Genetic Sex Determination of Free-Ranging Short-Finned Pilot Whales from Blow Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Species

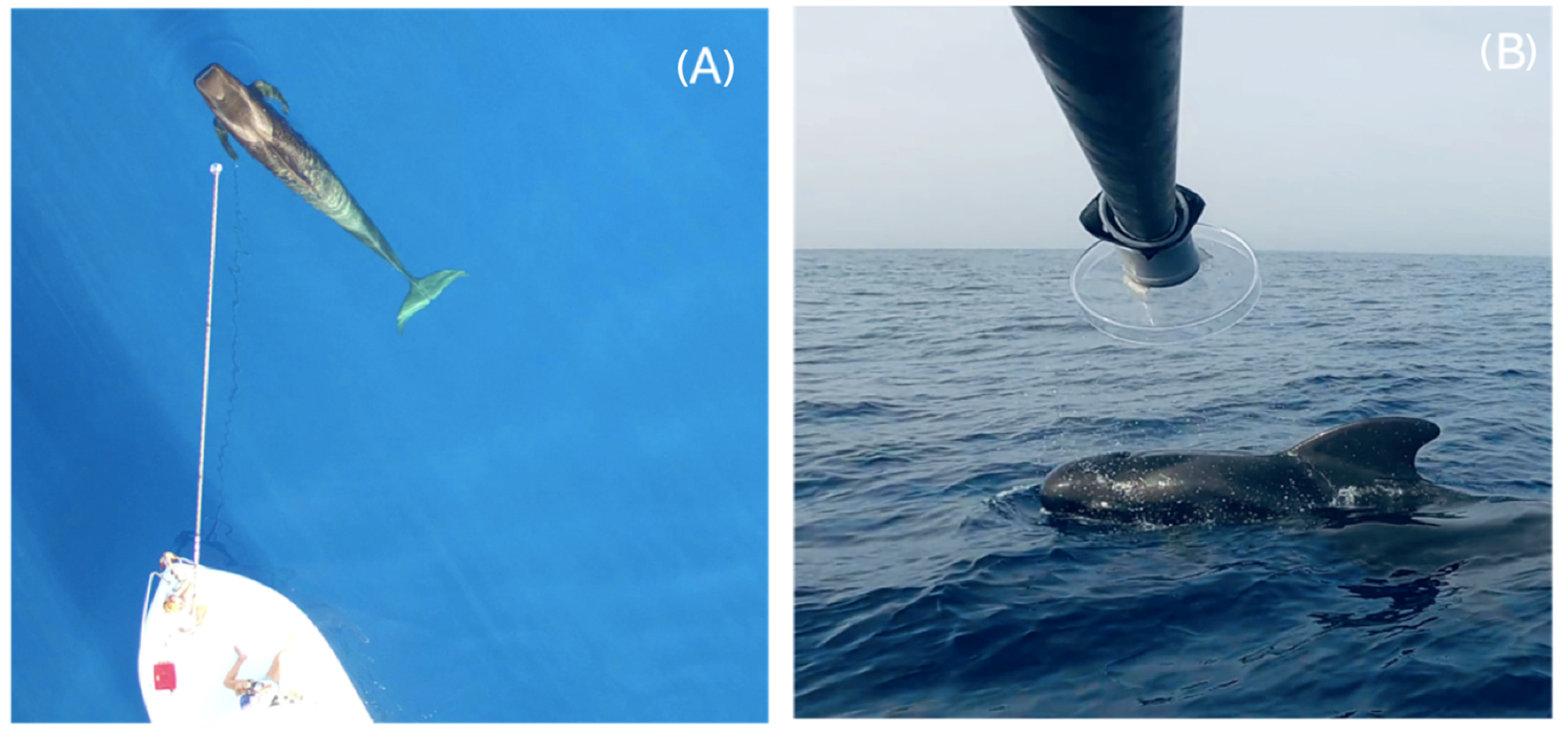

2.2. Blow Sampling at Sea

2.3. Laboratory Sample Preparation

2.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.5. Sex Determination

2.5.1. Classical Multiplex-PCR Methodology

2.5.2. Novel FCB17 Multiplex-PCR Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braulik, G.T.; Taylor, B.L.; Minton, G.; di Sciara, G.N.; Collins, T.; Rojas-Bracho, L.; Crespo, E.A.; Ponnampalam, L.S.; Double, M.C.; Reeves, R.R. Red-list status and extinction risk of the world’s whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Würsig, B. (Eds.) Helping Marine Mammals Cope with Humans. In Marine Mammals: The Evolving Human Factor; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 425–450. [Google Scholar]

- Tyne, J.A.; Loneragan, N.R.; Johnston, D.W.; Pollock, K.H.; Williams, R.; Bejder, L. Evaluating monitoring methods for cetaceans. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 201, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijsseldijk, L.L.; Doeschate, M.T.I.T.; Brownlow, A.; Davison, N.J.; Deaville, R.; Galatius, A.; Gilles, A.; Haelters, J.; Jepson, P.D.; Keijl, G.O.; et al. Spatiotemporal mortality and demographic trends in a small cetacean: Strandings to inform conservation management. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 249, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Bejder, L.; Green, L.; Johnson, C.; Keeling, L.; Noren, D.; Van der Hoop, J.; Simmonds, M. Anthropogenic Threats to Wild Cetacean Welfare and a Tool to Inform Policy in This Area. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, S.E.; King, C.D.; Chou, E.; Chin, S.C.; Rekdahl, M.; Rosenbaum, H.C. Using environmental DNA to detect whales and dolphins in the New York Bight. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 3, 820377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.V.; Migneault, A.; Dracott, K.; Glover, R.D. Seas the DNA? Limited detection of cetaceans by low-volume environmental DNA transect surveys. Environ. DNA 2023, 5, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, R.M.; Frasier, T.R.; Rolland, R.M.; White, B.N. Molecular identification of individual North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) using free-floating feces. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2010, 26, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, J.L.; Pirotta, V.; Harvey, E.; Smith, A.; Buchmann, J.P.; Ostrowski, M.; Eden, J.-S.; Harcourt, R.; Holmes, E.C. Virological Sampling of Inaccessible Wildlife with Drones. Viruses 2018, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centelleghe, C.; Carraro, L.; Gonzalvo, J.; Rosso, M.; Esposti, E.; Gili, C.; Bonato, M.; Pedrotti, D.; Cardazzo, B.; Povinelli, M.; et al. The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to sample the blow microbiome of small cetaceans. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, E.A.; Hunt, K.E.; Kraus, S.D.; Rolland, R.M. Quantifying hormones in exhaled breath for physiological assessment of large whales at sea. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartzok, D. Breathing. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals; Elsevier eBooks: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Raudino, H.C.; Tyne, J.A.; Smith, A.; Ottewell, K.; McArthur, S.; Kopps, A.M.; Chabanne, D.; Harcourt, R.G.; Pirotta, V.; Waples, K. Challenges of collecting blow from small cetaceans. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Nuuttila, H. Don’t Hold Your Breath: Limited DNA Capture using Non-Invasive Blow Sampling for Small Cetaceans. Aquat. Mamm. 2020, 46, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, S.; Rogan, A.; Baker, C.S.; Dagdag, R.; Redlinger, M.; Polinski, J.; Urban, J.; Sremba, A.; Branson, M.; Mashburn, K.; et al. Genetic, Endocrine, and Microbiological Assessments of Blue, Humpback and Killer Whale Health using Unoccupied Aerial Systems. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2021, 45, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, P.A. Pilot Whales: Globicephala melas and G. macrorhynchus. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 2nd ed.; Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2009; pp. 847–852. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya, T.; Marsh, H. Life history and reproductive biology of the short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhynchus, off the Pacific coast of Japan. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 1984, 6, 259–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.; Franks, D.W.; Nattrass, S.; Cant, M.A.; Bradley, D.L.; Giles, D.; Balcomb, K.C.; Croft, D.P. Postreproductive lifespans are rare in mammals. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.A. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya, T.; Matsui, S. Age determination and growth of the short finned pilot whale off the pacific coast of Japan. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 1984, 35, 57–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, E. Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals; Würsing, B.G., Thewissen, J.G.M., Kovacs, K.M., Eds.; Academic Press/Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1010–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Servidio, A.; Pérez-Gil, E.; Pérez-Gil, M.; Cañadas, A.; Hammond, P.S.; Martín, V. Site fidelity and movement patterns of short-finned pilot whales within the Canary Islands: Evidence for resident and transient populations. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, P.; Glarou, M.; Sprogis, K.R. Decreased resting and nursing in short-finned pilot whales when exposed to louder petrol engine noise of a hybrid whale-watch vessel. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leray, M.; Yang, J.Y.; Meyer, C.P.; Mills, S.C.; Agudelo, N.; Ranwez, V.; Machida, R.J. A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity: Application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Front. Zool. 2013, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasankar, P.; Anoop, B.; Reynold, P.; Krishnakumar, P.K.; Kumaran, P.L.; Afsal, V.V.; Anoop, A.K. Molecular identification of Delphinids and Finless Porpoise (Cetacea) from the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. Zootaxa 2008, 1853, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosel, P.E. PCR-based sex determination in Odontocete cetaceans. Conserv. Genet. 2003, 4, 647–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, F.C.; Friesen, M.K.; Littlejohn, R.P.; Clayton, J.W. Microsatellites from the beluga whale Delphinapterus leucas. Mol. Ecol. 1996, 5, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Quérouil, S.; Dinis, A.; Nicolau, C.; Ribeiro, C.; Freitas, L.; Kaufmann, M.; Fortuna, C. Population structure of short-finned pilot whales in the oceanic archipelago of Madeira based on photo-identification and genetic analyses: Implications for conservation. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2013, 23, 758–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, É.N.; Sremba, A.L.; Keen, E.M.; Robinson, N.; Dundas, A.; Steel, D.; Gaggiotti, O.E. Collecting baleen whale blow samples by drone: A minimally intrusive tool for conservation genetics. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2024, 2024, e13957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.; Rogan, A.; Zadra, C.; Larsen, O.; Rikardsen, A.H.; Waugh, C. Blowing in the Wind: Using a Consumer Drone for the Collection of Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Blow Samples during the Arctic Polar Nights. Drones 2023, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groch, K.; Blazquez, D.; Marcondes, M.; Santos, J.; Colosio, A.; Delgado, J.D.; Catão-Dias, J. Cetacean morbillivirus in Humpback whales’ exhaled breath. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingramm, F.M.J.; Keeley, T.; Whitworth, D.J.; Dunlop, R.A. Relationships between blubber and respiratory vapour steroid hormone concentrations in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Aquat. Mamm. 2019, 45, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, A.; Yeates, L.; Pasamontes, A.; Siebe, C.; Zrodnikov, Y.; Simmons, J.; McCartney, M.; Deplanque, J.-P.; Wells, R.; Davis, C. Metabolite content profiling of bottlenose dolphin exhaled breath. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10616–10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apprill, A.; Miller, C.A.; Moore, M.J.; Durban, J.W.; Fearnbach, H.; Barrett-Lennard, L.G. Extensive core microbiome in drone-captured whale blow supports a framework for health monitoring. MSystems 2017, 2, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Afonso, L.; Alves, F.; Dinis, A.; Ferreira, R.; Correia, A.M.; Valente, R.; Gil, Á.; Castro, L.F.C.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; et al. Hidden in the blow—A matrix to characterise cetaceans’ respiratory microbiome: Short-finned pilot whale as case study. Metabarcoding Metagenomics 2024, 8, e121060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, C.; Dupuis, A.; Gero, S.; Frasier, T. A Sexing Technique for Highly Degraded Cetacean DNA. Aquat. Mamm. 2017, 43, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, J.; Sneath, H.; Ovenden, J.; Broderick, D.; Bonde, R. Sexing Sirenians: Validation of Visual and Molecular Sex Determination in Both Wild Dugongs (Dugong dugon) and Florida Manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris). Aquat. Mamm. 2009, 35, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, P.; Nestler, A.; Rubio, N.; Robertson, K.; Mesnick, S. Interfamilial characterization of a region of the ZFX and ZFY genes facilitates sex determination in cetaceans and other mammals. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchale, M.; Broderick, D.; Ovenden, J.R.; Lanyon, J.M. A PCR assay for gender assignment in dugong (Dugong dugon) and West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus). Mol. Ecol. Res. 2008, 8, 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Shen, Y.; McCord, B. The Development of Reduced Size STR Amplicons as Tools for Analysis of Degraded DNA. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querouil, S.; Freitas, L.; Cascão, I.; Alves, F.; Dinis, A.; Almeida, J.; Prieto, R.; Borràs, S.; Matos, J.; Mendonça, D.; et al. Molecular insight into the population structure of common and spotted dolphins inhabiting the pelagic waters of the Northeast Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 2010, 157, 2567–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.; Faria, D.; Cunha, H.; Santos, T.; Colosio, A.; Barbosa, L.; Freire, M.; Farro, A. Low Genetic Diversity of the Endangered Franciscana (Pontoporia blainvillei) in Its Northernmost, Isolated Population (FMAIa, Espírito Santo, Brazil). Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 608276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, A.; Querouil, S.; Magalhães, S.; Silva, M.; Prieto, R.; Matos, J.; Santos, R. Population genetics and social organization of the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) in the Azores inferred by microsatellite analyses. Can. J. Zool. 2009, 87, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowska, E.; Nowak, Z.; Van Elk, C.; Foote, A.D.; Wahlberg, M. Determining Genotypes from Blowhole Exhalation Samples of Harbour Porpoises (Phocoena phocoena). Aquat. Mamm. 2014, 40, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, D.N.; Zadra, C.J.; Friedlaender, A.S.; Parks, S.E.; Pensarosa, A.; Rogan, A.; Shorter, K.A.; Urbán, J.; Kerr, I. Deployment of biologging tags on free swimming large whales using uncrewed aerial systems. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 221376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer | Sequence | Amplicon Size |

|---|---|---|

| SRY forward | CCC ATG AAC GCA TTC ATT GTG TGG | ~225 bp |

| SRY reverse | ATT TTA GCC TTC CGA CGA GGT CGA TA | |

| ZFX/ZFY forward | ATA ATC ACA TGG AGA GCC ACA AGC T | ~445 bp |

| ZFX/ZFY reverse | GCA CTT CTT TGG TAT CTG AGA AAG T | |

| FCB17 forward | TCA GCC TCT ATA ACG TCC TGA GC | ~170 bp |

| FCB17 reverse | ATG GGG ACT GCC TAT ATT AGT CAG |

| Individual ID | DNA (miniCOI) | Classical Multiplex-PCR | Novel FCB17 Multiplex-PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | R.I. | Sex | R.I. | ||

| 24Gm01 | + | − | 0 | F | 1 |

| 24Gm02 | + | − | 0 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm03 | + | − | 0 | F | 2 |

| 24Gm04 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm05 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm06 | + | − | 0 | F | 2 |

| 24Gm07 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm08 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm09 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm10 | + | − | 0 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm11 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm12 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm13 | + | M | 2 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm14 | + | − | 0 | U | 4 |

| 24Gm15 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm16 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm17 | + | − | 0 | U | 4 |

| 24Gm18 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm19 | 0 | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm20 | + | M | 2 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm21 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm22 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm23 | + | − | 0 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm24 | + | − | 0 | U | 4 |

| 24Gm25 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm26 | + | M | 2 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm27 | + | M | 2 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm28 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm29 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm30 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm31 | + | M | 2 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm32 | + | M | 1 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm33 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm34 | + | − | 0 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm35 | + | − | 0 | F | 2 |

| 24Gm36 | + | − | 0 | M | 1 |

| 24Gm37 | + | − | 0 | U | 4 |

| 24Gm38 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| 24Gm39 | + | M | 2 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm40 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm41 | + | M | 2 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm42 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm43 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm44 | + | − | 0 | M | 3 |

| 24Gm45 | + | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| 24Gm46 | + | − | 0 | M | 2 |

| 24Gm47 | + | − | 0 | F | 3 |

| eDNA C1 | + | + | 1 | + | 1 |

| eDNA C2 | + | + | 3 | + | 1 |

| eDNA C3 | + | − | 0 | + | 1 |

| eDNA C4 | + | + | 2 | + | 1 |

| eDNA C5 | + | + | 1 | + | 1 |

| Sample N.C. | − | − | 0 | − | 0 |

| PCR N.C. | − | − | 0 | − | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arranz, P.; Coya, R.; Turac, E.; Miralles, L. Genetic Sex Determination of Free-Ranging Short-Finned Pilot Whales from Blow Samples. Conservation 2024, 4, 860-870. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation4040051

Arranz P, Coya R, Turac E, Miralles L. Genetic Sex Determination of Free-Ranging Short-Finned Pilot Whales from Blow Samples. Conservation. 2024; 4(4):860-870. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation4040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleArranz, Patricia, Ruth Coya, Elena Turac, and Laura Miralles. 2024. "Genetic Sex Determination of Free-Ranging Short-Finned Pilot Whales from Blow Samples" Conservation 4, no. 4: 860-870. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation4040051

APA StyleArranz, P., Coya, R., Turac, E., & Miralles, L. (2024). Genetic Sex Determination of Free-Ranging Short-Finned Pilot Whales from Blow Samples. Conservation, 4(4), 860-870. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation4040051