The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Disability, Employment, and the Ideal Worker

Under the temporal practices of the 2005 welfare to work legislation, two new classes of disability emerged: those ‘partially mobile’ disabled subjects who signified momentary immobility through a current inability to work (but had the bodily temporal dispositions to actively work towards a state of improvement) and those ‘fixed’ disabled welfare subjects who remained permanently excluded from the improvement of the nation because of their ‘continuing inability to work’.[24] (p. 74)

The temporal relationship between disability social entitlements, state classification regimes and practices of social exclusion is likely to fluctuate with each temporal murmur or seismic shift.

The resultant temporal socio- classification process is underpinned by relations of exchange, and it is through this process that disabled people and their bodies become inscribed with value.

1.2. Employment Pathways for People with a Disability: ADEs, Supported and Open Employment

The biopsychosocial approach fundamentally reshapes the way ‘work capacity’ is understood and requires a wide range of employment supports to be offered to all people with disability to best address the barriers to work experienced by the individual.[21] (p. 7)

1.3. Work Integration Social Enterprises and Shared Resilience

2. Methodology

3. Findings

3.1. ‘Don’t Worry, Mate, Get on with Your Job’: Social Stigma, Employer Confidence, and Open Employment Funding Challenges

I don’t want to stay here the rest of my life. I want to go out there in employment and socialise and talk to people.(Patrice, November 2021)

In open employment I feel like I’d be on my own a little bit with a situation like that. Like, I could talk to my boss, but most bosses would say, “Don’t worry, mate, get on with your job”, or something like that. I think he would say, “It’s your own issue, deal with it in your own time”, or something like that.(Max, November 2021)

For any employer that wants to employ a person with a disability, they’ve got to be on board in regards to a cultural perspective. Absolutely has to be critical that they want to make a difference and be a positive influence on this person’s life and have empathy.(Jean, support worker, November 2021)

Success really does rely on the other staff and the culture of the organisation or company and that’s why sometimes those smaller companies are really good, because it might be an owner operator, which is less likely to sort of turn over [staff]. Or if it’s a bigger company—it really needs to be embedded into the culture.(Grace, training staff, October 2021)

I think the problem is when people with disability go out into open employment, I think they’re scared. Because when they go out there, people with disability, “oh, they can’t do this, and they can’t do that”. And they get really nervous. But once they’re here [supported work], they’ve got people to help them too. I’ve been watching, and since I’ve got my confidence up, and then when you go out in employment, they get all timid. I thought, “Oh, shivers, when I go in employment, where do I go?” I thought, “With a disability, what do I do?”.(Patrice, November 2021)

I thought I was selling the products but I was on cashier, which is not my strength, with money. And I was only working there for two weeks. They’d showed me one time how to use the till, but… I work by being shown things a couple of times. They walked in front of me and did it themselves, didn’t explain what they were doing or anything… they didn’t give me a chance, so I was only working there for two weeks…

I wasn’t really comfortable with that and I was always calling and asking, “How do I do this, how do I do that?”.(Kelly, December 2021)

I think… for us as a business… we have to acknowledge that our warehouse workers… are basic trained warehouse staff. They are not trained in dealing with any challenges [in employee behaviours].(Jacqui, employer, January 2022)

Time management. Dealing with difficult other employees or customers. Being punctual. Being consistent in the work they do. Good hygiene. Having a work/life balance and not relying on others to assist. Expectations. Obligations. Working to a deadline, or working to a budget.(Jean, support worker, October 2021)

…There is a lot of conversation about holistic supports and all of the extra things that they [NDIS] could be doing… but the way that [NDIS] are often modelled limits the amount of support they can provide each jobseeker. Our supported employees moving into open employment and their new employer often require intensive supports, and within the workplace, particularly at the start. This is often outside of the scope of what a DES [disability employment services] provider can assist with.(Grace, training provider, October 2021)

3.2. ‘It’s a Step-by-Step Process’: Shared Resilience, Support, and Customisation in Employment

3.2.1. The Role of Customisation in the Employer–Employee Relationship

I reached out to them, and before you know it, we’ve got a job painting… it’s just getting the conversation started, but where does it end? There is really no endpoint.(Grace, interviewed October 2021)

I think finding what they like to do and what interests them is key because if they’re interested in something, they will know it very well.(Mark, employer, November 2021)

I think it’s a step-by-step process of having someone understand where they want to go, how they might do it, and the confidence to be able to take those steps without being burnt along the way.(Anthony, education stakeholder, October 2021)

…in terms of when she got moved around, it really unsettled her. So, I think just to have that knowledge, if we tell our Warehouse lead, “Don’t move this person around”, she won’t get moved around.(Jacqui, employer, January 2022)

If you’ve got an employer that’s taking on one person and giving them a role within their organisation, they can actually be specific and very tailored around what that person needs. And so then, they just need to have the tools and the toolbox… and they’ve got to be willing to invest in that to set up the environment.(Dave, manager/trainer, October 2021)

They’ve got to understand around—there’s got to be some training around that individual. So, I guess the ability, if you’ve got an employer that’s taking on one person and giving them a role within their organisation, they can actually be specific and very tailored around what that person needs.(Dave, manager/trainer, October 2021)

…if we’re going into an employer, we don’t want to be ambiguous… So, if I was going to go into a factory, I would’ve already thought about what tasks would happen in this factory… you just be very specific about some ideas of things that our participants could do to generate those conversations in the beginning.(Lauren, employment support staff, December 2021)

We’ll do a trial day, whether it’s two hours, three hours, four hours, we’ll bring our supported employees to you. We’ll trial the work, which means our guys can feel it, touch it, see if it meets our scope of work.(Alan, trainer/manager, October 2021)

3.2.2. ‘You’re Not Looked at or Judged Here…’: Creating a Culture of Respect

Yes, we support them and everything, but we’re becoming more like an Open Employment style business because we’re getting more staff and they’re working side by side, rather than, “Let me train you and here’s a job and I’ll just supervise and watch”.(Chris, manager, November 2021)

…it does make it more enjoyable, and more of a happier workplace. But it also makes it an efficient workplace as well… So it actually—you know, being a team player it actually helps it be comfortable as a person, but it also makes it more efficient. You get the job done better, and you also get the job done safer. And the more safe you are, the smarter you work.

…there is even like there’s a couple of jobs that I can do that another job I can’t do as well, and then I can do that job for her and take over, and do that job for her. And then there’s another girl that’s—that I can’t do the job as well, and she takes over from me. And we all help each other wherever we can.

We’ve all got different strengths, and different needs, and what we can do and what we can’t do.(Mike, supported employee, October 2021)

4. Discussion

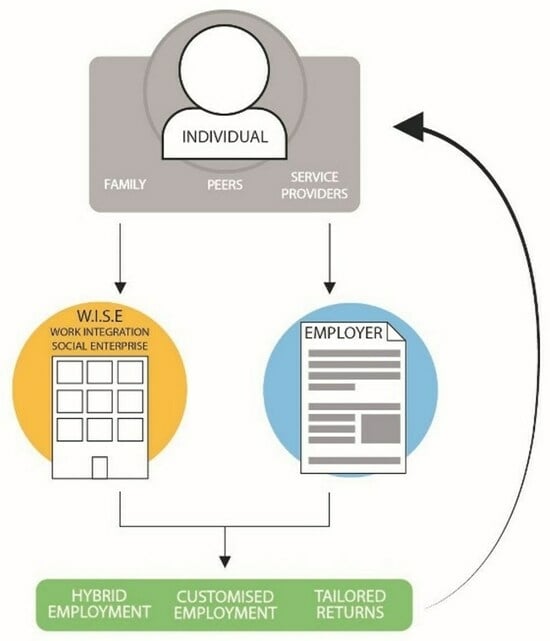

Tailored Returns and Hybrid Employment for People Living with a Disability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnes, C.; Mercer, G. Disability, work, and welfare: Challenging the social exclusion of disabled people. Work. Employ. Soc. 2005, 19, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bend, G.L.; Priola, V. There is nothing wrong with me: The materialisation of disability in sheltered employment. Work. Employ. Soc. 2021, 37, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mik-Meyer, N. Disability and ‘care’: Managers, employees and colleagues with impairments negotiating the social order of disability. Work. Employ. Soc. 2016, 30, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerud, K.L. Disability discrimination: Employer considerations of disabled jobseekers in light of the ideal worker. Work. Employ. Soc. 2022, 37, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.; Hennekam, S. When can a disability quota system empower disabled individuals in the workplace? The Case of France. Work. Employ. Soc. 2021, 35, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, O.; Dawson, E.; Lewis, A.; O’Halloran, D.; Smith, W. Working It out: Employment Services in Australia, Per Capita and the Australian Unemployed Workers’, 2018 Union, Melbourne. Available online: https://percapita.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Working-It-Out-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Meltzer, A.; Kayess, R.; Bates, S. Perspectives of people with intellectual disability about open, sheltered and social enterprise employment: Implications for expanding employment choice through social enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2018, 14, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A. (Ed.) The changing landscape of youth and young adulthood. In Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood, 2nd ed.; Furlong; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- King, H.; Crossley, S.; Smith, R. Responsibility, resilience and symbolic power. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 69, 920–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Campbell, P.; Howie, L.J. Rethinking Young People’s Marginalisation: Beyond Neoliberal Futures? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.P.; Owen, R.; Fisher, K.R.; Gould, R. Human rights and neoliberalism in Australian welfare to work policy: Experiences and perceptions of people with disabilities and disability stakeholders. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2014, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davister, C.; Defourny, J.; Gregoire, O. Work Integration Social Enterprises in the European Union: An Overview of Existing Models, EMES European Network. 2004. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/90492/1/Work%20Integration%20Social%20Enterprises%20in%20the%20European%20Union_An%20overview%20of%20existing%20models.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. 2019. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability and the Labour Force. 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/disability-and-labour-force (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. People with Disability in Australia. 2022. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia/contents/employment/unemployment (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Graduate Careers Australia. Employment and Salary Outcomes of Higher Education Graduates from 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.graduatecareers.com.au/files/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/gradstats-2017-3.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- OECD. Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers—A Synthesis of Findings Across OECD Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/publications/sickness-disability-and-work-breaking-the-barriers-9789264088856-en.htm (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- NDIS. What is the NDIS? 2022. Available online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/what-ndis (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Wilson, E.; Qian-Khoo, J.; Campain, R.; Joyce, A.; Kelly, J. Summary Report. In Mapping the Employment Support Interventions for People with Work Restrictions in Australia; Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, M.T. The portfolio ideal worker: Insecurity and inequality in the new economy. Qual. Sociol. 2020, 43, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Lecca, L.I.; Alessio, F.; Finstad, G.L.; Bondanini, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Arcangeli, G.; Mucci, N. COVID-19-Related mental health effects in the workplace: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatic, K. Disability and Neoliberal State Formations; Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, D.; Wass, V. Disability in the Labour Market: An Exploration of Concepts of the Ideal Worker and Organisational Fit that Disadvantage Employees with Impairments. Sociology 2013, 47, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, F.; Bäckström, M.; Wolgast, S. Company norms affect which traits are preferred in job candidates and may cause employment discrimination. J. Psychol. 2017, 146, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Moloney, M.; Ciciurkaite, G. People with Physical Disabilities, Work, and Well-Being: The Importance of Autonomous and Creative Work’, Factors in Studying Employment for Persons with Disability; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.; Qian-Khoo, J.; Crosbie, J.; Campbell, P. Paper 1: Understanding the Employment Ecosystem for People with Intellectual Disability; Explaining the Evidence for Reform Series; Centre for Social Impact: Hawthorn, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barraket, J.; Campbell, P.; Moussa, B.; Suchowerska, R.; Farmer, J.; Carey, G.; Joyce, A.; Mason, C.; McNeill, J. Improving Health Equity for Young People? The Role of Social Enterprise: Final Report; Centre for Social Impact Swinburne: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; De Cotta, T.; Kilpatrick, S.; Barraket, J.; Roy, M.; Munoz, S.-A. How work integration social enterprises help to realise capability: A comparison of three Australian settings. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 12, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.; Robinson, S.; Fisher, K.R. Barriers to finding and maintaining open employment for people with intellectual disability in Australia. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; McVilly, K.R.; McGillivray, J.; Chan, J. Developing Open Employment Outcomes for People with an Intellectual Disability Utilising a Social Enterprise Framework. J. Vocat. Rehabilitation 2018, 48, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Defining social enterprise. In Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Polices and Civil Society; Nyssens, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Disability Services Act. Disability Services Act 1986 No. 129, 1986, Prepared by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, Canberra. 1986. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/3171/128677/F-1889037640/AUS3171%202017.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Wilson, E.; Qian-Khoo, J.; Cutroni, L.; Campbell, P.; Crosbie, J.; Kelly, J. The ADE Snapshot, Explaining the Evidence for Reform Series; Centre for Social Impact: Hawthorn, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.R.; Keeton, B. Job Development Fidelity Scale, Griffin-Hammis Associates. 2019. Available online: https://dmh.mo.gov/sites/dmh/files/media/pdf/2019/08/customized-employment-webinar-5-resource-06222018.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Campbell, P.; Howie, L.; Moussa, B.; Mason, C.; Joyce, A. Youth resilience programs in Australia and the US: Beyond neoliberal social therapeutics? J. Youth Stud. 2021, 26, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, W. Socio-political Perspectives on Action Research. Traditions in Western Europe. Int. J. Action Res. 2011, 7, 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, D.; More, E.; Steane, P. Action learning intervention as a change management strategy in the disability services sector—A case study. ALAR Action Learn. Action Res. J. 2013, 18, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ollerton, J. IPAR, an inclusive disability research methodology with accessible analytical tools. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2012, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.; Easterbrook, E.; Bendetson, S.; Lieberman, S. TransCen, Inc.’s WorkLink program: A new day for day services. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2013, 40, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Disability Employment Research and Practice (CDERP). Customised Employment Work First Customised Employment™ Program Outline. 2018. Available online: https://www.cderp.com.au/ewExternalFiles/CE%20Program%20Outline.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Harvey, J.; Szoca, P.; Rosaa, M.D.; Pohlb, M.; Jenkinsa, J. Understanding the competencies needed to customize jobs: A competency model for customized employment. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2013, 38, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, W. Customised Employment. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/610886 (accessed on 7 September 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campbell, P.; Wilson, E.; Howie, L.J.; Joyce, A.; Crosbie, J.; Eversole, R. The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability. Disabilities 2024, 4, 111-126. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010008

Campbell P, Wilson E, Howie LJ, Joyce A, Crosbie J, Eversole R. The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability. Disabilities. 2024; 4(1):111-126. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampbell, Perri, Erin Wilson, Luke John Howie, Andrew Joyce, Jenny Crosbie, and Robyn Eversole. 2024. "The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability" Disabilities 4, no. 1: 111-126. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010008

APA StyleCampbell, P., Wilson, E., Howie, L. J., Joyce, A., Crosbie, J., & Eversole, R. (2024). The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability. Disabilities, 4(1), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4010008