Hearing Their Voices: Self Advocacy Strategies for People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

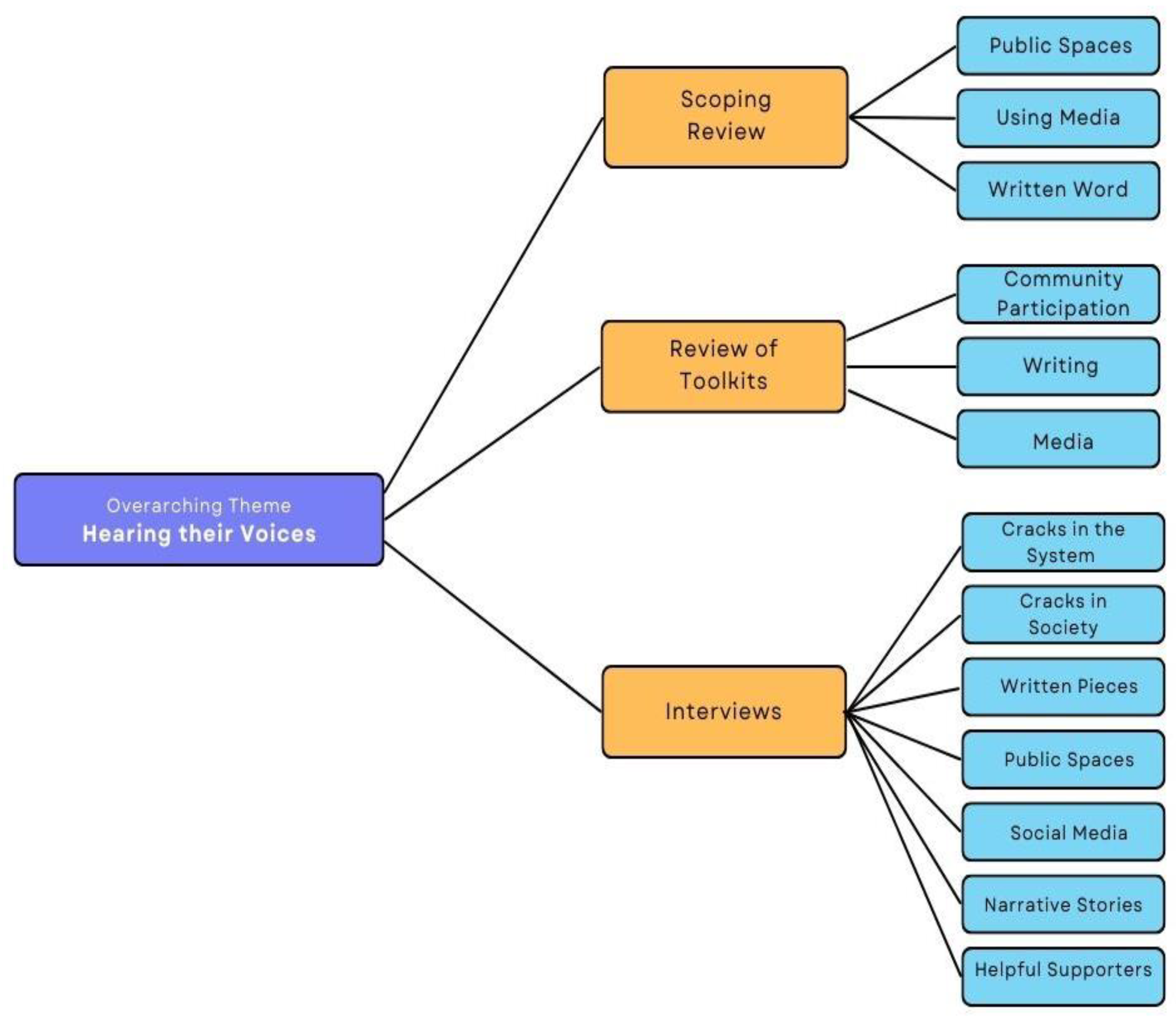

2. Methodology

- (a)

- A scoping literature review to identify local and international strategies for the self advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities;

- (b)

- A grey literature review of existing South African and international NGOs- and disabled people’s organisations (DPOs) based toolkits on strategies for people with intellectual disabilities to self advocate;

- (c)

- Semi-structured interviews to explore the perspectives of professionals at NGOs and DPOs internationally and locally, and of people with intellectual disabilities on their experience of self-advocacy.

2.1. The Scoping Review

2.2. Review of Existing Toolkits

2.3. Interviews

- (a)

- The owners and writers of self advocacy toolkits and manuals at organisations identified during the toolkit review were contacted via email to ascertain their interest in and to obtain informed consent for their participation in interviews.

- (b)

- The researcher identified Facebook groups which were set up for Self-Advocates with Intellectual Disability and their supporters. The nature and aim of the study was posted and interested community members invited to contact the researcher for more information. This process led to recruitment of 9 key informants with and without intellectualdisabilities.

3. Results

“you know, it starts off with the understanding that people with intellectual disabilities have a voice…. why would we exclude people with intellectual disabilities from the conversation?”—Richard

You know, this time in the world, there are people who don’t regard people with disabilities as advocates or don’t seem as an advocate to them. So, they can actually tell them, no, I am a person and I can, I can talk for myself. No one can make decisions for me, I can make my own decisions—Izzy

“I’ve said this before on various occasions we’ve reached transformation but we haven’t reached integration so transformation means we’ve got the legislation that says certain things with regards to discrimination, specifically discrimination in the workplace and those sort of things which is which is what we deal with (at the NGO) but we haven’t been able to reach integration’s as yet so we still struggling with the part where we go we have this legislation which is the transformative part of it but we haven’t integrated that into our mainstream society”—Richard

Ben: It’s views that are given by other people, that make people think like that… that intellectual disability is not right and stuff like that, (later)… You are baby. You are a baby… you act like a baby and stuff like that.

“In our country we are constantly making excuses about the high unemployment and how people with disabilities are at the bottom of the food chain”—Zola

“Now for me, when it was when I actually had to do a presentation or speech or talk for myself, then I at first, my first time I was nervous. Because I’m standing in front of, how can I say, 100 people then I have to give my life story. However, then later on again I got used to it because yeah, because it’s people that I know will be in the audience and they now want to talk to me”—Izzy

“And you know he would just love having the job of going out and I think there was something more than being located in a public space which was really important. And for some and for him to just, even you know, maybe I misinterpret, but I think for him just even just seeing the visibility of being in the public space and sometimes I would purposely not get enough milk, so he could just enjoy that experience of walking through a public cafe and feeling a sense of purpose in a regular public space.”—Meredith

Mom: we started getting phone calls from people all over wanting to interview him, and wanting to know about him and it was just truly an overnight sensation, I guess.

Interviewer: An overnight celebrity.

Mom: Yes, 15 s of fame.

George: Yes, that’s right… fame!

We need to work on the treatment of people with disabilities. Like the president said so… yes we do and maybe as you say to tell those stories so that we can highlight the injustice and the oppression injustice ja… and prejudice. With the stereotypes and stuff like that.

Interviewer: Okay, and the other people who are part of the advocacy group, who are they?

Derek: They are also, a few of them is our staff members. Like the job coaches are staff members and some of them is the trainees from each workshop and the job coach leads the meeting and we have one of our general managers to sit in the meeting also.

Interviewer: And tell me, tell me a little bit about the, the, idea of the supporters. Who was your supporter? What did they do for you?

Izzy: Now, you see, I actually paid the supporter. Now, yes, so the supporter that would now help me with getting my reports ready, that time she was the general manager.

Interviewer: Okay…

Izzy: Oh yeah, so whatever she did was she, compiled my reports with me, but in a professional way on her laptop. Yeah, and then she will now sit with me and ask me, now what do I want to say? And then, (name) was my other supporter, she was actually technically in the board meeting, so she was my supporter and she was my chauffeur.

Lexi: “but if we just take the powerful tool of our ears and our voices and listen maybe we could combine those stories and make a difference”

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maulik, P.K.; Mascarenhas, M.N.; Mathers, C.D.; Dua, T.; Saxena, S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnams, C.M. Perspectives of intellectual disability in South Africa: Epidemiology, policy, services for children and adults. Cur. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulla, V.; Zikhali, P. Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa 2019. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=3180 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Parliament of the Republic of South Africa. Constitution of South Africa. Chapter 2—The Bill of Rights, Act No. 108 of 1996; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 1996.

- Parliament of the Republic of South Africa. White Paper on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201603/39792gon230.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol, New York: United Nations General Assembly Congress. 2006. Available online: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Makgoba, M.W. The Life Esidimeni Disaster: The Makgoba Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/the-life-esidimeni-disaster-the-makgoba-report (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Makgoba, M.W. The report into the ‘circumstances surrounding the deaths of mentally ill patients: Gauteng province’. Available online: https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/Esidimeni%20full%20report.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Kleintjes, S.; McKenzie, J.; Abrahams, T.; Adnams, C. Improving the health of children and adults with intellectual disability in South Africa: Legislative, policy and service development. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2020, 2020, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Forum for Intelletual Disability. 2021. Available online: https://wcfid.co.za/5131-2/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Curryer, B.; Stancliffe, R.; Dew, A. Self-determination: Adults with intellectual disability and their family. J. Intellect. Dev. Disability. 2015, 40, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A. Essential Skills in Self-Advocacy; BC Epilepsy Society, BC Centre for Ability: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, E.; Strnadová, I.; Danker, J.; Walmsley, J.; Loblinzk, J. The Impact of Self Advocacy organizations on the subjective well being of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, J.; Bigby, C. Debates about dedifferentiation: Twenty-first century thinking about people with intellectual disabilities as distinct members of the disability group. Res. Pract. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 4, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Bigby, C. Self-Advocacy as a Means to Positive Identities for People with Intellectual Disability: ‘We Just Help Them, Be Them Really’. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redley, M.; Weinberg, D. Learning disability and the limits of liberal citizenship: Interactional impediments to political empowerment. Sociol. Health Illn. 2007, 29, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, K.; Stapleton, J.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Test, D.; Fowler, C.; Wood, W.M.; Brewer, D.M.; Eddy, S. A Conceptual Framework of Self-Advocacy for Students with Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2005, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.ti; Version 9.1 [ATLAS.ti 22 Mac]; Scientific Software Development GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://atlasti.com (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Petri, G.; Beadle-Brown, J.; Bradshaw, J. Redefining Self-Advocacy: A Practice Theory-Based Approach. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 17, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, P.; Bigby, C. Reflections on being a first generation self-advocate: Belonging, social connections, and doing things that matter. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARTAC. Self advocacy start up toolkit. Available online: https://selfadvocacyinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Self-Advocacy-Start-up-Toolkit-more-power-more-control-over-our-lives-2018.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Advocacy focus. The essential self advocacy toolkit. Available online: https://advocacyfocus.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/The_Essential_Self_Advocacy_Toolkit_1119.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Iriarte, E.; O’Brien, P.; McConkey, R.; Wolfe, M.; O’Doherty, S. Identifying the Key Concerns of Irish Persons with Intellectual Disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 27, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frawley, P.; Bigby, C. Inclusion in political and public life: The experiences of people with intellectual disability on government disability advisory bodies in Australia. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 36, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenwelge, C.; Zhang, D. The Effects of the Texas Youth Leadership Forum Summer Training on the Self-Advocacy Abilities of High School Students with Disabilities. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2012, 24, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raley, S.; Burke, K.; Hagiwara, M.; Shogren, K.; Wehmeyer, M.; Kurth, J. The Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction and Students with Extensive Support Needs in Inclusive Settings. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 58, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.K.; Faieta, J.; Tanner, K. Scoping Review of Self-Advocacy Education Interventions to Improve Care. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2020, 40, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, E. Management, leadership, and user control in self-advocacy: An english case study. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 51, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Pseudonym | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meredith & Mark | Meredith and Mark are community health workers in an organisation in Europe internationally. They have founded a self-advocacy programme and have extensive experience of self advocacy work with people with intellectual disabilities. They had recently developed and piloted a self-advocacy toolkit to support their work at the time of the Interview and were eager to train people to run the programme internationally. They were contacted via email and replied that they were interested in being interviewed. |

| 2 | Lexi | Lexi is a self advocate with cerebral palsy and an intellectual disability who replied to the Facebook advert. She was eager to be a part of this project and have her voice and opinion heard as a disability service user. She has experience as a radio show host and self-advocating in the public sector in America. |

| 3 | Zola | Zola is a community health worker and therapist at a local South African non-governmental organisation. She has experience working with people with intellectual disabilities and experience working with self-advocacy groups for people with intellectual and psychosocial disability. |

| 4 | Ben | Ben is a young man with an intellectual disability who is living and working in the community in South Africa. He has recently completed a learnership programme which included self-advocacy training. He opted to participate to discuss his self-advocacy efforts during a recent hospital admission and his experience at his local police station. |

| 5 | Richard | Richard is a manager of a South African NGO which offers training programmes and learnerships for people with intellectual disabilities. These programmes are registered with the local education department, so this ensures that learners obtain a qualification. As part of their curriculum, the organisation tackle issues of advocacy and self-advocacy. Richard has co-facilitated advocacy events for people with intellectual disability. |

| 6 | Alex | Alex is a young man with an intellectual disability who is living and working in South Africa. He has recently completed a learnership programme which included self-advocacy training. He opted to participate to discuss his self-advocacy efforts and his experiences as a person with a disability in his community context. |

| 7 | Ellis & George | George is a young man with Down’s Syndrome, and an intellectual disability from America who has become an international self-advocate on social media. He has become an internet sensation and posts regularly. His mother, Ellis, was present as a supporter during the session. |

| 8 | Derek | Derek was reached through snowball sampling, as a person that one of the other participants had worked with previously. He has an intellectual disability and is currently working at a local organisation in South Africa and acts as the self-advocacy representative for his organisation. |

| 9 | Izzy | Izzy was also reached through snowball sampling, as a person with whom one of the other participants had worked. She has an intellectual disability and is currently working at a local organisation in South Africa. She is an active self advocate. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldberg, C.; Kleintjes, S. Hearing Their Voices: Self Advocacy Strategies for People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa. Disabilities 2022, 2, 588-599. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2040042

Goldberg C, Kleintjes S. Hearing Their Voices: Self Advocacy Strategies for People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa. Disabilities. 2022; 2(4):588-599. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldberg, Cole, and Sharon Kleintjes. 2022. "Hearing Their Voices: Self Advocacy Strategies for People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa" Disabilities 2, no. 4: 588-599. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2040042

APA StyleGoldberg, C., & Kleintjes, S. (2022). Hearing Their Voices: Self Advocacy Strategies for People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa. Disabilities, 2(4), 588-599. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2040042