Enhancing Restaurant Profits via Strategic Wine Sales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Flavor balancing and culinary matching: Effective pairings rely on balancing flavors and textures between food and wine. Techniques such as matching wine structure (e.g., acidity and mouthfeel) with food characteristics (e.g., fattiness, saltiness) can create harmonious dining experiences (N. Jackson, 2022; Klosse, 2011). For instance, fatty foods pair well with wines high in acidity, while bitter wines are complemented by rich, fatty dishes (Folly, 2021).

- (b)

- Molecular elements: This approach considered matches of foods and wines based on shared molecular components, such as anethole in fennel and certain wine aroma compounds. This method enhances sensory harmony, as complementary molecules amplify shared sensory perceptions (Chartiers, 2012).

- (c)

- Subjectivity and regional pairing: the tasters were also allowed to jointly decide on recommendations based on the subjective nature of taste and regional matches, such as pairing local wines with dishes from the same area. This approach leverages cultural familiarity to enhance customer comfort and enjoyment (Longuere, 2023).

3. Results

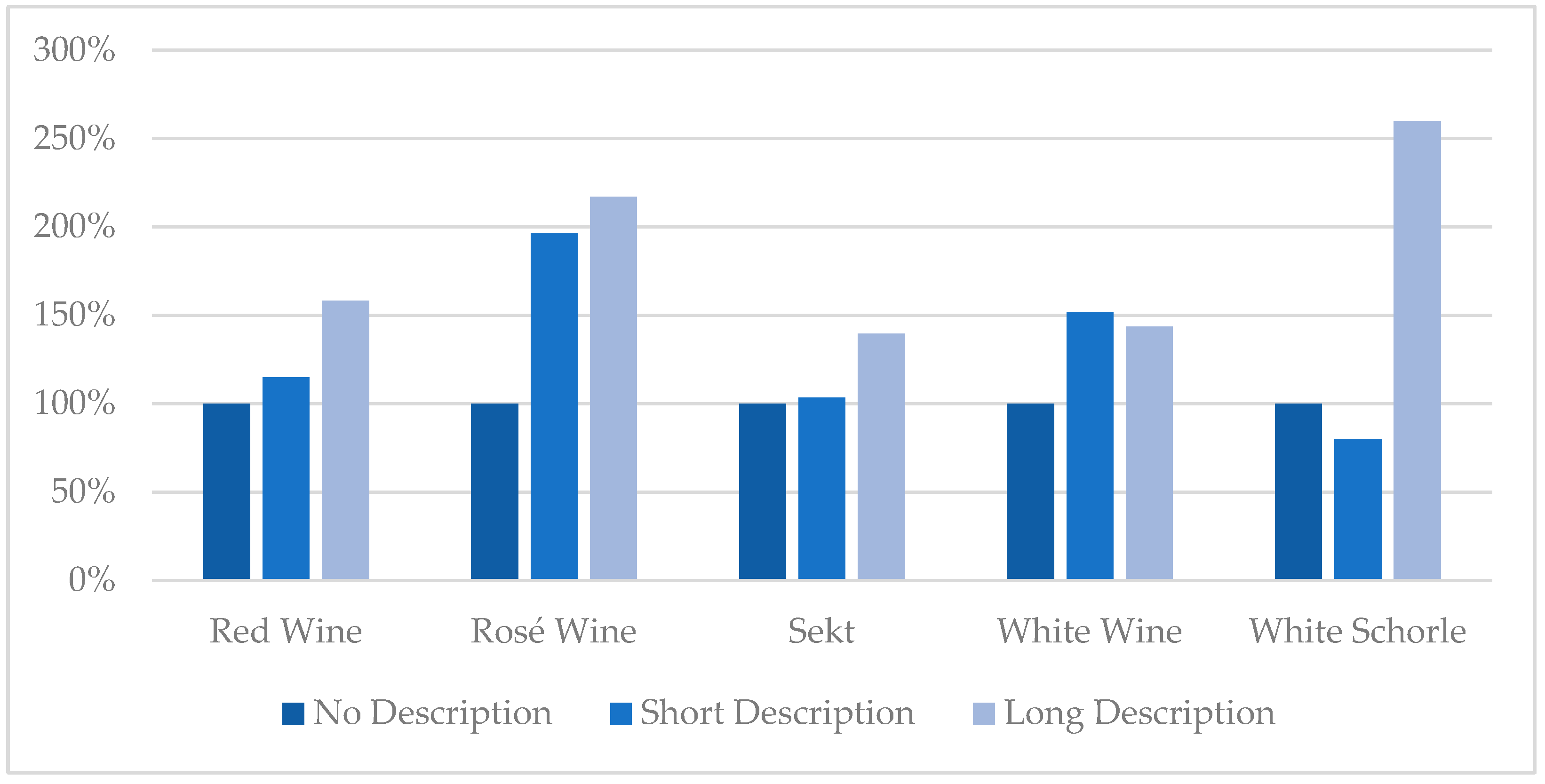

3.1. Impact of Wine Descriptions

3.2. Wine-and-Food Pairing Propositions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study Wine Description Examples for One Wine

Appendix B. Example Wine-and-Food Pairing

Appendix C. Example of a Wine Sensory Assessment

| Visual | Intensity—medium |

| Color—lemon | |

| Scent | Intensity—medium+ |

| Aromas—Flint, Quince, TDN, Citrus, Nuts | |

| Taste | Flavors—Slate, Unripe Yellow Nectarine |

| Sweetness—dry | |

| Acidity—medium+ | |

| Tannin Level—none | |

| Overall Nature—green | |

| Alcohol—medium | |

| Body—medium | |

| Flavor Intensity—medium | |

| Finish—medium | |

| Other—slight petillance |

Appendix D. Comprehensive Data Sheet: Wine Orders

| No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine Style | Wine Style Description | # Bills with Wine Ordered | # Individual Wine Orders | Total Wine Orders | # Bills with Wine Ordered | # Individual Wine Orders | Total Wine Orders | Wine Orders | # Bills with Wine Ordered | % Increase Compared to No Description | # Individual Wine Orders | % Increase compared to No Description |

| Red | ||||||||||||

| Red | No Description | 149 | 203 | EUR 3860 | 0 | 0 | - | EUR 3860 | 149 | 203 | ||

| Red | Short | 21 | 22 | EUR 586 | 142 | 195 | EUR 3842 | EUR 4428 | 163 | 8.59% | 217 | 6.45% |

| Red | Long | 11 | 19 | EUR 796 | 192 | 255 | EUR 5306 | EUR 6102 | 203 | 26.60% | 274 | 25.91% |

| Red | Total | 181 | 244 | EUR 5241 | 334 | 450 | EUR 9148 | EUR 14,389 | 515 | 694 | ||

| Rosé | ||||||||||||

| Rosé | No Description | 11 | 11 | EUR 218 | 0 | 0 | - | EUR 218 | 11 | 11 | ||

| Rosé | Short | 3 | 3 | EUR 29 | 26 | 24 | EUR 399 | EUR 428 | 29 | 62.07% | 27 | 59.26% |

| Rosé | Long | 3 | 5 | EUR 71 | 23 | 25 | EUR 402 | EUR 473 | 26 | 57.69% | 30 | 63.33% |

| Rosé | Total | 17 | 19 | EUR 318 | 49 | 49 | EUR 801 | EUR 1119 | 66 | 68 | ||

| Sekt | ||||||||||||

| Sekt | No Description | 89 | 178 | EUR 2035 | 0 | 0 | - | EUR 2035 | 89 | 178 | ||

| Sekt | Short | 15 | 22 | EUR 311 | 94 | 191 | EUR 1792 | EUR 2103 | 109 | 18.35% | 213 | 16.43% |

| Sekt | Long | 8 | 16 | EUR 145 | 112 | 231 | EUR 2697 | EUR 2842 | 120 | 25.83% | 247 | 27.94% |

| Sekt | Total | 112 | 216 | EUR 2491 | 206 | 422 | EUR 4489 | EUR 6980 | 318 | 638 | ||

| White | ||||||||||||

| White | No Description | 166 | 236 | EUR 3502 | 0 | 0 | - | EUR 3502 | 166 | 236 | ||

| White | Short | 23 | 29 | EUR 348 | 193 | 252 | EUR 4970 | EUR 5318 | 216 | 23.15% | 281 | 16.01% |

| White | Long | 12 | 13 | EUR 299 | 193 | 255 | EUR 4732 | EUR 5031 | 205 | 19.02% | 268 | 11.94% |

| White | Total | 201 | 278 | EUR 4149 | 386 | 507 | EUR 9702 | EUR 13,850 | 587 | 785 | ||

| White Schorle | ||||||||||||

| White Schorle | No Description | 2 | 5 | EUR 28 | 0 | 0 | €- | EUR 28 | 2 | 5 | ||

| White Schorle | Short | - | 2 | 4 | EUR 22 | EUR 22 | 2 | 0.00% | 4 | −25.00% | ||

| White Schorle | Long | - | 6 | 13 | EUR 72 | EUR 72 | 6 | 66.67% | 13 | 61.54% | ||

| White Schorle | Total | 2 | 5 | EUR 28 | 8 | 17 | EUR 94 | EUR 121 | 10 | 22 | ||

References

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “Lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanisms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A. D., Bressan, A., O’Shea, M., & Krajsic, V. (2015). Perceived benefits and challenges to wine tourism involvement: An international perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(1), 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areni, C. S., & Kim, D. (1993). The influence of background music on shopping behavior: Classical versus top-forty music in a wine store. ACR North American Advances, 20, 336–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, R. H. (2011). Improving experts’ wine quality judgements: Two heads are better than one. Journal of Wine Economics, 6(02), 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas-Cejudo, A., Iruretagoyena, M., Alonso, L., Church, M., Izquierdo, L., Hill, I., & Larson, K. (2025). Gastronomy and beyond: A collaborative initiative for rethinking food’s role in society, sustainability, and territory. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 39, 101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, C. W. (1996). Evaluating the profit potentials of restaurant wine lists. Journal of Restaurant & Foodservice Marketing, 1(3–4), 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, J. J. (2011). A model for wine list and wine inventory yield management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(3), 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfratello, L., Piacenza, M., & Sacchetto, S. (2009). Taste or reputation: What drives market prices in the wine industry? Applied Economics, 41(17), 2197–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, G., Gil, I., & Ruiz, M. E. (2009). Do upscale restaurant owners use wine lists as a differentiation strategy? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, E., & Cruz, M. (2021). Can business model innovation help SMEs in the food and beverage industry to respond to crises? Findings from a Swiss brewery during COVID-19. British Food Journal, 123, 3638–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J., & Alant, K. (2009). The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 21(3), 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J., Saliba, A., & Miller, B. (2018). Consumer engagement in the wine choice process: The role of wine knowledge. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 30(31), 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, E. T., Canziani, B., Hsieh, Y.-C. J., Debbage, K., & Sonmez, S. (2016). Wine tourism: Motivating visitors through core and supplementary services. Tourism Management, 52, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriota, S., Curzi, D., & Delmastro, M. (2013). Tasters’ bias in wine guides’ quality evaluations. Applied Economics Letters, 20(12), 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriota, S., & Delmastro, M. (2012). Seller reputation: Individual, collective, and institutional factors. Journal of Wine Economics, 7(01), 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celhay, F., Flocher, P., & Cohen, J. (2013, April 7–11). Decoding wine label design: A study of Bordeaux Grand Crus visual codes. 7th International Conference, St. Catherines, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S., & Menival, D. (2011). Wine tourism in champagne. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(1), 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S., & Pettigrew, S. (2005). Is wine consumption an aesthetic experience? Journal of Wine Research, 16, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartiers, F. (2012). Taste buds and molecules. In The art and science of food, wine and flavor. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cichetti, D. V. (2010). On the reliability and accuracy of wine tasting: Designing the experiment. American Association of Wine Economists. [Google Scholar]

- Costanigro, M., McCluskey, J. J., & Goemans, C. (2010). The economics of nested names: Name Specificity, reputations, and price premia [article]. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 92(5), 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, S., & Pecotich, A. (2013). Evaluation of wines by expert and novice consumers in the presence of variations in quality, brand and country origin cues. Food Quality and Preferences, 28, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N., & Charters, S. (2006, July 6–8). Building restaurant wine lists: A study in conflict. 3rd International Wine Business Research Conference, Montpellier, France. [Google Scholar]

- De Albuquerque Meneguel, C. R., Mundet, L., & Aulet, S. (2019). The role of a high-quality restaurant in stimulating the creation and development of gastronomy tourism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T. H. (1997). Techniques to increase impulse wine purchases in a restaurant setting. Journal of Restaurant & Foodservice Marketing, 2(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M. (2014). Strategic winery management and tourism: Value-added offerings and strategies beyond product centrism. In L. Kyuho (Ed.), Strategic winery tourism and management: Building competitive winery tourism and winery management strategy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M. (2017). Strategic profiling and the value of wine & tourism initiatives: Exploring strategic grouping of German wineries. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 29(4), 484–502. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M., & Paunovíc, I. (2021). Business model innovation: Strategic expansion of German small and medium wineries into hospitality and tourism. Administrative Sciences, 11(4), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, P., & Nauges, C. (2010). Identifying the effect of unobserved quality and experts’ reviews in pricing of experience goods: Empirical application on bordeaux wine. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 28, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folly, W. (2021). Flavor balancing and food pairing basics. Wine Folly Blog. Available online: https://winefolly.com (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Gawel, R., Oberholster, A., & Francis, I. L. (2000). A ‘Mouth-feel Wheel’: Terminology for communicating the mouth-feel characteristics of red wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research, 6(3), 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergaud, O., & Livat, F. (2004). Team versus individual reputations: A model of interaction and some empirical evidence (Post-Print and Working Papers). Université Paris1 Panthéon-Sorbonne halshs-03280777, HAL. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03280777 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Getz, D., & Brown, G. (2006). Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tourism Management, 27(1), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, I., Berenguer, G., & Ruiz, M. E. (2009). Wine list engineering: Categorization of food and beverage outlets. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokcekus, O., & Nottebaum, D. (2011). The buyer’s dilemma: To whose rating should a wine drinker pay attention? AAWE working paper 91. Available online: https://wine-economics.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/AAWE_WP91.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Gómez-Carmona, D., Paramio, A., Cruces-Montes, S., Marín-Dueñas, P. P., Montero, A. A., & Romero-Moreno, A. (2023). The effect of the wine tourism experience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 29, 100793. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, R., Velikova, N., & Dodd, T. (2009). The importance of wine recommendations in consumer decision making. Journal of Wine Research, 20(23), 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, T. P., Hore, P. J., & Chauhan, S. (2006). The effect of mood on perception of wine taste. Food Quality and Preference, 17, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R. S., & von Clef, J. (2001). The influence of verbal labeling on the perception of odors: Evidence for olfactory illusions? Perception, 30(3), 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, R. T. (2009). How expert are “expert” wine judges? Journal of Wine Economics, 4(02), 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, J. (2003). Expectations and the food industry: The impact of color and appearance. Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ileri-Gurel, E., Schuler, B. R., & Maurer, M. (2013). Stress. mood, and food choices: Implications for quality of life. Appetite, 65, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanović, S., Galičić, V., & Pretula, M. (2008, May 7–9). Gastronomy as a science in the tourism and hospitality industry. 19th Biennial International Congress Tourism and Hospitality Industry 2008 New Trends in Tourism and Hospitality Management (pp. 561–569), Opatija, Croatia. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, N. (2022). Beyond flavor. In Wine tasting by structure (2nd ed.). Independently Published. ISBN-10:1709965703. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R. S. (2009). Wine tasting: A professional handbook. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, W. Y. (2015). Marketing strategies for profitability in small independent restaurants [Ph.D. thesis, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., & Bruwer, J. (2007). Regional brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 19(4), 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. R., Gawel, R., Francis, I. L., & Waters, E. J. (2008). The influence of interactions between major white wine components on the aroma. flavor, and texture of model white wine. Food Quality and Preference, 19, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, D. (2024). U.S. restaurant and food service industry data reveals economic and workforce data. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241215153710/https://www.onfocus.news/u-s-restaurant-and-food-service-industry-data-reveals-economic-and-workforce-data/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Klosse, P. (2011). Food and wine pairing: A new approach. Research in Hospitality Management, 1(1), 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koch, J., Martin, A., & Nash, R. (2013). Overview of perceptions of German wine tourism from the winery perspective. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 25(1), 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, S., Bruwer, J., & Li, E. (2009). The role of perceived risk in wine purchase decisions in restaurants. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 21(2), 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, C. (2014). The cultivation of taste: Chefs and the organization of fine dining. OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Livat, F., & Remaud, H. (2018). Factors affecting wine price mark-up in restaurants. Journal of Wine Economics, 13(2), 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livat, F., Remaud, H., & McHale, A. (2023). The puzzle of wine price in restaurants. Wine Business Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longuere, L. (2023). Wine pairing principles: Enhancing the dining experience. Le Cordon Bleu Insights. Available online: https://cordonbleu.edu (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Maberly, C., & Reid, D. (2014). Gastronomy: An approach to studying food. Nutrition & Food Science, 44(4), 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- Manescu, S., Frasnelli, J., Lepore, F., & Djordjevic, J. (2014). Now you like me, now you don’t: Impact of labels on odor perception. Chemical Senses, 39(2), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Lajara, B., Martínez-Falcó, J., Millan-Tudela, L. A., & Sánchez-García, E. (2023). Analysis of the structure of scientific knowledge on wine tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon, 9(2), e13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, E., Bruwer, J., & Li, E. (2009). Region of origin and its importance among choice factors in the wine-buying decision making of consumers. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 21(3), 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, R., Brito, C., Lopes, B., & Correia, R. (2023). Satisfaction and dissatisfaction in wine tourism: A user-generated content analysis. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 25, 14673584231191989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menival, D., & Han, H. Y. (2013, June 12–15). Wine tourism: Futures sales and cultural context of consumption. 7th International Conference AWBR, St. Catherines, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Dols, J., & González-Pernía, J. L. (2020). Gastronomy as a real agent of social change. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 21, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestlé. (2011). So is(s)t deutschland—Ein spiegel der gesellschaft. D. Fachverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, A. C. (1987). The wine aroma wheel. University of California. [Google Scholar]

- North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1997). In-store music affects product choice. Nature, 390, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1999). The influence of in-store music on wine selections. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, I. M., Gustafsson, I.-B., & Johansson, L. (2002). Wine and food interaction: Consumer perceptions. Food Service Technology, 2(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nygren, I. M., Gustafsson, I.-B., & Johansson, L. (2003). Effect of taste familiarity on wine and food matching. Food Service Technology, 3(4), 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pangborn, R. M., Berg, H. W., & Hansen, B. (1963). The influence of color on discrimination of sweetness in dry table-wine. American Journal of Psychology, 76, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preszler, T., & Schmit, T. M. (2009). Factors affecting wine purchase decisions and presence of eco-labels. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 38(31), 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Radjenovic, M. (2014). Development model of the fine dining restaurant. Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija. Biennial International Congress. Tourism & Hospitality Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Salvat, J., & Boqué, J. B. (2008). New opportunities and challenges in wine tourism. Available online: http://www.pct-turisme.cat/intranet/sites/default/files/URV_project_salvat_blay_seminar_pctto.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Santos, V. R., Ramos, P., Almeida, N., & Santos-Pavón, E. (2019). Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 11(6), 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamel, G. (2009). Dynamic analysis of brand and regional reputation: The case of wine. Journal of Wine Economics, 4(01), 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segelbaum, E. (2022). The new financials of running a restaurant wine program. Available online: https://daily.sevenfifty.com/the-new-financials-of-running-a-restaurant-wine-program/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Shepherd, G. M. (2017). Neuroenology. In How the brain creates the taste of wine. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, A. M. (2000). Napa Valley, California: A model of wine region development. In B. Cambourne, M. Niki, C. M. Hall, & L. Sharples (Eds.), Wine tourism around the world, development management and markets (pp. 283–296). Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Sogari, G., Menozzi, D., & Mora, C. (2018). Sensory-liking expectations and perceptions of processed and unprocessed insect products. International Journal on Food System Dynamics, 9(4), 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. (2017). Gastrophysics: The new science of eating. Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C., Velasco, C., & Knoeferle, K. (2014). A large sample study on the influence of the multisensory environment on the wine drinking experience. Flavor, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P. (2023). Exploring the sensory synergy of gastronomy: A comprehensive review of contemporary trends and practices in food and wine pairing. International Journal for Multidimensional Research Perspectives, 1(3), 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. (2024). Food and beverage service industry’s number of employees in European countries 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1459209/number-of-employees-food-beverage-services-europe-by-country/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Staub, C., & Siegrist, M. (2022). Rethinking the wine list: Restaurant customers’ preference for listing wines according to wine style. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 34(3), 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, L., & Siegrist, M. (2022). The role of flavor profiles in wine menu design: Improving customer satisfaction. Food Quality and Preference, 95, 104367. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D. C., Russen, M., Dawson, M., & Reynolds, D. (2024). Defining and establishing a restaurant wine culture. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(6), 1926–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpitz, K. (2024). Gastrosterben—Fast jeder vierte Gastronom überlegt aufzugeben. HB online. Available online: https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/handel-konsumgueter/insolvenzen-fast-jeder-vierte-gastronom-ueberlegt-aufzugeben/100053205.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Terrier, L., & Jaquinet, A.-L. (2016). Menu design and customer choices: How providing information about wine pairings can enhance the dining experience. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 58, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B., Quintal, V., & Phau, I. (2010, November 29–December 1). A research proposal to explore the factors influencing wine tourist satisfaction. Proceedings of Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, M., & Casella, E. (2017). The role of field experiments in generating replicable results for organizational improvement. Journal of Business Research, 74, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Veseth, M. (2015). Money, taste, and wine: It’s complicated! Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Wansink, B., Cordua, G., Blair, E., Payne, C., & Geiger, S. (2006). Wine promotions in restaurants: Do beverage sales contribute or cannibalize? Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47(4), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, J. A., & McCluskey, J. J. (2005). Collective reputation and quality. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(1), 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J., & Oshinsky, N. S. (1966). Food names and acceptability. Journal of Advertising Research, 6(1), 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zak, P., Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Zellner, D. A., & Durlach, P. (2003). Effect of color on expected and experienced refreshment. intensity, and liking of beverages. American Journal of Psychology, 116, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wine Sales | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Totals | Revenue (EUR) | Wine% of Total Revenue | |

| # Days | 111 | ||

| # Bills | 1086 | 194,075 | |

| Total Wine Orders (includes multiple wines on one bill) | 1496 | 36,459 | 19% |

| Wine List Description Style | Red (EUR) | Rosé (EUR) | Sekt (EUR) | White (EUR) | White Schorle (EUR) | Wine Sales (EUR) Total by Wine List Description | Wine Sales (%) Total by Wine List Description | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Description | 3860 | 26.8% | 218 | 19.5% | 2035 | 29.2% | 3502 | 25.3% | 28 | 22.7% | 9642 | 26.4% |

| Short Description | 4428 | 30.8% | 428 | 38.2% | 2103 | 30.1% | 5318 | 38.4% | 22 | 18.2% | 12,298 | 33.7% |

| Long Description | 6102 | 42.4% | 473 | 42.3% | 2842 | 40.7% | 5031 | 36.3% | 72 | 59.1% | 14,519 | 39.8% |

| Total | 14,389 | 1119 | 6980 | 13,850 | 121 | 36,459 | ||||||

| Red | Rosé | Sekt | White | White Schorle | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | No Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation | Wine–Food Pairing Recommendation on Menu | Total | |

| No Description | 149 | 0 | 149 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 89 | 0 | 89 | 166 | 0 | 166 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Short Description | 21 | 142 | 163 | 3 | 26 | 29 | 15 | 94 | 109 | 23 | 193 | 216 | 2 | 2 | |

| Long Description | 181 | 334 | 515 | 3 | 23 | 26 | 8 | 112 | 120 | 12 | 193 | 205 | 6 | 6 | |

| Total | 181 | 334 | 515 | 17 | 49 | 66 | 112 | 206 | 318 | 201 | 386 | 587 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 35.15% | 64.85% | 25.76% | 74.24% | 35.22% | 64.78% | 34.24% | 65.76% | 20.00% | 80.00% | ||||||

| Daily Average Wine Ordered with Food Pairing Recommendation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Days | % of Study Days | Daily Average % of Wine Sales | Average Increase in Wine Sales % with Recommendation | |

| Days without Recommendation | 42 | 37.8% | 34% | |

| Days with Recommendation | 69 | 62.2% | 67% | |

| Total | 111 | |||

| % Difference | 60.9% | 50.4% | 10.5% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheridan, S.; Dressler, M. Enhancing Restaurant Profits via Strategic Wine Sales. Businesses 2025, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020024

Sheridan S, Dressler M. Enhancing Restaurant Profits via Strategic Wine Sales. Businesses. 2025; 5(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheridan, Scott, and Marc Dressler. 2025. "Enhancing Restaurant Profits via Strategic Wine Sales" Businesses 5, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020024

APA StyleSheridan, S., & Dressler, M. (2025). Enhancing Restaurant Profits via Strategic Wine Sales. Businesses, 5(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5020024