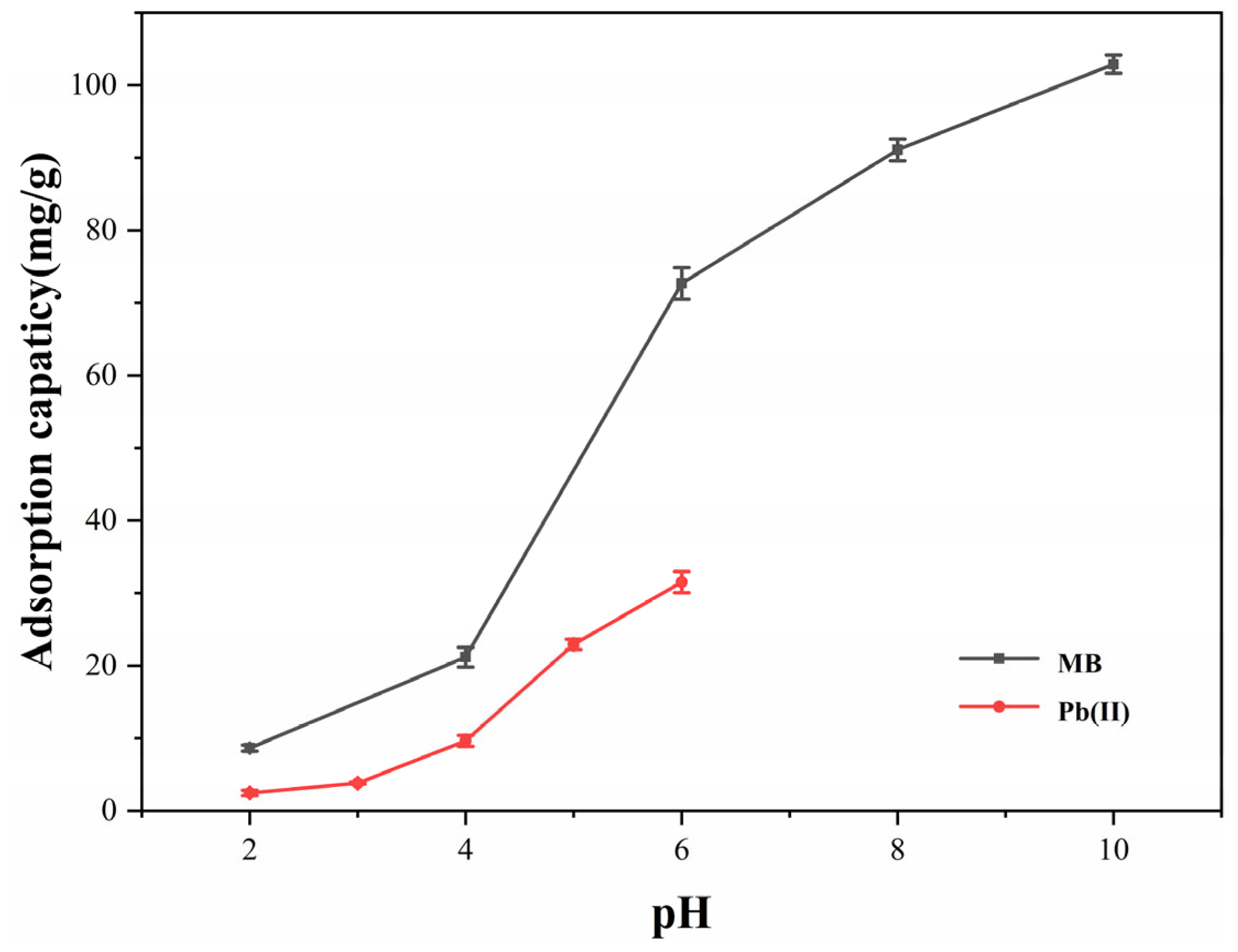

3.1. Impact of pH on Adsorption

Figure 2 illustrates how the Cu-BC adsorption performance for methylene blue and Pb(II) ions is influenced by the initial pH value of the solution. The starting concentration of the methylene blue solution is 100 mg/L, while the concentration of the Pb(II) ion solution is 40 mg/L.

Figure 2 shows that the efficiency of Cu-BC in adsorbing Pb(II) ions progressively improves as pH rises. When the pH increases from 2.0 to 6.0, Cu-BC’s adsorption capacity for Pb(II) ions increases from 2.46 mg/g to 31.52 mg/g. In the meantime, the adsorption capacity of Cu-BC for methylene blue rose from 8.65 mg/g to 102.89 mg/g as the pH rose from 2 to 10, indicating that the adsorption performance of Cu-BC for methylene blue also increased gradually as the pH rose. As a result, Cu-BC’s ability to adsorb MB and Pb(II) ions depends on pH.

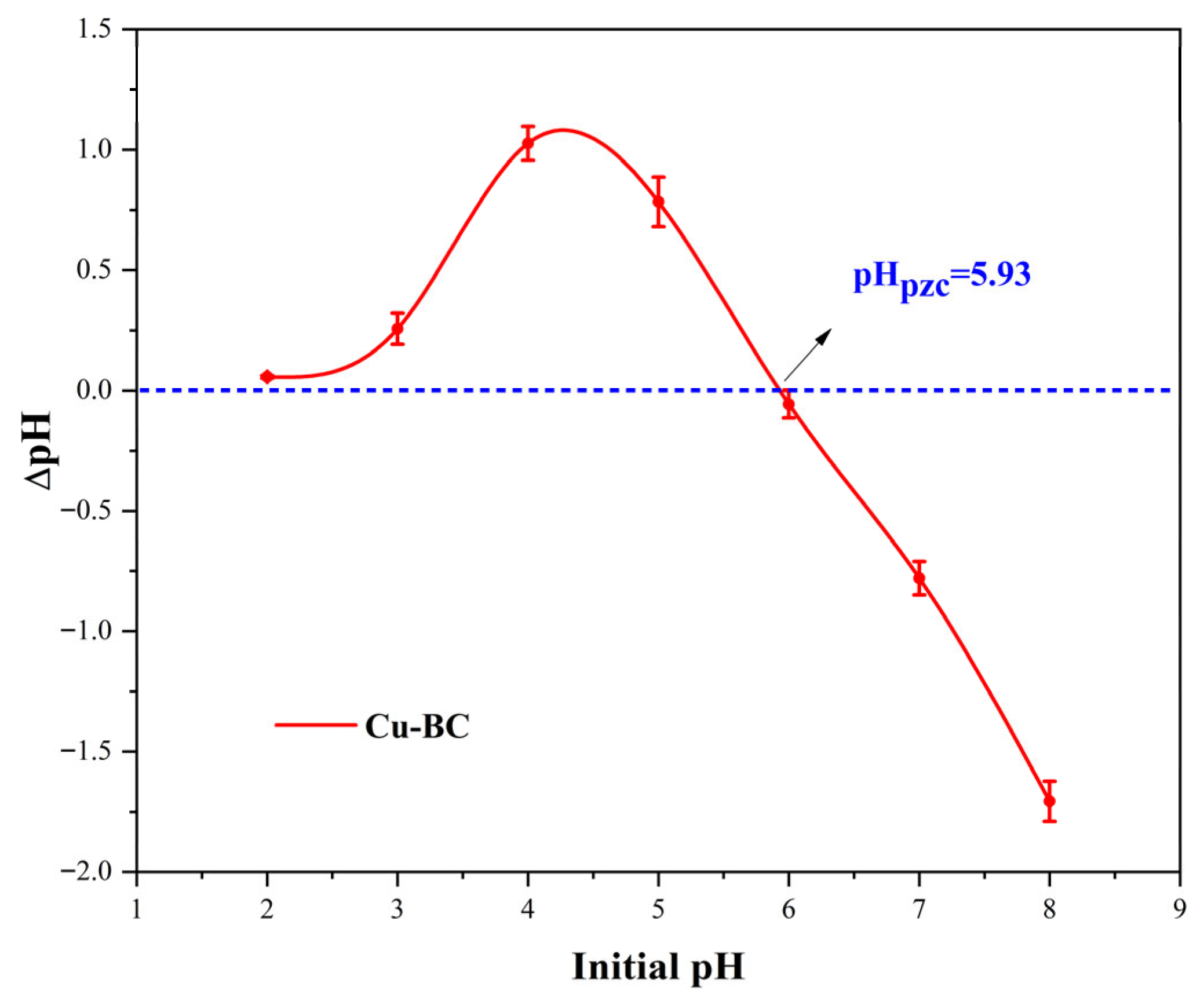

As illustrated in

Figure 3, when the pH of the solution falls below 5.93, the Cu-BC surface in the solution exhibits a positive charge. This may be attributed to the protonation of surface functional groups under low pH conditions, resulting in the acquisition of a positive charge [

17]. The positively charged Pb(II) ion will experience electrostatic repulsion with MB and Cu-BC when the pH of the solution is less than 5.93 [

18], which will affect the adsorption performance of Cu-BC. As the pH rises, the Cu-BC surface’s negative charge increases, facilitating the electrostatic adsorption of MB and positively charged Pb(II) ions. Therefore, the adsorption of Pb(II) ions and methylene blue by Cu-BC was enhanced with the increase in pH, and this trend indicates the inclusion of electrostatic interactions in the adsorption process.

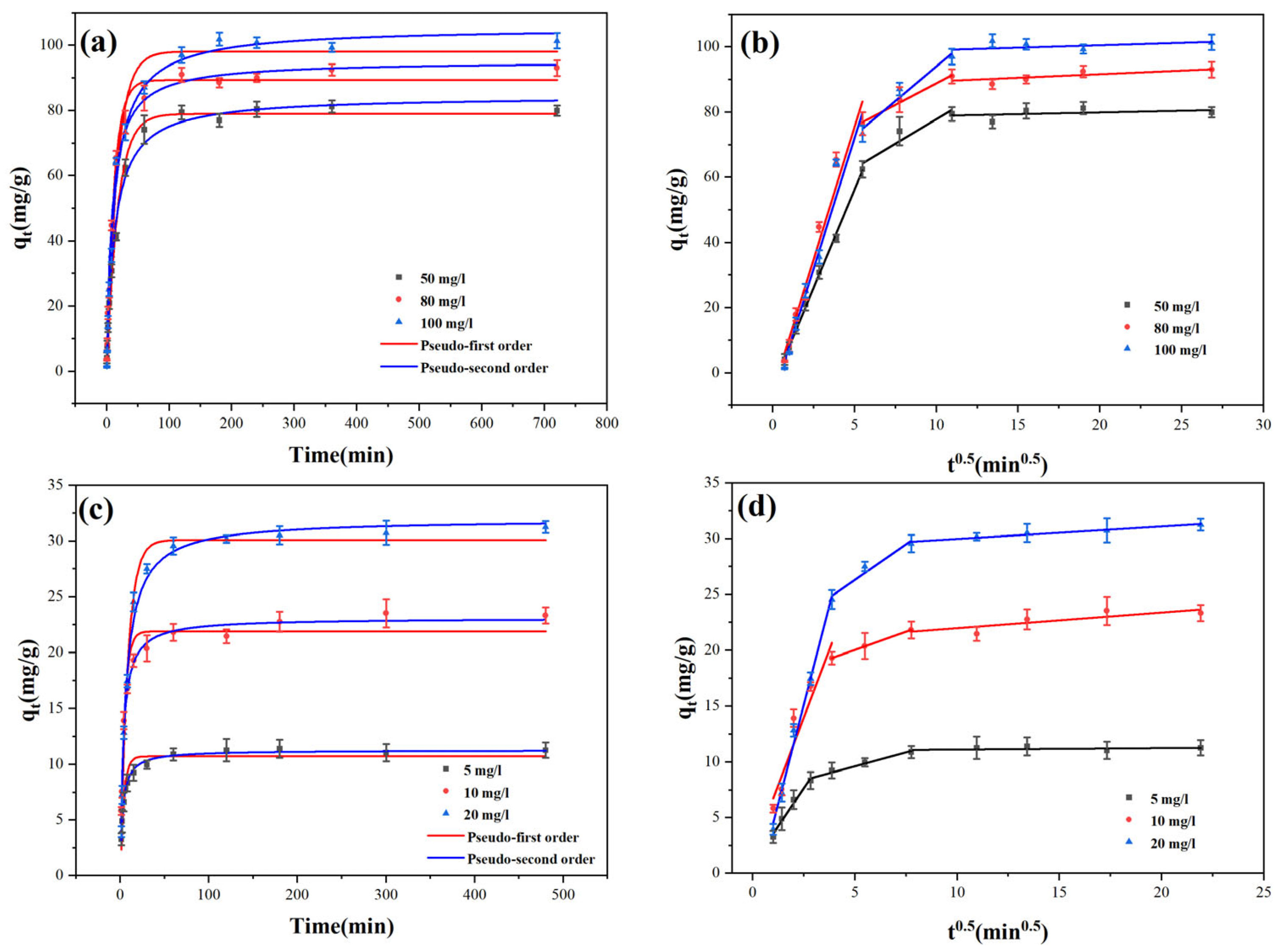

3.2. Adsorption Kinetics

Further fitting of the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, and the intraparticle diffusion kinetic model was performed on the adsorption data of methylene blue and Pb(II) ions.

Figure 4 displays the fitting findings, while

Table 3 and

Table 4 provide a summary of the kinetic parameters of the relevant models. According to

Figure 4a,c, Pb(II) ions and methylene blue on Cu-BC were adsorbed rapidly during the first 15 and 30 min, indicating that the active site on the Cu-BC surface was rapidly bound to MB and Pb(II) ions in a short time. From 120 to 180 min, the adsorption of Pb(II) ions and MB by Cu-BC increased gradually. After 200 min, it tended towards equilibrium. This indicates that the contaminant’s binding is gradually saturated, and the limited binding site on Cu-BC is gradually occupied. The adsorption capacity of Cu-BC, however, rose when the concentration of Pb(II) ionic solution and MB solution increased, according to the kinetic data at various initial concentrations. The adsorption capacity of MB increased from 79.89 ± 1.54 mg/g to 101.44 ± 2.33 mg/g, and the adsorption capacity of Pb(II) increased from 11.26 ± 0.69 mg/g to 31.26 ± 0.52 mg/g. However, with the continuously increasing concentration, the adsorption capacity will eventually reach an upper limit because the binding site of Cu-BC is limited.

According to

Table 3 and

Table 4, the PSO of Cu-BC adsorption of methylene blue and Pb(II) ions has higher R

2 values compared to the first-order kinetic model. This implies that Cu-BC’s adsorption behavior is more in line with the PSO and that chemical interaction regulates the adsorption rate [

19]. The intraparticle diffusion model fitting results (C ≠ 0, with the regression line not going through the origin) indicate that while chemisorption contributes to the adsorption process, it is not the sole governing mechanism, while diffusion mechanisms are also operating simultaneously [

20,

21]. The adsorption data are divided into three straight lines, indicating that there are three different stages in the adsorption process of MB and Pb(II) ions by Cu-BC. In the first stage, MB and Pb(II) ions diffuse from the liquid phase to the outer surface of Cu-BC. The maximum k

1 value indicates that the rate of this process is the fastest [

22,

23]. In the second stage, impurities from the exterior spread within Cu-BC’s pores and into its inside. The k

3 value of the third stage is quite minimal, indicating that at this time, the adsorption operation has basically established the equilibrium. This sequential progression demonstrates that while chemisorption dominates the overall mechanism, the adsorption rate is jointly influenced by both surface reaction kinetics and mass transport limitations [

24].

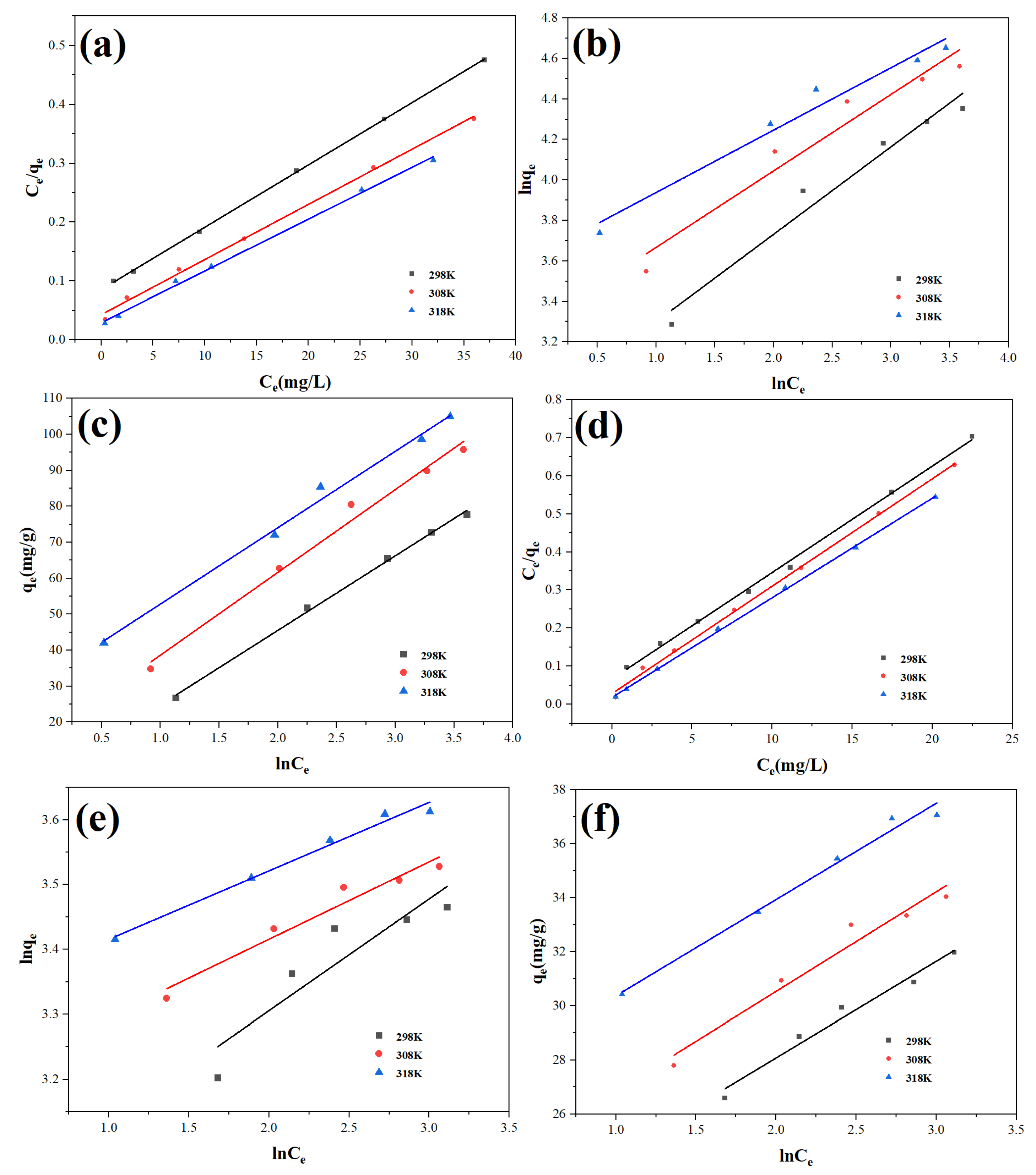

3.3. Adsorption Isotherm

The adsorption data at 25 °C, 35 °C, and 45 °C were analyzed using an isotherm technique in order to further forecast the adsorption of MB and Pb(II) ions on Cu-BC. The Langmuir model can prove the occurrence of mono-layer adsorption, while the Freundlich model can be employed to assess whether the adsorption process is multi-layer, and the Temkin model can identify whether the adsorption process is chemisorbed [

25].

Figure 5 displays the isotherm’s fitting findings, and

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide a summary of the corresponding values for the three models. Among the three models, the Langmuir model has the highest R

2, and the Langmuir model most closely matches the adsorption data, exhibiting that the adsorbed MB and Pb(II) ions are monolayers on the Cu-BC surface, as well as even adsorption sites on the surface [

26]. As the temperature rose, Cu-BC’s adsorption efficiency for Pb(II) and methylene blue (MB) ions increased. At 25 °C, 35 °C, and 45 °C, the highest adsorption capacities (q

m) were measured at 94.43, 106.72, and 113.64 mg/g for MB, and 35.79, 36.06, and 38.24 mg/g for Pb(II), respectively, demonstrating improved adsorption efficiency with increasing temperature [

2,

27]. The R

L values of MB were 0.0746, 0.617, 0.04305, 0.3765, and 0.032, 0.3982, respectively, and the R

L values of Pb(II) ions were 0.046, 0.056, 0.322, 0.0245, 0.167, 0.0672 and 0.017, 0.1218, indicating that their adsorption process on Cu-BC was easy [

28]. The R

2 value of the Temkin model is second only to the Langmuir model, which works very well, indicating that the adsorption process involves electrostatic interaction [

23,

29].

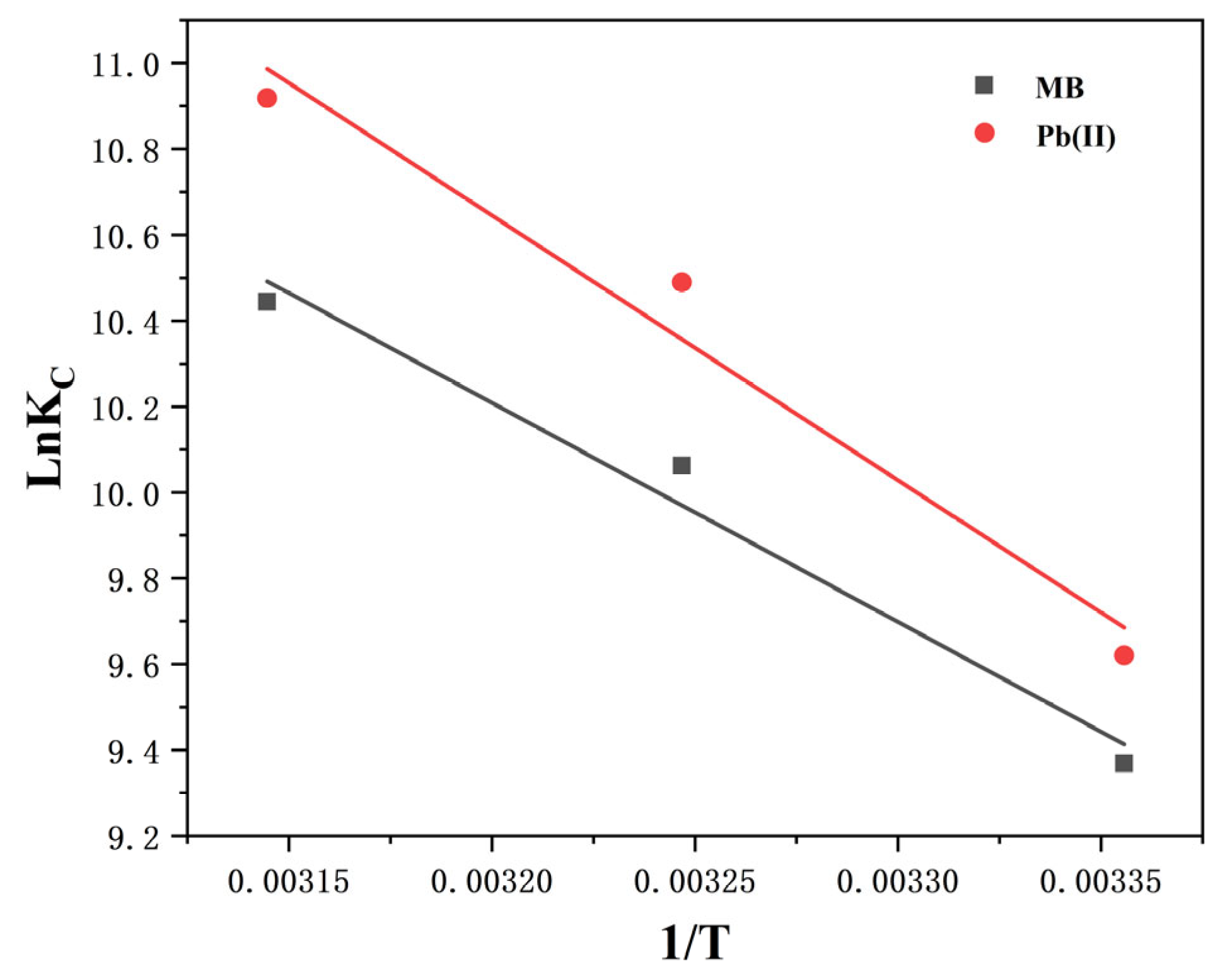

The thermodynamic parameters (∆G°, ∆H°, and ∆S°) derived from the temperature-dependent Langmuir isotherm fits are shown in

Table 7, the regression results of which are graphically displayed in

Figure 6. At 25 °C–45 °C, the ∆G° of Pb(II) ions and MB are negative, indicating that their adsorption on Cu-BC is a spontaneous process [

30]. The key is that a positive ∆H° value indicates that these spontaneous processes are essentially endothermic [

31]. This phenomenon—the coexistence of spontaneity and endothermic properties—reveals a key physical and chemical essence: the driving force of this adsorption process is not energy release, but entropy increase. A positive ∆H° indicates the need to absorb energy to overcome certain energy barriers, which is likely related to the dehydration process of adsorbate ions or solute molecules before adsorption [

32,

33]. Therefore, the spontaneity of the entire process (∆G° is negative) is achieved by favorable entropy increase (∆S° is positive), which offsets unfavorable enthalpy terms. Additionally, as the temperature rises, their ∆G° value decreases, indicating that the temperature pushes Cu-BC adsorption, specifically the Cu-BC adsorption capacity of MB and Pb(II) ions, enhancing with the temperature.

The maximal adsorption capacities (q

m) of several adsorbents for Pb(II) and MB in aqueous solutions are shown in

Table 8. It is clear that Cu-BC has a beneficial effect on Pb(II) and MB, two water pollutants.

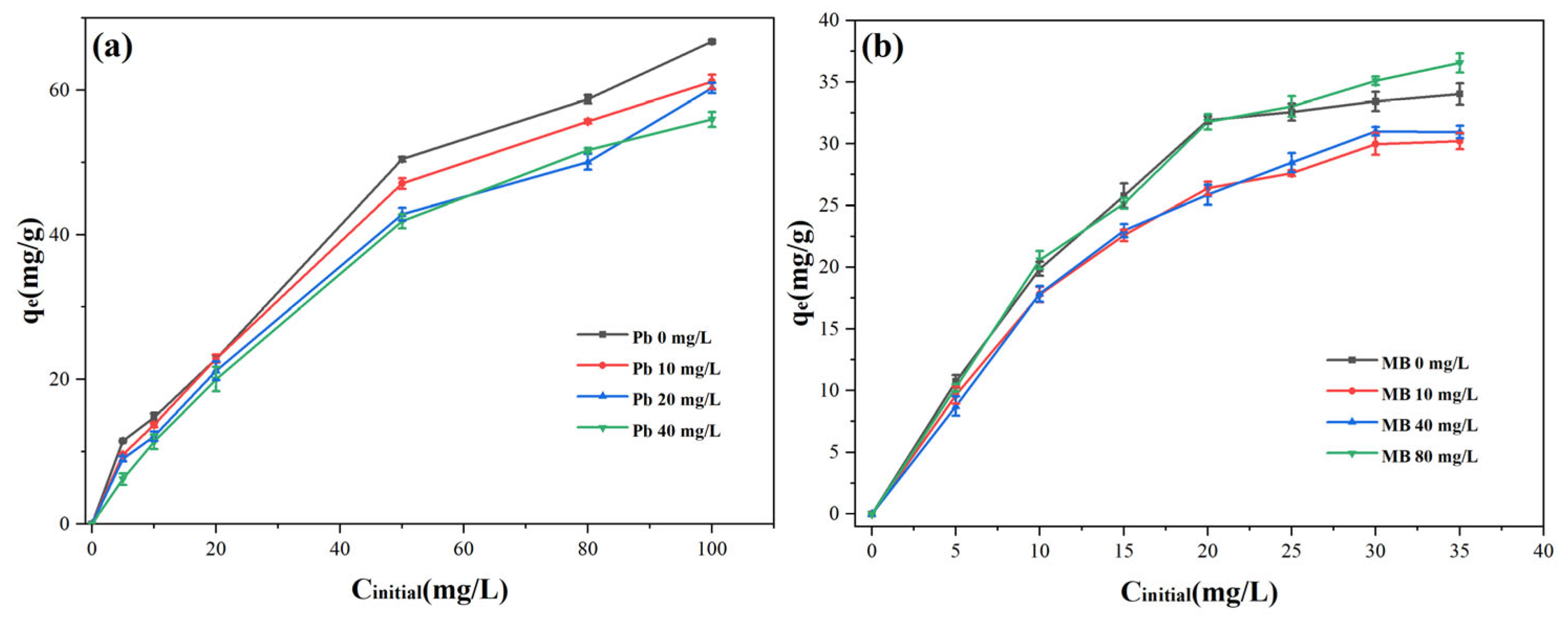

3.4. Adsorption Properties Under the Binary System

Dye and heavy metals usually coexist in dyeing effluents. The MB and Pb(II) coexistence system was examined with the aim of looking into the adsorption capabilities of Cu-BC on dye effluent. The potential interaction between MB and Pb(II) ions may alter Cu-BC’s adsorption ability when they coexist. To assess competitive adsorption behavior, co-adsorption studies were systematically conducted in binary-component systems. The outcomes of the simultaneous adsorption of Cu-BC under a binary system are displayed in

Figure 7. The addition of Pb(II) ions hindered Cu-BC’s adsorption capacity on MB (

Figure 7a), resulting in a maximum adsorption capacity drop of 20%. The mechanisms of site competition and electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged species (MB and Pb(II)) work together to produce this inhibitory effect [

3]. Interestingly, the ability of Cu-BC to absorb Pb(II) ions after the addition of MB was initially inhibited, but later improved as the concentration of MB continued to increase (

Figure 7b). This is because MB adsorbed on Cu-BC has nitrogen-containing groups that can complex Pb(II) ions, thus providing a new site for adsorption [

38]. Overall, in binary systems, methylene blue inhibits the adsorption of Pb(II) ions at low concentrations but promotes it at high concentrations, whereas Pb(II) ions inhibit the adsorption of methylene blue on Cu-BC [

39,

40].

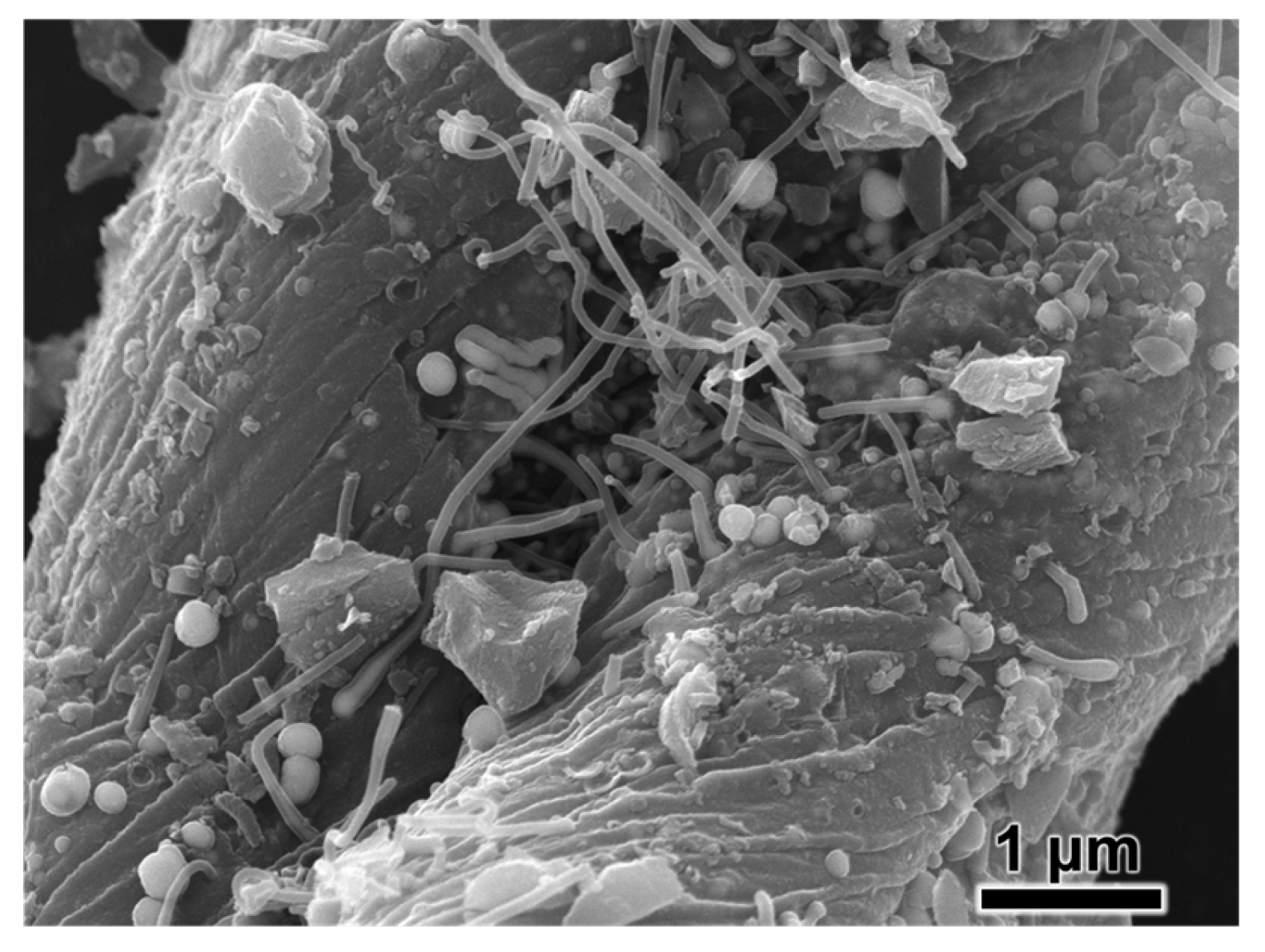

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

MB and Pb(II) ion adsorption on Cu-BC is a complicated process. As shown in the SEM image (

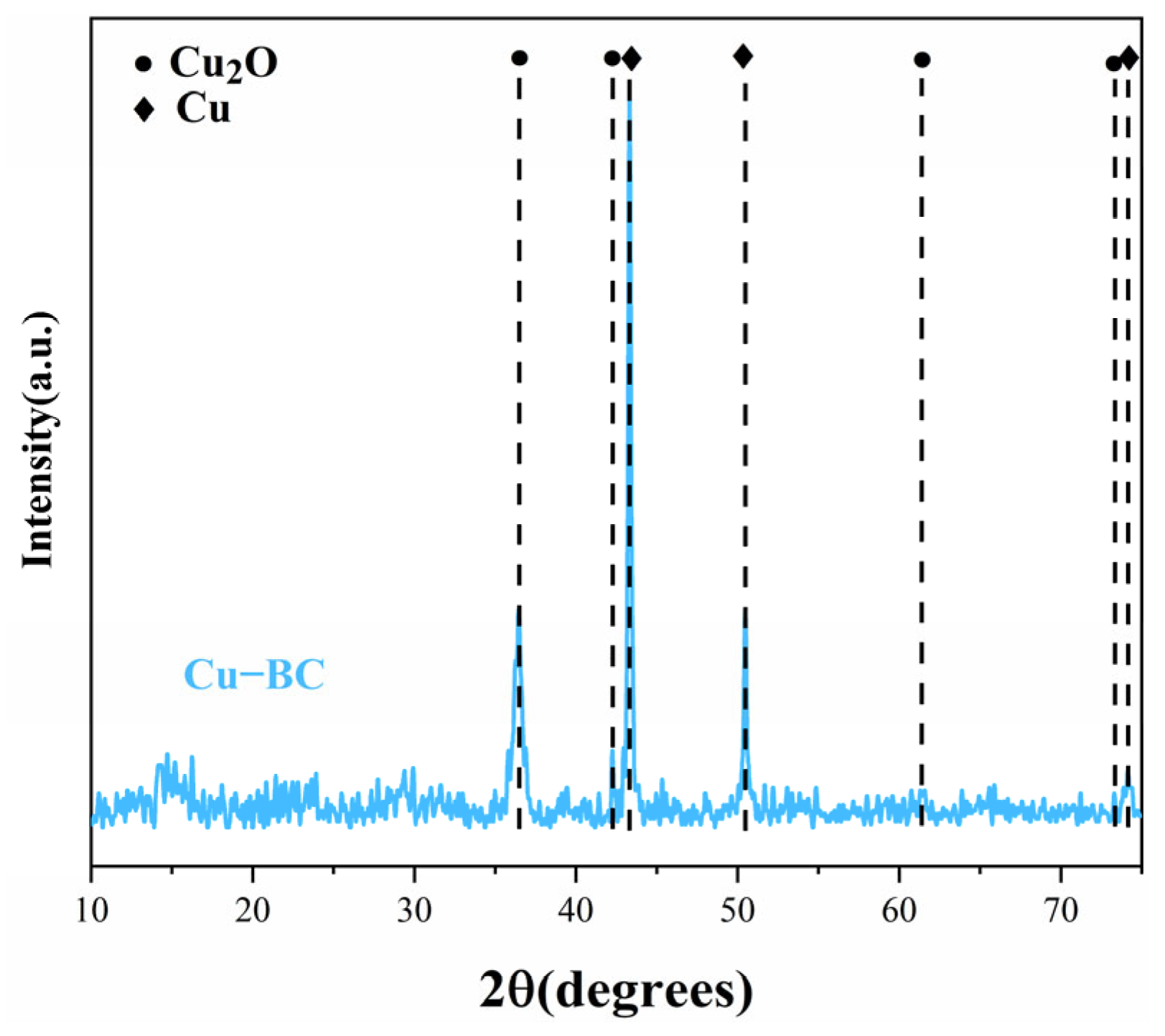

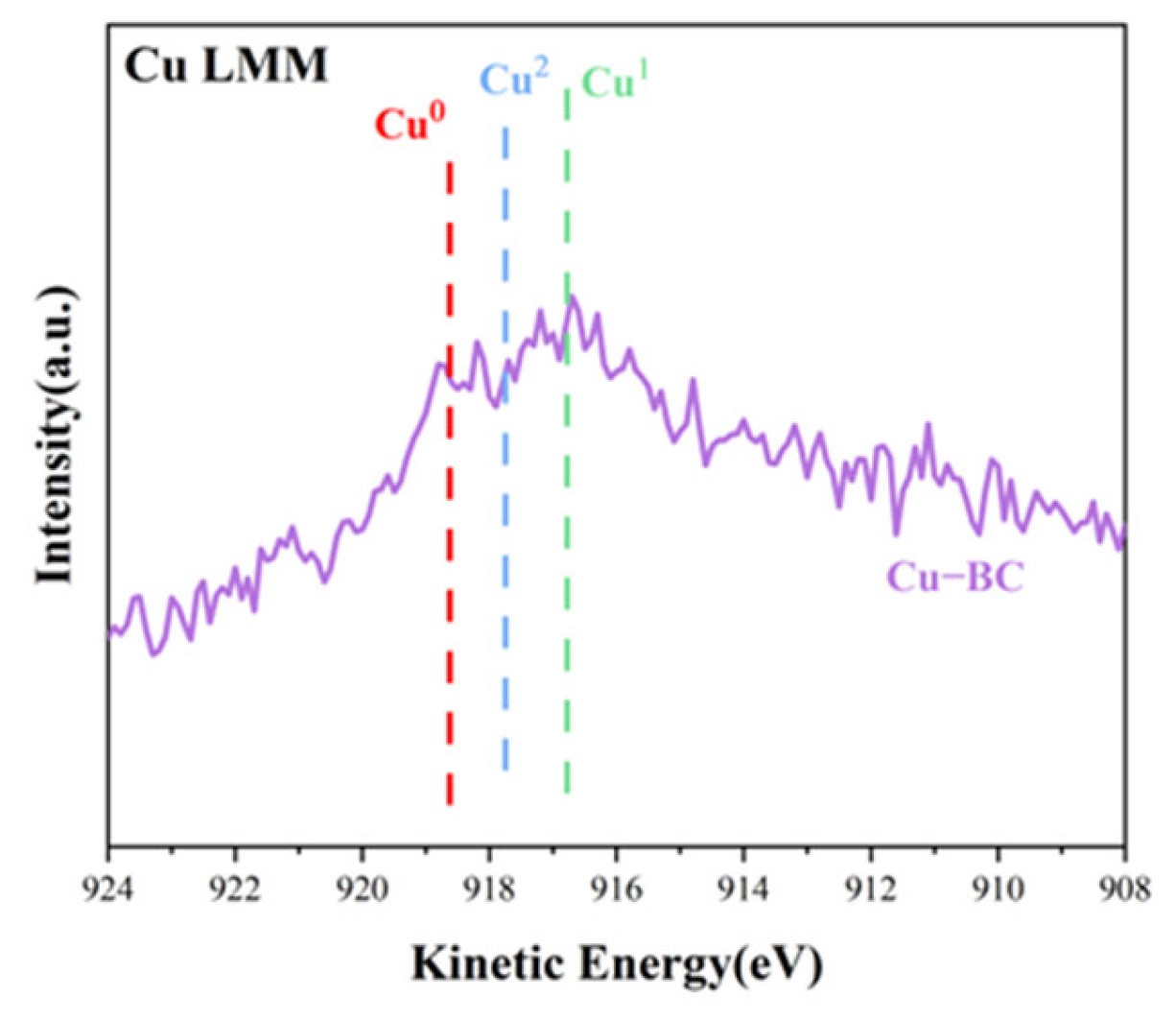

Figure 8), a large number of small white balls are evenly dispersed on the surface of Cu-BC. According to the XRD results (

Figure 9) and Cu LMM results (

Figure 10), these small white balls are various forms of copper (metal Cu0, Cu2O, and CuO), which may promote the photocatalytic degradation of MB [

6,

41], thus enhancing the removal of MB. However, the narrow and winding gaps and large holes of the Cu-BC surface indicate that physical adsorption, such as pore filling and surface diffusion, may be one of the most vital adsorption mechanisms of Cu-BC. According to the results of adsorption dynamics, the adsorption process of MB and Pb(II) ions on Cu-BC is dominated by chemisorption. The effect of pH value shows that there is electrostatic interaction between Cu-BC and the contaminant, which is also proved by the result of pH zero point potential (pHPZC) of Cu-BC, and the fitting of the Temkin isotherm model shows that electrostatic interaction is one of the most important forms.

Surface functional groups of Cu-BC before and after adsorption of MB and Pb(II) ions were analyzed via FTIR (Thermo Fischer, Nicolet is5, Waltham, MA, USA, resolution 4 cm

−1, 32 scans, covering wavenumber range 400 cm

−1 to 4000 cm

−1) to monitor changes in peak intensity and position, which reflect vibrational modifications of surface functional groups, thereby elucidating their role in the adsorption process. As shown in

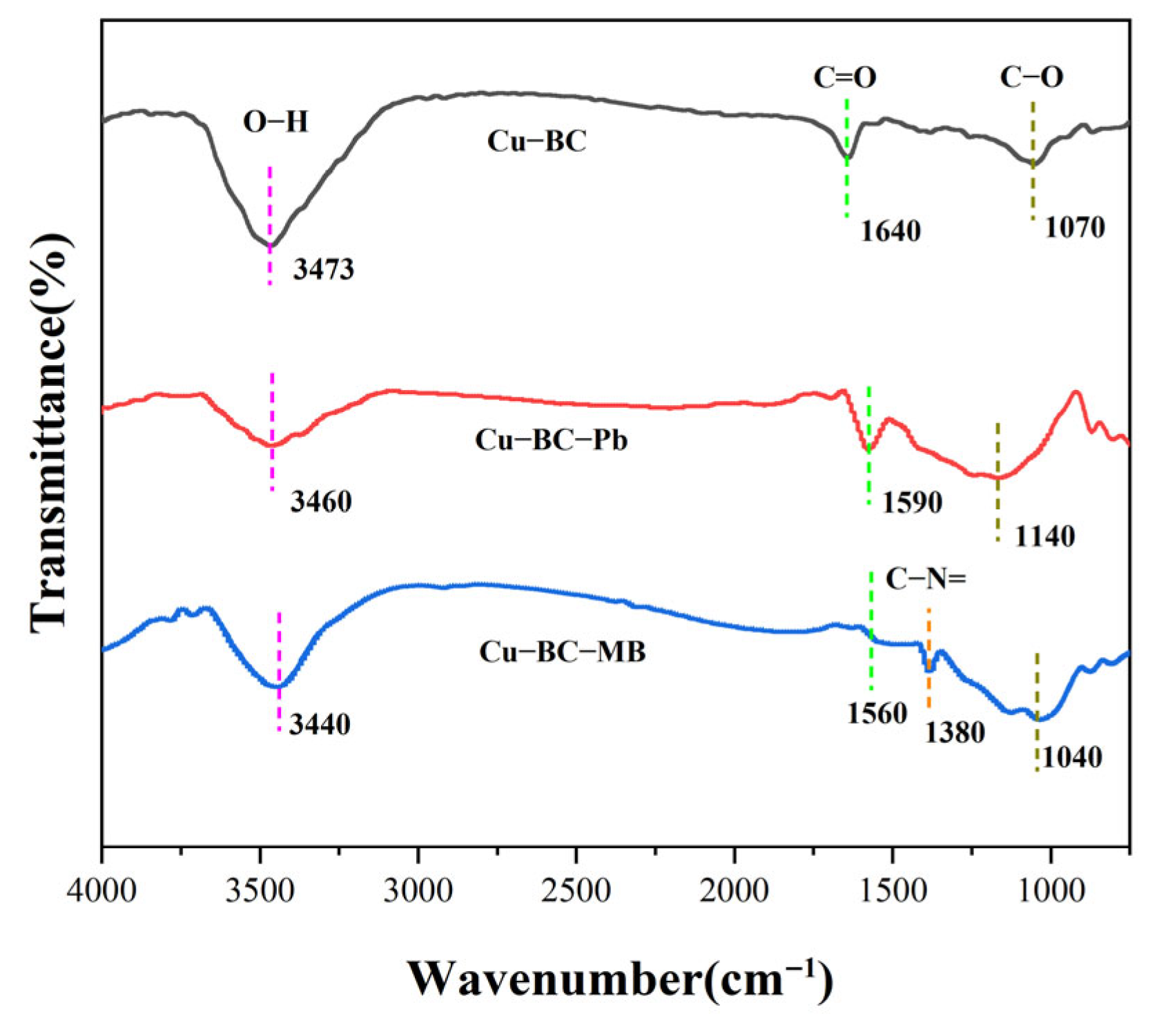

Figure 11, the Cu-BC surface is characterized by functional groups exhibiting peaks at 3473 cm

−1 (O–H stretching), 1640 cm

−1 (C=O stretching), and 1070 cm

−1 (C–O symmetric stretching) [

42]. After Pb(II) adsorption, the C=O stretch red-shifts from 1640 cm

−1 to 1590 cm

−1, indicating coordination between Pb(II) and carbonyl oxygen atoms. Concurrently, the C–O stretching vibration shifts from 1070 cm

−1 to 1140 cm

−1. This shift to a higher wavenumber is attributed to the formation of a stable C–O–Pb coordination bond, which increases the bond force constant [

43]. The broad O–H peak shifting to 3460 cm

−1 further indicates potential involvement of hydroxyl groups in metal complexation [

44]. Following MB adsorption, the C=O peak shifts to 1560 cm

−1, and the C–O peak shifts to 1040 cm

−1. The decrease in wavenumber for the C–O stretch implies a different interaction mechanism, possibly involving π–π interactions or hydrogen bonding with the MB molecule [

45]. The appearance of a new, distinct peak at 1380 cm

−1, assigned to the C–N= stretching vibration of the dye’s aromatic structure [

46], provides direct evidence for the successful loading of MB. The shift of the O–H peak to 3440 cm

−1 also indicates the formation of hydrogen bonds between MB and surface hydroxyls [

47].

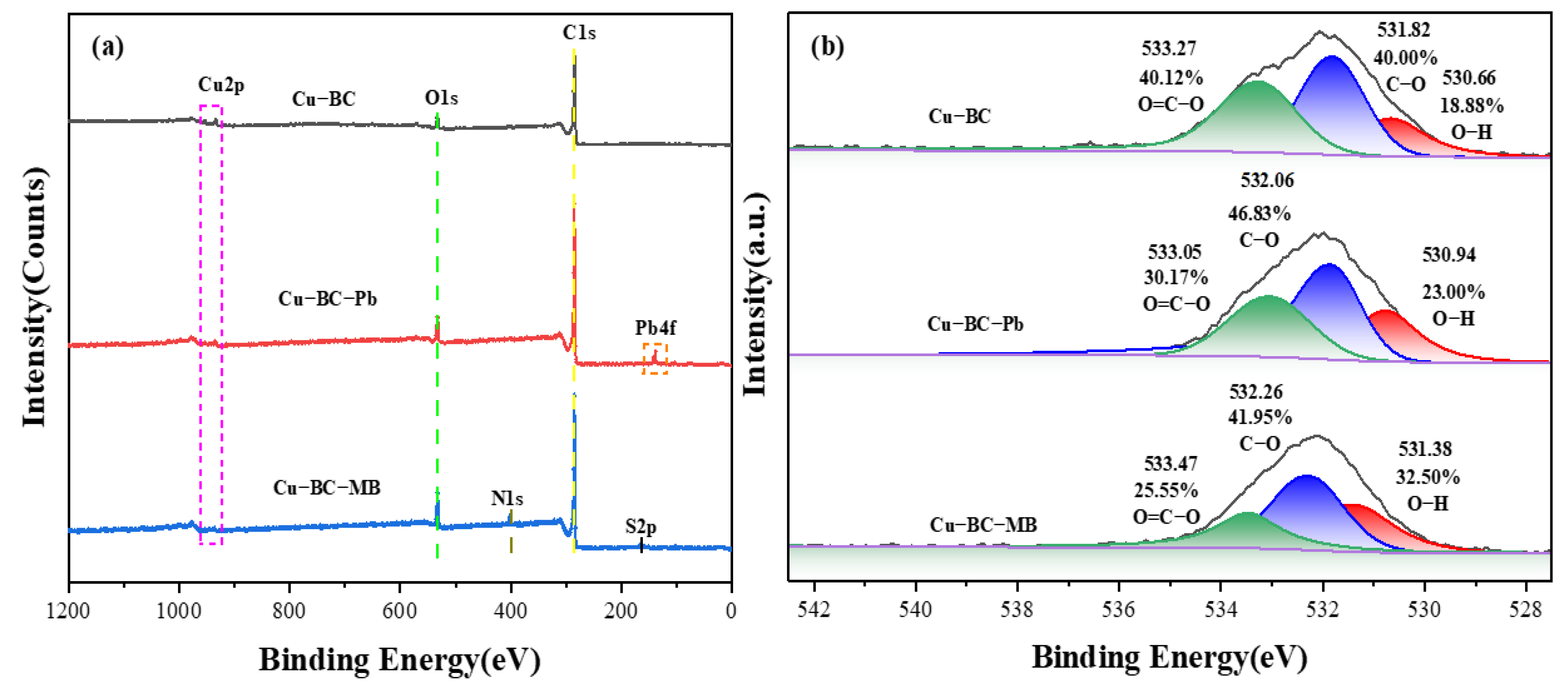

To investigate the adsorption mechanism, XPS was used to further evaluate the chemical properties of Cu-BC during the adsorption of Pb(II) and methylene blue ions. As can be seen in

Figure 12a, the full spectrum of 284.66 eV, 531.82 eV, 932.43 eV, and 952.10 eV correspond to C1s, O1s, and Cu 2 p, separately. Peaks close to the binding energy of 138 eV and 143 eV, which correspond to Pb 4f7/2 and Pb 4f5/2, respectively, are seen following the adsorption of Pb(II) ions [

48], while after the adsorption of methylene blue, a new peak of S2p at 165.2 eV and a binding energy of 400.1 eV at N1s appeared on the full spectrum of the XPS scan. The appearance of these new peaks proves that the Pb(II) ions and methylene blue are successfully adsorbed on the Cu-BC surface. For O1s (

Figure 12b), the peak with binding energy at 530.66 eV on Cu-BC corresponds to OH (18.88%), the peak with binding energy at 531.82 eV corresponds to CO (40.00%), while the peak at 533.27 eV corresponds to O=C–O (40.12%) [

49]. Following adsorption, the OH group’s peaks were moved to 530.94 eV and 531.98 eV, with their relative abundances increasing to 23.00% and 32.50%, respectively; the CO group’s peaks were moved to 532.06 eV and 532.26 eV, with their relative abundances increasing to 46.83% and 41.95%, respectively; and the O=C–O group’s peaks were moved to 533.05 eV and 533.47 eV, with their relative abundances increasing to 30.17% and 25.55%, respectively. These changes indicate that these groups may form hydrogen bonds [

50] or have π–π interaction [

51], and may complex with Pb(II) ions [

52]. This phenomenon is consistent with the FTIR analysis’s conclusions.