The Lived Experiences and Perspectives of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Employment in Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. People with ASD in Open Employment

1.2. The Current Study

- To gain perspectives of people with ASD about which supports they find most effective in gaining and maintaining employment.

- To determine how success in employment is measured by employees with ASD themselves.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

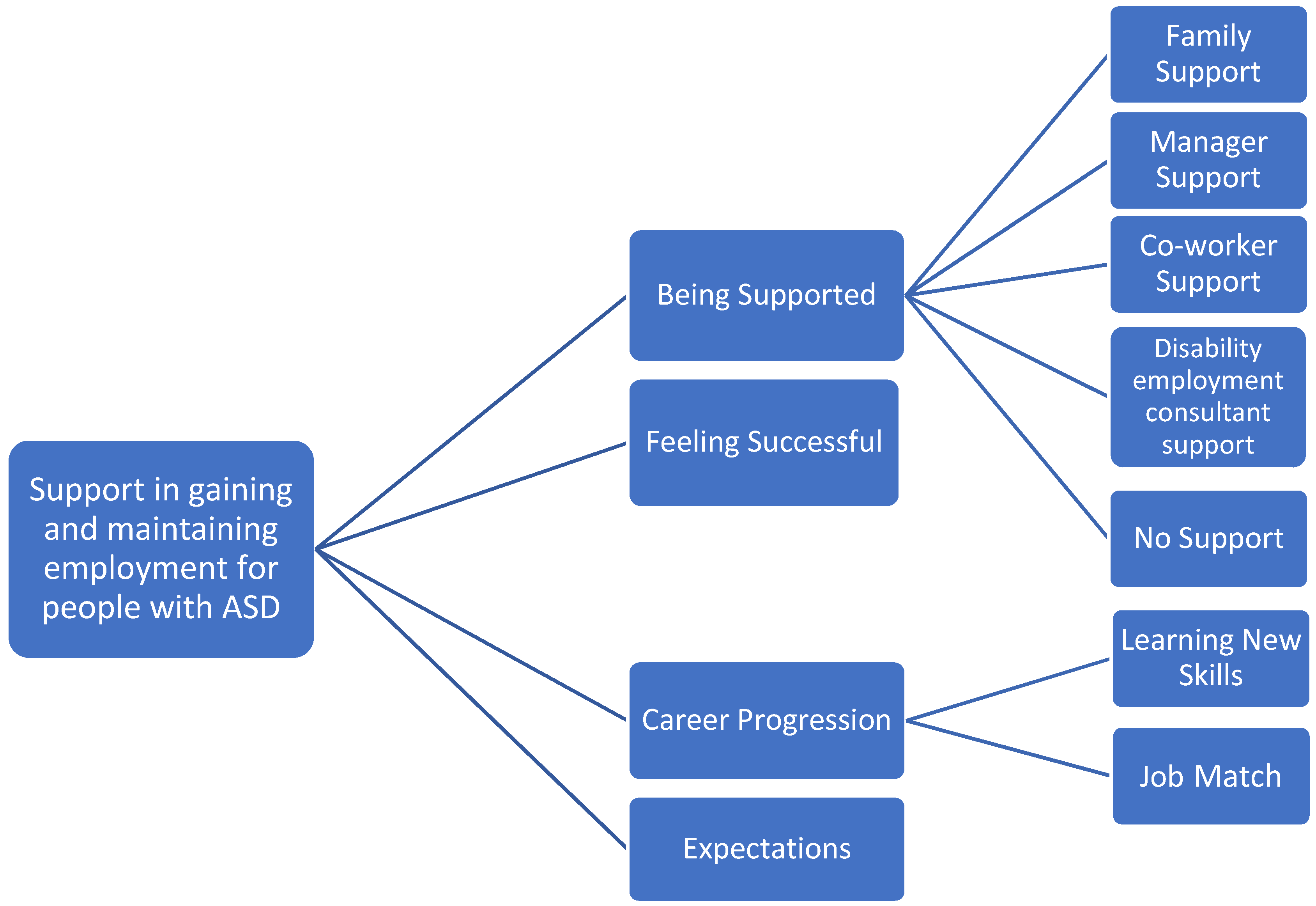

3. Results

3.1. Being Supported

[Manager’s name] which is the lady that gave me the job, she’s really understanding with my weaknesses and strengths.[Participant 8]

“… If I had any problems, like for example, maybe I need to kind of, be shown again how to do something, because maybe I wasn’t confident in doing it. I can ask my supervisor, or maybe someone that has that been [sic] in the job for a long time, just kind of show me like be like OK this is how you do it. And then they show me, and then they would see if I can do it as well”[Participant 5]

So, I’ve made a friend at work. We catch up for lunch every second week. Just for lunch and another friend she used to work with we catch up … We catch up, we socialize, we talk to each other. We hang out. I made a friend.[Participant 1]

With [workplace name] it’s it’s [sic] a bit harder because they have they have they have [sic]. They haven’t requested him coming on to the site. I think. So basically, from what I’ve heard from [disability employment consultant name] is that he does it over the phone, but with the managers to keep up.[Participant 6]

… Problem was, I was taking too long to do it, ‘cause they literally the way that I was set out to be they said they thought [sic] I had had like a few years’ experience, but I hadn’t, and I was hoping to be like at the lower level. But what they were trying to do is they’re trying to get me to take over someone else’s job[Participant 9]

3.2. Feeling Successful

“Uh, just that they are quite reliant on me being able to help the volunteers and stuff … And that they are confident that I know what I’m doing … And that I’m really good at what I do as well”[Participant 8]

3.3. Career Progression

3.4. Expectations

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiarotti, F.; Venerosi, A. Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Worldwide Prevalence Estimates Since 2014. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, M.; Sciberras, E.; Brignell, A.; Ihsen, E.; Efron, D.; Dissanayake, C.; Williams, K. Autism spectrum disorder: Presentation and prevalence in a nationally representative Australian sample. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendse, E.M.; Hendriks, M.P.H.; Thoonen, G.; Aldenkamp, A.P.; Kessels, R.P.C. Social behaviour and social cognition in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Two sides of the same coin? Cogn. Process. 2018, 19, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.L.; Leader, G.; Sung, C.; Leahy, M. Trends in employment for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the research literature. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, E.; Schuler, A.; Burton, B.A.; Yates, G.B. Meeting the vocational support needs of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2003, 18, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, A.M.; Shattuck, P.T.; Cooper, B.P.; Anderson, K.A.; Wagner, M.; Narendorf, S.C. Postsecondary employment experiences among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, M.; Milbourn, B.; Falkmer, M.; Black, M.; Bölte, S.; Halladay, A.; Lerner, M.; Taylor, J.L.; Girdler, S. Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism 2019, 23, 869–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.D.; Nye, C.; Fong, C.J.; Wan, J.T.; Cortopassi, T.; Martin, F.H. Adult employment assistance services for persons with autism spectrum disorders: Effects on employment outcomes. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2012, 8, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvery, M.; Froude, E.H.; Foley, K.R.; Trollor, J.N.; Arnold, S.R. Employment profiles of autistic adults in Australia. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2061–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. 2018. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/4430.0Main%20Features102018?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4430.0&issue=2018&num=&view=2019 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- NDIS. Employment Outcomes for NDIS Participants: Summary Report (as at 31 December 2020); Australian Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2020.

- Hedley, D.; Uljarević, M.; Cameron, L.; Halder, S.; Richdale, A.; Dissanayake, C. Employment programmes and interventions targeting adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Autism 2017, 21, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Sickness, Disability and Work. Breaking the Barriers. Synthesis Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.J. A Systems Analysis of Factors That Lead to the Successful Employment of People with a Disability. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, S.; Costley, D.; Warren, A. Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, E.; Bartley, M.; Shelton, N.; Sacker, A. Do labour market status transitions predict changes in psychological well-being? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowery, L.A. Perceived Benefits of Common Educational and Employment Supports for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7211505109p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, C.; Hauser, W.; Rhein, T. Is any job better than no job? Life satisfaction and re-employment. J. Labor Res. 2010, 31, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villamisar, D.; Wehman, P.; Navarro, M.D. Changes in the quality of autistic people’s life that work in supported and sheltered employment. A 5-year follow-up study. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2002, 17, 309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kamerāde, D.; Wang, S.; Burchell, B.; Balderson, S.U.; Coutts, A. A shorter working week for everyone: How much paid work is needed for mental health and well-being? Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 241, 112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, D. Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorders: Challenges and strategies for success. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.H.; Mahdi, S.; Milbourn, B.; Scott, M.; Gerber, A.; Esposito, C.; Falkmer, M.; Lerner, M.D.; Halladay, A.; Ström, E. Multi-informant international perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to employment for autistic adults. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.H.; Mahdi, S.; Milbourn, B.; Thompson, C.; D’Angelo, A.; Ström, E.; Falkmer, M.; Falkmer, T.; Lerner, M.; Halladay, A. Perspectives of key stakeholders on employment of autistic adults across the United States, Australia, and Sweden. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzeminska, A.; Härtel, C.E.; Carrero, J.; Samayoa Herrera, X. Autism @ Work: New Insights on Effective Autism Employment Practices from a World-First Global Study. Executive Summary. Brisbane. Autism CRC. 2020. Available online: www.autismcrc.com.au (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Ilyes, E. I just wondered if I can do things on my own and don’t have nobody tell me what I can and cannot do. I know better: Letters to the world from inside of a segregated sheltered workshop. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2016, 2, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.; Robinson, S.; Fisher, K.R. Barriers to finding and maintaining open employment for people with intellectual disability in Australia. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1321.0 Small Business in Australia, 2001; ABS: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2002.

- Darcy, S.; Collins, J.; Stronach, M. Australia’s Disability Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: Experiences of People with Disability with Microenterprises, Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship; UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A87165 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Hutchinson, C.; Lay, K.; Alexander, J.; Ratcliffe, J. People with intellectual disabilities as business owners: A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehman, P.; Brooke, V.; Brooke, A.M.; Ham, W.; Schall, C.; McDonough, J.; Lau, S.; Seward, H.; Avellone, L. Employment for adults with autism spectrum disorders: A retrospective review of a customized employment approach. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Avellone, L.; Cimera, R.; Brooke, V.; Lambert, A.; Iwanaga, K. Cost-benefit analyses of employment services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A scoping review. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2021, 54, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehman, P.; Taylor, J.; Brooke, V.; Avellone, L.; Whittenburg, H.; Ham, W.; Brooke, A.M.; Carr, S. Toward competitive employment for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities: What progress have we made and where do we need to go. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2018, 43, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, S. A qualitative study of supported employment practices in Project SEARCH. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 67, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Falkmer, M.; Girdler, S.; Falkmer, T. Viewpoints on factors for successful employment for adults with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139281. [Google Scholar]

- Dreaver, J.; Thompson, C.; Girdler, S.; Adolfsson, M.; Black, M.H.; Falkmer, M. Success factors enabling employment for adults on the autism spectrum from employers’ perspective. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagner, D.; Cooney, B.F. “I do that for everybody”: Supervising employees with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2005, 20, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagraves, K. Effective Job Supports to Improve Employment Outcomes for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Appl. Rehabil. Couns. 2021, 52, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, H.C.; Grabanski, J.; Fischer, D. Supporting adults with Asperger syndrome in the workforce: Implications for higher education practices. Mark. Manag. J. 2016, 2016, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.; Jacob, A.; Hendrie, D.; Parsons, R.; Girdler, S.; Falkmer, T.; Falkmer, M. Employers’ perception of the costs and the benefits of hiring individuals with autism spectrum disorder in open employment in Australia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, C.J.; Taylor, J.; Berdyyeva, A.; McClelland, A.M.; Murphy, K.M.; Westbrook, J.D. Interventions for improving employment outcomes for persons with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review update. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, e1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausa, V.C.; Moore, D.W.; Anderson, A. Use of video modelling to teach complex and meaningful job skills to an adult with autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2016, 19, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matua, G.A.; Van Der Wal, D.M. Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. 2015, 22, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.; Cashin, A.; Waters, C.D. A modified hermeneutic phenomenological approach toward individuals who have autism. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, J.A. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Sage Handb. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 179, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Shinebourne, P. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIntosh, M.J.; Morse, J.M. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahan-Oliel, N.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Majnemer, A. Quality of life and leisure participation in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A thematic analysis of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, A.; Galizzi, M. Employment outcomes for young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Rev. Disabil. Stud. 2014, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin, P.; Goode, S.; Hutton, J.; Rutter, M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Klag, M. Critical reflections on employment among autistic adults. Autism Adulthood 2020, 2, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Zwicker, J.; Clarke, M.E.; Lamsal, R.; Stoddart, K.P.; Carroll, C.; Muskat, B.; Spoelstra, M.; Lowe, K. Evaluation of employment-support services for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017, 22, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.; Fossey, E.; Harvey, C. Moving clients forward: A grounded theory of disability employment specialists’ views and practices. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J. The State of On-the-Job Training in Australian Disability Employment Services: Implications for Policy and Practice; Flinders University: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, J.D., IV; Fisher, M.H.; Brodhead, M.T. Preparing Job Coaches to Implement Systematic Instructional Strategies to Teach Vocational Tasks. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, E.E.; Burke, K.M.; Shogren, K.A.; Wehmeyer, M.L. Promoting self-determination and integrated employment through the self-determined career development model. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2017, 2, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M. The productivity fallacy: Why people are worth more than just how fast their hands move. J. Pediatr. Matern. Fam. Health-Chiropr. 2010, 36, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Grenawalt, T.A.; Brinck, E.A.; Kesselmayer, R.F.; Phillips, B.N.; Geslak, D.; Strauser, D.R.; Chan, F.; Tansey, T.N. Autism in the workforce: A case study. J. Manag. Organ. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, J.; Freedman, B.; Pini, K.; Lloyd, R. Autistic Input in Social Skills Interventions for Young Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Shattuck, P.T.; Cooper, B.P.; Sterzing, P.R.; Anderson, K.A. Social participation among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2710–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzeminska, A.; Austin, R.D.; Bruyère, S.M.; Hedley, D. The advantages and challenges of neurodiversity employment in organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mone, E.M.; London, M. Employee Engagement through Effective Performance Management: A Practical Guide for Managers; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelson, K. “Know thy work and do it”: The rhetorical-pedagogical work of employment and workplace guides for adults with “high-functioning” autism. Coll. Engl. 2015, 77, 553–576. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, A.; Dickinson, H.; Brophy, L.; Kavanagh, A.; Vaughan, C. ‘I don’t think they trust the choices I will make.’–Narrative analysis of choice and control for people with psychosocial disability within reform of the Australian Disability Employment Services program. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job Access. DES Funding. Available online: https://www.jobaccess.gov.au/people-with-disability/des-funding (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Holmes, L.G.; Kirby, A.V.; Strassberg, D.S.; Himle, M.B. Parent expectations and preparatory activities as adolescents with ASD transition to adulthood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2925–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubío-Fungueiriño, M.; Cruz, S.; Sampaio, A.; Carracedo, A.; Fernández-Prieto, M. Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Range | Gender | Employment Type | Role | Length of Employment | Previous Employment | Qualifications 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25–29 | Female | Retail | Back of house, food preparation | 6–12 months |

| Cert 1 & 2 in animal studies Cert 1 & 2 in digital media |

| 2 | 20–24 | Male | Hospitality | Cleaning carpark, restaurant and occasionally serving people, food service | 3–5 years |

| TAFE course in retail (level not specified) |

| 3 | 20–24 | Male | Cabinet Making | Making parts for kitchen bench work | Less than 6 months |

| Cert 3 cabinet making and joinery Responsible serving of alcohol (RSA) |

| 4 | 20–24 | Male | Retail | Cutting and preparing food items for sale | Less than 6 months |

| RSA Cert 1 in tourism |

| 5 | 25–29 | Male | Cleaning | Cleaning offices and office buildings | 6–10 years |

| Cert 2 in kitchen operations Cert 1 in front of house |

| 6 | 25–29 | Male | Food Service | Putting together food orders | 1–2 years |

| Cert 3 in Investigative studies |

| 7 | 25–29 | Male | Hospitality | Back of house, preparing and cooking orders | 6–10 years |

| Cert 2 & 3 in hospitality Barista course |

| 8 | 20–24 | Female | Animal Hospital | Assisting vet nurse and general care of animals | 3–5 years |

| Cert 2 & 3 in animal studies |

| 9 | 30–34 | Male | Cleaning | Cleaning offices and office buildings | 3–5 years |

| Diploma in geo-science |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharpe, M.; Hutchinson, C.; Alexander, J. The Lived Experiences and Perspectives of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Employment in Australia. Disabilities 2022, 2, 164-177. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2020013

Sharpe M, Hutchinson C, Alexander J. The Lived Experiences and Perspectives of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Employment in Australia. Disabilities. 2022; 2(2):164-177. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharpe, Melissa, Claire Hutchinson, and June Alexander. 2022. "The Lived Experiences and Perspectives of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Employment in Australia" Disabilities 2, no. 2: 164-177. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2020013