (i.e., loop detectors, radar, microwave, etc.) are installed in spaces to gather activity and movement data in real time.

- Mobility Impairment (MI): Global Positioning System (GPS) or navigational devices are used to track movement patterns, travel distances, and travel times.

- Hearing Impairment (HI): Mobile devices and other interfaces collect text and audio information for real-time support and data analysis.

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Information is extracted from the user interface app or intelligent systems to analyze behavioral dynamics and adaptively support.

- Visual Impairment (VI): Advanced imaging technologies and weather information boost compass reading and situational awareness.

- Internet of Things (IoT): A general-purpose device used on embedded hardware that can collect and share real-time data with disabilities like Autism Spectrum Disorder, Mobility Impairment, or Hearing Impairment.

- Raspberry Pi (RP): Small stand-alone devices, primarily for Down Syndrome and Visual Impairment applications.

- Arduino (AR): Sensors used in Mobility Impairment-related projects for integration and real-time data monitoring.

- Bluetooth (BT): A communication medium that allows data to be sent and received from one device to another, mostly used in Autism Spectrum Disorder systems.

- Long-Range Communication (LoRa): A communication medium effective for Mobility Impairment and Visual Impairment to give access to a wide area.

- Radio Frequency Identification (RFID): Sensors for Autism Spectrum Disorder or Mobility Impairment to track and recognize where people are.

- Cameras (C): These gather visual information for analyzing, like obstacles or behavior.

- Sensors (S): These collect environmental and activity information for trends or anomalies.

- Scanned Images (SI): These take static visuals using medical devices (e.g., Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)) for deeper analysis, especially in Autism Spectrum Disorder or Mobility Impairment environments.

- Text Inputs (TI): These provide user-specific inputs in the form of text or a command.

- Microphones (M): These capture audio data for Hearing Impairment applications.

- Images (I): Images from cameras for recognition of patterns or detection of objects.

- People with Disabilities Location Data (DL): This denotes geographical locations mostly for Mobility Impairment and Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- Video Frames (VF): These return sorted image data (i.e., image frames) for dynamic analysis, mostly in Mobility Impairment and Visual Impairment systems.

- Time-Series Data (TS): This represents trends over time and is very helpful when looking for patterns, especially in Autism Spectrum Disorder or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder prototypes.

- Text Data (TD): This represents written content related to people with disabilities’ activity or symptoms, commonly used in Hearing Impairment and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder applications.

- Audio Data (AD): This denotes audio data that comes from speakers mainly used for Hearing Impairment and Visual Impairment.

- Indoor (ID): Systems cover a safe space like a home, clinic, or school.

- Outdoor (OD): This is for outdoor systems that cover open areas such as parks, streets, or public places.

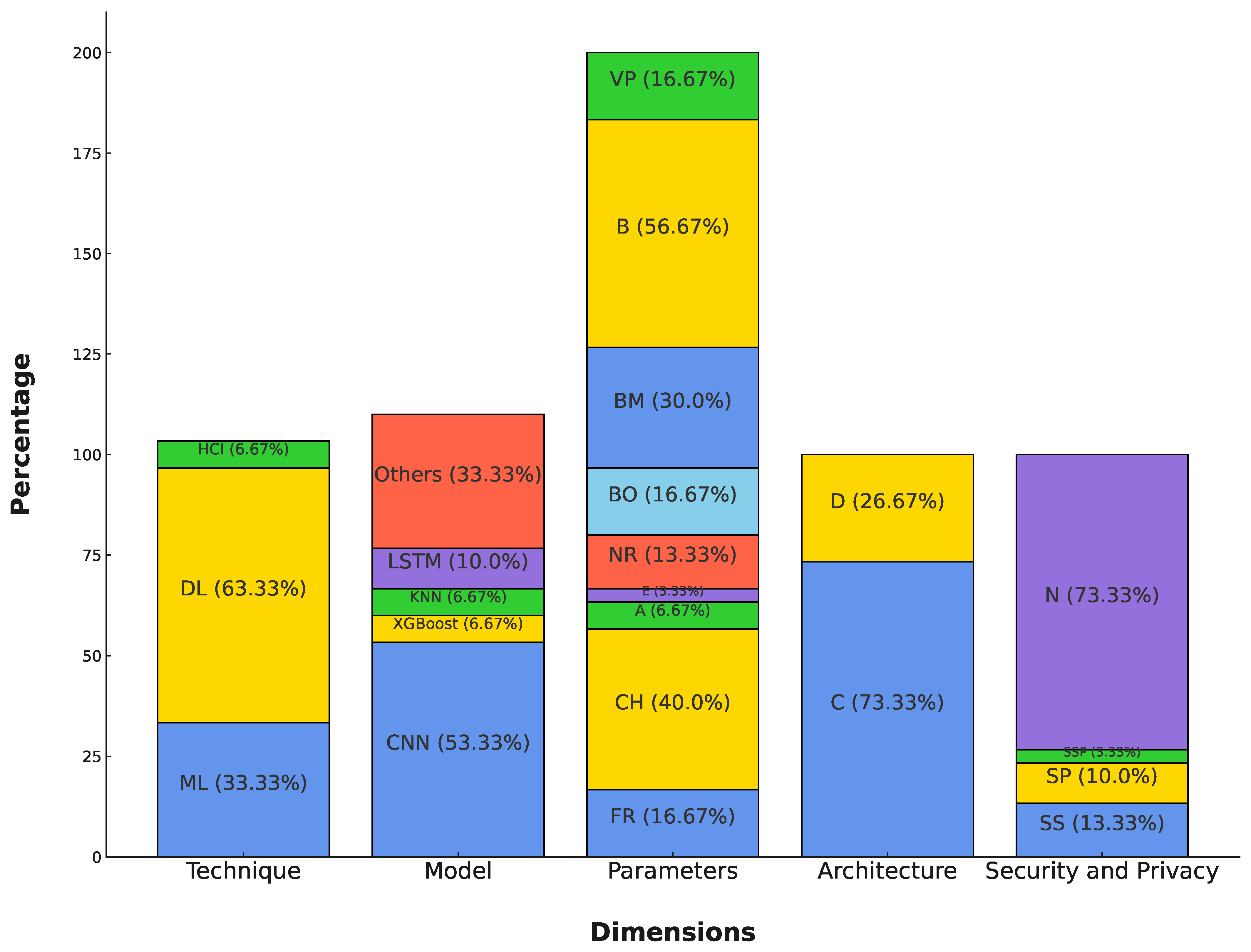

4.2.2. Disability Analysis Layer

- Machine Learning (ML): ML recognizes patterns and predicts and classifies disabilities like Down Syndrome, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Hearing Impairment.

- Deep Learning (DL): This is useful for more challenging data such as images, video frames, and sequences in Autism Spectrum Disorder, Visual Impairment, and Hearing Impairment prototypes.

- Human–Computer Interaction (HCI): This develops interactive systems for those with disabilities such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Hearing Impairment that are user-friendly and accessible.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): This is useful for classification, most often used in Down Syndrome analysis.

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): This has been proven for Autism Spectrum Disorder, Visual Impairment, and Hearing Impairment image and video analysis.

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): High level of predictive power, especially in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Down Syndrome.

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN): This is useful for classification, most often used in Mobility Impairment analysis.

- K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN): A simple classification algorithm to perform MI or Hearing Impairment analysis.

- You Only Look Once (YOLO): This has a proven higher level of object detection commonly used in Visual Impairment or Mobility Impairment detection tasks.

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): This handles linear data like behavioral analysis or visual perception tasks.

- Decision Tree (DT): Simple classification algorithm mostly used in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder analysis.

- Knowledge Model (KM): A model useful for prediction, most often used in Mobility Impairment analysis.

- Random Forest (RF): A model useful for classification, most often used in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder analysis.

- Facial Recognition (FR): Commonly used in Down Syndrome for facial features recognition.

- Children (CH): Limited to children features or attributes mostly used in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Down Syndrome prototypes.

- Adults/Elderly (A/E): Limited to adults or elderly features or attributes mostly used in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Mobility Impairment prototypes.

- Navigation Routes (NR): Plans a route and creates access for people with disabilities, particularly used in Visual Impairment and Mobility Impairment.

- Body Organs (BO): This examines the body’s inner organs for predictive or diagnostic tasks, primarily used in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, or Down Syndrome.

- Drawing (DR): Examines drawing patterns for people with disabilities, mainly used for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- Body Motors (BM): This examines body mechanics, especially in Mobility Impairment and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

- Behavior (B): This observes and monitors behavior, in particular in systems associated with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

- Visual Perception (VP): Query vision-based data for Visual Impairment and Hearing Impairment use cases.

- Centralized (C): Data is centralized in terms of pattern recognition, anomaly or object detection, and predictive analysis. The centralized architecture is easier to manage, requires high computational resources, and is the most common architecture used for AI and IoT prototype development.

- Decentralized (D): Data is decentralized in terms of pattern recognition, anomaly or object detection, and predictive analysis. This enables local processing for real-time use, supports scalability in terms of the number of people with disabilities, and ensures the system’s availability and security. This architectural design is primarily used in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Mobility Impairment prototypes.

- Supporting Security (SS): Implements protection of people with disabilities data from intrusion and unauthorized access, such as access control methods and encryption.

- Supporting Privacy (SP): Supports privacy, especially in child and adult-sensitive apps by using anonymization techniques.

- Supporting Security and Privacy (SSP): A combination of security and privacy methodologies for total protection.

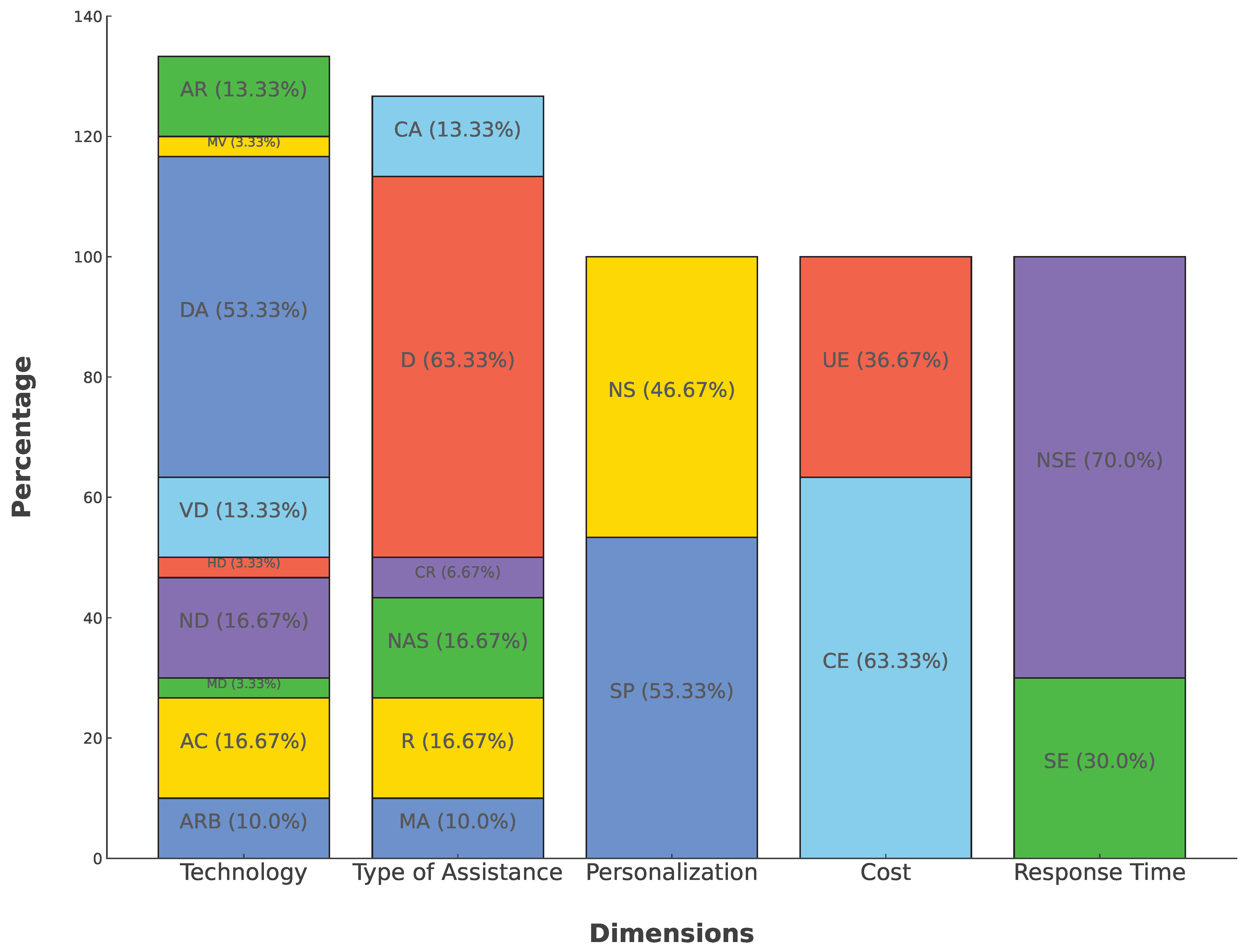

4.2.3. Disability Assistance Layer

- Assistive Robots (ARB): Physical and cognitive support, especially in mobility and rehabilitation tasks.

- Assistive Chatbots (AC): These provide conversational chat for communicating or cognitive rehabilitation.

- Mobility Devices (MD): These support people with mobility impairments by helping them move or enhance mechanical mobility and find directions.

- Navigation Devices (ND): These help people with disabilities to find the routes and find their way around easily.

- Hearing Devices (HD): These provide hearing and communication support to Hearing Impairment users or those having difficulties in hearing.

- Visual Devices (VD): They improve visual perception and navigation for Visual Impairment users.

- Diagnostic/Detection Assistance (DA): These are targeted towards diagnostic and anomaly or object detection in real time.

- Metaverse (MV): This provides virtual worlds in which avatars represent people with disabilities and helps in cognitive or physical therapy.

- Augmented Reality (AR): This provides augmented support for diagnostic, therapy, or communications.

- Mobility Assistance (MA): This facilitates patients with physical movement for Mobility Impairment.

- Rehabilitation (R): Therapeutic interventions for rehabilitation or adaptation.

- Navigation Assistance (NA): This leads people with disabilities through foreign landscapes in a comfortable and controlled manner.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation (CR): This improves cognitive function via instructed engagement.

- Diagnostic/Detection (D): This allows people with disabilities to detect objects or to identify hazards in real time.

- Communication Assistance (CA): This improves the communication skills of people with disabilities, especially in cases of speech or hearing loss.

- Supporting Personalization (SP): Individualized services based on personal preferences and needs.

- Not Supporting (NS): Standardized solutions that may not be flexible to particular user scenarios.

- Cost Effective (CE): Easy-to-use solutions can be delivered with an integrated functionality that is affordable.

- Uneconomical (UE): The system may provide more, but it is not affordable.

- Strong Emphasis (SE): Response-optimized for real-time support.

- No Strong Emphasis (NSE): The system has possible delays or lacks real-time communication.

5. Research Prototypes

5.1. Research Strategy

5.2. Overview of Major AI and IoT Disabilities Assistance Research Prototypes

5.2.1. Down Syndrome

5.2.2. Autism Spectrum Disorder

5.2.3. Mobility Impairment

5.2.4. Hearing Impairment

5.2.5. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

5.2.6. Visual Impairment

5.3. Evaluation of Major AI and IoT Disability Assistance Research Prototypes

- Common Success Factors: are having multimodal data acquisition with the help of IoT sensors, having personalization based on AI for an adaptive user experience, and having real-time feedback loops for maintaining user engagement and autonomy. These elements are associated with higher usability and impact in terms of therapy, and are present in many systems with positive results, regardless of the disability they serve, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, Visual Impairment, etc.

- Recurring Limitations: limited diversity of datasets, the absence of longitudinal trials, high costs of development and maintenance, and low involvement of users in the co-design process during development. Many systems show promising technical results in specific use cases, but few are validated at scale or face legal and regulatory limitations on real-world deployment.

- Emerging Trends: in the long term, we can identify several emerging trends, such as the use of a hybrid AI–IoT architecture for continuous monitoring, explainable AI to increase system interpretability, and edge computing for privacy-preserving inference. Taken together, these observations show an increasing interest in the field in developing more intelligent, ethical, and aware assistive ecosystems that can scale in size and accessibility while remaining affordable.

6. Open Issues and Research Directions in AI and IoT Assistive Disability

Limitations, Risks, and Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

References

- Hersh, M.A.; Johnson, M.A. Disability and assistive technology systems. In Assistive Technology for Visually Impaired and Blind People; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah, R.; Batra, P.K.; Jain, A. Internet of things architectural elements, challenges and future directions. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC), Noida, India, 5–7 March 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Papanastasiou, G.; Drigas, A.; Skianis, C.; Lytras, M.; Papanastasiou, E. Patient-centric ICTs based healthcare for students with learning, physical and/or sensory disabilities. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudda, S.; Haribabu, K. A review on WSN based resource constrained smart IoT systems. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.; Pitarma, R.M.; Garcia, N.; Pombo, N. Internet of things architectures, technologies, applications, challenges, and future directions for enhanced living environments and healthcare systems: A review. Electronics 2019, 8, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbal, A.; Hamouda, H.; Alnajim, A.M.; Khan, S.; Alrifaie, M.F. Privacy as a Lifestyle: Empowering assistive technologies for people with disabilities, challenges and future directions. J. King Saud-Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semary, H.; Al-Karawi, K.A.; Abdelwahab, M.M.; Elshabrawy, A. A Review on Internet of Things (IoT)-Related Disabilities and Their Implications. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanidis, C.; Salvendy, G. Designing for Usability, Inclusion and Sustainability in Human-Computer Interaction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, J.; Nicolle, C. Moving towards inclusive design guidelines for socially and ethically aware HCI. Interact. Comput. 2005, 17, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.M.; Polgar, J.M. Cook & Hussey’s Assistive Technologies; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rafii, M.S.; Kleschevnikov, A.M.; Sawa, M.; Mobley, W.C. Down syndrome. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 167, 321–336. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, D.; Light, J. The iPad and mobile technology revolution: Benefits and challenges for individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2013, 29, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, M.C.; Buzzi, M.; Perrone, E.; Senette, C. Personalized technology-enhanced training for people with cognitive impairment. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2019, 18, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.J. Cognitive Training Programs. In Innovations in Neurocognitive Rehabilitation: Harnessing Technology for Effective Therapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.B. Autism spectrum disorders—Diagnosis and management. Indian J. Pediatr. 2017, 84, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Almukhalfi, H.; Souza, A.; Noor, T.H. Harnessing YOLOv11 for Enhanced Detection of Typical Autism Spectrum Disorder Behaviors Through Body Movements. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, R.W.; Wendt, O. Effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: A systematic review. Am. J. -Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2008, 17, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.; Mitchell, P. The potential of virtual reality in social skills training for people with autistic spectrum disorders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2002, 46, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touch, D. Autistic Disorder, College Students, and Animals. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1992, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkery, M.; Wilmarth, M.A. Impaired Joint Mobility, Motor. In Musculoskeletal Essentials: Applying the Preferred Physical Therapist Practice Patterns; SLACK Incorporated: Thorofare, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith, M.J.; Kahle, J.T.; Miro, R.M.; Orendurff, M.S.; Lewandowski, A.L.; Orriola, J.J.; Sutton, B.; Ertl, J.P. Prosthetic interventions for people with transtibial amputation: Systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality prospective literature and systematic reviews. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2016, 53, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argall, B.D. Autonomy in rehabilitation robotics: An intersection. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 1, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.E.; Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Hickson, L. Functional consequences of impaired hearing in older adults and implications for intervention. In Aging and Hearing: Causes and Consequences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 257–291. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, N.R.; Pisoni, D.B.; Miyamoto, R.T. Cochlear implants and spoken language processing abilities: Review and assessment of the literature. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2010, 28, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, R.M.; Singer, A.C. Immersive Enhancement and Removal of Loudspeaker Sound Using Wireless Assistive Listening Systems and Binaural Hearing Devices. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, K.; Kersken, V.; Reuter, B.; Egger, N.; Zimmermann, G. Measuring the accuracy of automatic speech recognition solutions. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2024, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Briggs, A.I. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J. Pediatr. Neurol. 2011, 9, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibrian, F.L.; Lakes, K.D.; Schuck, S.E.; Hayes, G.R. The potential for emerging technologies to support self-regulation in children with ADHD: A literature review. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2022, 31, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, Z.; Vecchi, T.; Cornoldi, C.; Mammarella, I.; Bonino, D.; Ricciardi, E.; Pietrini, P. Imagery and spatial processes in blindness and visual impairment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008, 32, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.N.; Smith-Jackson, T.L.; Kleiner, B.M. Accessible haptic user interface design approach for users with visual impairments. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2014, 13, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Liang, L.; Wu, J.; Quan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, D. Automatic identification of Down syndrome using facial images with deep convolutional neural network. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahamiri, S.R.; Salim, S.S.B. Artificial neural networks as speech recognisers for dysarthric speech: Identifying the best-performing set of MFCC parameters and studying a speaker-independent approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2014, 28, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, P.D.; Vicnesh, J.; Gururajan, R.; Oh, S.L.; Palmer, E.; Azizan, M.M.; Kadri, N.A.; Acharya, U.R. Artificial intelligence enabled personalised assistive tools to enhance education of children with neurodevelopmental disorders—A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, C.; Li, Q. A survey of fog computing: Concepts, applications and issues. In Proceedings of the 2015 Workshop on Mobile Big Data, Brussels, Belgium, 22–23 June 2015; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Agiwal, M.; Roy, A.; Saxena, N. Next generation 5G wireless networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 1617–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicari, S.; Rizzardi, A.; Grieco, L.A.; Coen-Porisini, A. Security, privacy and trust in Internet of Things: The road ahead. Comput. Netw. 2015, 76, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Estève, D.; Escriba, C.; Campo, E. A review of smart homes—Present state and future challenges. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2008, 91, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Park, H.; Bonato, P.; Chan, L.; Rodgers, M. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.; Helal, S. RFID information grid for blind navigation and wayfinding. In Proceedings of the Ninth IEEE International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC’05), Osaka, Japan, 18–21 October 2005; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Tamayo, J.L.; Gertrudix Barrio, M.; García García, F. Immersive environments and virtual reality: Systematic review and advances in communication, interaction and simulation. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2017, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, G. A short history of human computer interaction: A people-centred perspective. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGUCCS Annual Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 7–10 October 2018; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, B.A. A brief history of human-computer interaction technology. Interactions 1998, 5, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, W.A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Darko, K.; Sanker, V.; Tan, J.K.; Pearl, T.O.; Ben-Jaafar, A.; Ranganathan, S.; Aderinto, N.; Mehta, A.; et al. Bridging minds and machines: The recent advances of brain-computer interfaces in neurological and neurosurgical applications. World Neurosurg. 2024, 189, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M. AI and Human Interaction: Enhancing User Experience Through Intelligent Systems. Front. Artif. Intell. Res. 2024, 1, 209–249. [Google Scholar]

- Malviya, R.; Rajput, S. AI-Driven Innovations in Assistive Technology for People with Disabilities. In Advances and Insights into AI-Created Disability Supports; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kranthi, B.J.; Suhas, G.; Varma, K.B.; Reddy, G.P. A two-way communication system with Morse code medium for people with multiple disabilities. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Prayagraj, India, 27–29 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, C.F.; Tseng, L.K.; Jang, Y. Pruning a decision tree for selecting computer-related assistive devices for people with disabilities. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2012, 20, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorosheva, T.; Novoseltseva, M.; Geidarov, N.; Krivosheev, N.; Chernenko, S. Neural network control interface of the speaker dependent computer system «Deep Interactive Voice Assistant DIVA» to help people with speech impairments. In Proceedings of the Third International Scientific Conference “Intelligent Information Technologies for Industry”(IITI’18), Sochi, Russia, 17–21 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Kiangala, S.K.; Wang, Z. An effective adaptive customization framework for small manufacturing plants using extreme gradient boosting-XGBoost and random forest ensemble learning algorithms in an Industry 4.0 environment. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2021, 4, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Kaur, L.; Neeru, N. A new improved obstacle detection framework using IDCT and CNN to assist visually impaired persons in an outdoor environment. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 124, 3685–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoladore, D.; Negri, L.; Arlati, S.; Mahroo, A.; Fossati, M.; Biffi, E.; Davalli, A.; Trombetta, A.; Sacco, M. Towards a knowledge-based decision support system to foster the return to work of wheelchair users. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 24, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, T.; Peng, J. Logic-enhanced adaptive network-based fuzzy classifier for fall recognition in rehabilitation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57105–57113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namoun, A.; Humayun, M.A.; BenRhouma, O.; Hussein, B.R.; Tufail, A.; Alshanqiti, A.; Nawaz, W. Service selection using an ensemble meta-learning classifier for students with disabilities. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Rahimi, M.; Moazzamigodarzi, M.; Liu, Y.; Dutta Pramanik, P.K.; Heravi, M.A.; Mehbodniya, A.; Ghaderzadeh, M.; Feylizadeh, M.R.; et al. Deep learning: Applications, architectures, models, tools, and frameworks: A comprehensive survey. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2023, 8, 581–606. [Google Scholar]

- Abdolrasol, M.G.; Hussain, S.S.; Ustun, T.S.; Sarker, M.R.; Hannan, M.A.; Mohamed, R.; Ali, J.A.; Mekhilef, S.; Milad, A. Artificial neural networks based optimization techniques: A review. Electronics 2021, 10, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Deep learning: A comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashar, A.A.K.; Abrar, A.; Liu, J. A Survey on Deep Learning-based Smart Assistive Aids for Visually Impaired Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Information System and Data Mining, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–12 May 2023; pp. 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- ZainEldin, H.; Gamel, S.A.; Talaat, F.M.; Aljohani, M.; Baghdadi, N.A.; Malki, A.; Badawy, M.; Elhosseini, M.A. Silent no more: A comprehensive review of artificial intelligence, deep learning, and machine learning in facilitating deaf and mute communication. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, M.; Furnari, A.; Medioni, G.G.; Trivedi, M.; Farinella, G.M. Deep learning for assistive computer vision. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Ding, Y.; Long, L.; Li, W.; Xu, X. Advancements in Smart Wearable Mobility Aids for Visual Impairments: A Bibliometric Narrative Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haux, R.; Hein, A.; Kolb, G.; Künemund, H.; Eichelberg, M.; Appell, J.E.; Appelrath, H.J.; Bartsch, C.; Bauer, J.M.; Becker, M.; et al. Information and communication technologies for promoting and sustaining quality of life, health and self-sufficiency in ageing societies–outcomes of the Lower Saxony Research Network Design of Environments for Ageing (GAL). Inform. Health Soc. Care 2014, 39, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stan, I.E.; D’Auria, D.; Napoletano, P. A Systematic Literature Review of Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions in Telemonitoring and Wearable Health Technologies. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 99, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrančić, A.; Zadravec, H.; Orehovački, T. The role of smart homes in providing care for older adults: A systematic literature review from 2010 to 2023. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1502–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollineni, C.; Sharma, M.; Hazra, A.; Kumari, P.; Manipriya, S.; Tomar, A. IoT for Next-Generation Smart Healthcare: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 32616–32639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Xiang, W. Artificial intelligence of things for smarter healthcare: A survey of advancements, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1261–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, N.; Singh, J. A survey of research trends in assistive technologies using information modelling techniques. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkova, K.; Krasniqi, V.; Dalipi, F.; Ferati, M. Cutting-edge communication and learning assistive technologies for disabled children: An artificial intelligence perspective. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 970430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Segal, S. A review of internet of things technologies for ambient assisted living environments. Future Internet 2019, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, U.b.; Naeem, M.; Stasolla, F.; Syed, M.H.; Abbas, M.; Coronato, A. Impact of AI-powered solutions in rehabilitation process: Recent improvements and future trends. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 943–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wambuaa, R.N.; Oduorb, C.D. Implications of Internet of Things (IoT) on the Education for students with disabilities: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Res. Public 2022, 102, 378–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimoor, N.; Rehman, S. Reliable and resilient AI and IoT-based personalised healthcare services: A survey. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, M.P.; Piai, V.A.; Farias, R.H.; Fernandes, A.M.; de Moraes Rossetto, A.G.; Leithardt, V.R.Q. Artificial intelligence of things applied to assistive technology: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavric, A.; Beguni, C.; Zadobrischi, E.; Căilean, A.M.; Avătămăniței, S.A. A comprehensive survey on emerging assistive technologies for visually impaired persons: Lighting the path with visible light communications and artificial intelligence innovations. Sensors 2024, 24, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Islam, M.M.; Shehata, S.; Karray, F.; Quintana, Y. Smart healthcare in the age of AI: Recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145248–145270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathne, N.N.; Kagita, M.K.; Gadekallu, T.R. The role of the internet of things in health care: A systematic and comprehensive study. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2020, 10, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Khan, M.B. Enhanced Medical Education for Physically Disabled People through Integration of IoT and Digital Twin Technologies. Systems 2024, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, M. IoT and artificial intelligence implementations for remote healthcare monitoring systems: A survey. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4687–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.C. An overview of machine learning and 5G for people with disabilities. Sensors 2021, 21, 7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.J.; Siddiqui, F.; Zeadally, S.; Lane, D. A review of IoT systems to enable independence for the elderly and disabled individuals. Internet Things 2023, 21, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudar, S.S.; Albahri, A.S.; Hamid, R.A.; Zahid, I.A.; Alqaysi, M.E.; Albahri, O.S.; Alamoodi, A.H. Artificial intelligence-based approaches for improving the diagnosis, triage, and prioritization of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of current trends and open issues. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 53–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Loiacono, E.T.; Kordzadeh, N. Smart cities for people with disabilities: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2023, 33, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report, EBSE Technical Report; Keele University: Newcastle, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oyuela, F.Z.; Paz, Ó.A. AI-powered backup robot designed to enhance cognitive abilities in children with Down syndrome. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Central America and Panama Student Conference (CONESCAPAN), Guatemala, 26–29 September 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Peraković, D.; Periša, M.; Cvitić, I.; Zorić, P. Application of the Internet of Things Concept to Inform People with Down Syndrome. In Proceedings of the XL Simpozijum o Novim Tehnologijama u Poštanskom i Telekomunikacionom Saobraćaju–PosTel 2022, Beograd, Serbia, 29–30 November 2022; pp. 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Do, H.D.; Allison, J.J.; Nguyen, H.L.; Phung, H.N.; Tran, C.D.; Le, G.M.; Nguyen, T.T. Applying machine learning in screening for Down Syndrome in both trimesters for diverse healthcare scenarios. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavaluru, D.; Ravula, S.R.; Auguskani, J.P.L.; Dharmarajlu, S.M.; Chellathurai, A.; Ramakrishnan, J.; Mugaiahgari, B.K.M.; Ravishankar, N. Advancing Fetal Ultrasound Diagnostics: Innovative Methodologies for Improved Accuracy in Detecting Down Syndrome. Med. Eng. Phys. 2024, 126, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Banna, M.H.; Ghosh, T.; Taher, K.A.; Kaiser, M.S.; Mahmud, M. A monitoring system for patients of autism spectrum disorder using artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Brain Informatics, Padua, Italy, 19 September 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Shahamiri, S.R.; Thabtah, F. Autism AI: A new autism screening system based on artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.L.; Popescu, N.; Dobre, C.; Apostol, E.S.; Popescu, D. IoT and AI-based application for automatic interpretation of the affective state of children diagnosed with autism. Sensors 2022, 22, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, N.A.; Rao, S.; Verma, A.K.; Kasana, S.S. Autism Spectrum Disorder Detection Using AI and IoT. In Proceedings of the 2022 Fourteenth International Conference on Contemporary Computing, Noida, India, 4–6 August 2022; pp. 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, A.; Zhao, Q.; Bangyal, W.H.; Iqbal, M. Analysis of brain imaging data for the detection of early age autism spectrum disorder using transfer learning approaches for Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 70, 4478–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Alagirisamy, M.; Xi, C.; Balasubramanian, V.; Srinivasan, R.; Parvathi, R.; Jhanjhi, N.; Islam, S.M. AI and IoT-enabled smart exoskeleton system for rehabilitation of paralyzed people in connected communities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 80340–80350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldolaim, R.J.; Gull, H.; Iqbal, S.Z. Boxly: Design and Architecture of a Smart Physical Therapy Clinic for People Having Mobility Disability Using Metaverse, AI, and IoT Technologies in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Information Technology, Electronics and Intelligent Communication Systems (ICITEICS), Bangalore, India, 28–29 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vourganas, I.; Stankovic, V.; Stankovic, L. Individualised responsible artificial intelligence for home-based rehabilitation. Sensors 2020, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, H.A.; Alharbi, K.K.; Hassan, C.A.U. Enhancing elderly fall detection through IoT-enabled smart flooring and AI for independent living sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morollón Ruiz, R.; Garcés, J.A.C.; Soo, L.; Fernández, E. The Implementation of Artificial Intelligence Based Body Tracking for the Assessment of Orientation and Mobility Skills in Visual Impaired Individuals. In Proceedings of the International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation, Olhâo, Portugal, 31 May–3 June 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 485–494. [Google Scholar]

- Ozarkar, S.; Chetwani, R.; Devare, S.; Haryani, S.; Giri, N. AI for accessibility: Virtual assistant for hearing impaired. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 1–3 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vinitha, I.; Kalyani, G.; Prathyusha, K.; Pavan, D. AI-Enabled Sign Language Detection: Bridging Communication Gaps for the Hearing Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2024 Control Instrumentation System Conference (CISCON), Manipal, India, 2–3 August 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh Kannan, S.; Ezhilarasi, P.; Rajagopalan, V.G.; Krishnamithran, S.; Ramakrishnan, H.; Balaji, H.K. Integrated AI based smart wearable assistive device for visually and hearing-impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics and Communication (ICRTEC), Mysore, India, 10–11 February 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, T.H.; Noor, A.; Alharbi, A.F.; Faisal, A.; Alrashidi, R.; Alsaedi, A.S.; Alharbi, G.; Alsanoosy, T.; Alsaeedi, A. Real-Time Arabic Sign Language Recognition Using a Hybrid Deep Learning Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekeš, E.R.; Galzina, V.; Kolar, E.B. Using human-computer interaction (hci) and artificial intelligence (ai) in education to improve the literacy of deaf and hearing-impaired children. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1375–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Tachmazidis, I.; Chen, T.; Adamou, M.; Antoniou, G. A hybrid AI approach for supporting clinical diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2020, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristiyanti, N.; Dirgantoro, B.; Setianingsih, C. Behavioral disorder test to identify Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children using fuzzy algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things and Intelligence Systems (IoTaIS), Bandung, Indonesia, 23–24 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Soria, I.; Rico-Juan, J.R.; Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R.; Lavigne-Cervan, R. Prediction of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder based on explainable artificial intelligence. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2024, 14, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, H.; Aldhyani, T.H.; Ahmed, Z.A.; Alqarni, A.A. Developing System-Based Artificial Intelligence Models for Detecting the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gong, S. Potential attempt to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (adhd) children with engineering education games. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa, V.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, S. AI based automated image caption tool implementation for visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Industrial Electronics Research and Applications (ICIERA), New Delhi, India, 22–24 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shandu, N.E.; Owolawi, P.A.; Mapayi, T.; Odeyemi, K. AI based pilot system for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Computing and Data Communication Systems (icABCD), Durban, South Africa, 6–7 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ratheesh, R.; Sri Rakshaga, S.R.; Asan Fathima, A.; Dhanusha, S.; Harini, A. AI-Based Smart Visual Assistance System for Navigation, Guidance, and Monitoring of Visually Impaired People. In Proceedings of the 2024 Ninth International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (ICONSTEM), Chennai, India, 4–5 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Abhishek, S.; Sathish, H.; Kumar, A.; Anjali, T. Aiding the visually impaired using artificial intelligence and speech recognition technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 21–23 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1356–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Lai, R.; Guo, B.; Liu, L.; He, L.; Zhao, Y. AI-Vision: A Three-Layer Accessible Image Exploration System for People with Visual Impairments in China. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Asghar, Z.; Kumar, T.; Li, G.; Manzoor, A.; Mikhaylov, K.; Shah, S.A.; Höyhtyä, M.; Reponen, J.; Huusko, J.; et al. Emerging technologies for next generation remote health care and assisted living. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 56094–56132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmannai, W.; Elleithy, K. Sensor-based assistive devices for visually-impaired people: Current status, challenges, and future directions. Sensors 2017, 17, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskovitz, J. DIY Assistive Software: End-User Programming for Personalized Assistive Technology. ACM SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2024, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamaan, H.; Tahaei, M.; Buijsman, S.; Xiao, Z.; Wilkinson, D.; Knijnenburg, B.P. The Role of Human-Centered AI in User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization—Models, Frameworks, and Paradigms. In A Human-Centered Perspective of Intelligent Personalized Environments and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 43–83. [Google Scholar]

- Andò, B.; Baglio, S.; Castorina, S.; Marletta, V.; Crispino, R. On the assessment and reliability of assistive technology: The case of falls and postural sway monitoring. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2021, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A.; Adhikari, M.; Amgoth, T.; Srirama, S.N. A comprehensive survey on interoperability for IIoT: Taxonomy, standards, and future directions. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharudin, R.; Izhar, N.A.; Hwa, D.L. Evaluating mobile application as assistive technology to improve students with learning disabilities for communication, personal care and physical function. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.T.; Lee, Y.H.; Wang, Y.F. Developing Assistive Technology Products Based on Experiential Learning for Elderly Care. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Traditional Assistive Technologies | AI/IoT-Based Assistive Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | Static, predefined functions | Learns user behavior through AI models and adaptive feedback |

| Data Processing | Manual or device-specific | Automated, real-time data analytics via IoT and cloud |

| Personalization | Limited or user-configured only | Dynamic personalization through ML and user-context modeling |

| Response Time | Delayed or event-triggered | Real-time response via edge/IoT computation |

| Scalability | Difficult to expand | Modular and easily extensible via connected devices |

| Interactivity | One-way (device to user) | Bidirectional communication using speech, gesture, or environmental sensors |

| Maintenance | Frequent manual calibration | Self-learning updates reduce maintenance frequency |

| Accessibility | Local use only | Remote accessibility via IoT networks |

| Prototype | Focus | Technology | Data Source | Data Type | Environment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [84] | DS | RP | C | I | ID | ||||

| [85] | DS | IoT, BT | S | TD, DL | OD | ||||

| [31] | DS | NA | C | I | ID | ||||

| [86] | DS | NA | SI | I | ID | ||||

| [87] | DS | NA | SI | I | ID | ||||

| [88] | ASD | IoT | S | I, DL | ID | ||||

| [89] | ASD | IoT | SI, TI | I | ID | ||||

| [90] | ASD | IoT, RP, BT | C, S | I, TD | ID | ||||

| [91] | ASD | IoT, AR, RFID | C, S | I, TD | ID | ||||

| [92] | ASD | IoT | SI | I, TS | ID | ||||

| [93] | MI | IoT, AR, LoRa | C, S | I, TD | ID | ||||

| [94] | MI | IoT | C, S | I, TD | ID | ||||

| [95] | MI | IoT | S | TD | ID | ||||

| [96] | MI | IoT, RFID | S | TD | ID | ||||

| [97] | VI, MI | IoT | C | VF | ID | ||||

| [98] | HI | NA | C, M | VF, AD | OD | ||||

| [99] | HI | NA | C | I, VF | ID | ||||

| [100] | HI, VI | IoT, LoRa | C, S | I, DL | OD | ||||

| [101] | HI | NA | C | I, VF | ID | ||||

| [102] | HI | NA | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [103] | ADHD | NA | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [104] | ADHD | NA | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [105] | ADHD | NA | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [106] | ADHD | NA | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [107] | ADHD | IoT | TI | TD | ID | ||||

| [108] | VI | NA | C | I | ID, OD | ||||

| [109] | VI | RP | C, S | I, DL | ID, OD | ||||

| [110] | VI | RP | C, S | I, DL | ID, OD | ||||

| [111] | VI | NA | M | AD | ID | ||||

| [112] | VI | NA | C | I, TS | ID, OD | ||||

| Focus | Technology | Data Source | Data Type | Environment | |||||

| DS | Down Syndrome | IoT | Internet of Things | C | Camera | I | Images | ID | In-Door |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder | RP | Raspberry Pi | S | Sensors | DL | People with Disabilities Location | OD | Out-Door |

| MI | Mobility Impairment | AR | Arduino | SI | Scanned Images | VF | Video Frames | ||

| HI | Hearing Impairment | BT | Bluetooth | TI | Text Input | TS | Time-Series | ||

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | LoRa | Long Range Communication | M | Microphone | TD | Text Data | ||

| VI | Visual Impairment | RFID | Radio Frequency Identification | AD | Audio Data | ||||

| NA | Not Applicable | ||||||||

| Prototype | Technique | Model | Parameters | Architecture | Security and Privacy (S & P) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [84] | ML | SVM | FR, CH | C | SS | ||||

| [85] | ML | NA | CH, NR | C | N | ||||

| [31] | DL | CNN | FR | C | N | ||||

| [86] | ML | XGBoost | CH, BO | C | N | ||||

| [87] | DL | CNN | CH, BO | C | SSP | ||||

| [88] | DL | CNN | FR | DC | N | ||||

| [89] | DL | CNN | CH, A, BM | DC | N | ||||

| [90] | DL | CNN | CH, DR | DC | N | ||||

| [91] | DL | CNN | FR, CH | DC | N | ||||

| [92] | DL | CNN | BO | C | N | ||||

| [93] | DL | ANN | BM | DC | SS | ||||

| [94] | DL | CNN | BM | DC | N | ||||

| [95] | DL | XGBoost, KNN | BM | C | SS | ||||

| [96] | ML | KNN | E, BM | C | SP | ||||

| [97] | DL | YOLOv8 | NR | C | N | ||||

| [98] | DL | CNN, LSTM | BM | C | N | ||||

| [99] | DL | CNN | BM | C | N | ||||

| [100] | DL | CNN | FR, NR | DC | N | ||||

| [101] | DL | CNN, LSTM | BM | DC | SS | ||||

| [102] | HCI | NA | CH, BM | C | N | ||||

| [103] | ML | DT, KM | A, B | C | SP | ||||

| [104] | ML | Fuzzy | CH, B | C | N | ||||

| [105] | ML | RF | CH, B | C | N | ||||

| [106] | ML, DL | CNN, M-Layer Perceptron | CH, BO | C | N | ||||

| [107] | HCI | NA | CH, BO | C | N | ||||

| [108] | DL | CNN, LSTM | VP | C | N | ||||

| [109] | DL | CNN | VP | C | N | ||||

| [110] | DL | CNN | NR, VP | C | N | ||||

| [111] | ML | Mel Freq. Cepstral Coeff. | VP | C | N | ||||

| [112] | ML | OpenCV | VP | C | SP | ||||

| Technique | Model | Parameters | Architecture | S & P | |||||

| ML | Machine Learning | SVM | Support Vector Machine | FR | Facial Recognition | C | Centralized | SS | Supporting Security |

| DL | Deep Learning | CNN | Convolutional Neural Network | CH | Children | D | Decentralized | SP | Supporting Privacy |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction | XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting | A/E | Adults/Elderly | SSP | Supporting Security and Privacy | ||

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network | NR | Navigation Routes | N | None | ||||

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor | BO | Body Organs | ||||||

| YOLO | You Only Look Once | DR | Drawing | ||||||

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory | BM | Body Motors | ||||||

| DT | Decision Tree | B | Behavior | ||||||

| KM | Knowledge Model | VP | Visual Perception | ||||||

| RF | Random Forest | ||||||||

| NA | Not Applicable | ||||||||

| Prototype | Technology | Type of Assistance | Personalization | Cost | Response Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [84] | ARB | CR | SP | UE | NSE | ||||

| [85] | ND | NAS | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [31] | DA | D | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [86] | DA | D | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [87] | DA | D | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [88] | DA | D | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [89] | DA | D | SP | CE | SE | ||||

| [90] | AC, DA | D | SP | UE | SE | ||||

| [91] | DA | D | SP | UE | NSE | ||||

| [92] | DA | D | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [93] | ND, MD | MA, R | SP | UE | SE | ||||

| [94] | MV, ARB | MA, R | SP | CE | NSE | ||||

| [95] | DA | MA, R | SP | UE | SE | ||||

| [96] | DA | D | NS | UE | SE | ||||

| [97] | ND | NAS | SP | CE | SE | ||||

| [98] | AC, HD | NAS, CA | SP | CE | SE | ||||

| [99] | DA | CA | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [100] | ARB | NAS | SP | UE | SE | ||||

| [101] | AC | CA | NS | CE | SE | ||||

| [102] | AR | CR, CA | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [103] | DA | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [104] | DA | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [105] | DA | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [106] | DA | D | NS | UE | NSE | ||||

| [107] | DA | D | NS | UE | NSE | ||||

| [108] | VD | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [109] | ND, VD | NAS, D | NS | UE | NSE | ||||

| [110] | ND, VD | NAS, D | NS | UE | NSE | ||||

| [111] | AC, VD | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| [112] | AC | D | NS | CE | NSE | ||||

| Technology | Type of Assistance | Personalization | Cost | Response Time | |||||

| ARB | Assistive Robot | MA | Mobility Assistance | SP | Supporting Personalization | CE | Cost Effective | SE | Strong Emphasis |

| AC | Assistive Chatbot | R | Rehabilitation | NS | Not Supporting | UE | Uneconomical | NSE | No Strong Emphasis |

| MD | Mobility Devices | NAS | Navigation Assistance | ||||||

| ND | Navigation Devices | CR | Cognitive Rehabilitation | ||||||

| HD | Hearing Devices | D | Diagnostic/Detection | ||||||

| VD | Visual Devices | CA | Communication Assistance | ||||||

| DA | Diagnostic/Detection Assistance | ||||||||

| MV | Metaverse | ||||||||

| AR | Augmented Reality | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Noor, A.; Almukhalfi, H.; Atlam, E.-S.; Noor, T.H. Supporting Disabilities Using Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things: Research Issues and Future Directions. Disabilities 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities6010003

Noor A, Almukhalfi H, Atlam E-S, Noor TH. Supporting Disabilities Using Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things: Research Issues and Future Directions. Disabilities. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoor, Ayman, Hanan Almukhalfi, El-Sayed Atlam, and Talal H. Noor. 2026. "Supporting Disabilities Using Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things: Research Issues and Future Directions" Disabilities 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities6010003

APA StyleNoor, A., Almukhalfi, H., Atlam, E.-S., & Noor, T. H. (2026). Supporting Disabilities Using Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things: Research Issues and Future Directions. Disabilities, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities6010003