1. Introduction

In today’s competitive world, organizations face new difficulties in maintaining efficiency and creating a committed workforce (

Andavar & Ali, 2020, p. 29). Committed employees tend to be more determined in their work and exhibit high efficiency and productivity. Accordingly, organizational commitment explains an employee’s involvement with a particular organization (

Asbari et al., 2019, p. 206).

Each employee needs to be committed to the company’s goals and objectives, perform their duties effectively as a member of the team, and realize organizational objectives (

Chanana, 2021). Employees who have high organizational commitment are employees who are more productive and stable, making them more profitable for the organization (

Imelda et al., 2020, p. 2383).

The success of an organization must be seen by obtaining competent employees and maintaining them to work in the organization. This can be performed by ensuring there is gratification and eagerness at work, as well as the desire to endure work and display total devotion to the organization. This will likely give a positive image to the organizational commitment because it will be understood as one of the approaches to attain a company’s objectives (

Keyvanlo et al., 2020) and (

Muoghalu & Tantua, 2021, p. 89).

Therefore, it is not surprising that organizational commitment as a concept has been extensively explored in the literature for decades and is defined as a concept related to the employee and several variables that enable the employee to contribute, stay, and maintain commitment to the company (

Rameshkumar, 2020, p. 105) and (

Setiawan et al., 2020). Moreover, the importance of organizational commitment stems from the generally accepted notion that an employee with a strong commitment to the organization will be productive and will always support it (

Tindowen, 2019, p. 617).

Despite the extensive research on organizational commitment, there is a notable lack of empirical studies investigating the dynamics of organizational commitment among employees in provincial government departments, particularly in the context of South Africa. Specifically, the relationship between demographic factors (age, gender, and tenure) and organizational commitment remains understudied. The current study aims to fill this knowledge gap by exploring the perceptions of employees in the North West Provincial Department regarding their level of commitment.

Organizational commitment remains a critical issue within contemporary organizational management. Prior studies extensively examined organizational commitment (OC) and identified its correlation with productivity and employee retention (

Rameshkumar, 2020, p. 105) and (

Yao et al., 2019, p. 1).

However, little empirical research explicitly addresses how demographic factors such as age, gender, and tenure influence organizational commitment, particularly within the context of provincial government departments. This study uniquely contributes by filling this gap, examining employees from the Office of the Premier in North West Province, South Africa. Understanding these demographic influences provides managers with strategic insights to enhance employee engagement and retention.

2. Definition of Concepts

2.1. Organizational Commitment (OC)

Organizational commitment is considered an emotional and psychological dependence on an organization. Subsequently, a person who is strongly committed and engages in it may enjoy membership in the organization (

Yao et al., 2019). According to

Kotzé and Nel (

2020, p. 524), organizational commitment refers to an attitude or psychological condition that characterizes the relationships between employees and their employers, which ultimately influences their intentions to stay or leave the organization.

Furthermore,

Setiawan et al. (

2020, p. 2383) explain organizational commitment as the extent to which an employee will experience a sense of community within their organization and as a condition of employees who support certain organizations and their goals, as well as their intention to maintain membership in the company.

2.2. Employee Commitment (EC)

Employee commitment designates the aspiration of an employee to share the beliefs and aims of the organization, in addition to working toward the attainment and achievement of organizational success amidst rivals (

Pathak & Pandey, 2019, p. 58).

Muoghalu and Tantua (

2021) clarify employee commitment as a sign that employees are satisfied with their employers’ expectations and when organizations meet the expectations of their employees. Understandably, this will spur them to develop a commitment to the organization.

2.3. Affective Commitment (AC)

Affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional attachment to their organization. Employees with high affective commitment stay with the organization because they want to do so. Employees with higher affective commitment exhibit better performance (

Karem et al., 2019, p. 2395). Affective commitment is also understood as an employee’s constructive emotional bonding to the organization; such an employee strongly associates with organizational goals and seeks to stay because they wish to do so (

Anwar & Abdullah, 2021).

Abdullah (

2019, p. 439) describes affective commitment as employees’ feelings towards joining the organization, continuous commitment as employees’ perceptions of the costs of leaving the organization, and normative commitment as employees’ perceptions of their duties and promises towards the organization.

According to

Abdullah and Othman (

2021, p. 179), affective commitment refers to individuals who remain in their organizations with a solid commitment and hold their position because they require the occupation. Similarly,

Anwar and Abdullah (

2021, p. 5) explain affective commitment as an employee of a business who will often identify strongly with the company and its objectives and who might reject offers to move to a new company, even if they seem more financially attractive.

2.4. Normative Commitment (NC)

McCormick and Donohue (

2019, p. 2581). describe normative commitment as that shown by individuals who are perceived to remain at the firm out of obligation, often referred to as an “obligation to stay”, which also has a relationship with “moral obligation”. Often, the application in real conditions is related to personal motivation as a natural bond to the organization. Specifically, it is connected to individual values that view loyalty as the most important factor in working.

Researchers indicate that normative commitment refers to the meaning and importance of employees in an organization. This describes workers who have significant regulatory involvement and appear to feel that they should remain in the business. Due to this commitment, they will be held to their job by normative commitment, which would be made concrete by work ethics (

Choudhury, 2020, p. 157) and (

Jamal et al., 2021, p. 293).

2.5. Continuance Commitment (CC)

Additionally,

Kartika and Pienata (

2020) indicate that continuance commitment arises from an employee’s desire to survive in an organization for security reasons. Employees are urged to remain because of their inability to work outside the organization. The longer employees remain in the organization, the more they worry about losing what they have invested in the organization while being members of it.

Karem et al. (

2019, p. 2395) view continuance commitment as an employee’s awareness of the cost associated with leaving the organization; employees with continuance commitment remain with the organization because they feel that they must continue because of the financial advantages.

3. Literature Review

3.1. An Overview of Organizational Commitment

Several researchers have studied the connection between employees and their employing organizations and have established that employees are the dynamic force of every organization (

Albalawi et al., 2019, p. 310). Employees’ organizational commitment is one of the most significant organizational challenges because employees do not maintain the same commitment as they had before (

Q. I. Khan et al., 2021, p. 465).

Organizational commitment can be regarded as an individual’s identification and participation within a specific organization (

Vasconcelos, 2020, p. 413). It reflects an individual’s psychological state, which refers to the employees’ organization and defines a relationship between the employee and organization (

Y. Zhang et al., 2019, p.1296).

Penni (

2019) argues that organizational commitment is an important part of the psychological condition of employees, including their attitudes towards their organization. The most common technique for dealing with organizational commitment is to improve an organization’s emotional requirements (

J. Zhang et al., 2019, p. 811).

3.2. Employee Commitment

Several studies have confirmed that organizations with strong ethical values are more likely to benefit from having more committed employees (

Qing et al., 2020, p. 1405) and (

Grabowski et al., 2019, p. 193). Employees’ commitment to an organization increases or decreases depending on their interpersonal relations with leaders, the environment of the workgroup, and the opportunities for improvement (

Qing et al., 2020, p. 1405). In other words, employees’ lack of commitment to the company may influence their intention to leave and, consequently, their turnover rates (

Dai et al., 2019, p. 69). Most importantly, employees can often make things work, even without a very good system, and are the key to higher productivity in organizations (

Brown & Harvey, 2011).

Gulzar (

2020, p. 1440) specifies that employees who are committed to their organizations are more likely to be better performers than those who are less committed because they exercise more effort on behalf of the organization towards success and strive to achieve its goals and missions.

Paramita et al. (

2020, p. 273) explains that employees with higher commitment scores are expected to be more motivated and perform at the highest level.

Paramita et al. (

2020, p. 273) generalized research examining employee commitment and concluded that high employee commitment is created by harmony between the organizational environment and personal factors. Organizational environmental factors are related to people, work conditions, and the work environment.

Several researchers have revealed that committed employees are regarded as a foundation of organizational performance and efficiency, which in turn boosts organizational effectiveness and productivity (

Maiti et al., 2021, p. 716). Employees’ organizational commitment is one of the attitudes that could lead to high performance (

Paramita et al., 2020, p. 273).

3.3. The Three-Component Model of Commitment

One of the most widely used theories of organizational commitment is

Allen and Meyer’s (

1990, p. 1) three-component model (

Somers et al., 2019, p. 649). The components are affective commitment, that is, emotional connection to the organization; continuance commitment, that is, perceived costs associated with leaving the organization; and normative commitment, that is, feeling obligated towards the organization (

Somers et al., 2019, p. 649).

Although each commitment profile represents a relationship between an organization and an employee, these relationships differ in nature. Whilst there are differences in nature between these commitments’ profiles, the multidimensional nature of each profile also “integrates attitudinal and behavioral approaches” (

Meyer et al., 2021).

3.4. Affective Commitment

Affective commitment is defined as an emotional attachment to the organization, a devotion to performing the tasks, and the desire to stay in the organization (

Yang et al., 2020, p. 129). According to

Somers et al. (

2019, p. 649), employees with this type of commitment have an emotional connection with the organization.

Haider et al. (

2019, p. 129) believe that affective commitment is employees’ dependence on the organization under emotional belonging, which is the same as organizational goals and values.

Wang et al. (

2020, p. 609) show that such individuals are psychologically and emotionally dedicated and experience meaning in their work and congruence between their own goals and values and the organization’s.

Mensah and Bawole (

2020, p. 479) reveal that affective commitment is related to employee outcomes, such as productivity, attendance, and retention. Furthermore,

Wirawan et al. (

2020, p. 1139) indicate that affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional attachment, identification, and involvement with the organization.

According to

Wang et al. (

2020, p. 609), an employee with a strong affective commitment will work enthusiastically, making any effort toward the success of the organization.

Wang et al. (

2020, p. 609) further assert that this commitment occurs when employees commit to their employing organization because they are satisfied and feel a sense of belonging at the organization. They maintain that it essentially expresses the emotional attachment of employees to their organization, their desire to see the organization succeed in its goals, and a feeling of pride in being a part of that organization.

Employees with a higher degree of emotional commitment are more likely to continue working for the organization voluntarily and eagerly because they feel integrated within the organization and have internalized its norms and values as their own (

Kuklenski, 2021, p. 87). Affective commitment (AC) is determined by an employee’s personal choice to remain committed to the organization through emotional identification with the organization (

Al-Jabari & Ghazzawi, 2019).

3.5. Normative Commitment

Normative commitment in the field of management has been described as an obligation to remain in a particular organization (

Somers et al., 2019, p. 649). According to

Somers et al. (

2019, p. 649), employees with this kind of commitment have a strong feeling of duty towards the organization. Therefore, we surmise that normative commitment is an attachment based on perceived obligation as well as a sense of duty or loyalty.

Oh (

2019, p. 88) indicates that this type of commitment refers to the organizational commitment that occurs when employees fully believe in the organization; it is also called a moral commitment. However,

A. J. Khan and Iqbal (

2020, p. 88) explain that it is a commitment based on a sense of obligation to the organization, and employees with a strong normative commitment survive because they think they must do so.

Grego-Planer (

2020, p. 1150) specifies that in normative commitment, the staff regard continuing their job and providing services for the organization as their duties, thereby fulfilling their responsibilities in the organization and feeling obligated to stay with the organization because of pressure from others or the belief that it is morally correct to do so (

A. J. Khan & Iqbal, 2020, p. 88). This reveals a feeling of compulsion to continue employment (

Grego-Planer, 2020, p. 1150).

3.6. Continuance Commitment

Many researchers indicate that continuance commitment (i.e., perceived costs associated with leaving the organization) refers to the material benefits gained from being with the organization and the costs associated with leaving the organization; the more investment in the staff, the lower the possibility for the staff to leave the organization (

Lambert et al., 2020).

Continuance commitment refers to an individual’s argument to remain based on the high cost associated with leaving the organization and the perceived loss of sunken costs (

Gabay-Mariani & Adam, 2020, p. 147). This is related to the need to remain in the organization due to the perceived costs associated with leaving. Contrarily, when the staff work for a long duration in the organization, they are unlikely to easily leave the organization and will continue their job because of necessity (

Aguinis, 2023).

Rameshkumar (

2020, p. 105) indicates that continuance commitment derives from a worker’s perception of the costs associated with leaving an organization, causing them to stay out of necessity. Employees with strong continuance commitment continue to work in their organizations because they need to (

Rameshkumar, 2020, p. 105).

According to

Reeves et al. (

2021), continuance commitment results from the motivation to avoid impending costs linked to a possible change in employer. Employees’ commitment is higher when they perceive the costs of such a change, namely, relocation costs, wage losses, or loss of personal contact with former colleagues, to be greater (

Reeves et al., 2021).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

A descriptive research design was utilized through a questionnaire to gather employees’ views on key concepts relating to the impact of career orientation on organizational commitment and performance.

Thanavathi (

2021, p. 6972) describes a descriptive research approach as a theory-based pattern mode fashioned by gathering, analyzing, and presenting serene data. This allows researchers to gain insights into why and how research has been conducted.

Participants

The target population for this study was from a provincial government department in North West, ranging from subordinates to senior management. The sample comprised 300 employees. Accordingly, 300 questionnaires were distributed. However, out of 300 questionnaires, only 214 were correctly completed and returned.

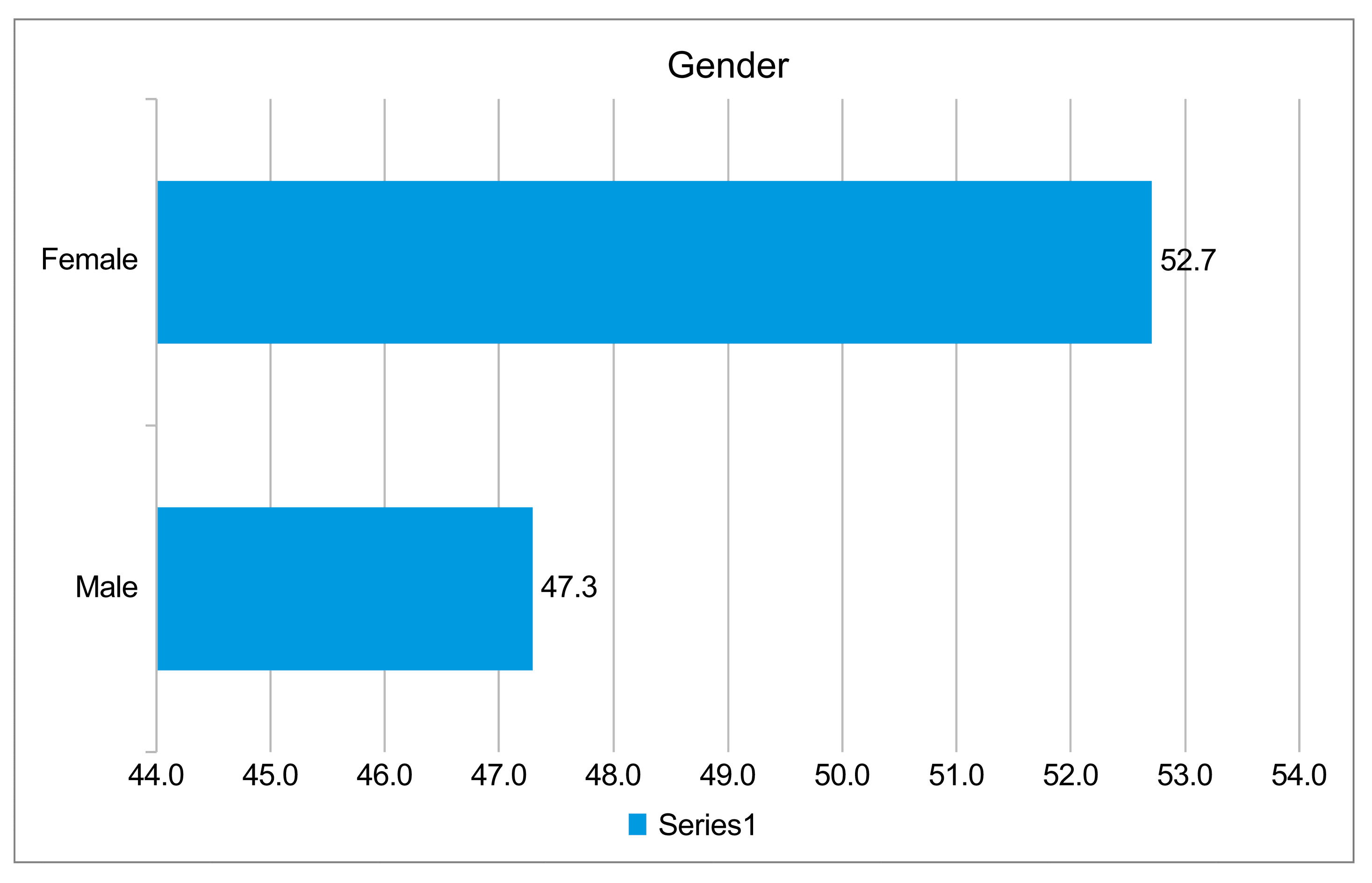

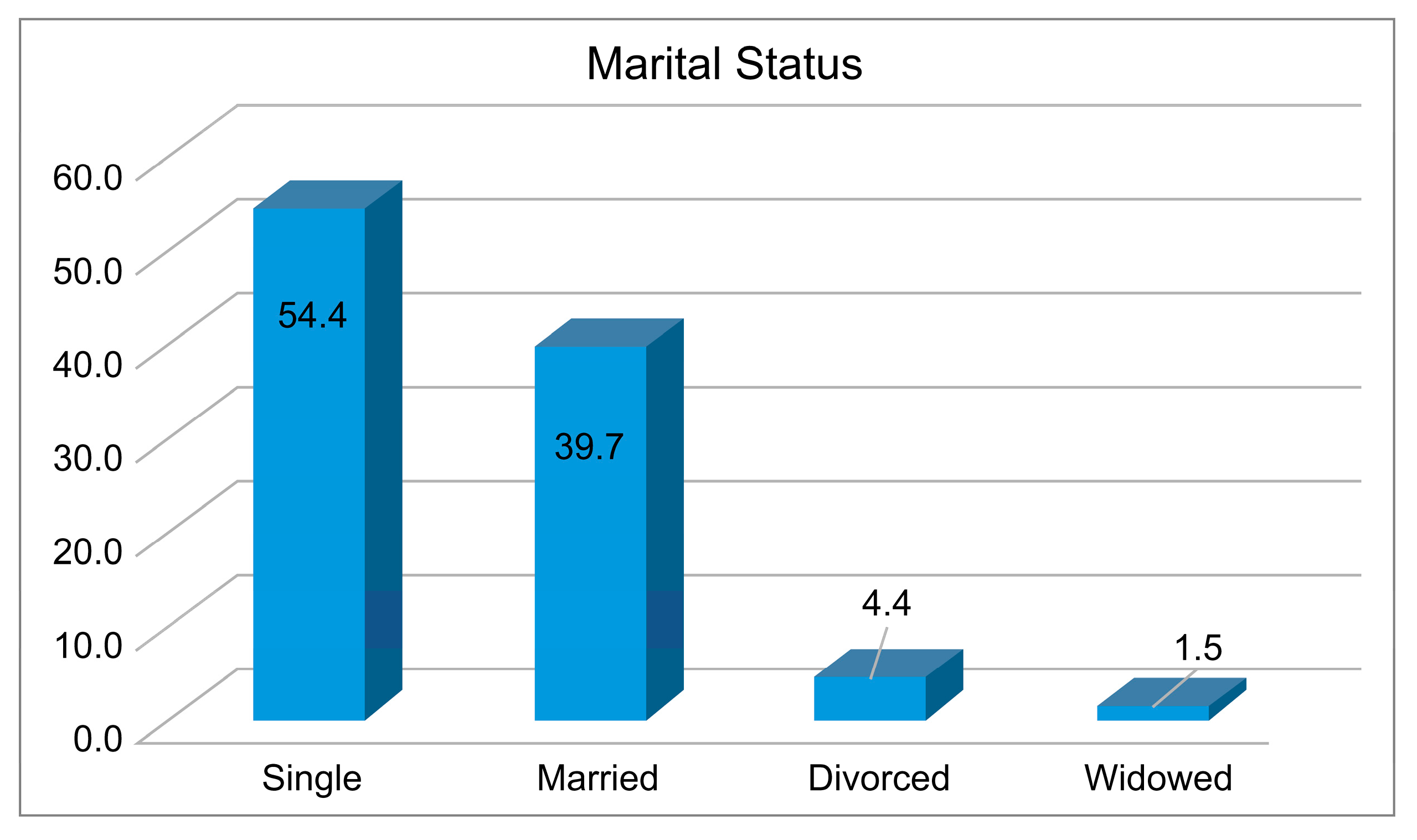

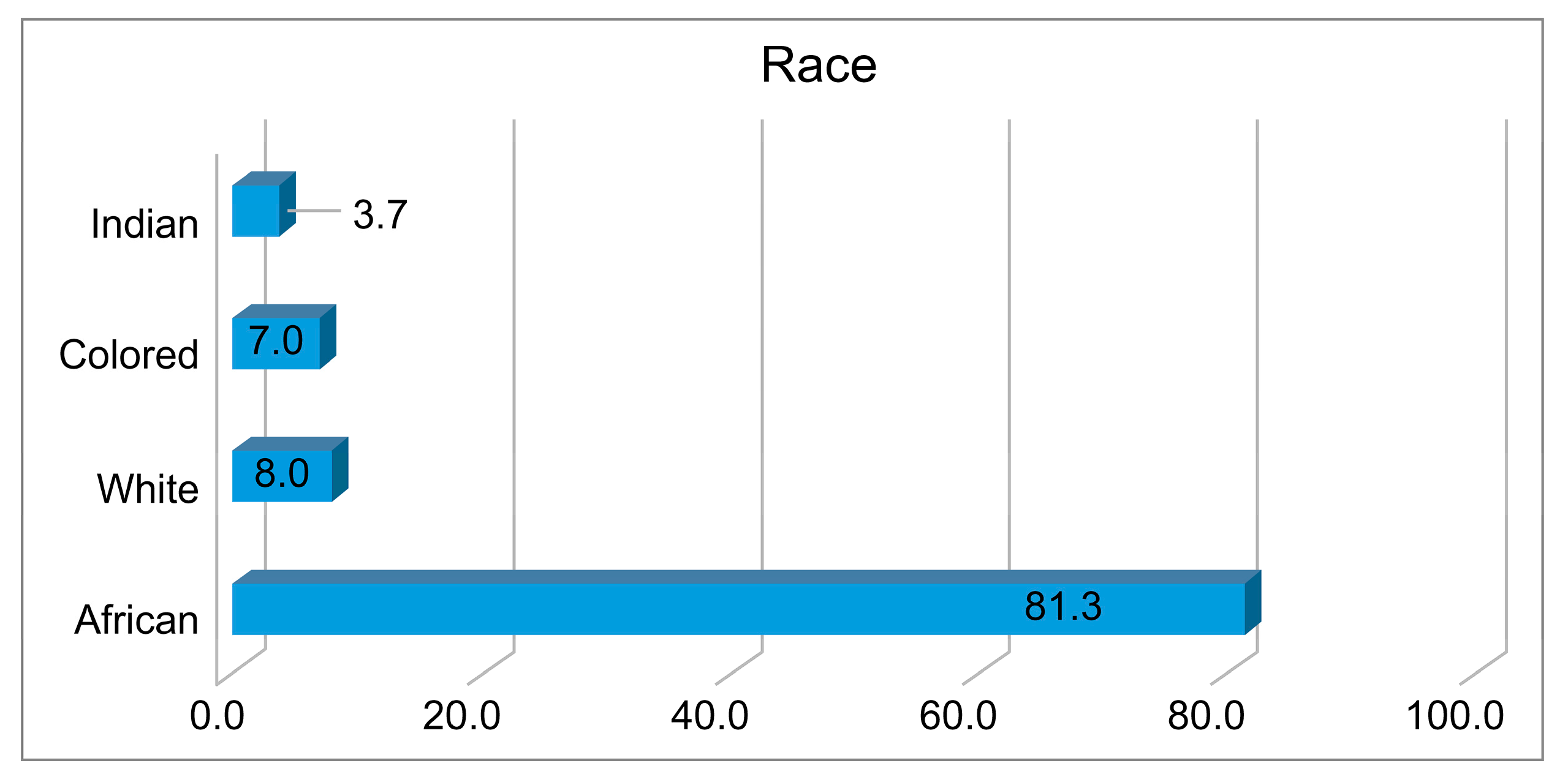

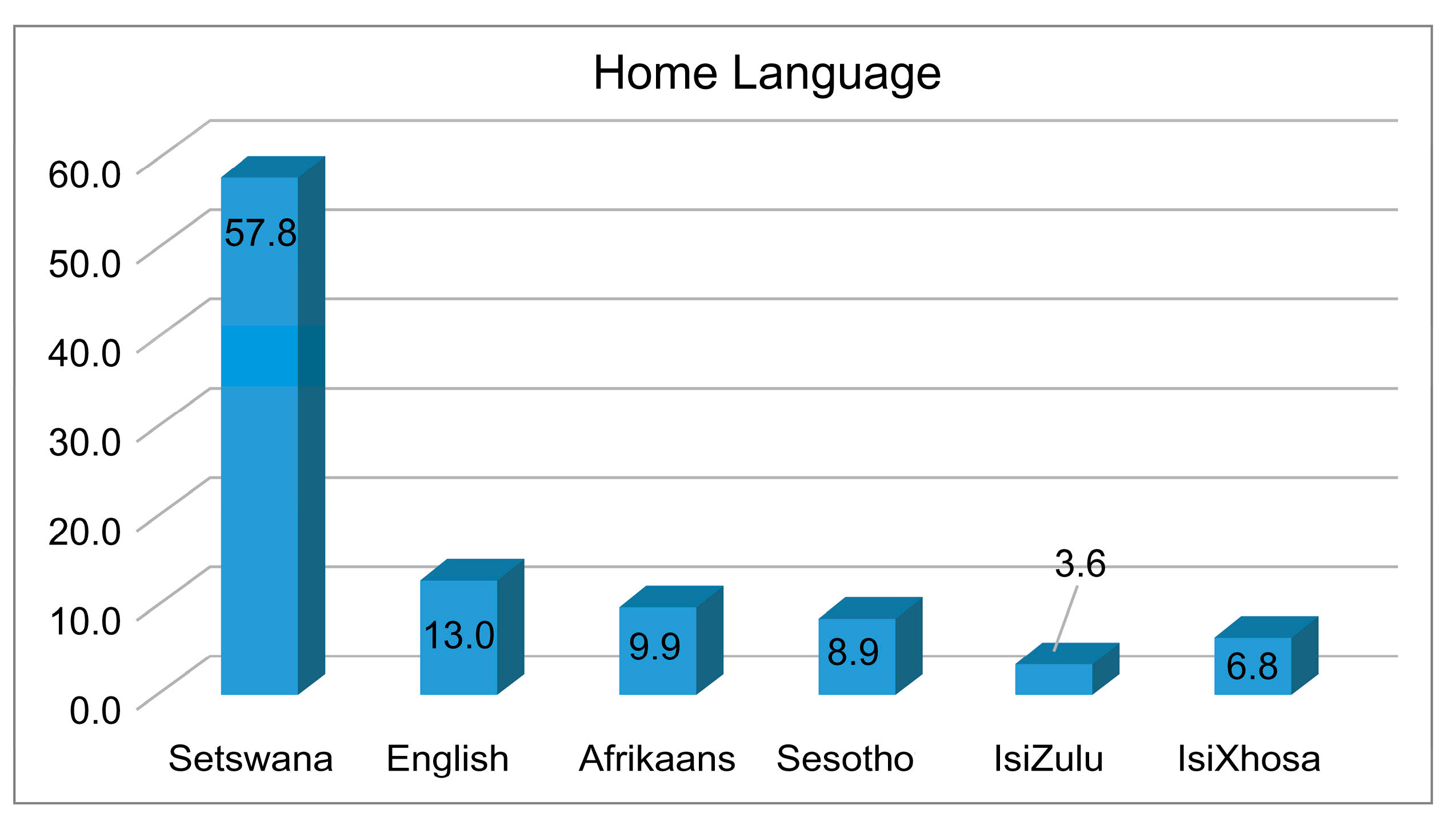

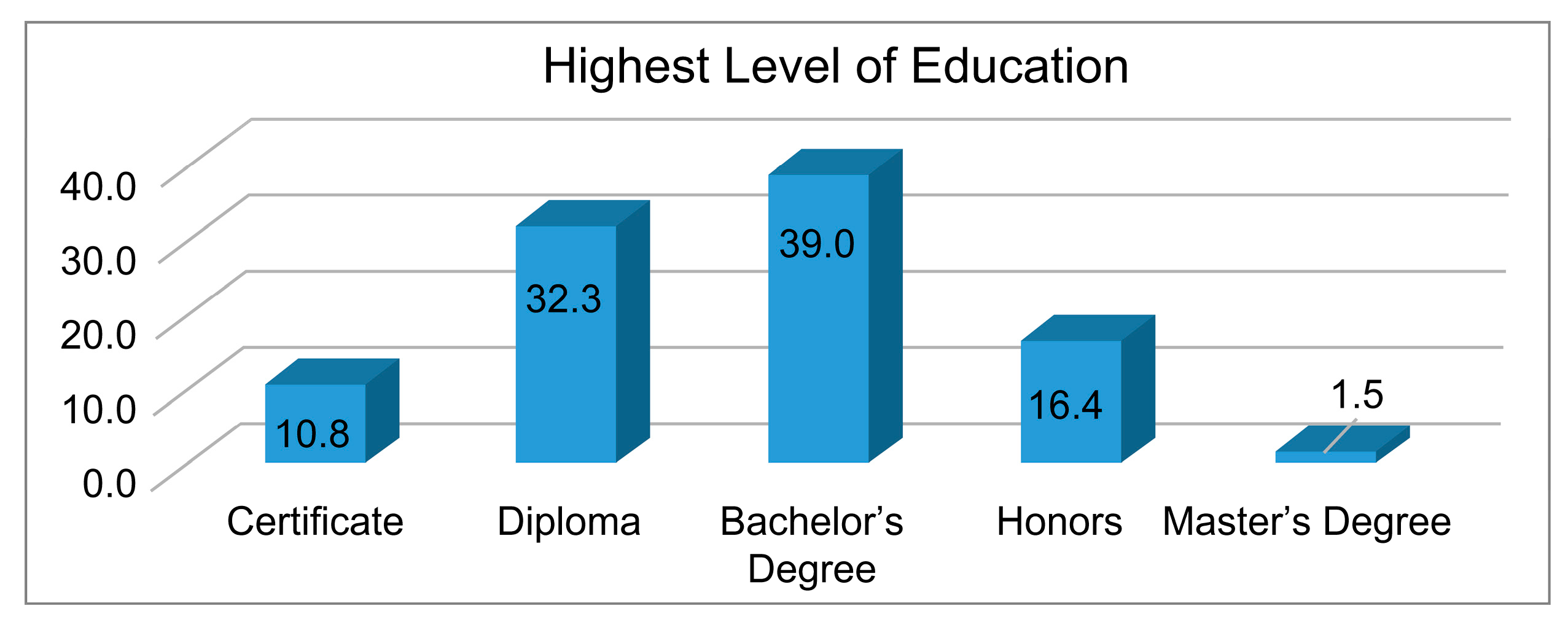

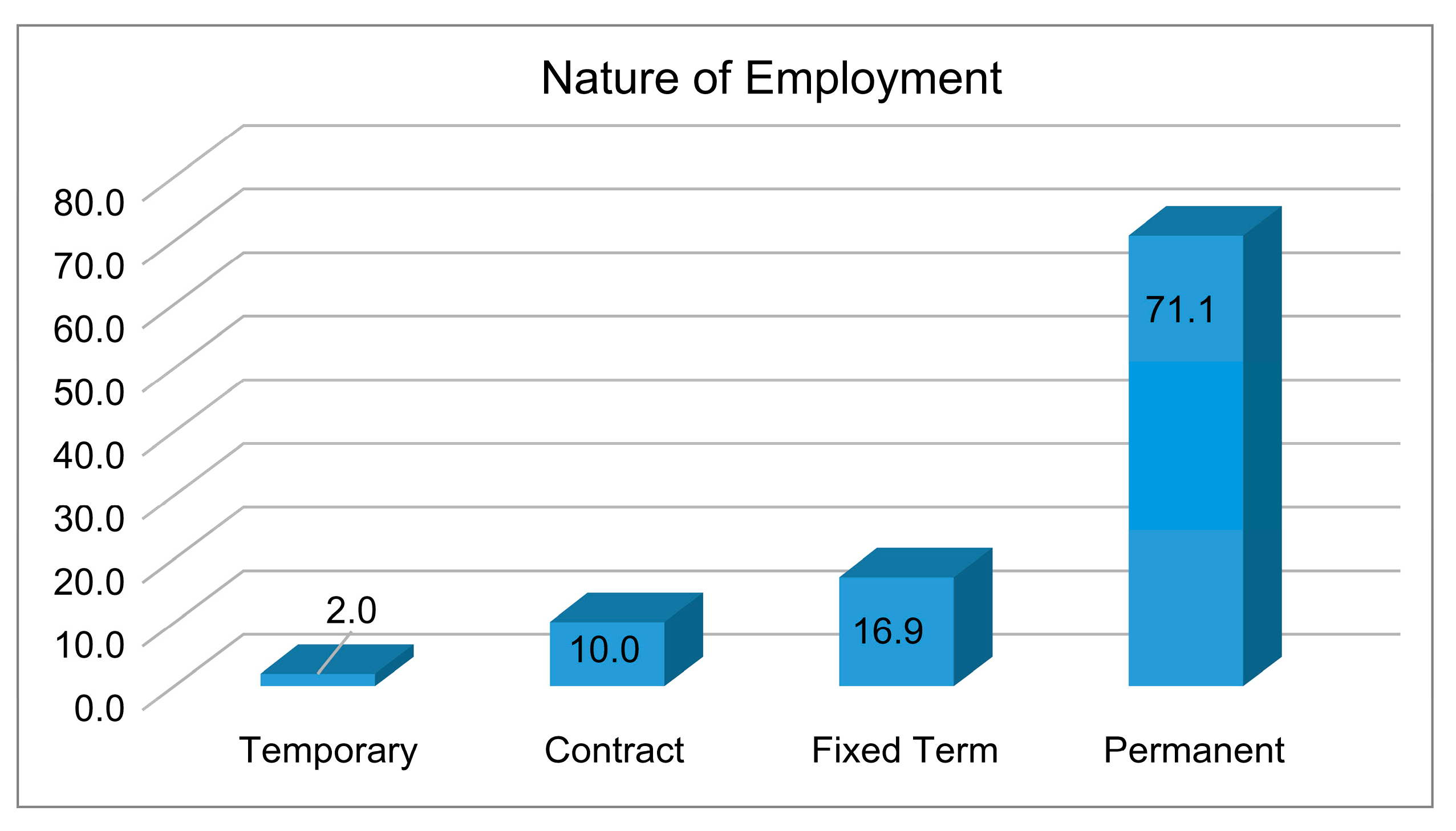

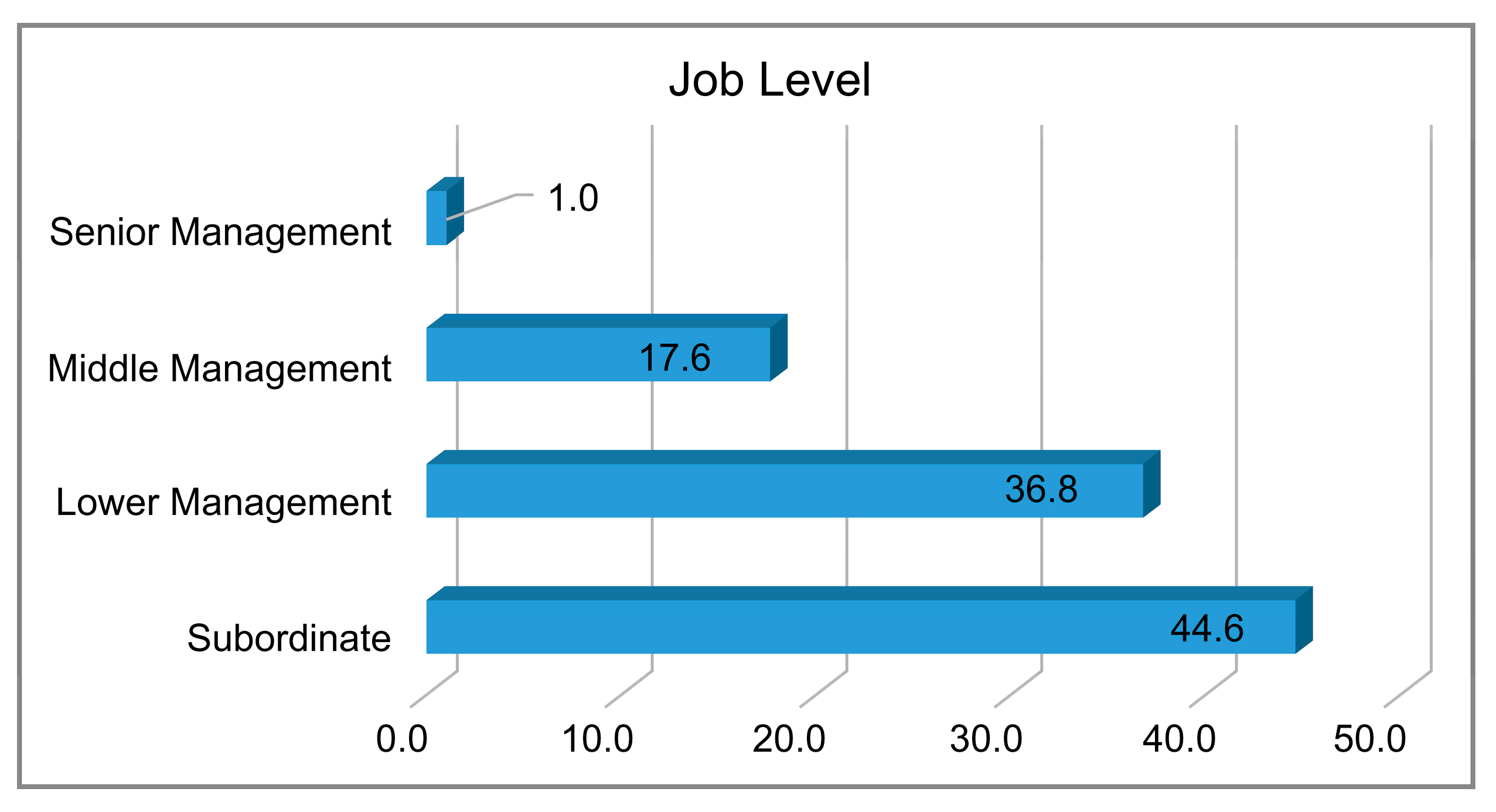

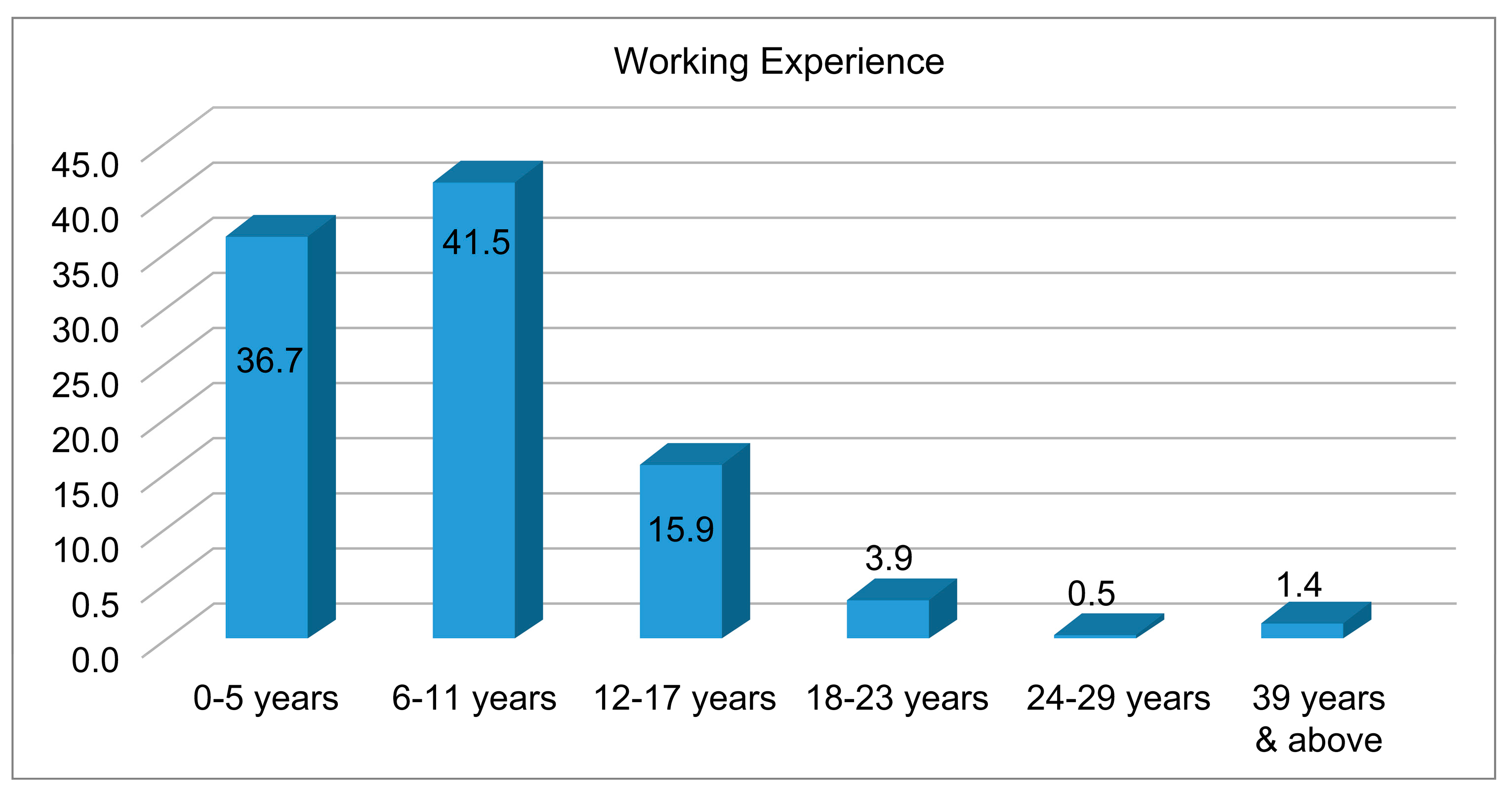

A total of 214 employees participated in this study. Among respondents, females constituted a slight majority (52.7%) compared to males (47.3%). Most respondents were single (54.4%), African (81.3%), and predominantly Setswana speakers (57.8%), reflecting regional demographics. The majority were permanent employees (71.1%), held subordinate positions (44.6%), possessed bachelor’s degrees (39%), and had working experience primarily between 6 to 11 years (41.5%). The demographic statistics of the respondents are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 below, providing clear summaries and graphical presentations for enhanced clarity and accessibility to demographic information.

Figure 1 shows that most respondents were female (52.7%), while males accounted for only 47.3%.

As shown in

Figure 2, respondents were asked to indicate their marital status; most (54.4%) were single, followed by 39.7% being married, and only 4.4% being divorced. Finally, only 1.5% of the respondents indicated that they were widowed.

Figure 3 indicates that most (81.3%) respondents were Africans, followed by 8% being White. Around 7% of the respondents were colored, with only 3.7% being Indian.

Figure 4 shows that the majority (57.8%) of employees of the North West provincial department (Office of the Premier) who responded were Setswana-speaking people, followed by those who speak English (13%), Afrikaans (9.9%), Sesotho (8.9%), IsiXhosa (6.8%), and IsiZulu (3.6%). This shows that most respondents were Setswana speakers. This finding was not surprising because the North West province is predominantly Setswana-speaking.

Figure 5 indicates that the majority (42.3%) of the respondents’ ages ranged from 6 to 30 years, followed by 6% of those who were between the ages of 31 to 35 and 41 to 45, respectively. Approximately 5% of respondents were between the ages of 36 and 40, followed by 2% of those who were between the ages of 46 and 50 and less than 25, respectively. Finally, only 1% of respondents indicated that they were above 51 years of age.

Figure 6 shows that most respondents (39%) obtained a bachelor’s degree, 32.3% held a diploma, followed by 16.4% who had honors degrees, and 10% who had certificates. Only 1.5% of respondents had a master’s degree.

Figure 7 shows that most (71.1%) of the respondents were permanent employees, followed by 16.9% who were fixed-term employees. Approximately 10% of the employees were contractual. Finally, only 2% were temporarily employed.

Figure 8 shows that the majority (44.6%) of the respondents worked as subordinates, followed by 36.8% who worked as lower management. Around 17.6% occupied middle management positions, while 1% occupied senior management positions.

Figure 9 indicates that the majority (41.5%) of the respondents’ work experience was between six and 11 years, followed by 36.7% who had work experience between zero and five years. Around 15.9% of respondents had work experience between 12 and 17 years, followed by 3.9% who had work experience between 18 and 23 years and 3.9% who had work experience of 30 years and above. Finally, only 0.5% of respondents indicated that they had work experience of between 24 and 29 years.

Figure 10 indicates that the majority (56.1%) of the respondents were promoted after one to three years, followed by 30.7% who were not promoted since joining the organization.

Approximately 10.6% of the respondents were promoted after four to six years. Finally, only 2.6% of respondents were promoted after seven to nine years.

4.2. Research Procedure

The researcher was granted ethical clearance and permission to distribute the questionnaires through a formal letter from the university. A request letter was sent to the North West Provincial Department, which was subsequently approved by the Head of Human Resources. Questionnaires were administered from office to office with clear explanations, and participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Measuring Instrument

In terms of the measuring instrument, an Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) was used to collect data on how accurate the items were for participants. Items such as “One of the major reasons I continue working for this department is that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice and even if it were to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave”, were graded by allocating numbers from 1 to 4; that is, strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), and strongly agree (4).

4.3. Statistical Analysis

This section analyzes the data obtained by the questionnaires distributed to the employees, who range from subordinates to senior management. The analysis was performed using descriptive statistics to describe the demographic variables of the participants. Descriptive statistics were also used to measure the effects of career orientation on the organizational commitment and performance of the North West Provincial Department (Office of the Premier). The overall scores of individual items on the affective commitment scale were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Table 1 presents the mean scores on each of the items as well as the standard deviation.

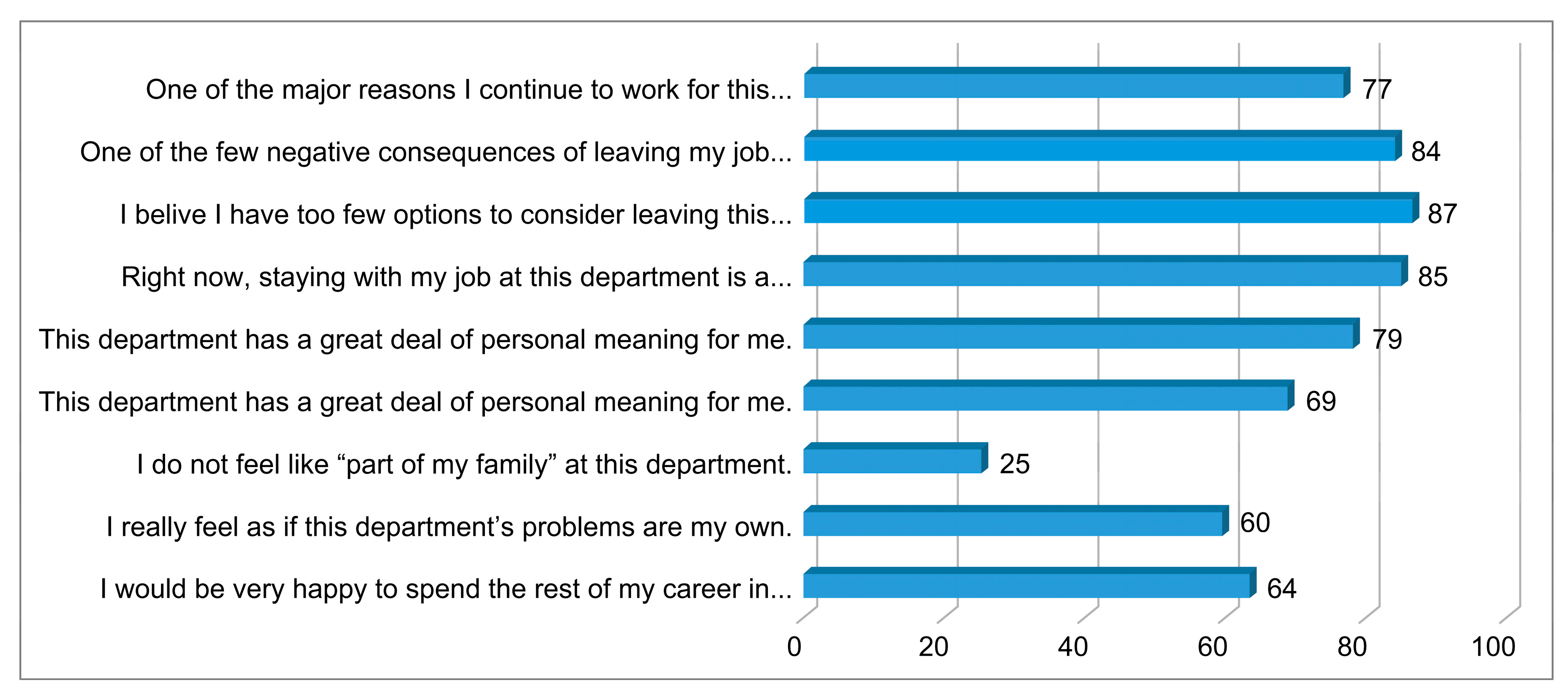

In the scores presented in

Table 1, a low score indicates disagreement (1), and a high score indicates agreement (4). The scores on the affective commitment scale are high according to the data presented in

Table 1. Another approach used in the current study was to present the results graphically to examine the percentage of respondents who agreed (3 and 4 on the scale) with each statement.

Figure 11 shows the percentage of agreement for each statement. Based on the data presented, 77% of the respondents agreed that one of the major reasons they continued working for their department was that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice, while 84% agreed that one of the few negative consequences of leaving their jobs in this department was the scarcity of available alternatives elsewhere.

The majority (87%) of the respondents agreed that they believed they had too few options to consider leaving their current department; 85% indicated that remaining with their jobs in their current department was a matter of necessity as much as desire; 79% agreed that their current department had significant personal meaning for them; 25% agreed that they did not feel like “part of my family” at this department; 60% agreed that they really felt their department’s problems were their own; and 64% agreed that they would be very happy to spend the rest of their careers in this department.

Table 2 indicates the overall score on affective organizational commitment, the different age groups significantly differ, as the

p-value is greater than 0.05 (

p = 0.003). Furthermore, there were some differences in individual items, including the following:

Right now, staying with my job at this department is a matter of necessity as much as desire (p = 0.009): Respondents older than 55 to 64 would be significantly more likely to be “staying with my job at this department is a matter of necessity as much as desire”.

One of the few negative consequences of leaving my job in this department would be the scarcity of available alternatives elsewhere (p = 0.046): Younger respondents aged 25–34 were least likely to associate with the company’s problem.

This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me (p = 0.034): As with the company’s problems, the younger respondents of 25–34 years did not view the organization as having much personal meaning for them.

One of the major reasons I continue to work for this department is that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice (p = 0.017): As with the company’s problems, the younger respondents of 20–29 years did not view the organization as having much personal meaning for them.

Table 3 shows a comparison of males and females regarding the affective organizational commitment items and total scale score. The mean scores were presented graphically, and the differences were tested for significance using a

t-test for independent measures.

The

t-test information is presented in

Table 4, which presents some differences between male and female responses. The significant differences relate to the question, “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career in this department (

p = 0.021). It appears females are less likely to discuss the organization than men. For example, this is how the females scored on the statement: This department has a great deal of personal meaning for me (

p = 0.001). It also appears that women are less likely to see the organization’s problems as their own. This is reflected in their response to the following statement: One of the major reasons I continue to work for this department is that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice (

p = 0.035).

5. Results

This study discovered that, in terms of age and organizational commitment, most older employees demonstrate a positive relationship with organizational commitment. This is supported by the findings of

Elkhdr and Aimer (

2020) and

Gasengayire and Ngatuni (

2019, p. 1), who indicated that older employees are more committed to the organization and report significantly higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment than their younger counterparts.

Furthermore, younger employees can leave the organization at any time because of future job opportunities.

Malik (

2020, p. 3272) indicated that such employees are not committed, reliable, or even loyal to the organization, unlike older employees who have invested much in the organization, with their turnover intention fading with the years of job tenure.

Based on experience and organizational commitment, this study established that older employees who have remained in the job for a long time are more likely to be better committed to the organization than newer and younger employees. According to

Roberts-Lombard (

2020, p. 1851), the benefits of older employees include increased experience, professionalism, work ethics, and knowledge, and lower turnover. This provides a significant advantage for organizations in terms of increasing organizational performance and effectiveness.

In terms of gender and organizational commitment, the present study revealed that females were less likely to discuss the organization compared to men, who seemed more forthcoming when asked about the organization. Interestingly, most respondents were female (52.7%), while males accounted for only 47.3%. Therefore, this finding reflects the complexity of gender dynamics as far as openness about organizations is concerned. Similarly,

Memon et al. (

2019, p. 2408) found that women felt it was inappropriate to talk in public.

Overall, the respondents indicated that the department held a great deal of personal meaning for them. However, women were less likely to see the organization’s problems as their own, which was reflected in their response to the following statement: “One of the major reasons I continue to work for this department is that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice”. Thus, it also appears that women are less likely to see an organization’s problems as their own.

This is supported by

Peterson et al. (

2019, p. 389), who found that organizational commitment was higher among men than among women in four countries (Australia, China, Hungary, and Jamaica) and higher among women than among men in two countries (Bulgaria and Romania).

Research Results Based on Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1. Younger employees (aged 25–34) demonstrate higher affective commitment due to emotional attachment.

Results supported this hypothesis. Respondents aged 25–34 significantly identified emotionally with their organization, indicating it held considerable personal meaning for them (p = 0.034).

Hypothesis 2. Older employees (aged 55–64) exhibit greater continuance commitment due to fewer employment alternatives.

Results affirmed this hypothesis. Employees aged 55–64 reported significantly higher continuance commitment, reflecting necessity-driven attachment to their current positions due to limited alternatives (p = 0.009).

Hypothesis 3. Female employees are less likely to openly discuss organizational problems than male employees.

Results validated this hypothesis. Female respondents were significantly less inclined to discuss their organization openly compared to their male counterparts (p = 0.021).

6. Discussion

This study revealed that most respondents (77%) agreed that one of the primary reasons they continued to work for their department was that leaving would require considerable personal sacrifice. Additionally, this study showed that 84% of respondents agreed that one of the few negative consequences of leaving their jobs in their respective departments would be the scarcity of available alternatives elsewhere. When employees work for a long time in an organization, they will not easily leave because of their needs (

Aguinis, 2023).

The majority (87%) of respondents indicated that they believed that they had limited job options outside their current department. Furthermore, 85% of respondents stayed due to necessity. Interestingly, 75% of the respondents found personal meaning in their work.

Wang et al. (

2020, p. 609) confirm that such individuals are psychologically and emotionally dedicated and that they experience meaning in their work and congruence between their own goals and values and the organization’s.

The demographic differences in employee commitment are also noteworthy. Younger respondents (25–34) were emotionally attached to the organization and felt a sense of personal meaning. This is supported by

Soenanta et al. (

2020), who indicated that affective commitment is an employee’s emotional attachment to their organization and feeling themselves to be a part of their organization. Thus, they will remain in the organization because they like it (

Nguyen & Khoa, 2020, p. 495).

The current study’s findings resonate with previous research, demonstrating that younger employees’ emotional attachment aligns with the affective commitment model proposed by

Somers et al. (

2019, p. 649). Similarly, older employees’ necessity-based attachment confirms the continuance commitment articulated by

Otuohere (

2021, p. 114), highlighting perceived scarcity of alternative employment opportunities.

Older respondents (55–64) stayed due to necessity and fear of limited alternative job opportunities. The gender differences observed align with

Memon et al. (

2019, p. 2408), who noted similar disparities in openness and emotional connection to organizational challenges. These results underscore demographic variables’ significance, aligning with the previous literature yet offering new empirical insights specific to government organizations.

6.1. Recommendations

It is recommended that, during recruitment and selection processes, human resource practitioners consider candidates aged between 25 and 34 since they are healthy potential future employees of the organization. In terms of their responses, 64% agreed that they would be very happy to spend the rest of their careers in the department. They associated with the company’s problems and indicated that the organization had great personal meaning for them.

Birhane (

2021) asserted that recruitment involves selectivity in staffing to ensure the right employees are selected for the organization and that this involves extensive and intensive processes of recruitment and selection according to predetermined and standardized methods and techniques.

Based on this study’s findings, it is further recommended that older and experienced employees (55–64) be used for internal training and development. Armed with experience, they can sharpen the knowledge and skills of the employees aged 25–34. Additionally, effective training programs can lead to greater commitment and lower employee costs because training is a tool that can assist organizations in building a more committed and productive workforce. This is important because training and development are crucial strategic tools for the effective improvement of individual and organizational performance.

The findings showed that younger respondents aged 25–34 years did not view the organization as having much personal meaning for them. Therefore, this study recommends that the organization motivate and encourage this group to have a different picture of their workplace so they are more committed to it and remain longer. Motivated employees tended to be more and feel that they are an integral part of their organization.

6.2. Limitations

The data for this study were initially planned for collection from the 5th to the 31st of March 2020. However, owing to unforeseen circumstances, the researcher started collecting data on the 5th of March 2020, but this process was hampered by the advent of COVID-19, which led the country to implement a lockdown in March. An extension was requested, and the data collection process continued in September 2020 and was completed during the same month. This caused a delay in the completion of this study within the anticipated timeframe. Another limitation of this study is its sample size. The initial sample size that was planned for this study was 300. Although 300 questionnaires were distributed, only 217 were returned. Of these 217, three (3) were spoiled questionnaires that could not be used. The researcher used 214 questionnaires that were considered sufficient to yield the required data.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the nature of organizational commitment, focusing on employees’ perceptions of the North West Provincial Department (Office of the Premier) regarding their level of organizational commitment. Most importantly, this study provided pertinent information on organizational commitment according to age, gender, and tenure (number of years in the organization). This study is significant because it provides empirical evidence that age has a bearing on organizational commitment. The empirical evidence reveals the significance of gender based on employees talking openly about the organization.

By examining organizational commitment using empirical research of this nature, this study established that employees’ commitment level was linked to a lack of alternative sources of employment and that attempting to leave their present department would require many personal sacrifices. This was especially true for older respondents aged between 55 and 64 years because the older one becomes, the fewer job opportunities become available. Naturally, most employers would prefer to invest in younger employees, as they are more likely to stay with the company longer than older employees, who are nearing retirement.

The aspect of belongingness also loomed large in this study’s findings, with some employees saying that they “did not feel like part of the family”. This finding resonates with those of previous studies that link organizational commitment and age (

Wang et al., 2020, p. 609). This study also established that younger employees (aged 25–34) were less likely to associate with the company’s problems. As such, the organization did not appear to have significant personal meaning for them. This lack of meaningful attachment to the company would most certainly affect the commitment level of such groups. Therefore, companies must consider increasing their commitment to younger employees.

Ultimately, it can be inferred that a committed employee is likely to have a positive attitude toward the organization and is more likely to be more productive because of a sense of belonging or connection with the organization and its goals.

This study critically examined the demographic factors influencing organizational commitment within the Office of the Premier, North West Province. Results indicate significant demographic correlations: younger employees demonstrated substantial affective commitment, older employees reflected higher continuance commitment, and gender differences significantly influenced openness in discussing organizational issues. These insights reinforce demographic considerations’ crucial role in organizational management, offering strategic guidance for enhancing employee commitment and retention.

Future studies could examine nuanced ways to nurture and sustain organizational commitment among all employees. Additionally, future research could use a larger sample size, which would make these findings more generalizable. Furthermore, future research should expand sample sizes and explore interventions tailored explicitly for younger employees to foster deeper organizational connections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; methodology, K.D.M.; software, K.D.M.; validation, K.D.M. and M.A.M. formal analysis, K.D.M.; investigation, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; resources, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; data curation, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; writing—review and editing, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; visualization, K.D.M. and M.A.M.; supervision, M.A.M.; project administration, K.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was granted its permission by the North-West University Research Ethics Regulatory Committee (NWU-RERC) based on the approval of the Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EMS-REC) on 29/01/2019, with ethics number: NWU-00183-19-A4.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on the Master Thesis “The effect of career orientation on organizational commitment and performance: A case of North West Province”, authored by Keolopile D. Motsaathebe, and completed at the North-West University, Mahikeng, South Africa, in May 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdullah, N. N. (2019). Probing the level of satisfaction towards the motivation factors of tourism in Kurdistan Region. Scholars Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 5(6), 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N. N., & Othman, M. B. (2021). Investigating the limitations of integrated tasks on youth entrepreneurship in Kurdistan region. Entrepreneur’s Guide, 14(2), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. (2023). Performance management. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Albalawi, A. S., Naugton, S., Elayan, M. B., & Sleimi, M. T. (2019). Perceived organizational support, alternative job opportunity, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A moderated-mediated model. Organizacija, 52(4), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabari, B., & Ghazzawi, I. (2019). Organizational commitment: A review of the conceptual and empirical literature and a research agenda. International Leadership Journal, 11(1), 78. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andavar, V., & Ali, B. J. (2020). Rainwater for water scarcity management: An experience of woldia university (Ethiopia). The Journal of Business Economics and Environmental Studies, 10(4), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, G., & Abdullah, N. N. (2021). The impact of Human resource management practice on organizational performance. International journal of Engineering, Business and Management (IJEBM), 5(1), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbari, M., Nurhayati, W., & Purwanto, A. (2019). The effect of parenting style and genetic personality on children character development. Jurnal Penelitian Dan Evaluasi Pendidikan, 23(2), 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhane, S. (2021). The effect of recruitment and selection on organizational performance: The case of Saint Mary’s University [Doctoral dissertation, St. Mary’s University]. [Google Scholar]

- Bouziri, H., Smith, D. R., Descatha, A., Dab, W., & Jean, K. (2020). Working from home in the time of COVID-19: How to best preserve occupational health? Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 77(7), 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. R., & Harvey, D. F. (2011). An experiential approach to organization development. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Chanana, N. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on employees organizational commitment and job satisfaction in reference to gender differences. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(4), e2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S. (2020). Will the pandemic bring industrial revolution 4.0 closer to home? In Human & technological resource management (HTRM): New insights into revolution 4.0 (pp. 157–166). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y. D., Zhuang, W. L., & Huan, T. C. (2019). Engage or quit? The moderating role of abusive supervision between resilience, intention to leave and work engagement. Tourism Management, 70, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T. T. T., Nguyen, L. C. T., & Nguyen, T. D. N. (2020). Emotional intelligence and project success: The roles of transformational leadership and organizational commitment. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(3), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhdr, H. R., & Aimer, N. M. (2020). The effect of personal factors on organizational commitment among teachers working at Libyan Schools in Turkey. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay-Mariani, L., & Adam, A. F. (2020). Uncovering the role of commitment in the entrepreneurial process: A research agenda. In The entrepreneurial behaviour: Unveiling the cognitive and emotional aspect of entrepreneurship (pp. 147–169). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Gasengayire, J. C., & Ngatuni, P. (2019). Demographic characteristics as antecedents of organizational commitment. Pan-African Journal of Business Management, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, D., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Chrupała-Pniak, M., Mello, A. L., & Paruzel-Czachura, M. (2019). Work ethic and organizational commitment as conditions of unethical pro-organizational behavior: Do engaged workers break the ethical rules? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 27(2), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego-Planer, D. (2019). The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors in the public and private sectors. Sustainability, 11(22), 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego-Planer, D. (2020). Three dimensions of organizational commitment of sports school employees. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar, R. (2020). Impact of affective commitment on employee performance special reference to the fenda communication and IT-KSA. International Journal of Management (IJM), 11(6), 1440–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, S., Ali, R. F., Ahmed, M., Humayon, A. A., Sajjad, M., & Ahmad, J. (2019). Barriers to implementation of emergency obstetric and neonatal care in rural Pakistan. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0224161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiningsih, P., Udin, U. D. I. N., Masdjojo, G. N., & Srimindarti, C. (2020). Does competency, commitment, and internal control influence accountability? The journal of Asian finance, Economics and Business, 7(4), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imelda, D., Asbari, M., Purwanto, A., Sestri Goestjahjanti, F., & Mustikasiwi, A. (2020). The effect of fairness of performance appraisal, job satisfaction and commitment on employees’ performance: Evidence from Indonesian automotive industry. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29, 2383–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, M. T., Anwar, I., Khan, N. A., & Saleem, I. (2021). Work during COVID-19: Assessing the influence of job demands and resources on practical and psychological outcomes for employees. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 13(3), 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karem, M. A., Mahmood, Y. N., Jameel, A. S., & Ahmad, A. R. (2019). The effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurses’ performance. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 7(6), 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, E. W., & Pienata, C. (2020). The role of organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behavior in hotel industry [Doctoral dissertation, Petra Christian University]. [Google Scholar]

- Keyvanlo, Z., Ghorbani, A., Tireh, H., & Tazegole, R. (2020). A survey of relationship between job satisfaction with organizational commitment and its influencing Factorsin employees of Sabzevar university of medical sciences. JSUMS, 26(5), 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. J., & Iqbal, J. (2020). Training and employee commitment: The social exchange perspective. Journal of Management Sciences, 7(1), 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q. I., Mumtaz, R., & Rehan, M. F. (2021). How do organizational commitment and work engagement mediate between human resource management practices and job performance? Review of Economics and Development Studies, 7(3), 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, M., & Nel, P. (2020). The influence of job resources on platinum mineworkers’ work engagement and organizational commitment: An explorative study. The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(1), 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklenski, J. (2021). Inclusive organizational development. In Diversity and organizational development: Impacts and opportunities (pp. 87–101). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S. A., Herbert, I. P., & Rothwell, A. T. (2020). Rethinking the Career Anchors Inventory framework with insights from a finance transformation field study. The British Accounting Review, 52(2), 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, R. B., Sanyal, S. N., & Mazumder, R. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment in school education sector. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(3), 716–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R. (2020). Impact of brand commitment and brand awareness on brand loyalty with customer satisfaction as a mediator. Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(8), 3272–3281. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, L., & Donohue, R. (2019). Antecedents of affective and normative commitment of organisational volunteers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(18), 2581–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, J. A., Cooper, B., & Wheeler, S. (2019). Mainstreaming gender into irrigation: Experiences from Pakistan. Water, 11(11), 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. K., & Bawole, J. N. (2020). Person–job fit matters in parastatal institutions: Testing the mediating effect of person–job fit in the relationship between talent management and employee outcomes. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(3), 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Morin, A. J., Rousseau, V., Boudrias, J. S., & Brunelle, E. (2021). Profiles of global and target-specific work commitments: Why compatibility is better and how to achieve it. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 128, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. (2020). Productivity of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from an employee survey. Covid Economics, 49(1), 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Muoghalu, O. J., & Tantua, E. (2021). Workplace ethics and employee commitment of oil and gas companies in Rivers State. International Journal of Business & Law Research, 9(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M. T., & Khoa, B. T. (2020). Improving the competitiveness of exporting enterprises: A case of Kien Giang province in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(6), 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, D., Asbari, M., Wijaya, M. R., & Yuwono, T. (2020). Effect of organizational justice on organizational commitment: Mediating role of intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction. International Journal of Science and Management Studies (IJSMS), 3(3), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H. S. (2019). Organizational commitment profiles and turnover intention: Using a person-centered approach in the Korean context. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otuohere, J. N. (2021). Employee commitment and organizational performance in hospitality industries in South-East Nigeria. International Journal of Business & Law Research, 9(2), 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Paramita, E., Lumbanraja, P., & Absah, Y. (2020). The influence of organizational culture and organizational commitment on employee performance and job satisfaction as a moderating variable at PT. Bank Mandiri (Persero), Tbk. International Journal of Research and Review, 7(3), 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, P., & Pandey, M. A. (2019). Creativity and innovation in reward & compensation practices. School of Management Sciences, 1(2), 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Penni, C. W. (2019). Job satisfaction and work-related motivation of aviation security agents: Empirical evidence from Ghana. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M. F., Kara, A., Fanimokun, A., & Smith, P. B. (2019). Country culture moderators of the relationship between gender and organizational commitment. Baltic Journal of Management, 14(3), 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M., Asif, M., Hussain, A., & Jameel, A. (2020). Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Review of Managerial Science, 14(6), 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshkumar, M. (2020). Employee engagement as an antecedent of organizational commitment—A study on Indian seafaring officers. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 36(3), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A., Delfabbro, P., & Calic, D. (2021). Encouraging employee engagement with cybersecurity: How to tackle cyber fatigue. SAGE Open, 11(1), 21582440211000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Lombard, M. (2020). Antecedents and outcome of commitment in Islamic banking relationships–an emerging African market perspective. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(6), 1851–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R., Eliyana, A., & Suryani, T. (2020). Green campus competitiveness: Implementation of servant leadership [Doctoral dissertation, Petra Christian University]. [Google Scholar]

- Soenanta, A., Akbar, M., & Sariwulan, R. T. (2020). The effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment to employee retention in a lighting company. Issues in Business Management and Economics, 8, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, M., Birnbaum, D., & Casal, J. (2019). Application of the person-centered model to stress and well-being research: An investigation of profiles of employee well-being. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 41(4), 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanavathi, C. (2021). Teachers’ perception on digital media technology. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(10), 6972–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindowen, D. J. (2019). Influence of empowerment on teachers’ organizational behaviors. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(2), 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A. F. (2020). Workplace incivility: A literature review. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(5), 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Albert, L., & Sun, Q. (2020). Employee isolation and telecommuter organizational commitment. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, H., Jufri, M., & Saman, A. (2020). The effect of authentic leadership and psychological capital on work engagement: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(8), 1139–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., Hao, Q., & Song, H. (2020). Linking supervisor support to innovation implementation behavior via commitment: The moderating role of coworker support. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(3), 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T., Qiu, Q., & Wei, Y. (2019). Retaining hotel employees as internal customers: Effect of organizational commitment on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty of employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Akhtar, M. N., Zhang, Y., & Rofcanin, Y. (2019). High-commitment work systems and employee voice: A multilevel and serial mediation approach inside the black box. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 41(4), 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Ng, T. W., & Lam, S. (2019). Promotion-and prevention-focused coping: A meta-analytic examination of regulatory strategies in the work stress process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(10), 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).