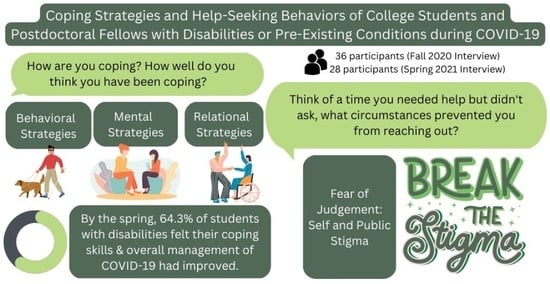

Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

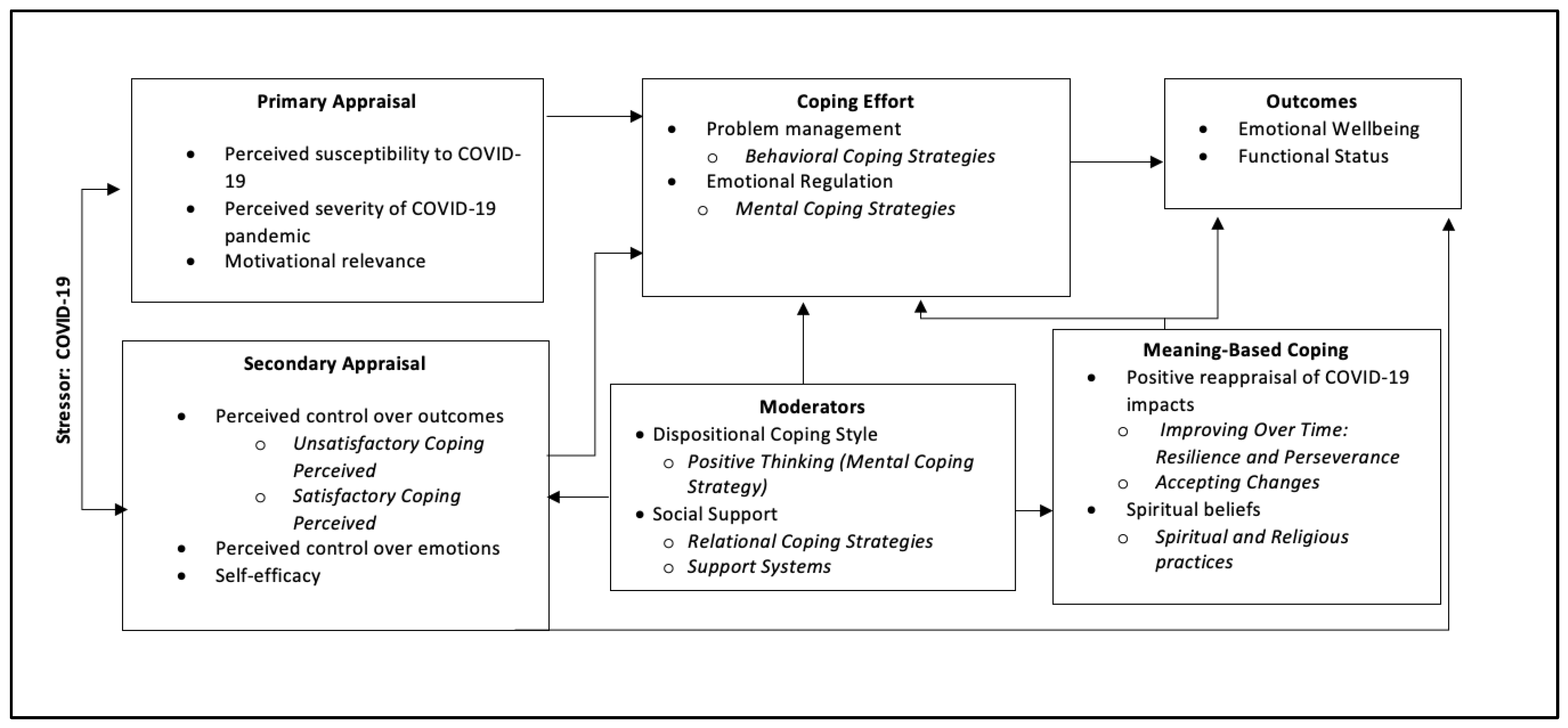

Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Interview Procedures

2.4. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Theme 1: “Behavioral Coping Strategies”

“More than anything, just to keep a good headspace I exercise, and I also have an ESA, that’s definitely very helpful when it comes to coping, but mostly exercise and then the rest of the time is spent studying.”

“Music really helped a lot lately (…) produces a very relaxing effect. So that has been more helpful than I was anticipating (…) I have also joined a discord or chat board for one of the video game streamers that I like to watch and it’s been a good place to decompress.”

“The medication is not as helpful, (…) I feel like a walk it’s more appropriate for me because I’m able to enjoy nature and enjoy the weather outside. Enjoy just another environment other than this apartment, so I feel like that’s the best thing.”

“Making a schedule was really helping me, especially at times when we were having exams close by, and my schedule becomes really packed with things that have to get done. When I have a schedule made, a planned routine, it really helps me decrease my levels of stress.”

“Staying off news and social media, that’s really helped. Over the last year, not paying attention to the news is great, but you want to look to where to find stuff more positive (…) so there there’s a lot of things I’ve learned, how to almost change or adapt to what I needed for my mental health”.

3.2.2. Theme 2: “Mental Coping Strategies”

“I like to stay busy. That helps with a lot of my anxiety and depression. If I’m staying busy, then I feel like I’m doing something and I feel I have a purpose almost as silly as that sounds, not thinking about it really.”

“I’ve been trying to stay busy with school. (…) If I think about it too much I’ll get sad about it. I found ways of doing things to take my mind away from it.”

“I took a course on critical thinking and that taught me mindfulness and self-reflection. So I was trying to put time towards myself to self-reflect, understand my feelings, try to understand why I’m feeling like this, and to try to find ways to cope with it. Sitting down with myself and self-reflecting was really helping me to kind of manage this level of stress that I was under.”

“You have to count the victories whatever they are no matter how you got to that point, you’re still alive. You’re still thriving in some shape form or fashion you haven’t dropped out of school. You haven’t quit your job. You pay your bills most of the time, so I would say I’m doing pretty great in that. I like to try to be optimist about things.”

“I think with time it was more about accepting that this is here to stay for a while, so to not feel bad all the time for things not being perfect, having a positive outlook has helped.”

“Watching church online is helpful and I have several friends from a Bible study that we all encourage each other.”

“It’s a form of escapism, a lot of the things I watch or do are a form of that. I’m just trying to go to another place and it’s also not helping me because I’m just avoiding the issue entirely and there’s not much I can do about it. So I still avoid it.”

3.2.3. Theme 3: “Relational Coping Strategies: Remaining Connected with Others”

“I’ve been trying to be really conscious of that and make time to see people and socialize, because that is really important to me and knowing that finding your people that you can talk to about life and stressors and having those people in your life that you can lean on a little bit with everything being really difficult right now, I feel like it’s really important.”

3.2.4. Theme 4: “Satisfactory Coping Perceived”

“I’m proud of myself for booking an appointment with my nutritionist and … I feel like that’s a positive step in like this stress eating part, we like worked out like an eating plan. Maybe I can start eating a little bit better. I’m taking control in that aspect.”

“At times you get these thoughts but I just would say it’s a phase and it’s going to go away and we need to just accept it because in life there will be many challenges and with each challenge or each phase we tend to get better.”

“I’m trying to take life as it comes COVID-19 changed a lot but life is what it is, and through journaling, trying to remind myself, I would write about it. I should really live and let go, things will happen as they happen, and so that’s really made me more mindful and also lessened Imposter Syndrome.”

“Going outside and walking and being outdoors, especially with the warm weather kind of helps me not feel as trapped and isolated, so that’s been really nice getting out and seeing other people too has benefits from a distance.”

3.2.5. Theme 5: “Unsatisfactory Coping Perceived”

“I am not coping very well when it comes to the personal side of things and I’m working with my therapist to deal with that part because I’m still not coping very well. I don’t know what to do to cope.”

“I tend to be very harsh on myself. I try to hold myself to a really high standard and just feel like I haven’t been able to maintain the level of organization and productivity that I usually do during this time. Just because it has put so much stress, which has been very detrimental to my mental health.”

“Stress eating—It got really bad. I’d buy a family sized bag of chips and I just eat it in one sitting and you feel terrible after you eat that. There’s some other coping things, I’d go on Tik Tok for 5 hours at a time, so you feel guilty after that too. I don’t think I’m coping healthy at all.”

“I feel I’m not as productive and that makes me feel really inadequate sometimes … because if I sit here on my phone for like 3 hours and I feel really guilty about that and it makes me feel not good about myself. Also, I don’t have the motivation to actually do work, so it’s this really bad balance.”

“I have ADHD and I’m on medication for it, so I’ve kind of struggled with productivity at times, but this has been a new lesson in that struggle. It is impossible to dissociate my feelings of self-worth from my productivity.”

3.2.6. Theme 6: “Improving over Time: Resilience and Perseverance”

“I kind of became a different person as the year went on and I think everyone has. I don’t think anyone is the same person that they were when this whole thing started out, but as I grew and evolved and I learned more things, my coping strategies also kind of morphed along with it.”

“Now, I’m very much in better place in managing my mental health (…) think it has mostly to do with the looking at resources that are available. Overall, changing the lifestyle to have more of a routine that is not just work but also taking some time off from time to time.”

“I had the time to sort of focus on my mental health, which in the past kind of kept getting pushed aside because I was busy with work and school so it gave me the time to sort of reconnect with people in my life and start therapy, start medication for anxiety, I think in the beginning my mental health sort of deteriorated but as time has gone by, I think I’ve gotten better actually.”

3.2.7. Theme 7: “Support Systems”

3.2.8. Theme 8: “Perceived Support Seeking Barriers”

“Sometimes I do get kind of sad and in a funk and I won’t reach out to anyone because I feel like I’m a burden or they don’t want to talk about that and it’s just too pessimistic to talk about.”

“I can’t move when I want to. I can’t do the things I want to and I really bottled it up inside and it’s because being in a caring profession, the weight of putting so much on people, so sometimes I internalize a lot of things just so I won’t be a burden but it just got too much to handle really. It was just too emotional for me.”

“Sometimes I’m not in a frame of mind to talk to people about it, I don’t have the energy to explain to people what’s going on. With friends, everyone is going through something so the person you’re reaching out to might not also be in good frame of mind and you can’t just like unload your problems on that person. I think all the COVID-19 related breakdowns and anxiety played out like in those ways.”

“I don’t want to let anybody down (…) I don’t like to say I’m having a problem. I’m a whole person. I don’t want to be defined by my disease, but that can be a problem and so I don’t like to say I took on too much and that’s why I’m not getting anything done and I’m exhausted and I feel like I failed.”

“It’s one of the things I constantly battle with. I’m having a lot of physical health issues but also if you have anxiety is it’s very physically exhausting at times because you’re constantly worried, especially to the point It’s just debilitating, that gets me behind sometimes on work. I just can’t give the energy. Then also having physical ailments ----I never want anybody to label me as a person like ‘oh she’s got so much stuff going on, she can’t finish her work, she isn’t meant to be in this program to do this’. I don’t want to get labelled like someone lowered their expectations on me. It’s been frustrating for myself because I want to give more, but I just really can’t.”

3.3. Unique Patterns across Racial Identity Groups and Grade Classification

4. Discussion

Use of the TMSC Framework to Interpret Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gin, L.E.; Guerrero, F.A.; Brownell, S.E.; Cooper, K.M. COVID-19 and Undergraduates with Disabilities: Challenges Resulting from the Rapid Transition to Online Course Delivery for Students with Disabilities in Undergraduate STEM at Large-Enrollment Institutions. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, ar36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, C.A.; Ewing, L.; Heath, N.L.; Goldstein, A.L. When social isolation is nothing new: A longitudinal study on psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2021, 62, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Nurius, P.; Sefidgar, Y.; Morris, M.; Balasubramanian, S.; Brown, J.; Dey, A.K.; Kuehn, K.; Riskin, E.; Xu, X. How Does COVID-19 impact Students with Disabilities/Health Concerns? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.05438. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, M.; Hickey, K. Needs a little TLC: Examining college students’ emergency remote teaching and learning experiences during COVID-19. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, A.; Upshaw, K.; Estep, C.; Lanzi, R.G. Getting to the Sandbar: Understanding the Emotional Phases of COVID-19 among College and University Students. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 2956–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligus, K.; Fritzson, E.; Hennessy, E.A.; Acabchuk, R.L.; Bellizzi, K. Disruptions in the management and care of university students with preexisting mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Leigh, J. Ableism in Academia: Theorising Experiences of Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses in Higher Education; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchen Lipson, S.; Gaddis, S.M.; Heinze, J.; Beck, K.; Eisenberg, D. Variations in student mental health and treatment utilization across US colleges and universities. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, K.S.; Proctor, B.E. Adaptation to college for students with and without disabilities: Group differences and predictors. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2010, 22, 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten, R.A., Jr.; Bernardi, L.; Härkönen, J.; Antonucci, T.C.; Dykstra, P.A.; Heckhausen, J.; Kuh, D.; Mayer, K.U.; Moen, P.; Mortimer, J.T. Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 45, 100360. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, E.; Fortune, N.; Llewellyn, G.; Stancliffe, R. Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, A.; Murchake, H.; Chalk, H.M. Positive Disability Identity Predicts Sense of Belonging in Emerging Adults with a Disability. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2018, 23, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Daly-Cano, M.; Newman, B.M. A sense of belonging among college students with disabilities: An emergent theoretical model. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2015, 56, 670–686. [Google Scholar]

- Recksiedler, C.; Landberg, M. Emerging Adults’ Self-Efficacy as a Resource for Coping With the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forber-Pratt, A.J.; Lyew, D.A.; Mueller, C.; Samples, L.B. Disability identity development: A systematic review of the literature. Rehabil. Psychol. 2017, 62, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.S.; Willhelm, A.R.; Koller, S.H.; de Almeida, R.M.M. Risk and protective factors for suicide attempt in emerging adulthood. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2018, 23, 3767–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchetti, M.; Lee, J.H.; Aschwanden, D.; Sesker, A.; Strickhouser, J.E.; Terracciano, A.; Sutin, A.R. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sundarasen, S.; Chinna, K.; Kamaludin, K.; Nurunnabi, M.; Baloch, G.M.; Khoshaim, H.B.; Hossain, S.F.A.; Sukayt, A. Psychological impact of COVID-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: Toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. J. Personal. 2006, 74, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 647. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington, E.; Glanz, K.; Schwartz, M.D. Stress, coping, and health behavior. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 12, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J.; Tanner, J.L. Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, J. Life Adversity, Social Support, Resilience, and College Student Mental Health. Master’s Thesis, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Ackerman, R.A.; Depp, C.A.; Harvey, P.D.; Moore, R.C. A longitudinal investigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals with pre-existing severe mental illnesses. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Practicing phenomenological writing. Phenomenol. Pedagog. 1984, 2, 36–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. But is it phenomenology? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. A Pract. Guide Res. Methods 2015, 222, 248. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 2, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L.; Markey, K.; O’Donnell, C.; Moloney, M.; Doody, O. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre-existent mental health conditions: A scoping review. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 35, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baenas, I.; Caravaca-Sanz, E.; Granero, R.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Testa, G.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Treasure, J.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. COVID-19 and eating disorders during confinement: Analysis of factors associated with resilience and aggravation of symptoms. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Best, K.M.; Garmezy, N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Dev. Psychopathol. 1990, 2, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.T. Increasing resilience: Strategies for reducing dropout rates for college students with psychiatric disabilities. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2010, 13, 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L.; Mazefsky, C.A.; Eack, S.M. The combined impact of social support and perceived stress on quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder and without intellectual disability. Autism 2018, 22, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, A.M.; Molton, I.R.; Alschuler, K.N.; Ehde, D.M.; Jensen, M.P. Resilience predicts functional outcomes in people aging with disability: A longitudinal investigation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.M. Stigma and student mental health in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2010, 29, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucksted, A.; Drapalski, A.L. Self-stigma regarding mental illness: Definition, impact, and relationship to societal stigma. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2015, 38, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; River, L.P.; Lundin, R.K.; Wasowski, K.U.; Campion, J.; Mathisen, J.; Goldstein, H.; Bergman, M.; Gagnon, C.; Kubiak, M.A. Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Denenny, D.; Thompson, E.; Pitts, S.C.; Dixon, L.B.; Schiffman, J. Subthreshold psychotic symptom distress, self-stigma, and peer social support among college students with mental health concerns. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2015, 38, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, J.; Major, B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychol. Rev. 1989, 96, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Embarrassment and social organization. Am. J. Sociol. 1956, 62, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, J.D.; Boyd, J.E. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Roe, D.; Yanos, P.T. Toward understanding the insight paradox: Internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2007, 33, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, S.M.; Ramirez, D.; Hernandez, E.L. Contextualizing public stigma: Endorsed mental health treatment stigma on college and university campuses. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 197, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, E.; Strnadová, I.; Danker, J.; Walmsley, J.; Loblinzk, J. The impact of self-advocacy organizations on the subjective well-being of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, T.M.; Anderman, L.H.; Jensen, J.M. Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 75, 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.M.; Kutscher, E.L. College students with disabilities: Factors influencing growth in academic ability and confidence. Res. High. Educ. 2021, 62, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.B. Education in a Pandemic: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 on America’s Students; USA Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Lopez, K.A.; Willis, D.G. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McLean, K.C.; Koepf, I.M.; Lilgendahl, J.P. Identity Development and Major Choice Among Underrepresented Students Interested in STEM Majors: A Longitudinal Qualitative Analysis. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 10, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourea, L.; Christodoulidou, P.; Fella, A. Voices of Undergraduate Students With Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Psychol. Open 2021, 80, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Luo, S.; Mu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, X.; Xu, B.; Ding, Y.; Ling, P.; Zhou, M. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Pozo, C.; Harris, S.D.; Noriega, V.; Scheier, M.F.; Robinson, D.S.; Ketcham, A.S.; Moffat, F.L., Jr.; Clark, K.C. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. In Cancer Patients and Their Families: Readings on Disease Course, Coping, and Psychological Interventions; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, S.; Southgate, E.; Scevak, J.; Buchanan, R. University student perspectives on institutional non-disclosure of disability and learning challenges: Reasons for staying invisible. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 639–655. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Ebanks, V.; Jarman, M. Undergraduate students with nonapparent disabilities identify factors that contribute to disclosure decisions. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2018, 65, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitches, E.; Woodcock, S.; Ehrich, J. Shedding light on students with support needs: Comparisons of stress, self-efficacy, and disclosure. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2021. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

| Baseline Characteristic | Students with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions N = 36 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Disability Classification | ||

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) | 7 | 19.44 |

| Mobility/Sensory Impairment or Medical Disability | 6 | 16.67 |

| Psychiatric Disorder | 26 | 72.22 |

| Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) | 1 | 2.78 |

| University Designation | ||

| Graduate | 17 | 47.22 |

| Postdoctoral Fellow | 5 | 13.89 |

| Undergraduate | 14 | 38.89 |

| Gender | ||

| Cisgender Female | 27 | 75.00 |

| Cisgender Male | 6 | 16.67 |

| Gender-Nonconforming | 1 | 2.78 |

| Non-Binary | 1 | 2.78 |

| Other | 1 | 2.78 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 19 | 5 | 13.89 |

| 19–20 | 5 | 13.89 |

| 21–25 | 12 | 33.34 |

| 26–30 | 6 | 16.68 |

| 31–35 | 5 | 13.89 |

| Over 35 | 4 | 11.12 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 | 8.33 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 33 | 91.67 |

| Racial Identity | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 | 0.00 |

| Asian | 2 | 5.56 |

| Black or African American | 8 | 22.22 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other Race | 2 | 5.56 |

| Two or more races | 4 | 11.11 |

| African American and Filipino | 1 | 2.78 |

| American Indian and White | 1 | 2.78 |

| Asian and White | 2 | 5.56 |

| White | 20 | 55.56 |

| US Citizenship | ||

| US Citizen | 30 | 83.33 |

| Non-US Citizen | 6 | 16.67 |

| Permanent resident | 2 | 5.56 |

| International | 3 | 8.33 |

| Non-US National | 1 | 2.78 |

| School | ||

| Arts and Sciences | 14 | 38.89 |

| Business | 2 | 5.56 |

| Dentistry, Medicine, Optometry | 4 | 11.11 |

| Education | 1 | 2.78 |

| Engineering | 2 | 5.56 |

| Graduate | 4 | 11.11 |

| Health Professions | 1 | 2.78 |

| Joint Health Sciences | 4 | 11.11 |

| Nursing | 1 | 2.78 |

| Public Health | 3 | 8.33 |

| Projected Graduation Year | ||

| 2020 | 3 | 8.33 |

| 2021 | 9 | 25.00 |

| 2022 | 9 | 25.00 |

| 2023 | 4 | 11.11 |

| 2024 | 9 | 25.71 |

| 2025 | 1 | 2.78 |

| 2026 or later | 1 | 2.78 |

| Disability or Condition(s) | Students with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions N = 36 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| ADHD | 3 | 8.33 |

| ADHD and Anxiety | 1 | 2.78 |

| Anxiety | 4 | 11.11 |

| Anxiety and Depression | 9 | 25.00 |

| Anxiety, Depression, and Bipolar | 1 | 2.78 |

| Asthma | 4 | 11.11 |

| Depression | 6 | 16.67 |

| Depression and ADHD | 2 | 5.56 |

| Depression and Bipolar | 1 | 2.78 |

| Depression, Eating Disorder, and ADHD | 1 | 2.78 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 2.78 |

| Muscular sclerosis (MS) and Asthma | 1 | 2.78 |

| OCD | 1 | 2.78 |

| TBI | 1 | 2.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolfner, C.; Ott, C.; Upshaw, K.; Stowe, A.; Schwiebert, L.; Lanzi, R.G. Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19. Disabilities 2023, 3, 62-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3010006

Wolfner C, Ott C, Upshaw K, Stowe A, Schwiebert L, Lanzi RG. Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19. Disabilities. 2023; 3(1):62-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolfner, Caro, Corilyn Ott, Kalani Upshaw, Angela Stowe, Lisa Schwiebert, and Robin Gaines Lanzi. 2023. "Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19" Disabilities 3, no. 1: 62-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3010006

APA StyleWolfner, C., Ott, C., Upshaw, K., Stowe, A., Schwiebert, L., & Lanzi, R. G. (2023). Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19. Disabilities, 3(1), 62-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3010006