Abstract

Research on the career expectations of employees and the potential (mis)match with their lived reality is abundant, yet the research field has paid less attention to the expectation–reality gap of the self-employed. Self-employed people’s attitudes towards work are, however, important for determining business success and persistence. Therefore, research is needed to examine their expectations as well as how self-employed people’s expectations materialize in their experiences. By analyzing in-depth interviews with 19 self-employed workers without employees in Belgium, both desired and undesired career expectations were revealed. After becoming self-employed, these expectations sometimes materialized in reality, in both a positive (e.g., independence and doing what you love) and a negative (e.g., risk and insecurity) sense. Our results also imply that expectation–reality gaps going in two directions exist. We identified positive expectations being met by less-positive experiences (e.g., loneliness, increased responsibility, being unable to do what you like, overestimated financial success, and unavailable or expensive formal support), as well as negative expectations being met by better experiences (e.g., social support between self-employed colleagues). The study signals that the social environment of the solo self-employed (SSE) merits policy attention. Efforts need to be made to create self-employed networks, where professional and social ties can be formed.

1. Introduction

Workers engage in a job because they feel attracted by its anticipated task content, its good hours or good commute, or its security and wage. Other reasons are the expectation to build a network, a career, or to reach self-realization, etc. [1,2]. For waged employees, there is a large tradition of investigating whether those initial job expectations are met in practice [3]. A gap between job expectations and the reality of one’s professional life (i.e., when expectations do not materialize) is termed the expectation–reality gap [4,5]. Such gaps can contribute to stress and negatively affect well-being and job satisfaction [5,6].

For the self-employed, very little research on such matters exists. Nevertheless, for self-employed individuals, especially without employees, work attitudes and experiences are very important factors for determining business success and persistence [7]. In addition, given increasing rates of solo self-employment (SSE) in most high-income countries [8] and its encouragement in many active labor market policies [9], it is valuable to investigate whether and how expectations for (solo) self-employment materialize in reality.

So far, only financial expectation–reality gaps in self-employment have been investigated [10] and researchers here find the self-employed to be over-optimistic [11]. Financial overconfidence, however, could lead to a harsh confrontation with reality and even a quick exit from self-employment [10]. This might explain the high incidence of new business failure [12]. The realization of non-pecuniary expectations has rarely been investigated before. However, non-pecuniary expectations—such as independence, better working conditions, more time for family commitment, job satisfaction, accomplishing something new, gaining status, self-realization, etc.—could form an important additional part of the story [13,14]. Moreover, the realization of non-financial expectations might retain workers in self-employment, regardless of potential financial disappointment [10].

In sum, the expectation–reality gap has rarely been investigated for the solo self-employed (SSE), certainly with regard to non-pecuniary expectations. The current study aims to fill that gap. We first concentrate on self-employed people’s expectations and then their potential deviation from real-life experiences.

1.1. Work Values and Expectations

In this framework, work values and work expectations are relevant. Work values—also termed work orientations or work preferences—deal with people’s general judgements about work and their conceptions of the desirable in that domain [2]. Research has shown that they play a key motivational role in workers’ selection of jobs and entrepreneurship aspirations [15]. Work expectations, on the other hand, relate to a person’s belief about what will happen in the future. While they are similar, there is a conceptual difference between work values and work expectations—i.e., what is expected may not always correspond to what is wanted; reversely, what is valued may not always correspond to what is expected [2,16]. In the case of the self-employed, for example, business failure might be a reasonable expectation (many self-employed people exit within five years [17]); however, this would not be valued or desired by novice self-employed people. People, however, have a propensity towards optimism bias, which means that most people are more likely to overestimate their chances of desirable outcomes than their chances of undesirable outcomes [18,19]. At least, regarding financial expectations, the self-employed are prone to optimism bias [11]. Especially opportunity-motivated self-employed people may have such a bias, since they are attracted to self-employment because of the perceived benefits of self-employment, such as independence, wealth, and satisfaction [20]. However, do they also have potentially undesirable expectations? Therefore, our first research question is to establish which expectations the opportunity-motivated SSEs have, focusing on both desirable and undesirable expectations.

1.2. Expectation–Reality Gaps

Both work values and work expectations have been used to determine job satisfaction [2]. Particularly, two research traditions emerged. One places value on discrepancies between expectations and actual experiences, while the other places value on discrepancies between desired expectations and actual experiences. The first tradition, originating from McClelland et al. [21], argues that an expectation–reality gap, i.e., when an expectation fails to materialize, can contribute to stress and therefore negatively impact well-being and satisfaction [5,6]. Nevertheless, the theory has been criticized because there is little reference to the desirability of one’s work expectations [5]. The second tradition takes that critique into account [16]. If an expectation–reality gap matches one’s work values (i.e., better than expected), then the gap creates satisfaction. Conversely, if the gap is in the direction of what one disvalues (i.e., worse than expected), that will create dissatisfaction. For the second objective of this study, we will incorporate the two traditions by investigating the extent to which self-employed people’s (desirable and undesirable) expectations match or deviate from their actual experiences. We will focus particularly on the feelings and emotions emerging from such potential expectation–reality gaps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The population of this study consists of solo self-employed workers (i.e., without employees) (SSEs) living in Flanders (Belgium). They were novice self-employed (1 month to 3.5 years in self-employment) meaning they had no long prior self-employment experience [22]. This allowed us to inquire about both expectations and experiences of self-employment. Respondents were recruited during start-up events organized by a Flemish non-profit organization for the self-employed. We approached the attendees, introduced them to the research, had a short chat about their business, and asked whether they would be willing to participate in an interview at a later time. In total, 58 attendees agreed to participate. Between recruitment and the actual interview there was, however, considerable drop-out: respondents could not be reached via their contact info, they were no longer interested, no longer self-employed (or eventually decided not to become self-employed), or on reflection, did not fit the study profile based on criteria such as time in self-employment or not having employees. Finally, 19 SSEs were interviewed.

Table 1 presents a description of the informants. The sample varied regarding gender (9 male, 10 female) and age (22 to 49 years old), and type of activities (e.g., consultancy, informatics, sales, landscaping, design…). The sample included main profession self-employed (N = 8) and hybrid self-employed (N = 11) (i.e., combined with waged employment, unemployment, or education). All respondents were opportunity self-employed [20].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the interviewees.

2.2. Field Work and Analyses

The data was collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews. Qualitative research can uncover respondents’ lived experiences, motivations, and the meanings they give them, which are difficult to capture in quantitative research [23]. The interviews consisted of open-ended questions and more targeted questions about predetermined topics. The questions referred to expectations about self-employment, the start-up and working experience, and the future. In relation to working experiences, respondents were asked about dimensions of job quality (i.e., the conditions and content of work as well as the conditions and relations of employment [24]). This rendered us a holistic view of the SSEs’ expectations and work experiences. During the interviews, we applied a phenomenological approach in which the perceptions, opinions, and feelings of the participants received much attention [25]. The phenomenological approach applies well to studying entrepreneurs and their behaviors and helps us to grasp the richness of the entrepreneurial life world [25]. Furthermore, the phenomenological approach is well suited for developing new insights into existing theories.

Interviews were held between February and June 2020. Three interviews were held face-to-face, while all other interviews were held online due to COVID-19. They were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The length of the interviews varied between 42 and 94 min. Informed consent was obtained before each interview.

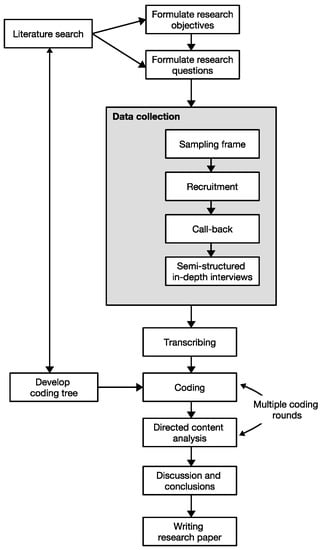

We applied directed content analyses [26], using as a deductive point of departure a coding scheme which was inspired by theories about expectations and motives for choosing self-employment (see Table 2) and the dimensions of job quality [24]. To allow for new insights, emerging topics could modify the initial coding structure [26]. The reported expectations in Section 3 may therefore go beyond the expectations that were initially laid out by the literature. See Figure 1 for a diagram of the methodological steps.

Table 2.

Common expectations of self-employment from the literature.

Figure 1.

Research methodology diagram.

3. Results

Most expectations about self-employment, as mentioned by our informants, could be divided into six groups. They were mentioned after an open question about their expectations, or after a question in which the interviewer specifically probed into other expectations that were not mentioned spontaneously, but which the entrepreneurship literature has defined as important for becoming self-employed (see Table 2). Of the six reported expectation groups, four were considered valued and desirable (e.g., expecting to (1) become independent and autonomous, (2) be able to do what you love and achieve self-realization, (3) achieve financial success and earn a livable wage, (4) receive formal support and professional advice). Two other expectation groups were perceived as potentially undesirable (e.g., expecting (5) insecurity and risk and (6) distrust and competition between self-employed colleagues). Each group of expectations is discussed below and confronted with actual experiences (expectation–reality gaps) in self-employment.

3.1. Expectation 1: To Become Independent and Autonomous

Independence, autonomy, and flexibility were prominent themes among our informants’ expectations. People chose self-employment because they expected to find greater freedom, autonomy and independence compared to waged employment. As such, self-employment has been argued to fulfill a basic psychological need for autonomy that is critical to human functioning and well-being [28]. In our sample, the value that was placed on independence was closely related to deciding one’s own rhythm and the ability to determine their own working time arrangements. Marc for example, expected that self-employment would give him the ability to freely set his own work schedule:

“Maybe to be able to do my own thing. That might sound a little strange, but it is that, just being able to do things. I mean, you don’t just do what you want, because your customers are still your boss. But making your own schedule. That means a lot to me. To not to be tied to that rhythm. That is worth a lot too. To be able to decide for yourself when it is necessary to work and when it is not”.(Marc, male, landscaper, 34)

Expectations of independence were often discussed in contrast to experiences as a waged worker. Experiences as employees made many of our respondents feel dissatisfied and made them feel their situations could be improved if they became self-employed. They expected that self-employment would make them fully independent and involved in every step of the work process, contrary to the task fragmentation they experienced as employees.

For many, expectations regarding independence (to set one’s own rhythm and to be part of every step) were achieved when becoming self-employed. Jasmijn, for example, felt that solo self-employment matched her expectations of independence.

“At the end of the day, I am the one who gets to make the decisions, and it doesn’t matter if someone says “no, that costs too much, rethink that, you should look into all these other options first”. It goes a lot quicker. At least, that is my feeling. While, as an employee, even though I was a manager, you are held back by all these strategical decisions and all the political games around that whereas now, there is total freedom to make your own choices”.(Jasmijn, female, clothing designer, 30)

In terms of escaping task fragmentation, Kathleen explained how being self-employed made her responsible for the whole task, which gave her a feeling of achievement.

“Before, when I was working on something, it was teamwork. It is still a bit like that because I sometimes work together with someone on the visual side, but still you have much more of a feeling like: “Look, the thing over there, or what I’m holding right now, I made that, or I did that”. And there were not 27 strategists involved first. You know, you have a lot more of the process in your own hands, so the final result is also, yeah, more yours. So, at those moments, I really felt, “look, well done!” {…} I am a lot more involved from A to Z, which also implies that there are a lot of other things that otherwise, in a large company, other people would have been responsible for. And that gave me a much bigger drive!”.(Kathleen, female, copywriter, 40)

The above accounts show that expecting independence can provide a strong incentive for becoming self-employed. Most of the time, these expectations come true, which leads to satisfaction and feelings of achievement. Nevertheless, some did experience an expectation–reality gap and felt that increased independence also had indirect, unwanted consequences, such as increased pressure and stress from being more responsible:

“If I start at 8, that’s fine, if I start at 7, that is my decision. So, in that sense, it is a real relief. But, on the other side, it is also all my responsibility. But I try not to think about that too much. Because otherwise, it will really cause stress. You must be able to put things in perspective. But still, you must be able to manage it all yourself and control it all yourself”.(Matteo, male, furniture designer, 25)

Most informants might have expected that self-employment would bring larger responsibility. However, they did not mention it when explaining their expectations. Perhaps, as Matteo’s testimony makes clear, our respondents preferred not to think about these more stressful factors when becoming self-employed.

The biggest gap, however, between expected independence and how it materialized came from social isolation. Gaby missed the social contact from her corporate employment the most:

“That is the only thing I have missed so far, after my resignation, my colleagues, that is certainly true. In my last job, I was also alone at the office, so I didn’t have anyone with me. So, I was used to it, but yeah, still, I notice, it is lonelier. {…} What I miss the most between now and life as an employee, that’s having nice colleagues”.(Gaby, female, data systems trainer, 44)

Social isolation was even mentioned as a reason to return to waged employment. Kurt, who became a self-employed data consultant, but later returned to waged employment, stated that the availability of a sounding board (i.e., someone to bounce ideas off from and talk to when unsure about decisions), might have meant a different outcome for him.

In sum, for the SSEs, independence was one of the most crucial factors in becoming self-employed. Oftentimes this independence was achieved. Yet, our informants also voiced discrepancies related to increased responsibility and social isolation.

3.2. Expectation 2: To Be Able to Do What I Love, Achieve Self-Realization and Purpose

Many embark on self-employment to pursue self-directed goals, to challenge oneself in creative and interesting jobs, and to achieve a personal vision [13,27]. In our sample, expecting to be able to do what you love and achieving self-realization also emerged as a major subtheme. Many of our informants described their choice as the completion of a fundamental life goal. In particular, becoming self-employed offered a road towards achieving something they would not be able to as an employee and was often guided by passion. Ellen, for example, said:

“What I expected from being self-employed? How should I put this. Meaning? The fact that I could do something for other people. Which would make them more aware about the beauty of nature, and of how important greenery is for their mind-set, their well-being. But mostly, also for myself, that the fact that I am walking around here, that it has a purpose. That I can pass on my knowledge or insight. Help people, but only if they want to be helped. {…}. I just want to be happy really, and that’s why this meaning is so important for me”.(Ellen, female, life coach, 42)

Otherwise, self-employment is a purpose in itself. Gaby remembered having had a predisposition towards self-employment for years; however, finding an interest in cryptocurrency influenced her jump.

“For years, I wanted to become self-employed, but I just didn’t know as what, and with this is just made sense. This is really ‘my thing’. I find this technology so fascinating and what it all can mean for society, the decentralized currency. It has so many advantages for society. All decentral applications have a lot of advantages for society, and that really attracted me to it. I have always had a thing for IT and pioneering technology. So, this, this is what I have passion for. I didn’t have passion for my previous work”.(Gaby, female, data systems trainer, 44)

For many, the expectation that self-employment would lead to self-realization and happiness, to a large extent, became reality. Anneleen noted:

“You are working on what you like to do, and that gives a feeling of satisfaction. You are working on your passion, so I think that yes, that is a really positive thing for your mental well-being”.(Anneleen, female, leather accessories designer, 32)

Nevertheless, previous research has also cautioned against self-realization and the execution of one’s passion as one’s main motives for choosing self-employment [29]. Sometimes, actual experiences are intrinsically poorer than expected, leading to expectation–reality gaps. In our sample, we found two of such gaps.

The first expectation–reality gap related to spending a lot of time on non-core, less-liked activities. Many became self-employed for the interesting work content, but not a lot of time was spent on the activities they really loved. As Jasmijn mentioned:

“I didn’t think, or, I did think, it would be a whole lot more creative. Because you start a creative job, but then there are many other things involved. A lot, like, yes, drafting contacts, building your network, and investing in marketing. It seems silly, but social media, that costs a lot of time to do that all yourself, but it is necessary. Because I notice that in the weeks I’m not as active, there is a relapse in purchases and messages. So, the creative, I think, I think it is 50/50. So, yeah, maybe I thought it would have been more about only the fun stuff”.(Jasmijn, female, clothing designer, 30)

The second gap revolved around balancing clients’ wishes and one’s own. This was the case for Matteo, who remembered an assignment in which his clients wanted him to complete a wood joinery job, but he was more passionate about designing furniture. Matteo and his clients interpreted his activities differently, but Matteo found it hard to say “no”, especially in the beginning.

“I had an assignment, and they had seen some of my work, that I had designed and manufactured myself. And I thought they would want something similar, but that was also my first, real experience with clients. And it turned out that they wanted something purely about wood joinery, like an inner door, and I thought, that’s not where I want to head, and I don’t know if I can do that. But at that point, I did take on the job”.(Matteo, male, furniture designer, 25)

Matteo further explained: “Since then, I made the decision to dare to say no”. Standing your ground against customers often depended on the financial state of the business. When the business was going well, many actively safeguarded their self-directed goals; however, when faced with financial insecurity, this appeared to be more difficult.

In sum, self-employment as a way towards self-realization, happiness, and fulfilling passions is often met with the reality of compromising with clients, dealing with financial insecurities, and dealing with the more practical sides of running a business, creating discrepancies between expectations and actual experiences.

3.3. Expectation 3: To Achieve Financial Success and Earn a Livable Wage

Other expectations for self-employment were higher earnings and financial security [13]. Over-optimism about financial expectations has been documented before among the self-employed [10]. However, while financial expectations did emerge in our interviews, the SSEs mostly talked about it to stress that financial factors were not their main goal. Senne expands on this:

“An expectation that most self-employed have, which I don’t have, is the financial aspect. Earning more. And for me that is absolutely not the reason why I became self-employed because it really is, the reason is, being able to make my own choices. And that comes back to flexibility, but the financial side was not a factor, or expectation at all”.(Senne, male, computer science consultant, 28)

Such accounts imply that the SSEs put most emphasis on the intrinsic value of their work. However, while informants did not always expect that their self-employed endeavors would immediately lead to financial success, they did hope to live from their self-employed income. Glenn’s account is exemplary:

“I did talk about that with my wife, financial expectations. Everyone would like to make a lot of money and maybe drive a nice car, or have a swimming pool in their garden, but it wasn’t a priority for me. I just hoped that I would be able to live well from it {…}. Uh, but I have to say, I didn’t do it for the money. That might sound strange, but no”.(Glenn, male, business in chemical coating, 49)

The self-employed were thus cautious to express their expectations for their financial future. Nevertheless, asking our informants about their negative experiences, we found that maybe there were financial expectations that did not materialize. Kurt’s account illustrates this. He overestimated the demand for his service and found less job opportunities than expected:

“Because the demand for data science is very large, and the supply is very small. So, I thought, okay, this is the right time. But it has not turned out quite like that”.(Kurt, male, data science consultant, 29)

It can be hard to realize that such expectations failed to materialize. Anneleen realized this also:

“Certainly, in the beginning, I had very unrealistic expectations about how many purses I would produce and sell every month. And when you see, in practice, how many I actually made and sold in a month, it was a lot less”.(Anneleen, female, leather accessories designer, 32)

In sum, regarding financial expectations, we found varying perspectives. Some had no financial expectations at all, while others mostly expected to earn a livable wage. Regardless, we found expectation–reality gaps relating to an overestimation of demand or capacity.

3.4. Expectation 4: Formal Support and Professional Advice

The fourth group of expectations related to support when becoming self-employed. Research shows that (novice) self-employed people often do not understand the legal form and requirements of their business, but instead rely on the advice of specialists [30]. Advice from lawyers, accountants, other entrepreneurs, and business support organizations can help the self-employed to recognize opportunities and changes in laws and regulations, and to gain access to knowledge [31]. In particular, for the SSEs who work by themselves, the role of professional bodies and support networks is important [32].

Our respondents mentioned two actors from whom they expected support: (1) public organizations and (2) private professionals (accountants, other self-employed people). For Sara, this even made her take the plunge:

“I think the idea that you are not on your own. That, if you need support, even if it is just an e-mail, or six month’s free membership for UNIZO {Flemish, non-profit business support organization}. It is silly, you make very little use of it, but you do know that, okay, I can ask a question if I want to. I can ask my accountant questions or people who have been self-employed for a long time. That were very important things to me, that you can connect, that it isn’t always nothing. {…} But, if you have low risks and the fact that you can go anywhere with your questions, that was important to me to eventually say “Okay, I am going to do this””.(Sara, female, interior designer, 47)

Many of our informants, however, were disappointed by the actual support they received. First, an expectation–reality gap regarding public support infrastructures was identified. Ellen, for example, described how she felt that self-employment was highly encouraged by public support organizations; however, when she became self-employed, there was no real structure in place to support her.

“I have the feeling that, and it might just be a feeling, but that they say “yeah, go ahead”, but actually, there is not a lot of support or capacity in place really to support you. It’s like they say, “make up your own plan and make sure you get out of that pool of employment seekers, so we do not have to give you money anymore”. And then you just stumble further”.(Ellen, female, life coach, 42)

The expectation of receiving support from private actors, however, did materialize. See Senne’s account:

“Experiences? Which were positive? The help everyone is offering or was offering. {…} for example, your accountant, if you send him an e-mail, he will figure it out for you. Or the social security fund, even if you send them just an e-mail, they will investigate. Or really, the fact that, it is really encouraging and reassuring to know that the social security fund, that when you ask them something, they will do it for you”.(Senne, male, computer science consultant, 28)

However, this form of support also had a high monetary cost, leading to another expectation–reality gap. Anneleen explains:

“I think that generally, if you become self-employed, you get a lot of advertisements about companies, and services that could help you. But you have to pay for them all, and you simply do not have money for that at the beginning”.(Anneleen, female, leather accessories designer, 32)

In sum, asking for advice was considered valuable among almost all the informants. However, their experiences with the availability of public support structures and the financial cost of private, professional advice made up these expectation–reality gaps.

3.5. Expectation 5: Insecurity and Risk

Their expectations, however, were not all positive (i.e., things they did not desire but did expect). Expecting insecurity and risks emerged as an important theme. Particularly, insecurity was often considered the price of being self-employed [33]. In our research, Amir’s testimony is striking:

“From the moment you apply for your VAT-number, you initiate a risk. And from that moment, you know only two things for sure: you’ll pay taxes, and well, that one day, you’ll die. Everything else is an unknown”.(Amir, male, used cars retailer, 35)

Our interviewees did show a willingness and perceived self-efficacy (i.e., “initiating and persisting at behavior under uncertainty” [34] (p. 418)) to take on these risks. This is particularly true when potential rewards are involved, as Senne said: “There are risks, insecurities, but those who do not take their chances, do not win”. In a certain sense, many of our self-employed participants had internalized meritocratic principles. They considered failure their own fault, but potential success was also attributed to their own merit and willingness to take on risk. Frederik explains:

“If you do something with more risks, it is just more exciting. Because it can go wrong, it can fail. You can lose face, you can lose customers, you can really fail. But if you, do it really well, and you do it really, yes, really well, then things can just go even better”.(Frederik, male, founder of tutoring agency, 28)

Eventually, when they became self-employed, they did experience insecurity and, despite being expected, this created stress. As Charlotte describes:

“You can always make a business plan and a financial plan, and try to predict how much you’ll earn, but you don’t know. And patients have to find out about you, people need to get to know you, so I found that hard to predict. I did have stories from friends who said that it was possible, and who were transparent in their own numbers, and that helped. But on the other hand, we work in a completely different region, so yes, it was really difficult to estimate and that gave me a lot of stress”.(Charlotte, female, hearing aid consultant, 33)

Many of our informants also took steps to reduce insecurity (e.g., building a financial buffer, diversifying economic activities, depending on a partner with a stable income, or becoming part waged employed). However, these strategies contrasted with some of the other desired expectations they had (e.g., liberty, autonomy, and success), creating new expectation–reality gaps. Ellen, for example, partially relied on her partner’s income; however, this was difficult to combine with her desire for independence:

“It is true that I do struggle with not having a decent income anymore. I do feel it, that it plays a part. I do not like to be dependent on someone else. At this moment, that is not the case, but I feel that it is coming, and I feel that it is troubling me”.(Ellen, female, life coach, 42)

Anneleen was in waged employment aside from her self-employed activities to reduce insecurity and supplement her income. By doing so, however, she also felt she reduced her chances of success:

“Of course, I don’t have to earn anything because I have another income, right? That has its advantages and disadvantages. Because you also don’t experience the pressure of having to earn money. That is an advantage and a disadvantage, because you might, I don’t know, perform less perhaps”.(Anneleen, female, leather accessories designer, 32)

The SSEs in our sample appeared well aware of the risks and insecurity when they were seeking self-employment. Many also experienced insecurity once they became self-employed. In addition, navigating around insecurity, in turn, caused discrepancies with other desired expectations, such as independence and success.

3.6. Expectation 6: Distrust and Competition between Self-Employed Colleagues

Many of the interviewees also expected distrust and competition between self-employed colleagues, which could have been problematic for social support [35]. This expectation, however, did not materialize, which means there was a positive expectation–reality gap. Jasmijn acknowledged this:

“Building a network, with other entrepreneurs, and the support you receive from other entrepreneurs. I always thought it would be a very competitive world. But actually, that is not the case at all, or at least, not like I thought it would be”.(Jasmijn, female, clothing designer, 30)

For SSEs, having self-employed colleagues generally meant a lot. Communication, support, and guidance from these colleagues helped them to develop themselves and gain confidence. Kathleen explained how talking to other, senior, self-employed people made her feel more at ease.

“Where I worked previously, there were also a couple of freelancers and self-employed persons, who were working in similar jobs. So, I asked them a lot of questions like “How does that work?”, “How do you do that?” or “What do you do with that?”. And then I felt like “ah okay”, they still have the same questions, and they still have the same insecurities about what they will do next month, even after all these years”.(Kathleen, female, copywriter, 40)

Furthermore, good contact with self-employed colleagues also reduced insecurity. Some explained that when business was slow, they could work for other colleagues in the same occupational field (subcontracting) or gain new clients through referrals. Matteo explained how he planned to combine part-time self-employment with part-time waged employment to have more security. However, when he could not find a waged job, he found security through self-employed colleagues:

“I had made a list of people to follow on Instagram whose profiles interested me, and who were doing similar things to me. So that, if needed, I could help them, as a freelancer. So that at least, I had some sort of back-up. Well then now, today for example, I worked as a subcontractor for someone that my brother knew. He lives fairly close by, and I’ve talked to him before and he said, “if you do not have enough work, you can always ask if I have some”. So that meant I had some type of back-up, if a project falls through, I can always go to him”.(Matteo, male, furniture designer, 25)

Contrary to their initial expectations, the self-employed received much support from self-employed colleagues. Osnowitz [36], in her influential sociological analyses of contract workers, found something similar: networks of self-employed people can act as both networks of employment and as buffers from social isolation.

4. Discussion

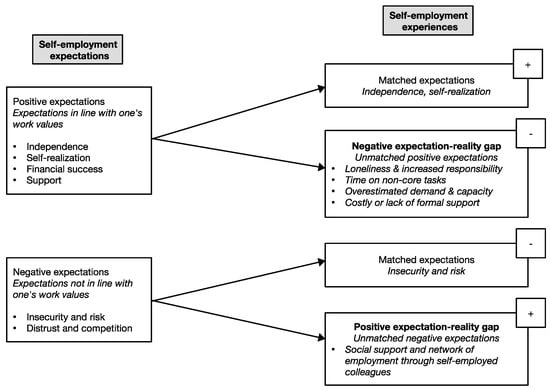

The purpose of this study was to fill the research gap that exists on the expectation-reality gap for the solo self-employed (SSE), concentrating on both desired and undesired expectations and how they do, or do not, materialize in real-life experiences. To a certain extent, expectations for self-employment did materialize, both in a positive (e.g., self-employment involved independence and doing what they loved) and in a negative (e.g., self-employment involved risk and insecurity) sense. Nevertheless, our results also found expectation–reality gaps going in two directions: we identified negative discrepancies, which were positive expectations being met by less-positive experiences (e.g., independence created loneliness and increased responsibility, doing what you love was not always possible, financial success was often overestimated, and formal support structures were either unavailable or involved a high cost), and positive discrepancies which were negative expectations being met by better experiences (e.g., social support being better than expected) (see Figure 2 for a visual summary of the findings). These findings have implications for theory on self-employed people’s career expectations and experiences, as well as practical implications for policymakers and stakeholders.

Figure 2.

Visual diagram of main findings.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

Based on research about optimism bias [18,19], we assumed that the solo self-employed (SSEs) would mostly have positive expectations. Our findings matched those predictions partially. Indeed, SSEs had positive expectations for their future self-employed endeavors, mostly regarding autonomy and independence, achieving self-realization, financial sustainability, and the availability of public and private support structures. Nevertheless, our study also adds nuance: many of our interviewees also had a rather realistic mix of expectations. Aside from expecting things they desired, they also expected potentially undesirable aspects of self-employment. They expected risk and insecurity, and distrust and competition.

Previous studies have shown that individuals’ career expectations, however, are not always accurate [37]. Therefore, we also investigated how expectations did or did not materialize in lived experiences. To some extent, both desirable and undesirable expectations about self-employment were met. As shown in previous research, self-employment was characterized by high levels of independence, skill discretion, and high intrinsic work value [38], but also more risk [39] and insecurity [40]. However, not all portrayed expectations were met in self-employed people’s lived professional lives. Both negative and positive variants of the expectation–reality gap were found:

First, the study revealed that SSEs’ working life can be very lonely, more so than expected, matching worldwide concerns that self-employed people, especially those who work from home, are at risk for physical and mental health hazards due to social isolation [40]. On the other hand, this study also found a positive expectation–reality gap regarding finding more social support than expected among self-employed colleagues. Help-seeking from knowledgeable, more experienced others can be a valuable coping skill commonly used by the self-employed [41].

Second, it has been amply proven that passion about work has strong motivational potential and can drive entrepreneurial decisions [42]. Doing what you like as well as being your own boss are valued beyond material outcomes by most self-employed people. This is in line with the theory of procedural utility (i.e., the assumption that the entrepreneurs gain utility and see value in the process of “being and entrepreneur” aside from the outcome of entrepreneurship) [43]. However, in practice, the self-employed are not always able to dedicate time to what they find enjoyable. These expectations thus have a high potential for disappointment.

Third, many overestimated the potential financial successes. This aligns with evidence on the optimism bias in pecuniary expectations for self-employment [11]. The expectation of financial rewards generally pulls individuals into self-employment, but also a lack of actual financial rewards can push them back out of it [42]. Not a lot of our respondents spoke of exiting self-employment; however, future research should investigate when negative expectation–reality gaps reach a tipping point for the self-employed to seek another career path.

4.2. Practical Implications

These findings also have implications for self-employed workers, policy makers, and public support organizations. The study showed that many SSEs, especially those who work from home, suffer from social isolation. Many of our informants actively tried to counter these experiences of social isolation by renting a spot in co-working infrastructures or by taking on on-location jobs with other self-employed people. These are good strategies to tackle loneliness and social isolation [41]. Many SSEs also valued support and guidance from their self-employed colleagues. Non-profit organizations should therefore increasingly encourage collaboration and connection among the self-employed. Currently, self-employed people’s initial expectations of competition might cause delays for the newly self-employed to ask for help when it is needed. Promoting networks of employment [36] may help in making sure that the self-employed ask for help sooner and survive periods of financial difficulty more easily. Non-profit organizations and policymakers could set up hubs for self-employed workers who need workspaces (co-working spaces, joint ateliers, enterprise areas) to encourage and stimulate mutual contact.

Public support infrastructure and professional advice are also crucial in preparing for self-employment and perceived public support plays an important role in determining people’s attitudes towards self-employment [44]. However, in our interviews, we found that actual support from public support organizations is limited, and that there is a large financial barrier to receiving support from private support actors. This implies the need for more substantial and more affordable support programs, e.g., pro-deo bookkeeping or accountancy services [45].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

We identified two forms of bias in our investigation, specifically regarding the lack of importance of financial expectations: financial statements are often subjected to social desirability bias (i.e., the propensity of respondents to engage in socially desirable responding and, for example, to deny or underreport characteristics that are often subject to disapproval) [46,47] and retrospectively asking about expectations can cause self-deceptive bias (i.e., a defense mechanism in which individuals reject negative information about the self) [46]. Combined, these two forms of bias lead to expectation adjusting, whereby individuals adjust their expectations based on what they are experiencing, and thus set more achievable goals [48]. This might explain why financial motives were considered unimportant when asking retrospectively about initial expectations but seemed more important when asking about experiences. However, focusing on novice self-employed people, we tried to avoid recollection bias as much as possible. Furthermore, research generally finds that motives for entrepreneurship (for self-employed workers) as well as work orientations (for all workers) remain relatively stable over time [49,50].

A second limitation is that most of the interviews were held during the first nationwide COVID-19 lockdown in Belgium. While it is known that self-employed people were affected by policy measures aimed to contain COVID-19 [51], most of our respondents remained relatively unaffected in terms of direct consequences. This was the result of the type of self-employment in our sample, which was mostly service-based, could be performed virtually, or had no physical establishment that was required to be closed. Only a few of them noted indirect consequences and financial losses because their main clients (being businesses themselves) did have to stop their activities. Others indicated that they experienced benefits from the COVID-19 situation because their product was particularly adaptable to the situation, because of the “shop local” movement, or because time was freed up for their self-employed activities after having been put on temporary unemployment in their waged job (for hybrid self-employed). Nevertheless, the lockdown might have (negatively) affected how the social working environment was experienced. Future research should try to disentangle whether social isolation has always been a negative side effect of solo self-employment, or whether this was attributable to the COVID-19 measures.

Additionally, our study group consisted mostly of opportunity entrepreneurs. However, this biased group of well-prepared novice self-employed participants might show an underestimation of the expectation–reality gaps among other types of self-employed people (i.e., those in a more precarious situation of necessity self-employment). Future research should broaden the scope towards that group.

Finally, we would like to cast light on the implications of using proxy variables for investigating the social working environment of the self-employed. In most survey research, the social working environment is either not considered (i.e., based on the assumption that they do not have colleagues or bosses on the work floor) or assessed using inappropriate proxy indicators designed for waged workers (e.g., “do you receive support from colleagues” [52]). We feel that in the future researchers should include the social working environment of the self-employed in surveys using questions adapted to their specific reality (e.g., inquiring into contacts with fellow self-employed people or public and private support actors).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this qualitative study adds nuance to existing findings about mostly optimistic novice self-employed people. It finds both desirable and undesirable future expectations and identifies positive and negative expectation–reality gaps. The study signals that especially the social environment of the SSE merits more research and policy attention. Efforts need to be made to ensure that SSEs who need it become part of self-employed networks to receive professional advice as well as social support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G., D.D.M. and C.V.; Formal analysis, J.G.; Funding acquisition, C.V.; Investigation, J.G.; Methodology, J.G. and K.B.; Supervision, D.D.M. and C.V.; Writing—original draft, J.G.; Writing—review and editing, K.B., D.D.M. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Belgian Science Policy Office (Belspo, Brain-project SEAD 2020-23, contract number B2/191/P3/SEAD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Sciences of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (ECHW-204; 25/11/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Written, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Furåker, B.; Håkansson, K. Work Orientations; Furåker, B., Håkansson, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Work Values and Job Rewards: A Theory of Job Satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achnak, S.; Vantilborgh, T. Do Individuals Combine Different Coping Strategies to Manage Their Stress in the Aftermath of Psychological Contract Breach over Time? A Longitudinal Study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 131, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.C. Job Satisfaction, Marital Satisfaction and the Quality of Life: A Review and a Preview. In Essays on the Quality of Life; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.C.; Artz, K.W. Determinants of Satisfaction for Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Shier, M.L. Profession and Workplace Expectations of Social Workers: Implications for Social Worker Subjective Well-Being. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2014, 28, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schummer, S.E.; Otto, K.; Hünefeld, L.; Kottwitz, M.U. The Role of Need Satisfaction for Solo Self-Employed Individuals’ vs. Employer Entrepreneurs’ Affective Commitment towards Their Own Businesses. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Stel, A.; van der Zwan, P. Analyzing the Changing Education Distributions of Solo Self-Employed Workers and Employer Entrepreneurs in Europe. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Egert, B.; Fulop, G.; Mourougane, A. To What Extent Do Policies Contribute to Self-Employment? OECD Economics Department Working Papers: Paris, France, 2018; p. 1512. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, C. Financial Optimism and Entrepreneurial Statisfaction. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2017, 11, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechat, T.; Torrès, O. Stressors and Satisfactors in Entrepreneurial Activity: An Event-Based, Mixed Methods Study Predicting Small Business Owners’ Health. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 32, 537–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Greene, F.J. The Effects of Experience on Entrepreneurial Optimism and Uncertainty. Economica 2006, 73, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.M.; Gartner, W.B.; Shaver, K.G.; Greene, P.G. The Career Reasons of Minority Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Henley, A.; Latrielle, P. Why Do Individuals Choose Self-Employment? IZA Discussion Papers: Bonn, Germany, 2009; p. 3974. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, C.M.; Sortheix, F.M.; Obschonka, M.; Salmela-Aro, K. What Drives Future Business Leaders? How Work Values and Gender Shape Young Adults’ Entrepreneurial and Leadership Aspirations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 107, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What Is Job Satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. Is Self-Employment Quality Work? In The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.C. Multiple Discrepancies Theory (MDT). Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 16, 347–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, E.B.; Mohamed, E.B.; Dana, L.P.; Boudabbous, S. Does Entrepreneurs’ Psychology Affect Their Business Venture Success? Empirical Findings from North Africa. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 921–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, J.E.; Cristi, O.; Naudé, W. Entrepreneurship and Subjective Well-Being: Does the Motivation to Start-up a Firm Matter? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 127, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C.; Atkinson, J.W.; Clark, R.A.; Lowell, E.L. The Achievement Motive; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Acs, Z. Age and Entrepreneurship: Nuances from Entrepreneur Types and Generation Effects. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 773–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Researcha; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Houtman, I.L.D.; Vanroelen, C.; Kraan, K.O. Increasing Work-Related Stress in the Netherlands and Belgium: How Do These Countries Cope? In Organizational Stress Around the World; Sharma, K.A., Cooper, C.L., Pestonjee, D.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasinghe, D.; Aluthgama-Baduge, C.; Mulholland, G. Researching Entrepreneurship: An Approach to Develop Subjective Understanding. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 866–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assarroudi, A.; Heshmati Nabavi, F.; Armat, M.R.; Ebadi, A.; Vaismoradi, M. Directed Qualitative Content Analysis: The Description and Elaboration of Its Underpinning Methods and Data Analysis Process. J. Res. Nurs. 2018, 23, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, M.; Feldmann, M.; Vegetti, F. Work Values and the Value of Work: Different Implications for Young Adults’ Self-Employment in Europe. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2019, 682, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shir, N.; Nikolaev, B.N.; Wincent, J. Entrepreneurship and Well-Being: The Role of Psychological Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, A.; Maestripieri, L.; Armano, E. The Precariousness of Knowledge Workers: Hybridisation, Self-Employment and Subjectification. Work Organ. Labour Glob. 2016, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, B.; Chittenden, F. Fiscal Policy and Self-Employment: Targeting Business Growth. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapisz, A. Health Insurance Coverage and Sources of Advice in Entrepreneurship: Gender Differences. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, T. What’s in a Name? The Value of ‘Entrepreneurs’ Compared to ‘Self-Employed’... But What about ‘Freelancing’ or ‘IPro’? In The Handbook of Research on Freelancing and Self-Employment; Senate Hall Academic Publishing: Dublin, Ireland, 2015; pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Conen, W.; Schippers, J. Self-Employment: Between Freedom and Insecurity. In Self-Employment as Precarious Work: A European Perspective; Conen, W., Schippers, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, B.J.; Coutts, A.P. The Experience of Self-Employment Among Young People: An Exploratory Analysis of 28 Low- to Middle-Income Countries. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osnowitz, D. Freelancing Expertise: Contract Professionals in the New Economy; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, C.M.; Pifer, N.D.; Plunkett, E.P. Career Expectations and Optimistic Updating Biases in Minor League Baseball Players. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 129, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, J.; Deborah, D.M.; Eiffe, F.F.; Vanroelen, C. Does Employment Status Matter for Job Quality? A Cross-National Perspective. Work A J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2023, 75, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, J.; Moortel, D.D.; Wilkens, M.; Vanroelen, C. What’s up with the Self-Employed? A Cross-National Perspective on the Self-Employed’s Work-Related Mental Well-Being. SSM-Popul. Health 2018, 4, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.H.; MacEachen, E.; Hopwood, P.; Goyal, J. Self-Employment, Work and Health: A Critical Narrative Review. Work 2021, 70, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Mazzola, J.J. A Qualitative Study of Stress in Individuals Self-Employed in Solo Businesses. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. Motivation and Entrepreneurial Cognition. In Entrepreneurial Cognition; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 51–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M. Switching to Self-Employment Can Be Good for Your Health. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 664–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Wach, K.; Schaefer, R. Perceived Public Support and Entrepreneurship Attitudes: A Little Reciprocity Can Go a Long Way! J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyzo Vzw. Beleidsaanbevelingen van Dyzo Vzw. Available online: https://www.dyzo.be/ckfinder/userfiles/files/2020%2011%2026%20beleidsaanbevelingen%20Dyzo%20symposium.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Gignac, G.E. Modeling the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding: Evidence in Favor of a Revised Model of Socially Desirable Responding. J. Pers. Assess. 2013, 95, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, N.L. Examining Social Desirability Bias in Measures of Financial Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, USA, 2015; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.N.; Johnson, S.; Niven, K. “That’s Not What I Signed up for!” A Longitudinal Investigation of the Impact of Unmet Expectation and Age in the Relation between Career Plateau and Job Attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 107, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Guest, D.; Budjanovcanin, A. From Anchors to Orientations: Towards a Contemporary Theory of Career Preferences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Hart, M.; Mickiewicz, T.; Drews, C.-C. Understanding Motivations for Entrepreneurship; BIS Research Paper: Fremont, CA, USA, 2015; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Kalenkoski, C.M.; Pabilonia, S.W. Impacts of COVID-19 on the Self-Employed; GLO Discussion Paper, No. 843; Global Labour Organization (GLO): Essen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Exploring Self-Employment in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).