Abstract

Contemporary scientific consensus recognizes forests as vital to the global carbon cycle and essential for mitigating climate change and biodiversity loss. Several internationally coordinated forest conservation initiatives were established in the late twentieth century. Market- and rights-based strategies and community-driven participatory reforms have evolved in the fortress forests of the Global South. However, there remains a gap in understanding how these overlapping conservation ideologies—particularly neoliberal, participatory, and fortress conservation—have evolved and interacted within specific geographies. This study investigates the nexus of three conservation ideologies in Myanmar since the 1990s. Using a Marxist materialism perspective and poststructuralist political ecology, we explore how power dynamics in forestry are shifting under neoliberal political philosophy. We show how hegemonic neoliberalism influences the roles of state and non-state actors in Myanmar, where new governance approaches to forest conservation have emerged. New ways of governing forest conservation have emerged in Myanmar, where numerous conservation philosophies have guided the state through global programs, leading to skeletal forest conservation governance. However, these approaches have downplayed Myanmar’s historical and geographical characteristics, both of which are progenitors of its problems in forestry. Our study critiques the contrasting tenets of forest conservation theories to inform future policies.

1. Introduction

In tropical developing countries during the colonial and pre-independence periods, forests were solely managed by state authorities based on excluding locals and maximizing timber production [1]. However, since the 1970s, the conservation of forest resources has received greater attention. Notable international institutions, such as the Brundtland Commission, the International Panel on Climate Change, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), have promoted conservation efforts. Forest conservation in the Global South during the late twentieth century has merged new and old models. Over several decades, state-controlled fortress forest conservation of protected areas, such as national parks, has been the primary method. The core logic of fortress conservation is that local communities threaten forests. Drawing on the environmental and economic rationalities of colonial foresters, this approach holds that local people’s access to and use of the land should be restricted, and that forested areas must be protected by force, if necessary, for sustainable timber production. As a result, exclusionary approaches toward local populations have been applied [2,3]. Despite some successful forest protection initiatives [4], setbacks have arisen due to human involvement, resulting in a review of fortress conservation and the development of community-based conservation (CBC) in forestry. The 1990s CBC outlined a link between biodiversity conservation and local benefits, urging the integration of local community values and their participation in forest management through collective action [5].

Neoliberal strategies for forest conservation with market- and rights-based approaches have also been implemented in recent years. Neoliberal conservation (NC) is based on reimagining the market for conservation through the creation of “natural capital,” using anti-regulation mechanisms and illusionary market promises without guarantees. NC examples include Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus (REDD+) and third-party timber certification schemes. Thus, NC aims to sustain economic growth through “green growth” transformations [6,7]. CBC and NC have been instrumental in shaping forest conservation governance regimes in the Global South. Contemporary literature, however, underemphasizes the interconnectedness of these forest conservation models, leading to a narrow understanding of their forms of emergence and connectivity throughout their evolution. Moreover, a recent report revealed the limited effectiveness of contemporary international forest governance; it proposed a radical “locally based and people-centered” approach to addressing the complexities arising from diverse regional geographies [8,9].

Unfortunately, few studies have addressed the holistic transformation of forest conservation regimes in the Global South, covering all three ideologies of forest conservation outlined above, that is, fortress, community-based, and neoliberal [5]. Most studies focused on a single topic related to one or, at most, two ideologies of forest conservation. They interpreted their results solely within the frameworks of CBC or NC [10,11,12,13]. Understanding holistic transformation is crucial for revealing the interactions, overlaps, and tensions among conservation ideologies in real-world contexts, enabling the development of more adaptive and context-sensitive strategies. It will also contribute to a critical re-examination of contemporary forest conservation schemes in Myanmar, which are often characterized by haphazard approaches shaped by the pursuit of international targets, alongside challenges, such as illegal logging, deforestation, forest degradation, and the exclusion of local communities from the forested land. Therefore, an integrated analysis of the evolution of coexisting forest conservation strategies is essential through a bird’s-eye view. The present study provides a novel analytical approach that embodies the following three significant ideologies of forest conservation: fortress conservation, CBC, and NC. We employ the concept of Foucauldian governmentality, integrating the Marxist materialist approach to highlight why and how the shortcomings of contemporary forest conservation regimes reveal the transformative policy perspective of Myanmar—a country from the Global South [8].

Myanmar’s diverse geography—from snow-capped mountains to dry plains and southern rainforest landscapes—supports a wide range of forest types. The Forest Department classifies the following seven types: mangrove forest, dry forest, scrub and grassland, tropical evergreen, mixed deciduous, deciduous dipterocarp, and hill/temperate evergreen forests. Among these, tropical evergreen, mixed deciduous, deciduous dipterocarp, and hill/temperate evergreen forests account for 86.68% of the total forest area, significantly shaping national management strategies. Before the colonial era, forest use was closely integrated with local communities [2,3]. Colonial administrations, however, redefined forests as economic resources, later incorporating environmental concerns as depletion increased [2]. This shift merged economic, territorial, and ecological rationales, laying the foundation for science-based forestry. Managing forests now required demarcated reserves and protected areas—marking the rise of “fortress forests” in Myanmar [2,3]. Science-based, demarcated forest reserves soon clashed with local communities’ dependence on forest resources [2,3].

However, in recent decades, community forestry and NC have emerged, making Myanmar a key area for studying how global neoliberal environmental politics influence state-led forest conservation. Research on the effects of political transition on forest conservation and conservation as a peacebuilding process has dominated forest policy studies in Myanmar [14,15]. However, no existing studies on Myanmar have addressed the pluralistic interpretation or the evolutionary process of the underlying ideologies of forestry sciences reflected in global conservation rules and authority. Additionally, further research is needed to reveal how neoliberalism shapes and transforms forest conservation governance in Myanmar [16]. Hence, the present study investigates century-old forest management philosophies and emerging discourses on forest conservation, evaluating how conservation governance has been shaped and transformed. We also evaluate the material dimensions of these discourses within the study’s timeline. By doing so, we elaborate the concept of “skeletal forest governance,” referring to an emerging forest governance framework where the three foundations of the framework (i.e., colonial fortress, CBC, and neoliberal models) are pillared. We examine how three dominant ideologies have shaped Myanmar’s forest conservation schemes and collectively form a trilogy foundational to the structure of contemporary forest governance in Myanmar. This article argues that rather than forming a coherent framework, these pillars often conflict and contest one another, highlighting the fragmented and tension-ridden nature of conservation practices in Myanmar. We demonstrate how “skeletal forest governance” in Myanmar was anchored in a foundationalist approach that prioritizes the universal standards associated with each conservation ideology, treating them as a priori principles. Consequently, locally adaptive and context-sensitive strategies are considered secondary or derivative, rather than integral, to the conservation framework.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Forest Conservation in Time of Neoliberal Governmentality: The Nexus of Freedom, Rational Self’s Responsibility, and the Supremacy of Right

This study adopts a Foucauldian approach to governmentality. Foucault described the historical transformation of the state through the theoretical framework—“conduct of conduct” [17]. Neoliberalism has been globally popularized since the 1980s, with Foucault’s concept of governmentality adapted to the term “neoliberal governmentality” [18]. The problem with neoliberalism lies in its attempt to model political power based on political economy principles by introducing the concept of “population” into wealth and economic theory analyses [17]. From the perspective of neoliberal governmentality, the state is rooted in economic freedom. Foucault argued that “the economy produces the legitimacy for the state that is its guarantor” [18] (p. 84). Thus, “the free market, the economically free market binds and manifests the political bonds” [18] (p. 85).

Neoliberalism in forestry and environmental affairs can be analyzed in the following two ways: as a global economic and political project looking to extend market mechanisms and as a mode of governance (neoliberal governmentality) that shapes human thought, calculations, and conduct through market freedom [7,19,20]. These two traditions can be reconciled by incorporating neoliberal foundations and political philosophy. The neoliberal economic project of the “market economy,” centered on market freedom, emerged from deontological liberalism’s conception of the human agent as “the rational self,” prioritizing individual rights over any presupposed collective goods [21,22].

Neoliberal philosophy considers mobilization and security of market freedom as vehicles for individual rights [23,24]. Hayek [25] supported this priority of the rational self by asserting that “liberty” and “responsibility” are inseparable. This neoliberal “responsibility” was in the individual mode [25]. This perspective led to Foucault’s concept of the “arts of government of the economic agents” [7,18]. Therefore, NC runs through the entrepreneurial engines of profit-maximizing economic agents [26,27]. As a result, key neoliberal economic principles—marketization, an enhanced private sector role, deregulation, and voluntarism—emerged, prompting the withdrawal of state responsibilities in forestry [28]. Moreover, NC shapes the “thoughts of forestry actors” to favor market mechanisms, promoting privatized forestry, payments for environmental services, and non-governmental organizations’ involvement through certification programs, thereby hollowing out the state’s responsibility for forest management [7].

2.2. Analytical Framework

Following Paing et al. [16] and Phyu et al. [3,29], we apply Foucauldian genealogy for textual data to examine knowledge production by scrutinizing the effective formation of discourses and their specific norms, conditions of appearance, growth, and variation in forestry, with a focus on forest conservation. This approach tracks the evolution of forestry discourse alongside material terms. The materialism of civil society and the idealism of the state are Marx’s and Foucault’s perspectives, highlighting the evident connection between their works [30]. Hence, the integration of Marxist materialist interpretation and Foucauldian discursive analysis addresses the “unclear provision of discursive and non-discursive effects” in recent environmental policy analysis [31]. From a political ecology perspective, understanding the dynamics of forest conservation governance demands a critical analysis of the dominant discursive frameworks, the production and circulation of forestry and environmental knowledge, and the material configurations through which power is exercised and contested in specific conservation contexts. Therefore, we interpret the intertwined nature of knowledge production and material outcomes by examining the evolution of thoughts in forest management and conservation, and how this has shaped the nature of forestry production, reservation practices, and the dynamics of timber demand and supply, and vice versa (Table 1). Moreover, we show how discursive strategies of fortress and neoliberal efforts created the land transformation (from primitive land accumulation to land accumulation by dispossession) by establishing the private plantation industry [32,33]. The integrity of the two dimensions is made possible via Foucault’s genealogy [16].

Table 1.

Key concepts in this study.

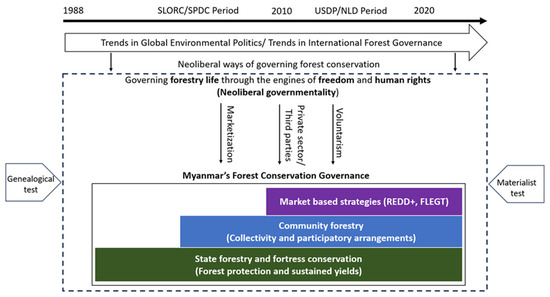

In this study, we examine the relationship between tactics, procedures, and the collective conservation knowledge of the state and those of neoliberal global environmental politics to uncover the conditions of “power relations” shaping conservation practices in Myanmar. We observe how key neoliberal principles—as mentioned previously—penetrate and mutate both discursive and materialist terms [28]. We then outline how these key principles were utilized to maintain the participatory and state forestry responsibilities within a neoliberal governmentality (Figure 1). The analysis was divided into the military period (State Peace and Development Council [SPDC] and State Law and Order Restoration Council [SLORC], 1990–2010) and the democratic transition period (Union Solidarity and Development Party and the National League for Democracy [NLD], 2011–2021). We collected discursive and statistical data from two web portals in Myanmar (www.burmalibrary.org/en (accessed on 15 July 2024) and https://myanmar-law-library.org/law-library/ (accessed on 19 July 2024)), as well as news from local and international newspapers and reports from government institutions, INGOs, local NGOs, and CSOs. In the result section, in-text citations are labeled sequentially as News (Appendix A) for newspapers, RWP (Appendix B) for NGO reports and working papers, and LR (Appendix C) for laws and regulations. We organize the discursive data into the following five major themes: forest management, market systems, communities, forest projects, laws, policies, and regulations. Drawing from these themes, we trace dispersed statements from diverse sources to identify the singularized and regularized points of discursive knowledge that coalesce around the emergent discourse [34,35]. Therefore, we first traced the widely accepted knowledge at each specific point in time within a particular discourse and examined its forms and conditions through a meticulous analysis of statements related to each thematic area. In doing so, we deconstructed and reconstructed the historical evolution of forestry thoughts and, ultimately, the trajectory of forestry knowledge and transformed forestry.

Figure 1.

The analytical framework of the study.

3. Myanmarian State Forestry: A Totalitarian Government in Forest Conservation

3.1. The Dual Logics of Protectionism and Sustainability in Fortress Conservation

“The State is the ultimate owner of all natural resources above and below the ground, above and beneath the waters and in the atmosphere, and also of all the lands (LR 1).” Military governments adopted this notion of a state in the 1990s, under the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP) and its “Burmese Way to Socialism,” the state-controlled forests, forested lands, and associated industries. The BSPP aimed “to prevent pernicious systems characterized by exploitation of man by man, and of one national race by another, all of which emerged from ill-effects of capitalistic parliamentary democracy (LR 1).” Therefore, the state is responsible for its population through state organizations in the natural resource sector. This determination was the rationale for a socialist state governing every sector, including forestry, through a totalitarian government. However, the collapse of the BSPP shifted the state’s focus from exploitation to welfare and improving the population’s living standards. Subsequently, the two military governments (SLORC and SPDC) emerged with neoliberal approaches to their political economy from 1988 to 2010 [16].

To cope with the new “neoliberal market economy,” Myanmar upgraded the existing legal and policy structure of the forestry sector with the Forest Law (1992), the Forest Policy (1995), and the Forest Rules (1995), replacing the older colonial regulatory framework (LR 2). This hybrid structure was intended to support the private timber industry [16]. However, the state was cautious about abolishing fortress conservation in centuries-old forestry and was reluctant to abandon the embedded binary notions of protectionism and the sustainability of German forestry [2]. The leader of SLORC/SPDC—Senior General Than Shwe—reaffirmed the binary nature of forestry as the efficient and sustainable utilization of forest products with protection (LR 3). The state’s intentions in the 1990s were evident, concentrating on timber utilization and forest management, with fortress conservation contributing to the neoliberal market economy. The new challenge became achieving economic and environmental prosperity simultaneously. The new forestry policy of 1995 aimed to create “[…] sustainable and intensive forest management for environmental and economic prosperity of the people of Myanmar as well as to contribute to the amelioration of global environmental issues […] (LR 4).” Forest reservation was “to conserve the environmental factors and to maintain a sustained yield of the forest produce (LR 2).”

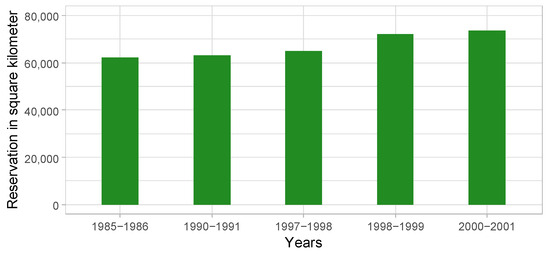

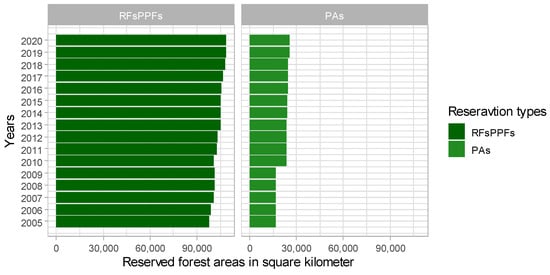

Myanmar also enacted the “Protection of Wildlife and Protected Areas Law” in 1994 to protect local wildlife, designating forest land as protected areas (PAs) for diverse species of flora and fauna (LR 5). Subsequently, the “Permanent Forest Estate” and “Sustainable Forest Management” terminologies were adopted from the International Tropical Timber Organization in the 1990s [16]. The Permanent Forest Estate was categorized into the following three subdivisions: (1) Reserved Forests (RFs), (2) Protected Public Forests (PPFs), and (3) PAs. In 2001, the National Forest Master Plan (NFMP) set total land area reservation targets for RFs and PPFs to 30% and PAs to 10% (LR 6). Following this century-old discursive strategy of protectionist ideas, the Myanmarian state forestry prioritized forest reservations and substantially increased reserved forest areas from 1985 to 2000 (622,962 km to 737,592 km) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The expansion of forest reservation (source: Central Statistical Organization (CSO)).

3.2. Myanmarian Scientific Forest Management Challenges: Totalitarian Management Activities, Supply Deficit, and Illegal Logging

Myanmarian scientific forest management has a unique scientific logic around timber harvesting, where a forest section is divided into 30 blocks to be organized as a felling series over a 30-year felling cycle. The estimated yield is based on minimum girth limits for each block [36]. Thus, Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) is determined by three prime factors—area, girth, and time constraints (LR 7). Working cycle units with working plans were created to implement the Myanmar Selection System (MSS). The Forestry Department (FD) and Dry Zone Greening Department developed 70 district forest management plans, each representing a forest management unit (LR 7). All district forest management plans deal with extraction, conservation, and local engagement by subcategorizing the following seven working circles: (1) production, (2) watershed forest, (3) planted forests, (4) local supply, (5) non-wood products, (6) protected areas, and (7) special (LR 6).

Thus, the two state agencies rationalized, “in governing the forest lands, to encounter the degrading and deforesting issues, forests need to be managed with a gripped, mapped, and demarcated territory to open the possibilities for scientific forest management in protecting biodiversity, flora and fauna, and wildlife while utilizing forestry resources sustainability.” The MSS forest management continued to operate under the fortress model in state forestry. However, the model faces significant challenges due to pre-existing settlements, agricultural activities, and human disturbances, which complicate the management of these forested areas. These complexities have led to the development of extensive yet detailed forestry techniques to effectively engage with and administer local communities (LR 8).

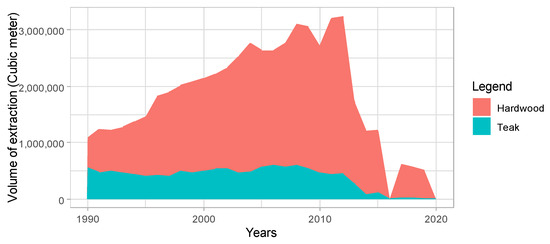

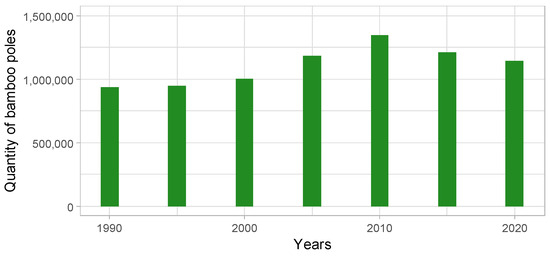

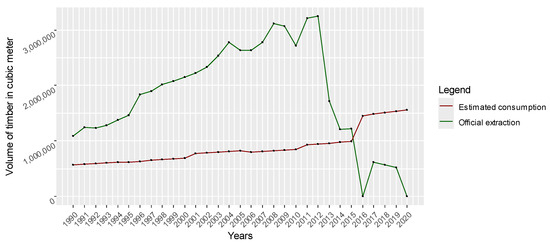

During the democratic transition period, the subsequent Union Solidarity and Development Party and NLD governments were aware of forestry issues and public desire. Meanwhile, the neoliberal discursive strategy of market liberalization, marketization, and the enhanced role of the private sector implemented during the military regimes (SLORC and SPDC) triggered forest depletion and degradation, resulting in a significant decline in the timber supply from natural forests, as reflected in the AAC—from over 300,000 trees in 1990 to 100,000 trees in 2018 (Forest Department, 2020). Subsequently, contemporary forestry research reports informed policymakers of the deteriorating conditions of Myanmar’s forests during the NLD regime [37]. Neoliberal market liberalization of the timber industry led to the severe overexploitation of forests—arguably the worst in Myanmar’s history—as state agencies failed to enforce timber extraction regulations on subcontracted private companies, pressured by neoliberal profit motives and authoritarian regimes (Figure 3) [16]. Not only did timber supply decline, but the booming neoliberal era also triggered a drop in one of the major non-timber forest products—bamboo extraction—after the 2010s (Figure 4). Influenced by deteriorating forest conditions, several workshops were conducted with top forestry officials and retired senior officials. The outcomes of these 2016 workshops under the NLD government were a one-year national logging ban and a ten-year ban in the Bago Mountain range, once known as the “home of teak” (News 1)—a full-scale 10-year reforestation effort—the Myanmar Reforestation and Rehabilitation Program (MRRP) was launched in 2017. The program was the biggest reforestation plan in Myanmar’s history. This initiative, grounded in the 1995 Forest Policy and the NFMP, aimed to develop a comprehensive forest plantation policy (LR 9). Therefore, the combined influence of protectionist knowledge and actual forest conditions catalyzed Myanmar’s most considerable reforestation effort—the MRRP.

Figure 3.

The impacts of neoliberal exploitation (1990–2010) and reduced logging policy on state-managed logging in Myanmar (source: CSO).

Figure 4.

A decline in official bamboo production in Myanmar after the 2010s (source: CSO).

However, the official ban on logging did not prevent illegal logging, which the FD admitted could not be controlled (News 2). Illegal logging in the Pego Mountain range threatens the security of local females working in traditional taungya (News 3). Thus, the FD sought help from concerned citizens through the “Citizen-Based Monitoring System” (RWP 1). However, there were no existing calculations of annual timber consumption or plans by local timber markets to substitute timber for consumption. Myanmar has already suffered an “internal timber supply deficit”, even affecting its urban population (Figure 5). Future yield estimates, such as those given by the AAC, are only available for natural forests and are absent from the state’s century-old plantations, recent private plantations, community forests, and the MRRP program. Between 1981 and 2018, over 0.5 million hectares of state-owned forest plantations were established. However, these plantations have contributed little to easing pressure on natural forests, despite being promoted as indicators of forestry progress (LR 7). Under authoritarian regimes, the Forest Department faced chronic underfunding, with actual payments falling short of approved budgets. As a result, the state-run plantation sector has struggled with low accountability and limited transparency to keep the promise of the program.

Figure 5.

Potential timber supply deficit in Myanmar for urban population (sources: Myanma Timber Enterprise, FAO, UN Population Division, CSO).

3.3. Head-to-Head Conflicts Between “Myanmarian Scientific Forestry” and the “Rights of Man”

Myanmar revised its decades-old Forest Law (1992) with the Forest Law (2018) and revised the Forest Rule (1995) with the Forest Rule (2019). The Protection of Wildlife and Protected Areas Law was updated with the Conservation of Biodiversity and Protected Areas Law. Despite numerous decentralization attempts, fortress conservation in state forestry remains the core of regulation platforms. Moreover, Myanmar still maintains legacy goals for expanding fortress conservation from the NFMP and Forest Policy 1995. The technical knowledge underpinning reservation-based forest protection supported fortress conservation, expanding RFs and PPFs, even amid decentralization efforts, shaping local communities’ reliance on these forests. The FD’s recent attempt to place forested land under the control of the state coincided with the expansion of PAs and National Parks (Figure 6). The people living in the mountainous regions strongly rejected these incremental attempts.

Figure 6.

The gradual increase in the reservation of forested land (source: CSO, FD).

The Hkakabo Razi landscape in northern Kachin State—Myanmar’s last stronghold of diverse ecological nexus and biodiversity with intact natural forests—highlights the tension between fortress conservation and local traditions (News 4). The conflict intensified with the nomination of the area as a World Heritage site with a southern conservation extension reaching over 11,000 km2 to conserve endangered mammals such as tigers in Myanmar. The primary determinant was reaching an agreement with local communities through free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). There were two opposing issues in this conflict. Scientific opinions on state forestry were backed by consensus on biodiversity concerns around globally threatened and data-deficient species (RWP 2). In contrast, the rights-based opinions of the local people were backed by civil society and local NGOs. The Wildlife Conservation Society issued a statement respecting local customs, and progress stagnated (RWP 3).

Critically, both sides recognized the values of human rights and biodiversity conservation. However, the fortress conservation prioritizes the preservation of biodiversity, while locals prioritize the right to free mobility and local community traditions. The latter favors local freedoms (individually and collectively), demanding that the conservation standards align with their traditional freedoms and customary livelihoods (News 5 and 6). Therefore, the idea of fortress conservation, through its discursive strategies of scientific forestry and meticulous standards, elaborated top-down regulations with forestry disciplines, rules, and punishments in governing the forest landscapes [17,18]. However, this form of governing forests bore the internal inability to cope with human rights and market liberalization, revealing its vulnerability to external and global ideologies in forest governance.

4. Community Forestry in Myanmar

4.1. The Evolution of Community Forestry Within State Forestry During the 1990s

Myanmar began to make allowances for local participation in forest management under the 1995 Forest Policy. Among the six imperatives of the 1995 Forest Policy—3.1 Protection, 3.2 Sustainability, 3.3 Basic Needs, 3.4 Efficiency, 3.5 Participation, and 3.6 Public Awareness—3.3, 3.5, and 3.6 sought to engage with the local population. Imperative 3.4 emphasized efficient utilization and marketization with private involvement, while 3.1 and 3.2 upheld colonial state forest management. Imperatives 3.5 and 3.6 sought to engage active and responsible local agents who wish to participate in forest conservation under the guidance of scientific forest management standards. These imperatives are central to defining future forestry goals and strategies (LR 4). Thus, the forestry problematization of the state after the 1990s, with community forestry (CF), centered on the local population and the rights and livelihoods of those living in forested lands. Regardless of these issues, the state did not abolish fortress conservation measures but introduced new strategies to involve local populations in solving problems arising from state forestry. The 1995 Community Forestry Instructions (CFI 1995) sought to bolster the state’s economic development and forest conservation, while persuading the local population to participate (LR 10).

Instead of deregulation, fortress conservation attempted to share basic land and forest product use rights with communities. However, these shared rights often pertained to degraded lands that were difficult to regenerate naturally. The 1990s version of CF was limited to colonial forest management strategies, expanding state authority on “Local Supply/Community Working Cycles” from colonial-era district plans but with decentralized authority (LR 10). Local participation in the program was voluntary; however, this strategy exposed issues of equity and exclusion (RWP 4). The FD maintained control by ensuring every Community Forestry User Group (CFUG) followed a management plan that met state forestry standards. This approach reflects how fortress conservation incorporates strategies to administer local populations while effectively reinforcing scientific forest management principles.

4.2. State Forestry Dominance to Deregulation with Marketization and Human Rights in the CF Program After 2010

This ideal model of state forestry in the CF program was later challenged by local communities based on human and market rights. This shift was facilitated by democratization and a growing awareness among top policymakers to align with global ideological changes. A former FD director general stated that Myanmar’s state forestry will move “from regulatory to participatory and from centralized to devolutionary and shared management” (LR 7). In the 2010s, local NGOs began advocating for human rights, linking the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with the idea that protecting forests should involve recognizing land rights and promoting local participation. These rights expanded to women’s rights to local participation (RWP 5). However, donor funding supported the expansion of the CF program, resulting in problems around CFUG sustainability and independence (RWP 4).

In response to concerns around CFUG’s sustainability and independence, forestry advisors expanded market rights for the locals (RWP 4). Policy suggestions were expanded to include financial and banking services, microcredit, insurance schemes, and export rights for CFUGs (RWP 6). These recommendations highlighted the reduction in state forestry responsibilities in the 1990s through neoliberal marketization and deregulation. The logic was that local responsibilities (individually or collectively) and marketization and freedom should replace state agencies’ responsibilities. These policy recommendations called for stricter RFs, granting CF rights in degraded and production forests currently under MSS and AAC control. These community rights and market forces challenged century-old scientific forest management and working plans (RWP 7).

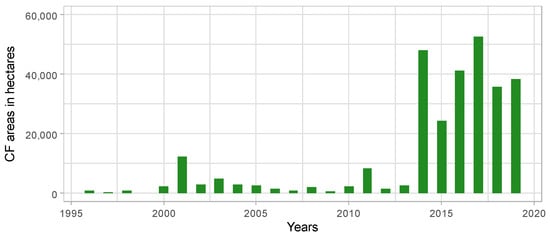

The FD reviewed CFI 1995, replacing it with CFI 2016 and, subsequently, CFI 2019. In CFI 2016, the FD added a section for community forest enterprises, rationalizing its importance for the sustainability of CFUGs. Moreover, economic activities in local forests were mandated under community forest-based enterprises. However, both enterprise terminologies were eventually consolidated into community forest-based enterprises in CFI 2019 (LR 11). Despite these changes, the FD continued to support traditional forest management principles under the guise of CFUG forestry management, raising questions about the effectiveness of the community-developed plans (RWP 6). The primary goal of neoliberal discursive strategy was to take the responsibility for the binary feature of ground management, where the FD took on the role of a regulator with diverse disciplines and procedures to ensure the state’s vision in the CF forests. Supported by the legitimacy of the NFMP and Forest Policy 1995, this hybridized CF program expanded from 785.49 hectares in 1996 to 289,161.65 hectares in 2019 (Figure 7) (LR 7). Myanmarian CF program shifted toward a neoliberal strategy that advocates market techniques and human rights by reducing and hollowing out the state’s responsibilities in forest management, timber marketing, and trading. However, the individual or collective responsibilities of the CF program with enhanced market rights also exposed the risk of illegal logging promoted by market motives and liberal creed in forestry [16,38]. The weak enforcement of regulations extends beyond illegal logging to land appropriation, where urban individuals exploit loopholes by registering as members of local Community Forestry User Groups (CFUGs). In doing so, they confiscate CF land, hold it, and resell it to wealthy urban investors—particularly in popular tourist areas such as Mandalay, Naypyidaw, and Pyin Oo Lwin.

Figure 7.

Establishment of community-based forest management in Myanmar (source: LR7).

5. Rise of the Facets of Market-Based Conservation

5.1. REDD+ Challenges: Inherited Political Issues and Fixing Deforestation with Marketization and Human Rights

Myanmar became a UN-REDD partner country in 2011, following the introduction of REDD+ during the democratic transition, which aimed to address people’s negative opinions on deforestation (RWP 8). Subsequently, the following three Technical Working Groups were formed: (1) Drivers and Strategy Development, (2) National Forest Monitoring System and Forest Reference Emission Levels/Reference Levels, and (3) Stakeholder Consultation and Safeguards. The program outlined six working components with an estimated budget of USD 23.3 million over four years to implement the Warsaw framework (RWP 9). Given the prioritized REDD+ discursive strategy as a technological fix, the Norwegian government provided USD 5.5 million in funding to initiate the operation of the UN-REDD National Programme in Myanmar (RWP 10).

Consultations with feedback and proposals were conducted in each state/region in 2017 and 2018. In 2019, Myanmar launched the draft National REDD+ Strategy, presenting it to 200 stakeholders at a two-day “National Validation Workshop” in September of that year (News 7). Furthermore, the FD considers the National REDD+ strategy as key to achieving sustainable forest management and biodiversity conservation in Myanmar (LR 7). A nationally endorsed Forest Reference Level was submitted to the UNFCCC for technical assessment in 2018, with REDD+ safeguards still underway (RWP 11). Meanwhile, a National Forestry Inventory design and sampling approach was developed in line with the existing forest inventory grid system and harmonized with land attributes for activity data and emission factor reporting (RWP 11 and 12).

The seven proposed National REDD+ Strategy policy actions and measures follow two unique logics. First, only the REDD+ initiative could align with the state forestry fortress conservation model. This result is evident even in the approach toward engaging Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) for cooperation on detecting illegal timber movement and establishing and managing PAs. Second, nearly all policy actions and measures were proposed to reduce state responsibilities, while essentializing non-state actors in forestry management. REED+ requires state-owned forests to be independently certified, encouraging secured tenure in CFs. Moreover, the REDD+ program urged the state to adopt the FPIC concept effectively in expanding contemporary PAs. In 2019, the FD and UN-REDD programs published a draft version of the FPIC guidelines to align with the Cancun safeguards (RWP 13).

UN-REED, Myanmar, was cognizant of the complex challenges in adapting the dual logics of “carbon trading” and “human rights.” The FD’s established management rationale of “reservation” conflicts with people’s rights (RWP 14). This finding was Myanmar’s most difficult issue in adhering to the Cancun safeguards of the REDD+ scheme. Furthermore, the latest UN-REDD report revealed significant difficulties facing the REDD+ model in Myanmar. The first was reaching a consensus among governmental and non-governmental institutions. The second was a two-century-old political engagement between the diverse categories of mountain people and EAOs, who controlled a significant portion of the forests. REDD+ in Myanmar encountered deeply rooted political challenges related to “ethnicity” and “statification,” concepts historically shaped during and after British colonial rule. Thus, adopting REDD+ faced the obstacles arising from the state’s fortress conservation and the unsettled political consensus among diverse categories of indigenous people, thereby elaborating multiple forms of rationales, techniques, and knowledge inside the program formulation [39].

5.2. Emergence of Timber Certification Schemes: Controlling Illegal Timber Trade Through Privately Controlled Timber Markets with Increased Third-Party Involvement

The European Union’s (EU) establishment of the European Timber Regulation (EUTR) in 2010 marked the introduction of the hegemony of third-party timber certification in tropical countries. The EU rationalized the EUTR as the responsible user of tropical hardwoods (LR 12). The EU’s Forest Law Enforcement, Governance, and Trade (FLEGT) model pressured tropical countries to comply with FPIC principles, local rights, private sector roles, third parties, and NGOs in establishing a responsible timber trade mechanism. Subsequently, the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF) expressed Myanmar’s interest in participating in the FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreement program to combat the illegal timber trade and improve the export of timber products (LR 13). Subsequently, the Interim Task Force—a collaborative effort involving representatives from ministries, private timber sectors, and civil organizations—was established in 2015 (LR 14).

MOECAF announced the establishment of a semi-independent organization, the Myanmar Forest Certification Committee (MFCC), in 2013. They embraced the neoliberal idea that third parties should handle the “timber certification” process. The goal was to establish the “Myanmar Forest Certification Scheme” and be recognized by international forest schemes (LR 15). The MFCC published the Myanmar Timber Legality Assurance System (MTLAS) and its audit forms, which were confirmed by the ministry in 2013 (RWP 15). In 2016, the FAO–EU FLEGT Program supported an MTLAS Gap Analysis to align current regulations with FLEGT requirements (RWP 16). The MFCC has issued three third-party timber certification licenses for local companies and one for an international company, taking over responsibilities from the FD and Myanma Timber Enterprises to ensure “transparency.” FLEGT Multi-Stakeholder Groups were formed in 2018 and expanded to all States and Divisions, establishing “interim measures” for the FLEGT program (RWP 16).

The EU’s program required more transparency in timber harvesting, concessions, and third-party accountability in forest certification, challenging Myanmar’s state forestry. The environment urged the state to accept the authority of CSOs and third parties in forest certification and to address human rights violations (News 8). Moreover, the EAOs substantially impacted the legality of Myanmar’s timber. Referring to article 6(1) (b), the EU highlighted the difficulty in assessing risks, citing issues of mixing potentially legally harvested timber with stockpiles of illegal timber. This assessment is the most challenging aspect in addressing Myanmar’s illegal logging due to the organized and diverse illegal timber supply networks (RWP 17). The issue extends beyond the often-highlighted armed conflicts and corruption to include a diverse range of market actors, from local farmers and intermediaries to privately controlled timber markets and storage facilities. Decades of neoliberal policies, coupled with internal conflict, have made Myanmar’s illegal supply chains uncontrollable. These challenges have made Myanmar incompatible with EU FLEGT regulations for the legal teak trade, substantially impacting the EU’s luxury yacht industry (News 9). Despite such limited progress, timber certification in Myanmar is in a transitional stage where the responsibilities of neoliberal market actors are absorbing those of FD and MTE. Therefore, third parties emerged as the responsible environmental subjects to ensure better accountability, transparency, and efficacy of local timber markets.

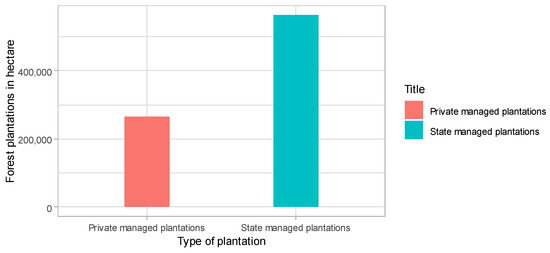

5.3. The Interplays of Fortress and Neoliberal Conservation in Private Plantation Industry

With the shift toward economic liberalization, the FD began permitting the establishment of private plantations. The aims were to accelerate plantation forestry, meet timber demand, increase forest cover, and enhance job opportunities. Private investors are granted 30-year leases. The new Forest Law (2018) further confirmed and legitimized the role of private actors in the forest plantation industry. The following figure illustrates the rapid development of private forest plantations in Myanmar. State-owned plantations were established solely by the FD. Between 1981 and 2019, the FD established over 0.5 million hectares of forest plantations. In contrast, although the private sector was a latecomer, it reached over 0.26 million hectares within 13 years (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Establishment of private sector forest plantations in Myanmar (source: LR7).

This deregulation effort aimed at enabling the marketing and export of timber from private plantations was also introduced, particularly evident in recent attempts to permit the export of teak logs. Following strong advocacy from the local timber merchants’ association, the NLD government even considered allowing the private sector to export teak logs harvested from private plantations.

6. Discussion

6.1. The Guided State: “Skeletal Forest Governance” in Myanmar

Global environmental politics largely influenced the development of Myanmar’s conservation schemes and those of other tropical countries after the 1990s [7,40]. These conservation discursive strategies infiltrated, mutated, and transformed the existing fortress conservation of state forestry conservation with financial support, establishing new conservation governance mechanisms. Myanmarian state forestry and fortress conservation was founded on German principles of sustained yields during the colonial 1850s [2]. Global environmental politics reshaped new pillars, such as marketization, deregulation, local participation, and human rights. However, prioritizing neoliberal values in conservation may be questionable, particularly concerning their universal application in specific geographies and political contexts [22,41]. Furthermore, internationalism often fails to provide equitable solutions for developing countries [42].

This phenomenon has led to the development of skeletal forest governance in Myanmar. Problem-driven reforms with a regional focus are critical for developing countries [43]. Contemporary efforts have focused on localized issues and geographical problems in Myanmar. However, this new skeletal forest governance was underpinned by a convergence of foundational pillars, each emerging from distinct discursive strategies, including colonial science-based forest management, community-led conservation approaches, collective ideologies, neoliberal marketization, and the discourse of individual rights. Additionally, Myanmar’s emerging skeletal forest governance addresses localized and context-specific issues through the lens of the three dominant conservation ideologies, effectively positioning local realities as secondary to the ideologically driven foundational pillars. This hierarchical structuring has contributed to persistent complications, including the proliferation of illegal logging despite official logging restrictions, and ongoing tensions between forest reservation targets and the land rights of local communities.

In contrast, the root causes of Myanmar’s illegal logging and timber trade were market liberalization and diverse local timber supply chains. These issues were only exacerbated by market pressures from neighboring countries and the internal timber supply deficit, as shown earlier [2,16]. Moreover, illegal logging is a localized issue leading to forest degradation, with the variegated extraction of economic timber species for diverse economic reasons [44]. State forestry’s absolute ownership of forests is the primary cause of land grabbing and the insecure tenure of locals [45]. Development projects, agricultural concessions, and expansions are significant causes of deforestation [46]. Forest conservation models must map these local problems and develop optimal solutions without undermining transformative potential. A notable example is the emergence of a problem-based strategy in the (self-funded) reforestation program (MRRP) designed to offset the supply deficit from natural forests. This strategy aligns with a neoliberal market economy approach, suggesting the advancement of the MRRP toward a corporatized, cost–benefit-based timber supply mechanism, with future yield calculations to sustain local timber markets.

Moreover, owing to the interplays between the NC and fortress conservation models of this skeletal forest governance, the double process of land accumulation has occurred in Myanmar, namely, primitive land accumulation and land accumulation by dispossession. First, Marx stated: “So-called ‘primitive accumulation’, therefore, is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production” [47] (p. 875). Under the discursive strategy of protectionist and sustainable logics, the state’s fortress conservation effectively separated local people from forested lands. This decision created a form of primitive accumulation of land through the designation of “reserved forests” by the state agency (FD). This phenomenon aligns with Marx’s emphasis on state apparatuses and power [33,48]. Second, under the newer neoliberal discursive strategy emphasizing marketization and the enhanced role of the private sector, the rationale became that private actors would manage economic plantations. This decision resulted in the dispossession of local communities from nearby forested lands in favor of private interests. Thousands of private actors—many of whom were not local—gained control over land management, operating under the Forest Department’s (FD) supervision. Third, under the same neoliberal strategy, large companies and wealthy individuals acquired vast tracts of land for plantation industries. This thought process aligns with Harvey’s [33] concept of “accumulation by dispossession,” whereby land is concentrated in the hands of the elites from different regions (mostly from urban cities like Yangon, Naypyidaw, and Mandalay) who control these lands from their headquarters, further marginalizing local communities that lose their cultural and social status and become plantation workers in the private industry in the private plantation industry. Thus, this phenomenon of land transfer, though often violent and far from peaceful, as Marx noted, resulted from shifts in discursive strategies in forest conservation and state mediation upon these discursive shifts [48].

6.2. The Interacting Trilogy of Forest Conservation

The arts of government in state forestry use scientific standard procedures aligned with top-down regulations [2,3]. In the context of participatory programs (CF in Myanmar), they seek to engage with disciplined communities via state forestry. However, neoliberal market orders and human rights movements have transformed this approach, resulting in a hybrid model [10,12]. This change led to the creation of the CFUGs as environmental entrepreneurs driven by neoliberal marketization and deregulation [49]. Market- and rights-based approaches (REDD+ and Timber Certification Schemes) were central to neoliberalism’s hollowing out of the state’s responsibilities. All regulatory procedures and discursive platforms (state and non-state) had been transformed through the neoliberal tactics of marketization and deregulation, increasing private and non-state actors’ roles and human rights [50]. These procedural changes resulted in the operational responsibilities of state forestry being transferred to non-state actors while the state became, in Friedman’s [23] words, “the umpire of forest conservation” [11]. Thus, a trio of forest conservation has emerged in Myanmar, reflecting Fletcher’s [39] concept of “multiple governmentalities”, where neoliberal influences have become prominent in forestry reforms. Depending on the knowledge and resulting techniques of each discursive strategy, Myanmar’s state forestry transformed from the expansion of forest reservations by thousands of kilometers to a decentralized and deregulated, community-based forest management system, with over six hundred thousand acres co-managed by the Forest Department and local communities.

Additionally, the neoliberal discursive strategy of enhancing the role of the private sector endorsed increased land control by non-forest-dependent communities, highlighting the phenomenon that Harvey termed “accumulation by dispossession” [33,47,48]. Even though neoliberal land dispossession has occurred at the local level, marginalizing communities from forest governance and facilitating private access to forested lands; the formal recognition of local control has simultaneously gained traction. This paradoxical development reflects the contested and negotiated nature of forest governance in Myanmar, where state and non-state actors navigate between market-driven reforms and community-based approaches. Concurrently, although NC and CBC advance differing agendas, both frameworks challenge the centralized and exclusionary logic of fortress conservation by promoting more decentralized, participatory, and market-oriented approaches to forest governance.

Due to neoliberal market liberalization after the 1990s, Myanmar ranked among the top ten most deforested countries in the world [51,52]. The neoliberalization of Myanmar’s timber industry led to logging beyond the limits set by the Myanma Selection System’s annual allowable cut, resulting in a sharp decline in natural forest timber supply. From 2019 onward, the establishment of community forest-based enterprises (CFEs) and the deregulation of timber extraction rights enabled CFEs to officially produce wood products [16]. Additionally, private plantations began supplying timber through thinning, although most trees remain immature. However, the volume of wood products recently produced by CFEs and private plantations remains small, and the relevant data are largely inaccessible. A major challenge for the timber industry is the potential risk of illegal timber being mixed with legal timber within local distribution channels, as well as in storage and processing facilities (RWP 17).

Forest conservation in Myanmar is caught in a triangular dynamic, as follows: (1) fortress-style, protectionist conservation; (2) neoliberal, market- and rights-based approaches; and (3) community-based models. We propose moving beyond rigid governance categories toward context-sensitive conservation, effectively integrating elements from each model as needed. For instance, individual agroforestry and forest enterprises may suit forest-encroaching communities [29], while collective management works better for shared watershed forests in mountainous areas [RWP 6], blurring the line between neoliberal and community-based approaches. In the Bago mountain range, degraded by overlogging, a fortress model may still be necessary but should engage locals reliant on non-timber resources. In contrast, northern highland forests with snowcapped mountains, vital to Indigenous livelihoods, should be community-led, with carefully designed ecotourism models that prioritize local—not urban/private—actors. Ultimately, effective forest governance in Myanmar demands flexible, locally attuned policy frameworks, supported by a clear and inclusive vision from the state.

7. Conclusions

We have shown how neoliberal global environmental politics shaped Myanmar’s complex forest conservation landscape [19]. Using integrative methods from Foucauldian genealogy, governmentality, and neoliberal political philosophy, we examined the transformation of the arts of government. We performed a critical institutional study of transformative power in forestry. The neoliberal engine of the entrepreneurial agent exercises power through freedom to shape the politics of forest conservation [27]. Notably, Myanmarian scientific forestry appeals more to natural conditions, whereas the neoliberal and CBC models appeal more to the rights and freedom of individuals or groups. Furthermore, Myanmar’s “statification”—bringing public issues under state control—encompassed all forest conservation discourses but gradually shifted the state’s ground management responsibilities to the locals, third parties, and private sectors under the influence of “neoliberal governmentality” [18].

Understanding the Myanmarian forest conservation trilogy (fortress, participatory, and neoliberal) reveals these models’ overlapping but contradictory priorities. Future policy remedies should consider the incompatibilities of the founding pillars of each discourse on forest conservation with local conditions rather than focusing on these models’ constituted effects and negative impacts. Moreover, we recommend avoiding universalizing any arguments (neoliberal or others) in forest conservation and instead focusing on shared goals for the forests and the people of each unique location. In Myanmar and other developing countries with similar contexts, we recommend establishing policy pillars with regional problem-based approaches instead of direct ideological actions. In doing so, we refer to context-based, problem-driven policies that prioritize local conditions, while effectively integrating global forest conservation ideas that are best suited to each specific local context.

The emergence of the trilogy of forest governance in Myanmar highlights the necessity of critically examining the foundational logics underpinning current forest conservation approaches. Future forest policy frameworks should prioritize effectively integrating this tripartite governance structure, while simultaneously striving to mitigate adverse impacts on forest commons, forestry market systems, local communities, and broader forest and environmental conditions. This study is limited to state transformations and should be followed by regional and case-based empirical analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.P.; methodology, W.M.P.; formal analysis, W.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.P.; writing—review and editing, P.P.H., M.O. and T.F.; visualization, W.M.P.; supervision, M.O. and T.F.; project administration, T.F.; funding acquisition, T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP21H03709, JP23K21808, and JST SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2136.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments. Their feedback greatly contributed to the improvement of the manuscript during the revision process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Newspaper Sources

| News 1 | Naw Noreen, Loggers declare one-year moratorium, Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), 6 July 2016. https://english.dvb.no/loggers-declare-one-year-moratorium/ (accessed 10 June 2022) |

| News 2 | Justine E. Hausheer and Timothy Boucher, Illegal Logging & Energy Shortages Pressure Myanmar’s Forests, The Nature Conservancy, 9 July 2018. https://blog.nature.org/2018/07/09/illegal-logging-energy-shortages-pressure-myanmars-forests/ (accessed 10 June 2022) |

| News 3 | Eleven Media Group (EMG), 21 December 2020, https://news-eleven.com/article/200362 (Burmese version) (accessed 24 October 2022) |

| News 4 | Fishbein, E., Communities Clash with Conservation Efforts in Northern Myanmar’s Hkakaborazi Region, MONGABAY, 28 April 2020. https://rainforestjournalismfund.org/stories/communities-clash-conservation-efforts-northern-myanmars-hkakaborazi-region (accessed 11 June 2022) |

| News 5 | UNESCO, Hkakabo Razi Landscape, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5871/ (accessed 11 June 2022) |

| News 6 | Eleven Media Group, The local people sued by the Forest Department and the Napyidaw Municipal Committee will submit a petition to the president (Burmese version), 12 January 2015, https://news-eleven.com/article/257998 (accessed 11 June 2022) |

| News 7 | Liu, L., WORKING TOGETHER TO SAVE MYANMAR’S FORESTS, UN REDD Program, (https://www.un-redd.org/multi-media-stories/working-together-save-myanmars-forests/) (accessed 21 December 2023) |

| News 8 | Challenges Await as Burma is Vetted for EU Timber Trading Partnership, The Irrawaddy, November 22, 2016. (https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/challenges-await-as-burma-is-vetted-for-eu-timber-trading-partnership.html (accessed 16 May 2024)) |

| News 9 | Ratcliffe, J., Tainted Teak: The yachting industry’s shift to sustainable decking, Super Yacht Times 6 January 2024. https://www.superyachttimes.com/yacht-news/sustainable-yacht-decking (accessed 16 May 2024) |

Appendix B. Reports and Working Papers from NGOs, Newspaper Sources

| RWP 1 | Policy Advocacy on Empowering Local Communities for Effective Resource Protection and Environmental Security, ALARM (Myanmar) (Burmese version). https://alarmmyanmar.org/pdf/CSO%20Position%20Paper%20for%20Effective%20Resource%20Protection.pdf (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 2 | UNESCO, Hkakabo Razi Landscape, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5871/ (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 3 | https://myanmar.wcs.org (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 4 | Tint, K., Springate-Baginski, O., and Gyi, M.K.K. (2011) Community forestry in Myanmar: progress and potential. |

| RWP 5 | Khin Moe Kyi, Khin Thiri, Kerry Woodward, and Jeffrey Williamson, Enhancing human rights through community forestry: a case from Myanmar, Stories, RECOFTC, 10 December 2017. https://www.recoftc.org/stories/enhancing-human-rights-through-community-forestry-case-myanmar (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 6 | Tint, K, Springate-Baginski, O., Macqueen, D.J., and Mehm Ko Gyi (2014). Unleashing the potential of community forest enterprises in Myanmar. Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative (ECCDI), University of East Anglia (UEA), and International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, UK. |

| RWP 7 | Cho, B., Naing, A. K., Sapkota, M. L., Than, M. M., Gritten, D., Stephen, P., Lewin, A., and Tint Lwin Taung, L. T., 2017. Stabilizing and rebuilding Myanmar’s working forests: Multiple stakeholders and multiple choices. The Nature Conservancy and RECOFTC. |

| RWP 8 | UN-REDD Program (Myanmar), National Strategy, available at https://www.un-redd.org/partner-countries/asia-pacific/myanmar (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 9 | Myanmar REDD+ Readiness Roadmap, UN-REDD Program Myanmar, July 2013. |

| RWP 10 | UN-REDD Program, Support to the Implementation of Myanmar’s REDD+ Readiness Roadmap, October 2013, https://www.un-redd.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Myanmar%20Funding%20proposal%2012%20Nov.pdf (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 11 | UN-REDD Program Myanmar, National Strategy (Draft). |

| RWP 12 | UN-REDD Program Myanmar, Myanmar REDD+ Safeguard Roadmaps, September 2017. |

| RWP 13 | UN-REDD Program Myanmar, Guidelines for an approach to ensure FPIC in the implementation of Myanmar’s National REDD+ Strategy and other initiatives affecting forests, December 2019. |

| RWP 14 | UN-REDD Program Myanmar, First summary of information on how safeguards for REDD+ are addressed and respected in Myanmar, December 2019, https://redd.unfccc.int/media/myanmar_1st_summary_of_information-_eng_final_29_june_2020.pdf (accessed 16 May 2024) |

| RWP 15 | MFCC, MTLAS knowledge information sharing, 30 August 2018. |

| RWP 16 | MFCC, MTLAS GAP Analysis, Final Report, 2017. |

| RWP 17 | Conclusions of the Competent Authorities for the implementation of the European Timber Regulation (EUTR) on the application of Articles 4(2) and 6 of the EUTR to timber imports from Myanmar, Member States (EG) Meeting, 9 December 2020. |

Appendix C. Laws and Regulations

| Label | Description | Data Source |

| LR 1 | Chapter 2, Article 18 (a), The constitution of the Socialist Republic of Burma (1974), 3 January 1974 | Myanmar Law Library and Burma Library |

| LR 2 | The State Law and Order Restoration Council, Forest Law, Law No. 8/92, 3 November 1992. Ministry of Forestry, Myanmar Ministry of Forestry, Forest Rules 1995, 1 December 1995. | Myanmar Law Library and Burma Library |

| LR 3 | Seven instructions from the senior general in the ‘Ranger Manual’, February 2003, Burmese version. | Forest Department (FD) (https://forestdepartment.gov.mm/law (Accessed 23 May 2023)) |

| LR 4 | Myanmar Forest Policy 1995. | FD |

| LR 5 | Chapter 4, Protection of Wildlife and Protected Areas Law, The State Law and Order Restoration Council, Law No. 6/94, 8 June 1994. | FD, Myanmar Law Library and Burma Library |

| LR 6 | Ministry of Forestry, National Forest Master Plan, 30 June 2001. | FD |

| LR 7 | Forest Department, Forestry in Myanmar 2019–2020, 2020, pp. 21. | Burma Library and FD |

| LR 8 | Standard Operating Procedures for Demarcation of Reserved and Protected Public Forests and Protected Areas. Forest Department, February 2016 (Burmese version). | FD |

| LR 9 | Forest Department, Myanmar Reforestation and Rehabilitation Program, 2017. | FD |

| LR 10 | Forest Department, Notification 1/95, Community Forestry Instructions, 1 December 1995. | FD |

| LR 11 | Ministry of natural resources and environmental conservation, notification 84/2016, Community Forestry Instructions, 16 August 2016, and notification 69/2019, Community Forestry Instructions, 8 May 2019. | FD |

| LR 12 | Regulation (EU) No 995/2010, Laying down the obligations of operators who place timber and timber products on The market, the European Parliament, and the Council of the European Union, 20 October 2010. | EU |

| LR 13 | Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Letter No. (1/EU—FLEGT (6459/2013), 26 November 2013. | FD |

| LR 14 | Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Letter No. 3(1)/01(b)/(2049/2015), 21 August 2015. | FD |

| LR 15 | Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Announcement No. 24/2013, 17 July 2013. | FD |

References

- Barton, G.A. Empire Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R.L. The Political Ecology of Forestry in Burma 1824–1994; University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.P.; Paing, W.M.; Ota, M.; Fujiwara, T. The evolution of land governance in Myanmar: A historical analysis of the people-land nexus in the Konbaung dynasty and British colonial eras. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 172, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htun, N.Z.; Mizoue, N.; Kajisa, T. Deforestation and forest degradation as measures of Popa Mountain Park (Myanmar) effectiveness. Environ. Conserv. 2009, 36, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15188–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Neoliberal environmentality: Towards a poststructuralist political ecology of the conservation debate. Conserv. Soc. 2010, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Failing Forward: The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Conservation; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Wildburger, C.; Grima, N.; Fisher, B. International Forest Governance: A Critical Review of Trends, Drawbacks, and New Approaches; IUFRO World Series; International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO): Vienna, Austria, 2024; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.; Buck, A.; Katila, P. Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; IUFRO World Series; International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO): Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J.M. Community forestry engagement with market forces: A comparative perspective from Bhutan and Montana. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, H.J. The role of government in operationalising markets for REDD+ in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 86, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Devolution in the Woods: Community Forestry as hybrid Neoliberalism. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2005, 37, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.D. Payments for environmental services as neoliberal market-based forest conservation in Vietnam: Panacea or problem? Geoforum 2012, 43, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, G.W.; Sutherland, W.J.; Aguirre, D.; Baird, M.; Bowman, V.; Brunner, J.; Connette, G.M.; Cosier, M.; Dapice, D.; De Alban, J.D.T.; et al. Political transition and emergent forest-conservation issues in Myanmar. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, K.M.; Naimark, J. Conservation as counterinsurgency: A case of ceasefire in a rebel forest in southeast Myanmar. Polit. Geogr. 2020, 83, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paing, W.M.; Han, P.P.; Ota, M.; Fujiwara, T. The state-private hybrid forest policy in Myanmar: The impact of neoliberalism on the forestry sector after the 1990s. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 148, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Security, Territory and Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1976–1977; Picador: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France 1977–1978; Picador: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulou, E.; Chatzimentor, A.; Maestre-Andrés, S.; Requena-i-Mora, M.; Pizarro, A.; Bormpoudakis, D. Reviewing 15 years of research on neoliberal conservation: Towards a decolonial, interdisciplinary, intersectional and community-engaged research agenda. Geoforum 2021, 124, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. The Moral Law: The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. Liberalism and the Limits of Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F. The Road to Serfdom; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F. The Constitution of Liberty: The Definitive Edition; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karen, A. Why Exchange Values are Not Environmental Values: Explaining the Problem with Neoliberal Conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 16, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni, L. Governing through disorder: Neoliberal environmental governance and social theory. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 21, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, D. Discourse as ideology: Neoliberalism and the limits of international forest policy. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.P.; Paing, W.M.; Ota, M.; Fujiwara, T. State’s Techniques and Local Communities’ Strategies in Land Contestations over Agro-Based Community Forests in Myanmar. Land 2025, 14, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, R. The Nature of Capital: Marx After Foucault; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leipold, S.; Feindt, P.H.; Winkel, G.; Keller, R. Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 21, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. A Companion to Marx’s Capital; Verso: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Orders of discourse. Soc. Sci. Inform. 1971, 10, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, H.R. Highlights of one hundred years of forestry in Burma. Emp. For. Rev. 1958, 37, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Khai, T.C.; Mizoue, N.; Ota, T. Harvesting intensity and disturbance to residual trees and ground under Myanmar selection system: Comparison of four sites. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springate-Baginski, O. Community Forestry in Myanmar: Centralised decentralisation under conflictual authoritarianism—Not yet rights-based resource federalism. In Routledge Handbook of Community Forestry; Bulkan, J., Palmer, J., Larson, A.M., Hobley, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. Environmentality unbound: Multiple governmentalities in environmental politics. Geoforum 2017, 85, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidone, F. Investigating Forest Governance through Environmental Discourses: An Amazonian case study. J. Sustain. For. 2021, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Cosmopolitanism and the Geography of Freedom; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ciplet, D.; Roberts, J.T. Climate change and the transition to neoliberal environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 46, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M. The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development: Changing Rules for Realistic Solutions; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saung, T.; Khai, T.C.; Mizoue, N. Condition of illegally logged stands following high-frequency legal logging in Bago Yoma, Myanmar. Forests 2021, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehringer, J.G.; Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.; Thein, T.T. The cash crop boom in southern Myanmar: Tracing land use regime shifts through participatory mapping. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.L.; Prescott, G.W.; de Alban, J.D.T. Untangling the proximate causes and underlying drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Myanmar. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, K. Capital: Volume 1–3: A Critique of Political Economy; Penguin Classics: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wolford, W.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; White, B. Governing global land deals: The role of the state in the rush for land. Dev. Change 2013, 44, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, J.C. Assembling participatory Tambopata: Environmentality entrepreneurs and the political economy of nature. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.L.; Krott, M.; Sayadyan, H. The World Bank improving environmental and natural resource policies: Power, deregulation, and privatization in (post-Soviet) Armenia. World Dev. 2017, 92, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).