Perceptions of People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of New Zealand’s Built Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To rank different types of public spaces (buildings and their surrounds) by perceived ease of access for people with widely varying disabilities;

- To determine the effect of different types of disabilities on the perceived main barriers (a) outside buildings, (b) at the entrance to buildings and, (c) inside buildings;

- To identify the top priorities for improving inclusive access to the built environment.

2. Materials and Methods

- The respondent lived anywhere in New Zealand;

- The respondent lived with a disability of any type or types, including but not limited to their mobility, vision, hearing, age, cognition, and sensory abilities;

- The respondent visited any public buildings or spaces regularly, for example, monthly—this criterion excluded people who mostly remained in residences and medical facilities;

- The respondent was eighteen years or older—people under the age of eighteen and carers were excluded from the survey as a condition imposed by the university’s ethics committee.

- Ease of access of 29 different types of public buildings or spaces (Table 2) using a 5-point Likert scale where 5 is Very Hard; 4 is Hard; 3 is Ok; 2 is Easy; and 1 is Very Easy. Respondents could choose an additional option: “I do not go there”.

- Open-ended responses to the most challenging aspect outside or around buildings.

- Open-ended responses to the most challenging aspect of the building entrance.

- Open-ended responses to the most challenging aspect inside the building.

- Open-ended responses on the top priority for improving access to the built environment.

3. Results

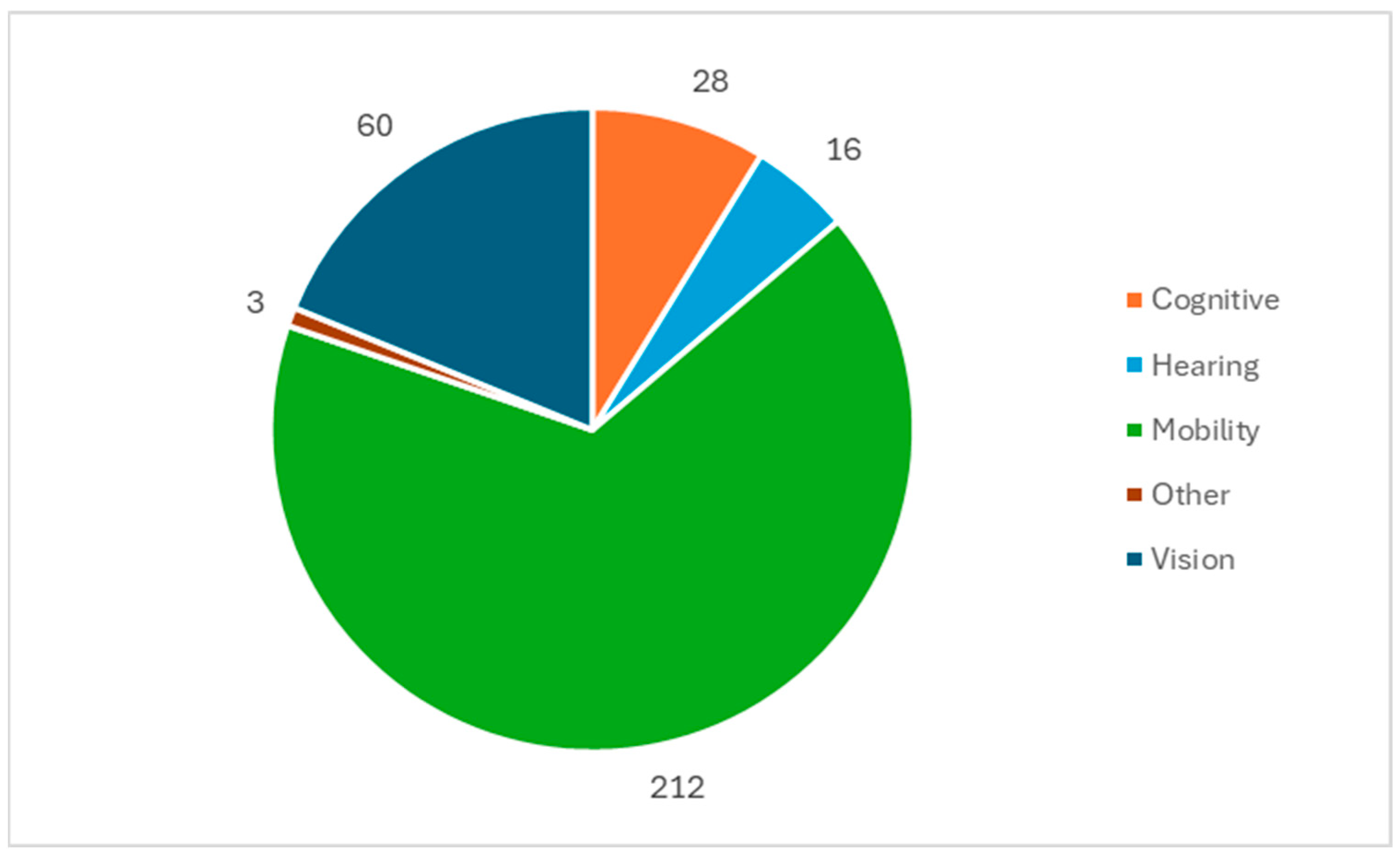

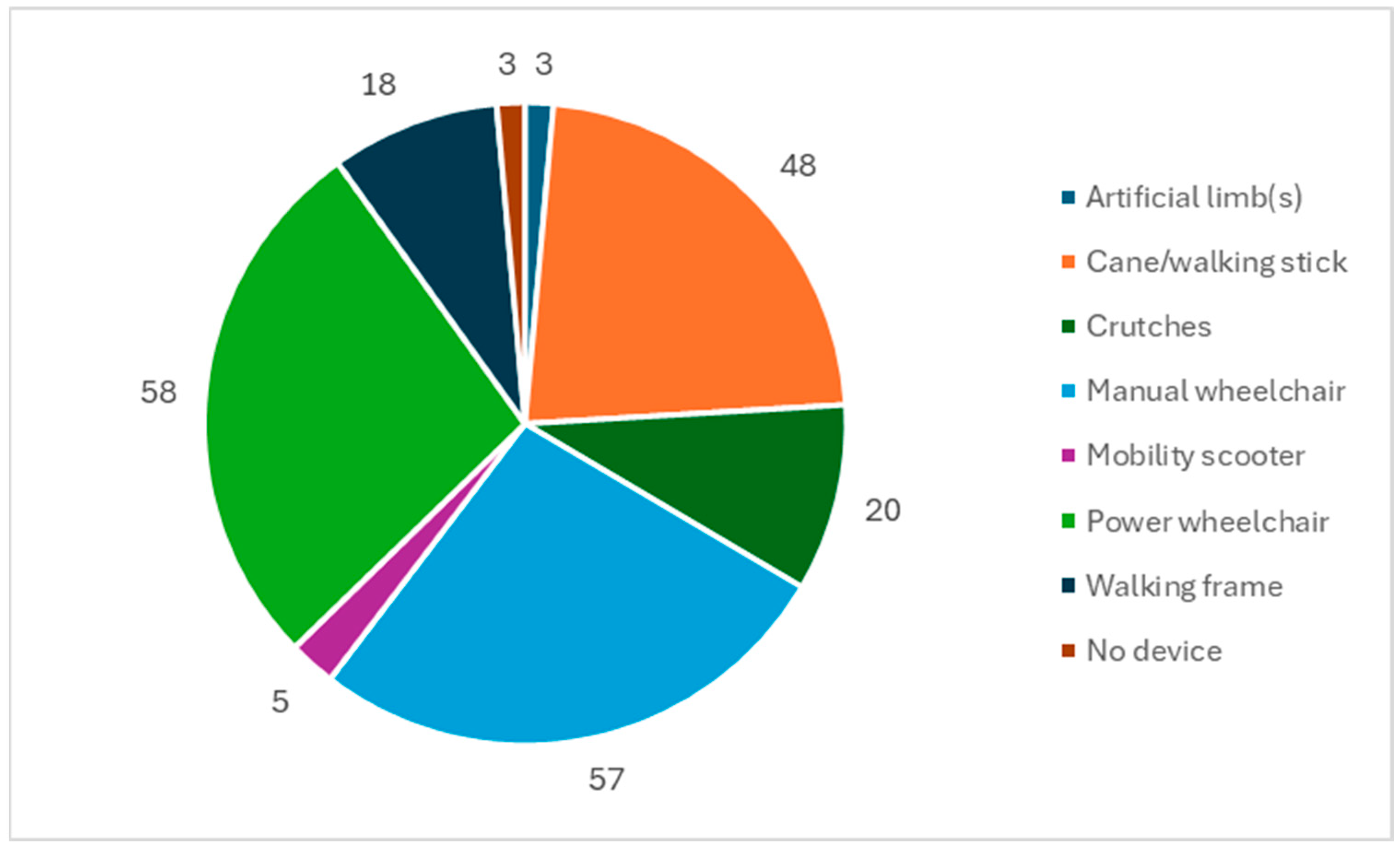

3.1. Demographics of the Respondents

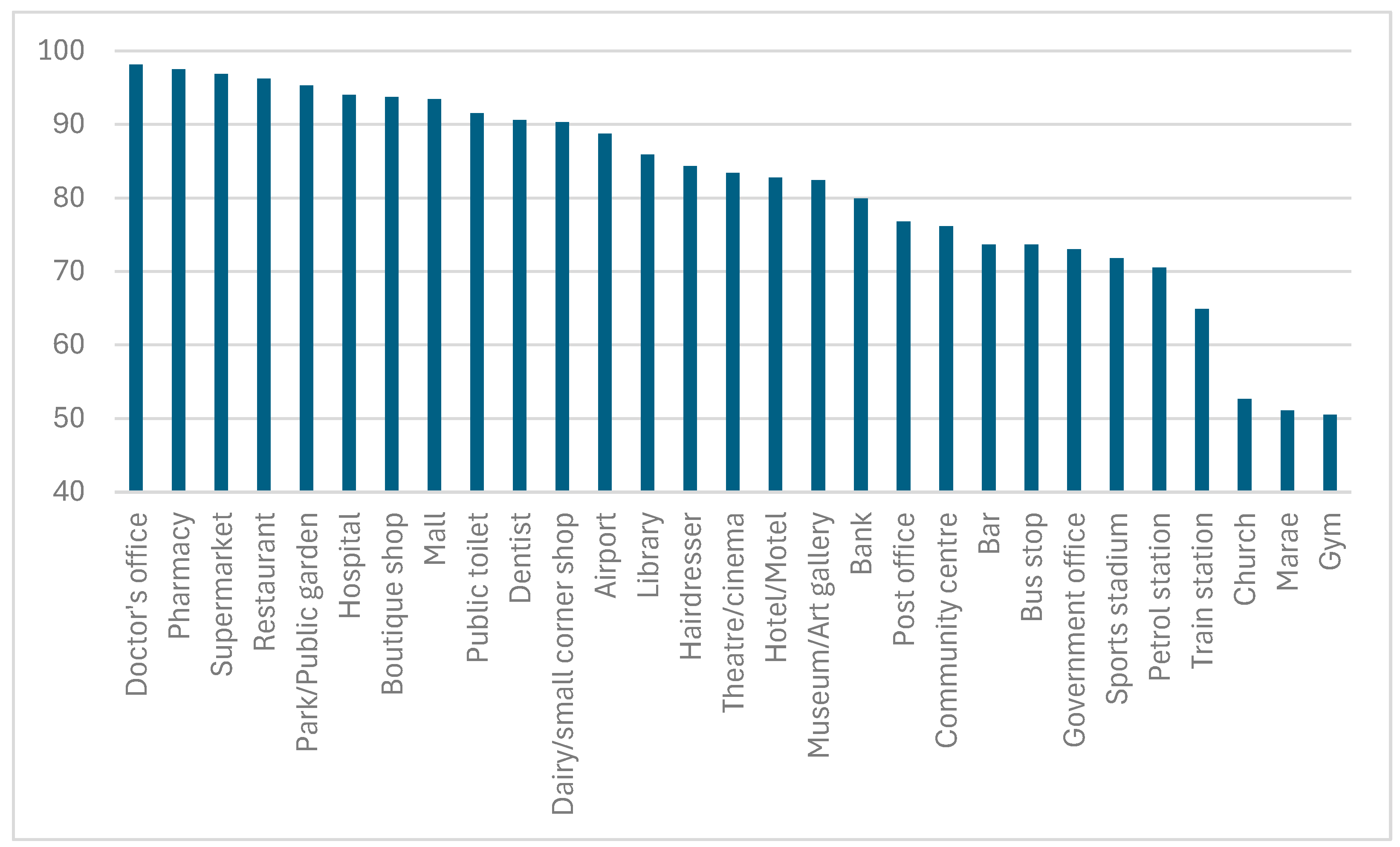

3.2. Ranking Different Types of Public Buildings by Difficulty of Access (Research Objective One)

3.3. Accessibility Challenges for People with Mobility Impairments

3.3.1. Main Barriers Outside, at the Entrance and Inside Buildings (For People with Mobility Impairment)

3.3.2. Priorities for Improved Accessibility (For People with Mobility Impairment)

- All design should be Safe, Obvious and Step-free (SOS);

- Adopt Universal Design in all buildings, not as an afterthought;

- Consult with the community;

- Make access a law for all public buildings—give building owners two years to comply;

- Provide online accessibility information for venues to help with planning.

3.4. Accessibility Challenges for People with Vision Impairments

3.4.1. Main Barriers Outside, at the Entrance and Inside Buildings (For People with Vision Impairment)

| Rank | Priority | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Obstacles in path | 34.7 | People, traffic, uneven paths, potholes, unmarked steps, steps without a handrail, curbs, signs/displays, animals, tables, construction zones, bridges. |

| 2 | Wayfinding | 32.0 | Difficulty finding: the route, main entrance, correct door, a safe route (avoiding cars), the correct building itself, steps, ramp. |

| 3 | Signage | 10.7 | Absence of large signage indicating the entrance (both at the door and at the footpath showing the direction to the door), unclear/small signs (for directions, parking restrictions and safety warnings), signs with poor contrast, few/no Braille or audio cues. |

| 4 | Other | 22.7 | Doors: poor contrast with surrounds (particularly glass ones). Safety concerns: no footpaths or pedestrian crossings, walking amongst cars. Poor colour contrast, inadequate lighting, weather (such as rain or snow) obscures obstacles and makes surfaces slippery, poor screen readability, limited tactile markings, feeling judged by people, getting assistance, social isolation. |

| Rank | Priority | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Access control | 29.5 | Complex manual/automatic door control (e.g., fitted with a child lock, requiring security card, pin code or phone to access), knowing whether glass sliding door is open/which way it slides, locating door handles, unmarked opening direction, sudden and loud alarms on doors. |

| 2 | Finding entrance | 21.8 | Identifying entrances that match the façade, unmarked doors/doors without signs (particularly café/restaurant doors). |

| 3 | Door type | 19.2 | Heavy manual doors are hard to open (particularly when using a guide dog, wheelchair or walker), narrow doors, revolving doors are very difficult, unmarked glass doors, low-contrast doors. |

| 4 | Obstacles | 16.7 | Entrance steps (particularly unmarked and without handrail), entrance lip, people, objects (plants, benches, debris) near the door, and weather barriers (e.g., vestibules, awnings, or canopies) that obscure the doorway. |

| 5 | Other | 12.8 | Dim lighting (relative to outdoors) obscures obstacles and makes it hard to see signage, getting assistance, signs/directions near the entrance with small text, inadequate tactile marking and braille, slippery entrance surface. |

| Rank | Priority | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wayfinding | 33.0 | Few navigation cues or directions (to show position of reception desk, merchandise, counter, queue line, lift, stairs, accessible bathroom), complex layout, no receptionist/person to assist, only vision-based information. |

| 2 | Signage | 14.3 | Inadequate signs/screens (small text, poor contrast), black tape barriers at airports (yellow tape is more visible), lack of audible/tactile signage. |

| 3 | Obstacles | 14.3 | People, steps (particularly unmarked), escalators, furniture, doors, debris, construction materials. |

| 4 | Paths | 11.0 | No/unmarked walkways (especially in large open spaces), shiny/patterned floors, narrow paths (through people moving in different directions, or restaurant tables), uneven floors, moving walkways. |

| 5 | Other | 27.4 | Lifts: locating them, no braille/audible information, out of service. Lighting: too dim (especially in restrooms), too variable. Service: Lack of reception/staff to assist. Miscellaneous: few rest places, poor acoustics (loud background noise or echoes), sensory overload, poor air quality (from smoking or chemicals), guide dog-prohibited. |

3.4.2. Priorities for Improved Accessibility (For People with Vision Impairment)

- Consider safety, predictability and reliability;

- Unfortunately, there isn’t only one thing;

- While physical access has improved, little has been done for access for blind people; Better signage would help but one needs to know it’s there and where it is; feeling around the walls is not “a good look” and is not helpful;

- Acceptance of and provision for guide dogs;

- Provision of affordable public transport;

- More accurate entrance location on Google Maps.

3.5. Accessibility Challenges for People with Hearing Impairments

3.5.1. Main Barriers Outside, at the Entrance and Inside Buildings (For People with Hearing Impairment)

3.5.2. Priorities for Improved Accessibility (For People with Hearing Impairment)

3.6. Accessibility Challenges for People with Sensory, Cognitive and Neuro-Diverse Impairments

3.6.1. Main Barriers Outside, at the Entrance and Inside Buildings (For People with Sensory/Cognition Impairment)

3.6.2. Priorities for Improved Accessibility (For People with Sensory/Cognition Impairment)

4. Discussion

- Outside buildings: Keep paths short (or provided with seating), smooth, wide, properly differentiated, clear of objects, well-maintained (no cracks and potholes), safe from cars, and with adequate curb cuts. Provide enough accessible parking spaces with adequate clearance (including overhead). Use direction and information signs for all important features, such as parking, main entrance, and ramps. Signage should be inclusive, i.e., in large text, braille, universal images, and audio messages.

- Building entrances: Use automatic- or easy-open doors, that are prominent, remain open long enough, and are clear of obstacles such as steps, lips, canopies, notice boards, mats and plants. Avoid card/pin access control systems and call button assistance that is non-inclusive (for example, requiring the person to have quick responses, good vision or good hearing). Provide stairs and ramps (not too steep) with handrails close to the entrance. Increase light level in the entrance to accommodate eyes adjusting from sunlight outside.

- Inside buildings: Use simple layouts with clear and inclusive navigation and information signage (easy to understand, visual, braille and audible) for all key features (such as the reception/assistance area, lifts, and accessible bathrooms) and for public announcements. Keep paths level, smooth, non-slip, plain matte finish, well-differentiated (e.g., with tactile marking), clear of obstacles (particularly display stands) and adequately wide. Use clear markings and continuous handrails on stairs and ensure that lifts have adequate space and inclusive operation/information. Provide accessible bathrooms with easy-open doors, standard layout, adult changing facilities, good clearance space and regular maintenance. Control lighting and acoustics to minimise glare, flashing/strobing lights, beeping and loud noises and provide seating/rest areas, particularly where people need to walk far or stand for long periods.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Abbreviations

| APD | Auditory Processing Disorder |

| APP | Accessibility Partnership Panel |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SPD | Sensory Processing Disorder |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNCRPD | United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disability |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO World Health Organization. Disability: Key Facts, 7 March 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Statistics New Zealand. Household Disability Survey: 2023, ISBN 978-1-991307-44-6, pp. 1–36. 2025. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/household-disability-survey-2023-findings-definitions-and-design-summary/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- UNCRPD, 2006 United Nations, 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)—Articles. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- United Nations 2015. Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 11. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Watchorn, V.; Hitch, D.; Grant, C.; Tucker, R.; Aedy, K.; Ang, S.; Frawley, P. An integrated literature review of the current discourse around universal design in the built environment–is occupation the missing link? Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zallio, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the built environment: A study of architectural design practice. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, G.; Slaug, B.; Schmidt, S.M.; Norin, L.; Ronchi, E.; Gefenaite, G. A scoping review of public building accessibility. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemmer, C.; McIntosh, A. Equitable access to the built environment for people with disability. Athens J. Technol. Eng. 2024. Available online: https://www.athensjournals.gr/ajte/forthcoming (accessed on 14 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mosca, E.I.; Capolongo, S. Design for all AUDIT (Assessment Universal Design & Inclusion Tool). A tool to evaluate physical, sensory-cognitive and social quality in healthcare facilities. Acta Biomed. 2023, 94, e2023124. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, U.I.; Jawabrah, M.Q.; Jarada, A. Adaptation of accessibility for people with disabilities in private and public buildings using appropriate design checklist. Int. J. Mod. Trends Sci. Technol. 2020, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Padalabalanarayanan, S.; Malone, L.A.; Mehta, T. Fitness facilities still lack accessibility for people with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZS 4121:2001; Design for Access and Mobility—Buildings and Associated Facilities. Standards New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2001.

- Stefanitsis, M.; Flemmer, C.; Rasheed, E.; Ali, N.A. Accessibility to the Built Environment for Mobility-Impaired Persons: A Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering, Project, and Production Management, Auckland, New Zealand, 29 November–1 December 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chidiac, S.E.; Reda, M.A.; Marjaba, G.E. Accessibility of the built environment for people with sensory disabilities—Review quality and representation of evidence. Build 2024, 14, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsalis, E.; Jaeger, N.; Hale, J. Disabled-by-design: Effects of inaccessible urban public spaces on users of mobility assistive devices—A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkia, C.; Reid, D.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Kairy, D.; Rushton, P.W.; Demers, L.; Archambault, P.S. Power wheelchair driving challenges in the community: A users’ perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoung, D.A.; Baada, F.N.A.; Baayel, P. Access to library services and facilities by persons with disability: Insights from academic libraries in Ghana. J. Librar. Inf. Sci. 2021, 53, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeamwatthanachai, W.; Wald, M.; Wills, G. Indoor navigation by blind people: Behaviors and challenges in unfamiliar spaces and buildings. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2019, 37, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthirathna, W.A.D.; Karunasena, G.; Rodrigo, V.A.K. Disability access in public buildings. In Proceedings of the International Research Conference on Sustainability in Built Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 18–19 June 2010; pp. 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, M. Environmental accessibility for autistic individuals: Recommendations for social work practice and spaces. Aotearoa New Zealand Soc. Work Rev. 2022, 34, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijadunola, M.Y.; Ojo, T.O.; Akintan, F.O.; Adeyemo, A.O.; Afolayan, A.S.; Akanji, O.G. Engendering a conducive environment for university students with physical disabilities: Assessing availability of assistive facilities in Nigeria. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2018, 14, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaer, M.; Baumers, S.; Heylighen, A. Autism-friendly architecture from the outside in and the inside out: An explorative study based on autobiographies of autistic people. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 31, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangaard, S.; Hedvall, P.-O.; Lid, I.M. Universal design and accessibility as an act or a state—A comparison of policies in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 320, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Warnicke, C.; Kristianssen, A.-C. Safety and accessibility for persons with disabilities in the Swedish transport system—Prioritization and conceptual boundaries. Disabil. Soc. 2024, 39, 2357–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Cotes, L.; Horton, B.; Kunac, R.; Snell, I.; Taylor, B.; Wright, A.; Devan, H. “Enticing” but not necessarily a “space designed for me”: Experiences of urban park use by older adults with disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.R.; Purcal, C. Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, A.; Schijlen, J.; Van der Linden, V.; Meulenijzer, D.; Vermeersch, P.-W. Socially innovating architectural design practice by mobilising disability experience. An exploratory study. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2016, 12, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P.; Mackinnon, K.; Darcy, S.; Almond, B. Public toilets for accessible and inclusive cities: Disability, design and maintenance from the perspective of wheelchair users. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Calder-Dawe, O.; Carroll, P.; Kayes, N.; Kearns, R.; Lin, E.-Y.; Witten, K. Mobility barriers and enablers and their implications for the wellbeing of disabled children and young people in Aotearoa New Zealand: A cross-sectional qualitative study. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon-David, H.; Siekanska, M.; Tenenbaum, G. Are gyms fit for all? A scoping review of the barriers and facilitators to gym-based exercise participation experienced by people with physical disabilities. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2021, 9, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutuncu, O. Investigating the accessibility factors affecting hotel satisfaction of people with physical disabilities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutuncu, O.; Lieberman, L. Accessibility of hotels for people with visual impairments: From research to practice. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2016, 110, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazzan, W. My accessible room is not accessible, applying human factors: Principals to enhance the accessibility of hotel rooms. Proced. Manuf. 2015, 3, 5405–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gamache, S.; Routhier, F.; Morales, E.; Vandersmissen, M.-H.; Boucher, N. Mapping review of accessible pedestrian infrastructures for individuals with physical disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 14, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, A.P. City accessible for everyone–improving accessibility of public transport using the universal design concept. Transp. Res. Proc. 2016, 14, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.W.; Tuttle, M.; Spann, E.; Ling, C.; Jones, T.B. Addressing accessibility within the church: Perspectives of people with disabilities. J. Relig. Health 2023, 62, 2474–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, J.; Harrison, C.; Eekhoff, A.; Marthaler, C.; Seromik, M.; Ogren, S.; VanderMolen, J. Identifying Barriers to Accessibility for Museum Visitors Who Are Blind and Visually Impaired. Visit. Stud. 2023, 26, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsami, C.A.; Chrysikou, E. Towards specialized accessibility standards for healthcare facilities: A mixed-methods study on the needs of people with dis-abilities in hospitals. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 319, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Swainea, B.; Labbé, D.; Poldma, T.; Baril, M.; Fichten, C.; Havel, A.; Kehayia, E.; Mazer, B.; McKinley, P.; Rochette, A. Exploring the facilitators and barriers to shopping mall use by persons with disabilities and strategies for improvements: Perspectives from persons with disabilities, rehabilitation professionals and shopkeepers. J. Disabil. Stud. 2024, 12, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, F.; Berget, G. Inclusive public libraries: How to adequately identify accessibility barriers? Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2024, 320, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsak, H.I. Assessing building accessibility for university students with disabilities. MOJ Yoga Phys. Ther. 2018, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, B.A.; Martinis, J.G.; Pagano, G.F.; Barthol, S.; Senzer, J.; Williamson, P.R.; Blanck, P.D. The Americans with Disabilities Act and equal access to public spaces. Laws 2024, 13, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.; Bringa, O.R. From visions to practical policy: The Universal Design journey in Norway. What did we learn? What did we gain? What now? In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Universal Design, York, UK, 21–24 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, Y.; Heider, A.; Labbe, D.; Gould, R.; Jones, R. Planning accessible cities: Lessons from high quality barrier removal plans. Cities 2024, 148, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, A. Rethinking ADA signage standards for low-vision accessibility. J. Vis. 2017, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. Legislative recognition of the human right to accessible housing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Pub. Int. LJNZ 2021, 8, 128–150. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, A.; Sole, G.; Mulligan, H. The accessibility of fitness centers for people with disabilities: A systematic review. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, M.; Chauhan, D.; Patil, S.; Kangas, R.; Heer, J.; Froehlich, J.E. Urban accessibility as a socio-political problem: A multi-stakeholder analysis. Proc. ACM Hum-Comp. Inter. 2021, 4, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H.; Hitch, D.; Watchorn, V.; Ang, S. Working with policy and regulatory factors to implement universal design in the built environment: The Australian experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2015, 12, 8157–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemmer, C.; McIntosh, A. Making New Zealand’s Built Environment Inclusive and Accessible for Everyone. BRANZ Research Report ER104, 2025; pp. 1–55. Available online: https://www.branz.co.nz/pubs/research-reports/er104/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Calculator.net. Available online: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=95&ci=5&pp=24&ps=5400000&x=Calculate (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Öhrvall, A.M.; Wennberg, B.; Käcker, P.; Lidström, H. Experiences of participation in people with intellectual disability, in relation to service support received, and views from professionals in the field of disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Engel, C.; Loitsch, C.; Stiefelhagen, R.; Weber, G. Traveling more independently: A study on the diverse needs and challenges of people with visual or mobility impairments in unfamiliar indoor environments. ACM Trans. Access. Comp. 2022, 15, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.P.; Mendonca, R.J.; Smith, R.O. Accessibility of public buildings in the United States: A cross-sectional survey. Disabil. Soc. 2024, 39, 2988–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, N.; Gere, B.; Mora, E.; Chen, R.K. Navigating the Path: Understanding and overcoming challenges for college students with disabilities. In Innovative Approaches in Counselor Education for Students With Disabilities; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 141–196. [Google Scholar]

- Alhusban, A.A.; Almshaqbeh, S.N. Delivering an inclusive built environment for physically disabled people in public universities (Jordan as a case study). J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 22, 1980–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Zhang, D.; Dulas, H.M.; Whirley, M.L. Academic learning experiences and challenges of students with disabilities in higher education. J. Postsecond. Stud. Success 2024, 3, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okezue, O.C.; Uzoigwe, M.; Ugwu, L.E.; John, J.N.; John, D.O.; Mgbeojedo, U.G. Level of independence, anxiety and relevant challenges among persons with disabilities towards their use of facilities in public buildings. Facilities 2024, 42, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangfang, H.; Xiao, H.; Shuai, Z.; Qiong, W.; Jingya, Z.; Guodong, S.; Yan, Z. Living Environment, Built Environment and Cognitive Function among Older Chinese Adults: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 9, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area | Key Research Themes and Source |

|---|---|

| Access barriers for different types of disability | Most studies consider challenges associated with physical impairments such as mobility [14,15,16] |

| Access barriers associated with vision and hearing impairment [17,18,19] | |

| Access barriers associated with cognitive and neurodiverse impairments [20,21,22] | |

| Impairments may vary in number (one or more), severity and duration and are more common in older people [23,24,25] | |

| Social barriers, e.g., negative treatment and ableist attitudes of other people [26,27] | |

| Access for different types of buildings | Public toilets [28], Marae 1 [29], gyms [30], hotels [31,32,33], public transport facilities [34,35], religious places [36], museums [37], medical centres [38], shopping malls [39], libraries [40], university facilities [41]. |

| Accessibility legislation | Disability strategies, anti-discrimination legislation, building codes and standards aimed at inclusive access [23,42,43] |

| Comprehensive policy and strict enforcement in the USA [44,45] | |

| Application and limitations of New Zealand accessibility policy [46,47] | |

| Community driven change and fair funding allocation [48,49] |

| Type | Type | Type | Type | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supermarket | Bar | Government office | Airport | Museum/gallery |

| Shopping mall | Doctor’s office | Community centre | Bus stop | Boutique shop |

| Hospital | Dentist | Hotel/motel | Train station | Pharmacy |

| Marae 1 | Petrol station | Church | Cinema/theatre | Dairy 2 |

| Hairdresser | Bank | Sports stadium | Gym | Public toilet |

| Restaurant | Post office | Park/garden | Library |

| Demographic | N | Category and Percentage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 291 | 18–24 | 25–44 | 45–64 | 65–86 |

| 4.5% | 45.0% | 33.0% | 17.5% | ||

| Gross Income (1000 NZD) | 252 | <30 | 30–59 | 60–99 | >100 |

| 23.8% | 22.6% | 26.6% | 27.0% | ||

| Work status | 270 | Full time | Part time | Unemployed | Retired |

| 34.5% | 24.8% | 20.7% | 20.0% | ||

| Health status 1 | 285 | Mostly well | 1–2 p.a. | 4–12 p.a. | In-home care |

| 29.1% | 22.5% | 35.1% | 13.3% | ||

| Rank | Barrier | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paths | 22.2 | Cracked, potholes, rough (gravel), poorly maintained. |

| 2 | Accessible parking | 13.1 | Missing/too few, inadequate van/lift clearance (particularly overhead in covered parking), too far away, on a slope. |

| 3 | Obstacles on paths | 12.1 | Bollards, trolleys, scooters, cars over footpath, recycling bins, gutters, planters, people. |

| 4 | Travel distance | 12.1 | Too long, too far from accessible parking to the ramp or from the ramp to the entrance, more seating needed. |

| 5 | Curb cuts | 11.1 | Missing, too high, poorly maintained. |

| 6 | Wayfinding | 11.1 | Too complex, inadequately sign posted or marked, no pedestrian crossing/unsafe (exposure to cars), no path from accessible parking to footpath. |

| 7 | Other | 18.3 | Steps: No handrail (especially necessary when wet), no markings. Ramps: Too steep, missing, placed at rear of building or not obvious, access to ramp blocked. Traffic: No protected path, wheelchairs are low and not visible to traffic. Exposure to weather makes everything harder. |

| Rank | Barrier | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Door type | 27.2 | Too heavy (especially fire doors), transparent/poor contrast doors are hard to see, double doors where one is locked and it is not obvious which door to use, revolving doors are a health/safety risk—wheelchairs can get jammed in there, automatic doors close too quickly. |

| 2 | Obstacles | 20.7 | Steps or objects in front of entrance, high threshold/lip, uneven surface, mats, plants obscuring handrails. |

| 3 | Access control | 18.5 | Manual door is difficult/hard to push, hard to locate/grip the handle (e.g., when using a walking stick), complex controls, opening in/out is hard to determine. |

| 4 | Width | 17.4 | Too narrow, not enough clearance |

| 5 | Other | 16.2 | Finding entrance: Poor/no sign to show where it is, incorrectly labelled as wheelchair accessible. Ramp: Missing or not in an obvious place near the entrance. |

| Rank | Barrier | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Narrow aisles | 21.8 | Insufficient space to move/turn. |

| 2 | Obstacles in paths | 18.8 | Merchandise display stands, people, furniture. |

| 3 | Wayfinding | 14.9 | Complex layouts, lack of or poor signage/instructions, accessible bathrooms hidden. |

| 4 | Lifts/stairs | 9.9 | No lifts, buttons/card reader hard to reach, too narrow to turn, stairs without handrails. |

| 5 | Other | 34.6 | Shelves/counters/card readers: unreachable (too high, especially sliding doors on top of refrigerator cabinets), inadequate clearance. Related to other disabilities: Vision (lighting, small font on notices), stroke (one-sided queues), hearing (unable to follow verbal instructions), sensory (lighting, noise). Rest areas: no/few seats in waiting areas and on long paths, inadequate space for wheelchairs. Accessible bathrooms: Not available, inadequate clearance, not maintained, no adult changing facilities, problematic doors. Path surface: Slippery, highly polished, thick carpet, too steep. Emergency escape route: difficult to find and use, heavy fireproof doors. Rude people, poorly designed furniture (no clearance for wheelchair). |

| Rank | Priority | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Doors | 32.8 | Should open automatically with adequate open time, wider doors, clear indicators for direction of opening, level path in/out of doorway, button operated fire doors, doorbell or intercom assistance, Braille instructions. |

| 2 | Diverse impairments | 15.6 | Many people with mobility impairment also have other impairments (e.g., sensory, neurodivergent, deaf, vision, age-related, etc.). |

| 3 | Aisles/paths | 12.5 | Wide enough, clear of objects, level, smooth non-slip surface, no thick pile carpet. |

| 4 | Ramps | 10.9 | Available at all entrances where there are stairs, with handrails, not too steep. |

| 5 | Other | 28.2 | Wayfinding: clear signage with large text, multi-mode instructions (pictorial, Braille, audible, screen display), large entrance/exit signs visible from a distance, safe from cars. Stairs/lifts: handrails on stairs, clear instructions on how to operate lifts, accessible lift controls, adequate lift space. Rest areas: more seating, especially in waiting areas and on long travel distances. Accessible bathrooms: with adult changing station, adequate space, easy-open doors, well-maintained. Provide physical access that does not rely on a keycard or provide quick assistance. |

| Rank | Priority | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wayfinding | 31.9 | Use a standardised layout (e.g., prominent entrance, no steps near doors, identification signs on doors), simple navigation paths, audible or tactile navigation cues, non-shiny flooring (plain, matte finish is best), more detailed layout maps. |

| 2 | Signage | 17.0 | High contrast, large text instructions, tactile and braille signage. |

| 3 | Doors/ entrance | 12.8 | High visibility handle, good contrast with background, clearly labelled, blind-friendly markings on glass doors, automated doors, distinct ramp near main entrance. |

| 4 | Obstacles | 10.6 | Reduced exposure to hazards (e.g., traffic, sharp corners, hard surfaces, moving doors, display stands), clear paths, well-differentiated steps (with good colour contrast), standardised emergency protocols. |

| 5 | Assistance | 10.6 | Prominent service area, tactile ridge for paths through large spaces, audible/braille directions to key facilities (assistance, queue line, toilets), audio descriptions. |

| 6 | Other | 17.1 | Stairs/ramps/lifts: Stairs with uniform height and tread depth, adequate handrails (particularly at direction changes, extending to the end of the last step, at hand-level); more ramps; and verbal cues for lifts. Accessible restrooms: standardised layout (fixed position of rails and dispensers) and lock type, more available, restricted use (e.g., with a universal key). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flemmer, C.; McIntosh, A. Perceptions of People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of New Zealand’s Built Environment. Disabilities 2025, 5, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030075

Flemmer C, McIntosh A. Perceptions of People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of New Zealand’s Built Environment. Disabilities. 2025; 5(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlemmer, Claire, and Alison McIntosh. 2025. "Perceptions of People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of New Zealand’s Built Environment" Disabilities 5, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030075

APA StyleFlemmer, C., & McIntosh, A. (2025). Perceptions of People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of New Zealand’s Built Environment. Disabilities, 5(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030075