Innovative Strategies and Transformations in the Montilla–Moriles Wine-Production Area: Adaptation and Success in the Global Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. History and Evolution of Viticulture in Montilla–Moriles in the 20th Century

2.2. Evolution of the Wine Sector in the 21st Century

2.3. Current Context of the Montilla–Moriles PDO

2.4. Regulation of the Sector in the European Union

2.5. Strategic Plan of the Montilla–Moriles PDO

- Small-scale dryland viticulture (average farm size of 3 hectares, with 70% of farms having an area of less than 5 hectares); direct exploitation predominated (99%) over leasing or sharecropping.

- Farmers (around 4000 at the time) generally worked only part-time in the vineyards. They were typically individuals with other sources of income (wages, rents, pensions, small businesses, etc.) who supplemented their income with self-employment on their modest farms.

- Yields per hectare were low (ranging from 4000 to 9000 kg of fruit per hectare, depending on climatic conditions).

- Grape prices in the area were very low compared to better-known wine-producing regions.

- Half of all processing was carried out in cooperatives (with 14 in operation), and the other half in about 85 traditional wine presses. Cooperatives played a particularly important role in the production of the traditional sweet wine Pedro Ximénez, which was produced by three of them.

- Aging and marketing, on the other hand, were concentrated in private wineries (90%), with only 10% of commercialization done by cooperatives. The Montilla–Moriles PDO had 22 wineries that were joint-stock companies and 16 limited liability companies. Generally, the shareholders in these companies were all close relatives, with some isolated cases in which some of the shareholders were unrelated individuals. Additionally, there were 42 other individual businesses owned by one or several persons but not constituting a company. In these businesses, the activity basically involved the processing of the harvest, with very limited aging or wood maturation capacity.

- Sales were mainly oriented towards the domestic market (75–80% of sales): Andalusia, Madrid, and Catalonia. Export (20–25%) was concentrated in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

- In terms of pricing and consumer awareness, Montilla wines lagged behind those from Jerez and Malaga but were well ahead of those from Huelva.

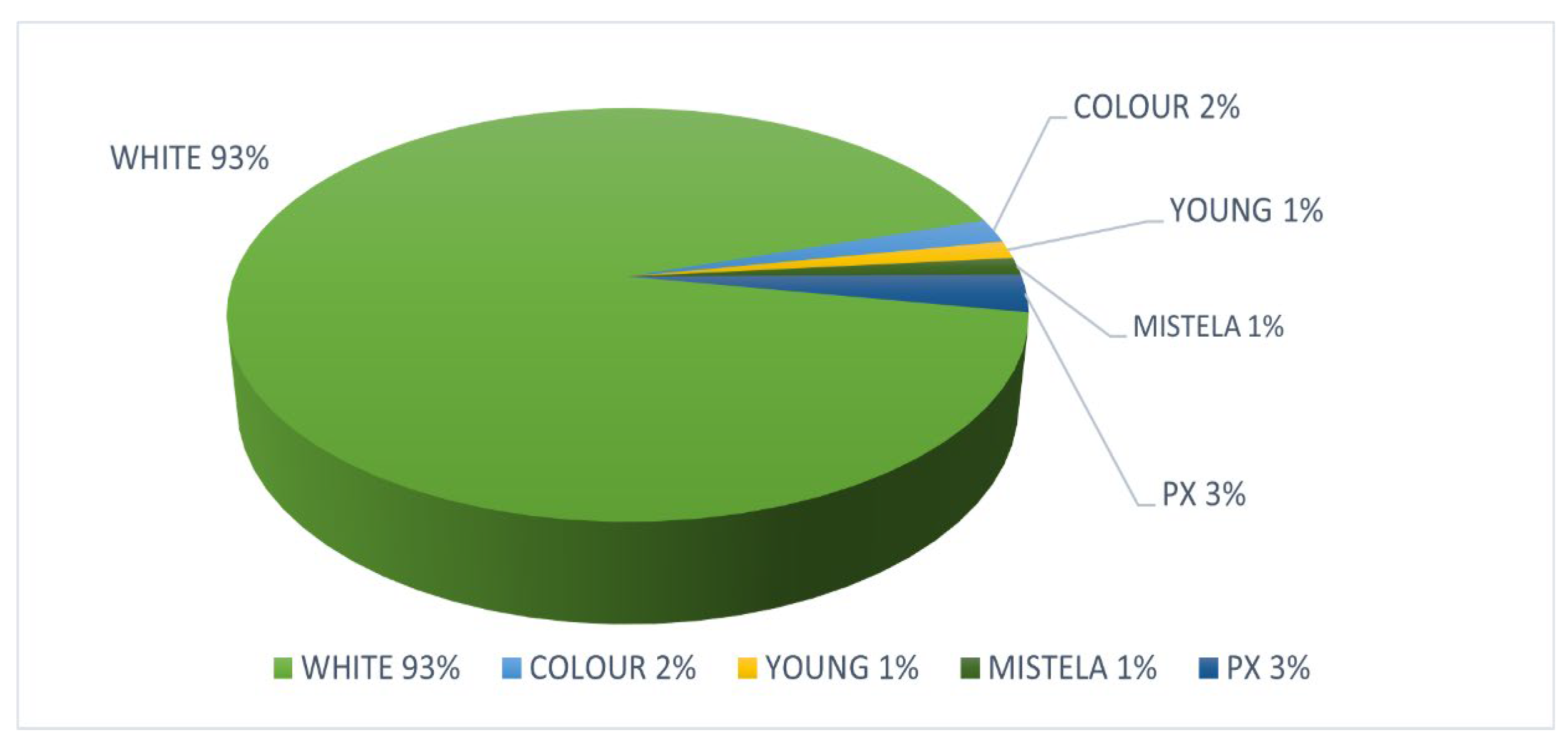

- The products produced are shown in Figure 4. The production of fine wines stands out, with sweet Pedro Ximénez wines accounting for only 4% of the volume produced (in the 1999 Strategic Plan, some actions for product diversification were proposed, which have subsequently materialized).

2.6. SWOT Analysis and Current Situation of the Montilla–Moriles PDO

3. Materials and Methods

4. Case Study Results

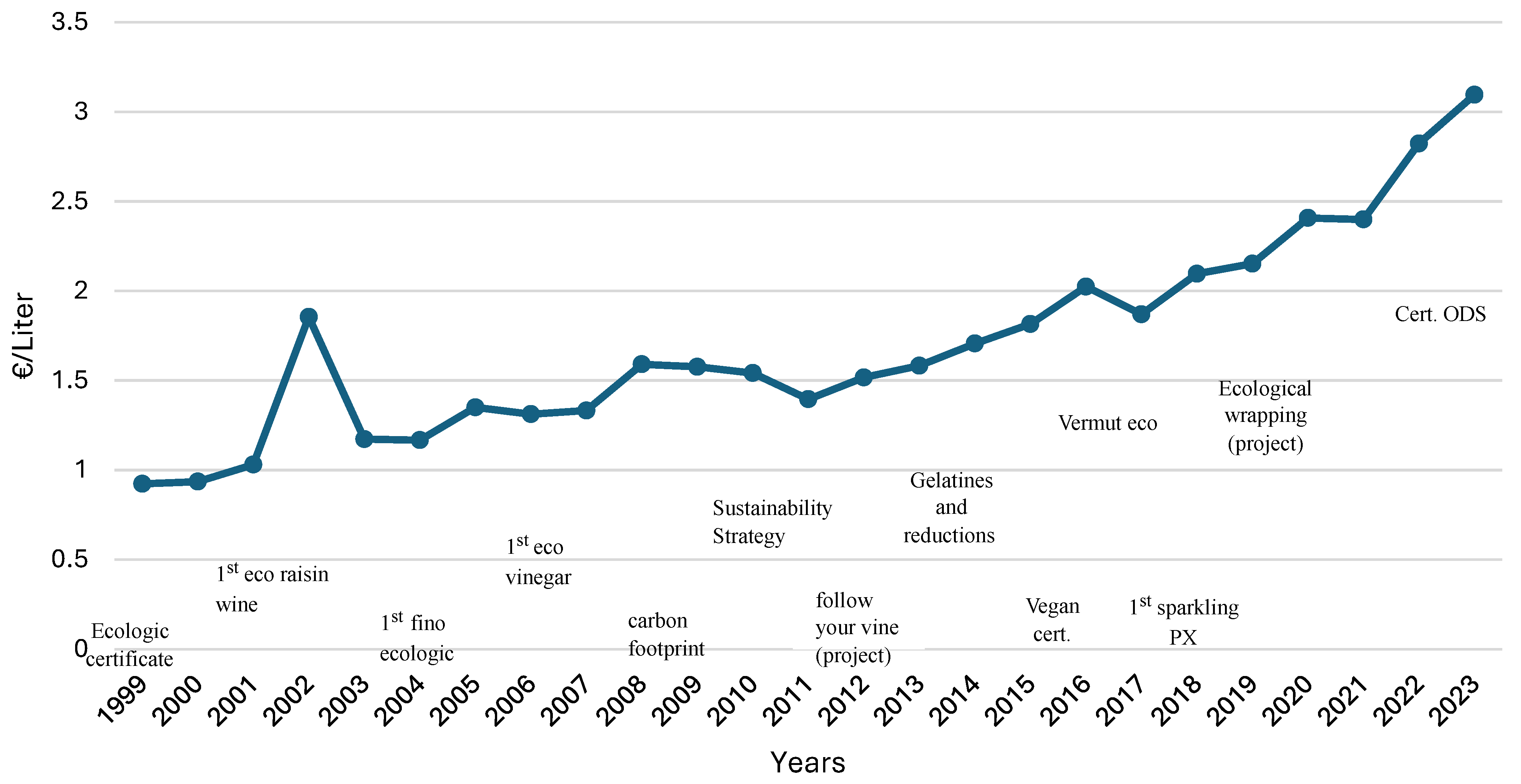

4.1. Bodegas Robles

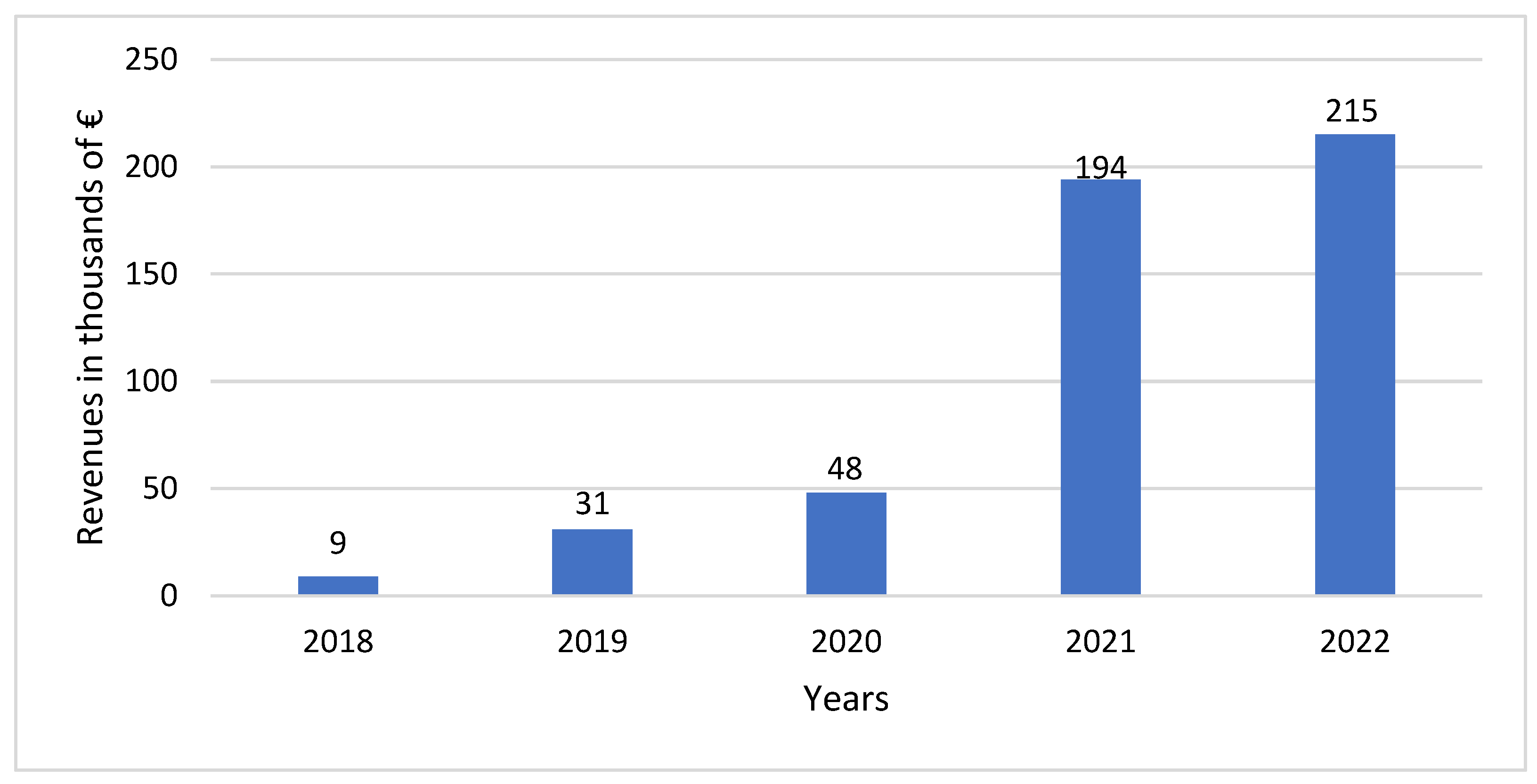

4.2. Lagar la Salud Winery

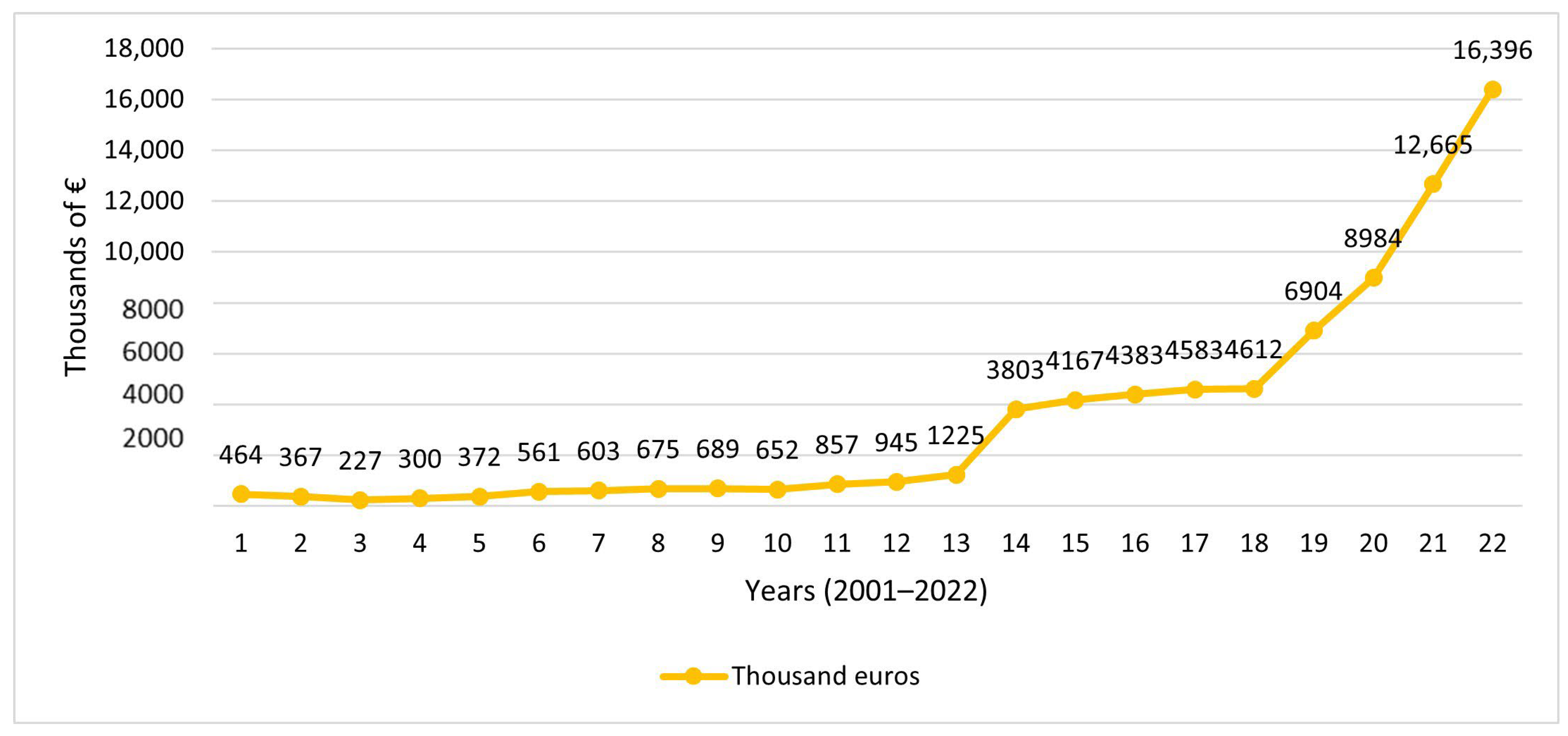

4.3. Tonelería del Sur–Casknolia

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Mastery of traditional techniques and leveraging local knowledge.

- Innovation in products, with constant new releases that balance and enrich the product portfolio.

- Offering differentiated products from the region based on quality and distinct attributes, focusing on value rather than costs.

- Concern for sustainability and striving to project an image of responsibility.

- Targeting segments that are underserved or underexploited by local wineries (knowledgeable and young customers).

- Orienting towards international markets and emerging trends far removed from the domestic market.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonanno, A. La globalización agro-alimentaria: Sus características y perspectivas futuras. Sociologías 2003, 5, 190–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, T.L. The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T. La Tierra es Plana: Breve Historia del Mundo Globalizado del Siglo XXI.; Ediciones Martínez Roca: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón-García, R.G. Florido-Trujillo, and R.F. Vega-Pozuelo, Un espacio agrario entre el retroceso y la reestructuración: El viñedo de Montilla-Moriles (Córdoba, España). Estud. Geográficos 2022, 83, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-García, F.J. Montilla-Moriles, una vitivinicultura pendiente de estudio. In Actas del I Encuentro de Historiadores de la Vitivinicultura Española; Ayuntamiento de El Puerto de Santa María: Cádiz, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Loma Rubio, M. La llegada de la filoxera al viñedo cordobes. Axerquía: Rev. De Estud. Cordobeses 1982, 5, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, J.L. Wine and Conventions: A Fruitful Coupage. In Handbook of Economics and Sociology of Conventions; Diaz-Bone, R., Larquier, G.d., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Consejería de Agricultura. Diagnóstico del Sector Vitivinícola en el Marco Montilla-Moriles; Junta de Andalucia: Sevilla, Spain, 2003; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.S.M.; Canizares, S.; García, R. Wine routes in Spain: A case study. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2009, 57, 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Triviño Tarradas, P.M. Evaluación y Mejoras para el Manejo Sostenible de la Explotación Vitivinícola en la DOP; Montilla-Moriles: Córdoba, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-García, F.J.; Veroz-Herradón, R. Plan Estratégico de la D.O. Montilla Moriles; Diputación de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2000; p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Ontiveros, A. Evolución de los Cultivos en la Campiña de Córdoba del siglo XIII al siglo XIX.; Papeles de Geografía: Murcia, Spain, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, D.R. Los comerciantes españoles del vino de Jerez durante la época de Carlos III. In El Jerez-Xérès-Sherry en los Tres Últimos Siglos: Curso de la UIMP Celebrado en 1994; Ayuntamiento de El Puerto de Santa María: Cádiz, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado Rosso, J. Cambios de Consumo y de Gusto de los Vinos de Jerez en el Reino Unido y sus Consecuencias en la Zona de Producción Entre Mediados de los Siglos XVIII y XIX; Universidad de: Cádiz, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés, E. El vino de Jerez en el sector exterior español, 1838-1885. Rev. De Hist. Ind. 2000, 17, 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pemartín, J. Diccionario del Vino de Jerez; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo, M. Pequena y gran propiedad en la depresion del Guadalquivir. In Aportacion al Estudio de la Genesis y Desarrollo de Una Estructura de Propiedad Agraria Desigual. Secretaría General Técnica; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Albaladejo, F. Intervención estatal del sector vitivinícola español durante el franquismo: Las bodegas cooperativas. In Agro y Política a Uno y Otro Lado del Atlántico: Franquismo, Salazarismo, Varguismo y Peronismo; Universidad Nacional de San Martín: San Martín, Perú, 2016; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Pino, J. Montilla, 1950–1975, Entre la Historia y la Memoria; Autoedición: Montilla, Spain, 1994; p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. Perspectivas de la Producción Mundial del Vino; OIV: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, G.; Martinelli Lasheras, P. Risk management in traditional agriculture: Intercropping in Italian wine production. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 2024, 28, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Netzer, Y. Long-term trends of global wine market. Agriculture 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, J.L. Blancos, tintos frutales y desalcoholizados marcan tendencia en el vino. Distrib. Y Consumo 2023, 4, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pomarici, E.; Corsi, A.; Mazzarino, S.; Sardone, R. The Italian Wine Sector: Evolution, Structure, Competitiveness and Future Challenges of an Enduring Leader. Ital. Econ. J. 2021, 7, 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercasa Vino y Mosto. Anuario de Alimentación en España; Ministerio de Agricultura: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 421–454. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Rosentrater, K.A. Estimating Economic and Environmental Impacts of Red-Wine-Making Processes in the USA. Fermentation 2019, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Wine Production Reached 16.1 billion Litres in 2022; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía, Orden de 25 de noviembre de 2020, por la que se Aprueba la Modificación Normal del Pliego de Condiciones de la Denominación de Origen Protegida «Montilla-Moriles». G. Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Desarrollo Sostenible, Editor. 2020, Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía—BOJA: Boletín Número 234 de 03/12/2020. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2020/234/14.html (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Fuentes-García, F.J.; Veroz-Herradón, R.; Martín Lozano, J.M. La nueva OCM del vino, oportunidades y amenazas para la vitivinicultura española. In Proceedings of the Anales de Economía Aplicada, XIV Reunión ASEPELT, Oviedo, Spain, 22–23 June 2000; pp. 1–9, ISBN 84-699-2357-9. [Google Scholar]

- Soler Montiel, M.M. Impactos económicos, sociales y territoriales de la globalización de los mercados del vino. In V Reunión de Economía Mundial; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, P. Reforma OCM: Crónica de un proyecto destrozado. Acenología Rev. De Enol. Científica 2008, 90, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Boel, M. Nuevas perspectivas en la viticultura derivadas de la reforma del vino. Acenología Revista Enología Científica 2008, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquiro Capera, J.D. La resiliencia organizacional, factor clave para lograr la supervivencia empresarial y la creación de valor. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2023, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafagy, A.; Vigani, M. Technical change and the Common Agricultural Policy. Food Policy 2022, 109, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Sardone, R. EU wine policy in the framework of the CAP: Post-2020 challenges. Agric. Food Econ. 2020, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Baron, H. The CAP (Common Agricultural Policy): A Short History of Crises and Major Transformations of European Agriculture. In Forum for Social Economics; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tribunal de Cuentas Europeo. Informe especial Reestructuración y plantación de viñedos en la UE. In Efectos Pocos Claros Sobre Competitividad y Ambición Ambiental Limitada; European Court of Auditors: Luxembourg, 2023; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, P.y.A. Orden de 12 de Diciembre de 1985 por la que se Ratifica el Reglamento de la Denominación de Origen «Montilla-Moriles» y de su Consejo Regulador; BOE-A-1985-26826: BOE.; BOE: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 40598–40605. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía, Orden de 30 de Noviembre de 2011, por la que se Aprueba el Reglamento de Funcionamiento de las Denominaciones de Origen «Montilla-Moriles» y «Vinagre de Montilla-Moriles», así Como sus Correspondientes Pliegos de Condiciones. C.d.A.y. Pesca, Editor. 2011, BOJA: Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía—BOJA. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2011/249/37 (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Ministerio de Agricultura. Diagnostico y análisis estrategico del sector agroalimentario español. In Análisis de la cadena de valor de la producción y distribución del vino; UNCUYO: Madrid, Spain, 2004; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Chingay, S.N.S.; Mendoza Alfaro, W.I.; Miranda Guerr, M.d.P.; Esparza Huamanchumo, R.M. Resiliencia y competitividad empresarial: Una revisión sistemática, período 2011–2021. Revista Ciencias Sociales (Ve) 2022, 28, 1–11, ISSN: 1315-9518. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.; Guinot, J.; Chiva, R.; López-Cabrales, Á. How to emerge stronger: Antecedents and consequences of organizational resilience. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- SABI—Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibericos. (Base de datos). 2024. Available online: https://sabi.informa.es/version-20230626-10-3/home.serv?product=SabiInforma& (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Yaniv, E. Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma Chaves, P. Capacidades Dinámicas y Éxito Internacional. Empresas Españolas en Tiempos de Crisis Económica; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G. The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Rho, S. An evolutionary perspective on strategic group emergence: A genetic algorithm-based model. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 727–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; El Sawy, O.A. Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decis. Sci. 2011, 42, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, B.; Informa, S. Sabi: Sistemas de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos. Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing SA: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Garcia, F.J.; Javier Carea-Ramirez, L.; Sanchez-Canizares, S.M. Longevity in the family business: The Alvear case (1729–1906). Rev. De Hist. Ind. 2019, 28, 13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, J.R.; García-Cortijo, M.C.; Pinilla, V.; Castillo-Valero, J.S. The business model and sustainability in the Spanish wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Winery | Year | Location |

|---|---|---|

| San Acacio Cooperative | 1962 | Montemayor |

| Jesus Nazareno Cooperative | 1963 | Baena |

| La Local Cooperative | 1963 | Aguilar de la Frontera |

| La Aurora Cooperative | 1964 | Montilla |

| La Purisima Cooperative | 1970 | Puente Genil |

| La Union Cooperative | 1979 | Montilla |

| Wine Type | Description | Tasting Notes | Alcohol Content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From the Montilla–Moriles PDO | Fino | Dry and light wine, aged under a layer of flor yeast | Pale color, sharp aroma, delicate taste with almond notes | 15–17% |

| Amontillado | Starts as fino, but with additional oxidative aging | Amber color, hazelnut aroma, dry taste with woody notes | 16–22% | |

| Oloroso | Dry and robust wine, completely oxidative aging | Mahogany color, intense nutty aroma, powerful and complex flavor | 17–22% | |

| Palo Cortado | Combines characteristics of Amontillado and Oloroso | Dark amber color, dry fruit aroma, dry and elegant flavor | 17–22% | |

| Pedro Ximénez (PX) | Natural sweet wine made from sun-dried grapes | Dark color, raisin, and honey aroma, very sweet taste with caramel and fig notes | 15–18% | |

| Moscatel | Sweet wine made from Muscat grapes | Golden color, floral and citrus aroma, sweet and fruity taste | 15–18% | |

| From outside the Montilla–Moriles PDO | Young white wines | Fresh and fruity wines made from Pedro Ximénez and other white grape varieties | Pale yellow color, fruity and floral aromas, light and refreshing taste | 10–12% |

| Red wines | Made from varieties such as Tempranillo and Syrah | Intense red color, red fruit, and spice aromas, robust and structured taste | 12–14% | |

| Type of Aging Process | Biological aging | Aging under a layer of flor yeast, avoiding contact with air | Examples: Fino and the initial stage of Amontillado | |

| Oxidative aging | Aging in contact with air, which produces oxidation | Examples: Oloroso, Palo Cortado, and the final stage of Amontillado | ||

| Mixed aging | Combination of biological and oxidative aging | Examples: Amontillado and Palo Cortado |

| 1985 Regulation | 1995 Amendment | 2011 Regulation | 2020 Specification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grape Varieties | Pedro Ximénez, Layrén, Baladí, Moscatel, and Torrontés | Unchanged | Subject to vineyard registration | Added foreign varieties like Verdejo, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Macabeo |

| Products | Fortified wines with aging (fino, amontillado, oloroso, palo cortado, raya) Unfortified fortified wines (ruedos) Pedro Ximénez (natural sweet and moscatel) Young white wines | Unchanged | Added types like pale cream and cream Added vinegar | Unchanged |

| Fine wine Alcohol Content (% vol.) | 14–17.5 | 15–17.5 | 15–17.5 | 14.5–17 |

| Strategic Lines from the 1999 Plan | Main Actions Performed |

|---|---|

| Inclusion of new varieties in the area, uprooting of less productive vineyards Mechanized trellis plantations Advances in organic plantations Modest development of wine tourism |

| Incorporation of new generations of winemakers and professionals in some companies. Closure of numerous wineries and cellars Development of new products (vinegars, wines of lower alcoholic content, wines in jars, fresh or unfiltered wines, wines on the vine). Other non-PDO products (sparkling and table wines) |

| Some cooperation actions (wine-on-the-branch project) involving 11 companies. Organization of events (flamenco tastings, concerts, and visits to winery patios). Marketing of organic wines and young white wines. Some winery brands and terroir winemaking |

| Weaknesses | Threats |

|---|---|

|

|

| Strengths | Opportunities |

|

|

| Companies | In 1999 | In 2023 | %Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winegrowers | 4338 | 1617 | −63% |

| Wineries | 83 | 33 | −60% |

| Cooperatives with vine-growing activity (several of them also olive growers) | 14 | 8 | −36% |

| Wineries for aging | 68 | 52 | −24% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes-García, F.J.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; González-Mohíno, M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J. Innovative Strategies and Transformations in the Montilla–Moriles Wine-Production Area: Adaptation and Success in the Global Market. Businesses 2024, 4, 531-552. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040032

Fuentes-García FJ, Sánchez-Cañizares SM, González-Mohíno M, Cabeza-Ramírez LJ. Innovative Strategies and Transformations in the Montilla–Moriles Wine-Production Area: Adaptation and Success in the Global Market. Businesses. 2024; 4(4):531-552. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040032

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes-García, Fernando J., Sandra M. Sánchez-Cañizares, Miguel González-Mohíno, and L. Javier Cabeza-Ramírez. 2024. "Innovative Strategies and Transformations in the Montilla–Moriles Wine-Production Area: Adaptation and Success in the Global Market" Businesses 4, no. 4: 531-552. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040032

APA StyleFuentes-García, F. J., Sánchez-Cañizares, S. M., González-Mohíno, M., & Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J. (2024). Innovative Strategies and Transformations in the Montilla–Moriles Wine-Production Area: Adaptation and Success in the Global Market. Businesses, 4(4), 531-552. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040032