Mechanical, Durability, and Environmental Performance of Limestone Powder-Modified Ultra-High-Performance Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

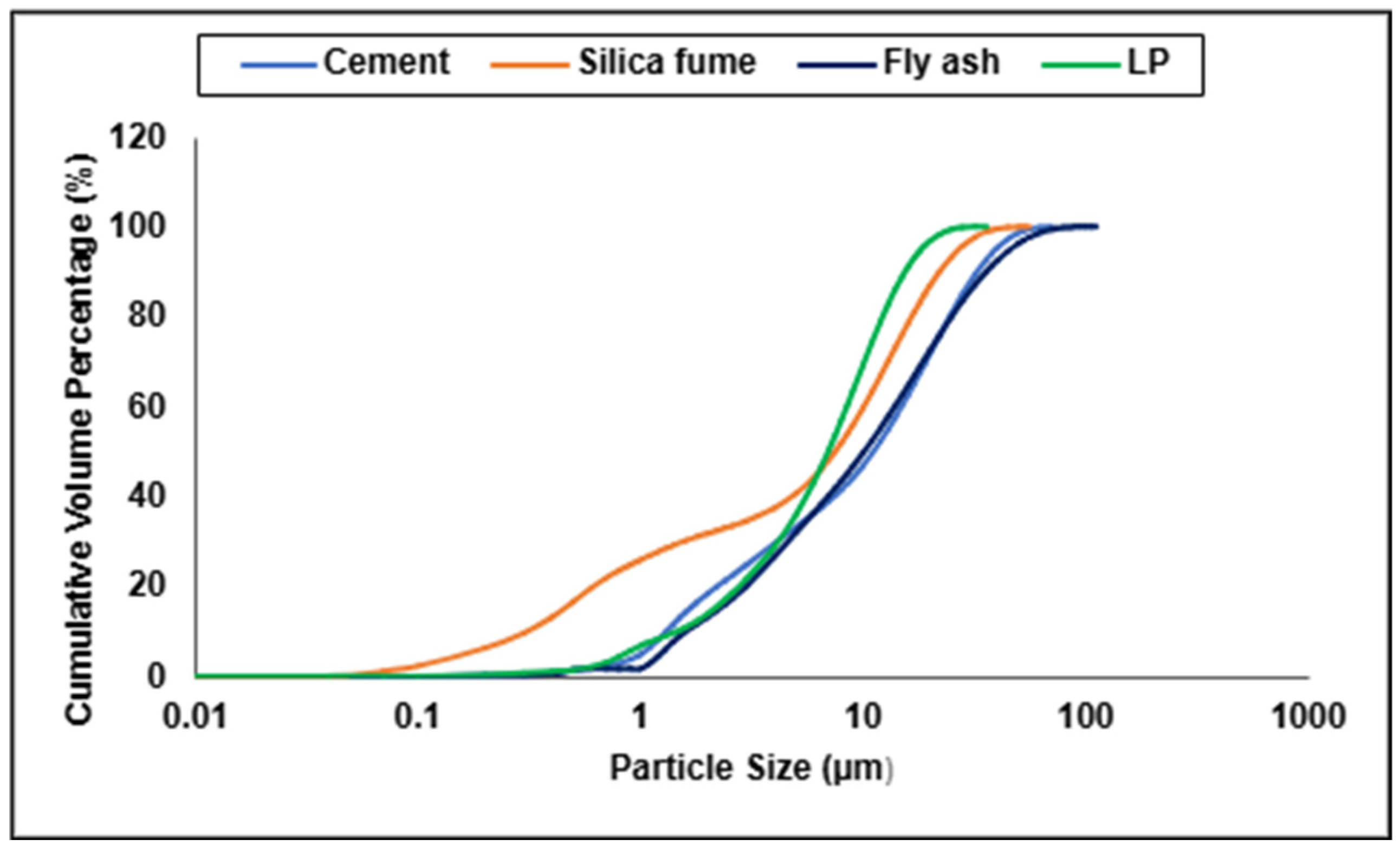

2.1. Materials

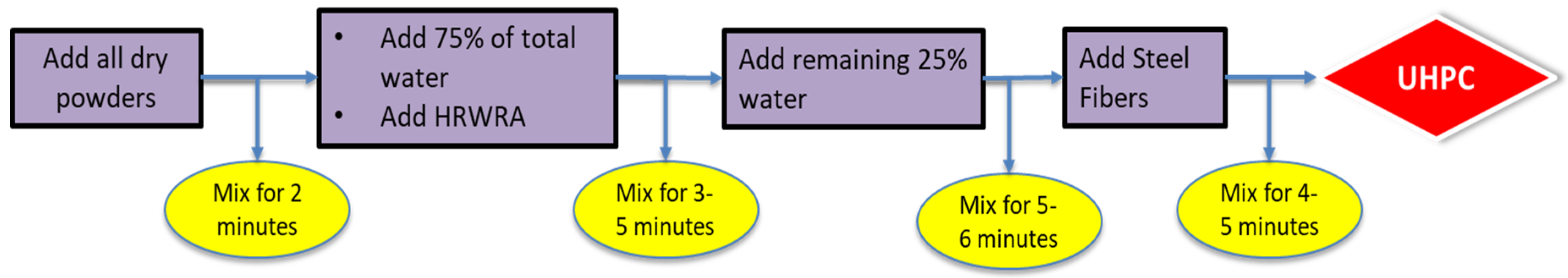

2.2. Mixture Proportioning, Specimen Preparation and Testing

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Workability

2.3.2. Compressive Strength

2.3.3. Split Tensile Strength

2.3.4. Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio

2.3.5. Flexural Strength

2.3.6. Direct Tension

2.3.7. Drying and Autogenous Shrinkage

2.3.8. Rapid Chloride Permeability Test (RCPT)

2.3.9. Surface Resistivity

2.3.10. Freezing and Thawing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Workability

3.2. Compressive Strength

3.3. Split Tensile Strength

3.4. Modulus of Elasticity (MOE)

3.5. Flexural Properties

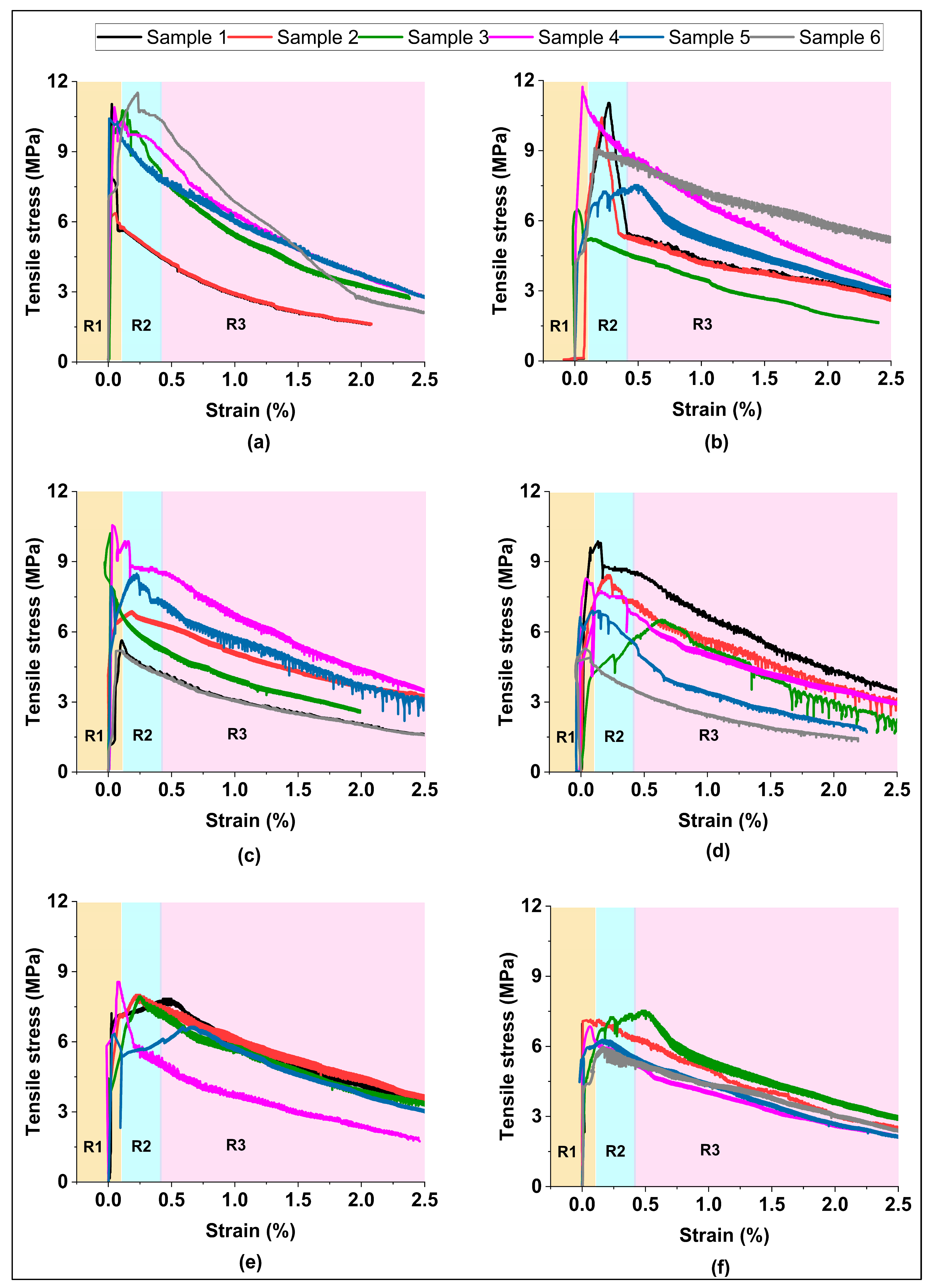

- Transition stage (I): Load-bearing capacity decreases as tensile stresses transfer from the concrete matrix to the steel fibers, initiating micro-cracks.

- Deflection hardening stage (II): Load continues to increase with deflection as fibers bridge cracks and hinder propagation.

- Post-peak stage (III): Significant ductility is observed, with load capacity gradually decreasing due to bond failure or fiber rupture.

3.5.1. Modulus of Rupture

3.5.2. Peak Flexural Strength

3.5.3. Residual Flexural Strength

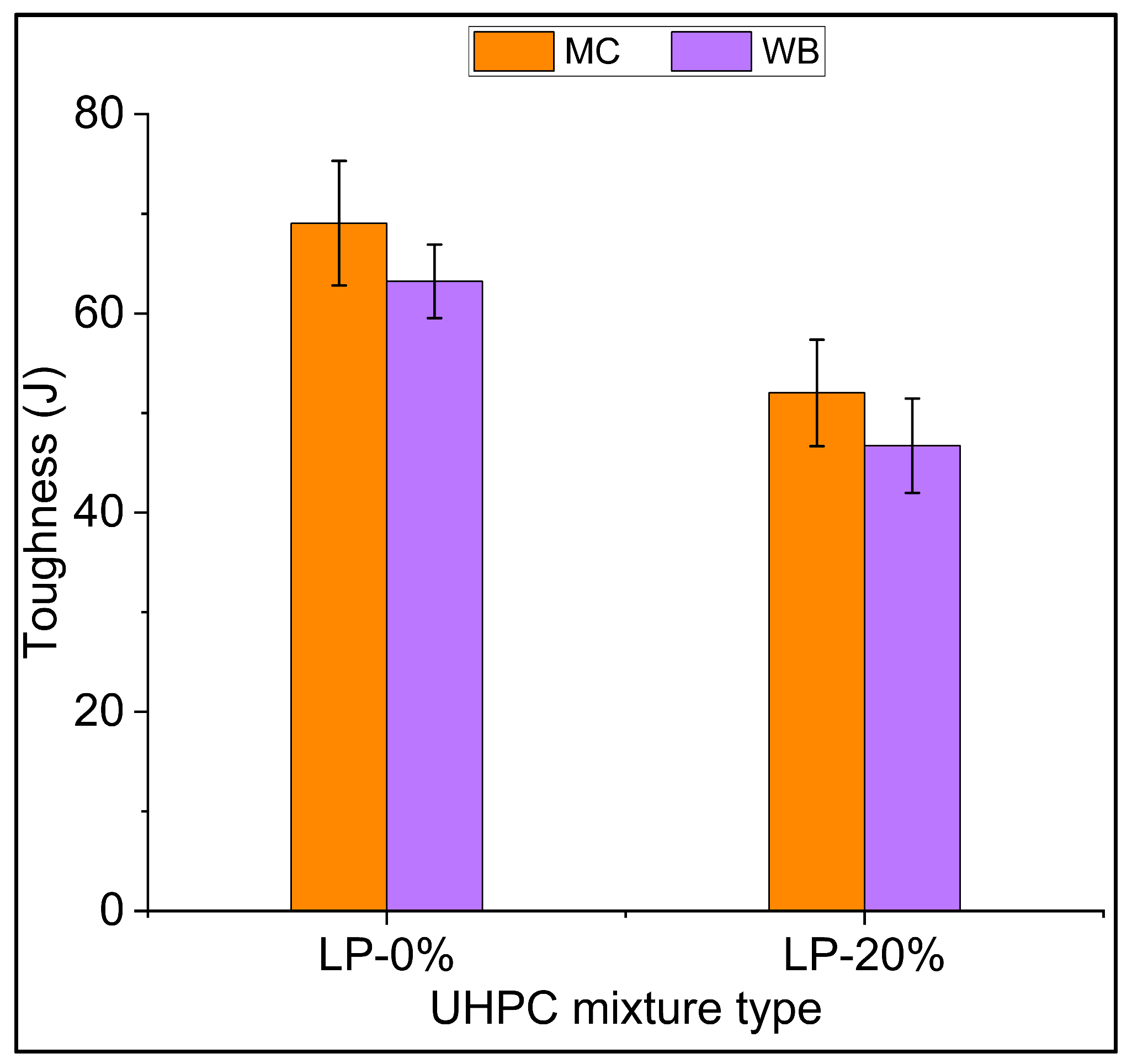

3.5.4. Toughness

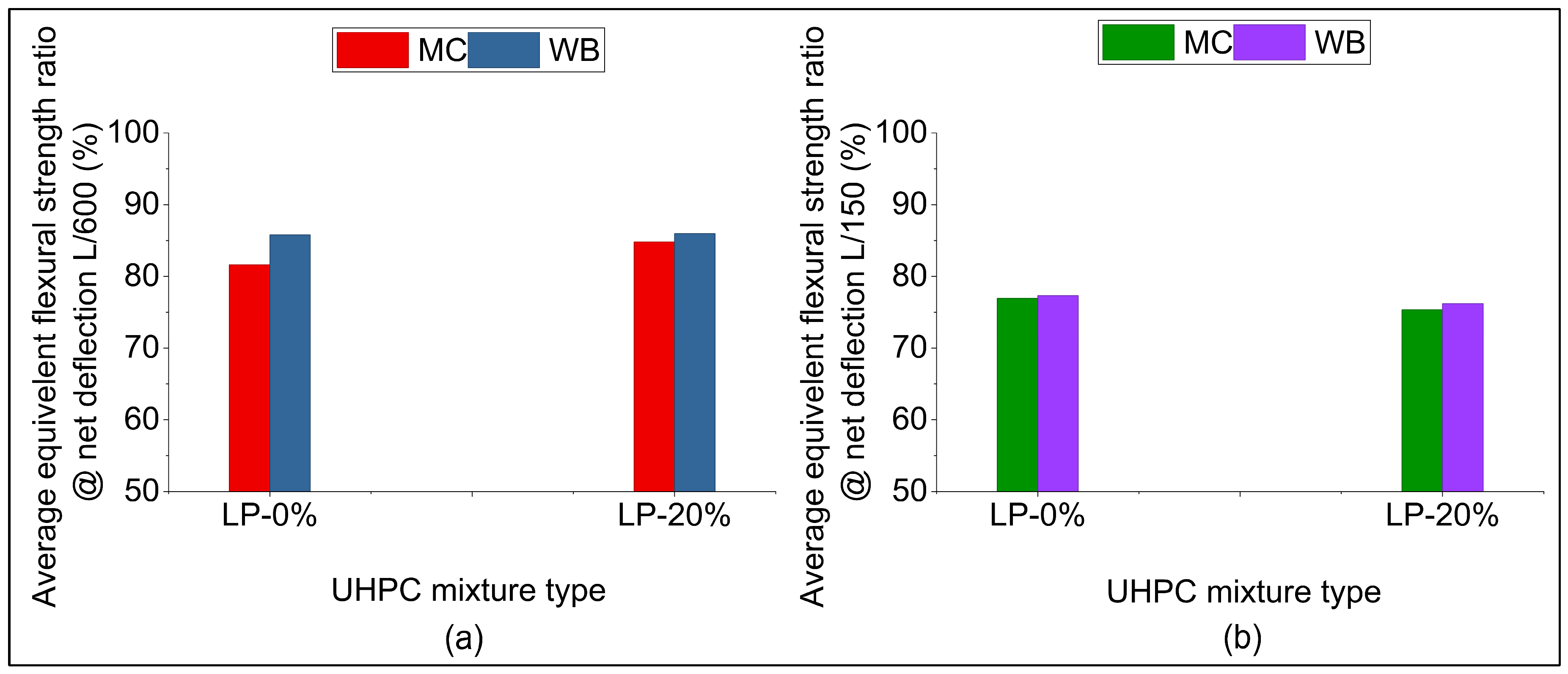

3.5.5. Equivalent Flexural Strength Ratio

3.6. Direct Tensile Strength

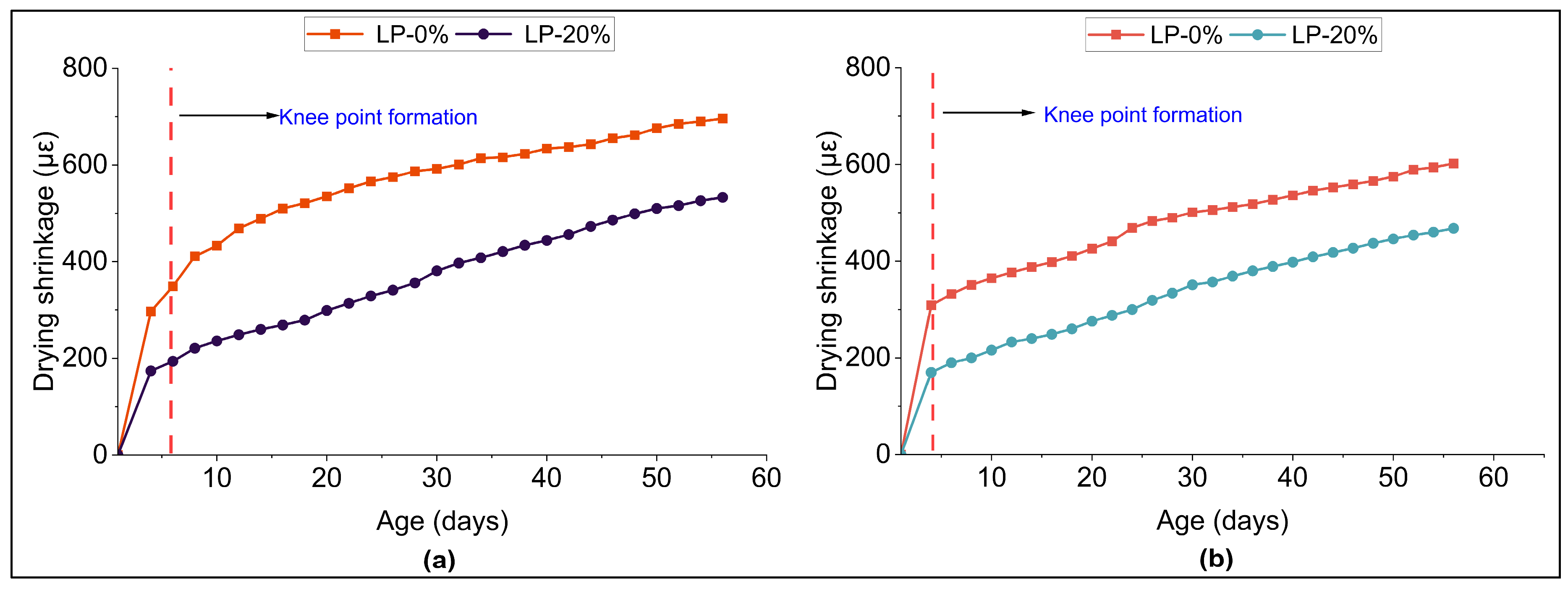

3.7. Shrinkage

3.7.1. Autogenous Shrinkage

3.7.2. Drying Shrinkage

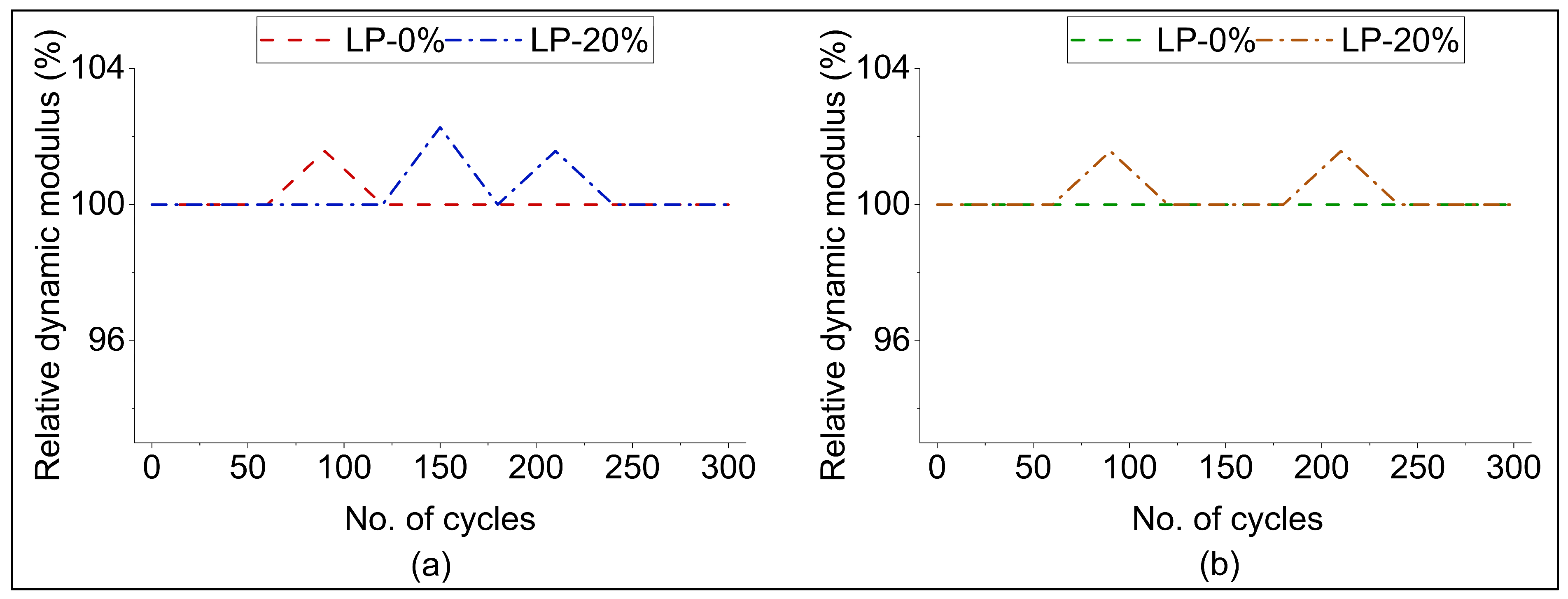

3.8. Resistance to Rapid Freezing and Thawing Cycles

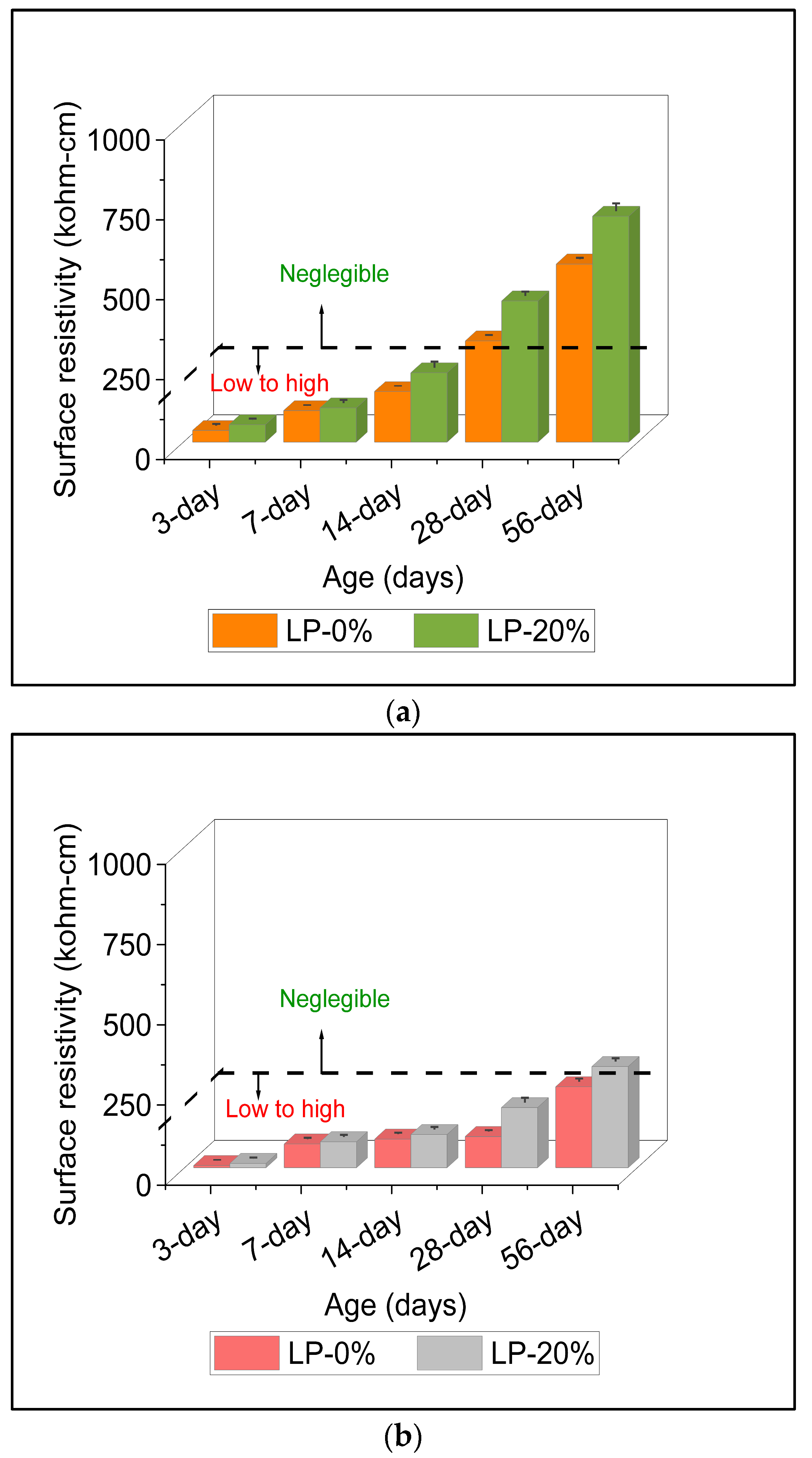

3.9. Surface Resistivity

3.10. Rapid Chloride Permeability Test

3.11. Microstructural Basis of Mechanical and Durability Behavior

4. Sustainability

Cost and CO2 Emissions Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richard, P.; Cheyrezy, M.H. Reactive Powder Concretes With High Ductility and 200-800 MPa Compressive Strength. In Proceedings of the V. Mohan Malhotra Symposium; Mehta, P.K., Ed.; ACI SP 144-24; Victoria Wieczorek: Detroit, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Dili, A.S.; Santhanam, M. Investigations on Reactive Powder Concrete: A Developing Ultra High Strength Technology. Indian Concr. J. 2004, 78, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Collepardi, S.; Coppola, L.; Troli, R.; Collepardi, M. Mechanical properties of modified reactive powder concrete. ACI Spec. Publ. 1997, 173, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, P.; Cheyrezy, M. Composition of reactive powder concretes. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P. Influence of fibre geometry and matrix maturity on the mechanical performance of ultra high-performance cement-based composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 246–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, T.; Gilbert, L.; Allena, S.; Owusu-Danquah, J.; Torres, A. Development of non-proprietary ultra-high performance concrete mixtures. Buildings 2022, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell, E.; Price, L.; Martin, N.; Hendriks, C.; Meida, L.O. Carbon dioxide emissions from the global cement industry. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2001, 26, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Spiesz, P.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Mix design and properties assessment of ultra-high performance fibre reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 56, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpa, A.; Kowald, T.; Trettin, R. Phase development in normal and ultra high performance cementitious systems by quantitative X-ray analysis and thermoanalytical methods. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, S.; Mo, L.; Deng, M. Effects of steel slag powder and expansive agent on the properties of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): Based on a case study. Materials 2020, 13, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Hakeem, I.; Maslehuddin, M. Development of UHPC Mixtures Utilizing Natural and Industrial Waste Materials as Partial Replacements of Silica Fume and Sand. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 713531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, A.; Middendorf, B. Influence of silica fume on properties of fresh and hardened ultra-high performance concrete based on alkali-activated slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 100, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Liu, Y.; Yan, P. Uncovering the effect of fly ash cenospheres on the macroscopic properties and microstructure of ultra high-performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286, 122977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, R.; Kadri, E.H. Influence of silica fume on the workability and the compressive strength of high-performance concretes. Cem. Concr. Res. 1998, 28, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, X. Study on self-desiccation effect of high performance concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2004, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.; Hansen, P.F. Autog enous deformation and change of the relative humidity in silica fume-modified cement paste. Mater. J. 1996, 93, 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.P.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Chen, W.; Yu, Q. Optimization and characterization of high-volume limestone powder in sustainable ultra-high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Pyo, S. The role of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in ultra high performance concrete (UHPC): A review. Materials 2021, 14, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeluri, M.; Ertugral, E.; Sharma, Y.; Fodor, P.; Kothapalli, C.; Allena, S. Revolutionizing ultra-high performance concrete: Unleashing metakaolin and diatomaceous earth as sustainable fly ash alternatives. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 460, 139822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, C.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, Z.; Jia, H.; Ou, Z. A review on use of limestone powder in cement-based materials: Mechanism, hydration and microstructures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kazemi-Kamyab, H.; Sun, W.; Scrivener, K. Effect of replacement of silica fume with calcined clay on the hydration and microstructural development of eco-UHPFRC. Mater. Des. 2017, 121, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, C.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, Z.; Jia, H. A review on effects of limestone powder on the properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 192, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P.; Ferraris, C.F.; Jones, S.Z.; Lootens, D.; Zunino, F. Limestone and silica powder replacements for cement: Early-age performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 78, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Q. Impact of micromechanics on dynamic compressive behavior of ultra-high performance concrete containing limestone powder. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 243, 110160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Cao, Y.Y.Y.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Chen, W.; Yu, Q.L. Development and properties evaluation of sustainable ultra-high performance pastes with quaternary blends. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavetti, V.; Donza, H.; Menéndez, G.; Cabrera, O.; Irassar, E.F. Limestone filler cement in low w/c concrete: A rational use of energy. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, R.; Shui, Z.; Gao, X.; Han, J.; Lin, G.; Qian, D.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. Environmental and economical friendly ultra-high performance-concrete incorporating appropriate quarry-stone powders. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Yu, R.; Geng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, F.; Shui, Z.; Gao, X.; He, Y.; Chen, L. Possibility and advantages of producing an ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) with ultra-low cement content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 122023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. Supplementary Cementing Materials in Concrete; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, R. Utilization of silica fume in concrete: Review of hardened properties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Qiang, Y.; Ahmad, J.; Vatin, N.I.; El-Shorbagy, M.A. Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC): A state-of-the-art review. Materials 2022, 15, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Yeluri, M.; Allena, S.; Owusu-Danquah, J. Incorporating Limestone Powder and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag in Ultra-high Performance Concrete to Enhance Sustainability. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2024, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1437-20; Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50-mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C496/C496M-17; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C469-02; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C1609/C1609M-19a; Standard Test Method for Flexural Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (Using Beam With Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Graybeal, B.; Baby, F.; Marchand, P.; Toutlemonde, F. Direct and flexural tension test methods for determination of the tensile stress-strain response of UHPFRC. In Proceedings of the Kassel International Conference, Hipermat, Kassel, Germany, 7–9 March 2012; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C157/C157M-17; Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hardened Hydraulic-Cement Mortar and Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1202-19; Standard Test Method for Electrical Indication of Concrete’s Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA. USA, 2019.

- AASHTO TP95-11; Standard Method of Test for Surface Resistivity Indication of Concrete’s Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- ASTM C666/C666M-15; Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Kang, S.T.; Kim, J.K. Investigation on the flexural behavior of UHPCC considering the effect of fiber orientation distribution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.T.; Lee, B.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y.Y. The effect of fibre distribution characteristics on the flexural strength of steel fibre-reinforced ultra high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2450–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Khayat, K.H.; Shi, C. Changes in rheology and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete with silica fume content. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 123, 105786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, K.; El-Tawil, S.; Naaman, A.E. Properties of strain hardening ultra high performance fiber reinforced concrete (UHP-FRC) under direct tensile loading. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 48, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Khayat, K.H. Mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete enhanced with graphite nanoplatelets and carbon nanofibers. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2016, 107, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sersale, R. Advances in Portland and blended cements. In Proceedings of the 9 th International Congress on the Chemistry of Cement, New Delhi, India, 23–28 November 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, M.; Lawrence, P.; Ringot, E. Efficiency of mineral admixtures in mortars: Quantification of the physical and chemical effects of fine admixtures in relation with compressive strength. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Zhou, X.; Ji, L.; Dai, W.; Lu, L.; Cheng, X. Effects of limestone powders on pore structure and physiological characteristics of planting concrete with sulfoaluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Tang, X.; Bai, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, L. Effect of Curing Temperature on Mechanical Strength and Thermal Properties of Hydraulic Limestone Powder Concrete. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 33, 11214–11230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1856; Standard Practice for Fabricating and Testing Specimens of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Shi, X.S.; Collins, F.G.; Zhao, X.L.; Wang, Q.Y. Mechanical properties and microstructure analysis of fly ash geopolymeric recycled concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 237, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakır, Ö. Experimental analysis of properties of recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) concrete with mineral additives. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.; Zobel, M.; Buenfeld, N.R.; Zimmerman, R.W. Influence of the interfacial transition zone and microcracking on the diffusivity, permeability and sorptivity of cement-based materials after drying. Mag. Concr. Res. 2009, 61, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, S.; Turk, K.; Ulugerger, K. Fresh and hardened properties of self consolidating Portland limestone cement mortars: Effect of high volume limestone powder replaced by cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 196, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, C.; Gao, Z.; Wang, F. A review on fracture properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zou, F.; He, M.; Mao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, Z. A comparative study of temperature of mass concrete placed in August and November based on on-site measurement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutanji, H.A.; Bayasi, Z. Effect of curing procedures on properties of silica fume concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.A.; Yuan, Q.; Photwichai, N. Use of materials to lower the cost of ultra-high-performance concrete–A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 127045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarzewski, P. Study of toughness and macro/micro-crack development of fibre-reinforced ultra-high performance concrete after exposure to elevated temperature. Materials 2019, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, H.G.; Graybeal, B.A. Ultra-High Performance Concrete: A state-of-the-Art Report for the Bridge Community (No. FHWA-HRT-13-060); United States. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration; Office of Infrastructure Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Nayar, S.K.; Gettu, R.; Krishnan, S. Characterisation of the toughness of fibre reinforced concrete–revisited in the Indian context. Indian Concr. J. 2014, 88, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rashiddadash, P.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Mahdikhani, M. Experimental investigation on flexural toughness of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete (HFRC) containing metakaolin and pumice. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 51, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ding, W.; Qiao, Y. Experimental investigation on the flexural behavior of hybrid steel-PVA fiber reinforced concrete containing fly ash and slag powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 288, 116706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P. Concrete: Structure, Properties and Materials, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: NewYork, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Lu, L.; He, Y.; Wang, F.; Hu, S. The effect of curing regimes on the mechanical properties, nano-mechanical properties and microstructure of ultra-high performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 118, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irassar, E.F. Sulfate attack on cementitious materials containing limestone filler—A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A.; Graybeal, B.; Haber, Z. Time-dependent properties of ultrahigh-performance concrete: Compressive creep and shrinkage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, N.V.; Ye, G.; van Breugel, K. Mitigation of early age shrinkage of ultra high performance concrete by using rice husk ash. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on UHPC and Nanotechnology for High Performance Construction Materials: Ultra-High Performance Concrete and Nanotechnology in Construction (HIPERMAT-2012), Kassel, Germany, 7–9 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; Khayat, K.H.; Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; Khayat, K.H. Investigation of mechanical properties and shrinkage of ultra-high performance concrete: Influence of steel fiber content and shape. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 174, 107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Xia, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Jia, X. Effect of concrete composition on drying shrinkage behavior of ultra-high performance concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 62, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Shen, D.; Khan, K.A.; Jan, A.; Khubaib, M.; Ahmad, T.; Nasir, H. Effectiveness of limestone powder in controlling the shrinkage behavior of cement based system: A review. Silicon 2009, 31, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro-Villanueva, J.; Newtson, C.M.; Weldon, B.D.; Jauregui, D.V.; Allena, S. Freezing and thawing durability of ultra high strength concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Arch. 2013, 7, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bahmani, H.; Mostofinejad, D. Microstructure of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC)–a review study. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; He, Y.; Lü, L.; Zhang, X. Effect of High Content Limestone Powder on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Cement-based Materials. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, C. owards greener ultra-high performance concrete based on highly-efficient utilization of calcined clay and limestone powder. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carrillo, G.; Durán-Herrera, A.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Effect of limestone and quartz fillers in UHPC with calcined clay. Materials 2022, 15, 7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Yang, Q.; Lin, X.; Gao, X.; Cheng, H.; Huang, Y.; Du, P.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. The synergistic effects of ultrafine slag powder and limestone on the rheology behavior, microstructure, and fractal features of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Materials 2023, 16, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, K.; Boisvert-Cotulio, C. Material efficiency in the design of ultra-high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 86, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalman, A.; Dang, C.N.; Martí-Vargas, J.R.; Hale, W.M. Mixture-proportioning of economical UHPC mixtures. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 27, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, S.; Majsztrik, P.; Rojas, I.S.; Gavvalapalli, M. Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Low-Carbon Cement; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Flower, D.J.; Sanjayan, J. Green house gas emissions due to concrete manufacture. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2007, 12, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D. The effect of silica fume on the properties of concrete as defined in concrete society report 74, cementitious materials. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Our World in Concrete and Structures, Singapore, 27–28 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipour, S.; Nikbin, I.M.; Dezhampanah, S.; Mohebbi, R.; Moghadam, H.; Charkhtab, S.; Moradi, A. Mechanical properties, durability and environmental evaluation of rubberized concrete incorporating steel fiber and metakaolin at elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kazemi-Kamyab, H.; Sun, W.; Scrivener, K. Effect of cement substitution by limestone on the hydration and microstructural development of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 77, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesoğlu, M.; Güneyisi, E.; Kocabağ, M.E.; Bayram, V.; Mermerdaş, K. Fresh and hardened characteristics of self compacting concretes made with combined use of marble powder, limestone filler, and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.G.; Kwan, A.K. Adding limestone fines as cementitious paste replacement to improve tensile strength, stiffness and durability of concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 60, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, K.; Kjellsen, K.O.; Sellevold, E.; Justnes, H. Synergy between fly ash and limestone powder in ternary cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.; Siddique, R. Recent advances in understanding the role of supplementary cementitious materials in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Compounds (%) | Cement | Silica Fume | Fly Ash | LP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 20.2 | 18.9 | 38.03 | 1 |

| Al2O3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 18.44 | 0.15 |

| Fe2O3 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 5.16 | 0.15 |

| CaO | 63.8 | 63.1 | 16.05 | - |

| MgO | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.73 | - |

| SO3 | 0.35 | 3 | 3.3 | - |

| Na2O | - | 0.34 | 9.2 | - |

| K2O | - | - | 0.96 | - |

| MgCO3 | - | - | - | 44.3 |

| CaCO3 | - | 91 | - | 54.2 |

| CaSO4 2H2O | - | |||

| Mn | - | |||

| S | - | - | - | - |

| Loss on ignition | 0.88 | 5.4 | 2.1 | - |

| Insoluble residue | 0.34 | - | - | - |

| Relative density | 3.15 | 3.15 | 2.58 | 1.28 |

| moisture content (%) | - | - | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Blaine fineness (m2/kg) | 401 | - | - | - |

| Type | Designation | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Moist curing | MC | The specimens were left in the mold for a period of 24 h. Following demolding, they were subsequently relocated to a curing room with controlled temperature and humidity conditions until testing. |

| Warm bath curing | WB | The specimens were left in the molds for a period of 24 h. Following the demolding, the specimens were then subjected to curing in a water bath maintained at 90 °C until testing. |

| Mixture Designation | Cement | SF | FA | LP | Sand | Steel Fibers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | |

| UHPC mixtures without LP | 890 | 68 | 101 | 0 | 1110 | 0 |

| 890 | 68 | 101 | 0 | 1070 | 119 | |

| UHPC mixtures with 20% LP | 712 | 68 | 101 | 178 | 893 | 0 |

| 712 | 68 | 101 | 178 | 853 | 119 |

| Materials Used | Cost $US/ton | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cement | 82–110 | [80,81] |

| Silica fume | 350–1100 | [80,81] |

| Fly ash | 46–60 | [80] |

| LP | 122–124 | [80] |

| HRWRA | 3400 | [81] |

| Steel fibers | 5000 | [81] |

| Natural river sand | 100 | [60] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, Y.; Yeluri, M.; Allena, S. Mechanical, Durability, and Environmental Performance of Limestone Powder-Modified Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5040090

Sharma Y, Yeluri M, Allena S. Mechanical, Durability, and Environmental Performance of Limestone Powder-Modified Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Construction Materials. 2025; 5(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Yashovardhan, Meghana Yeluri, and Srinivas Allena. 2025. "Mechanical, Durability, and Environmental Performance of Limestone Powder-Modified Ultra-High-Performance Concrete" Construction Materials 5, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5040090

APA StyleSharma, Y., Yeluri, M., & Allena, S. (2025). Mechanical, Durability, and Environmental Performance of Limestone Powder-Modified Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Construction Materials, 5(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5040090