Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Reflection from Schumpeter’s Economic Sociology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Economic Sociology as a Lens for Studying Entrepreneurship

2.1. Economic Sociology Contribution to the Comprehension of the Economic Process

2.2. Entrepreneurship as a Field of Study in Economic Sociology

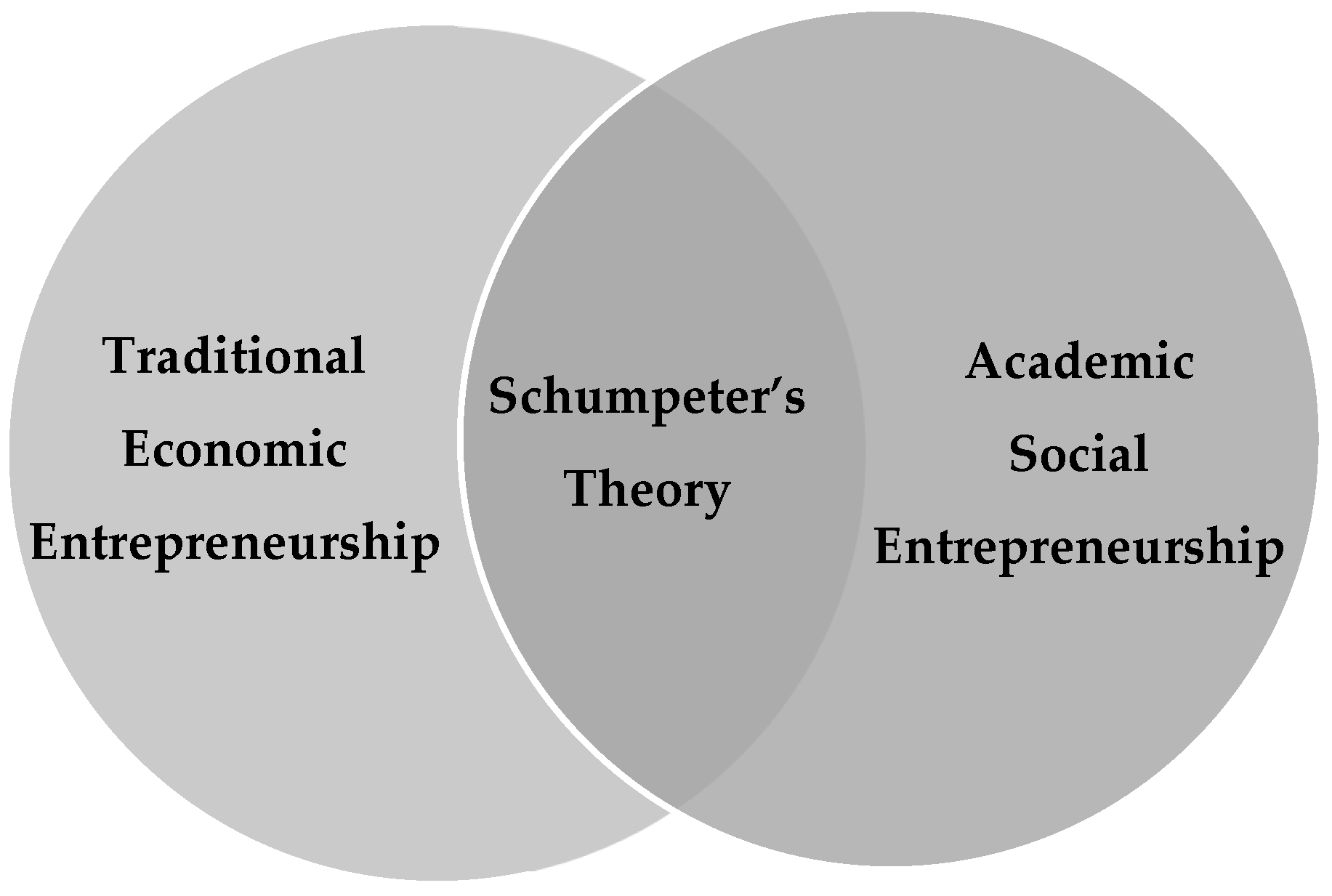

3. Current Overlaps for a New Type of Entrepreneur

3.1. Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation

3.2. Academic Entrepreneurship

4. Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Perspective Inspired by Schumpeterian Notes

- Motivations—Academic social entrepreneurs have complex motivations centered on a sense of mission and social value to create social change. In academic work, the entrepreneurial function is performed by the individual researcher or the research team and by other social actors with a stake in the social challenge.

- Social Innovations and New Knowledge Combinations—academic social entrepreneurs combine their scientific knowledge and technical skills to address pressing challenges for society introducing combination of new products, methods, markets, sources of raw materials, forms of organization, finance and legal forms. On debates on the concept of social innovation this is often expressed as both a product and a process that transforms social and power relations.

- Resistance and Context—Academic social entrepreneurs also face resistance to their endeavors, stemming from habits, traditions, routines, institutions, and social orders, both within academic institutions and the external organizations they are trying to affect. This resistance, often tied to institutional inertia, can be a major barrier to implementing innovations.

- Social Value—Social change at local, national, and international levels often involves creating new organizations, institutions, and/or laws that help achieve innovation and economic and social value. Whereas economic value is often expressed in profit, social value is related, ultimately, to social change.

- Systemic transformation—The parallel to the concept of creative destruction within a social innovation framework is the idea of systemic transformation, in the sense that social innovations have an effect in changing social structures and therefore contribute to societal evolution.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anders, L.; Stevenson, L. Entrepreneurship Policy—Theory and Practices; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nadim, A.; Hoffmann, A.N. A Framework for Addressing and Measuring Entrepreneurship; OECD Statistics—Entrepreneurship Indicators Steering Group: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. History of Economic Analysis; Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1939; Volumes 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R. Joseph A. Schumpeter: His Life and Work; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Horizon Europe: The EU Research and Innovation Programme (2021–2027). Horizon Europe the EU’s Funding Programme for Research and Innovation. 2020. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/horizon-europe_en (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- National Science Foundation. SBIR: Small Business Innovation Research Program. NSF 19-554: Small Business Innovation Research Program Phase I. 2019. Available online: https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/small-business-innovation-research-program-phase-i/505233/nsf19-554/solicitation (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Graça, J. Afinal, o que é mesmo a Nova Sociologia Económica? Rev. Crít. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 73, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Major traditions of economic sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1991, 17, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.M.; Voldnes, G. An Integrated Economic Sociology Approach to Market-as-Network: The Example of a Shared Business Environment Between Norway and China. J. East-West Bus. 2021, 27, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.; Smelser, N.J. Economic sociology: Historical threads and analytic issues. Curr. Sociol. 1990, 38, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Schumpeter’s full model of entrepreneurship: Economic, non-economic and social entrepreneurship. In An Introduction to Social Entrepreneurship: Voices, Preconditions, Contexts; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, P. Economic Sociology; Taylor & Francis: Routledge Historical Resources: History of Economic Thought. 2017. Available online: https://www.routledgehistoricalresources.com/economic-thought/essays/economic-sociology (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Smelser, N.; Swedberg, R. Introducing economic sociology. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbin, F. Comparative and Historical Approaches to Economic Sociology. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism; Parsons, T., Translator; Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. De la Division du Travail Social [The Division of Labor in Society]; Alcan: Paris, France, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, T.; Swedberg, R. Capitalist entrepreneurship: Making profit through the unmaking of economic orders. Capital. Soc. 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Social entrepreneurship: The view of the young Schumpeter. In Entrepreneurship as Social Change; 2006; pp. 21–34. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/9781845423667.00010.xml (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Pinto, H.; Cruz Rita, A.; de Almeida, H. Academic entrepreneurship and knowledge transfer networks: Translation process and boundary organizations. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurial Success and Its Impact on Regional Development; Information Science Reference: Hershey PA, USA, 2015; pp. 315–343. [Google Scholar]

- Link, A.N.; Siegel, D.S. Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Technological Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, S.; Grigore, A.; Marinescu, P. Economic development and entrepreneurship. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 8, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W. Is there an elephant in entrepreneurship? Blind assumptions in theory development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2001, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, A. Entrepreneurship and economic development from classical political economy to economic sociology. J. Econ. Stud. 2005, 32, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, S.; Anderson, A.; Jack, S. “Let them not make me a stone”—Repositioning entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 1842–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.; Peters, M.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurship, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S. Empreendedorismo e Inovação; Escolar Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, O.; Roman, A.; Rusu, V.D. The nexus between entrepreneurship and economic growth: A comparative analysis on groups of countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruef, M.; Lounsbury, M. Introduction: The sociology of entrepreneurship. Res. Sociol. Organ. 2007, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, E.G. Vertentes teóricas sobre empreendedorismo. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2009, 40, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R. The social science view of entrepreneurship: Introduction and practical applications. In Entrepreneurship: The Social Science View; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 7–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thurik, A.R.; Audretsch, D.B.; Block, J.H.; Burke, A.; Carree, M.A.; Dejardin, M.; Rietveld, C.A.; Sanders, M.; Stephan, U.; Wiklund, J. The impact of entrepreneurship research on other academic fields. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P. Sociology and entrepreneurship: Concepts and contributions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F. The Role of the Entrepreneur in Social Change in Northern Norway; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mollick, E. The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Venturing 2014, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. onceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 32–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J. The Meanings of Social Entrepreneurship, Reformatted and Revised Version; Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship: Durham, NC, USA, 2001; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, R. Introduction: Voices, preconditions, contexts. In An Introduction to Social Entrepreneurship: Voices, Preconditions, Contexts; Ziegler, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Northampton, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B. Framing a Theory of Social Entrepreneurship: Building on Two Schools of Practice and Thought. In Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field; Mosher-Williams, R., Ed.; ARNOVA Occasional Paper Series; ARNOVA: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, J.; Cheney, G. The meanings of social entrepreneurship today. Corp. Gov. 2005, 5, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J.; Linder, S. Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E. Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: Towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. Int. Small Bus. J. 2007, 25, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E. Entrepreneurship. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology, 2nd ed.; Smelser, N.J., Swedberg, R., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. Social Innovation: Utopias of Innovation from c. 1830 to the Present; Working Paper; Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink? Enterp. Res. Cent. 2015, 32, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. Incubation of incubators: Innovation as a triple helix of university. Sci. Public Policy 2002, 29, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klofsten, M.; Jones-Evans, D. Comparing academic entrepreneurship in Europe—The case of Sweden and Ireland. Small Bus. Econ. 2000, 14, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.; Campbell, D. Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other? A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 1, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university-industry-government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantaragiu, R. Towards a conceptual delimitation of academic entrepreneurship. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2012, 7, 683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Klofsten, M. The innovating region: Toward a theory of knowledge-based regional development. R&D Manag. 2005, 35, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, M.F.; Xavier, J.A.; Amin, M. Social entrepreneurship and sustainability: A conceptual framework. J. Soc. Entrep. 2024, 15, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford University Innovation. Social Enterprise Development Programme. Oxford University Innovation Annual Report. 2021. Available online: https://innovation.ox.ac.uk/about/social-ventures/funding-social-enterprise/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Stanford Center for Social Innovation. Social Innovation Fellowship. Stanford Graduate School of Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/experience/about/centers-institutes/csi (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Leca, B.; Gond, J.P.; Barin Cruz, L. Building ‘Critical Performativity Engines’ for Deprived Communities: The Construction of Popular Cooperative Incubators in Brazil. Organization 2014, 21, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.B.; Eesley, C.E. Entrepreneurial Impact: The Role of MIT; Kauffman Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. Weber’s Last Theory of Capitalism: A Systematization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1980, 45, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Powell, W. Institutions and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 201–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carland, J.; Boulton, F.; Carland, J. Differentiating entrepreneurs from small business owners: A conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Entrepreneur. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences; Sills, D.L., Ed.; Collier Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1968; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gieure, C.; del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, M.; Roig-Dobón, S. The Entrepreneurial Process: The Link Between Intentions and Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R.; Schumpeter, J.A. The Economics and Sociology of Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D.A. ‘New combinations’ in Schumpeter’s economics: The lineage of a concept. Hist. Econ. Rev. 2020, 75, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Gómez, J.A.; Pinto, H.; González-Gómez, T. The social role of the university today: From institutional prestige to ethical positioning. In Universities and Entrepreneurship: Meeting the Educational and Social Challenges; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2021; pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, S.; Brito, C. Academic entrepreneurship intentions: A systematic literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 645–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, H.; Nogueira, C.; Guerreiro, J.A.; Sampaio, F. Social Innovation and the Role of the State: Learning from the Portuguese Experience on Multi-Level Interactions. World 2021, 2, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pel, B.; Haxeltine, A.; Avelino, F.; Dumitru, A.; Kemp, R.; Bauler, T.; Kunze, I.; Dorland, J.; Wittmayer, J.; Jørgensen, M.S. Towards a theory of transformative social innovation: A relational framework and 12 propositions. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw, S.; Mamas, M.A.; Topol, E.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mainstream Economics | Economic Sociology | |

|---|---|---|

| Protagonist | The individual agent | Interplay between actors, groups, institutions |

| Economic action | The actor has a certain set of preferences and will choose the one that maximizes utility (rational action) | Various possible types of economic action |

| Choice | Rational action as the efficient use of scarce resources | The view is broader and more comprehensive |

| Focus | Market exchange | The economic process is embedded in an organic way within society |

| Objectives of analysis | Formal approaches focused on predicting behavior | Descriptive and theoretical analyses |

| Methodological approaches | Formal models focused on mathematics and statistical methods | A greater variety of methods, such as observation, analysis of qualitative data, among others |

| Intellectual inspirations | Neoclassical economics, showing a clear distinction between the study of the economy, the current economic theory, and the history of economic thought | Sociological traditions and theories to explain the economy, pluralism, and overlap with other disciplinary areas such as social studies of science or political economy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, H.; Sampaio, F.; Ferreira, S.; Elston, J. Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Reflection from Schumpeter’s Economic Sociology. Businesses 2024, 4, 723-737. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040040

Pinto H, Sampaio F, Ferreira S, Elston J. Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Reflection from Schumpeter’s Economic Sociology. Businesses. 2024; 4(4):723-737. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040040

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Hugo, Fábio Sampaio, Sílvia Ferreira, and Jennifer Elston. 2024. "Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Reflection from Schumpeter’s Economic Sociology" Businesses 4, no. 4: 723-737. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040040

APA StylePinto, H., Sampaio, F., Ferreira, S., & Elston, J. (2024). Academic Social Entrepreneurship: A Contemporary Reflection from Schumpeter’s Economic Sociology. Businesses, 4(4), 723-737. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040040