1. Introduction

Experiences of engaging in activities and participation are for people with disabilities significantly influenced by how well the surrounding community is designed to meet their needs and conditions [

1,

2,

3]. Individuals with disabilities in Sweden, including those with intellectual disabilities, are entitled to the necessary support to ensure equal opportunities, take part in decision-making, and fully participate as citizens in society [

4,

5]. Persons with intellectual disability [

6] in Sweden are entitled to support enabling them to “live like others”, as laid down in

Section 5 of the Act on Support and Services for Persons with Disabilities (Swedish acronym: LSS) [

7]. The United Nation Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) [

5] was ratified by Sweden in 2008 and entered into force in 2009. Sweden’s disability policy [

8] is based on the UNCRPD to achieve equality in living conditions and full participation of persons with disabilities in a diverse society. Despite these rights, research indicates that persons with intellectual disability often struggle to live the life they desire [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Autonomy is a human right and can be defined as behaviors that are consistent with one’s self and are based on one’s volition [

14,

15]. Wehmeyer includes independence in the definition of autonomy and describes that autonomy is present “if the person acts (a) according to his or her own preferences, interests, and/or abilities and (b) independently, free from undue external influence or interference” [

16] (p. 632) However, no person is truly autonomous, as everyone depends on interactions with other people in daily life [

17].

Achieving an adult social status (encompassing control of one’s life, personal safety, and social belonging) is a prerequisite for a good quality of life, according to persons with intellectual disability [

18]. However, the ability to assume responsibility and make decisions may be questioned by others, undermining their sense of such status [

19] and of participation [

20]. The support should be designed based on each person’s own needs [

21]. It may include support in everyday life in the person’s home, work at a daily-activity center, and accompaniment to activities outside the home. Furthermore, persons with intellectual disability have the right to decide how their support should be organized. This is in line with Article 19 UNCRPD, which lays down that people with disabilities have the right to be free and exercise power over their lives, for instance, by making support and assistance choices enabling them to live on an equal basis with others [

5].

However, despite the good intentions of laws and conventions on the rights of persons with intellectual disability, both scientific and government reports indicate that it may be difficult for persons with intellectual disability [

6] in Sweden to obtain support in line with their own wishes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The Swedish Agency for Participation states that persons with intellectual disability have limited participation and choices in life and acknowledges the fact that despite being a heterogenous group, many with intellectual disability live similar lives, probably due to support not being individually tailored [

10]. The National Board of Health and Welfare in 2021 acknowledged restricting and coercive measures in LSS-housings and pointed out a range of aspects in need of improvement such as competency in staff, leadership, knowledge about the individual, and eliminating rules and processes that counteract participation and self-determination [

11]. Berlin Hallrup [

9] describes unilateral decisions from staff in group homes such as locking refrigerators and directing time for seclusion and for using a common area. The Health and Social Care Inspectorate in 2023 found that in 80 out of 90 inspected LSS-housings, two-thirds were using non-allowed coercive and restrictive measures [

13], negatively affecting the quality of life of people with intellectual disability [

22]. Many persons with intellectual disability have a limited guardian for support, but also in that relation, the person with intellectual disability often experiences being overruled or not being listened to [

12]. The Health and Social Care Inspectorate states that in reality, many persons living in LSS-housings do not have the right to live like others [

13]. This is in contrast to the assurance to support enabling persons with intellectual disability to “live like others”, under the Act on Support and Services for Persons with Disabilities (“LSS”) [

7]. Persons with intellectual disability are thus required to handle a situation where their strive to be actors in their own lives coincides with a strive to receive help in a system which shows a problem with acknowledging individual preferences in the interaction between the support person and persons with intellectual disability [

23]. Literature is however sparse regarding how persons with intellectual disability view their possibility to be an actor in their own life in situations where they interact with others. Some Swedish studies have reported on persons with intellectual disability striving to be actors in their own life, for example, in relation to self-advocacy [

24], daily-activity services [

20], claiming legal rights in work life [

25], or voting [

26]. Although support persons are present in the context of these studies, the relation between the support person and persons with intellectual disability is not in focus. Björnsdóttir et al. (2015) focus on the views of persons with intellectual disability in Iceland in regards to making their own decisions [

27]. In their study, persons with intellectual disability found it difficult to obtain appropriate information and assistance. In addition, in seeking ways to become autonomous, the participants considered other people’s perception of them. This finding suggests that persons with intellectual disability strive to take responsibility as actors in their own life, as well as for the interaction with support persons. However, to better support the development of autonomy in persons with intellectual disability, more knowledge about how persons with intellectual disability view their role in relation to support persons is needed [

27].

It is well known that, in general, giving support to persons with intellectual disability is a complex and demanding issue, with support persons using various strategies to guide the person with intellectual disability [

28,

29]. However, this issue also needs to be described from the point of view of the persons with intellectual disability, both because they are part of a dyad with the support person and because persons with intellectual disability may receive support from persons other than their officially appointed support persons, including strangers.

Acknowledging and expressing one’s own volition is important and a human right [

5,

30]. In persons with intellectual disability, the ability to make one’s own decisions may be diminished not only by the disability as such, but also by difficulties expressing one’s wishes. For this reason, it is important to study how persons with intellectual disability experience the situation of requesting support and how they reason about this in relation to their own volition. Given that autonomy is based on volition, as argued above, any shortcomings identified in the achievement of good support need to be viewed from the perspective of how persons with intellectual disability strive for autonomy within their actual situation. The aim of this study was to explore how persons with intellectual disability experience and reflect upon support in everyday life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This study used a qualitative design with an inductive approach in order to generate knowledge about how persons with intellectual disability perceive support in everyday life and in order to gain a deeper understanding of how the support they receive affects their autonomy in everyday life. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed using content analysis [

31,

32,

33]. In this article, the term “support person” will be used broadly to include not only professionals, but also family members, friends, and others.

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

Participants were recruited through the municipal social services in two different geographical areas of Sweden, one large city and one small town. The inclusion criteria to participate in interviews were people above 20 years of age with mild intellectual disability, having an occupation at a daily-activity center and lived either in a group home or a flat and received some support under LSS. Staff at daily-activity centers were enlisted to spread information about the study The staff was informed that participants should be included based on their own interest and not to be persuaded to participation. Additionally, in the invitation letter, it was informed that participants were allowed to choose someone to be present during the interview for support.

Thirteen individuals with mild intellectual disability (all more than 20 years old, six women and seven men) decided to participate. All of them had good communicative abilities. The participants worked at daily-activity centers, eight of them with an artistic focus and five in integrated units at companies. Eleven lived in group homes or apartments with support under the LSS, while two lived in their parental homes. Those living in group homes had access to on-site staff around the clock, while those living in apartments received support several times a week, depending on their needs. All participants except one were interviewed digitally at the work-site and received technical support from the staff. One person was interviewed digitally from home. One participant chose to be accompanied by a personnel during the interview.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

All information given to the participants was designed with cognitive accessibility in mind, with easy-to-read text, graphical support, and a PowerPoint presentation with illustrative slides and recorded spoken information. Each person signed an informed consent form before participating in the first interview. To make it even clearer to the participants regarding what participation in the study would involve, each of them was informed before the first interview started about the study and about the purpose of the interview. Then, the person was asked if he or she wished to participate and informed that it was possible to withdraw one’s participation without explaining why. Participants received contact information from the researchers and were encouraged to get in touch if they had any questions or thoughts. They were also encouraged to discuss any thoughts/concerns about their participation in the study with staff. At the end of the first interview, the participants were asked whether they wanted to take part in a second interview. All participants agreed to this; however, one participant later asked the staff to cancel the second interview. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref. No. 2020-03630).

2.4. Research Team

The research team comprised three experienced researchers, all with experience in qualitative research. They have backgrounds in occupational therapy and extensive clinical experience in rehabilitating children, adolescents, and adults with lifelong disabilities, such as intellectual disabilities, both professionally and as relatives. One of the researchers, MB, is a licensed trainer in the Talking Mats method and has extensive experience using Talking Mats in clinical settings and research. The first (A.-M.Ö.) and last (A.S.) authors had foundation training and are certified in Talking Mats methodology. All of the authors are female.

2.5. Data Collection

Individual interviews were conducted digitally in online video meetings (owing to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic) by the last author (A.S.). Each person was given the opportunity to participate in two interviews a few weeks apart. This was intended to give them time to reflect at home in peace and quiet on the topics that had come up during the first interview, in order to deepen their narratives. All participants except one took part in two interviews. (In fact, one participant even wanted a third interview, which was carried out and the data were included in the analysis). The interviews lasted for 30–60 min. They were audio-visually recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

At the beginning of the first interview, the interviewer shared an experience by showing a photo of a situation where she was receiving help from her daughter with her computer. By introducing this example, the interviewer indicated that the focus of the interview was on daily practical situations where one needs help. A semi-structured interview guide was used [

34] and the overall interview topic was whether the participant usually received help or helped others. For example, one question asked of the participants was, “Can you tell me about a time when you needed to ask for help?” Then, follow-up questions were asked, based on the person’s answer, for example, “How did you feel when asking for help?”. To gather knowledge about autonomy, the questions mainly referred to “independence” (självständighet), which was assumed to be a concept that the participants were familiar with and might relate to. As it turned out, the participants used that word mainly in relation to the performance of specific concrete tasks; the idea of becoming fully independent was not brought up.

The second interview was conducted using Talking Mats to further explore the areas raised in the first interview. Talking Mats is a structured visual communication framework designed to help people with communication difficulties express their feelings and opinions [

35]. Concretely, symbols representing the topic of a conversation, answer options, and a scale from positive to negative are placed on a mat. This helps participants to organize their thoughts and to express preferences or opinions effectively. One characteristic of Talking Mats is its reliance on open-ended questions—such as “What …” or “How …”—to elicit detailed responses rather than simple yes/no answers, which are less suitable for qualitative interviews. The interviewer plays a critical role in ensuring reliability. Successful use requires formal training in the method as well as the ability to be observant, adaptable, and skilled at interacting with individuals with intellectual disability [

36]. The Talking Mats framework can be used with a physical mat, but nowadays it is most commonly implemented digitally on devices such as tablets, laptops, or computers using a special application [

37]. It has proven to be an effective communication resource for persons with intellectual disability, supporting them in expressing their views by improving both the quantity and the quality of the information they share [

38,

39].

The focus of the second interview with each participant was based on what had emerged in the first interview. Symbols were chosen in advance from the Arasaac symbol database [

40] to represent topics, options, and scale steps in order to enhance discussions during the interviews. At the time of these interviews, the digital version of Talking Mats was not yet available. The interviewer used a makeshift solution during the online video interviews: the symbols were placed on an empty page in the PowerPoint presentation, which was shown on a shared screen. The interviewer placed the symbols in accordance with the participants’ answers, following the recommended Talking Mats procedure.

2.6. Data Analysis

The transcribed interviews were analyzed using qualitative content analysis [

31,

32,

33] to identify patterns, first in manifest content and then in the underlying abstract latent message. First, two of the authors (A.S. and A.-M.Ö.) read all the transcribed interviews to obtain an overall idea of the data material as a whole. The next step was to identify meaning units related to experiences of support in daily-life situations of persons with intellectual disability. The same two authors went through all meaning units together to revise and condense them. The condensed meaning units were brought together, discussed and coded, whereupon the authors compared the coded units by discussing them back and forth, thus gaining a deeper understanding of the totality of the data and becoming better able to reach the latent content and define categories. The initial categorization of the data yielded 33 sub-categories distributed across 6 categories. After an iterative analytical process of interpreting and abstracting, to identify the underlying meaning, the analysis finally yielded one overarching theme, three themes and eight sub-themes. The last author compiled the result.

3. Results

Thirteen people with intellectual disabilities participated in interviews about their experiences of support in daily life, six were women and seven men, all older than 20 years. Eleven persons participated in two interviews each, one person participated in three interviews and one person in one interview, giving a total of 26 interviews.

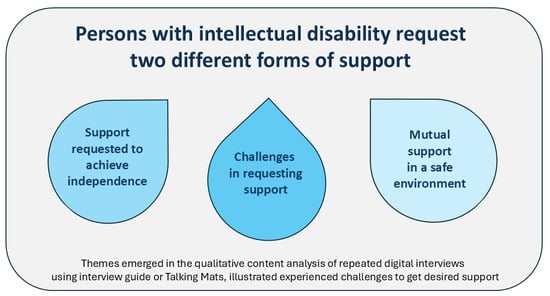

The analysis shows that it is a challenge for persons with intellectual disability to obtain the support they need in a way they want. This is apparent from all three specific themes identified—“Support requested to achieve independence”, “Challenges in requesting support”, and “Mutual support in a safe environment”. The three themes relate to each other and show two kinds of support requested by persons with intellectual disability. One kind of support is support where one can and wants to become as independent as possible. Another kind of support is where it is preferred to be situated in a supportive context where support is mutual and trustful, where one feels safe. That context can be both family, friends, workplace and housing, varying over time and sometimes complementing each other. The three themes can therefore be described in one overarching theme: “Persons with intellectual disability request two different forms of support”. The three themes, with their various sub-themes, that will be discussed below describe the multi-faceted factors that influence participants’ thoughts and actions regarding support. Illustrative quotes from participants are given; they have been translated from Swedish by the authors.

3.1. Support Requested to Achieve Independence

3.1.1. Independence Is Important and Achievable

Independence was generally very much related to a positive feeling: feeling free to do what one wants means a lot to the participants. Being independent was characterized as important, nice, and easy. It makes one feel satisfied and happy. Independence can refer both to doing things on one’s own and to having the right to decide things on one’s own:

Well, one part of independence is that you can cook for yourself and can tell the time and so on, but another part of it is about having rights. If you live by yourself in a home, you must still have the right to determine your own life.

(A3:2)

Doing things on one’s own was found desirable by all participants. The activities concerned ranged from cooking and voting to travelling alone and reading poems to an audience. It feels better to learn things and to be able to do them oneself than to remain dependent on receiving help:

When it comes to independence, it kind of feels more fun to understand how to tell the time if you think that you can do it yourself.

(A3:1)

At a more existential level, independence was also related to being a genuine person, who takes pride in thinking for oneself, does not have to pretend, and actually knows and understands things:

Yes, it feels good [to know something yourself], easier somehow. That you’re not pretending. You really know. And that you don’t have to ask some unknown person. You can explain it to yourself.

(A3:2)

One participant even compared not being independent to being a slave or a robot:

You should have independence. It’s an important right in life, otherwise you might as well be called a slave or robot or something like that. Because independence, that’s something you have so that you can be independent and have your own opinions.

(B4:1)

Hence, being independent is of great importance to the participants, both in practical deeds and in governing one’s life. The way independence was described, it appeared as something achievable. Independence was viewed as the ability to become as independent as possible, despite the limitations imposed by disability.

3.1.2. Directing the Help Is Necessary

In situations where help needs to be requested, one can be active both in requesting help and in defining what kind of help one wants. This may lead to an experience of receiving support on one’s own terms, which makes it possible to keep one’s sense of independence:

That you decide for yourself when you want help and when you don’t want help. That you decide this for yourself, so that nobody else decides it for you.

(A1:1)

Support that one can control oneself makes one feel good, grateful, and happy. This can occur, for example, when calling staff to ask to be met at the bus stop. Sometimes, one has to take command of a situation in which one is not satisfied with the support. One participant described how a taxi driver insisted on accompanying him into his place of work, although he explained that the arrangement was that he was able to manage on his own. The participant then called the transport company directly and received support from them in that they told the driver about his mistake:

- Participant (P):

- […] He didn’t want to drop me off, he wanted to come up with me. I want to go up by myself. Then I asked at [company], “Am I supposed to go up by myself?” “That’s the point, you’re not supposed to have anyone with you.”

- Interviewer (I):

- Did you call [company] yourself?

- P:

- I called them myself

- I:

- And it went well?

- P:

- It went well. He was reprimanded. So they understood that he had made a mistake. (A4:1)

Directing the help was easier if the person was involved when the task was carried out, doing things together was preferred. For example, staff or parents could pay the bills on the computer, but the person with intellectual disability should be present and they should discuss together what was being done. Another way of being involved and experiencing independence in the support situation was when the person with intellectual disability and the support person focused on different parts of a broader task, for example, that one person dusts and the other wipes the floors when cleaning. Deciding together how to share the work yielded a sense of being in control.

Directing the help and taking part in the activities instead of handing things over to the support person were thus important aspects for achieving independence. Being able to request support in a way that one thinks feels good both for the support person and for oneself makes one feel satisfied both with the support and with having control of the situation.

The theme shows that independence is important and can be achieved by directing the support needed and thus having control of the situation.

3.2. Challenges in Requesting Support

3.2.1. Insecurity Hinders Asking for Help

Asking for help is not always easy and participants said that they sometimes dared not do so. Furthermore, sometimes they did not receive help despite asking, and sometimes they had to remind a support person that they needed help. Asking strangers for help can be difficult, and it can be hard even with people one knows well. For example, one may be afraid to interrupt or to disturb:

- I:

- The people helping you, how do they know that you need help?

- P:

- Sometimes I tell them, sometimes I’m afraid to tell them because I don’t want to take up too much space. I’m afraid of interrupting someone nearby, like a member of staff who’s helping someone else, and then I’m usually the one who sits quietly. And then I’m usually afraid to say that I need help. (A8:1)

Not being able to do something (such as telling the time) can be embarrassing and cause feelings of awkwardness, leading to both anger and sadness. Sometimes participants did not receive help to learn for themselves and did not know why. Several describe that they sometimes feel ashamed and feel stupid, shy, and helpless. As one of them said:

Helpless, yes, and then ashamed.

(A6:1)

The risk of not being able to understand the answer may undermine the wish to ask for help:

And if I ask someone the time and they answer “13:30”, then maybe I don’t know what 13:30 is, and then it gets a little weird, ha-ha.

(A3:1)

Asking for help is more difficult for people who perceive themselves as shy, but even those who do not may find it hard:

If I have someone I know with me, like a staff member, I usually ask them. If I don’t have anyone with me, then I ask anyway. Because I’m not shy in that sense. Of course it’s so hard to ask someone else, but in the end I usually ask anyway. I’m curious to know.

(B4:2)

Participants also mentioned that they might feel uncomfortable when staff members encouraged them to ask for support. Indeed, one participant noted that staff members could become angry with someone for sitting quietly instead of asking for help. In addition, it may also be the case that one actually does not know why it feels difficult to ask for help.

Feelings of shame for shortcomings and fear of not being able to understand answers thus became barriers to asking for help. Maintaining independence and integrity was more difficult in situations where one felt insecure, either due to not knowing the person or due to feeling criticized.

3.2.2. Easier to Ask for Help in Trustful Relationships

Participants stressed the importance of obtaining help from a person they trusted, whether family members, friends, or staff. They described how crucial it was to trust that the person they confided in would not share their information with others:

Yes, it depends. I find it a bit difficult to tell anyone things, but I have good staff. Still, some people I tell things and others I don’t tell anything, because it’s a bit about trust, too. I mostly see it as things like that.

(B1:2)

Many felt an extra sense of security with staff who are subject to confidentiality rules, as they could share things in confidence without risking them being passed on to others.

It was deemed essential that the family member or staff member whom participants asked for help should respect their wishes and opinions about what they wanted:

That they respect my wishes, so to speak. So that I get the feeling that I have the right to decide in my own flat.

(A3:1)

It was easier with experienced staff, because then the participants did not have to explain each time what support they needed and how they wanted to be supported, which made it easier to ask for help:

But that’s because if you’ve seen someone many times and you know how that person works, then you get to know them. Then it’s even easier to ask for help.

(B4:2)

In general, new staff were challenging, especially temporary staff in the summer. It was difficult when they were unfamiliar with things, forcing participants to repeatedly explain what help they needed. However, the need to adapt to the support person could be reduced if information about the participant’s preferences for help was available at the staff office:

[…] but sometimes I do get good help from temporary staff, because they read in a binder at the staff [office]. Because they have a binder that belongs to me, so they read [that] today she needs this help and then I get that help from that temporary staff member too.

(B3:2)

Some participants expressed that it was difficult when a staff member who they felt they had worked well with left his or her job. Furthermore, receiving help from a person one does not like can feel awkward. More generally, participants found it easier to deal with accommodating and cheerful people than with people who are more withdrawn or unpleasant, even when the former provided too much support.

Trustful relationships were thus important for requesting support in a good way that promoted independence. Trustful relationships were assured by long time relations and positive personal characteristics in the support person, such as assuring confidence and being positive.

3.2.3. Continuous Development in Asking for Help

Participants report that they may feel squeezed in between the discomfort of not being able to do something and the discomfort of asking for help. This may cause them to challenge their concerns, causing them either to ask for help or learn to manage on their own:

At the same time, I try to tell myself, quietly to myself. That “hey, wouldn’t it be nice to do this on your own?” Because it would be nice not to be dependent on others. In some situations I win out over the fear, and sometimes the fear wins out over me.

(A3:1)

Furthermore, participants note that they may want to become autonomous in many respects but need to take things one at a time. Hence, they may plan to learn more things later on, for example, how to wash or vote. Learning to do things independently is a gradual process where one learns from staff members, one’s mother, TV, films or other sources. Becoming autonomous is easier if one is encouraged to strive in that direction from early on in childhood. Acting on stage may be a good way to reduce shyness and worries about asking for help. Doing a thing together with a support person is good, because then participants will be able to think back to this experience when doing the same thing on their own:

You have to learn to ask for help, you can’t be shy, you have to dare.

(A7:3)

[…] if you want help, you must have the courage to ask and be more assertive than you normally are.

(A2:2)

Paying attention to the support person at the same time was important. One participant exemplified this by saying:

[…] you have to sound a bit more assertive but at the same time not too mean. Because then the other person [the staff member] might step back.

(B1:2)

Support persons may also both make it easier to ask for help and reduce the need for support by providing encouragement and offering specific training projects. For example, the participant quoted below received support in taking the lift up to work on his own, instead of being met by staff:

So when I started this job, I wanted people to come and meet me. And then they asked if I’d thought about trying to ride by myself. And I of course started hesitating: “well, I don’t know …” Then what we did was that the leader put a blanket over himself and helped me get rid of my fear. And when I came out of the lift after I had ridden by myself, I just felt that “oh, I did it. I did it!”

(A3:1)

However, there may be a conflict between the support given by people who encourage independence and that given by people who want to help. In the case of the lift training described above, staff encouraged the person to go alone in the lift, but the receptionists at the entrance wanted to be helpful which caused conflicting feelings in the participant concerned.

One participant experienced a change when he first had staff who were dominant and then had new staff who encouraged his own will, which led him to make more of his own decisions:

- I:

- It sounds like you’re very sure of what you want to say and what your rights are and so on, how did you get there?

- P:

- Before, I found it harder to express what I wanted to do. And I think that since the old bosses left and the others took over, then they said, why should you ask us what you want to do? If you want to do this or that, we won’t interfere. […] What I feel is that I find it easier nowadays than in the past to come forward with what I want to do.

- I:

- Yes, and what’s made that easier for you?

- P:

- Well, now I feel there’s nobody who can deny me, there’s nobody who can tell me off or stop me. They can never stop me, but they can make recommendations and suggestions. And that’s better. (A 3:2)

Participants could also experience that staff encouraged the person to be independent towards their parents but did not allow independence from the staff:

A staff member then said that ‘I know you want to go to your mum, but I think you should stay here so that you can learn to do things yourself’. And then I felt that right now I feel there’s no difference if I live here or at home. I feel that I’m being treated as if I had extra parents.

(A4:1)

Participants thus strived to take more responsibility and achieve independence over time. The encouragement of independence from support persons was valuable, but inconsistencies in messages regarding independence from different support persons could lead to conflicts.

The theme shows that insecurity and low self-esteem, together with feelings of fear and shame may hinder the process of requesting help. This could be counteracted by trustful relationships based on long time engagement with trustable persons. Participants strived for developing an optimal way to request help.

3.3. Mutual Support in a Safe Environment

3.3.1. Receiving Help Can Be Comforting

Despite the desire to be in control of what help one receives, it also feels good that those around one know what one needs help with, that one does not have to tell them. For instance, a family or staff member may know from experience, or a staff member may learn from one’s implementation plan or weekly schedule what help one wants and thus not have to ask every time. Furthermore, knowing that one will have access to help in an emergency situation, such as an epileptic seizure, can add to a sense of security. It can also be nice not always having to do everything that one is able to do. For example, a participant may be able to make a sandwich himself but still appreciate it when his mother comes to visit and makes him a sandwich, even though the staff may then say that he missed a chance to be independent:

- I:

- But in situations like now, when you were going away, do you get help from the staff with breakfast or getting away or anything?

- P:

- Well, I make sandwiches myself. Sometimes I sleep very late at the weekend and then I usually ask if they [the staff] can make me a sandwich. But then they answer that I can do it myself, that I kind of would lose an opportunity to be more independent, they say. (A3:2)

One participant pointed out that for someone who only needs support with certain things, such as cooking and doctor’s appointments, but can manage other everyday activities, it could be hard to be alone in one’s flat. If such a person was very sociable and wanted company every day, this could be difficult to obtain through the social-welfare services, since they assess the support someone needs to perform everyday activities:

[…] I’m a social person, so I want company all the time […] I’m a social person who wants company from the staff, and when they don’t have time, I have to be on my own, doing a few different things by myself.

(B2:1)

No one else described this kind of support functioning as a social security, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, the participants received less help than before and became more lonely, lacking interaction with others such as staff, family, and friends. They described how, because of pandemic-related restrictions, they were no longer allowed to do things they had previously done themselves, such as shopping or washing clothes in the common laundry room:

Not being independent. What I can do myself, I can’t do any more.

(A1:1)

The support provided during the pandemic was characterized as impersonal owing to the protective equipment worn by staff. Not receiving the help they needed was difficult but also increased loneliness:

- P:

- Yes, but they came with medicine, with visors and protective clothing and everything. It’s hard. Hard to be alone that much.

- I:

- Did you ask for help and they couldn’t help you, or what?

- P:

- Yes, a bit like that, actually. I want company as well, you know. But they [the staff] didn’t dare. (A1:1)

In parallel with the strive for independence and doing things on one’s own, receiving support was also regarded as part of social interaction. Receiving support, without having to request it, could be comforting and prevent loneliness.

3.3.2. Helping Each Other

Helping each other was important, whether it involved staff, family, or friends. Work at daily-activity centers was described as a context where people helped each other and felt needed.

Participants emphasized that solving things together with friends was easier, noting that if they received help from someone who was not used to a situation, they could work it out together. In one participant’s words:

Then you can check it together, how to go about it, you get your heads together and you are together.

(A7:2)

Spending time with friends, socializing and helping each other with things that need to be done in everyday life, was described by many participants as essential:

They [my friends] usually ask for help and they help me and I help them and we usually spend time together and do things and hang out then.

(B2:2)

Participants noted that helping their friends made them feel needed and increased their self-esteem and self-efficacy. One of them said:

[…] going to work, I feel needed every day, and I’m very, very conscientious about my duties. If I didn’t feel needed at work, then I would probably feel that, well, here I am doing this job, but nobody appreciates my performance and what I’m doing, so I might just as well sit here and do nothing then.

(B4:1)

Sometimes participants chose not to ask for help at all if they felt that a staff member was stressed or if he or she was new on the job. The participants understood that their staff were sometimes very busy and that, for this reason, it was a good idea to ask them for help at the right time. Given the support person’s situation, participants might try to manage without assistance. Additionally, when requesting support, it is important to pay attention to the support person’s response:

You should do what feels best […] and then of course you notice what response you get from the other person.

(A2.2)

Support was not always uni-directional, rather, helping each other was important, whether it involved staff, family or friends. Work at daily-activity centers was described as a context where people usually helped each other and felt needed.

3.3.3. Family Members and Friends Form a Natural Context and a Back-Up

Asking family members was often deemed easier by the participants. For example, the help requested could involve being driven somewhere or concern a new situation where participants needed to see how things worked, such as voting for the first time. In addition, participants might ask family members when the staff were busy. In some cases, participants both received help with an activity and had an opportunity to talk about a difficult matter with someone close to them, at the same time:

[…] It′s getting help with how to do laundry and chatting a little about feeling left out and things like that […] It feels good to have someone you can talk to, someone who understands.

(A 7:1)

Asking a family member what to do could be a solution in situations where participants felt that they were not receiving the support they needed or were not understood by staff at their assisted-housing facility:

And sometimes I’ve actually gone so far as to call my mum and told her that they don’t understand me here, I’m not getting the help I should be getting.

(A 8:1)

However, when family members lived far away, asking them for help was not seen as an option.

Finally, asking a close friend for help usually worked well, but in some situations it was inconvenient, for example, with regard to more private matters such as personal hygiene, including showering:

It depends on which friend it is. The difference is that the staff know what to do and so on, and they have some experience. Then it’s more or less a routine matter: this is how to do this. If it’s a friend or a mate, you have to think about what the situation is. Of course, I could ask a friend for help, maybe with food or maybe with whether I should take a shower or something. But I don’t know, I don’t know if I’d ask my friend to help me wash.

(B5:1)

Family and friends were thus an important part of the support also if the person lived in LSS-housing. Asking family for help sometimes felt more natural and although family members encouraged independence, support and comfort were more natural parts of the interaction, yielding a less demanding situation.

In summary, the results show that the situation of requesting and receiving support is complex and that persons with intellectual disability need to develop strategies and skills enabling them to request support in a way that they find socially and personally acceptable in order to become independent on their own terms. Independency is of high importance and can be achieved also by directing the support needed. However, independency also needs to be balanced with undemanding contexts where support is yielded without being requested. Participants’ view of requesting and receiving support was in line with being an actor in one’s own life.

4. Discussion

This study has presented new knowledge about how persons with intellectual disability view the situation of requesting and receiving support in daily life. The analysis of interview data yielded three themes “Support requested to achieve independence”, “Challenges in requesting support”, and “Mutual support in a safe environment”. This complexity is embedded in social situations, where persons with intellectual disability assume responsibility both for themselves and for the support persons.

The overarching theme yielded by the analysis showed that persons with intellectual disability request two different forms of support. The first form was related to independence and the second to being part of a supportive context. For implementation, this means that support persons need to think in two tracks simultaneously regarding support; one track that strives to support the person in developing a way to manage on one’s own and another track that strives to support the person with a trustful, supportive context. This finding may explain a difficulty presented in literature, showing that if support persons are promoting independence, it is in reality hindered by a sense of responsibility for protecting the person with intellectual disability from harm [

41,

42,

43,

44] or by structural hinders such as the staff’s work load [

41]. Understanding the dualistic forms of support needed, expressed by persons with intellectual disability themselves, may facilitate the tailoring of support and communication about various needs in the complex situation of giving/receiving support.

The high importance of experiencing independence in one’s life, described in the first theme, was a significant finding in this study. Independence was however not considered in the view of becoming fully independent. This is in line with the idea that autonomy and independence can never be fully achieved [

16]. Being in need of support did not counteract independence as long as the person could direct the support. Opportunities for directing the support could emerge in situations where one asked for specific help, but also when taking active part in any situation and in solving the problem together with the support person. The importance of directing/controlling the help has also been described in a previous study [

45].

The strive for achieving independence also in support situations described here has not been acknowledged from the perspective of persons with intellectual disability earlier and is important knowledge when tailoring support. Given that independence and directing the support are of high importance, being able to tell what support one needs is crucial. Several participants expressed hinders for achieving the support they wanted; both hinders related to the social environment and to oneself. Whereas hinders in the social environment have been given attention earlier [

41,

42], the internal hinders experienced by the person (such as shyness or insecurity) have not been acknowledged in literature to the same degree. Several reports point out that the level of competency in staff and directors in LSS-housings needs to be increased [

10,

11,

13]. The current study however implies that developing interventions to strengthen the person in asking for and directing support is an important complement to educating staff and directors.

Another finding of the present study was that the persons with intellectual disability provided concrete descriptions of how they thought about their own development towards independence in directing support and acted to promote that development. In some cases, people around them encouraged or even urged such a development. The reasoning of the persons with intellectual disability often reflected a strategy involving small steps, often pertaining to concrete tasks, such as tidying alone or visiting the health-care services on one’s own. To our knowledge, internal reasoning on how to develop towards independence is another aspect that has not previously been described in persons with intellectual disability.

Participants also described strategies for dealing with excessive support, which may prevent a person from developing in his or her performance of everyday activities. To some of them, it felt best not to question the support person, meaning that they accepted the support offered. However, others had developed ways of saying no in a kind and smooth way. It has been described in earlier research regarding persons with intellectual disability, where it has been found that misdirected support may cause persons with intellectual disability to stop taking the initiative in acting themselves [

46]. In the present study, participants described clearly that their right to support develops their ability to do things in their own lives, gives them self-esteem, and allows them to find their own strategies in different situations. Being able to make decisions in well-known situations and being autonomous in terms of actions were deemed important. This finding is consistent with previous studies [

47,

48]. Ribenfors et al. (2025) referred to autonomy in daily life as “day-to-day autonomy”, which involved being in control and having one’s decisions respected in daily life, with support from staff [

49]. It can be concluded that the design of support in new situations is crucial for whether persons with intellectual disability will be able to develop further independence and autonomy and whether they will be able to manage their own lives to a greater extent [

49].

The findings further show that support goes beyond practical compensation for disability—it is interwoven with a need for belonging and social interaction. This was also reported by Gappmayer (2023), stating that residents observed in the study would lose their main social interactions if they managed activities on their own [

41]. It should be kept in mind that when decisions are made about the staffing of assisted-housing facilities or daily-activity centers, to ensure that the staff will have time not only to provide services but also to socialize. Alongside staff, family members were described in the present study as important both for practical support and for social belonging. It has been reported in previous research [

50] that persons with intellectual disability often rely on relatives to help them apply for the support they are legally entitled to and generally to find their way in the formal system of official support. However, the social aspect of belonging to a family and receiving support from family members is sparsely described in the literature. In addition, many persons with intellectual disability in Sweden became more isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic [

51], which was also described in the present study.

The present study shows that having support persons whom one trusts and who know what one needs is a prerequisite for being able to decide when and how one wants various kinds of support. Development towards independence requires an interaction between the person with intellectual disability and his or her social environment, in which that person’s right to make decisions about his or her own life is acknowledged in line with the UNCRPD [

5]. The analysis clearly showed that trust and confidence in the person giving support is of great importance, whether that person is a professional or a family member or friend. However, one unexpected finding related to the amount of consideration given to support persons. For example, participants reported not asking for support when they believed that this would impose a burden on a support person or when they did not trust a support person. This may be due to a vulnerability that they felt because they were dependent on other people in their everyday lives. As a result of this consideration, they would constantly weigh options in terms of when and how to ask and whom to turn to for support.

For example, they might refrain from asking for support if a support person was stressed or tended to be demanding. To our knowledge, this internal process of considering and weighing up various options has not previously been described in the literature about persons with intellectual disability.

The present study has contributed to the ongoing development of knowledge by describing how persons with intellectual disability view support situations. Given that persons with intellectual disability strive to obtain support in a way that enables them to maintain their autonomy, there is an obvious need for guidance for support persons. Research shows that such guidance should highlight the need to consider the abilities of the person with intellectual disability when making decisions [

52,

53]. Given that Swedish reports show that respecting the autonomy of persons with intellectual disability is a complex issue, it is of importance to develop specific knowledge about the role of support persons in the Swedish context.

Strengths and Limitations

This study explores how persons with intellectual disability experience support in their everyday lives. To the knowledge of the authors, this is the first study describing the views and experiences of persons with intellectual disability from the perspective of volition and autonomy in relation to requesting support. This study, involving participants from two geographical areas in Sweden, reflects those participants’ own perceptions of support rather than applying the perspective of the persons giving support. The new knowledge provided by the study is particularly important given that persons with intellectual disability are under-represented in research studies [

54].

When interviewing persons with intellectual disability, it is important to take steps to ensure understanding, facilitate reasoning, enhance reflection, and promote detailed responses. The first interview was semi-structured and provided the opportunity to elicit a wide range of experiences and reflections on the support people receive in their daily lives. The decision to include the Talking Mats methodology in the second round of interviews was made to deepen the narratives around what was covered in the first interview. The Talking Mats may be useful for this purpose [

35,

36]. Its use in qualitative research does entail certain restrictions. For instance, the interviews have to be fairly structured, and the questions need to be pre-defined to a large extent. However, these drawbacks can be considered acceptable given the aim of enabling participation by a group that is under-represented in research.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were performed digitally. At the time of data collection, there was no Talking Mats application available that was suitable for online interviews (such an application was under development and is now available). However, a similar setting was created using standard software. While this solution worked well for its purpose, a dedicated application would of course have been preferable.