Unveiling the Shadow of Workplace Cyberbullying in the Digital Age: A Call for Research in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cyberbullying at Work

2.1. Antecedence of Cyberbullying in the Workplace

2.2. Outcomes and Consequences of Workplace Cyberbullying

3. Materials and Methodology

4. Results

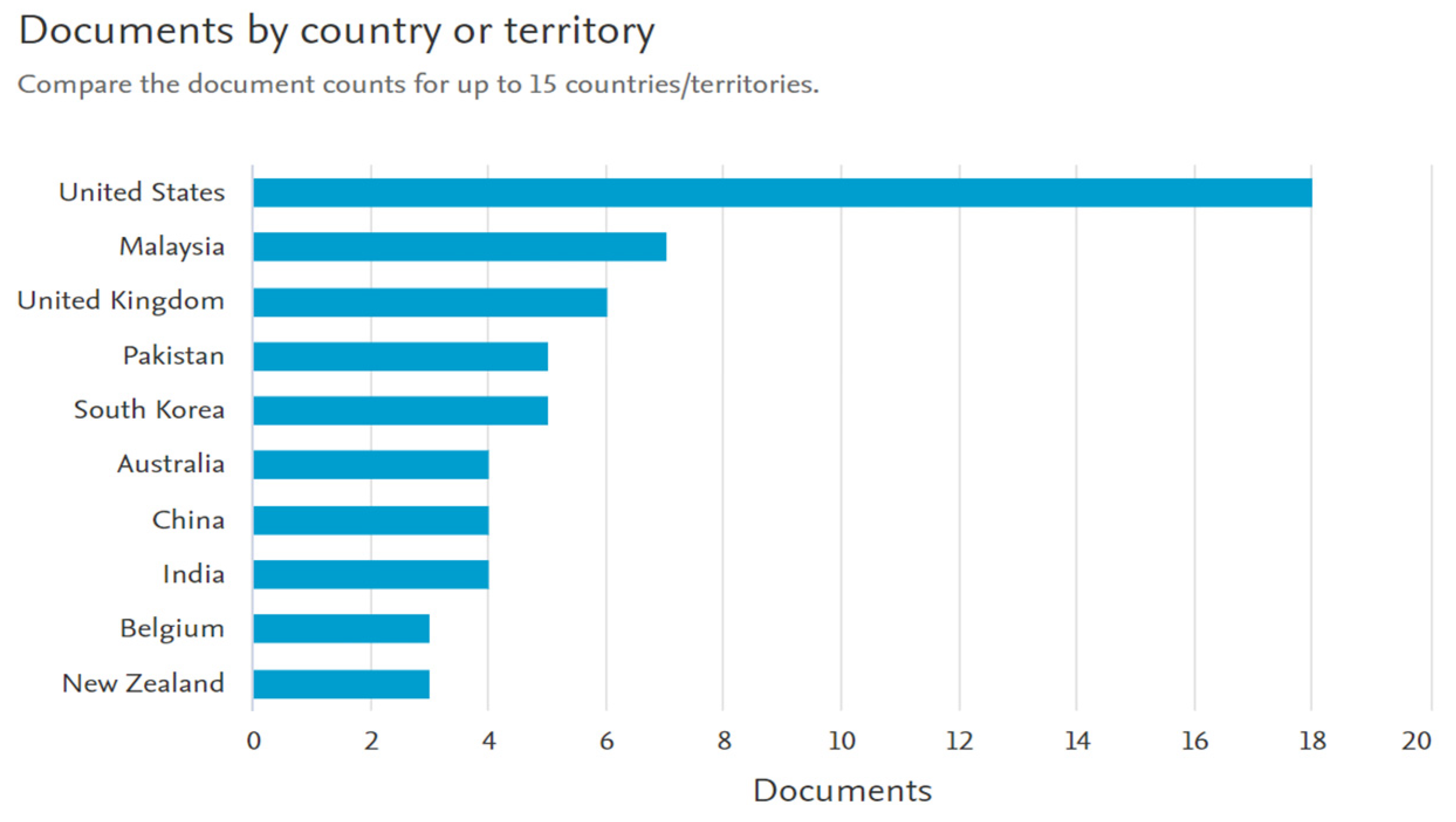

4.1. Publication per Country

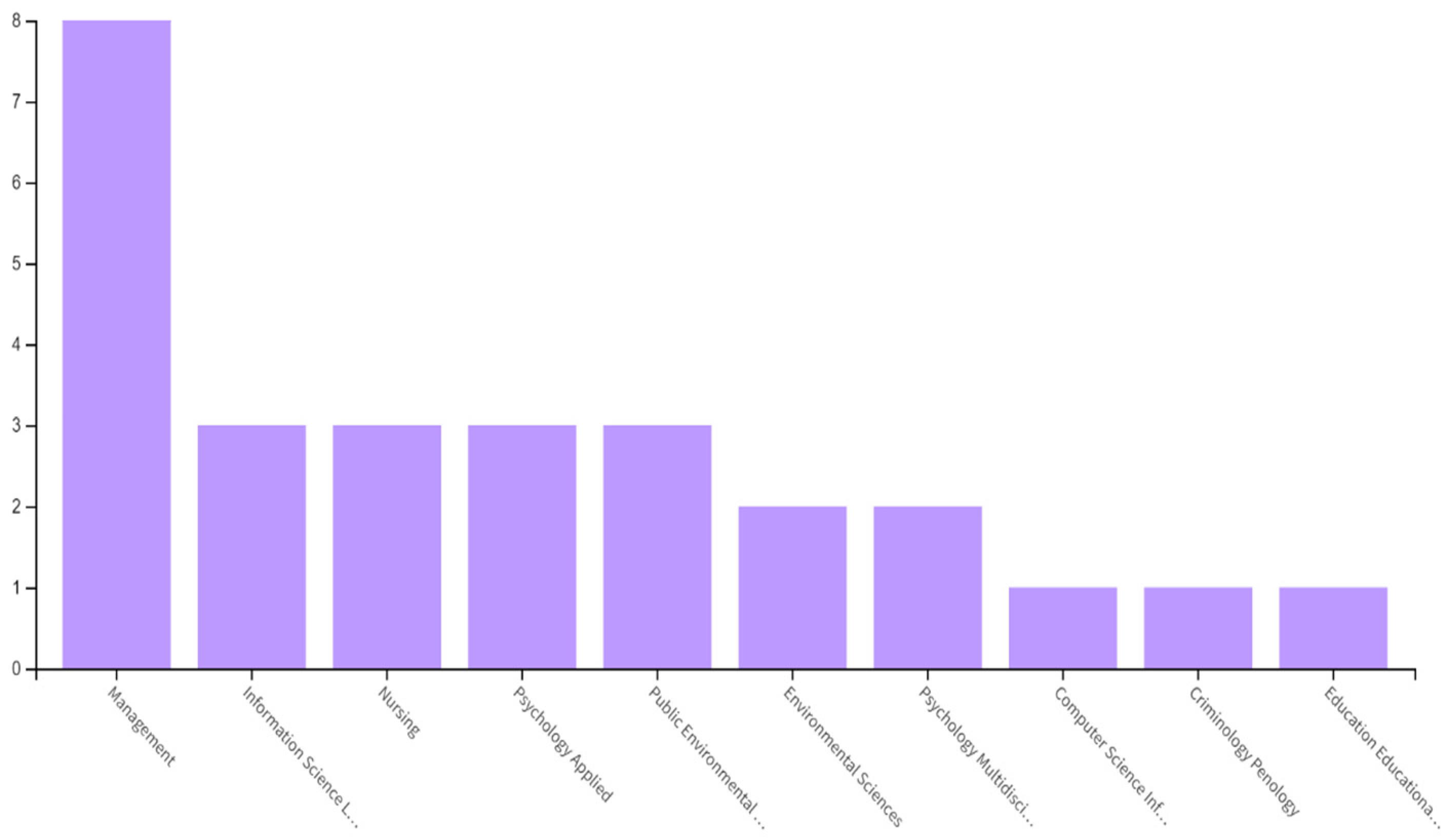

4.2. Publication per Subject Area

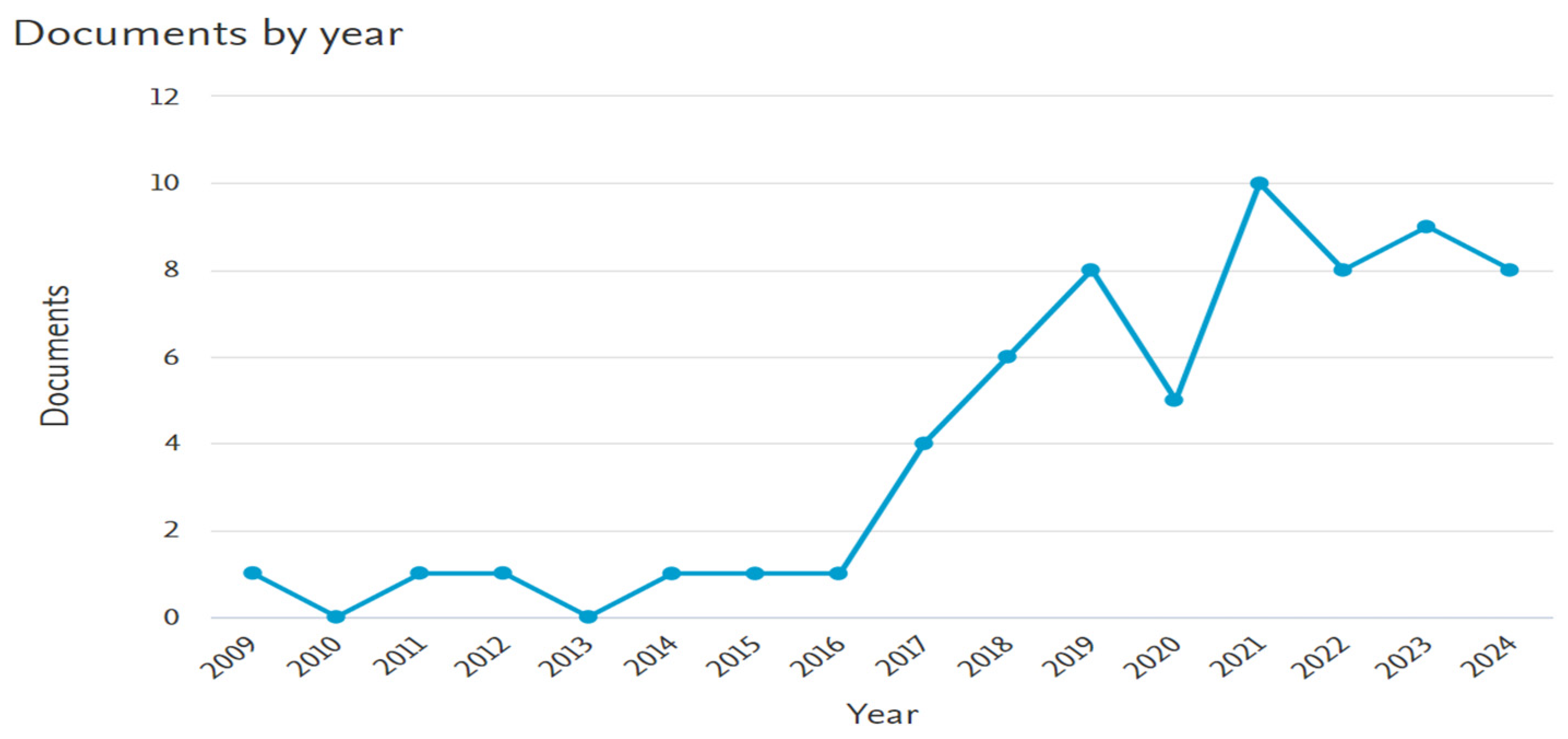

4.3. Publication per Year

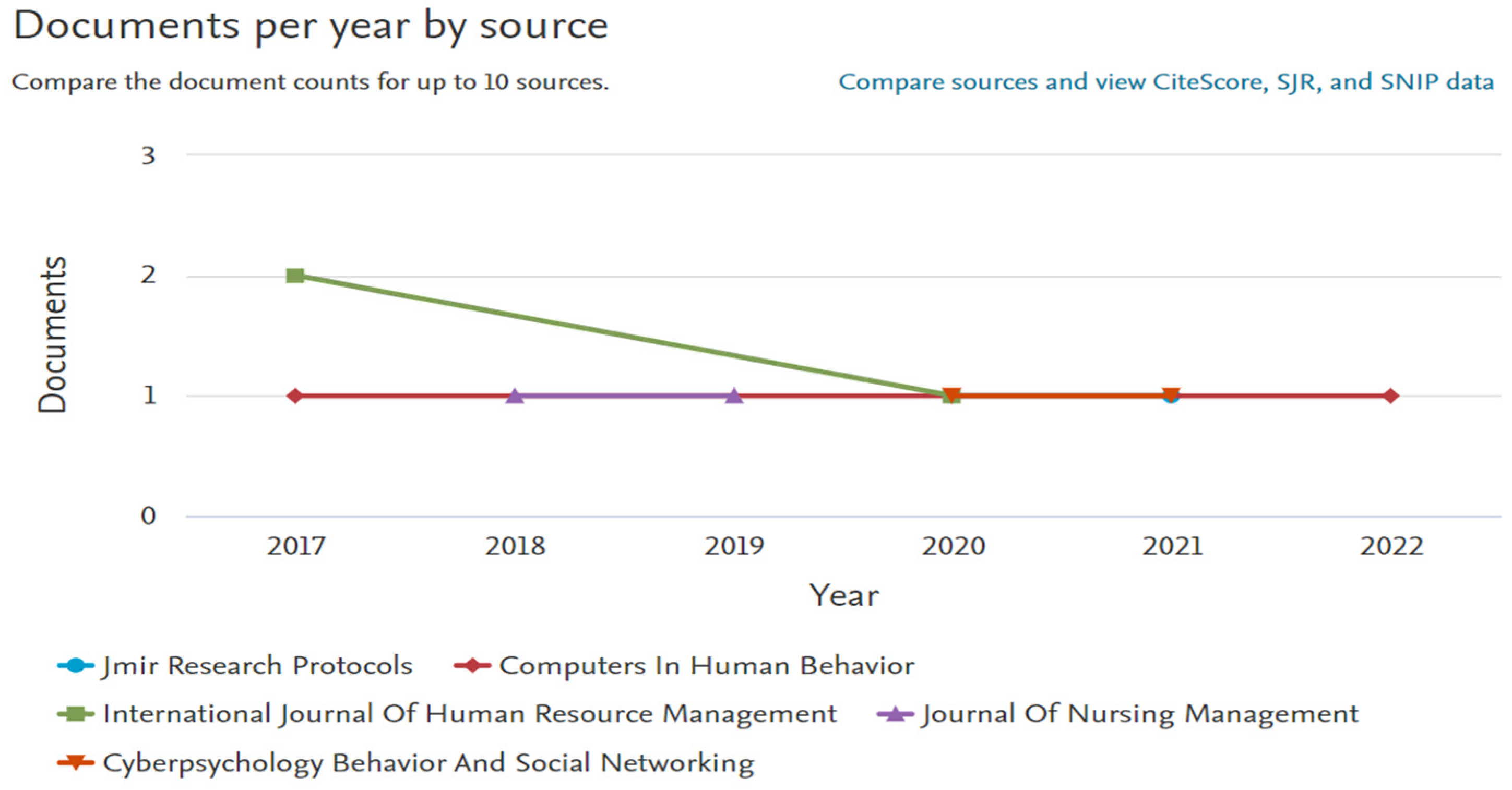

4.4. Publication per Year by Source

4.5. Keywords and Occurrences in Publications

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steenkamp, N.; Kashyap, V. Importance and contribution of intangible assets: SME managers’ perceptions. J. Intellect. Cap. 2010, 11, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegwu, M.E. Employee relations policies and organisational sustainability. Glob. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, N.; Balaji, M. Organisational sustainability scale: Measuring employees’ perception on sustainability of organisation. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2022, 26, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Tencati, A. Sustainability and stakeholder management: The need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, W.F.; Ho, J.A.; Azahari, A.R. The influence of sustainable organisation practices and employee well-being on turnover intention. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 24, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, E.E.; Valcour, M.; Lirio, P. Organisational strategies for promoting work-life balance and well-being. In Work and Well-Being: Well-Being: A Complete Reference Guide; Chen, P.Y., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Samul, J. Spiritual leadership: Meaning in the sustainable workplace. Sustainability 2020, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.; Watson, D.; Nayani, R.; Tregaskis, O.; Hogg, M.; Etuknwa, A.; Semkina, A. Implementing practices focused on workplace health and psychological well-being: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L. Coming clean about carbon: Industries disclose emissions to claim the high ground. New York Times, 20 December 2009; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.K.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Fisher, S.; Russell, S.; Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Lewis, S. Managing workplace bullying and social media policy: Implications for employee engagement. Acad. Bus. Res. J. 2014, 1, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S.; Brake, D.R. On the rapid rise of social networking sites: New findings and policy implications. Child Soc. 2010, 24, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Electronic Dating Violence; Cyberbullying Research Center: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vranjes, I.; Baillien, E.; Vandebosch, H.; Erreygers, S.; De Witte, H. The dark side of working online: Towards a definition and an emotion reaction model of workplace cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K. Cyberbullying. Z. Psychol./J. Psychol. 2009, 217, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, D.C. Workplace bullying and ethical leadership. J. Values-Based Leadersh. 2008, 1, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, T.; Gratton, L. The third wave of virtual work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual teams research: 10 years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities. J. Manag. 2014, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; D’Cruz, P. Cyberbullying at work: Understanding the influence of technology. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 233–263. [Google Scholar]

- West, B.; Foster, M.; Levin, A.; Edmison, J.; Robibero, D. Cyberbullying at work: In search of effective guidance. Laws 2014, 3, 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiamboonprasert, W.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Effect of ethical leadership on workplace cyberbullying exposure and organisational commitment. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 15, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Target experiences of workplace bullying on online labour markets. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizard, L.M. Faculty members’ perceived experiences of cyberbullying by students at a Canadian university. Int. Res. High. Educ. 2016, 1, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, W.; Faucher, C.; Jackson, M. The dark side of the ivory tower: Cyberbullying of university faculty and teaching personnel. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 60, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Farley, S.; Axtell, C.; Sprigg, C.; Best, L.; Kwok, O. Understanding the relationship between experiencing workplace cyberbullying, employee mental strain and job satisfaction: A dysempowerment approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; Sprigg, C.; Axtell, C.; Subramanian, G. Exploring the impact of workplace cyberbullying on trainee doctors. Med. Educ. 2015, 49, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Navigating the extended reach: Target experiences of cyberbullying at work. Inf. Organ. 2013, 23, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannett, A. At work: Cyberbullies graduate to the workplace. USA Today, 5 October 2013; p. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, M.M.; Di Carlo, H.; Caboral-Stevens, M. Workplace cyberbullying exposed: A concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Leidner, D.; Cao, X.; Liu, N. Workplace cyberbullying: A criminological and routine activity perspective. J. Inf. Technol. 2022, 37, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, C.; Campbell, M.A. Cyberbullying: The new face of workplace bullying? CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, M.N.; Alsawalqa, R.O.; Alnajdawi, A.; Aljboor, R.; AlTwahya, F.; Ibrahim, A.M. Workplace cyberbullying and social capital among Jordanian university academic staff: A cross-sectional study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, E.Z.; Isahak, M.; Rampal, S.; Rosnah, I.; Zakaria, M.I. Organisational antecedents of workplace victimisation: The role of organisational climate, culture, leadership, support, and justice in predicting junior doctors’ exposure to bullying at work. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.; Snyman, R. The tangled web: Consequences of workplace cyberbullying in adult male and female employees. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celuch, M.; Oksa, R.; Savela, N.; Oksanen, A. Longitudinal effects of cyberbullying at work on well-being and strain: A five-wave survey study. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 3410–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P.; Agatston, P.W.; Malden, M.A. RURD? The Nuances of Cyber Bullying; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, A.; Oksa, R.; Savela, N.; Kaakinen, M.; Ellonen, N. Cyberbullying victimisation at work: Social media identity bubble approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 109, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.L.; Stich, J.-F. The technostress trifecta—Techno eustress, techno distress and design: Theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Lim, W.M.; Dabić, M.; Kumar, S.; Kanbach, D.; Mukherjee, D.; Corvello, V.; Piñeiro-Chousa, J.; Liguori, E.; et al. Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 2577–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Ali, F. Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute’. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 481–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’cAss, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S. Guidelines for interpreting the results of bibliometric analysis: A sensemaking approach. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 43, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, A.N.M.; Purbasha, A.E. Cyberbullying among youth in developing countries: A qualitative systematic review with bibliometric analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 146, 106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria-Marin, M.; Merigó, J.M.; Baier-Fuentes, H. Knowledge management: A global examination based on bibliometric analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 140, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R. A review of knowledge management research in the past three decades: A bibliometric analysis. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2024, 54, 339–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, R.; Ahmadah, W.A. Exploring bullying behaviours from the perspective of physicians and nurses in Jordanian public hospitals. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2023, 45, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Desrumaux, P.; Hellemans, C.; Malola, P.; Jeoffrion, C. How do cyber- and traditional workplace bullying, organisational justice and social support, affect psychological distress among civil servants? Le Trav. Hum. 2021, 84, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana Sainju, K.; Zaidi, H.; Mishra, N.; Kuffour, A. Xenophobic bullying and COVID-19: An exploration using Big Data and qualitative analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, N.; Forsyth, D.; Tappin, D.; Catley, B. Conceptualising workplace cyberbullying: Toward a definition for research and practice in nursing. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; Axtell, C.; Sprigg, C. Design, development and validation of a workplace cyberbullying measure, the WCM. Work. Stress. 2016, 30, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.H.; Rasmussen, W. Workplace bullying and relationships with health and performance among a sample of New Zealand veterinarians. N. Z. Vet. J. 2018, 66, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, D.; O’dRiscoll, M.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Roche, M.; Bentley, T.; Catley, B.; Teo, S.T.T.; Trenberth, L. Predictors of workplace bullying and cyber-bullying in New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Croxton, R.; Moniz, R. Incivility and dysfunction in the library workplace: A five-year comparison. J. Libr. Adm. 2023, 63, 42–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C.; Chien-Hou, L.; Hwang, M.-Y.; Hu, R.-P.; Chen, Y.-L. Positive affect predicting worker psychological response to cyber-bullying in the high-tech industry in Northern Taiwan. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. “I know it shouldn’t but it still hurts” bullying and adults: Implications and interventions for practice. Nurs. Clin. 2011, 46, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Toth, A.; Morgan, M. Bullying and cyberbullying in adulthood and the workplace. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 158, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.M.; Ross, S.W. Bullying perpetration, victimisation, and demographic differences in college students: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 18, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Parveen, S.; Finne, L.B. Workplace mistreatment and insomnia: A prospective study of child welfare workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, M. Fostering constructive action by peers and bystanders in organisations and communities. Negot. J. 2018, 34, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaller, M.D. The plague of bullying: In the classroom, the psychoanalytic institute, and on the streets. Psychoanal. Inq. 2013, 33, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Su, X.; Bhatti, M.H. Suffering doubly: Effect of cyberbullying on interpersonal deviance and dual mediating effects of emotional exhaustion and anger. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofler, I.R. Bullying, hazing, and workplace harassment: The nexus in professional sports as exemplified by the first NFL Wells report. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I.; Baillien, E.; Vandebosch, H.; Erreygers, S.; De Witte, H. When workplace bullying goes online: Construction and validation of the Inventory of Cyberbullying Acts at Work (ICA-W). Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.S. Unsociable speech: Critical discourses on cyber incivility from inside the non-profit sector in Canada. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 15, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudstra Marit, H.; van Rensburg, E.J.; Visser, M. Learner-to-teacher bullying as a potential factor influencing teachers’ mental health. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2018, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Leidner, D. From improper to acceptable: How perpetrators neutralise workplace bullying behaviours in the cyber world. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, O.F.; Pichler, S. Linking perceived organisational politics to workplace cyberbullying perpetration: The role of anger and fear. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 186, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguz, A.; Mehta, N.; Palvia, P. Cyberbullying in the workplace: A novel framework of routine activities and organisational control. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 2276–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, C. Workplace cyberbullying and its impact on productivity. In Handbook of Research on Cyberbullying and Online Harassment in the Workplace; Salazar, L.R., Ed.; West Texas A&M University: Canyon, TX, USA, 2021; pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Platts, J.; Coyne, I.; Farley, S. Cyberbullying at work: An extension of traditional bullying or a new threat? Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2023, 16, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, G.; Escartín, J. The making and breaking of workplace bullying perpetration: A systematic review on the antecedents, moderators, mediators, outcomes of perpetration and suggestions for organisations. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2023, 69, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Articles | |

| 1 | Ababneh, R. and W.A. Ahmadah, Exploring bullying behaviours from the perspective of physicians and nurses in Jordanian public hospitals. Employee Relations: The International Journal, (2022). 45(1), p. 121–139. [49] |

| 2 | Coyne, I., S. Farley, C. Axtell, C. Sprigg, L. Best and O. Kwok, Understanding the relationship between experiencing workplace cyberbullying, employee mental strain, and job satisfaction: A dysempowerment approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2017 28(7), p. 945–972. [25] |

| 3 | D’cruz, P. and E. Noronha, Navigating the extended reach: Target experiences of cyberbullying at work. Information and Organisation, 2013. 23(4), p. 324–343. [27] |

| 4 | Desrumaux, P., C. Hellemans, P. Malola, and C. Jeoffrion, How do cyber and traditional workplace bullying, organisational justice, and social support affect psychological distress among civil servants? Le travail Humain, 2021. 3, p. 233–256. [50] |

| 5 | Dhungana S., K., H. Zaidi, N. Mishra, and A. Kuffour, A. Xenophobic bullying, and COVID-19: An exploration using big data and qualitative analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022. 19(8), 4824. [51] |

| 6 | D’Souza, N., D. Forsyth, D. Tappin, and B. Catley, Conceptualising workplace cyberbullying: Toward a definition for research and practice in nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 2018. 26(7), p. 842–850. [52] |

| 7 | Farley, S., L. Coyne, C. Axtell, and C. Sprigg, Design, development and validation of a workplace cyberbullying measure, the WCM. Work and Stress, 2016 30(4), p 293–317. [53] |

| 8 | Farley, S., L. Coyne, C. Sprigg, C. Axtell, and G. Subramanian, Exploring the impact of workplace cyberbullying on trainee doctors. Medical Education, 2015. 49(4), p. 436–443. [26] |

| 9 | Gardner, D.H. and W. Rasmussen, Workplace bullying and relationships with health and performance among a sample of New Zealand veterinarians. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 2018 66(2), p. 57–63. [54] |

| 10 | Gardner, D., M. O’Driscoll, H.D. Cooper-Thomas, M. Roche, T. Bentley, B. Catley, B., … & T. Trenberth, Predictors of workplace bullying and cyber-bullying in New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2016. 13(5), p. 448. [55] |

| 11 | Henry, J., R. Croxton, and R. Moniz, (2023). Incivility and dysfunction in the library workplace: A five-year comparison. Journal of Library Administration,2023. 63(1), p. 42–68. [56] |

| 12 | Hong, J.C., L. Chien-Hou, M.Y. Hwang, R.P. Hu, and Y.L. Chen, Positive affect predicting worker psychological response to cyber-bullying in the high-tech industry in Northern Taiwan. Computers in Human Behaviour,2014. 30, p. 307–314. [57] |

| 13 | Kelly, L. “I know it shouldn’t, but it still hurts” bullying and adults: Implications and interventions for practice. Nursing Clinics, 2011. 46(4), p. 423–429. [58] |

| 14 | Kowalski, R.M., A. Toth, and M. Morgan, Bullying and cyberbullying in adulthood and the workplace. The Journal of Social Psychology, 2018 158(1), p 64–81. [59] |

| 15 | Lund, E.M. and S. Ross, S. W. Bullying perpetration, victimisation, and demographic differences in college students: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 2017. 18(3), p. 348–360. [60] |

| 16 | Nielsen, M.B., Parveen, S. and L.B. Finne, Workplace mistreatment and insomnia: a prospective study of child welfare workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 2023. 96(1), p. 131–141. [61] |

| 17 | Rowe, M. Fostering constructive action by peers and bystanders in organisations and communities. Negotiation Journal, 2018. 34(2), p. 137–163. [62] |

| 18 | Smaller, MD, The plague of bullying: In the classroom, the psychoanalytic institute, and on the streets. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 2013. 33(2), p. 144–152. [63] |

| 19 | Syed, N., A.B.A. Hamid, X. Su, and M.H. Bhatti, Suffering doubly: Effect of cyberbullying on interpersonal deviance and dual mediating effects of emotional exhaustion and anger. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022. 13, 941235. [64] |

| 20 | Symons, M.M., H. Di Carlo, and M. Caboral-Stevens, Workplace cyberbullying exposed: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 2021. 56(1), p. 141–150. [29] |

| 21 | Tofler, I.R. Bullying, hazing, and workplace harassment: The nexus in professional sports as exemplified by the first NFL Wells report. International Review of Psychiatry, 2016. 28(6), p. 623–628. [65] |

| 22 | Vranjes, I., E. Baillien, H. Vandebosch, S. Erreygers, and H. De Witte, When workplace bullying goes online: Construction and validation of the Inventory of Cyberbullying Acts at Work (ICA-W). European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 2018. 27(1), p. 28–39. [66] |

| 23 | Williams, K.S., Unsociable speech: Critical discourses on cyber incivility from inside the non-profit sector in Canada. Qualitative Research in Organisations and Management: An International Journal, 2020. 15(3), p. 349–369. [67] |

| 24 | Woudstra Marit, H., E. Janse van Rensburg, M. Visser, and J. Jordaan, Learner-to-teacher bullying as a potential factor influencing teachers’ mental health. South African Journal of Education, 2018. 38(1), p. 1–10. [68] |

| 25 | Zhang, S. and D. Leidner, D. From improper to acceptable: How perpetrators neutralise workplace bullying behaviours in the cyber world. Information and Management, 2018. 55(7), p. 850–865. [69] |

| Country | Document | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 18 | 200 |

| Malaysia | 7 | 53 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 247 |

| Pakistan | 5 | 53 |

| South Korea | 5 | 58 |

| Australia | 4 | 237 |

| China | 4 | 30 |

| India | 4 | 5 |

| Belgium | 3 | 131 |

| New Zealand | 3 | 28 |

| South Africa | 3 | 131 |

| Spain | 3 | 7 |

| Germany | 2 | 8 |

| Thailand | 2 | 15 |

| Ghana | 1 | 0 |

| Indonesia | 1 | 0 |

| Israel | 1 | 0 |

| Japan | 1 | 11 |

| Jordan | 1 | 0 |

| Oman | 1 | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 0 |

| Keywords | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying | 27 | 115 |

| Workplace | 20 | 137 |

| Workplace cyberbullying | 20 | 58 |

| Human | 17 | 132 |

| Bullying | 13 | 82 |

| Humans | 12 | 105 |

| Article | 9 | 84 |

| Workplace bullying | 8 | 31 |

| Adult | 7 | 68 |

| Computer crime | 7 | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Genga, C.A.; Babalola, S.S. Unveiling the Shadow of Workplace Cyberbullying in the Digital Age: A Call for Research in Africa. Businesses 2024, 4, 491-508. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040030

Genga CA, Babalola SS. Unveiling the Shadow of Workplace Cyberbullying in the Digital Age: A Call for Research in Africa. Businesses. 2024; 4(4):491-508. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040030

Chicago/Turabian StyleGenga, Cheryl Akinyi, and Sunday Samson Babalola. 2024. "Unveiling the Shadow of Workplace Cyberbullying in the Digital Age: A Call for Research in Africa" Businesses 4, no. 4: 491-508. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040030

APA StyleGenga, C. A., & Babalola, S. S. (2024). Unveiling the Shadow of Workplace Cyberbullying in the Digital Age: A Call for Research in Africa. Businesses, 4(4), 491-508. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses4040030