A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motives for Volunteering

1.2. Dynamics of Volunteer Motivation

1.3. Volunteer Satisfaction

1.4. Volunteering in Sports for People with Disabilities

2. Materials and Methods

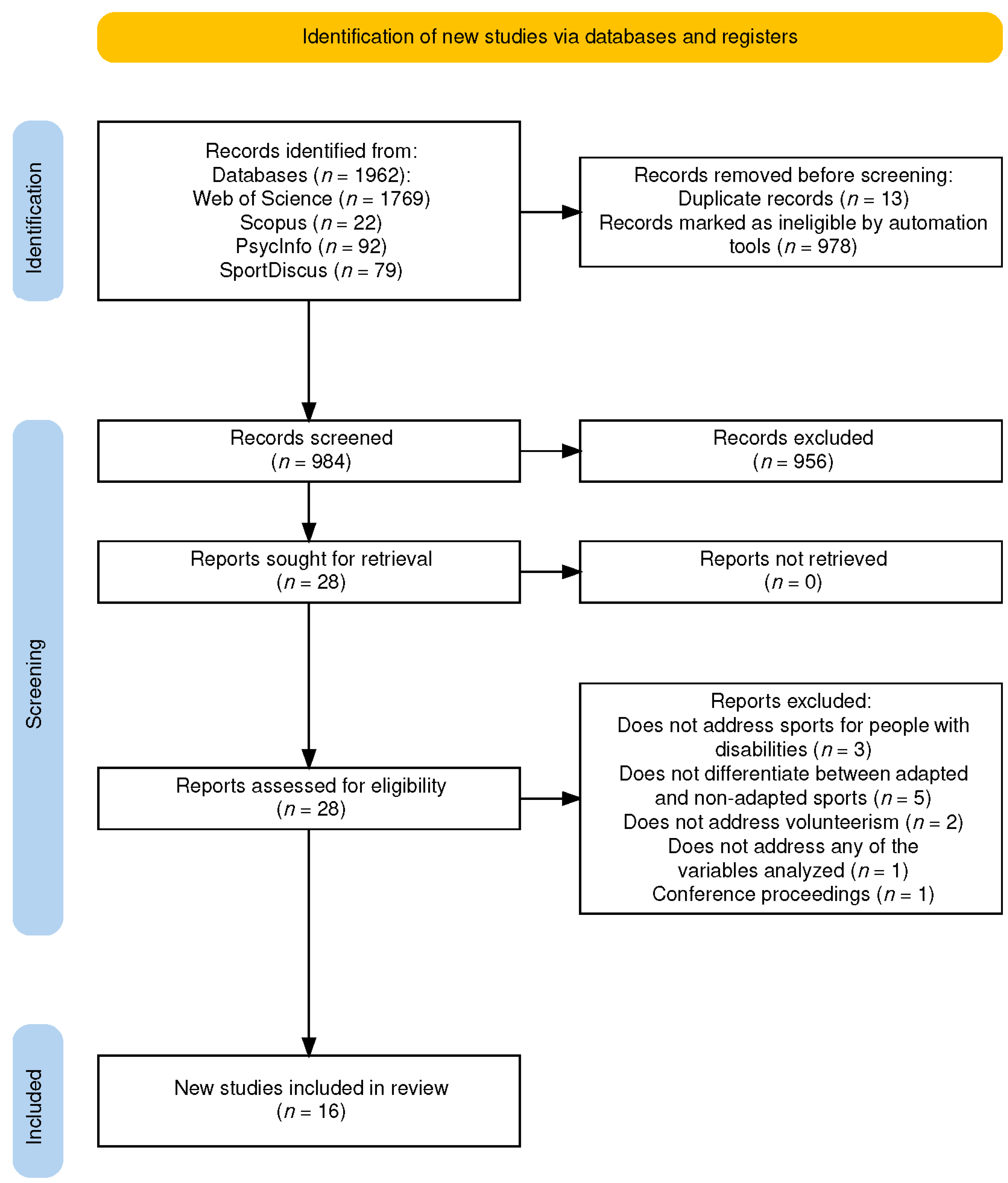

2.1. Data Source and Search Protocol

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Quality Analysis

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

3.3. Type of Volunteering, Contextual Characteristics, and Theoretical Framework

3.4. Characteristics of the Sample

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3.6. Variables and Analysis of the Results

3.6.1. Sports Organizations

3.6.2. Sports Events

3.6.3. Students

4. Discussion

4.1. Geographic and Disciplinary Characteristics

4.2. Methodological and Contextual Approaches

4.3. Motivational Factors

4.4. Barriers and Facilitators

4.5. Satisfaction

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

- Enhancement of volunteer programs to attend volunteers and participant needs. Given the predominance of intrinsic motivation among volunteers, organizations should prioritize personal growth opportunities and emphasize value-based aspects of sports volunteering to increase volunteer satisfaction and retention.

- Development of inclusive policies in sport and/or people with disabilities organizations. The lack of diversity of the types of disabilities suggests a need for developing more inclusive policies and programs that address a broader spectrum of disabilities, extending beyond mental disabilities to those such as deafness or physical disabilities.

- Improve comprehensive training and education. The development and adequate training and education for both staff and volunteers is needed to underscore the importance of implementing volunteer training programs to improve the quality of volunteer engagement and the effectiveness of sports programs for people with disabilities.

- Promotion of interdisciplinary research. Encouraging interdisciplinary research and collaboration could expand the scope of knowledge and facilitate the integration of different research fields such as sports management, psychology, social work, studies about disabilities, or volunteerism.

- Mitigation of barriers to increase participation among people with disabilities. Identifying and addressing barriers to participation, such as interpersonal and structural factors, could enhance accessibility for people with disabilities in the sport volunteering programs, benefiting inclusivity.

- Integration of volunteer competences recognition for career development. While intrinsic factors are predominant, incorporating a recognition of the competencies developed by each volunteer could enhance their career development opportunities and could attract a broader audience to volunteer.

- Integrate cultural sensitivity in sports volunteers program design. Considering cultural differences in motivation, organizations should structure their volunteer programs to align with the cultural contexts of their volunteers, potentially increasing engagement and effectiveness.

- Using mixed-methods insights in the assessment of sports volunteering programs. The valuable insights gained from qualitative studies highlight the importance of analyzing it together with surveys to have a better understanding of the emotional and motivational issues of volunteers to design more empathetic and supportive volunteer environments.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Year | Location | Journal | Type of Volunteer | Type of Organization | Type of Disability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collier et al. [79] | 2015 | USA | Therapeutic Recreation Journal | Organization volunteers | Sport or recreation organizations | Different types of disabilities |

| Epiney et al. [9] | 2023 | Switzerland | PLoS ONE | Organization volunteers | Disabled organization | Severe mental health disorders |

| Grimaldi-Puyana et al. [77] | 2018 | Spain | Materiales para la historia del deporte | Organization volunteers | Sport or recreation organization | Intellectual disabilities |

| Kappelides and Spoor [68] | 2018 | New Zealand | Sport Management Review | Organization volunteers | Sport or recreation organizations | Intellectual disabilities |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [32] | 2011 | Malaysia | Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly | Event volunteers | National Sport Event | Intellectual disabilities |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [33] | 2007 | Malaysia | Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development | Students | International sport event | Different types of disabilities |

| Khoo et al. [31] | 2011 | Malaysia | African Journal of Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance | Event volunteers | National and international sport event | Different types of disabilities |

| Kim et al. [83] | 2010 | Korea | European Sport Management Quaterly | Event volunteers | National sport event | Intellectual disabilities |

| Kumnig et al. [84] | 2014 | Austria | Voluntas | Event volunteers | International sport event | Intellectual disabilities |

| Labbe et al. [87] | 2019 | England | Leisure Sciences | Organization volunteers | Disabled organization | Physical disabilities |

| Nieto et al. [78] | 2015 | Spain | Anales de Psicología | Students | University | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| Rodrigues and Soares [85] | 2020 | Portugal | Revista Intercontinental de Gestão Desportiva | Event volunteers | International sport event | Different types of disabilities |

| Sanders and Balcanoff [66] | 2021 | USA | Disability and Rehabilitation | Organization volunteers | Care organization | Different types of disabilities |

| Surujlal [65] | 2010 | South Africa | African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance | Event volunteers | National and international sport event | NR |

| Wekesser et al. [80] | 2023 | USA | Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly | Students | Sport or recreation organizations | Physical disabilities |

| Wu et al. [86] | 2015 | China | Voluntas | Students | National sport event | Intellectual disabilities |

| Authors | Year | Sample | Male (%) | Female (%) | Average Age | University Studies (%) | Student (%) | Marital Status (% Single) | Marital Status (% Married) | Occupation (% Workers) | Previous Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collier et al. [79] | 2015 | 63 | 39 | 61 | 31 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Epiney et al. [9] | 2023 | 15 | 47 | 53 | 36 | 60 | 20 | NR | NR | NR | 4 years |

| Grimaldi-Puyana et al. [77] | 2018 | 112 | 47.2 | 52.8 | NR | 45.4 | NR | 55.7 | 33.3 | NR | NR |

| Kappelides and Spoor [68] | 2018 | 10 | 60 | 40 | 18–64 | 60 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 years |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [32] | 2011 | 289 | 35 | 65 | 20− (6.0%); 20–39 (16%); 40–59 (54.0%); 60+ (24.0%) | 70.2 | NR | NR | NR | 57 | 100 |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [33] | 2007 | 301 | 38.2 | 61.8 | 21 | NR | 97 | NR | NR | NR | 13.3 |

| Khoo et al. [31] | 2011 | 742 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 33.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 46.4 |

| Kim et al. [83] | 2010 | 224 | 33.9 | 66.1 | 18–25 (16.8%); 26–30 (14.9%); 31–55 (57.9%); 55–65 (9.3%); 66+ (0.9%) | 87.5 | NR | 11.8 | 88.2 | 86.5 | NR |

| Kumnig et al. [84] | 2014 | 167 | 22.3 | 77.7 | 25.1 | 83.3 | NR | 38.8 | 61.2 | NR | NR |

| Labbe et al. [87] | 2019 | 18 | 67 | 33 | 20–70 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nieto et al. [78] | 2015 | 230 | 11 | 89 | NR | 0 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Rodrigues and Soares [85] | 2020 | 74 | 39.2 | 60.8 | 34.6 | 27 | 36 | 56 | 16 | 10 | 39.2 |

| Sanders and Balcanoff [66] | 2021 | 48 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 31.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 13 | 4.5 years |

| Surujlal [65] | 2010 | 152 | 27 | 73 | 32.1 | 59.2 | NR | NR | NR | 62.4 | 93 |

| Wekesser et al. [80] | 2023 | 105 | 29.5 | 70.5 | 24.3 | 0 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wu et al. [86] | 2015 | 180 | 30 | 70 | 20.64 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Authors | Year | Method | Variables | Tool | Theory | Data Analysis | Results | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collier et al. [79] | 2015 | Quantitative | Motivation; Comfort; Future intentions; Societal attitudes | VFI | Social Cognitive Theory | Descriptive; Comparative | Motivation: Higher scores for values (29), understanding (28), and enhancement (24). Lower scores for career (19) and protective (18). The volunteer experiences reported increased comfort levels and more positive perceptions of people with disabilities. Interaction with DP significantly improves the feeling of reward when helping, comfort with the interaction, and noticing the person more than the disability. Social attitudes towards people with ASD improved in the post-assessment compared to the pre-assessment, especially when perceiving a higher level of communication and feeling of comfort with the person with ASD. | Volunteering in therapeutic recreation programs can positively influence volunteers’ comfort levels and attitudes towards people with disabilities. Volunteers were primarily driven by altruistic motives and a desire for personal growth. |

| Epiney et al. [9] | 2023 | Qualitative | Perceptions; Motivation; Participation Barriers; Participation Facilitators; Personal outcomes | Interview | Competence model | Thematic analysis (deductive coding) | Motivation: (i) for others: promoting IMHD physical activities (60%), enabling IMHD to succeed (33%), doing something meaningful (47%); (ii) for themselves: enjoying the activity (73%), gaining experience and skills (60%). Challenges and barriers: (i) intrapersonal: mental state (73%), motivation/apathy (73%), physical fitness (53%), medication side effects (33%); (ii) structural: timing and location of sports programs (40%); (iii) interpersonal: group composition (53%); (47%), social support (60%); (iv) external social support: support from immediate environment (47%); (v) sports program: appropriate level of difficulty (47%), gratification (87%), personal development (73%), witnessing participants’ success (47%). Results for coaches: satisfaction and gratification (87%), personal development (73%), witnessing the success of participants (47%). | The study identified various challenges and barriers to participation in voluntary sport programs for people with mental health disorders, including intrapersonal, structural and interpersonal factors. Facilitators of participation included the role of coaches, group cohesion, external social support and appropriate sport programs. Personal characteristics of coaches, such as professional experience, methodological expertise, self-experience and social skills, were crucial to the success of the programs. Coaches were motivated by both altruistic reasons and personal benefits, and reported positive outcomes from their participation, including satisfaction, witnessing participants’ success and personal development. The study emphasizes the need for specialized training and support for coaches working with people with mental health disorders in sport settings. |

| Grimaldi-Puyana et al. [77] | 2018 | Quantitative | Recognition; Responsibility with tasks; Physical conditions; Rewards; Satisfaction | NR | NR | Descriptive | Volunteers and workers are moderately satisfied with their activity and their extrinsic motivation, but their intrinsic motivation is moderately high. Workers reported high satisfaction compared with volunteers. | The high number of workers who carry out their activity as volunteers and without related qualifications in the population of this study shows the need to regulate the sports sector. This lack of regulation in the labor market will continue to incorporate poorly qualified professionals, and consequently could harm sports services for athletes with intellectual disabilities. |

| Kappelides and Spoor [68] | 2018 | Qualitative | Benefits; Barriers; Challenges; Potential solutions | NR | NR | Descriptive | Incorporating volunteers with a disability has several benefits including social acceptance, social inclusion and personal development. Some barriers to volunteering are identified including negative attitudes, personal factors, organizational factors and lack of social inclusion. | The organizations need to create an environment that facilitates open, two-way communication with volunteers with a disability about their needs and wants. The organizations should be training and educating all volunteers and staff around an inclusive workplace culture. |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [32] | 2011 | Quantitative | Motivation | SEVMS | NR | EFA; Multivariant | Motivation scores: Purposive (4.26); Solidary (3.42); Commitments (2.68); Family Tradition (2.58); External Traditions (2.54). | Males are high punctuation in Family Traditions and External Traditions, while female are high scores in purposive and commitments. |

| Khoo and Engelhorn [33] | 2007 | Quantitative | Motivation | SEVMS | NR | EFA | Motivation scores: Solidary (4.37); Purposive (4.36); Commitment (3.77); Free Time (3.34); Family Tradition (2.47) | NR |

| Khoo et al. [31] | 2011 | Quantitative | Motivation | SEVMS | NR | Comparative | Malasia motivation score: Solidary (4.48); Purposive (4.23); Commitments (3.71); External Traditions (3.02) South Africa motivation score: Solidary (4.05); Purposive (4.05); Commitments (3.14); External Traditions (2.61) USA motivation score: Purposive (3.84); Solidary (3.39); Commitments (2.61); External Traditions (2.43) | Several motivational items show differences between countries. |

| Kim et al. [83] | 2010 | Quantitative | Motivation | Modified VFI | NR | CFA; Multivariant; Comparative | Motivation scores: Value (6.25), Understanding (5.62), Social (4.50), Career (3.52), Protective (3.25), Enhancement (4.74) | Values and Understanding are the two factors most evaluated according with the previous literature. Volunteers in the special-needs event had higher motivation in all six factors than the national and local event. Like the international event, the special-needs event might be considered to a great opportunity for volunteering. |

| Kumnig et al. [84] | 2014 | Quantitative | Motivation | MVS | Integrated conceptual framework and consistency theory | Regression | Motivation scores: Value (5.20); Understanding (4.73); Personal Development (4.59); Community Concern (4.02); Steam Enhancement (2.40) | Volunteers with high psychological well-being report high values in Value and Understanding and low values in Esteem, Enhancement and Community Concern. |

| Labbe et al. [87] | 2019 | Qualitative | Participation; Commitment; Drop-out | Interview | NR | Analysis of data collection, describing the discourse of participants | Two main themes were identified. (1) “Anchors away: reasons for setting sail”, described the benefits of adaptive sailing including learning opportunities, leaving disability onshore, challenging stigma, building a community and engaging with nature. (2) “Running ashore: challenges with program delivery and logistics”, acknowledged the various issues encountered, including issues around accessibility, equipment, scheduling, safety management, and volunteers/volunteering. Volunteers note the benefits for people with disabilities, the barriers of space and materials for practice, the importance of support and that much remains to be done. | The benefits that sailors with disabilities derived from their involvement in adaptive sailing, showed how outdoor leisure can have a positive psychological and social impact on people with disabilities. The identified barriers to outdoor leisure activities that people with disabilities may encounter, the facilitators may provide insights for the policies and practices that support access. |

| Nieto et al. [78] | 2015 | Quantitative | Motivation; Satisfaction | Motivation and satisfaction—APUNTATE Impact Ques-tionnaire for Volunteers | NR | Descriptive; Comparative | The main reason volunteers stated for enrolling in this program was to help others in 70% (n = 98) of the cases. The remaining 30% stated that they enrolled to improve their own training. The overall satisfaction with the program stated by the volunteers was very high for 50.9% of them and quite high for 43.9%. No significant differences were found in the compensation between satisfaction and the type of degree/main motivation. | The perceived impact of volunteers is closely linked to the level of organization of the program, the most valuable being: (a) the program provides ongoing training and support; (b) the program facilitates long-term contact with people with ASD and their environment; (c) the program offers the opportunity to learn to anticipate and respond appropriately to the needs and preferences of the people they support; (d) formal and informal recognition of volunteering improves their employment prospects. Volunteers perceived that their participation had a very high impact on their personal development, their social and communication skills, their professional development and their perception of their social contribution. The results of this study clearly suggest that the success and effectiveness of volunteer programs supporting the leisure of people with ASD depend on several factors related to both the design of the supports provided and the structure of the program itself. |

| Rodrigues and Soares [85] | 2020 | Quantitative | Motivation; Satisfaction; Future intention | Downward & Ralston Survey | NR | Descriptive; Comparative; Correlation; Regression | Motivation scores: Highest values: Personal experience (3.86), Community involvement (3.71), Personal development (3.31). Lowest values: Tradition of volunteering (2.35), Opportunity to work (2.46). Satisfaction: Most stated that they were satisfied, very satisfied or extremely satisfied (17.1%, 25.7% and 37.1%, respectively). Future intentions: 75.8% stated that they would be willing to repeat the volunteering experience. | Significant differences in Job Opportunity, Volunteering Tradition, Esteem, Egoism between pre- and post-evaluation. Job opportunities and volunteering tradition were devalued after the event, while self-esteem and egoism were valued more. The organization of the adaptive sport event played a crucial role in promoting learning, personal development, and community participation. Despite the lack of a strong volunteering culture among participants, the event fostered a high degree of satisfaction and a willingness to volunteer again in the future. |

| Sanders and Balcanoff [66] | 2021 | Mixed methods | Motivation; Experience; | VFI, Interview | Functional Theory | Quantitative: Descriptive; Comparative; Correlation Qualitative: Thematic analysis (deductive coding) | Volunteers in the adapted skiing program were driven by a mix of personal and professional motives. While altruistic values, personal growth, and learning about the participants were key for all volunteers, college students placed a higher value on career-related benefits and gaining experience in their field. Volunteers found the experience rewarding and emphasized the importance of seeing the children’s progress, the positive emotional connections formed, and the opportunity to apply their skills and to learn from others. | Recommendations to improve volunteering: (i) expand training opportunities; (ii) develop interprofessional opportunities for collaboration in other fields; (iii) improve communication systems related to logistics. Motivations for volunteering are multidimensional and may be related to the ages and life stages of volunteers. Experienced volunteers were motivated by their values to serve beneficiaries, but appreciated social interaction with younger volunteers, mentoring opportunities, and outdoor fun. Significant differences in motivational factors were greater in students than in long-term volunteers. Recognizing both personal and professional motivators is essential for effective recruitment, program development, and fostering interprofessional collaboration within adaptive sports programs. |

| Surujlal [65] | 2010 | Quantitative | Motivation | SEVMS | NR | Descriptive; EFA | Motivation scores: Altruism (4.39), Interaction and achievement (4.05), Diversion (3.80), External influence and free time (2.62). Less than 20% of volunteers expected to be rewarded for their participation. | The results also showed that the decision to volunteer was a personal one that was not based on external factors. The research highlights the importance of altruism and self-improvement as key motivators for volunteers in the context of disability sporting events in South Africa. It also highlights the importance of creating opportunities for volunteers to learn, grow and feel fulfilled through their contributions. |

| Wekesser et al. [80] | 2023 | Qualitative | Experience; Motivation; Program impact | Interview | NR | Descriptive statistics Thematic analysis (inductive coding) | Seven major themes were developed relative to participants’ perceptions of their volunteer experiences: (a) volunteer motivation; (b) diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI); (c) program design and practice experience; (d) challenges; (e) relationship building; (f) personal and professional growth; and (g) transformative experience. | Participants described different motivations that led them to make the decision to volunteer, from intrinsic (e.g., fun) to extrinsic (e.g., to boost their resume). In the program, volunteers had ample opportunities to socialize with both non-disabled volunteers and people with disabilities, were regularly challenged, and were influenced by a unique program design and hands-on experience. All these processes occurred in a program environment that fostered DEI values. This process of growth and learning sparked a volunteer’s transformative experience, which in some cases, resulted in more intrinsic reasons to continue participating. |

| Wu et al. [86] | 2015 | Quantitative | Competence; Motivation; Satisfaction; Future intention | NR | Self-determination Theory | CFA | Intrinsic motivation (5.87), Satisfaction (6.29), Future intentions (6.20) | Intrinsic motivation was a partial mediator for the relationship between competence and job satisfaction. Job satisfaction positively influenced intention, and it acted as a full mediator in the relationship between intrinsic motivation and intention. |

Appendix B

| Item | Section/Topic and Checklist Item | Collier et al. [79] | Grimaldi-Puyana et al. [77] | Khoo and Engelhorn [33] | Khoo and Engelhorn [32] | Khoo et al. [31] | Kim et al. [83] | Kumming et al. [84] | Nieto et al. [78] | Rodrigues and Soares [85] | Surujlal [65] | Wu et al. [86] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | ||||||||||||

| 1a | Identification of the type of study in the title | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1b | Structured summary of objective, methods, results, and conclusions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Introduction | ||||||||||||

| Background and Objetives | ||||||||||||

| 2a | Scientific backgrounf and explanation of rationale | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Methods | ||||||||||||

| Participants | ||||||||||||

| 3a | Eligibility criteria for participants | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3c | A table showing baseline demographic characteristics | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sample Size | ||||||||||||

| 4a | The sample size has been determined | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4b | When applicable, explanation of how sample size was determined | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Procedure | ||||||||||||

| 5 | The procedure has sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Instrument or Tools | ||||||||||||

| 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when the were assessed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6b | Use of validity and reliability tools. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Implementation | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Who made each part of study | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Statistical Methods | ||||||||||||

| 8a | Statistical methods used to analyse the results | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8b | Use of Methods for additional analyses to objective of study | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Results | ||||||||||||

| Outcomes and Estimation | ||||||||||||

| 9 | A table or figure showing outputs of analysis more relevant of study | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Discussion | ||||||||||||

| Interpretation | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Limitations | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Study limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecisions, etc. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Practisal Implication | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Main applicability to results of study | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other Information | ||||||||||||

| Funding | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Sources of funding and other support, role of funders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL SCORE (Max. 20 points) | 13 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 13 | |

| Item | Section/Topic and Checklist Item | Epiney et al. [9] | Kappelides and Spoor [68] | Labbé et al. [87] | Wekesser et al. [80] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | |||||

| 1a | Identification of the type of study. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1b | Overview structured in objective, method, results and conclusions. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Introduction | |||||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of the relevant rationale or theories. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Method | |||||

| 3a | Qualitative approach and research paradigm. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3b | Researcher characteristics and reflexivity | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3c | Context—settings and factors | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3d | Sampling strategy. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3e | Ethical issues—consent | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3f | Data collection—procedural details. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3g | Data collection instruments and technologies. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3h | Units of study—number and relevant characteristics of participants or documents. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3i | Data processing—transcription, management, security, integrity, data integrity, data coding and anonymisation. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3j | Data analysis with specific focus. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3k | Techniques to improve the reliability and credibility of data analysis. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Results | |||||

| 4a | Data synthesis and interpretation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4b | Link to empirical data—evidence, citations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Discussion | |||||

| 5a | Integration with previous work, implications, transferability and contributions. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5b | Limitations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | |||||

| 6a | Conclusions and potential sources of influence. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6b | Sources of funding and other support. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| TOTAL SCORE (Max. 21 points) | 17 | 17 | 20 | 18 | |

| Item | Section/Topic and Checklist Item | Sanders and Balcanoff [66] |

|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | ||

| 1a | Identification of the type of study. | 1 |

| 1b | Overview structured in objective, method, results and conclusions. | 1 |

| Introduction | ||

| Rationale and objectives | ||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of the rationale. | 1 |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses. | 1 |

| Method | ||

| Quantitative section | ||

| 3a | Eligibility criteria for participants. | 0 |

| 3b | Settings and locations where data were collected. | 1 |

| 3c | A table of baseline demographic characteristics. | 0 |

| Sample size | ||

| 3d | Sample size has been determined | 0 |

| 3e | If applicable, explanation of how the sample size was determined. | 0 |

| Procedure | ||

| 3f | The procedure has sufficient detail to allow replication, including how and when they were administered. | 1 |

| Instruments or tools | ||

| 3g | Fully defined primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed. | 1 |

| 3h | Use of validity and reliability tools. | 1 |

| Implementation | ||

| 3i | Who did each part of the study. | 0 |

| Statistical methods | ||

| 3j | Statistical methods used to analyse the results | 1 |

| 3k | Use of methods of analysis additional to the purpose of the study | 0 |

| Qualitative section | ||

| 3l | Qualitative approach and research paradigm | 0 |

| 3m | Researcher characteristics and reflexivity | 0 |

| 3n | Context—settings and factors | 1 |

| 3ñ | Sampling strategy | 1 |

| 3o | Ethical issues—consent | 1 |

| 3p | Data collection—procedural details | 1 |

| 3q | Data collection instruments and technologies. | 1 |

| 3r | Units of study—number and relevant characteristics of participants or documents. | 1 |

| 3s | Data processing—transcription, management, security, integrity, data integrity, data coding and anonymity. | 0 |

| 3t | Data analysis with specific focus. | 1 |

| 3u | Techniques to improve the reliability and credibility of data analysis. | 0 |

| Results | ||

| Quantitative section | ||

| 4a | A table or figure showing the results of the most relevant analyses of the study. | 1 |

| Qualitative section | ||

| 4b | Synthesis and interpretation of data. | 1 |

| 4c | Link to empirical data—evidence, citations. | 1 |

| Discussion | ||

| Interpretation | ||

| 5a | Interpretation consistent with results, implications, transferability and contributions. | 1 |

| Limitations | ||

| 5b | Limitations of the study. | 1 |

| Conclusions | ||

| 6a | Main applicability of the study results. | 1 |

| 6b | Practical applications | 0 |

| Other | ||

| Funding | ||

| 7 | Sources of funding and other support, role of funders | 0 |

| TOTAL SCORE (Max. 34 points) | 21 | |

References

- Ortiz, A.Y.; Henriques Veiga, F. Relaciones Entre Creencias Motivacionales y Actitudes Frente al Voluntariado: Un Estudio Con Jóvenes Universitarios En Portugal. In Proceedings of the Atas do XII Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Volunteers (UNV) Programme. 2022 State of the World’s Volunteerism Report: Building Equal and Inclusive Societies; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://swvr2022.unv.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/UNV_SWVR_2022.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Participation in Formal Volunteering: Percentage of the Working-Age Population Who Declared Having Volunteered Through an Organisation at Least Once a Month, over the Preceding Year, Around 2012. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/how-s-life-2017_how_life-2017-en.html (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Education Youth, Sport and Culture. In Sport and Physical Activity–Full Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c601d8fb-3e0d-11ed-92ed-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Lockstone-Binney, L.; Holmes, K.; Smith, K.; Baum, T. Volunteers and Volunteering in Leisure: Social Science Perspectives. Leis. Stud. 2010, 29, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Volunteers (UNV) Programme. Annual Report 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unv.org/Annual-report/Annual-Report-2019 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- United Nations A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2015. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3923923/files/A_RES_70_1-EN.pdf?ln=es (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Rochester, C. Trends in Volunteering. In The Routledge Handbook of Volunteering in Events, Sport and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 460–472. ISBN 978-0-367-81587-5. [Google Scholar]

- Epiney, F.; Wieber, F.; Loosli, D.; Znoj, H.; Kiselev, N. Voluntary Sports Programs for Individuals with Mental Health Disorders: The Trainer’s View. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno, J.M.; Tsolakis, A. Profundizar En El Voluntariado: Los Retos Hasta 2020; Plataforma del Voluntariado de España: Madrid, Spain, 2012; Available online: https://www.fresnoconsulting.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/3_2012_profundizar_voluntariado_retos2020-3.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Hodgkinson, V.A. Volunteering in Global Perspective. In The Values of Volunteering; Dekker, P., Halman, L., Eds.; Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 35–53. ISBN 978-1-4615-0145-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X. Inspiring Sport Event Volunteer Engagement and Sense of Pride: The Importance of Organisational Environmental Factors. Leis. Stud. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.C. Principles of Modern Management: Functions and Systems, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; ISBN 0-205-11677-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, H.; Ross, S.D. Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction. J. Venue Event Manag. 2009, 1, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Fredline, L.; Cuskelly, G. Heterogeneity of Sport Event Volunteer Motivations: A Segmentation Approach. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Tang, Y. Knowledge Mapping of Volunteer Motivation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Cross-Cultural Comparative Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Chambers, S.K.; Hyde, M.K. Systematic Review of Motives for Episodic Volunteering. Voluntas 2016, 27, 425–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, F.; Gutiérrez, G.; Sauto, V. Volunteer Functions Inventory: A Systematic Review. Psicothema 2017, 29, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. A Systematic Review of Motivation of Sport Event Volunteers. World Leis. J. 2018, 60, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angosto, S.; Bang, H.; Bravo, G.A.; Díaz-Suárez, A.; López-Gullón, J.M. Motivations and Future Intentions in Sport Event Volunteering: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyatta, G.N.; Zani, A.P. An Evaluation of the Motives behind Volunteering and Existing Motivational Strategies among Voluntary Organizations in Kenya. Res. Human. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Clary, E.G.; Snyder, M.; Ridge, R.D.; Copeland, J.; Stukas, A.A.; Haugen, J.; Miene, P. Understanding and Assessing the Motivations of Volunteers: A Functional Approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Kim, S.-B.; Kim, D.-Y. Segmenting Volunteers by Motivation in the 2012 London Olympic Games. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntert, S.T.; Neufeind, M.; Wehner, T. Motives for Event Volunteering: Extending the Functional Approach. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Giannoulakis, C.; Scott, B.F.; Felver, N.; Judge, L.W. Gender Differences in Motivation, Satisfaction, and Retention of Sport Management Undergraduate Student Volunteers. Indiana Assoc. Health Phys. Edu. Rec. Dance 2016, 45, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.E.; Giannoulakis, C.; Felver, N.; Judge, L.W.; David, P.A.; Scott, B.F. Motivation, Satisfaction, and Retention of Sport Management Student Volunteers. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2017, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-B.; Alexander, A.; Kim, D.-Y. Volunteers’ Motivation, Satisfaction, and Intention to Volunteer in the Future: The London 2012 Olympic Games. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2019, 31, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D.; Johnson, J.; Felver, N.; Wanless, E.; Judge, L.; State, B. Influence of Volunteer Motivations on Satisfaction for Undergraduate Sport Management Students. Glob. Sport Bus. J. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Zhang, J.J.; Connaughton, D. Modification of the Volunteer Functions Inventory for Application in Youth Sports. Sport Manag. Rev. 2010, 31, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.M.; Johnston, M.E.; Twynam, G.D. Volunteer Motivation, Satisfaction, and Management at an Elite Sporting Competition. J. Sport Manag. 1998, 12, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.; Surujlal, J.; Engelhorn, R. Motivation of Volunteers at Disability Sports Events: A Comparative Study of Volunteers in Malaysia, South Africa and the United States. Afr. J. Phys. Health Edu. Rec. Dance 2011, 17, 356–371. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, S.; Engelhorn, R. Volunteer Motivations at a National Special Olympics Event. Adapt. Physical Activ. Q. 2011, 28, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.; Engelhorn, R. Volunteer Motivations for the Malaysian Paralympiad. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2007, 4, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockstone-Binney, L.; Holmes, K.; Smith, K.; Baum, T.; Storer, C. Are All My Volunteers Here to Help Out? Clustering Event Volunteers by Their Motivations. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angosto, S.; Vegara-Ferri, J.M.; Bravo, G. Motivational profiles of university volunteers in sport events: A segmentation approach. CCD 2021, 16, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Benson, A.M.; Blackman, D.A.; Terwiel, A.F. It’s All About the Games! 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games Volunteers. Event Manag. 2013, 17, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Pentifallo, C. Ensuring Volunteer Impact, Legacy and Leveraging Is Not “Fake News”: Lessons from the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 683–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Edwards, D.; Terwiel, F.A. Sport Mega-Event Volunteers’ Motivations and Postevent Intention to Volunteer: The Sydney World Masters Games, 2009. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Benson, A. Volunteers with Disabilities at the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Who, Why, and Will They Do It Again? Event Manag. 2017, 21, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Chelladurai, P. Development and Validation of the Volunteer Motivations Scale for International Sporting Events (VMS-ISE). Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2009, 6, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Alexandris, K.; Ross, S.D. Validation of the Revised Volunteer Motivations Scale for International Sporting Events (VMS-ISE) at the Athens 2004 Olympic Games. Event Manag. 2009, 12, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Bravo, G.A.; Mezzadri, F.M.; Figuerôa, K.M. The Impact of Volunteer Experience at Sport Mega-events on Intention to Continue Volunteering: Multigroup Path Analysis. J. Commun. Psychol. 2019, 47, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Downward, P.; Dickson, G. Factors Influencing Time Allocation of Sport Event Volunteers. Int. J. Event Fest. Manag. 2018, 9, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Zehrer, A.; Fairley, S.; Rossi, L. Gender and Volunteering at the Special Olympics: Interrelationships Among Motivations, Commitment, and Social Capital. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Cuskelly, G.; Fredline, L. Motivation and Psychological Contract in Sport Event Volunteerism: The Impact of Contract Fulfilment on Satisfaction and Future Behavioral Intention. Event Manag. 2020, 24, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.A.; Cavalcante, C.E. Medalha de ouro! Estudo sobre motivação no trabalho voluntário eventual nos Jogos Olímpicos no Rio de Janeiro. Organ. Cont. 2018, 14, 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Vetitnev, A.; Bobina, N.; Terwiel, F.A. The Influence of Host Volunteer Motivation on Satisfaction and Attitudes Toward Sochi 2014 Olympic Games. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.S.-K.; Kim, M.; Zhang, J.J. Assessing Volunteer Satisfaction at the London Olympic Games and Its Impact on Future Volunteer Behaviour. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1864–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Skokie, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Hoye, R.; Cuskelly, G. The Psychology of Sport Event Volunteerism: A Review of Volunteer Motives, Involvement and Behaviour. In People and Work in Events and Conventions: A Research Perspective; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 171–180. ISBN 978-1-84593-476-7. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Kuhn, R.; Guzley, R.M. The Volunteer Satisfaction Index. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2002, 28, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boezeman, E.J.; Ellemers, N. Intrinsic Need Satisfaction and the Job Attitudes of Volunteers versus Employees Working in a Charitable Volunteer Organization. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 2009, 82, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. An Integrated Model of Volunteers’ Motivations, Interpersonal Exchange and Behavioral Intentions: A Case of Event Volunteers. Doctoral Dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chelladurai, P. Human Resource Management in Sport and Recreation; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7360-5588-8. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, M.A. Volunteer Satisfaction and Volunteer Action: A Functional Approach. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2008, 36, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Reisinger, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Yoon, S.-M. The Influence of Volunteer Motivation on Satisfaction, Attitudes, and Support for a Mega-Event. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Won, D.; Bang, H. Why Do Event Volunteers Return? Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Market. 2014, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angosto, S.; Díaz-Suárez, A.; López-Gullón, J.M. Motivation and Satisfaction in University Sports Volunteering. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2023, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Kang, H.; Cho, H. The Relationship between Volunteer Management, Satisfaction, and Intention to Continue Volunteering in Sport Events: An Environmental Psychology Perspective. Nonprofit Manag. Lead. 2024, 35, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaie, S.; Badri Azrin, Y.; Abdavi, F.; Khodadadi, M.R.; Hoseini, M.D. A Pattern Approach of Sports Volunteers at 2022 the 15th Cultural-Sports Olympiad in Iran: Motivations and Satisfaction Sports Volunteer and Intention to Continue. RSMM 2024, 5, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Ruetz, J.; Feiler, S.; Breuer, C. Non-Profit Sports Club Volunteers: Same, Same, but Different or One and the Same? Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Corrales, J.; Huertas-Hoyas, E.; García-Bravo, C.; Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Volunteering as a Meaningful Occupation in the Process of Recovery from Serious Mental Illness: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7602205090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Suárez, M.; Olmos-Gómez, M.D.C.; Castán-García, M.; Portillo-Sánchez, R. Promoting Emotional and Social Well-Being and a Sense of Belonging in Adolescents through Participation in Volunteering. Healthcare 2021, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kang, H.-K. How Do Compulsory Volunteer Experiences at Sporting Events Help Improve Sport Participation and Life Satisfaction? Leis. Sci. 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surujlal, J. Volunteer Motivation in Special Events for People with Disabilities. Af. J. Phys. Health Edu. Rec. Dance 2010, 16, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.; Balcanoff, S. Motivations for Volunteering in an Adapted Skiing Program: Implications for Volunteer Program Development. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 7087–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombás, J. Sighted Volunteers’ Motivations to Assist People with Visual Impairments in Freetime Sport Activities. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2013, 8, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappelides, P.; Spoor, J. Managing Sport Volunteers with a Disability: Human Resource Management Implications. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Büttner, F.; Andrade, R.; Weir, A.; Ashe, M.C.; Holden, S.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Delahunt, E.; Dijkstra, H.P.; Mathieson, S.; et al. Implementing the 27 PRISMA 2020 Statement Items for Systematic Reviews in the Sport and Exercise Medicine, Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation and Sports Science Fields: The PERSiST (Implementing Prisma in Exercise, Rehabilitation, Sport Medicine and SporTs Science) Guidance. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Llerena, A.; Angosto, S.; Pérez-Campos, C.; Alcaraz-Rodríguez, V. A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations. 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/z3wsp (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angosto, S.; García-Fernández, J.; Valantine, I.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M. The Intention to Use Fitness and Physical Activity Apps: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Cuskelly, G. A Systematic Quantitative Review of Volunteer Management in Events. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Alcaraz-Rodríguez, V. Análisis y diferencias en satisfacción laboral de los recursos humanos y voluntarios con deportistas con discapacidad intelectual. Mat. Hist. Dep. 2018, 16, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, C.; Murillo, E.; Belinchón, M.; Giménez, A.; Saldaña, D.; Martínez, M.-Á.; Frontera, M. Supporting People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Leisure Time: Impact of an University Volunteering Program and Related Factors. Anal. Psicol. 2015, 31, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Collier, V.; Rothwell, E.; Vanzo, R.; Carbone, P.S. Initial Investigation of Comfort Levels, Motivations, and Attitudes of Volunteers During Therapeutic Recreation Programs. Therap. Rec. J. 2015, 49, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Wekesser, M.; Costa, G.H.; Pasik, P.J.; Erickson, K. “It Shaped My Future in Ways I Wasn’t Prepared for—In the Best Way Possible”: Alumni Volunteers’ Experiences in an Adapted Sports and Recreation Program. Adapt. Physical Activ. Q. 2023, 40, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, B.H. Promoting Global Citizenship and Multiculturalism in Higher Education: The Korea International Cooperation Agency’s Global Volunteering in the Asia Pacific Region. Cult. Educ. 2023, 35, 218–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmiarek, M.; Poczta, J.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Motivations of Sports Volunteers at the 2023 European Games in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Zhang, J.J.; Connaughton, D.P. Comparison of Volunteer Motivations in Different Youth Sport Organizations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2010, 10, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumnig, M.; Schnitzer, M.; Beck, T.N.; Mitmansgruber, H.; Jowsey, S.G.; Kopp, M.; Rumpold, G. Approach and Avoidance Motivations Predict Psychological Well-Being and Affectivity of Volunteers at the Innsbruck 2008 Winter Special Olympics. Voluntas 2015, 26, 801–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Soares, J. Gestão Do Voluntariado Num Evento de Desporto Adaptado: Motivação, Expetativas, Participação e Intenção de Repetir a Experiência. Rev. Int. Gest. Desp. 2020, 10, e10001. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Khoo, S. Predicting Future Volunteering Intentions Through a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Bahen, M.; Hanna, C.; Borisoff, J.; Mattie, J.; Mortenson, W.B. Setting the Sails: Stakeholders Perceptions of an Adapted Sailing Program. Leis. Sci. 2022, 44, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmiarek, M. Research Trends in Sports Volunteering: A Focus on Polish Contributions to Global Knowledge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G. Volunteering in Community Sports Organisations and Associations. In The Routledge Handbook of Volunteering in Events, Sport and Tourism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 144–157. ISBN 978-1-032-12724-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, T.J.; Terwiel, F.A.; Vetitnev, A.M. Evidence of a Social Legacy from Volunteering at the Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Event Manag. 2022, 26, 1707–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Sharpe, S.; Darcy, S. Where Are the Indigenous and First Nations People in Sport Event Volunteering? Can You Be What You Can’t See? Tour. Rec. Res. 2023, 48, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T.J.; Benson, A.M. London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Including Volunteers with Disabilities—A Podium Performance? Event Manag. 2014, 18, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, P.; Kim, A. Human Resource Management in Sport and Recreation, 4th ed.; Human Kinetics, Inc.: Champaign, IL, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-7182-1002-8. [Google Scholar]

- Haslett, D.; Smith, B. Disability, Sport and Social Activism. In Athlete Activism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 65–76. ISBN 978-1-003-14029-0. [Google Scholar]

- Al Harthy, S.S.; Hammad, M.A.; Awed, H.S. The Role of Sports Clubs in Promoting Social Integration among People with Disabilities in Saudi Arabia. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakakis, T.; Schoemaker, J.; Lera-Lopez, F.; De Boer, W.; Čingienė, V.; Papić, A.; Ahlert, G. Valuing the Contribution of Sport Volunteering to Subjective Wellbeing: Evidence from Eight European Countries. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1308065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarqui-Silva, L.E.; Sánchez-Salinas, M.V.; Garcés-Mosquera, J.E. El Deporte Adaptado, Inclusivo y Paralímpico: Una Ruptura de Estereotipos Discriminatorios Contra La Diversidad Funcional. Rev. Innova Educ. 2022, 5, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rico, G.; Tena-Medialdea, J.; Cañadas, M.; Pérez-Campos, C.; García-Grau, P. Inclusive Higher Education: A Guide to Designing a Support Plan on Disability and Inclusion in Universities; Brief Ediciones: Valencia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Descriptor | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Volunteerism | “Sport Volunteer” OR sport volunteer* OR “Sport volunteer*” OR Sport Voluntar* OR “Sport Voluntar*” OR sport volunteerism OR volunteering |

| Outcome | Motivation OR motives OR motiv* OR Satisfaction OR Commitment OR Engagement |

| Context | disabilit* OR disable* OR impair* OR handicap* OR “adapt* sport*” |

| Database | Search Protocol |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | “Sport Volunteer” OR sport volunteer* OR “Sport volunteer*” OR Sport Voluntar* OR “Sport Voluntar*” OR sport volunteerism OR volunteering (Topic) and Motivation OR motives OR motiv* OR Satisfaction OR Commitment OR Engagement (Topic) and disabilit* OR disable* OR impair* OR handicap* OR “adapt* sport*” (Topic) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Sport Volunteer” OR sport AND volunteer* OR “Sport volunteer*” OR sport AND voluntar* OR “Sport Voluntar*” OR sport AND volunteerism OR volunteering) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (motivation OR motives OR motiv* OR satisfaction OR commitment OR engagement) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (disabilit* OR disable* OR impair* OR handicap* OR “adapt* sport*”)) |

| PsycInfo | (“Sport Volunteer” OR sport volunteer* OR “Sport volunteer*” OR Sport Voluntar* OR “Sport Voluntar*” OR sport volunteerism OR volunteering) AND (Motivation OR motives OR motiv* OR Satisfaction OR Commitment OR Engagement) AND (disabilit* OR disable* OR impair* OR handicap* OR “adapt* sport*”) |

| SportDiscus | (“Sport Volunteer” OR sport volunteer* OR “Sport volunteer*” OR Sport Voluntar* OR “Sport Voluntar*” OR sport volunteerism OR volunteering) AND (Motivation OR motives OR motiv* OR Satisfaction OR Commitment OR Engagement) AND (disabilit* OR disable* OR impair* OR handicap* OR “adapt* sport*”) |

| Year | 2007 | 2010 | 2011 | 2014 | 2015 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2023 |

| N Studies | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Country | Number of Studies Published |

|---|---|

| Austria | 1 |

| China | 1 |

| England | 1 |

| Korea | 1 |

| Malaysia | 3 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| South Africa | 1 |

| Spain | 2 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| USA | 3 |

| Journal | Number of Studies Published |

|---|---|

| Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly | 2 |

| African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance | 2 |

| Anales de Psicología | 1 |

| Disability and Rehabilitation | 1 |

| European Sport Management Quarterly | 1 |

| Leisure Sciences | 1 |

| Materiales para la historia del deporte | 1 |

| PLoS ONE | 1 |

| Revista Intercontinental de Gestão Desportiva | 1 |

| Sport Management Review | 1 |

| Therapeutic Recreation Journal | 1 |

| Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development | 1 |

| Voluntas | 2 |

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of sample | ||

| Event volunteers | 6 | 37.50 |

| Organization volunteers | 6 | 37.50 |

| Students | 4 | 25.00 |

| Type of organization | ||

| Care organization | 1 | 6.25 |

| Disabled organization | 2 | 12.50 |

| International Sport Event | 3 | 18.75 |

| National and International Sport Event | 2 | 12.50 |

| National Sport Event | 3 | 18.75 |

| Sport and recreation organizations | 4 | 25.00 |

| University | 1 | 6.25 |

| Type of disability | ||

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | 1 | 6.25 |

| Different types of disabilities | 5 | 31.25 |

| Intellectual disabilities | 6 | 37.50 |

| Physical disabilities | 2 | 12.50 |

| Severe mental health disorders | 1 | 6.25 |

| Not reported | 1 | 6.25 |

| Variable | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| Motivation | 13 |

| Satisfaction | 4 |

| Future intentions | 3 |

| Participation facilitators; Participation barriers; Experiences | 2 |

| Benefits; Challenges; Comfort; Commitment; Competence; Drop-out; Perceptions; Personal outcomes; Physical conditions; Potential solutions; Program impact; Recognition; Responsibility with tasks; Rewards; Societal attitudes | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Llerena, A.; Angosto, S.; Pérez-Campos, C.; Alcaraz-Rodríguez, V. A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations. Disabilities 2025, 5, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020033

Muñoz-Llerena A, Angosto S, Pérez-Campos C, Alcaraz-Rodríguez V. A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations. Disabilities. 2025; 5(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Llerena, Antonio, Salvador Angosto, Carlos Pérez-Campos, and Virginia Alcaraz-Rodríguez. 2025. "A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations" Disabilities 5, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020033

APA StyleMuñoz-Llerena, A., Angosto, S., Pérez-Campos, C., & Alcaraz-Rodríguez, V. (2025). A Systematic Review of Volunteer Motivation and Satisfaction in Disability Sports Organizations. Disabilities, 5(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020033