Abstract

Historically protected by cultural traditions, sacred forests are now increasingly threatened by anthropogenic pressures, particularly in West Africa, where natural areas and wildlife populations have dwindled as human populations have increased exponentially. Residents in the vicinity of sacred forests play critical roles in conservation success or failure, but few studies have investigated their views. We surveyed 281 residents representing ~100% of households surrounding the sacred forest of Nakpadjoak, a 50-hectare remnant of Sudan-Guinea woodland savanna in northern Togo that is now surrounded by human-dominated landscapes. The majority of residents believe that the sacred forest should be protected (92%) and that access to the forest should be prohibited (55%). Most residents own livestock (93%) and reported that the forest has become a pasture for domestic animals (70%) while wildlife populations have declined (79%). Two-thirds of residents (64%) reported that the forest has changed due to wood cutting, a practice that occurs despite being banned. Most (96%) residents use wood as their primary source of domestic energy, but 90% would switch to alternative fuels, such as natural gas, if available. Unfortunately, despite residents’ desire to protect the forest and external funding for its protection and restoration, Nakpadjoak forest has become increasingly degraded due to ongoing exploitation and conflicts of interest surrounding its use. We recommend bolstering local prohibitions on sacred forest exploitation as well as government interventions such as subsidizing natural gas as an alternative to wood fuel to support the conservation of this and other protected areas in the region, which may otherwise be destroyed.

1. Introduction

Overexploitation by people is one of the primary threats to natural areas and wildlife populations today [1,2]. Global population numbers are projected to increase from 8 billion in 2022 to 9.7 billion by 2050, disproportionately impacting natural areas and wildlife in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the fastest growing human population in the world [3]. Human activities are intensifying across Africa, especially West Africa, where human population densities are highest [4]. Natural areas and wildlife populations are increasingly being destroyed as lands are converted for agriculture [4,5,6], the dominant economic activity in West Africa [7], to support expanding human populations. Wood fuel is the most significant energy source for residents of sub-Saharan Africa, driving 80% of the total wood consumption in the region, and wood fuel consumption significantly accelerates forest degradation [8]. Wood and charcoal are typically easily available, either for free or at low costs to consumers, whereas other fuel sources may be considered too expensive or difficult to access [9]. Historically, relatively low numbers of people harvesting wood from vast natural areas may have been sustainable, but recent unprecedented population growth has led to unsustainable conversion and destruction of natural areas, constituting a major threat to ecosystems and wildlife across West Africa [10].

Like many other African countries, Togo faces significant environmental challenges, including land degradation, deforestation, and biodiversity loss [11]. During Togo’s time as a German protectorate from 1884 to 1914 and a French colony from 1919 to 1960, tree plantations expanded, a trend that continued for several decades after Togo’s independence in 1960 [12]. However, between 1985 and 2020, Togo lost over half of its forest cover—approximately 1,500,000 hectares—to expanding agriculture and other land conversion associated with the rapid expansion and growth of Togo’s population [13]. Although Togo officially has a total of 83 protected areas covering 14% of the country, political and ethnic conflicts amidst a burgeoning population have led to the partial or total destruction of much of this natural heritage in recent decades [14,15,16]. In northern Togo, for example, many wildlife populations have been poached to extinction in Fosse aux Lions and Kéran National Parks, where human activities have destroyed almost all the native vegetation [17]. Remaining protected areas in Togo face significant ongoing threats from human activities including poaching, logging, agriculture, charcoal production, and cattle grazing, as well as the introduction of invasive species that inhibit natural forest regeneration [17,18,19,20].

Complementing larger protected areas, sacred forests and other culturally significant sites are found throughout the world, including Togo and elsewhere in West Africa [12,21,22]. Sacred sites commonly hold significant cultural, spiritual, or religious importance to local communities, serving as places for the practice of traditions and the preservation of heritage [12,23,24,25]. Some sacred sites are credited by local communities as influencing natural events, such as rainfall [26,27]. Though usually small and often isolated, sacred sites can also function as refuges for threatened or endangered species, demonstrating higher ecological value and less degradation than other comparable sites [12,27,28,29]. Grazing livestock, hunting, and cutting wood are often forbidden to protect sacred sites’ ecological integrity [25,30]. However, economic pressures [31] or eroding traditions [32,33] may lead people to break cultural norms that previously protected sacred sites.

Cultural traditions in Togo, as elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, have been eroding in the context of political changes, globalization, and rapid population growth [12,27]. The abandonment of traditional beliefs may have significant negative consequences for the protection of sacred sites, as local communities may value them less, increasing their vulnerability to degradation and destruction [24,34]. Effective ways to uphold, encourage, and build on traditional conservation practices are urgently needed, and community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) may provide a means of building local support for conservation [35,36], including in relation to sacred sites. Through CBNRM, communities establish regulations and rules based on their own goals, which may receive support from external entities such as national governments and/or non-governmental organizations [35,36]. Although CBRNM has been the subject of many publications, few studies have explored the conservation views of residents living near sacred forests as traditional cultural norms in many countries are undergoing rapid change [22].

Residents near sacred forests are crucial partners for data collection, public engagement, and collaborative conservation projects. Their views are essential to understanding community involvement in natural resource use and/or conservation enforcement mechanisms, particularly as governance effectiveness and control of corruption has been shown to mitigate forest degradation in sub-Saharan Africa [8]. Here, we investigated perceptions of residents surrounding a sacred forest in northern Togo that has come under tremendous pressure due to anthropogenic overexploitation. Tree cutting for household fuel is a major driver of deforestation in sub-Saharan Africa [37], but nevertheless continues in part because residents often perceive a lack of viable alternatives to securing household energy, so this subject was a particular focus of our research. Our objectives included the following: (1) to evaluate local perspectives on the current and future role of the sacred forest, (2) to identify resident views on policy and management strategies for the sacred forest, and (3) to assess local willingness and capacity to use alternatives to wood as a primary household energy source, a strategy that has important implications for trees and forests in sub-Saharan Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

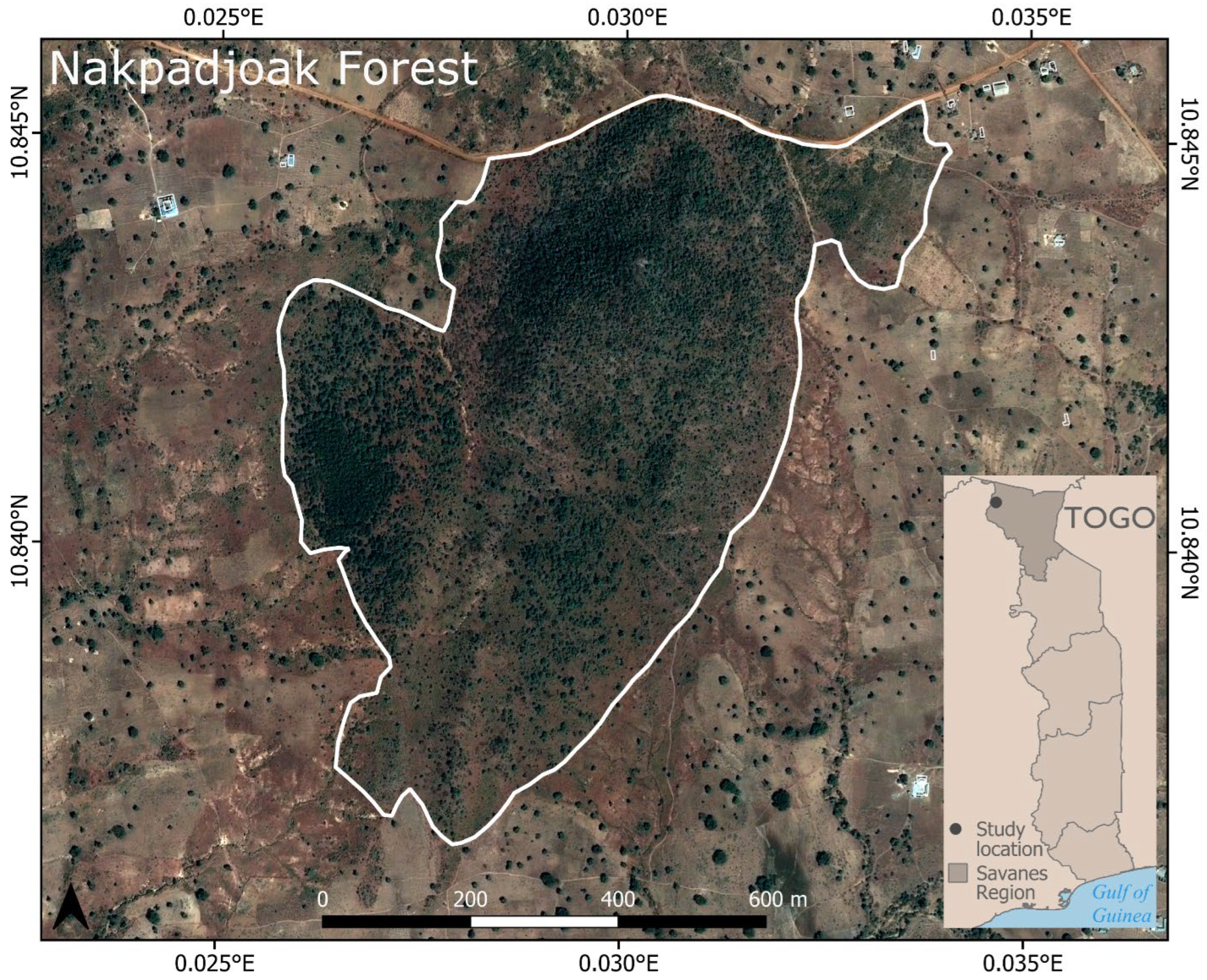

Our study area included households surrounding the 50-ha forest of Nakpadjoak (10.841° N, 0.029° E; Figure 1) in northern Togo, West Africa, which residents in the village of Tami have traditionally protected as a sacred site. Nakpadjoak forest is located within the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome, which extends from Senegal to Eritrea, and historically consisted primarily of native grasslands, scattered trees, and shrubs. However, much of this once extensive savanna ecosystem has been degraded and destroyed as a result of increasing human populations and exploitation of natural resources [10,38], including across Togo [13] and around this sacred forest [39]. Agricultural fields surround the forest, highlighting the dominance of farming as the primary land use. Houses, buildings, and other human-dominated spaces occupy most non-cultivated land, leaving little remaining native woodland savanna habitat, with the exception of the sacred forest, which is bordered by a road on its northern perimeter and a footpath at its eastern limit (Figure 1). Togo annually experiences a wet season from May to October and a dry season from November to April, with an annual rainfall ranging from 900 to 1100 mm. The forest is located 1.7 km from Tami’s center and marketplace and ranges from 269 to 321 m in elevation ( = 287.8 m ± 1.1 SE). Dominant tree species in the area include Parkia biglobosa and Butyrospermum parkii, while the sacred forest includes Sudanian forest species such as Anogeissus leiocarpus, Piliostigma reticulatum, and Ziziphus mauritiaca [39].

Figure 1.

The sacred forest of Nakpadjoak (outlined in white) in the village of Tami, northern Togo, West Africa. Map by Brandon Franta using QGIS version 3.36.3 [40] and satellite imagery taken on 29 November 2020, ©2025 Airbus, acquired via Apollo Mapping.

2.2. Data Collection

Prior to conducting surveys, we visited the mayor of the prefecture of Tône 3 and the canton chief of Tami to discuss our survey objectives and request permission to conduct this study, which was granted. After the local community was informed of our survey objectives by the canton chief, we conducted semi-structured interviews by walking from one household to the next nearest household around the sacred forest between May and July 2023. Interviews lasted 8–20 min and were conducted in the local language, Moba, and/or Togo’s official language, French. Before each interview, we explained our objectives and asked participants for their permission to interview them, reminding them that participation was voluntary and that they could skip any question or stop the interview at any time. Prior to interviews, participants were also informed that their responses would remain anonymous to protect their privacy, and we did not record participant names or household locations for this reason [41]. Our survey consisted of 45 questions covering three sections: demographics, information relative to the sacred forest, and household energy sources. We used a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions, with most open-ended questions offering hybrid answer options. The hybrid answers helped guide participants, allowing them to express themselves while also providing a structure for quantitative analyses.

2.3. Data Analyses

We calculated the total number and percentage of responses to each question and used a logistic regression to separately identify explanatory variables influencing respondents’ (1) views on forest access, (2) perceptions of change in the forest, and (3) ability to afford the cost of the main local alternative fuel, which is natural gas. At the time of our study, filling a tank of natural gas cost the equivalent of approximately USD 7.23 in local currency. We used the glm package in R version 4.2.2 [42] with a binomial distribution and logit link function, setting the threshold of significance at p < 0.05. During model selection, we removed terms that did not explain variation for the respective response variable. We then selected the model with the lowest corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) and highest AICc weight to address each question. Finally, we developed three different models, each designed to answer a specific question. We analyzed respondents’ views on forest access (binomial) using age and ownership of domestic cattle (binomial) as explanatory variables. We assessed perceived change in the forest (binomial) with sex and ownership of domestic cattle (binomial) as explanatory variables. Finally, we asked respondents’ assessments of their financial ability to refill a natural gas tank; such gas tanks are available in the nearby city of Dapaong, ~25 km by road from Tami. Resident responses were evaluated with respect to their sex, age, and household distance to the forest (estimated by surveyors; categorical) as predictor variables.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Responses

The survey had a 100% response rate (281 surveys completed), with 63% female and 37% male respondents (women were more likely than men to be home during the day, when we conducted interviews). Participants ranged in age from 19 to 90 years old ( = 42 ± 15 SD). The vast majority (99%) were members of Togo’s Moba ethnic group; one respondent identified as Mossi, the largest ethnic group of Burkina Faso, Togo’s neighbor to the north. The majority (71%) of respondents had never attended school or received any formal education, while 15% had attended primary school (ages 6–11), 11% had attended middle school (ages 11–15), and 3% had attended secondary school (ages 15–18). Most participants (81%) lived in households with more than five people. The vast majority of residents (93%) owned livestock, with nearly two-thirds (65%) owning cattle, and the remainder owning one or more sheep, goats, donkeys, or horses.

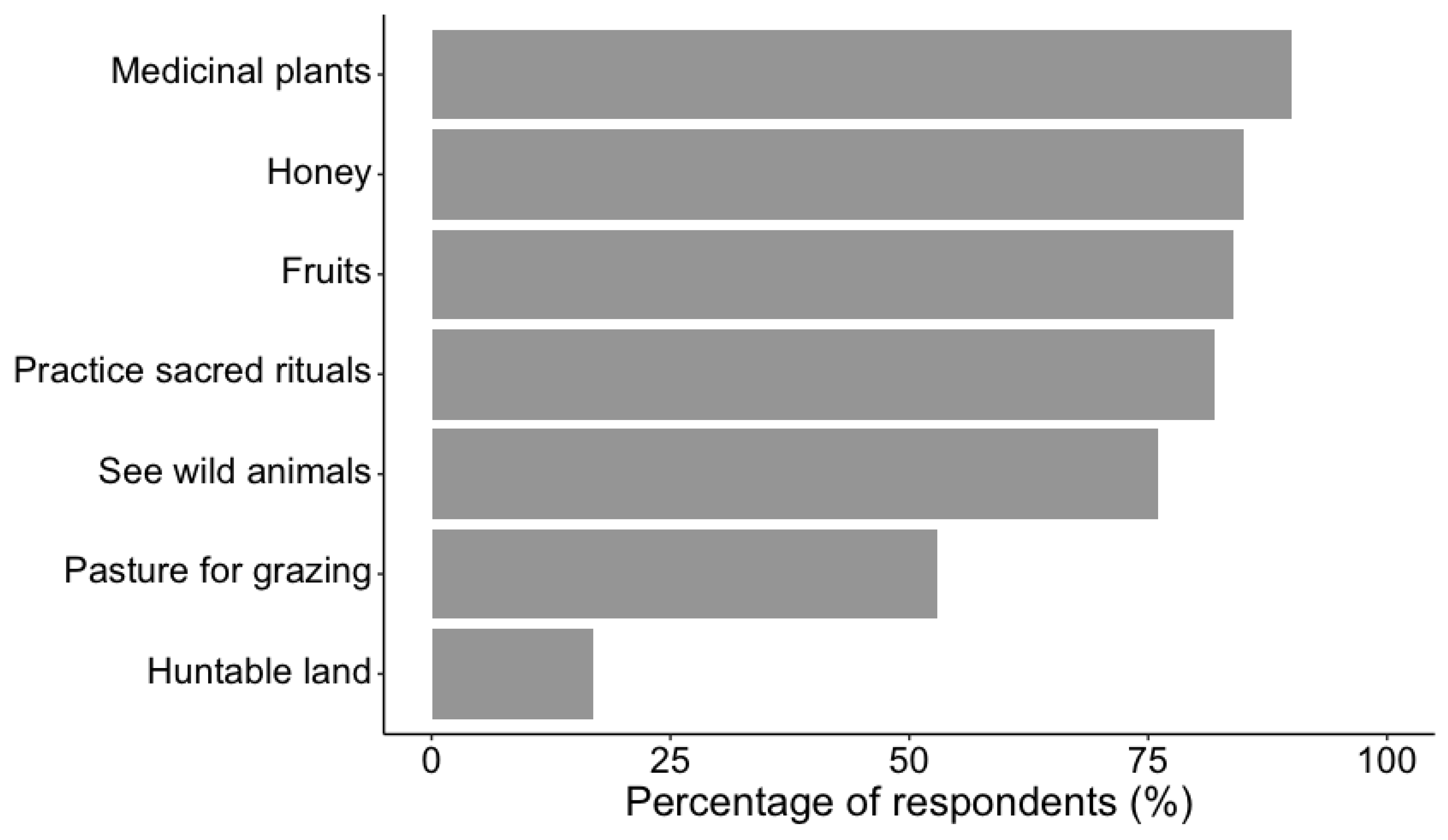

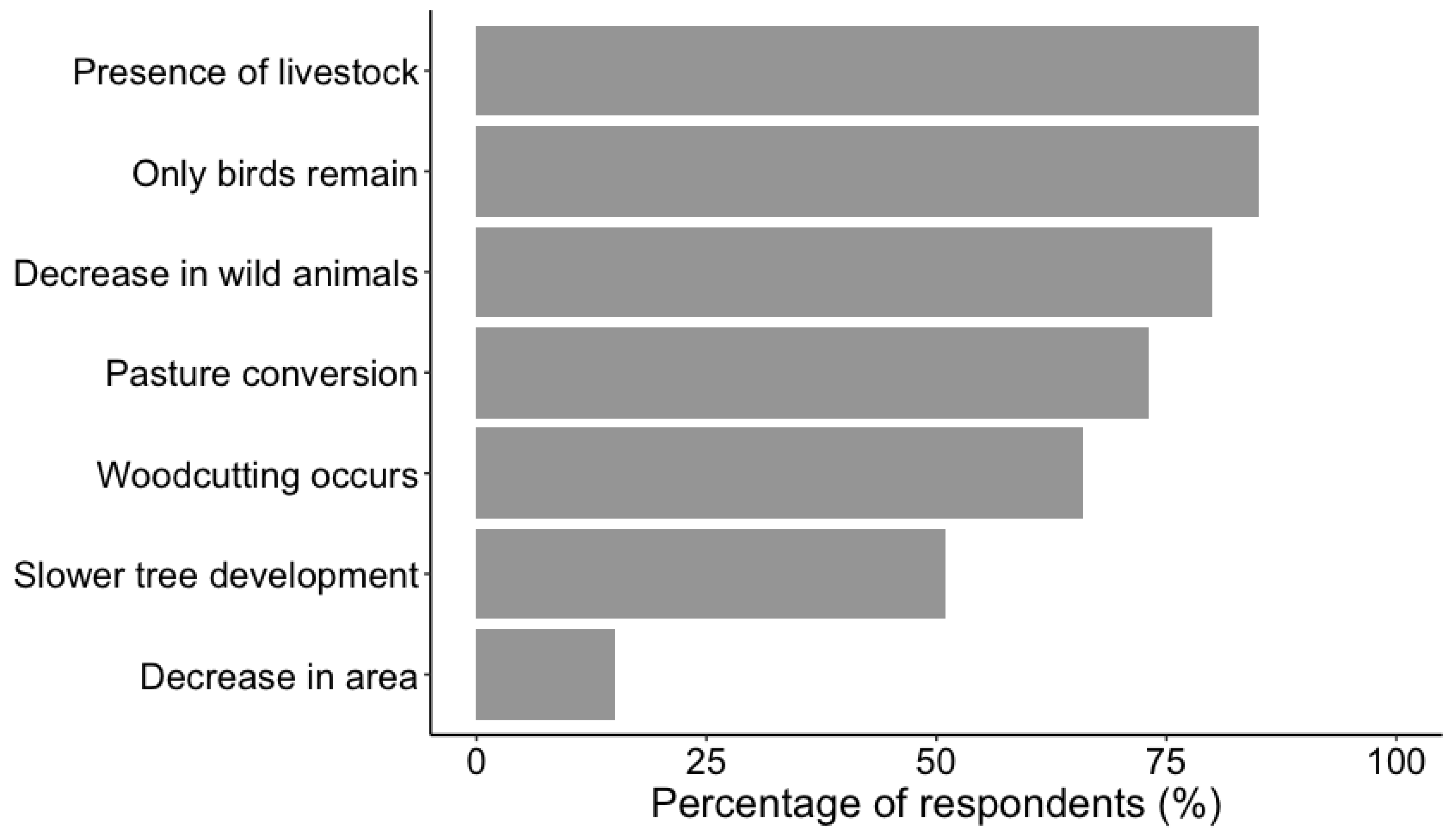

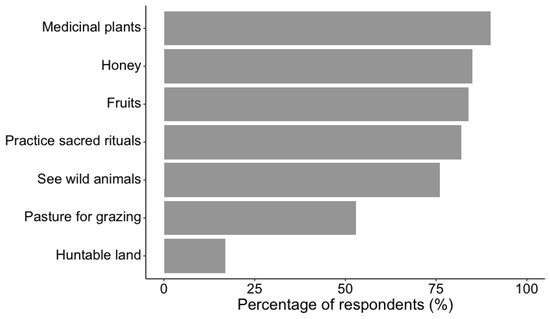

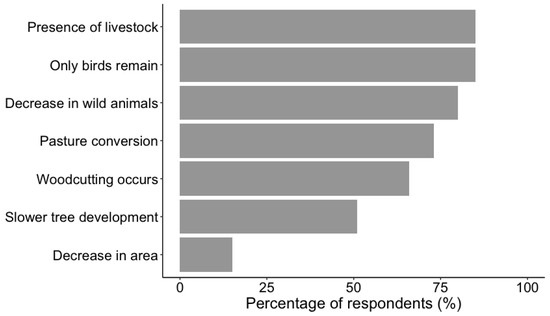

The vast majority (95%) of respondents felt that living near the sacred forest was advantageous. Residents view the Nakpadjoak forest as bringing rain essential for their crops, and 96% of respondents reporting rain as the greatest benefit of living near the forest, closely followed by access to medicinal plants (89%). Just over half (55%) of residents felt that entering the forest should be prohibited, while 45% felt that forest access should be permitted. Those supporting forest access were motivated by interest in harvesting medicinal plants (90%), harvesting honey (85%), gathering fruits (84%), and practicing sacred rituals (82%) (Figure 2). Most participants (81%) reported witnessing changes in the forest, with 79% noting wildlife declines and 70% observing that the forest has become livestock pasture (Figure 3). Additionally, 64% perceived wood cutting as contributing to the degradation of the sacred forest (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Motivations for local residents wanting access to Nakpadjoak sacred forest, Togo, based on 281 semi-structured surveys conducted in 2023.

Figure 3.

Changes witnessed by local residents in Nakpadjoak sacred forest, Togo, based on 281 semi-structured surveys conducted in 2023.

The vast majority of residents (92%) support protecting Nakpadjoak forest, with the majority (75%) believing that the local population should be responsible, compared to just over half (52%) preferring management by a non-governmental organization, and just under half (48%) preferring management by the national government (respondents could give more than one answer). Almost all (99%) respondents recommended that reforestation initiatives should be undertaken. Fruit trees (94%) and medicinal plants (92%) were favored for planting, followed by shade (79%), exotic (72%), and native (69%) tree species. In addition to reforestation within the forest boundaries, 94% of respondents supported planting trees within the surrounding communities, including at schools (87%), along paths (85%), and around houses (83%).

Most respondents identified wood (96%) and straw (90%) as their principal energy sources in the household, with only one person primarily using petroleum and none using natural gas. Of those using wood, 97% reported collecting wood from their farms, and 22% reported taking wood from the sacred forest. While 88% of respondents reported that cutting wood in the forest was not permitted, 40% knew at least one person who cut wood in the forest. The vast majority (94%) of respondents believed that cutting wood in the forest caused problems for the forest and/or surrounding communities. Most respondents (74%) thought that there were advantages to using natural gas over wood, 90% reported being willing to switch from using wood to natural gas, and 77% said that they could afford the price of filling a natural gas tank sufficient to support one family of five for one month.

3.2. Explanatory Variables

Cattle owners were 1.6 times more likely than non-cattle owners to want access to the sacred forest, while age had no effect (p = 0.070 and p = 0.316, respectively; Table 1). We also found that males were 2.2 times more likely than females to perceive a change in the forest (p = 0.024; Table 1). Additionally, cattle owners were 2.5 times more likely than non-cattle owners to perceive a change in the forest (p = 0.004; Table 1). Males were 2.0 times more likely than females to state a willingness to bear the cost of refilling a natural gas tank for approximately USD 7.23 (p = 0.040; Table 1). We also found evidence that younger respondents were more likely to bear the cost of refilling a natural gas tank (p < 0.001; Table 1). For each additional year of age, the odds of refilling a natural gas tank decreased by 4% (odds ratio = 0.959; Table 1). Respondents living in households less than 1 km from the sacred forest were better able to afford to refill a natural gas tank compared to those 2 km, or more than 3 km away (p = 0.023 and p = 0.005, respectively; Table 1). Specifically, those living 2 km, or more than 3 km away, from the sacred forest were 68% and 76% less likely, respectively, to be able to refill a natural gas tank (odds ratio = 0.321 and odds ratio = 0.242, respectively; Table 1).

Table 1.

Logistic regression results for forest access, perceived changes in forest, and financial ability to refill a natural gas tank (approximately USD 7.23), along with other variables of interest, from surveys conducted with individuals living near the sacred forest near Tami, Togo, in 2023. Significant results (p < 0.05) are highlighted in bold.

4. Discussion

Our findings showed the majority of the residents surrounding Nakpadjoak forest view the forest as being degraded and want it to be protected. The persistence of Nakpadjoak forest to date in an otherwise largely deforested landscape demonstrates the successful legacy of traditional protection for this sacred forest. Unfortunately, however, recent forest conservation efforts appear to have been limited by absent or weak enforcement of regulations, among other factors. Most respondents believed that the public, including the surrounding population, should not be allowed access to Nakpadjoak forest, and stated a desire for the forest to be managed by the local population and/or a non-governmental organization. Although most residents believe forest management should remain with the local community, unaddressed challenges appear to hinder effective protection of Nakpadjoak forest. For example, although most respondents felt that people should not be allowed to enter the forest in general, many wanted access themselves to collect medicinal plants, harvest honey, gather fruits, and practice traditional religious rituals. Cattle-owners (65% of residents) in particular were more likely to want access to the sacred forest, suggesting that an additional purpose of wanting access is for grazing cattle. This aligns with the perception of 70% of residents that the forest has become synonymous with livestock pasture, a major factor accelerating forest degradation and inhibiting forest regeneration.

Despite prohibitions on the exploitation of Nakpadjoak for wood cutting and livestock grazing, and sustainable use guidelines implemented elsewhere [12,43,44,45], an evident failure to enforce such regulations has led to the ongoing degradation of the forest. Although the overwhelming majority of residents value and support protecting the sacred forest, local economic and subsistence pressures now appear to override regulations and conservation traditions. Transitioning to alternative fuel sources—which residents reported being willing and able to do—could reduce pressure on the forest and support its conservation. Most residents reported that they considered natural gas to be preferable to wood as a household energy source and overwhelmingly reported that they would make the switch to use natural gas, given the opportunity. In addition, the majority of residents reported that they could afford the cost of natural gas, where filling a tank cost ~USD 7.23; males, younger respondents, and those living closer to the forest were more likely to be able to do so. Although natural gas is widely available in Togo’s cities (the closest city, Dapaong, is ~25 km by road), the lack of gas depots in rural villages such as Tami presents a barrier to encouraging residents to transition to this alternative household energy source. However, the interest and willingness of local residents to switch to natural gas presents a promising opportunity to reduce pressure on the use of the forest.

Given that most residents support prohibiting general access to the forest, enforcing such a policy could be a path forward. Hiring forest guardians could help prevent further degradation while encouraging compliance and enforcement of regulations. Monitoring plant abundances and locations [12,46] could inform a policy framework to encourage long-term species persistence in the sacred forest, and follow-up surveys could help evaluate the effectiveness of existing regulations. Forming a forest management committee [12] that represents local communities could facilitate forest management goals, which many include conservation initiatives, rule implementation, and conflict resolution related to forest rules. Such a committee could hire forest guardians to serve as conservation officers on the ground and report back to the committee. However, enforcing rules and holding people accountable could prove difficult if forest guardians are familiar with violators [47,48]. If local residents are employed to protect Nakpadjoak forest, they would likely face significant conflicts of interest in relation to family members, neighbors, and friends, making it challenging to uphold forest rules [47,49]. By contrast, effective governance and controlling corruption has been shown to mitigate forest degradation in this region [8]. Any fears related to sorcery and curses in the area that could complicate efforts to ensure the proper protection of the forest [49,50,51] should also be investigated and addressed.

Most respondents perceived that the forest has changed, recognizing wildlife declines and increases in livestock, both of which negatively affect the forest’s natural ecosystem. Local people also reported that the forest has become more pasture-like, due to tree cutting and increased browsing and grazing pressure, which can negatively affect plant survival [52,53,54]. Tree regeneration may also be hindered by the combined effects of rising temperatures [55] and irregular rainfall [10]. Decreasing tree density may have cascading effects on the forest’s structure, species composition, and dynamics [51,56,57,58]. For example, savanna species may begin to outcompete forest species [59]. In our study, 12% of respondents believed wood cutting was allowed, and 22% reported cutting wood in the sacred forest. Wood fuel is the main energy source of almost all households in this study, but wood cutting by hundreds of households is unsustainable in a 50-ha forest remnant. Livestock grazing and wood cutting alter habitats, consistent with residents’ perceptions that wildlife has declined in the forest. To reduce further forest degradation, we recommend that prohibitions on livestock and wood cutting in the forest be enforced.

Respondents reported supporting reforestation initiatives including fruit trees and medicinal plants. Exotic tree species were slightly favored over native species, although invasive plant species can sometimes outcompete and inhibit native species [32], as has been the case with Chromolaena odorata, Azadirachta indica (neem), and Mimosa invisa (creeping sensitive plant) in West Africa [60]. Although wood remains the primary household energy source [8], we found that 90% of respondents reported their willingness to switch to natural gas. If people living near the forest switch to using natural gas instead of wood fuel, the pressure of subsistence wood cutting may be reduced. Government subsidies on natural gas might encourage residents to shift to this fuel source [61], particularly in rural areas [62]. In this case, forest protection should be monitored, particularly to avoid a situation in which commercial wood cutting might nevertheless persist to provide some with an additional source of income [9,31].

Residents’ shifting from wood fuel to natural gas (and/or other alternative household fuels) could significantly decrease wood cutting in Togo and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, and we recommend increasing rural residents’ access to natural gas among other measures conducive to forest and woodland conservation in this region. Recent research in a nearby sacred forest in northern Togo, the Fosse de Doung, demonstrates extensive deforestation of this site due to logging, burning, and the establishment of crop plantations, despite traditional prohibitions protecting it [63]. This degradation is consistent with forest, woodland, and natural area destruction across the region of northern Togo, which during the period 1984–2020 lost ~72% of its woodlands, while built areas increased by 171% [64]. Some research in the tropics has found lower deforestation rates in community-managed forests than state-protected forests [65]. However, both community and state-protected areas in Togo have been subjected to severe overexploitation, driven in part by rapid population growth and domestic political conflicts, which has continued despite repeated initiatives to promote conservation by the central government and external donors.

Between 2015 and 2017, the United Nations Development Program’s Global Environmental Fund and Union Féminine des Savanes (UNIFESA) provided > USD 50,000 in financial support to address uncontrolled wood cutting, grazing, and bush fires in Nakpadjoak forest [66]. Among other measures, this funding appears to have been used for the installation of a fence surrounding the forest as well as beehives so that trees would no longer be cut down to harvest honey. However, in 2022 we found that all fencing had been removed, and the beehives had been abandoned, apparently unused, and observed multiple individuals cutting trees and herders leading herds of cattle through the forest during a short (1–2 h) visit. Thus, it appears that neither residents’ desire to protect the forest nor United Nations funding for forest protection and restoration have succeeded in preventing the ongoing degradation of Nakpadjoak forest; this may serve as an example of “the tragedy of the commons”, wherein individuals acting without restraint to maximize short-term gains collectively drive long-term environmental damage [67].

Solutions proposed to avoid the destruction of common property include conversion to private property or subjection to government regulation [68]. Regulation need not be by a central government, as there are many examples of local community-organized regulations that have worked to protect common resources, including in England, Japan, Peru, and Türkiye (Turkey), where communities have imposed restrictions that have worked well and endured for centuries, including in grasslands, parks, and forests [68,69,70]. Case studies around the world illustrate many communities’ successful organizing to maintain sustainable resource use. However, in many tropical countries, corruption and a lack of effective law enforcement undermine protection and enable widespread poaching, illegal logging, and habitat destruction in protected areas [8,71,72,73,74,75,76]. Some studies have suggested that residents may nevertheless prioritize traditional sacred and community forests [65,77]. Our findings highlight that despite the vast majority of residents expressing support for the protection of Nakpadjoak forest, neither internal support nor external funding appear to have hindered ongoing forest overexploitation.

Future research should investigate the relative importance of unresolved conflicts of interest, elite capture of resources, or other factors in this conservation failure [35]. Conflicts of interest between local practices and conservation strategies should be explored with a view to resolve them. In particular, governance effectiveness and control of corruption should be prioritized, as these have been shown as key to mitigating forest degradation in Africa [8,78]. Follow-up surveys could assess whether and how changing their principal household fuel source might affect local households, the Nakpadjoak sacred forest, and resident views of it, as limitations of this study include a reliance on subjective data and a short time frame. Future research and management should also focus on assessing and monitoring vegetation and wildlife inside the sacred forest in order to assess species occupancy, abundances, and distributions in response to conservation actions, or the lack thereof [35]. Monitoring both trees and wildlife (e.g., birds, arthropods, and other animals) in response to the protection (or decline) of this forest over time would provide an additional measure of its conservation value.

5. Conclusions

Wood fuel consumption significantly facilitates forest degradation in sub-Saharan Africa [8]. Our study demonstrates that hundreds of households surrounding Nakpadjoak forest consume wood fuel, and local traditions that protected this area as a sacred site do not appear sufficient to withstand current demographic pressures in the absence of effective conservation interventions. The majority of the residents surrounding Nakpadjoak forest view it as being degraded and want it to be protected, with most believing the public, including the surrounding population, should not be allowed access. However, most (70%) residents indicated that the forest is being transformed into livestock pasture. Nearly two-thirds of residents were cattle owners, and cattle owners were more likely to want access to the sacred forest. To prevent the destruction of Nakpadjoak forest, and the natural and cultural heritage it represents, prohibitions on wood cutting and livestock grazing in the forest must be prioritized to allow the forest to recover and regenerate.

The persistence of Nakpadjoak forest to date in an otherwise largely deforested landscape is one indication of the historic significance of sacred sites in Togo and West Africa [76]. To address a major factor driving the degradation of the forest, we recommend encouraging alternatives to wood cutting and consumption for household fuel. Increasing the number of depots where natural gas is distributed in rural areas may encourage the adoption of this household fuel alternative as a replacement for wood fuel, reducing pressure on local trees and woodland. Although most residents (96%) used wood as their primary fuel source, they overwhelmingly reported that they would switch to use natural gas, given the opportunity. Most (77%) respondents also indicated that they could afford to refill a natural gas tank, with males, younger respondents, and those living closer to the forest significantly more likely to be able to do so. Future conservation actions should follow up on ongoing interventions including increasing access to natural gas for local households while facilitating the protection of extant trees and restoration of degraded forest by planting and maintaining new trees [79]. Future research may assess the success or failure of such efforts and their implications for the conservation of this and other sacred sites in northern Togo and elsewhere in West Africa and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.F., Y.K., L.-E.M.K. and N.A.; methodology, B.F., Y.K., L.-E.M.K. and N.A.; software, B.F.; validation, B.F., Y.K., L.-E.M.K. and N.A.; formal analysis, B.F.; investigation, B.F., Y.K., L.-E.M.K. and N.A.; resources, N.A.; data curation, B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, B.F.; writing—review and editing, B.F. and N.A.; visualization, B.F.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Donors to the International Bird Conservation Partnership made this study possible.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, with research permits granted by the Government of the Republic of Togo (0209/MERF/SG/DRF, 0065/MERF/SG/DRF, 12 June 2024) and access to communities granted by their respective authorities.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all the residents around the sacred forest of Nakpadjoak who took the time to participate in this survey and to local community leaders for granting permission to conduct this research, particularly the mayor of the prefecture of Tône 3 and the chief of Tami. We thank Darren Rebar of Emporia State University for providing valuable statistical guidance and advice. We are also grateful to the reviewers and editors who provided constructive feedback that helped improve and shape the final version of this paper and to Ruthe J. Smith for proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, S.M.; Brandt, M.; Rasmussen, K.; Fensholt, R. Accelerating land cover change in West Africa over four decades as population pressure increased. Commun. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M.; Williams, D.R.; Kimmel, K.; Polasky, S.; Packer, C. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature 2017, 546, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Fleischer, L.R.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C.; Alewell, C.; Meusburger, K.; Modugno, S.; Schütt, B.; Ferro, V.; et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Heinrigs, P.; Heo, I. Agriculture, Food and Jobs in West Africa; West African Papers, No. 14; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, C.; Abdul-Rahim, A.S.; Mohd-Shahwahid, H.O.; Chin, L. Wood fuel consumption, institutional quality, and forest degradation in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a dynamic panel framework. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 74, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, L.C.; Richardson, R.B. Charcoal, livelihoods, and poverty reduction: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2013, 17, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent Evaluation Office; Global Environment Facility. Strategic Country Cluster Evaluation of Sahel and Sudan-Guinea Savanna Biomes; Evaluation Report No. 141; GEF IEO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); Division of Early Warning and Assessment (DEWA). Africa: Atlas of Our Changing Environment; UNEP-DEWA: Nairobi, Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kokou, K.; Adjossou, K.; Kokutse, A.D. Considering sacred and riverside forests in criteria and indicators of forest management in low wood producing countries: The case of Togo. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombate, A.; Folega, F.; Atakpama, W.; Dourma, M.; Wala, K.; Goïta, K. Characterization of land-cover changes and forest-cover dynamics in Togo between 1985 and 2020 from Landsat images using Google Earth Engine. Land 2022, 11, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubreville, A. Les forêts du Dahomey et du Togo. Bull. Com. D’études Hist. Sci. L’A.O.F 1937, 20, 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tchamiè, T.T.K. Enseignements à tirer de l’hostilité des populations locales à l’égard des aires protégées au Togo. Unasylva 1994, 176, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère du Plan, de l’Aménagement du Territoire, de l’Habitat et de l’Urbanisme (MPTHU). Mise en Œuvre d’un Programme de Réhabilitation des Aires Protégées au Togo, Etude d’une Stratégie Globale de Mise en Valeur; COM-STABEX: Lomé, Togo, 2001; pp. 91–94.

- Dowsett-Lemaire, F.; Dowsett, R.J. The Birds of Benin and Togo, 1st ed.; Tauraco Press: Sumène, France, 2019; pp. 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Akodéwou, A.; Oszwald, J.; Saïdi, S.; Gazull, L.; Akpavi, S.; Akpagana, K.; Gond, V. Land use and land cover dynamics analysis of the Togodo Protected Area and its surroundings in southeastern Togo, West Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsri, H.K.; Konko, Y.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Abotsi, K.E.; Kokou, K. Changes in the West African forest-savanna mosaic, insights from central Togo. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assou, D.; D’Cruze, N.; Kirkland, H.; Auliya, M.; Macdonald, D.W.; Segniagbeto, G.H. Camera trap survey of mammals in the Fazao-Malfakassa National Park, Togo, West Africa. Afr. J. Ecol. 2021, 59, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Bhagwat, S.; Higgins-Zogib, L.; Lassen, B.; Verschuuren, B.; Wild, R. Conservation of biodiversity in sacred natural sites in Asia and Africa: A review of the scientific literature. In Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture, 1st ed.; Verchuuren, B., Wild, R., McNeely, J.A., Oviedo, G., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Juhé-Beaulaton, D. Bois sacrés et conservation de la biodiversité (sud Togo et Bénin). In Afrique, Terre D’histoire, 1st ed.; Deslaurier, C., Juhé-Beaulaton, D., Eds.; Karthala: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tatay, J.; Merino, A. What is sacred in sacred natural sites? A literature review from a conservation lens. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokou, K.; Sokpon, N. Les forêts sacrées du couloir du Dahomey. Bois For. Des Trop. 2006, 288, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, A. Consequences of wooded shrine rituals on vegetation conservation in West Africa: A case study from the Bwaba cultural area (West Burkina Faso). Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbie, A.R.; Freudenberger, M.S. Sacred groves in Africa: Forest patches in transition. In Forest Patches in Tropical Landscapes, 1st ed.; Schelhas, J., Greenburg, R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 300–324. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, L.; Kokou, K.; Todd, S. Comparison of the ecological value of sacred and nonsacred community forests in Kaboli, Togo. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 11, 1940082918758273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, K.; Ffrench-Constant, R.; Gordon, I. Sacred sites as hotspots for biodiversity: The Three Sisters Cave complex in coastal Kenya. Oryx 2010, 44, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.R.; Tanimola, A.A.; Olubode, O.S. Complexities of local cultural protection in conservation: The case of an endangered African primate and forest groves protected by social taboos. Oryx 2018, 52, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceperley, N.; Montagnini, F.; Natta, A. Significance of sacred sites for riparian forest conservation in Central Benin. Bois For. Trop. 2010, 303, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra-van der Horst, G.; Hovorka, A.J. Fuelwood: The “other” renewable energy source for Africa? Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, P.S.; Kumar, M.; Sundarapandian, S.M. Spirituality and ecology of sacred groves in Tamil Nadu, India. Unasylva 2003, 54, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ihemezie, E.J.; Albaladejo-García, J.A.; Stringer, L.C.; Dallimer, M. Integrating biocultural conservation and sociocultural valuation in the management of sacred forests: What values are important to the public? People Nat. 2023, 5, 2074–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.O.N. Sacred groves for forest conservation in Ghana’s coastal savannas: Assessing ecological and social dimensions. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2005, 26, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyare, A.K.; Holbech, L.H.; Arcilla, N. Great expectations, not-so-great performance: Participant views of community-based natural resource management in Ghana, West Africa. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 7, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, R.E.; Stakhanov, O.V. Prospects for enhancing livelihoods, communities, and biodiversity in Africa through community-based forest management: A critical analysis. Local Environ. 2008, 13, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollins, J. Under Fire: Five Myths About Wood Fuel in Sub-Saharan Africa. CIFOR Forest News, 2020; p. 66346. Available online: https://forestsnews.cifor.org/66346/under-fire-five-facts-about-wood-fuel-in-sub-saharan-africa?fnl=en (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Asenso Barnieh, B.; Jia, L.; Menenti, M.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, Y. Mapping land use land cover transitions at different spatiotemporal scales in West Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U.; Poch, R.M.; Scarciglia, F.; Francis, M.L. A carbon-sink in a sacred forest: Biologically-driven calcite formation in highly weathered soils in Northern Togo (West Africa). CATENA 2021, 198, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.40.0); Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project: Xx: Laax, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: http://qgis.osgeo.org (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- John, F.A.V.S.; Brockington, D.; Bunnefeld, N.; Duffy, R.; Homewood, K.; Jones, J.P.G.; Keane, A.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Nuno, A.; Razafimanahaka, H.J. Research ethics: Assuring anonymity at the individual level may not be sufficient to protect research participants from harm. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 196, 208–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, (Version 4.2.2.); R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Mandondo, A. Situating Zimbabwe’s Natural Resource Governance Systems in History; Occasional Paper No. 32; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oyono, P.R.; Biyong, M.B.; Samba, S.K. Beyond the decade of policy and community euphoria: The state of livelihoods under new local rights to forest in rural Cameroon. Conserv. Soc. 2012, 10, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, B.D.; Brown, K.; Helmisaari, H.S.; Vangueloca, E.; Stupak, I.; Evans, A.; Clarke, N.; Guidi, C.; Bruckman, V.J.; Vangueloca, E.; et al. Sustainable forest biomass: A review of current residue harvesting guidelines. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2011, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franta, B.C. Analyzing Avian Habitat Associations in the Flint Hills and Ioway Tribal National Park. Master’s Thesis, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.C.; Marks, S.A. Transforming rural hunters into conservationists: An assessment of community-based wildlife management programs in Africa. World Dev. 1995, 23, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songorwa, A.N. Community-Based Wildlife Management: The Case Study of Selous Conservation Programme in Tanzania. Ph.D. Thesis, Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moreto, W.D.; Brunson, R.K.; Braga, A.A. ‘Anything we do, we have to include the communities’: Law enforcement rangers’ attitudes towards and experiences of community-ranger relations in wildlife protected areas in Uganda. Br. J. Criminol. 2017, 57, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschiere, P. The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa, 1st ed.; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Poppe, J. Conservation’s ambiguities: Rangers on the periphery of the W park, Burkina Faso. Conserv. Soc. 2012, 10, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshra, B.P.; Tripathi, O.P.; Tripathi, R.S.; Pandey, H.N. Effects of anthropogenic disturbance on plant diversity and community structure of a sacred grove in Meghalaya, northeast India. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloo, R.C.; Kharlukhi, L.; Jeeva, S.; Mishra, B.P. Status of medicinal plants in the disturbed and undisturbed sacred forests of Meghalaya, northeast India: Population structure and regeneration efficacy of some important species. Curr. Sci. 2006, 90, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wassie, A.; Sterck, F.J.; Teketay, D.; Bongers, F. Effects of livestock exclusion on tree regeneration in church forests of Ethiopia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchinguilou, A.; Jalloh, A.; Thomas, T.S.; Nelson, G.C. West African Agriculture and Climate Change; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 353–382. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, R.; Ashworth, L.; Galetto, L.; Aizen, M.A. Plant reproductive susceptibility to habitat fragmentation: Review and synthesis through a meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Pascal, J.P.; Kushalappa, C.G. Les forêts sacrées du Kodagu en Inde: Écolgie et religion. Bois For. Trop. 2006, 288, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossi, A.; Mazalo, K.P.; Novinyo, S.K.; Kouami, K. Impacts of traditional practices on biodiversity and structural characteristics of sacred groves in northern Togo, West Africa. Acta Oecologica 2021, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blench, R.; Dendo, M. Cultural and biological interactions in the savanna woodlands of Northern Ghana: Sacred forests and management of trees. In Proceedings of the Conference Trees, Rain, and Politics in Africa, Oxford, UK, 29 September–1 October 2004; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kokou, K.; Afiademanyo, K.M.; Agboyi, L.K. Invasive alien species in Togo (West Africa). Invasive Alien Species Obs. Issues Around World 2021, 1, 291–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, B. Household energy preferences for cooking in urban Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 3787–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.; Ali, A. Patterns and determinants of household use of fuels for cooking: Empirical evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Energy 2016, 117, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakpama, W.; Badjare, B.; Aladji, E.Y.K.; Batawila, K.; Akpagana, K. Dégradation alarmante des ressources forestières de la forêt classée de la fosse de Doungh au Togo. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2023, 6, 485–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlui, K.S.; Atakpama, W.; von Wehrden, H.; Bah, A.; Kola, E.; Anthony-Krueger, C.; Egbelou, H.; Kokou, K.B.; Boukpessi, T. Anthropogenic Threats to Degraded Forest Land in the Savannahs’ Region of Togo from 1984 to 2020, West Africa. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2024, 12, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Bolland, L.A.; Ellis, E.A.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Reyes-García, V. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 268, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP GEF SGP, Gestion Inclusive de la Forêt Communautaire de Nakpadjaog, 2015–2017. Available online: https://sgp.undp.org/spacial-itemid-projects-landing-page/spacial-itemid-project-search-results/spacial-itemid-project-detailpage.html?view=projectdetail&id=22787 (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphiné, N.; Yagkuag, A.T.; Cooper, R.J. A new location and altitude for Royal Sunangel Heliangelus regalis. Cotinga 2008, 30, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Feeny, D.; Berkes, F.; Mccay, B.J.; Acheson, J.M. The tragedy of the commons: Twenty-two years later. Hum Ecol. 1990, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repetto, R. World Enough and Time: Successful Strategies for Resource Management; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, L.M.; Trigg, S.N.; McDonald, A.K.; Astiani, D.; Hardiono, Y.M.; Siregar, P.; Caniago, I.; Kasischke, E. Lowland forest loss in protected areas of Indonesian Borneo. Science 2004, 303, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcilla, N.; Holbech, L.H.; O’Donnell, S. Severe declines of forest understory birds follow illegal logging in Ghana, West Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 188, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboumba, L.-E.M.; Di Lecce, I.; Afiademanyo, K.M.; Kourdjouak, Y.; Arcilla, N. Assessing Threats to Fazao-Malfakassa National Park, Togo, Using Birds as Indicators of Biodiversity Conservation. Land 2025, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Levi, T.; Ripple, W.J.; Zárrate-Charry, D.A.; Betts, M.G. A forest loss report card for the world’s protected areas. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C. The Rainforests of West Africa; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Burivalova, Z.; Hua, F.; Pin Koh, L.; Garcia, G.; Putz, F. A critical comparison of conventional, certified, and community management of tropical forests for timber in terms of environmental, economic, and social variables. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, P.; Schure, J.; Eba’a Atyi, R.; Gumbo, D.; Okeyo, I.; Awono, A. Woodfuel policies and practices in selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa—A critical review. Bois For. Trop. 2019, 340, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboumba, L.-E.M. À la Rescousse de la Forêt Sacrée de Tami: Un Sanctuaire Togolais Pour les Oiseaux en Peril. 2024. Available online: https://www.birdpartners.org/post/%C3%A0-la-rescousse-de-la-for%C3%AAt-sacr%C3%A9e-de-tami-un-sanctuaire-togolais-pour-les-oiseaux-en-p%C3%A9ril (accessed on 20 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).