On the Factors Influencing Banking Satisfaction and Loyalty: Evidence from Denmark

Abstract

:1. Introduction

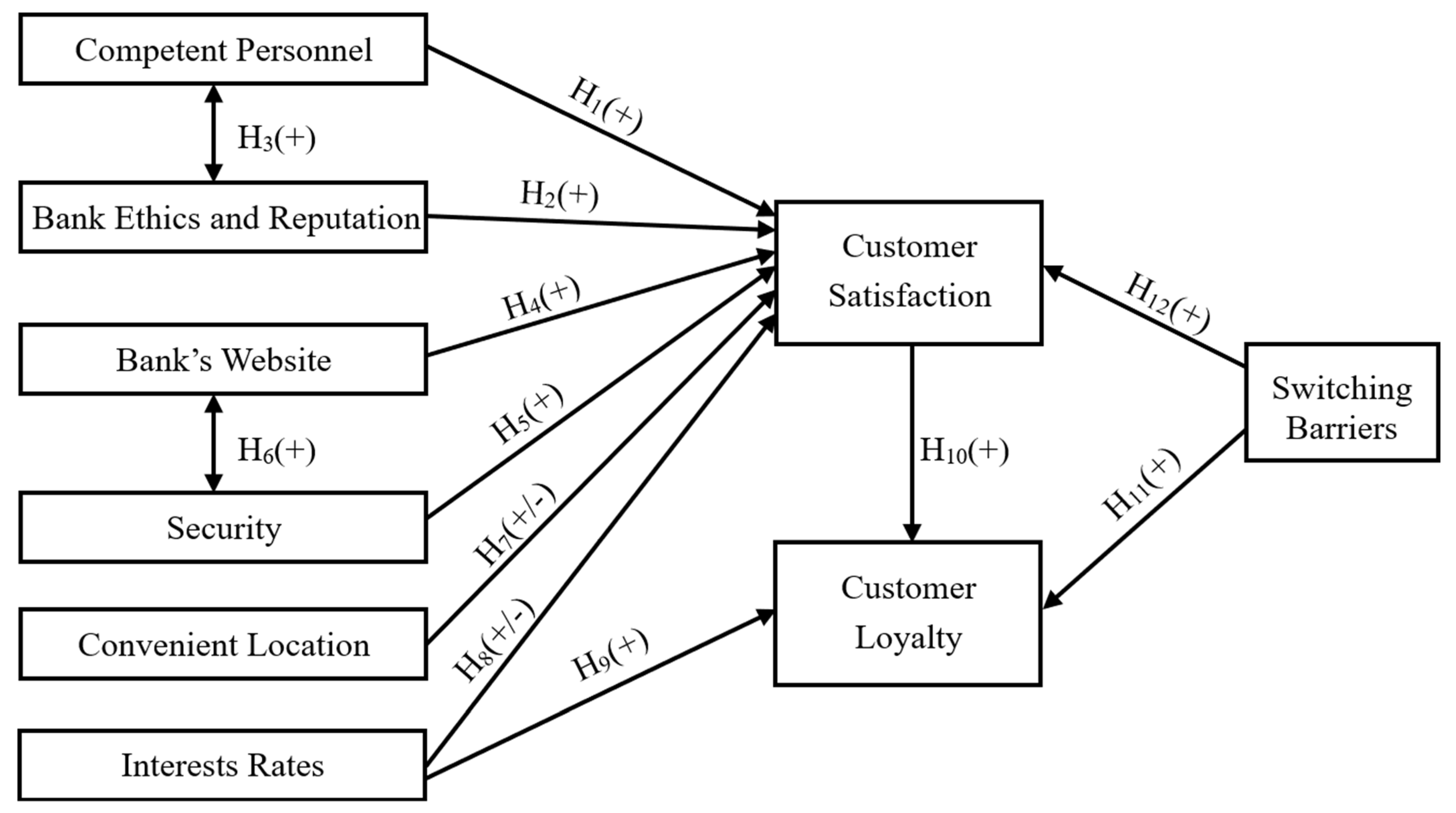

2. Conceptual Framework and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Customer Satisfaction and Its Antecedents

2.2. Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty

2.3. The Influence of Switching Barriers on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty

3. Methods

3.1. The Questionnaire and Measurement

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Estimation of the Measurement Model

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alok, K. R., & Srivastava, M. (2013). The antecedents of customer loyalty: An empirical investigation in life insurance context. Journal of Competitiveness, 5(2), 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. (2016). Internet banking service quality and its implication on e-customer satisfaction and e-customer loyalty. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(3), 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneli Järvinen, R. (2014). Consumer trust in banking relationships in Europe. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 32(6), 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. W. (1996). The relationship between culture and perception of ethical problems in international marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, C. k., Oni, A. A., Adewoye, O. J., & Eweoya, I. O. (2016). E-banking users’ behaviour: E-service quality, attitude, and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(3), 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. A., Darzi, M. A., & Parrey, S. H. (2018). Antecedents of customer loyalty in banking sector: A mediational study. Vikalpa, 43(2), 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonlertvanich, K. (2019). Service quality, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: The moderating role of main-bank and wealth status. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(1), 278–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhler, R. N., De Oliveira Santini, F., Junior Ladeira, W., Rasul, T., Perin, M. G., & Kumar, S. (2024). Customer loyalty in the banking sector: A meta-analytic study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(3), 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, T. A., Frels, J. K., & Mahajan, V. (2003). Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1994). Servperf versus SERVQUAL—Reconciling performance-based and perceptions-minus-expectations measurement of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danmarks Statistik. (2024). It-anvendelse i befolkningen 2024. Danmarks Statistik. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, J. G. (2024). Satisfaction leads to loyalty—Or could loyalty lead to satisfaction? Investigating brand usage and satisfaction levels in consumer banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(7), 1614–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, T. (2009). Trust as the key to loyalty in business-to-consumer exchanges: Trust building measures in the banking industry (1st ed.). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egala, S., Boateng, D., & Aboagye Mensah, S. (2021). To leave or retain? An interplay between quality digital banking services and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(7), 1420–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, K. M. (Ed.). (2010). Consumer behaviour: A nordic perspective. Studentlitteratur AB. [Google Scholar]

- El-Manstrly, D. (2016). Enhancing customer loyalty: Critical switching cost factors. Journal of Service Management, 27(2), 144–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPSI Rating. (2021). Danskernes tilfredshed med bankerne er i frit fald. T. E. R. Group. Available online: http://www.epsi-denmark.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-09-20-EPSI-Bank-Branchestudie-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Fatma, M., & Rahman, Z. (2016). Consumer responses to CSR in Indian banking sector. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 13(3), 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M., Rahman, Z., & Khan, I. (2015). Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: The mediating role of trust. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(6), 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R., Rahman, Z., & Qureshi, M. N. (2014). Measuring customer experience in banks: Scale development and validation. Journal of Modelling in Management, 9(1), 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, P., & Cunningham, J. B. (2004). Consumer switching behavior in the Asian banking market. Journal of services Marketing, 18(3), 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (Eds.). (2021). Evaluation of reflective measurement models. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (pp. 75–90). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, R., Abdul Subar, N., & Ibrahim, K. (2020). Service quality of Islamic banks: Satisfaction, loyalty and the mediating role of trust. Islamic Economic Studies, 28(1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (1959). The motivation to work (2nd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M. C. (2023). A systematic literature review of exploratory factor analyses in management. Journal of Business Research, 164, 113969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J. P., & Solomon, P. (2006). The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intention, and job performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(3), 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. (2011). Consumer loyalty on the grocery product market: An empirical application of Dick and Basu’s framework. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(5), 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. A., Mothersbaugh, D. L., & Beatty, S. E. (2000). Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. A., Reynolds, K. E., Mothersbaugh, D. L., & Beatty, S. E. (2007). The positive and negative effects of switching costs on relational outcomes. Journal of Service Research: JSR, 9(4), 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R., Jaiswal, D., & Mishra, S. (2017). The investigation of service quality dimensions, customer satisfaction and corporate image in Indian public sector banks: An application of structural equation model (SEM). Vision (New Delhi, India), 21(1), 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R., Jaiswal, D., & Mishra, S. (2019). A model of customer loyalty: An empirical study of Indian retail banking customer. Global Business Review, 20(5), 1248–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, V. (2013). Service convenience, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Study of Indian commercial banks. Journal of Global Marketing, 26(1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, V., Durga Prasad, C. S., & Sharma, S. (2015). Service quality, service convenience, price and fairness, customer loyalty, and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(4), 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisidou, E., Sarigiannidis, L., Maditinos, D. I., & Thalassinos, E. I. (2013). Customer satisfaction, loyalty and financial performance: A holistic approach of the Greek banking sector. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 31(4), 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KFST. (2022). Konkurrencen på bankmarkedet for privatkunder. Available online: https://www.kfst.dk/media/vbunuwzv/20220809-konkurrencen-p%C3%A5-bankmarkedet-for-privatkunder.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Khatoon, S., Xu, Z., & Hussain, H. (2020). The mediating effect of customer satisfaction on the relationship between electronic banking service quality and customer purchase intention: Evidence from the Qatar banking sector. SAGE Open, 10(2), 215824402093588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, W. J., Santini, F. D. O., Sampaio, C. H., Perin, M. G., & Araújo, C. F. (2016). A meta-analysis of satisfaction in the banking sector. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(6), 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. (2009). Assessment of the psychometric properties of SERVQUAL in the Canadian banking industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 14(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-C., & Nguyen, N. L. (2018). Marketing strategy of internet-banking service based on perceptions of service quality in Vietnam. Electronic Commerce Research, 18(3), 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, R., & Kashiramka, S. (2023). Objectives of Islamic banking, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Empirical evidence from South Africa. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14(9), 2188–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, P., & Jaramillo, F. (2011). Ethical reputation and value received: Customer perceptions. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 29(5), 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (2010). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer: A behavioral perspective on the consumer (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoregie, O. K., Addae, J. A., Coffie, S., Ampong, G. O. A., & Ofori, K. S. (2019). Factors influencing consumer loyalty: Evidence from the Ghanaian retail banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(3), 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, C. N., & Yusuf, T. O. (2021). CSR: A roadmap towards customer loyalty. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(13–14), 1424–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, P., Suer, S., Keser, I. K., & Kocakoc, I. D. (2020). The effect of service quality and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty: The mediation of perceived value of services, corporate image, and corporate reputation. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(2), 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: Implications for further research. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V., Jaunky, V. C., Roopchund, R., & Oodit, H. S. (2021). ‘Customer satisfaction’, loyalty and ‘adoption’ of e-banking technology in Mauritius. In S. C. Satapathy, V. Bhateja, B. Janakiramaiah, & Y.-W. Chen (Eds.), Intelligent system design (Vol. 1171, pp. 885–897). Advances in intelligent systems and computing. Springer Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, H., Ennew, C., Kharouf, H., & Devlin, J. (2014). Trustworthiness and trust: Influences and implications. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(3–4), 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A., Banerjee, S., & Singh, B. (2023). The differential impact of e-service quality’s dimensions on trust and loyalty of retail bank customers in an emerging market. Services Marketing Quarterly, 44(2–3), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A., & Jebarajakirthy, C. (2019). The influence of e-banking service quality on customer loyalty: A moderated mediation approach. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(5), 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Sabol, B. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoana, M. C., Quaye, E. S., & Abratt, R. (2022). Antecedents of brand loyalty in South African retail banking. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 27(2), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Haq, I., & Awan, T. M. (2020). Impact of e-banking service quality on e-loyalty in pandemic times through interplay of e-satisfaction. Vilakshan—XIMB Journal of Management, 17(1/2), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Esterik-Plasmeijer, P. W. J., & van Raaij, W. F. (2017). Banking system trust, bank trust, and bank loyalty. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanniarajan, T., & Manimaran, S. (2008). Managing service quality in commercial banks: A gender focus. Asia-Pacific Business Review (New Delhi), 4(2), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V., & Raitani, S. (2014). Drivers of customers’ switching behaviour in Indian banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 32(4), 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | in % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 63.1 |

| Male | 36.9 |

| Age | |

| 18–29 years old | 38.6 |

| 30–49 years old | 27.0 |

| 40–49 years old | 15.4 |

| 50–59 years old | 22.7 |

| Over 60 years old | 11.7 |

| Personal annual income before tax | |

| DKK 199,999 or less | 32.7 |

| DKK 200,000–399,999 | 33.0 |

| DKK 400,000–599,999 | 19.8 |

| DKK 600,000–799,999 | 4.9 |

| DKK 800,000–999,999 | 1.6 |

| DKK 1 million or more | 1.3 |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to say | 6.7 |

| Construct | Standardized Factor Loading | Standard Error | t-Value | Construct Reliability | Extracted Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competent Personnel (ξ1) | 0.75 | 0.51 | |||

| X1: Personnel in the bank can help/guide me with the financial services I need | 0.731 | ||||

| X2: The bank’s advisers provide competent advice | 0.746 | 0.050 | 19.726 | ||

| X3: Personnel in the bank show respect and understanding for the customers | 0.654 | 0.048 | 18.274 | ||

| Bank Ethics and Reputation (ξ2) | 0.76 | 0.52 | |||

| X4: The bank has a good reputation/image | 0.734 | ||||

| X5: The bank is known for its high level of social responsibility | 0.695 | 0.052 | 18.738 | ||

| X6: The bank has high ethical standards, for example, not being involved in money laundering | 0.730 | 0.061 | 19.199 | ||

| Website (ξ3) | 0.82 | 0.60 | |||

| X7: The bank’s website is easy to navigate | 0.752 | ||||

| X8: The bank’s website is up-to-date and unproblematic | 0.861 | 0.049 | 24.392 | ||

| X9: The website of the bank is easy and clear | 0.707 | 0.045 | 22.117 | ||

| Security (ξ4) | 0.65 | 0.49 | |||

| X10: The bank handles personal information confidentially/safely | 0.574 | ||||

| X11: The security standard of the bank’s website is high | 0.801 | 0.125 | 13.484 | ||

| Convenient Location (ξ5) | 0.78 | 0.55 | |||

| X12: The bank is near my domicile | 0.807 | ||||

| X13: The bank is easily accessible from my workplace/study location | 0.783 | 0.047 | 19.646 | ||

| X14: The bank has branches easily accessible across almost the whole of Denmark | 0.596 | 0.042 | 17.501 | ||

| Interest Rates (ξ6) | 0.74 | 0.50 | |||

| X15: The rates of lending are among the lowest in the market | 0.836 | ||||

| X16: The rates of deposit are among the highest in the market | 0.511 | 0.041 | 14.076 | ||

| X17: It is possible to get a loan under good conditions | 0.677 | 0.049 | 16.522 | ||

| Switching barriers (ξ7) | 0.68 | 0.59 | |||

| X18: I believe that it will be pretty difficult for me to get used to being a customer in another bank than my current primary bank | 0.675 | ||||

| X19: I feel that I will waste the time I have spent familiarizing myself with my primary bank if I switch to another bank | 0.754 | 0.085 | 12.716 | ||

| Customer satisfaction (η1) | 0.79 | 0.56 | |||

| Y1: I am confident that my current primary bank meets my needs better than others | 0.740 | ||||

| Y2: How do you evaluate your primary bank in general, as compared to other banks in Denmark | 0.769 | 0.057 | 23.956 | ||

| Y3: How satisfied are you with your current primary bank | 0.735 | 0.043 | 22.976 | ||

| Customer loyalty (η2) | 0.79 | 0.55 | |||

| Y4: Have you ever considered choosing another bank as your primary bank in the past three years | 0.743 | ||||

| Y5: How likely is it for you that your current primary bank will continue to be your primary bank in the next five years | 0.790 | 0.032 | 24.766 | ||

| Y6: Even if my family or friends recommend switching to another bank, I will definitely choose to remain with my current bank | 0.688 | 0.037 | 21.736 |

| ξ1 | ξ2 | ξ3 | ξ4 | ξ5 | ξ6 | ξ7 | η1 | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ξ1 | 0.71 | ||||||||

| ξ2 | 0.41 | 0.72 | |||||||

| ξ3 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.77 | ||||||

| ξ4 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.70 | |||||

| ξ5 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.74 | ||||

| ξ6 | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.71 | |||

| ξ7 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.77 | ||

| η1 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.75 | |

| η2 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.74 |

| Hypotheses | Construct Regression Relationships | Std. Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Competent Personnel → Customer Satisfaction | 0.250 | 0.061 | 5.72 *** | Accept |

| H2 | Bank Ethics and Reputation → Customer Satisfaction | 0.104 | 0.048 | 2.49 * | Accept |

| H4 | Bank’s Website → Customer Satisfaction | 0.010 | 0.044 | 0.268 | Reject |

| H5 | Security → Customer Satisfaction | 0.055 | 0.035 | 1.17 | Reject |

| H7 | Convenient Location → Customer Satisfaction | −0.112 | 0.032 | −3.00 *** | Accept |

| H8 | Interest Rates → Customer Satisfaction | −0.119 | 0.036 | −2.56 *** | Accept |

| H9 | Interest Rates → Customer Loyalty | −0.165 | 0.032 | −5.84 *** | Accept |

| H10 | Customer Satisfaction → Customer Loyalty | 0.830 | 0.058 | 18.60 *** | Accept |

| H11 | Switching Barriers → Customer Loyalty | 0.163 | 0.038 | 4.749 *** | Accept |

| H12 | Switching Barriers → Customer Satisfaction | 0.423 | 0.039 | 9.127 *** | Accept |

| Hypotheses | Construct Correlation Relationships | Std. Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Decision |

| H3 | Competent Personnel ←→ Bank Ethics and Reputation | 0.418 | 0.016 | 9.25 *** | Accept |

| H6 | Security ←→ Bank’s Website | 0.375 | 0.018 | 12.49 *** | Accept |

| Modification indices | Convenient Location ←→ Switching barriers | 0.249 | 0.034 | 5.828 *** | Accept |

| Modification indices | Bank’s Website ←→ Convenient Location | 0.152 | 0.018 | 4.602 *** | Accept |

| Modification indices | Bank Ethics and Reputation ←→ Interest Rates | 0.362 | 0.024 | 8.534 *** | Accept |

| Modification indices | Competent Personnel ←→ Interest Rates | 0.381 | 0.020 | 8.979 *** | Accept |

| Explained proportion of construct variance | R2 | ||||

| Customer satisfaction | 0.248 | ||||

| Customer loyalty | 0.845 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Jensen, J.M.; Jørgensen, R.H. On the Factors Influencing Banking Satisfaction and Loyalty: Evidence from Denmark. Businesses 2025, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020026

Yang Y, Jensen JM, Jørgensen RH. On the Factors Influencing Banking Satisfaction and Loyalty: Evidence from Denmark. Businesses. 2025; 5(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yingkui, Jan Møller Jensen, and René Heiberg Jørgensen. 2025. "On the Factors Influencing Banking Satisfaction and Loyalty: Evidence from Denmark" Businesses 5, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020026

APA StyleYang, Y., Jensen, J. M., & Jørgensen, R. H. (2025). On the Factors Influencing Banking Satisfaction and Loyalty: Evidence from Denmark. Businesses, 5(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020026