Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

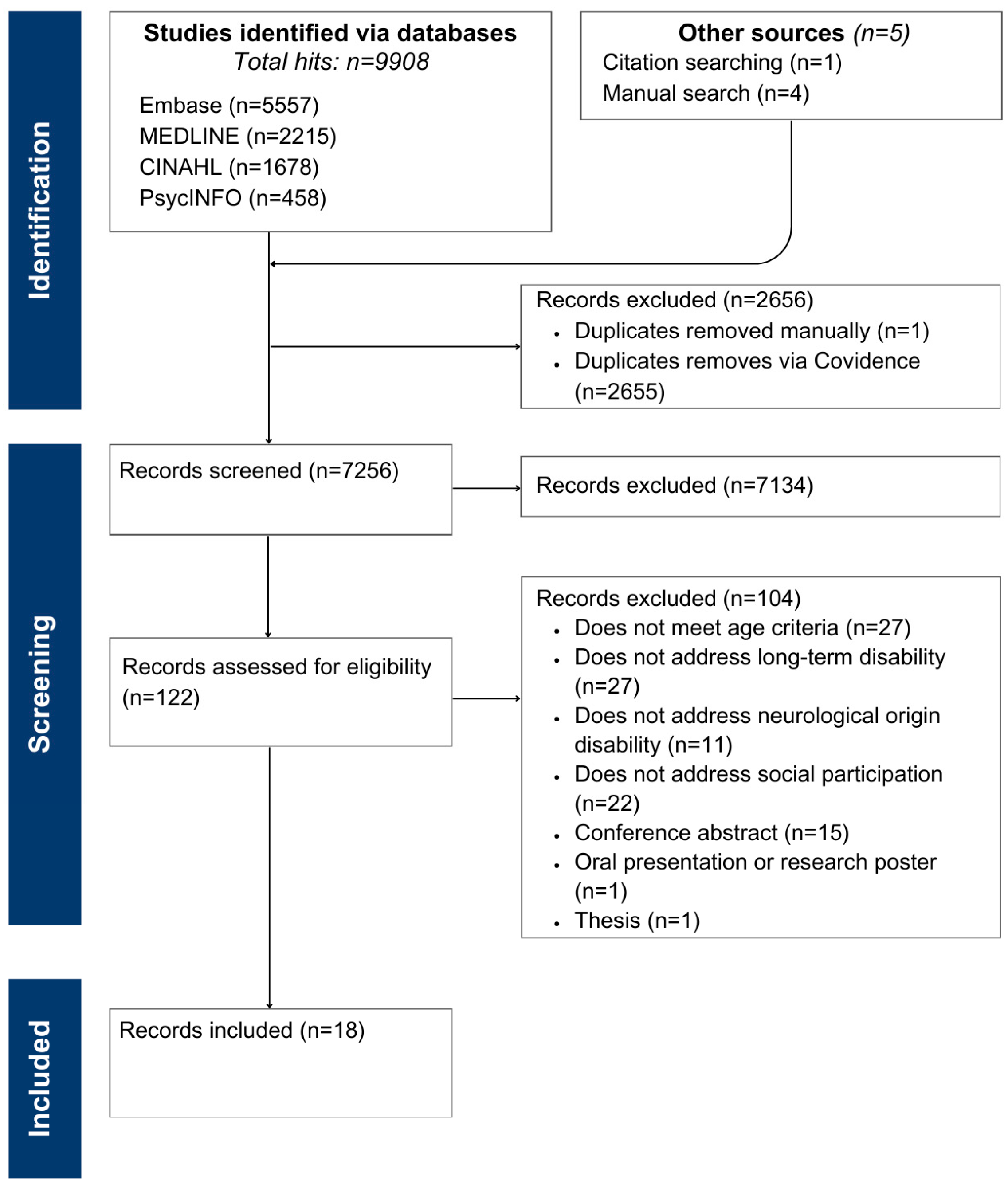

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

- What is the state of knowledge concerning social participation among adults aging with a long-term neurological disability?

- What are the barriers and facilitators to social participation in the target population?

2.2. Concepts

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Context

2.3.3. Document Types

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Source of Evidence

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Selected Articles

3.2. Facilitators and Barriers to Social Participation

3.2.1. Personal Factors

Identity Factors

Organic System

Capability

3.2.2. Environmental Factors

Micro-Environments

Meso-Environments

Macro Environments

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Future Studies

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| # | Query | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (((“Nervous system” or Neuro* or Brain) adj2 (Dis* or Impair* or Function* or Dysfunction* or Injur*)) or “Neuro* incapa*” or “Neuro* limit*” or “Head injur*” or “Multiple sclerosis” or Parkinson* or TBI* or Trauma* or Hemiplegi* or Paraplegi* or Tetraplegi* or Quadriplegi* or Myelopath* or Handicap* or Stroke* or “Cerebrovascular accident*” or Pares* or Hemipares* or Paralys* or “Spinal cord injur*”).ti,ab. | 1,602,325 |

| 2 | Nervous system diseases/or exp Brain injuries/or Parkinson Disease/or exp Stroke/or exp Traumatic brain injuries/or exp Multiple sclerosis/or Spinal cord injuries/or Paraplegia/or Quadriplegia/or exp Craniocerebral trauma/or Paresis/or Paralysis/ | 629,381 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 1,781,769 |

| 4 | ((aged or old*) adj2 (person* or individuals* or adult* or citizen* or population or individual*)) or elder* or ageing or aging.ti,ab. | 770,331 |

| 5 | aging/or aged/ | 3,578,096 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 3,871,089 |

| 7 | ((social or community or societ*) adj2 (participation or engag* or involv* or inte* or implicat* or reintegrat*)).ti,ab. | 134,200 |

| 8 | social integration/or community involvement/ | 18,725 |

| 9 | 7 or 8 | 149,452 |

| 10 | 3 and 6 and 9 | 2111 |

| Doi | Author | Article Title | Year of Publication | Study Location | Study Purpose | Study Design | Study Sample | Data Collection Method | Precise Methodology | Conceptualization/Definition of Social Participation | Facilitators and a Barriers to Social Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- Sabri, S.M.; Annuar, N.; Rahman, N.L.A.; Musairah, S.K.; Mutalib, H.A.; Subagja, I.K. Major Trends in Ageing Population Research: A Bibliometric Analysis from 2001 to 2021. Proceedings 2022, 82, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghneim, M.H.; Stein, D.M. Age-Related Disparities in Older Adults in Trauma. Surgery 2024, 176, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.T.A.; Addo, K.M.; Findlay, H. Public Health Challenges and Responses to Growing Ageing Populations. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Janssens, A.; Tomlinson, R.; Williams, J.; Logan, S. Towards a Definition of Neurodisability: A Delphi Survey. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-H.; Yeh, T.-T.; Yen, H.-Y.; Hsu, W.-L.; Chiu, V.J.-Y.; Lee, S.-C. Impacts of Stroke and Cognitive Impairment on Activities of Daily Living in the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, P.; Hentsch, L.; Seeck, M.; Zekry, D.; Graf, C.; Fleury, V.; Assal, F. Neurology of Aging: Adapting Neurology Provision for an Aging Population. Neurodegener. Dis. 2024, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, T.; Karatekin, B.D. Determinants of Social Participation in Individuals living with Disability. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, C.; Amano, T.; Reynolds, A.; Jia, Y. Influences of Having Cognitive Impairment or Dementia on Social Engagement among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Lussier-Therrien, M.; Biron, M.L.; Raymond, É.; Castonguay, J.; Naud, D.; Fortier, M.; Sévigny, A.; Houde, S.; Tremblay, L. Scoping Study of Definitions of Social Participation: Update and Co-Construction of an Interdisciplinary Consensual Definition. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, A.S.B.; Petersen, S.; Dragsted, A.C.; Kristiansen, M. Social Interventions Targeting Social Relations among Older Individuals at Nursing Homes: A Qualitative Synthesized Systematic Review. Inq. J. Med. Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2019, 56, 46958018823929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Z.; Wu, C.; Gao, T. The Impact of Social Participation on Subjective Wellbeing in the Older Adult: The Mediating Role of Anxiety and the Moderating Role of Education. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1362268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.A.; Sommer, J.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Koven, L. A Profile of Social Participation in a Nationally Representative Sample of Canadian Older Adults: Findings from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can. J. Aging Rev. Can. Vieil. 2022, 41, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, M.-J. Un défi pour nos interventions de promotion de la santé: Mieux rejoindre les personnes ainées en situation de vulnérabilité 2023. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/2024-01/3440-interventions-promotion-sante-personnes-ainees-vulnerabilite.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Kuang, L.; Yang, X.; Yu, B.; Cui, Y. Risk Factors for Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2024, 41, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Peng, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Liao, X.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, X. Factors Associated with Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 322–330.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Chiu, H.F.-K. Ageism, Dementia, and Culture. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 35, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcotte, S.; Simard, P.; Levasseur, M.; Raymond, É.; Routhier, F.; Lamontagne, M.-È. Social Participation Experiences of Older Adults with an Early-Onset Physical Disability: A Systematic Review Protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, B.G.; Chen, J.T.-H.; Wuthrich, V.M. Barriers and Facilitators to Social Participation in Older Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin. Gerontol. 2021, 44, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilberink, S.R.; van der Slot, W.M.; Klem, M. Health and participation problems in older adults with long-term disability. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.J. Benefits and Barriers to Physical Activity for Individuals living with Disabilities: A Social-Relational Model of Disability Perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Seniors Council. Who’s at Risk and What Can Be Done About It? A Review of the Literature on the Social Isolation of Different Groups of Seniors; National Seniors Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-0-6488488-0-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fougeyrollas, P. Classification internationale ‘Modèle de développement humain—Processus de production du handicap’ (MDH—PPH, 2018). Kinésiethér. Rev. 2021, 21, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, É.; Grenier, A.; Lacroix, N. La participation dans les politiques du vieillissement au Québec: Discours de mise à l’écart pour les aînés ayant des incapacités? Dév. Hum. Handicap Change Soc. Hum. Dev. Disabil. Soc. Change 2016, 22, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Scharf, T.; Keating, N. Social Exclusion of Older Persons: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (Ed.) Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 978-92-4-154730-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergström, A.; Guidetti, S.; Tham, K.; Eriksson, G. Association between Satisfaction and Participation in Everyday Occupations after Stroke. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 24, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Lamers, I.; Bertoni, R.; Feys, P.; Jonsdottir, J. Participation Restriction in Individuals living with Multiple Sclerosis: Prevalence and Correlations with Cognitive, Walking, Balance, and Upper Limb Impairments. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Twardzik, E.; Meade, M.A.; Peterson, M.D.; Tate, D. Social Participation among Adults Aging with Long-Term Physical Disability: The Role of Socioenvironmental Factors. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 145S–168S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalemans, R.J.P.; de Witte, L.; Beurskens, A.J.H.M.; Van Den Heuvel, W.J.A.; Wade, D.T. An Investigation into the Social Participation of Stroke Survivors with Aphasia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalemans, R.J.P.; de Witte, L.; Wade, D.; van den Heuvel, W. Social Participation through the Eyes of Individuals living with Aphasia. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2010, 45, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alisa, S.; Baudo, S.; Mauro, A.; Miscio, G. How Does Stroke Restrict Participation in Long-Term Post-Stroke Survivors? Acta Neurol. Scand. 2005, 112, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingrich, N.; Bosancich, J.; Schmidt, J.; Sakakibara, B.M. Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Social Participation after Stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2023, 30, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, T.J.; Worrall, L.E.; Hickson, L.M.H. Interviews with Individuals living with Aphasia: Environmental Factors That Influence Their Community Participation. Aphasiology 2008, 22, 1092–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, M.; Gustafsson, L.; Meredith, P. Personal Factors, Participation, and Satisfaction Post-Stroke: A Qualitative Exploration. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 30, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dorze, G.; Salois-Bellerose, É.; Alepins, M.; Croteau, C.; Hallé, M.-C. A Description of the Personal and Environmental Determinants of Participation Several Years Post-Stroke According to the Views of Individuals Who Have Aphasia. Aphasiology 2014, 28, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundström, U.; Lilja, M.; Gray, D.; Isaksson, G. Experiences of Participation in Everyday Occupations among Persons Aging with a Tetraplegia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundström, U.; Wahman, K.; Seiger, Å.; Gray, D.B.; Isaksson, G.; Lilja, M. Participation in Activities and Secondary Health Complications among Persons Aging with Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matérne, M.; Simpson, G.; Jarl, G.; Appelros, P.; Arvidsson-Lindvall, M. Contribution of Participation and Resilience to Quality of Life among Persons Living with Stroke in Sweden: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2022, 17, 2119676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlander, A.; Iwarsson, S.; Jönsson, A.-C.; Lindgren, A.; Månsson Lexell, E. Living and Ageing with Stroke: An Exploration of Conditions Influencing Participation in Social and Leisure Activities over 15 Years. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, E.T.; Campbell, M.L.; Koon, L.M.; Rogers, W.A. Transportation Challenges for Persons Aging with Mobility Disability: Qualitative Insights and Policy Implications. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, G.; Frankel, H.L.; Jamous, M.A.; Soni, B.M.; Charlifue, S. Participation Restriction and Assistance Needs in Individuals living with Spinal Cord Injuries of More than 40 Year Duration. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2018, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparling, A.; Stutts, L.A.; Sanner, H.; Eijkholt, M.M. In-Person and Online Social Participation and Emotional Health in Individuals living with Multiple Sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 3089–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, S.; Simard, P.; Piquer, O.; Lamontagne, M.-E. “I’m Aging Faster”: Social Participation as Experienced by Individuals Aging with a Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Park, G.-R.; Namkung, E.H. The Link between Disability and Social Participation Revisited: Heterogeneity by Type of Social Participation and by Socioeconomic Status. Disabil. Health J. 2024, 17, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, T.C.; Hrozanova, M. Chapter 12—Chronic Pain and Fatigue. In Neuroscience of Pain, Stress, and Emotion; al’Absi, M., Flaten, M.A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 253–282. ISBN 978-0-12-800538-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Graff, L.A.; Patten, S.B.; Bolton, J.M.; Fisk, J.D.; Hitchon, C.; Marriott, J.J.; Marrie, R.A. Pain and Participation in Social Activities in Individuals living with Relapsing Remitting and Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J.-Exp. Transl. Clin. 2023, 9, 20552173231188469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Kratz, A.L.; Whibley, D.; Poole, J.L.; Khanna, D. Fatigue and Its Association with Social Participation, Functioning, and Quality of Life in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.; Kirkby, A.; Eccles, F.J.R. A Meta-Ethnographic Synthesis of the Experiences of Stigma amongst Individuals living with Functional Neurological Disorder. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 220.

- Carr, K.; Weir, P.L.; Azar, D.; Azar, N.R. Universal Design: A Step toward Successful Aging. J. Aging Res. 2013, 2013, 324624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, C.; Louceiro, J.; Dias, L.; Moreira, A.; Kotradyová, V.; Čerešňová, Z.; Kacej, M.; Filová, N.; Šimková, M.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Design for All: An Overview of Needs and Gaps in Formal Education in Four European Countries. Interdiscip. Perspect. Built Environ. 2023, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H.; Hitch, D.; Watchorn, V.; Ang, S. Working with Policy and Regulatory Factors to Implement Universal Design in the Built Environment: The Australian Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 8157–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielegems, E.; Herssens, J.; Nuyts, E.; Vanrie, J. Drivers and Barriers for Universal Designing: A Survey on Architects’ Perceptions. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2019, 36, 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, L. Who Are We Building for? Tracing Universal Design in Urban Development. Des. Incl. 2023, 303, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.T.; Levasseur, M. How Does Community-Based Housing Foster Social Participation in Older Adults: Importance of Well-Designed Common Space, Proximity to Resources, Flexible Rules and Policies, and Benevolent Communities. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2023, 66, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sixsmith, J.; Makita, M.; Menezes, D.; Cranwell, M.; Chau, I.; Smith, M.; Levy, S.; Scrutton, P.; Fang, M.L. Enhancing Community Participation through Age-Friendly Ecosystems: A Rapid Realist Review. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levasseur, M.; Dezutter, O.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Babin, J.; Bier, N.; Biron, M.L. Influence of Reading or Writing Activities Shared with Others on Older Adults: Results from a Scoping Study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 44, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeriswyl, M.; Oris, M. Social participation and life satisfaction among older adults: Diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing Soc. 2021, 43, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrbanian, S.; Duquette, P.; Ahmed, S.; Mayo, N.E. Pain Acts through Fatigue to Affect Participation in Individuals living with Multiple Sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, R.; Galeoto, G.; Valente, D.; Conte, A.; Ferrazzano, G.; Leodori, G.; Berardi, A. Fatigue Management Effects on Social Participation and Environment Management in Individuals living with Multiple Sclerosis: Quasi-Experimental Study. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 88, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A. Healthy Aging and Age-Friendly Community Initiatives. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2015, 25, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Black, K.; Buffel, T.; Yeh, J. Community Gerontology: A Framework for Research, Policy, and Practice on Communities and Aging. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbière, M.; Larivière, N. (Eds.) Méthodes Qualitatives, Quantitatives et Mixtes: Dans La Recherche En Sciences Humaines, Sociales et de La Santé, 2nd ed.; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2020; ISBN 978-2-7605-5139-8. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Participants with an average age of at least 50 years |

| Participants living with a disability for an average duration of at least 5 years |

| Studies addressing long-term neurological disabilities resulting from a disorder or event |

| Peer-reviewed primary literature |

| Studies published in English and/or French |

| Studies published since 2000 Studies were included regardless of the presence of comorbidities, provided that the primary focus was on long-term neurological disabilities and social participation |

| Reference Number | Authors (Year) Study Location | Study Design | Study Purpose | Sample Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Bergström et al. (2017) Sweden | Cohort study (quantitative) | Explore and describe the relationship between satisfaction and participation in daily occupations within a Swedish cohort, 5 years post-stroke. | Sample size: N = 69 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 67 years Average time since diagnosis: 5 years |

| [29] | Cattaneo et al. (2017) USA | Cross-sectional study (quantitative) | Estimate the prevalence of participation restrictions in multiple sclerosis according to the level of disability. Evaluate the relationship between participation restrictions, activity limitations, and cognitive deficits. | Sample size: N = 98 Diagnostic: multiple sclerosis Mean age: 53.4 years Average time since diagnosis: 18.2 years |

| [30] | Clarke et al. (2019) USA | Longitudinal study (quantitative) | Examine the environmental barriers and facilitators that hinder or promote participation among adults aging with physical disabilities. | Sample size: N = 1331 Diagnostic: multiple sclerosis (32%); muscular dystrophy (19%); spinal cord injury (23%); post-polio syndrome (26%) Mean age: 64.5 years Average time since diagnosis: 34.6 years |

| [31] | Dalemans et al. (2010) UK | Cross-sectional study (quantitative) | Describe the social participation of individuals living with aphasia. Study the factors related to their level of social participation. | Sample size: N = 150 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 64.2 years Average time since diagnosis: 7.6 years |

| [32] | Dalemans et al. (2010) The Netherlands | Not specified (qualitative) | Explore how individuals living with aphasia perceive their participation in society. Investigate the factors influencing this participation. | Sample size: N = 13 Diagnostic: aphasia post-stroke Mean age: 57.4 years Average time since diagnosis: 5.1 years |

| [33] | D’Alisa et al. (2005) Italy | Not specified (quantitative) | Explore the factors determining “restricted participation”, as measured by the London Handicap Scale, in a selected population of individuals who had a stroke at different times after stroke onset, including very long-term including individuals who had a stroke a long time ago. | Sample size: N = 73 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 62.6 years Average time since diagnosis: 5 years |

| [34] | Gingrich et al. (2023) Canada | Cross-sectional study (quantitative) | Develop an understanding of social participation in individuals who had a stroke using the Behavior Change Wheel model as a guiding theoretical framework. | Sample size: N = 30 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 62.8 years Average time since diagnosis: 9.7 years |

| [35] | Howe et al. (2008) Australia | Exploratory descriptive study (qualitative) | Explore the environmental factors that hinder or support the community participation of adults living with aphasia to develop a valid and reliable environmental factor measurement instrument. | Sample size: N = 25 Diagnostic: aphasia post-stroke Mean age: 62.2 years Average time since diagnosis: 5.6 years |

| [36] | Hoyle et al. (2023) Australia | Exploratory phenomenological study (qualitative) | Explore how personal factors influence the experiences of participation and satisfaction for individuals who had a stroke living in the community. | Sample size: N = 8 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 60.5 years Average time since diagnosis: 9.1 years |

| [37] | Le Dorze et al. (2014) Canada | Not specified (qualitative) | Explore the factors that facilitate or hinder participation according to individuals living with aphasia. | Sample size: N = 17 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 65.7 years Average time since diagnosis: 5.7 years |

| [38] | Lundström et al. (2015) UK | Not specified (qualitative) | Gain an understanding of participation in everyday occupations through the life stories of individuals aging with a traumatic spinal cord injury. | Sample size: N = 8 Diagnostic: traumatic spinal cord injury Mean age: 57.6 years Average time since diagnosis: 27.1 years |

| [39] |

Lundström et al. (2017) Sweden | Cross-sectional cohort study (quantitative) | Describe participation in activities and explore correlations with side effects in individuals aging with a spinal cord injury. | Sample size: N = 73 Diagnostic: traumatic spinal cord injury Mean age: 63.7 years Average time since diagnosis: 36.3 years |

| [40] |

Matérne et al. (2022) Sweden | Cross-sectional study (qualitative) | Explore the experience contributing to participation and resilience to quality of life among individuals who have had a stroke in Sweden. | Sample size: N = 19 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 62.9 years Average time since diagnosis: 6.3 years |

| [41] |

Norlander et al. (2010) Sweden | Grounded theory (qualitative) | Explore conditions influencing long-term participation in social and leisure activities in individuals who had a stroke 15 years ago. | Sample size: N = 10 Diagnostic: stroke Mean age: 72 years Average time since diagnosis: 15 years |

| [42] |

Remillard et al. (2022) USA | Not specified (qualitative) | Understand potential policy gaps related to the personal experiences of individuals aging with a mobility disability and the transportation policies and initiatives designed to support this population in the USA. | Sample size: N = 60 Diagnostic: post-polio syndrome (50%); neurological condition (e.g., MS, cerebral palsy) (18%); accident or event (23%); congenital condition or anomaly (e.g., spina bifida) (7%); other (e.g., adverse drug reaction) (2%) Mean age: 69 years Average time since diagnosis: 19 years |

| [43] |

Savic et al. (2018) UK | Prospective observational cohort study (mixed) | Examine changes in participation levels over a 20-year study period in a cohort of individuals aging with a spinal cord injury and identify potential predictors requiring increased assistance. | Sample size: N = 85 Diagnostic: spinal cord injury Mean age: 67.7 years Average time since diagnosis: 46.3 years |

| [44] |

Sparling et al. (2017) USA | Not specified (quantitative) | Assess the role of access to resources and other determinants in enabling in-person and online social participation. Analyze the association between social participation and the emotional health of individuals living with multiple sclerosis. | Sample size: N = 508 Diagnostic: multiple sclerosis Mean age: 59.2 years Average time since diagnosis: 20.3 years |

| [45] |

Turcotte et al. (2022) Canada | Exploratory descriptive study (qualitative) | Gain an insight into the experiences of aging with a traumatic brain injury. Explore promising intervention avenues for social participation in this population. | Sample size: N = 10 Diagnostic: traumatic brain injury Mean age: 64.9 years Average time since diagnosis: 24.3 years |

| Factors | Articles | Number of Articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal factors | |||

| 1.1. Identity factors | |||

| 1.1.1. Sociodemographic factors | |||

| 1.1.1.1. Younger age | (+) | Dalemans et al. [31] | 1 |

| 1.1.1.2. Older age | (-) | Clarke et al. [30] Hoyle et al. [36] | 2 |

| 1.1.1.3. Identifying as a woman | (+) | Dalemans et al. [31] | 1 |

| 1.1.1.4. More years since diagnosis | (+) | Clarke et al. [30] | 2 |

| (0) | Dalemans et al. [32] | ||

| 1.1.1.5. Never married | (+) | Clarke et al. [30] | 1 |

| 1.1.1.6. Higher education | (+) | Clarke et al. [30] | 1 |

| 1.1.1.7. Low household income | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.2. Personality traits | |||

| 1.1.2.1. Being sociable | (+) | Le Dorze et al. [37] Norlander et al. [41] | 2 |

| 1.1.2.2. Being perseverant | (+) | Hoyle et al. [36] Le Dorze et al. [37] | 2 |

| 1.1.2.3. Being introvert | (-) | Sparling et al. [44] | 2 |

| (?) | Norlander et al. [41] | ||

| 1.1.3. Attitudes | |||

| 1.1.3.1. Being positive | (+) | Le Dorze et al. [37] Norlander et al. [41] | 2 |

| 1.1.3.2. Being motivated | (+) | Dalemans et al. [34] Le Dorze et al. [37] Norlander et al. [41] | 4 |

| 1.1.3.3. Being negative | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.3.4. Avoiding certain activities | (-) | Norlander et al. (2018) [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.3.5. Lacking a sense of belonging | (-) | Dalemans et al. [31] | 1 |

| 1.1.3.6. Feelings of fear | (-) | Hoyle et al. [36] | 1 |

| 1.1.3.7. Being insecure | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.4. Life course | |||

| 1.1.4.1. Activities matching interests | (+) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

| 1.1.4.2. Activities matching individuals’ life stories | (+) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

| 1.1.5. Acceptance and adaptation to disability | |||

| 1.1.5.1. Acceptance of the condition | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.5.2. Not accepting one’s condition | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.5.3. Adaptation to disabilities | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.1.5.4. Use of effective adaptive strategies | (+) | Hoyle et al. [36] | 1 |

| 1.2. Organic system | |||

| 1.2.1. Diagnostic conditions | |||

| 1.2.1.1. Nature of disability | (-) | Clarke et al. [30] Dalemans et al. [31] Matérne et al. [40] | 3 |

| 1.2.2. Mental health comorbidities | (-) | D’Alisa et al. [33] Matérne et al. [40] Norlander et al. [41] Sparling et al. [44] | 4 |

| 1.2.3. Physical dimension | |||

| 1.2.3.1. Good physical functions | (+) | Clarke et al. [30] Dalemans et al. [32] Turcotte et al. [45] | 3 |

| 1.2.3.2. Physical disabilities | (-) | D’Alisa et al. [33] Remillard et al. [42] Savic et al. [43] | 4 |

| (0) | Gingrich et al. [34] | ||

| 1.2.3.3. Pain | (-) | Clarke et al. [30] Norlander et al. [41] Lundström et al. [38,39] | 4 |

| 1.2.3.4. Fatigue | (-) | Clarke et al. [30] Dalemans et al. [32] Matérne et al. [40] Norlander et al. [41] Lundström et al. [38,39] | 6 |

| 1.2.3.5. Sleep problems | (-) | Lundström et al. [38] | 1 |

| 1.2.3.6. Spasticity | (-) | Lundström et al. [39] | 1 |

| 1.2.3.7. Muscle weakness | (-) | Lundström et al. [38,39] | 2 |

| 1.2.3.8. Reduced reflexes | (-) | Remillard et al. [42] | 1 |

| 1.2.3.9. Reduced dexterity | (-) | Remillard et al. [42] | 1 |

| 1.2.3.10. Dizziness | (-) | Matérne et al. [40] | 1 |

| 1.2.4. Cognitive dimension | |||

| 1.2.4.1. Cognitive disabilities | (-) | Cattaneo et al. [29] Norlander et al. [41] Matérne et al. [40] | 3 |

| 1.2.4.2. Concentration problems | (-) | Dalemans et al. [32] | 1 |

| 1.2.4.3. Memory problems | (-) | Dalemans et al. [32] | 1 |

| 1.3. Capability | |||

| 1.3.1. Ability to mobilize environmental resources | (+) | Turcotte et al. [45] Le Dorze et al. [37] | 2 |

| 1.3.2. Intellectual activities | |||

| 1.3.2.1. Adequate knowledge of the condition | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.3.2.2. Problem-solving skills | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] Le Dorze et al. [37] | 1 |

| 1.3.2.3. Planning skills | (+) | Hoyle et al. [36] | 2 |

| (-) | Remillard et al. [42] | ||

| 1.3.3. Motor skills | |||

| 1.3.3.1. Lack of coordination | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 1.3.3.2. Loss of balance | (-) | Cattaneo et al. [29] Dalemans et al. [32] Matérne et al. [40] | 3 |

| 2. Environmental factors | |||

| 2.1. Micro-environments, i.e., personal dimension | |||

| 2.1.1. Social factors | |||

| 2.1.1.1. Supportive social environment | (+) | Bergström et al. [28] Clarke et al. [30] Hoyle et al. [36] Le Dorze et al. [37] Matérne et al. [40] Norlander et al. [41] | 6 |

| 2.1.2. Physical factors | |||

| 2.1.2.1. Adapted technological aids | (+) | Clarke et al. [30] Norlander et al. [41] Lundström et al. [38,39] | 4 |

| 2.1.2.2. Physical barriers to the use of technological aids | (-) | Matérne et al. [40] | 1 |

| 2.2. Meso-environments, i.e., community dimension | |||

| 2.2.1. Social factors | |||

| 2.2.1.1. Accessibility to meaningful community activities | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 2.2.1.2. Familiar environment | (+) | Bergström et al. [28] | 1 |

| 2.2.1.3. Fast-paced community activities | (-) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

| 2.2.1.4. Inaccessible procedures | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] | 1 |

| 2.2.1.5. Discriminatory attitude | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] | 1 |

| 2.2.1.6. Activity costs | (-) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

| 2.2.2. Physical factors | |||

| 2.2.2.1. Accessible environment | (+) | Norlander et al. [41] | 1 |

| 2.2.2.2. Quiet settings | (+) | Dalemans et al. [32] Howe et al. [35] | 2 |

| 2.2.2.3. Opportunities to participate | (+) | Gingrich et al. [34] | 1 |

| 2.2.2.4. Winter | (-) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

| 2.2.2.5. Noisy environment | (-) | Howe et al. [35] | 1 |

| 2.2.2.6. Visually cluttered environments | (-) | Howe et al. [35] | 1 |

| 2.3. Macro environments, i.e., societal dimension | |||

| 2.3.1. Social factors | |||

| 2.3.1.1. Financial and practical government support | (+) | Bergström et al. [28] Matérne et al. [40] | 2 |

| 2.3.1.2. Insufficient government funding | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] Matérne et al. [40] Remillard et al. [42] | 3 |

| 2.3.1.3. Inequitable standardized professional processes | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] Norlander et al. [41] | 2 |

| 2.3.1.4. Unreliability of public and adapted transport services | (-) | Norlander et al. [41] Remillard et al. [42] | 2 |

| 2.3.1.5. Strict policies and regulations related to adapted transport | (-) | Remillard et al. [42] | 1 |

| 2.3.1.6. Lack of knowledge from others | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] | 1 |

| 2.3.2. Physical factors | |||

| 2.3.2.1. Built environment | (-) | Bergström et al. [28] Clarke et al. [30] Howe et al. [35,36] Matérne et al. [40] Norlander et al. [41] Remillard et al. [42] | 7 |

| 2.3.2.2. Geographical distance | (-) | Turcotte et al. [45] | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turcotte, S.; Kheroua, S.; Brun, G.; Gagnon, L.; Bustamante, N.; Labbé, A.; Simard, P.; Veilleux, M.; Lapointe, M.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review. Disabilities 2025, 5, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020049

Turcotte S, Kheroua S, Brun G, Gagnon L, Bustamante N, Labbé A, Simard P, Veilleux M, Lapointe M, Nguyen MH, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review. Disabilities. 2025; 5(2):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020049

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurcotte, Samuel, Sirine Kheroua, Gloria Brun, Laura Gagnon, Nora Bustamante, Angéline Labbé, Pascale Simard, Megan Veilleux, Mia Lapointe, Manh Hung Nguyen, and et al. 2025. "Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review" Disabilities 5, no. 2: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020049

APA StyleTurcotte, S., Kheroua, S., Brun, G., Gagnon, L., Bustamante, N., Labbé, A., Simard, P., Veilleux, M., Lapointe, M., Nguyen, M. H., & Levasseur, M. (2025). Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review. Disabilities, 5(2), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020049