1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and positive childhood experiences (PCEs) are increasingly recognized as important determinants of children’s psychosocial development and long-term health. ACEs, such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, have been associated with developmental delays, behavioral problems, and mental health challenges [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. If unaddressed, these effects may persist into adulthood, contributing to elevated risks of anxiety and self-injurious behaviors [

8,

9,

10]. In contrast, PCEs—such as supportive relationships, stable home environments, positive school experiences, and peer acceptance—have been shown to promote resilience, improve psychosocial outcomes, and buffer the impact of adversity [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. While ACEs have been extensively studied in the general population, PCE frameworks are more recent and still emerging. Their application to specific populations, including children with intellectual disabilities, remains limited and underexplored.

This scoping review focuses on psychosocial outcomes relevant to children with intellectual disabilities, including—but not limited to—developmental, behavioral, and mental health indicators. In this review, psychosocial outcomes are broadly defined as encompassing emotional well-being, behavioral functioning, social relationships, and adaptive skills relevant to daily life and overall functioning. This definition is informed by the World Health Organization’s conceptualization of psychosocial health as involving emotional, interpersonal, and functional dimensions [

16]. The unique neurodevelopmental, cognitive, and social characteristics of children with intellectual disabilities may influence how ACEs and PCEs and related constructs shape these outcomes [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. For instance, heightened sensitivity to stress and limited coping mechanisms may amplify the impact of adversity [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], while barriers such as limited access to supportive relationships or stable environments can diminish the benefits of PCEs [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Communication difficulties may hinder the recognition and processing of experiences, thereby complicating both their assessment and the interaction between internal and external resilience factors [

33,

34]. Moreover, children with intellectual disabilities are often disproportionately exposed to adversity, including social exclusion, bullying, and economic hardship, further increasing their risk of negative psychosocial outcomes [

20,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Despite these vulnerabilities, ACE and PCE frameworks have rarely been explicitly adapted to the unique needs of children with intellectual disabilities [

40]. Conceptually related constructs—such as traumatic experiences, life events, resilience factors, and supportive relationships [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]—align closely with established ACE [

46] and PCE [

47,

48] definitions and provide a valuable foundation for tailoring these frameworks to children with intellectual disabilities. In the general population, ACEs are typically assessed using the original 10-item CDC-Kaiser ACE questionnaire [

7], while PCEs are commonly measured with tools such as the Benevolent Childhood Experiences (BCE) scale [

49]. Recognizing and situating these constructs within the broader ACE and PCE frameworks offers an opportunity to unify existing knowledge and provide deeper insights into the cumulative and interconnected nature of childhood experiences in shaping psychosocial outcomes for children with intellectual disabilities. Bridging these frameworks is critical for advancing research and developing effective interventions that address the specific needs of children with intellectual disabilities.

Resilience theory offers a relevant conceptual foundation for this review, providing a framework to understand how adverse and positive experiences interact in shaping psychosocial outcomes. Established models distinguish between risk factors that increase vulnerability, promotive factors that enhance development, and protective factors that buffer against adversity [

50,

51]. This tripartite model aligns with ACE and PCE frameworks, which conceptualize childhood experiences as interdependent influences on long-term functioning. Although resilience models have rarely been adapted to the needs of children with intellectual disabilities, they offer a valuable lens for examining how cognitive, communicative, and social–environmental factors interact to influence psychosocial development. As Raghavan and Griffin [

44] note, resilience in children with intellectual disabilities remains undertheorized—highlighting the need for more inclusive, developmentally attuned conceptual models.

The limited existing evidence indicates a high prevalence of ACEs among children with intellectual disabilities, particularly in institutional settings. Exploratory studies indicate that 81.7% of children with intellectual disabilities and 92.3% of those with borderline intellectual functioning (BIF) in residential care have experienced at least one ACE, with emotional neglect and household dysfunction being the most common experiences [

40,

52]. While this study focuses exclusively on children with intellectual disabilities, research among children with BIF provides valuable complementary insights into the long-term effects of ACEs. Studies suggest associations between early adversities and disruptions in neural connectivity, cognitive and behavioral challenges [

53], and increased psychiatric morbidity risks in adulthood [

54]. Although these findings cannot be directly extrapolated to children with intellectual disabilities, they underscore the broader impact of ACEs on neurodevelopment and psychosocial functioning. However, the specific mechanisms through which ACEs and PCEs shape psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities remain insufficiently understood, highlighting multiple critical gaps in the literature.

Current ACE and PCE frameworks often overlook the unique ecological stressors experienced by children with intellectual disabilities, such as social exclusion, out-of-home placements, institutional living, and high dependency on caregivers [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. In addition, standardized definitions and measurement tools are often ill-suited to the communicative, developmental, and cognitive profiles of this population. These limitations hinder reliable identification and assessment of adverse and positive experiences, complicating cross-study comparisons and synthesis [

44,

63]. While these challenges cannot be fully resolved within the scope of a scoping review, mapping how existing research conceptualizes and measures these experiences in children with intellectual disabilities is a critical first step toward more inclusive models.

A preliminary search of PsycInfo, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Open Science Framework (OSF), and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence Synthesis revealed no existing or ongoing systematic or scoping reviews that specifically address ACEs and PCEs in children with intellectual disabilities. While related reviews on trauma and adversity in individuals with intellectual disabilities provide important insights into the broader impact of life events across the lifespan, they do not examine these experiences within established ACE and PCE frameworks or focus specifically on psychosocial outcomes in childhood [

39,

42,

64,

65]. These gaps highlight the need for a comprehensive synthesis of the existing literature. A scoping review is particularly suited to this aim, as it enables a systematic mapping of how ACEs, PCEs, and conceptually related constructs have been defined, operationalized, and associated with psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities [

66]. This review is guided by two central questions: (1) How have ACEs, PCEs, and related constructs been conceptualized, operationalized, and measured in studies involving children with intellectual disabilities? (2) What is currently known about the associations between these experiences and psychosocial outcomes in this population? By identifying conceptual trends, methodological limitations, and knowledge gaps, this review primarily aims to inform future empirical research. Such research may, in turn, contribute to the development of inclusive, developmentally attuned conceptual models, which could ultimately help guide multistage systems of support—including prevention, intervention, and policy—tailored to the specific developmental profiles and support needs of children with intellectual disabilities.

2. Review Question

This scoping review systematically maps and evaluates existing research on ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs, and their associations with psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. ACE-/PCE-related constructs refer to experiences that are conceptually aligned with established ACE and PCE frameworks, even if not explicitly labeled as such in the original studies. By addressing this gap, the review aims to identify the range, conceptualization, and measurement of relevant childhood experiences in children with intellectual disabilities, and to explore how these constructs are associated with psychosocial outcomes.

This review was guided by the following central question: How have ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs been conceptualized, operationalized, and associated with psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities?

To address this overarching question, the following sub-questions were examined:

How are ACEs, PCEs, and related constructs defined and measured in studies involving children with intellectual disabilities?

What psychosocial outcomes are associated with these experiences?

What methodological or conceptual gaps exist in this body of literature?

These questions not only aim to synthesize current knowledge on childhood adversity and positive experiences but also to contribute to the development of a more integrated framework that can inform future research, interventions, and policies tailored to the needs of children with intellectual disabilities.

3. Inclusion Criteria

3.1. Participants

This review included studies that focused on experiences occurring before the age of 18 in individuals with intellectual disabilities, regardless of whether the data were collected during childhood or retrospectively in adulthood. As is consistent with widely used definitions in ACE research and international conventions, childhood was defined as the period up to age 18 [

67,

68]. To be eligible, studies needed to clearly operationalize intellectual disabilities based on formal diagnoses from international guidelines (e.g., AAIDD, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5, ICD-10, or ICD-11). Studies were also included if they explicitly stated that children had an official intellectual disability diagnosis, even if specific diagnostic criteria were not detailed. In cases where diagnostic criteria were unclear, proxy measures for intelligence quotient (IQ) or adaptive functioning were accepted if consistent with established thresholds (IQ < 70). Potential differences between boys and girls were noted, and studies with both retrospective and prospective designs were eligible for inclusion, focusing on their impact on psychosocial outcomes.

3.2. Concept

This review examines the relationship among ACEs, PCEs, and psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. While studies on children with intellectual disabilities rarely use the exact terms ACEs and PCEs, many investigate conceptually related constructs under different labels. To facilitate clarity and terminological consistency throughout the review, we use the descriptive term “ACE-/PCE-related constructs” to refer to experiences conceptually aligned with ACE and PCE frameworks, even when not explicitly labeled as such in the original studies.

To ensure a comprehensive and inclusive approach, the search strategy incorporated a broad range of terms related to childhood adversity and positive childhood experiences (

Supplementary Table S1). Eligibility was assessed using predefined inclusion criteria derived from prominent conceptual models. For ACEs, we applied the five characteristics defined by Kalmakis and Chandler [

46]: harmful events occurring in familial or social contexts, resulting from acute trauma or chronic exposures, and often leading to cumulative distress. For PCEs, we followed the definition by Guo et al. [

47], emphasizing experiences and conditions that promote flourishing and healthy development. Additionally, domains from validated PCE measures [

48] were considered, including stable and nurturing environments, supportive relationships with caregivers, peers and teachers, and opportunities for social engagement.

Beyond constructs explicitly included in the original ACE and PCE frameworks, we also included ACE-/PCE-related constructs that have emerged in ACE and PCE research in the general population as relevant to these frameworks. Examples include peer victimization as an ACE and positive parent–child relationships as a PCE. Although these may be labeled differently in the original studies (e.g., as “life events”, “family adversity”, or “supportive factors”), their content and function often overlap with ACEs and PCEs. This approach ensured a more comprehensive representation of ACEs and PCEs while maintaining relevance to children with intellectual disabilities.

Two independent reviewers systematically assessed the identified constructs against the predefined inclusion criteria, resolving discrepancies through joint discussions to ensure consistency. This process ensured that only the constructs demonstrating conceptual alignment with established ACE–PCE definitions were included, while allowing for contextual relevance to the intellectual disabilities population.

3.3. Context

To enhance understanding of these experiences across different environments, this review included studies involving children with intellectual disabilities from various cultural contexts and geographic locations. Differences between countries regarding the types of ACEs and PCEs experienced were documented in the results, contributing to a nuanced understanding of how these experiences may manifest in diverse contexts. Studies published in all languages were included to ensure a comprehensive overview of the existing literature.

3.4. Types of Sources

This scoping review considered a variety of study designs, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. No restrictions were placed on experimental or observational designs, provided that the studies addressed the relationship between ACEs or PCEs and psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. Systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and gray literature (e.g., theses, editorials, letters, and conference proceedings) were screened at the full-text level for citation searching only, as this review focused on direct evidence from original studies examining these relationships.

4. Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [

66] and was reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

69]. This review was guided by an a priori protocol, which was registered on OSF (

https://osf.io/haz59/?view_only=f07356f07f9548f49741e60e5dfb56fa, accessed on 10 March 2025).

4.1. Amendments to the Protocol

The aims and research questions of this scoping review were refined to enhance clarity and ensure better alignment with the study objectives, while maintaining the overall scope. The revised research questions provide a more precise focus on the conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement of ACEs, PCEs, and closely related constructs, ensuring a systematic approach to identifying how these constructs have been studied in relation to psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities.

Additionally, the distinction between developmental, behavioral, and mental health outcomes was consolidated into the broader category of psychosocial outcomes to enhance conceptual consistency across studies. These subcategories were part of the data extraction tool; however, during data extraction, analysis, and reporting, it became evident that many outcomes did not fit neatly into a single category. For example, self-regulation difficulties can be conceptualized as a developmental issue (executive functioning), a behavioral outcome (impulsivity, aggression), or a factor associated with social adjustment and maladaptive behaviors, such as aggression and hyperactivity [

70]. To reflect this complexity while maintaining methodological rigor, outcomes were synthesized under the broader umbrella of psychosocial outcomes in the Results Section (

Section 5).

In addition, the requirement for studies to justify the use of IQ data or proxy-IQ measures was refined to ensure a more inclusive approach, allowing for studies that assessed intellectual disabilities based on educational classification, clinical diagnosis, or standardized cognitive assessments. This adjustment prevents the unnecessary exclusion of studies where intellectual disabilities were identified through clinically and contextually appropriate methods, ensuring a more comprehensive representation of the existing literature.

Furthermore, while the protocol initially specified that literature reviews, scoping and systematic reviews, and gray literature—such as theses, editorials, book chapters, conference proceedings—would not be included in the review, these sources were used for citation searching. Although gray literature often provides valuable insights, particularly in under-researched populations such as children with intellectual disabilities, it was excluded from data extraction in order to preserve methodological consistency and ensure a focus on peer-reviewed empirical evidence. However, their reference lists were manually screened to identify additional primary studies relevant to the research questions. This strategy allowed us to incorporate potentially relevant sources indirectly, while upholding the review’s focus on quality-assured, peer-reviewed studies.

4.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to identify studies examining ACEs, PCEs, or related constructs in children with intellectual disabilities, focusing on their associations with psychosocial outcomes. A comprehensive, three-step search strategy was employed in this review. An initial limited search was conducted in Google Scholar and CataloguePlus, which searches the collections of the University of Amsterdam (UvA) Library. This preliminary search aimed to identify key studies and relevant literature on the topic, helping to refine and inform the development of the full search strategy for the review. Based on the results of the initial search, a comprehensive search strategy was developed using text words found in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, along with the index terms used to describe these articles. This strategy was then adapted for each database and information source used in the review (see

Supplementary Table S1). The following databases and information sources were searched: PsycInfo (Ovid), MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), Web of Science Core Collection, and Google Scholar. For Google Scholar, we first identified the top 100 most cited ACE and PCE articles using Publish or Perish. In addition, we manually screened 160 ACE-related and 110 PCE-related articles directly in Google Scholar to ensure that less-cited but potentially relevant studies were also considered. The lower number of PCE-related articles reflects the limited availability of relevant results during the search process. Citation searching was conducted manually by screening the reference lists of relevant articles, particularly systematic and scoping reviews, as well as other articles that cited primary studies included in this review. Studies published in any language were included to ensure a comprehensive exploration of the literature. The search was conducted without language limitations. Non-English articles were translated using machine translation tools and subsequently assessed for eligibility based on the predefined inclusion criteria. Studies published from 2009 to 8 October 2024 were included, reflecting the emergence of ACEs as a formalized construct in child research around that time [

71]. While included studies were not required to explicitly use the terms ACEs or PCEs, inclusion was based on predefined conceptual criteria aligned with these frameworks. This allowed for the inclusion of studies addressing related constructs—such as trauma, early adversity, or resilience—when conceptually consistent with the ACE/PCE paradigm. While earlier studies may have examined similar phenomena under different terms, we prioritized capturing developments aligned with the contemporary conceptualization of ACEs that build upon pre-2009 conceptual foundations. This approach ensured terminological flexibility within a coherent temporal and conceptual scope. Research on PCEs, in particular, has gained significant momentum over the past five years, with most relevant studies published during this period [

44,

72]. The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was peer-reviewed by experts in the field to ensure comprehensiveness and accuracy.

4.3. Study/Source of Evidence Selection

All identified citations were collated in Zotero and uploaded into Dedupendote for deduplication, ensuring only unique studies were included in the review. The deduplicated records were then imported into Rayyan, where two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Studies deemed potentially relevant were retrieved in full and subsequently double-screened independently by two reviewers.

During the abstract and full-text screening phases, interrater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa, as recommended by the JBI guidelines for scoping reviews. For the abstract screening (N = 1695), the kappa value was 0.617, indicating substantial agreement between reviewers. For the full-text screening (N = 124), the kappa value was 0.815, reflecting almost perfect agreement [

73]. These levels of agreement ensured a consistent and reliable selection of articles, aligning with the methodological standards for scoping reviews.

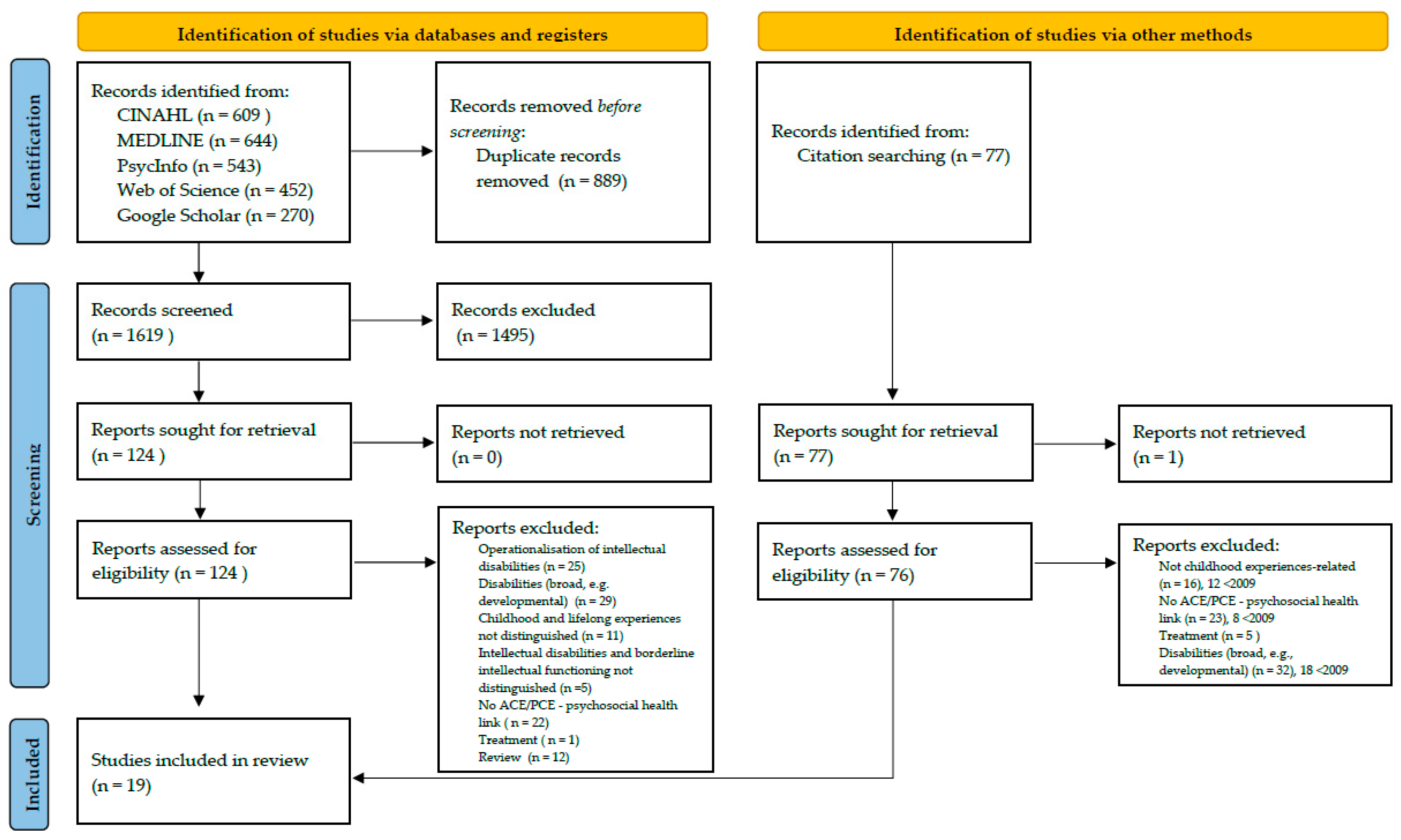

Exclusion reasons for full-text articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were meticulously recorded and are detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram. Key trends in exclusions are summarized in the Results Section for transparency. This approach aligns with JBI recommendations for transparent reporting in scoping reviews. Any disagreements between reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion or by involving a third reviewer, the third author. The results of the search and the study inclusion process are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (see

Figure 1) [

69].

4.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted from the included studies by two independent reviewers using a data extraction tool developed for this review. The extracted data covered population, concept, context, study methods, and key findings relevant to the review questions. To enhance clarity, efficiency, and alignment with the scoping review objectives, the data extraction instrument was refined by streamlining categories, improving methodological detail, and ensuring consistency in capturing key findings. A comprehensive overview of the final data extraction tool is provided in

Supplementary Table S2. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or, when necessary, with the involvement of a third reviewer.

4.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

Extracted data were analyzed using a descriptive qualitative synthesis approach, in line with JBI scoping review guidelines. Full details on the standardized data extraction form, including variables and coding structure, are described in

Section 4.4 and

Supplementary Table S2.

To facilitate comparison across studies, psychosocial outcomes were initially categorized into developmental, behavioral, and mental health domains. However, due to frequent overlap between these domains, outcomes were synthesized under the broader umbrella of psychosocial functioning. Recurring themes and patterns were identified across ecological contexts, including family, school, and community environments. A comparative analysis was conducted to assess variations in conceptualization, measurement, and reported associations among ACEs, PCEs, and psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities.

In line with JBI guidance for scoping reviews, no formal critical appraisal of study quality was conducted. While this approach supports broad mapping of the literature, it limits conclusions about the robustness of individual studies. Future systematic reviews may incorporate critical appraisal to assess the strength and reliability of the evidence base.

5. Results

This section presents the results of the scoping review in relation to two key review questions: (1) how ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs are defined, operationalized, and measured in studies involving children with intellectual disabilities; and (2) what is known about their associations with psychosocial outcomes.

A total of 124 full-text articles were screened, with 19 meeting inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they did not meet population criteria, lacked conceptual alignment with ACE/PCE frameworks, or did not examine psychosocial outcomes.

Findings are structured in three parts: an overview of study characteristics; an analysis of how childhood experiences were conceptualized and measured; and a synthesis of reported associations with psychosocial outcomes. Tables and figures are integrated throughout to support the narrative synthesis.

5.1. Study Characteristics

This section summarizes the characteristics of the 19 included studies, including their designs, demographics, geographic distribution, and data collection methods, to contextualize how ACEs and PCEs have been investigated in children with intellectual disabilities. These characteristics provide the foundation for addressing the review questions, particularly the definitions, operationalization, and measurement of ACEs and PCEs, as well as their relationships with psychosocial outcomes.

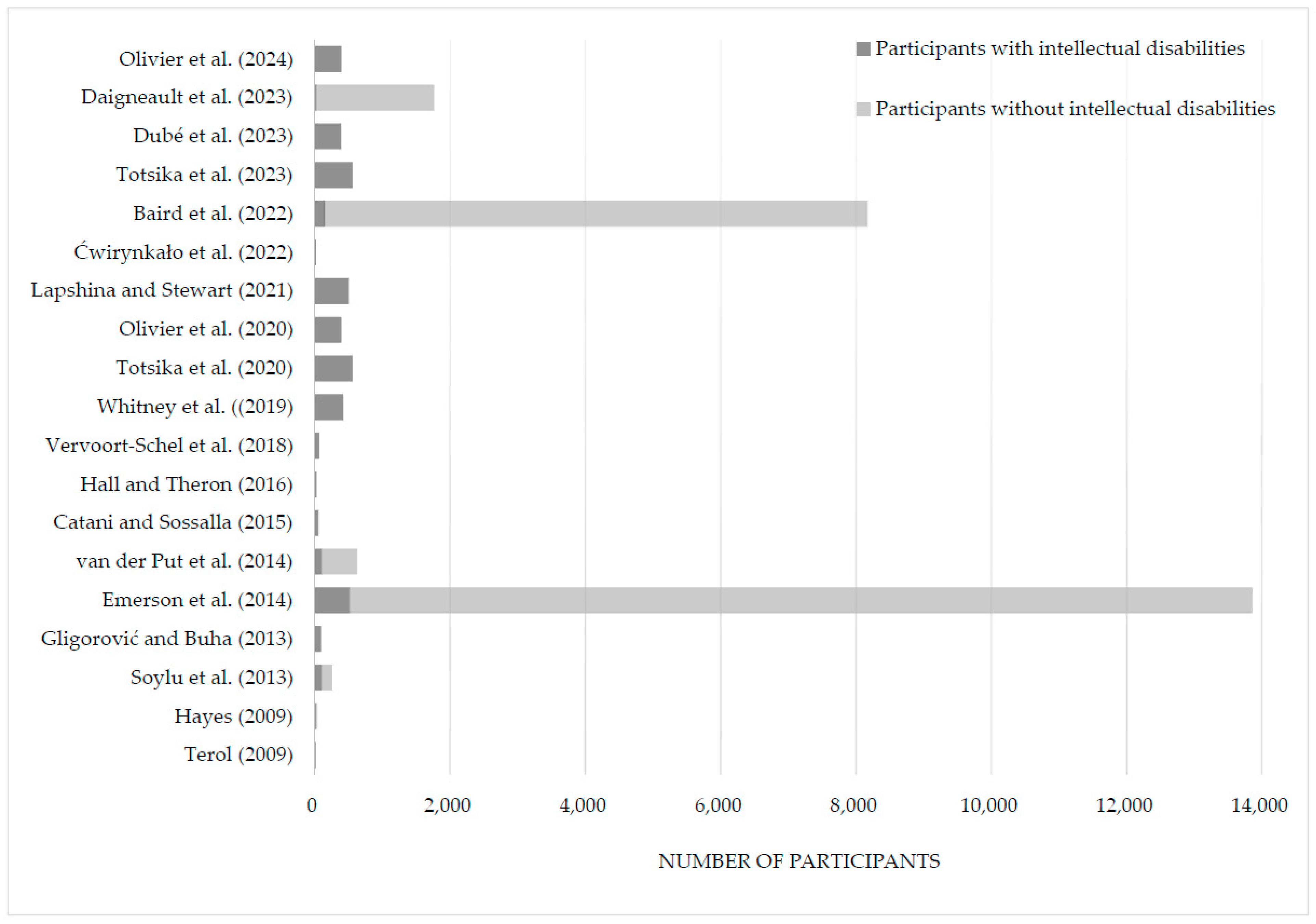

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present visual summaries of these findings.

5.1.1. Study Designs

The included studies employed a diverse range of research designs, reflecting varied approaches to investigating ACEs and PCEs in children with intellectual disabilities. Three studies [

43,

74,

75] used qualitative or mixed methods approaches, providing in-depth insights into lived experiences and contextual influences. Observational methods were most common, with six studies using longitudinal cohort designs [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81] and six using cross-sectional designs [

28,

70,

82,

83,

84,

85]. Three studies utilized retrospective analysis, relying on medical records, parent-reported data, and historical documentation to explore the influence of past events on psychosocial outcomes [

40,

86,

87]. One study [

88] employed a matched cohort design to control for confounders. No experimental or intervention studies were identified, likely reflecting the focus on naturalistic associations rather than intervention outcomes. The distribution and characteristics of study designs are summarized in

Table S5. The influence of study designs on findings is further discussed in

Section 5.2.2.

5.1.2. Demographic and Sample Characteristics

The 19 included studies analyzed a combined sample of 28,205 participants, of whom 4424 (15.7%) were identified as having intellectual disabilities. However, as some studies were derived from overlapping datasets, these figures do not necessarily reflect a fully distinct sample. Four studies analyzed data from the UK’s Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) [

76,

77,

80,

81], while three relied on a sample of secondary school students from Australia and Canada [

78,

79,

84]. Sample sizes varied substantially, ranging from small cohorts of 15 participants to large population-level datasets exceeding 13,000 participants. The proportion of participants with intellectual disabilities within the studies ranged from 1.8% to studies exclusively focused on intellectual disabilities populations, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Participant ages spanned from 9 months to 54 years, with most studies focusing on children and adolescents up to 19 years old, which is consistent with the inclusion criterion of childhood experiences [

40,

70,

74,

75,

76,

77,

80,

81,

83,

85,

86,

87,

88]. In the dataset used for three studies [

78,

79,

84], a negligible proportion of participants up to 22 years of age were included due to the focus on students in special education. However, the average age in this dataset was 15 years, supporting its alignment with the focus on childhood experiences. Studies with older participants typically relied on retrospective data to examine childhood adversities and positive experiences, offering valuable insights into long-term impacts [

28,

43,

82].

Gender data were reported across all studies. However, Emerson et al. [

81] only provided gender-specific analyses of intellectual disabilities prevalence and behavioral outcomes, without reporting the total number of male and female participants in the sample. Apart from the studies that exclusively comprised boys [

43,

82] or girls [

75], the proportion of boys ranged from 24% to 74% in mixed-gender studies, with similar trends observed in studies focusing on intellectual disabilities subgroups. However, detailed gender-specific analyses within the intellectual disabilities population were sometimes limited or inconsistently reported [

80,

81,

88].

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the total sample sizes and the proportion of participants with intellectual disabilities across the included studies. This visualization highlights the variation from mixed samples to studies entirely composed of intellectual disabilities participants and offers context for understanding the demographic scope of the included studies. The influence of gender differences and intellectual disabilities severity on findings is further discussed in

Section 5.2.4 and

Section 5.2.5.

5.1.3. Geographic Distribution of Studies

The included studies spanned countries across Europe, North America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. The United Kingdom had the highest representation with four studies [

76,

77,

80,

81]. Three studies were multinational, encompassing both Canada and Australia [

78,

79,

84]. In addition, Canada was represented by two single-country studies [

86,

88], and Australia by one [

82]. Single studies were also conducted in the United States [

83,

85], the Netherlands [

40], Poland [

43], South Africa [

74], Turkey [

87], the Philippines [

75], Italy [

28], and the Republic of Serbia [

70].

The geographic origins of all studies are summarized in

Table S5. The influence of geographic variability and cultural contexts on findings is further discussed in

Section 5.2.3.

5.1.4. Conceptualization, Operationalization, and Measurement of Childhood Experiences

Across the 19 included studies, ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs were identified and assessed for alignment with established frameworks, as outlined in

Section 3.2. Differences emerged in how these constructs were defined, classified, and operationalized, as well as in the methods used to measure them.

Of the 19 included studies, 9 focused exclusively on ACEs and ACE-/PCE-related constructs [

28,

40,

75,

81,

82,

85,

86,

87,

88]. One study [

74] primarily explored positive childhood experiences and resilience processes in adolescents with intellectual disabilities, while also acknowledging adverse experiences such as poverty, maltreatment, and institutional placement as contextual risk factors. A total of nine studies included both ACEs and PCEs and ACE-/PCE-related constructs [

43,

70,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

83,

84]. However, only one study explicitly used the term ACEs [

40], one referred to potentially traumatic events [

86], and one used adverse life events [

28], while the remaining studies did not employ these terms for the studied adversities. Moreover, none of the included studies explicitly used the term PCEs for the positive childhood experiences in the lives of children with intellectual disabilities.

Table 1 provides an overview of the ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs examined in each study, while

Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 provide details on their operationalization, measurement methods, and associations with psychosocial outcomes.

The operationalization of ACEs encompassed a broad range of adversities, including maltreatment (e.g., physical, emotional, and sexual abuse), neglect (physical, emotional), household dysfunction (e.g., parental mental illness, substance use, incarceration), peer victimization (e.g., bullying, social rejection), and structural adversity such as poverty and material deprivation. Some studies categorized ACEs as discrete events, assessing their presence or absence [

28,

40,

86], while others measured them along a continuum, considering severity, duration, or cumulative exposure [

43,

82,

85].

PCEs were conceptualized as protective relational and environmental protective experiences, including parent–child warmth, peer acceptance, positive school experiences, and community support. While some studies classified PCEs as categorical variables, others assessed variations in their quality, stability, or perceived impact [

77,

78,

79]. During the review process, three constructs, living with families [

70], maternal resources [

81], and nuclear family structure [

80], were initially evaluated differently by the first two authors. Following further discussion and literature review, living with families was included for its established positive impact on child development. Maternal resources was added due to its link to caregiver support and resilience in children with intellectual disabilities, encompassing maternal socioeconomic and caregiving capacity, including education level and single parenthood. Nuclear family structure was included because research (e.g., [

80]) indicates its association with lower conduct problems in children. While PCEs typically emphasize relationship quality over structure, the presence of both biological parents often provides stability, consistency, and protective effects, aligning with the broader concept of positive childhood experiences.

Measurement approaches varied depending on the construct and study design. ACEs were commonly assessed using standardized instruments, such as the interRAI Child and Youth Mental Health-DD (ChYMH-DD) for polyvictimization [

86] and the 22-item ACE checklist adapted for children with intellectual disabilities [

28]. In addition to these structured tools, some studies employed case-file analyses with predefined coding frameworks [

40,

88] or relied on administrative records to capture socioeconomic adversity and family structure [

80,

83]. PCEs were frequently assessed using validated scales, such as a 6-item subscale for parent–child warmth [

78] and the Child-Parent Relationship Scale [

77]. While structured instruments were common, some studies relied on observational or qualitative methods, such as draw-and-talk methodology, interpretative phenomenological analysis, and thematic analysis, to explore lived experiences related to family dynamics, resilience, and adversity [

28,

43].

Differences in measurement approaches were also evident across contexts. Family-based ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs were predominantly assessed through caregiver reports, reflecting parental perspectives on adverse and positive childhood experiences [

77]. In contrast, school and community factors were more frequently examined using observational and qualitative methods, allowing for a contextualized understanding of social dynamics and support structures [

43,

74]. Environmental adversities, such as poverty and neighborhood deprivation, were typically assessed using administrative data, which provided objective indicators of structural risk factors [

80,

83]. Interpersonal adversities, including maltreatment, neglect, and household dysfunction, were primarily captured through self- or caregiver-reported measures, emphasizing individual experiences of adversity [

28,

43,

77]. Some studies combined structured assessments with official records to classify ACEs and PCEs, ensuring a standardized evaluation of these constructs [

85,

86].

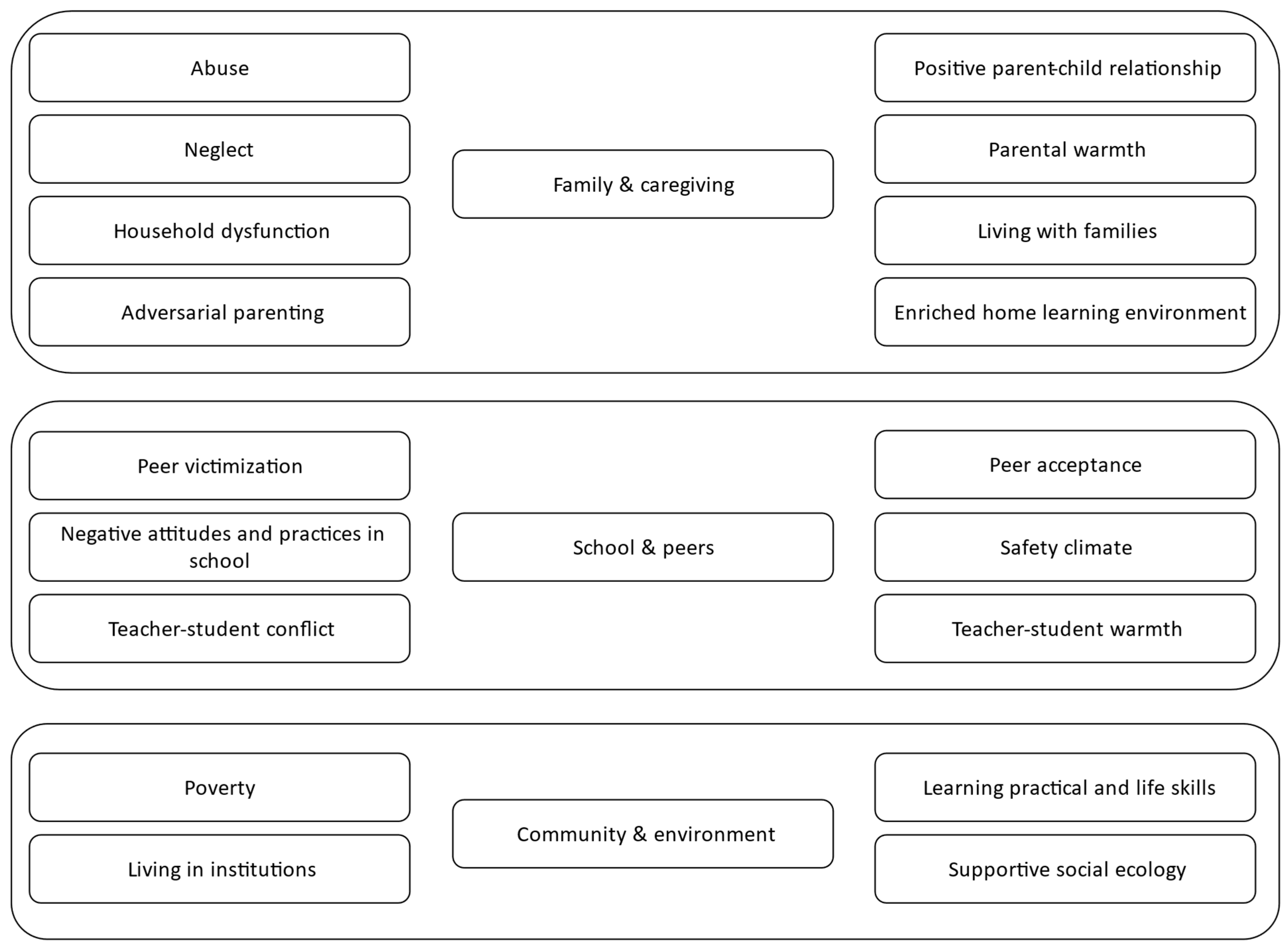

The considerable variability in how ACEs and PCEs were conceptualized and measured across studies underscores the complexity of comparing findings and identifying consistent patterns. To illustrate the interconnectedness of these constructs,

Figure 3 presents a clustered overview of ACEs and PCEs across three ecological domains: family and caregiving, school and peers, and community and environment. This categorization is informed by a thematic organization of the identified constructs, illustrating how adverse and positive childhood experiences interact across social contexts, shaping psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. The following section examines the extent to which these constructs are associated with psychosocial outcomes, focusing on cumulative risk and resilience processes.

5.2. Associations Among ACEs, PCEs, and Psychosocial Outcomes

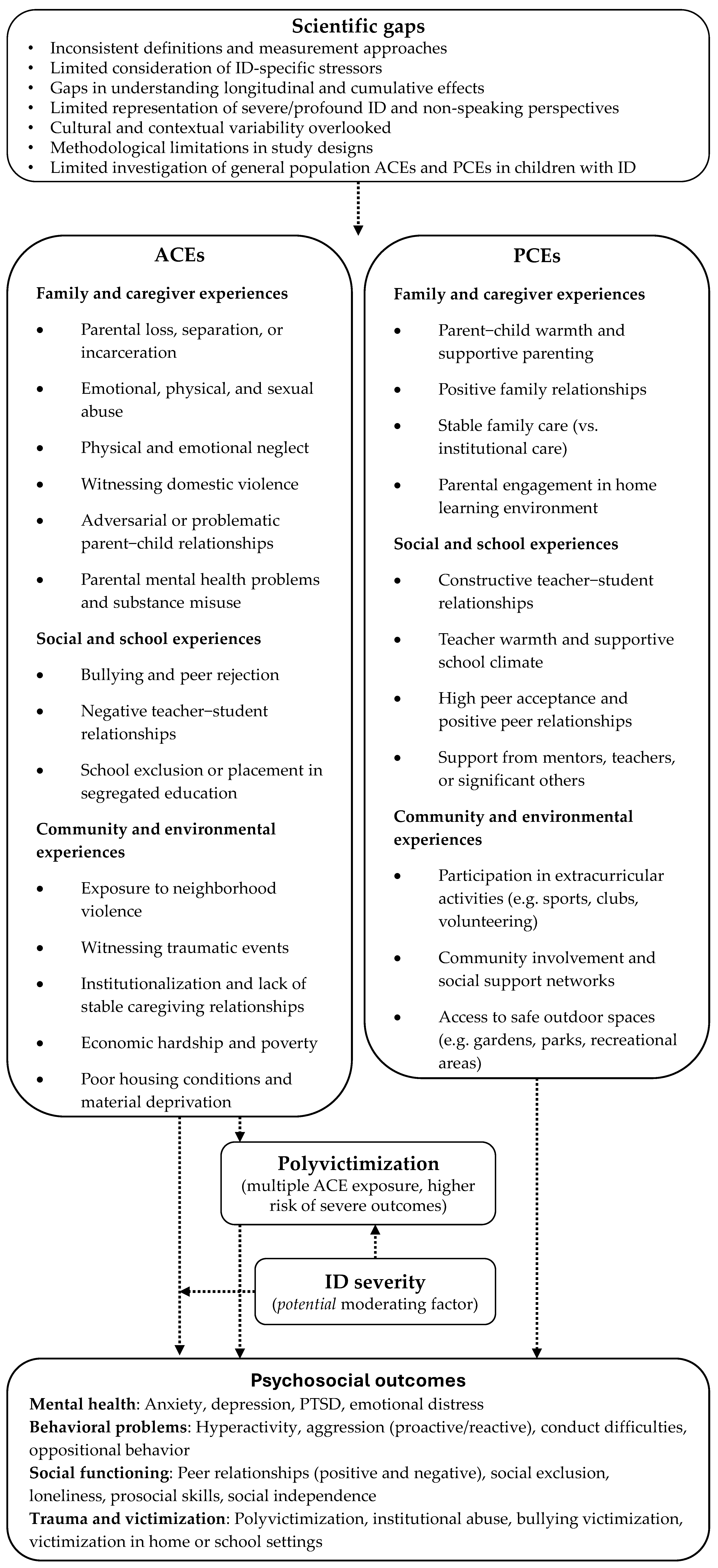

This section outlines the key findings on ACEs, PCEs, ACE-/PCE-related constructs, and psychosocial outcomes. The subsequent sections examine the influence of study design, geographic and cultural variability, gender differences, and intellectual disabilities severity. The findings are synthesized in

Figure 4, which provides a conceptual model of these associations.

5.2.1. Key Findings on ACEs, PCEs, and Psychosocial Outcomes

Across the 19 included studies, children with intellectual disabilities were found to be disproportionately exposed to a broad range of ACEs. These adversities spanned family-related challenges (e.g., emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; witnessing domestic violence; parental substance misuse or mental health problems), school-related stressors (e.g., peer victimization, teacher–student conflict), and broader socio-environmental hardships (e.g., household poverty, neighborhood disadvantage, and substandard living conditions). Exposure to ACEs was consistently associated with increased risks of emotional, behavioral, and social difficulties, although the specific severity and nature of these outcomes varied across studies (see

Table S5 for an overview of study characteristics and reported associations among ACEs, PCEs, and psychosocial outcomes).

Several studies indicated that the accumulation of ACEs, rather than individual ACE subtypes, was a key predictor of psychosocial difficulties [

40,

77,

81,

85,

86]. Polyvictimization—experiencing multiple ACEs—was particularly associated with higher risks of persistent behavioral problems (e.g., conduct difficulties, hyperactivity, aggression), emotional distress (e.g., anxiety, depressive symptoms, trauma-related distress), and social or adaptive impairments (e.g., reduced social skills, difficulties in parent–child or school relationships). Lapshina et al. [

86] found that children with intellectual disabilities who had experienced three or more ACEs exhibited significantly higher levels of proactive and reactive aggression. Their study also highlighted interrelationships between different forms of adversity, such as physical abuse, emotional abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and parental substance abuse. Similarly, Van der Put et al. [

85] reported that juvenile offenders with intellectual disabilities who had experienced multiple types of maltreatment exhibited greater risks of both violent and non-violent offending, with particularly strong associations between sexual and physical abuse and later sexual offending. In a residential care setting, Vervoort-Schel et al. [

40] observed that higher cumulative ACE exposure was associated with increased trauma-related symptoms and attachment difficulties.

Although polyvictimization emerged as a central risk factor, some studies reported distinct effects of specific ACE subtypes. Emotional abuse and neglect were associated with higher risks of PTSD and depression, though findings varied depending on study populations and measurement approaches [

28,

40]. Institutional abuse was reported in specific subgroups, with a prevalence of 80.4% in one study examining institutionalized individuals with intellectual disabilities [

28]. However, familial abuse was more strongly associated with PTSD symptoms than institutional abuse alone in the populations studied.

The high prevalence of ACEs among children with intellectual disabilities was documented across multiple studies. Vervoort-Schel et al. [

40] reported that 82.6% of children in residential care had experienced at least one ACE, with nearly half (49.3%) exposed to two or more ACEs. Similarly, Lapshina et al. [

86] found that children with intellectual disabilities frequently experienced multiple adversities, reinforcing the pattern of disproportionate ACE exposure in children with intellectual disabilities.

Beyond individual adversities, socioeconomic factors were found to play a significant role in shaping ACE exposure and psychosocial difficulties. Emerson et al. [

81] reported that cumulative environmental stressors, including household poverty and parental distress, were strongly associated with behavioral difficulties in children with intellectual disabilities. Additionally, Baird et al. [

80] and Totsika et al. [

77] identified associations between poor housing conditions, neighborhood disadvantage, and increased behavioral dysregulation in children with intellectual disabilities.

Several studies examined the potential protective effects of PCEs. Totsika et al. [

77] and Olivier et al. [

84] reported that positive caregiving relationships and school-based support were associated with lower anxiety levels, reduced behavioral difficulties, and improved social functioning. Totsika et al. [

77] found that warm and supportive parent–child relationships were consistently linked to lower conduct problems and improved self-regulation, particularly in contexts of socioeconomic adversity. Furthermore, a more enriched home learning environment was associated with better social well-being, including enhanced prosocial skills and independence [

77]. However, the effects of a highly structured home environment were mixed, as some findings indicated a negative association with social well-being, potentially related to reduced social flexibility in structured settings.

5.2.2. Variation in Findings by Study Design

The methodological approaches used in the included studies were reflected in the type and depth of the reported findings. Longitudinal studies [

77,

80,

81] provided insights into the developmental trajectories of children with intellectual disabilities, showing how ACEs and PCEs were associated with psychosocial outcomes over time. These studies found that early exposure to multiple ACEs was linked to higher rates of emotional and behavioral difficulties over time, particularly conduct problems and externalizing behaviors [

77,

81,

86]. While structured home environments were associated with some improvements in social functioning, these effects varied depending on contextual factors such as socioeconomic adversity [

76]. Additionally, positive school experiences, particularly supportive teacher–student relationships, were linked to reduced anxiety and depression [

78,

79]. However, differences in measurement tools and exposure timeframes across studies made direct comparisons challenging.

In cross-sectional studies [

83,

84,

85], significant associations were found between ACEs and behavioral outcomes. Whitney et al. [

83] identified peer victimization as a significant factor associated with increased anxiety and depression in children with intellectual disabilities. Similarly, Olivier et al. [

84] reported that peer victimization was linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms, particularly when protective teacher–student relationships were absent. However, these studies focused on associations and did not assess the directionality of these relationships.

Retrospective studies investigating the long-term consequences of ACEs provide evidence for the cumulative risk model [

70,

80,

83]. Higher exposure to ACEs was associated with increased likelihoods of trauma-related disorders and externalizing behaviors. However, methodological limitations, such as reliance on self-reported recall and inconsistencies in secondary data sources, are noted. These limitations may affect the accuracy and reliability of the reported experiences.

Finally, qualitative and mixed methods studies, such as those by Ćwirynkało et al. [

43] and Hall and Theron [

74], provided contextual insights into resilience and coping mechanisms, emphasizing the role of social support networks, cultural influences, and adaptive coping strategies. Ćwirynkało et al. [

43] found that fathers with intellectual disabilities who had experienced childhood adversities often used these experiences to strengthen their own parenting strategies, while Hall and Theron [

74] highlighted the importance of informal and formal support systems, such as teachers and family, in fostering resilience among adolescents with intellectual disabilities in a South African context. While these studies contributed valuable depth to understanding positive childhood experiences, their small sample sizes and cultural specificity may limit generalizability.

5.2.3. Geographic Variability and Cultural Contexts

The studies included in this review spanned diverse geographic regions, covering high-income countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

84,

86], as well as middle- and low-income regions, including South Africa and the Philippines [

74,

75]. Studies from high-income countries examined the role of family support, peer relationships, and school climate in shaping psychosocial outcomes for children with intellectual disabilities. For example, in Canada and Australia, school climate and the quality of teacher–student relationships were identified as important factors associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms among youth with intellectual disabilities [

78,

79]. Additionally, peer victimization was found to be associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in these contexts [

84]. Studies in these high-income countries also highlighted the role of family poverty in influencing children’s behavioral and emotional outcomes [

77].

In middle- and low-income regions, such as South Africa and the Philippines [

74,

75], poverty and systemic resource limitations were reported to exacerbate psychosocial risks, with limited access to resources and lack of support systems being critical factors that impacted children with intellectual disabilities in these regions.

While these studies offer insights into region-specific challenges, no systematic cultural comparisons can be derived from the available data.

5.2.4. Gender Differences

Findings on gender differences in psychosocial outcomes among children with intellectual disabilities were mixed and inconsistent. Several studies suggested that boys with intellectual disabilities exhibited more externalizing behaviors and persistent conduct problems than girls (e.g., aggression, hyperactivity, conduct disorder) [

80,

81,

86]. Some studies indicated higher rates of internalizing disorders, such as depression, among girls with intellectual disabilities [

79,

87]. However, other studies found no significant gender differences in outcomes such as anxiety, PTSD, or overall mental health after adjusting for relevant factors [

40,

83,

85]. In many cases, gender-specific analyses within the intellectual disabilities population were either absent or inconclusive.

5.2.5. Severity of Intellectual Disabilities as Factor in Psychosocial Outcomes

ACE Exposure and Intellectual Disabilities Severity

Several studies examined the relationship between intellectual disabilities severity and exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Lapshina and Stewart [

86] found that children with mild or moderate intellectual disabilities reported higher exposure to ACEs, including polyvictimization, compared to children with severe or profound intellectual disabilities. This discrepancy was attributed to differences in communicative and cognitive abilities, which may affect how adversity is perceived, recalled, and reported. Emerson et al. [

81] reported that children with mild intellectual disabilities were more frequently exposed to environmental risk factors such as poverty and parental psychological distress. Similarly, Totsika et al. [

77] observed that early exposure to poverty and parental distress was associated with later adversity, particularly among children with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.

Psychosocial Outcomes by Severity Level

Differences in psychosocial outcomes were also reported in relation to intellectual disabilities severity. Lapshina and Stewart [

86] found that children with mild or moderate intellectual disabilities were more likely to display externalizing behaviors, such as proactive and reactive aggression. Whitney et al. [

83] reported higher levels of behavioral problems among children with mild intellectual disabilities, although no consistent associations were found between intellectual disabilities severity and internalizing outcomes such as anxiety or depression.

Dubé et al. [

79] found no significant association between intellectual disabilities severity and overall anxiety trajectories in school settings. However, they noted that changes in teacher–student relational climate were linked to momentary increases in anxiety across the sample. Olivier et al. [

84] reported that conflictual teacher–student relationships were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, particularly among children with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.

Interaction with Environmental Factors

In a study by Baird et al. [

80], the relationship between household spatial density and conduct problems differed by intellectual disabilities severity. While higher spatial density was associated with more conduct problems in the general population, children with intellectual disabilities—particularly those with more severe presentations—showed fewer reported conduct problems in crowded households. The authors hypothesized that closer proximity to caregivers or siblings might offer protective effects in these contexts, although these findings remain preliminary and warrant further investigation.

Overall, the reviewed studies suggest that the severity of intellectual disability may influence both the extent of ACE exposure and the nature of psychosocial outcomes. Children with mild intellectual disabilities appear more likely to experience multiple adversities (e.g., polyvictimization) and show higher rates of behavioral and emotional difficulties, while children with severe or profound intellectual disabilities are often underrepresented or may face challenges in reporting such experiences. These differences may reflect not only variation in actual exposure but also disparities in how adversity is perceived, recognized, or reported—particularly among those with more severe cognitive and communicative limitations.

Figure 4 presents a schematic representation of patterns reported across the included studies, illustrating how ACEs, PCEs, related constructs, polyvictimization, intellectual disabilities severity, and psychosocial outcomes have been described in relation to one another. The figure does not imply causality and uses dotted arrows throughout to indicate that all depicted relationships are tentative and based on exploratory evidence. This visual approach reflects the descriptive and hypothesis-generating nature of the review.

Polyvictimization is tentatively represented as a possible mechanism linking cumulative exposure to adversity with elevated psychosocial risk. Intellectual disabilities severity is likewise depicted as a potential moderating factor, based on indications that it may influence both exposure and psychosocial outcomes, although findings were limited and inconsistent.

The figure serves as a descriptive synthesis of the reviewed literature and a starting point for future hypothesis-driven research. Key gaps include the limited empirical attention to protective experiences (PCEs), the lack of studies examining interactions between ACEs and PCEs, and the absence of longitudinal evidence to support potential feedback loops from psychosocial outcomes to earlier risk or protective exposures.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

This scoping review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the existing literature on ACEs, PCEs, and ACE-/PCE-related constructs, and their associations with psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. The findings indicate that ACEs occur across multiple ecological contexts—including family, school, and community settings—and are significantly associated with adverse psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. However, there was notable variability in how ACEs were defined and measured across studies, with some incorporating broader structural adversities such as institutionalization [

40,

70,

86] and socioeconomic hardship [

76,

77,

81], while others focused on interpersonal experiences of abuse and neglect [

28,

75,

86,

87,

88]. Notably, the terms “ACEs” and “PCEs” were rarely used explicitly; instead, studies relied on conceptually related or overlapping constructs. These inconsistencies are further discussed in

Section 6.3.1.

Polyvictimization—the cumulative exposure to multiple ACEs—was consistently associated with greater psychosocial difficulties, particularly externalizing behaviors such as aggression and conduct problems, which were more frequently reported in children with mild intellectual disabilities [

40,

81,

85,

86]. In contrast, children with severe intellectual disabilities were less frequently identified as experiencing multiple ACEs, but this discrepancy may reflect methodological and assessment-related challenges rather than genuinely lower exposure rates [

86]. Limited verbal communication and reliance on caregivers for reporting—combined with the inability of many individuals with severe or profound intellectual disabilities to self-report—may contribute to an underestimation of adversity in this subgroup. Similar patterns have been observed in the general population, where polyvictimization is linked to heightened risks of externalizing and internalizing psychopathology, with effects accumulating over time [

89]. Moreover, research indicates that children with communication difficulties, regardless of disability status, may be underrepresented in trauma studies due to methodological barriers [

90]. As discussed in

Section 6.3.4, children with severe and profound intellectual disabilities remain underrepresented in research, highlighting the need for improved assessment methods to capture their lived experiences more accurately.

Findings regarding gender differences in psychosocial outcomes were inconsistent and analytically underdeveloped across studies. Some research identified gender-based variations—such as higher conduct problem scores among boys [

80] and increased rates of major depressive disorder among girls [

87]—while other studies found no significant differences in trauma exposure [

28,

86], conduct problems [

81,

85], or psychiatric disorders [

40,

78,

83]. Due to heterogeneity in study designs, sample composition, and analytic strategies, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding gender effects in children with intellectual disabilities (see

Section 6.3.6). This pattern is consistent with general population research, where boys more often exhibit externalizing behaviors and girls internalizing symptoms following ACE exposure [

91], but its applicability to children with intellectual disabilities remains unclear and requires further investigation.

Most included studies were conducted in high-income Western countries, with comparatively fewer studies examining ACEs and PCEs in children with intellectual disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. These geographic disparities highlight the need to explore how ACEs and PCEs manifest across different socio-cultural contexts, particularly as conceptual frameworks for children with intellectual disabilities are still in development. However, as discussed in

Section 6.3.5, the current evidence base does not allow for systematic cultural comparisons, and interpretations regarding the role of culture should therefore be made with caution. This is consistent with broader trends in the ACE–PCE literature, where low- and middle-income regions remain underrepresented [

89]. This gap underscores the need for cross-cultural research that accounts for differences in how adversity and resilience are conceptualized and measured [

90].

Section 6.3.5 further explores the challenges of applying existing ACE-PCE frameworks across diverse cultural contexts.

Children with severe intellectual disabilities had reduced access to positive school experiences, such as supportive teacher–student relationships, positive peer interactions, and an inclusive school environment, which may further increase their vulnerability to adverse psychosocial outcomes [

79,

84]. Additionally, ACEs in children with intellectual disabilities may extend beyond traditional categories, encompassing experiences such as peer victimization [

78,

84], institutional abuse [

28], and parental psychological distress [

76,

77]. Additionally, ACEs for children with intellectual disabilities may include parental abandonment [

86] and family verbal conflict, which has been linked to increased suicidality in individuals with intellectual disabilities [

82]. Furthermore, harsh or inconsistent parenting [

81] and environmental stressors such as living in a violent neighborhood [

86] or experiencing multiple placements in residential care [

40] contribute to the accumulation of adversity. While these factors have been examined in relation to behavioral trajectories, further research is needed to clarify their direct psychosocial impact and how they interact with intellectual disabilities-specific vulnerabilities. This aligns with broader research on adversity and resilience, reinforcing that children with intellectual disabilities experience unique vulnerabilities due to cognitive, social, and environmental factors [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

PCEs—including positive teacher–student relationships [

77,

79], inclusive school climates [

79], warm and supportive parent–child relationships [

77,

78], and community-based support networks [

74]—were found to buffer some of the negative effects of ACEs. However, their protective impact was context-dependent. The presence of relational or environmental stressors—such as peer victimization [

78,

83], student–teacher conflict [

84], or socioeconomic hardship [

77,

92]—diminished the mitigating effects of PCEs. This reinforces the understanding that PCEs do not operate in isolation but interact with broader social and environmental contexts, shaping their protective impact [

93,

94]. These findings underscore that PCEs should not be viewed as universally protective but as part of a dynamic and context-sensitive interplay among individual, relational, and structural factors. These complexities in how PCEs function across different environments—and the need for more refined conceptual models—are further explored in

Section 6.3.1 and

Section 6.3.3.

Taken together, the findings highlight the wide range of adverse and protective experiences reported across family, school, and community settings, as well as the conceptual and methodological variation in how these experiences have been defined and assessed in children with intellectual disabilities. While this review highlights emerging patterns—such as the relevance of polyvictimization, the context-dependent function of PCEs, and the role of intellectual disabilities severity—it also reveals important conceptual and methodological limitations that constrain synthesis and limit theoretical development. The next sections discuss these knowledge gaps, study limitations, and implications for future research and practice.

6.2. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this review lies in its systematic and transparent approach to synthesizing evidence on ACEs, PCEs, and related constructs in relation to psychosocial outcomes in children with intellectual disabilities. By integrating findings across diverse geographic contexts and study designs, the review offers a structured overview of how adverse and protective experiences—whether explicitly labeled or conceptually related to ACEs and PCEs—have been studied in this population. This includes attention to ecological variation and a broad conceptualization of adversity, encompassing not only interpersonal maltreatment but also structural, environmental, and institutional stressors. Despite these strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged—both in the included studies and in the review process itself.

First, the conceptual and operational definitions of ACEs and PCEs varied considerably across studies. Some focused narrowly on abuse and neglect, while others included broader adversities such as poverty, school exclusion, or parental psychological distress. This heterogeneity complicates synthesis and underscores the need for standardized, intellectual disabilities-sensitive conceptual and measurement frameworks (see also

Section 6.3.1).

Second, publication bias may have affected the evidence base. By including only peer-reviewed articles indexed in English-language databases, studies from non-English-speaking regions may have been missed. Although gray literature was used for citation tracking, it was not included in the synthesis. This may have led to overrepresentation of studies reporting statistically significant findings.

Third, methodological constraints in the primary studies limit the interpretability of the findings. Most relied on retrospective caregiver reports, with limited use of multi-informant or observational methods—particularly for children with severe or profound intellectual disabilities. These children were often underrepresented, and their experiences may be underestimated due to communication barriers and diagnostic overshadowing (see also

Section 6.3.4).

In addition, this review is subject to limitations inherent to the scoping review methodology. In line with JBI guidance, no formal quality appraisal was conducted, and no effect sizes were synthesized. The schematic representation presented in

Figure 4 is descriptive rather than inferential and should not be interpreted as an empirically validated model. While some included studies explored associations or indirect pathways, theoretical constructs such as moderation by intellectual disabilities severity, interactions between ACEs and PCEs, or feedback loops from psychosocial outcomes were generally not examined through formal statistical modeling. The framework should therefore be seen as a hypothesis-generating synthesis of observed patterns.

Despite these limitations, this review provides an initial foundation for advancing ACE–PCE research in children with intellectual disabilities. By identifying key gaps and conceptual inconsistencies, it supports the development of more inclusive, resilience-oriented research agendas and lays the groundwork for future frameworks that can inform trauma-informed care, intervention, and policy.

6.3. Gaps in Knowledge and Future Directions

6.3.1. Inconsistent Definitions and Measurement Approaches

A consistent limitation across the included studies was the lack of conceptual and operational clarity in defining and measuring ACEs, PCEs, and related constructs. Although these frameworks are increasingly influential in research on childhood adversity and resilience, few studies explicitly employed the terms “ACEs” or “PCEs”. Instead, most used conceptually overlapping or related constructs, reflecting broader definitional variability in the field. This heterogeneity complicates synthesis and limits comparability between studies. Despite the relevance of resilience theory for integrating risk and protection, such frameworks were seldom applied, limiting comparability and synthesis.

Such variability is not unique to research involving children with intellectual disabilities. In the general population, ACE and PCE frameworks remain under refinement, with ongoing debate about their scope and theoretical foundations [

95,

96]. Early models (e.g., Felitti et al. [

7]) emphasized interpersonal forms of abuse and neglect, whereas more recent perspectives advocate for a broader understanding of adversity, incorporating chronic stressors and structural inequities [

46]. Yet, across both general and intellectual disabilities-specific research, inconsistencies remain regarding how to operationalize these experiences—particularly in capturing systemic and environmental adversity.

Among the included studies, definitions of ACEs ranged from narrowly focused interpersonal experiences—such as abuse and neglect—to broader structural and environmental adversities, including institutionalization and socioeconomic hardship [

40,

80,

81]. Similarly, PCEs were conceptualized along a continuum from dyadic relationships (e.g., caregiver warmth, teacher–child interactions) to broader ecological supports, such as inclusive school climates and stable home environments [

74,

76,

79]. This conceptual heterogeneity mirrors broader trends in resilience research, where definitions of PCEs vary from narrowly defined individual traits to ecological frameworks encompassing family, school, and community contexts [

47,

48,

97]. Raghavan and Griffin [

44] emphasize that resilience in children with intellectual disabilities is shaped by the interaction of risk and protective factors across multiple ecological levels. Despite the relevance of such frameworks, few of the included studies explicitly adopted integrative models or applied consistent operational definitions, limiting the comparability and cumulative potential of findings.

The conceptual boundaries among ACEs, PCEs, and related constructs are further complicated by their fluid and dynamic nature. Rather than existing as discrete categories, these experiences likely function along a continuum, where the impact of adversity is shaped by cognitive processing abilities and contextual factors [

22,

46]. This is particularly relevant for individuals with intellectual disabilities, who may experience heightened psychological vulnerability due to difficulties in contextualizing events. This perspective aligns with the model proposed by Kalmakis and Chandler [

46], which conceptualizes adversity not as isolated events, but as cumulative and context-dependent processes embedded in relational, familial, and environmental contexts.

In addition to definitional inconsistencies, measurement strategies varied widely. Most studies relied on retrospective caregiver reports, while fewer used validated tools or multi-informant methods. Intellectual disabilities-specific stressors—such as communication barriers, dependency on caregivers, or institutional settings—were rarely captured in standard ACE measures, raising concerns about construct validity and underestimation of adversity in this population. This is especially relevant for understanding polyvictimization, which was associated with poorer psychosocial outcomes but inconsistently measured (see

Section 6.3.6).

These gaps currently limit the empirical validation of integrative approaches, including the preliminary schematic representation shown in

Figure 4. Without improved standardization in definitions and measurement, it remains challenging to test how ACEs and PCEs may operate across ecological levels or interact with intellectual disabilities-specific vulnerabilities.

To advance the field, future research should prioritize the development of standardized, intellectual disabilities-sensitive operational definitions and measurement tools. These should incorporate both child and caregiver perspectives, allow for non-verbal communication modes, and reflect a broad ecological model of risk and protection. A multi-method, two-generational approach—including direct assessment, structured observation, and administrative data—may strengthen validity and enable a more accurate understanding of adversity and resilience in children with intellectual disabilities. These efforts should be guided by resilience-oriented frameworks that conceptualize adversity and protection as interactive, cumulative, and contextually embedded processes.

6.3.2. Limited Consideration of Intellectual Disabilities-Specific Stressors

Beyond challenges associated with defining and measuring ACEs and PCEs, children with intellectual disabilities face additional, Intellectual disabilities-specific stressors that can complicate the identification and assessment of these constructs. Mechanisms such as diagnostic overshadowing [

40,

83], communication barriers [

78,

82,

87], limited adaptive functioning [

98], and long-term dependency on caregivers [

99] can significantly shape both the recognition of ACEs and the access to PCEs. Traditional ACE and PCE frameworks do not fully account for these unique vulnerabilities, leading to inconsistencies that obscure the complex interplay between adversity and resilience in children with intellectual disabilities.

A broader examination of the literature screened for this review suggests that several institutional, medical, and psychosocial stressors remain underexplored in relation to psychosocial outcomes for children with intellectual disabilities. These stressors—such as restraint and seclusion [

100], medical complexity or complications [

101,

102,

103,

104], caregiver burden [

105,

106,

107], challenges in educational participation and school transitions [

108,

109,

110], and stigma [

111,

112,

113,

114]—highlight critical areas for future research.

As discussed in

Section 6.3.6, improvements in assessment methodology are essential for capturing such experiences more comprehensively. In particular, the development of an intellectual disabilities-specific, two-generational ACE–PCE screening tool—one that accommodates communication barriers and integrates alternative reporting formats—would enhance both the accuracy and inclusivity of adversity assessment in this group. Such tools should be grounded in an ecological perspective, capturing adversity and protective experiences across individual, familial, educational, healthcare, and community settings—while accounting for the communicative, cognitive, and contextual characteristics of children with intellectual disabilities.

6.3.3. Gaps in Understanding Longitudinal and Cumulative Effects

Although some longitudinal studies have provided valuable insights into developmental trajectories and cumulative risk exposure [

77,

80,

81], research remains limited in scope and does not sufficiently capture long-term psychosocial outcomes or explore the potential role of mediating and moderating mechanisms in shaping resilience trajectories. Most studies rely on cross-sectional or retrospective designs, restricting causal interpretation and obscuring potential bidirectional effects among adversity, resilience, and mental health.

The framework in

Figure 4 highlights polyvictimization as a pathway through which multiple ACEs contribute to psychosocial difficulties. However, longitudinal studies typically focus on specific developmental stages—often early childhood or adolescence—and rarely follow individuals into adulthood. Although some evidence suggests that PCEs buffer against ACEs [

48], little is known about their timing, duration, or stability over time [

115,

116], particularly in children with intellectual disabilities.

Furthermore, the intergenerational transmission of adversity and resilience remains an overlooked area. While parental psychological distress and socioeconomic hardship have been identified as key ACE-related risk factors [

76,

77], there is little research examining how these adversities persist or are mitigated across generations in families of children with intellectual disabilities. Understanding these dynamics would refine theoretical models and inform the timing of interventions to maximize protective outcomes.

Age was seldom analyzed as a moderator of ACE or PCE effects. Although gender was more frequently included in subgroup analyses, the influence of developmental stage remains unclear—despite theoretical support for the importance of timing in psychosocial outcomes [

117]. Future work should examine how ACEs and PCEs interact with age-specific vulnerabilities and resources across varied developmental profiles in children with intellectual disabilities.

Well-powered longitudinal studies are needed to track children with intellectual disabilities across life stages, assess how cumulative ACE exposure interacts with intellectual disabilities-specific vulnerabilities, and determine whether PCEs offer sustained protection. Research should also explore ACE–PCE interactions within unified analytical models and examine feedback loops from psychosocial outcomes to earlier exposures. As noted in

Section 6.3.6, methodologically rigorous, multi-informant, and ecologically valid designs are essential for testing dynamic, resilience-oriented frameworks in this population.

6.3.4. Insufficient Representation of Children with Severe and Profound Intellectual Disabilities

Across the reviewed studies, children with severe and profound intellectual disabilities were markedly underrepresented, with most research focusing on individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities [

78,

79,

86]. Consequently, the ways in which ACEs and PCEs manifest in this subgroup and their potential impact on psychosocial outcomes remain underexplored [

52]. This gap is especially concerning given the distinct vulnerabilities these children face—such as limited expressive communication, reduced self-advocacy, and long-term dependence on caregivers and services [

78,

98,

118].

While caregiver reports provide valuable insight into a child’s experiences, they may not fully capture internalized distress, trauma-related symptoms, and social–emotional difficulties, particularly in children with severe and profound intellectual disabilities [

78,

86]. Given the limitations of external reporting, alternative methodologies tailored to non-verbal or minimally verbal children may be needed to ensure a more accurate representation of their experiences. The limited use of direct assessments and communication-adapted methodologies further contributes to diagnostic overshadowing [

119] and may reduce opportunities for appropriate intervention [

86].

To address this, future research should employ multi-method strategies—such as observational tools, clinician interviews, and communication-adapted instruments—tailored to the sensory and cognitive profiles of children with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. While such innovation can reduce exclusion, it must be acknowledged that for many non-speaking children, first-person perspectives remain inaccessible. This underscores the need for ethical proxy approaches that respect the child’s autonomy while drawing on caregiver insights and ecologically valid observations.

As discussed in