Shear Mechanism Differentiation Investigation of Rock Joints with Varying Lithologies Using 3D-Printed Barton Profiles and Numerical Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

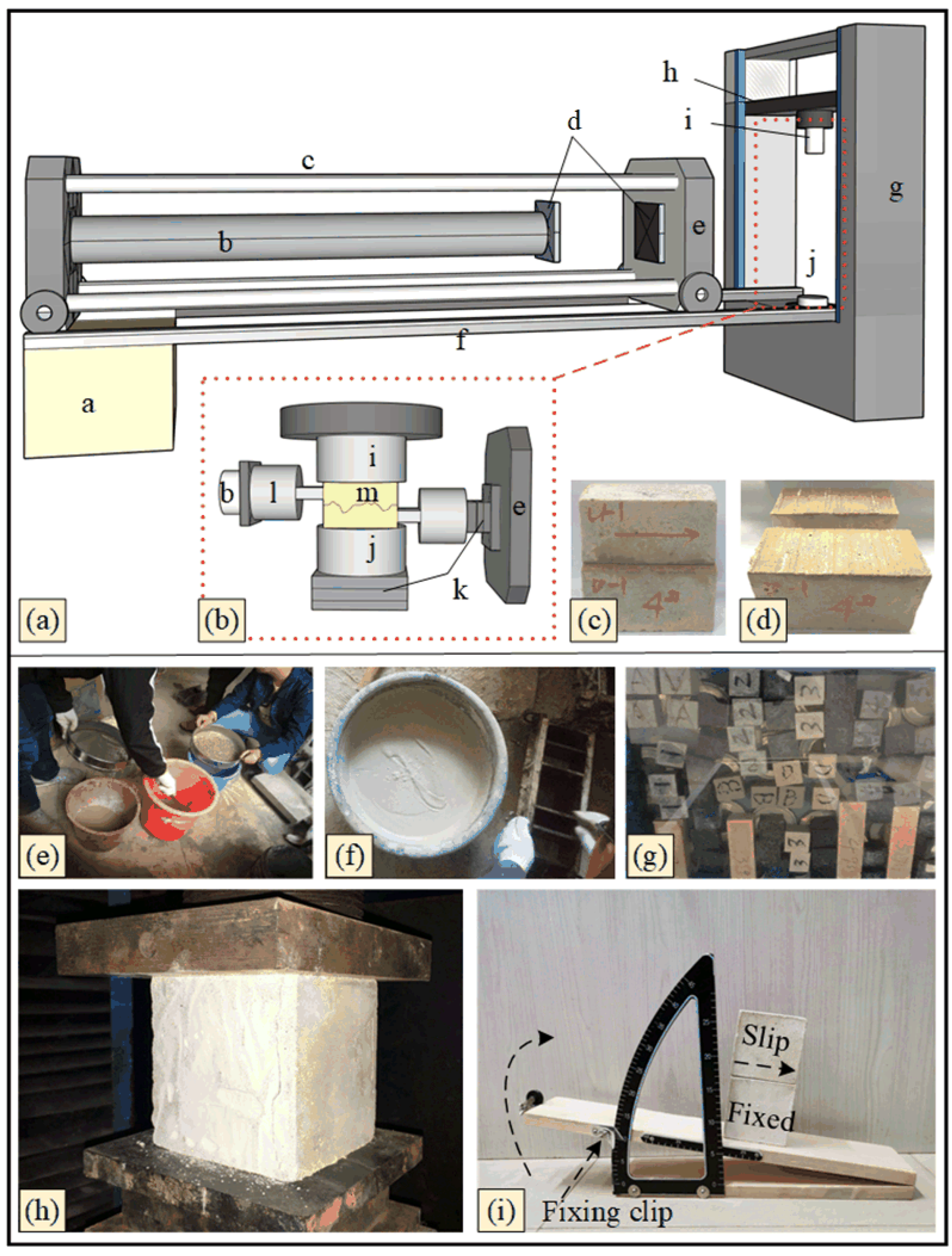

2. Molding and Experiment

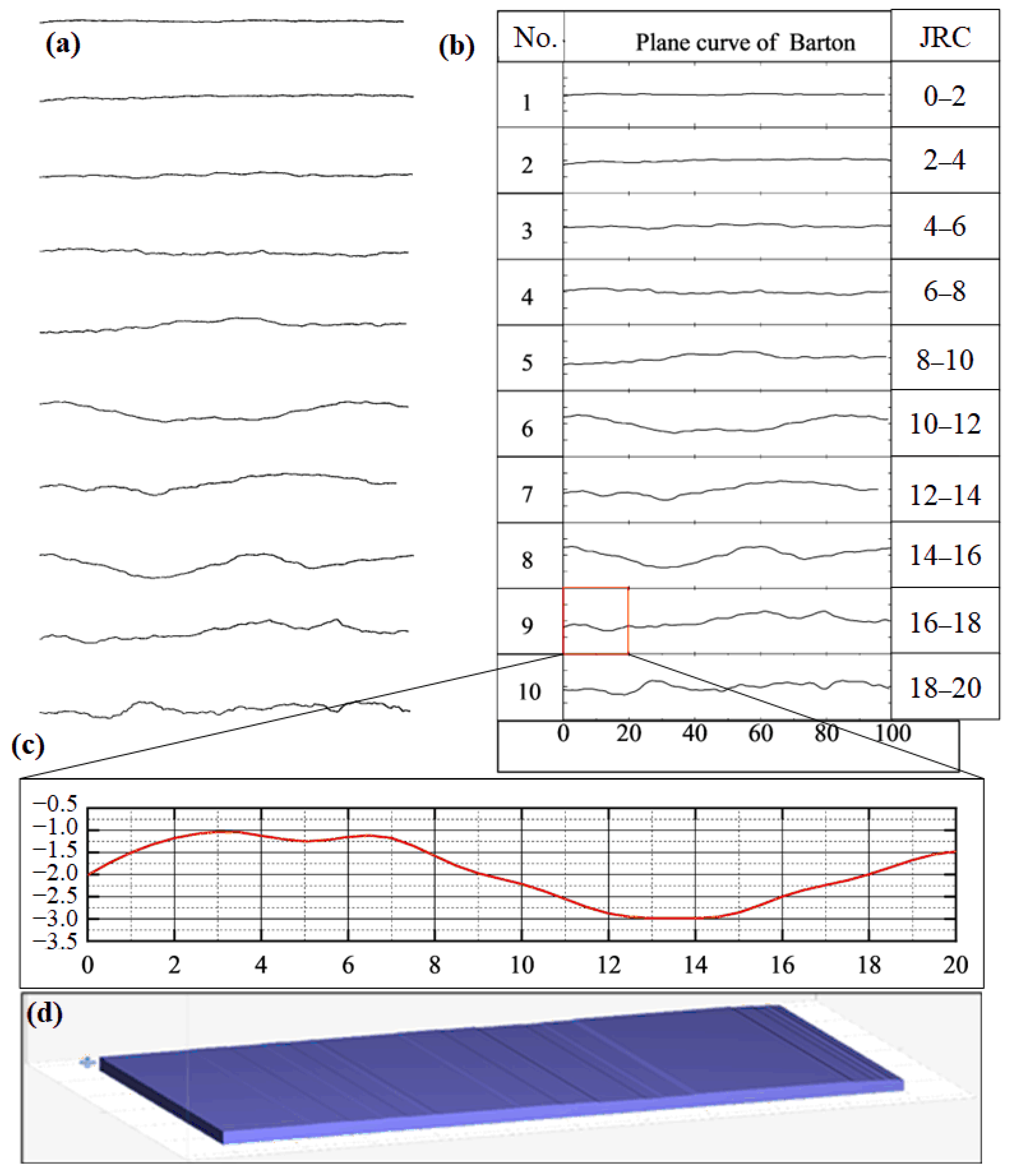

2.1. 3D-Printed Pattern

2.1.1. Printing Model Generation

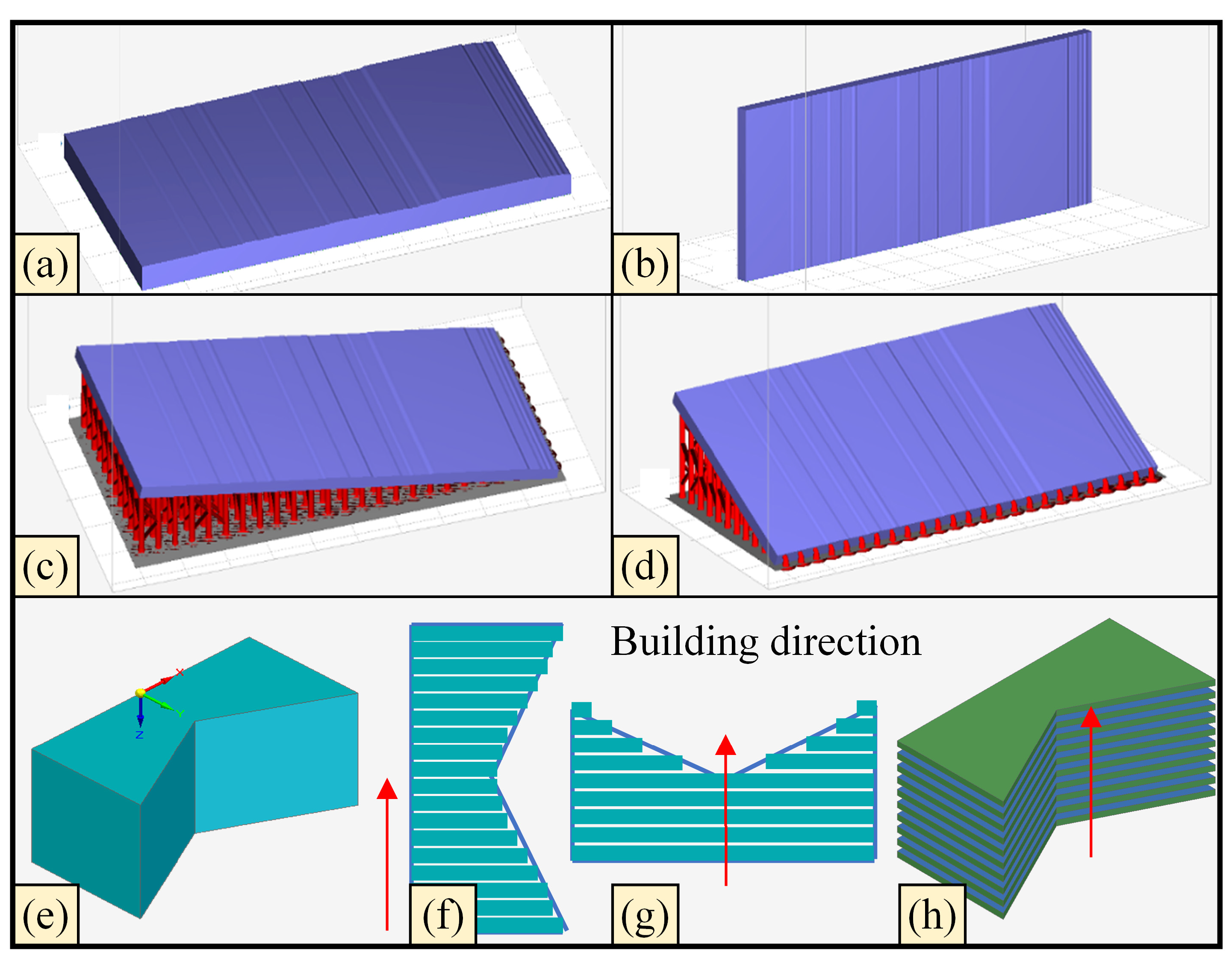

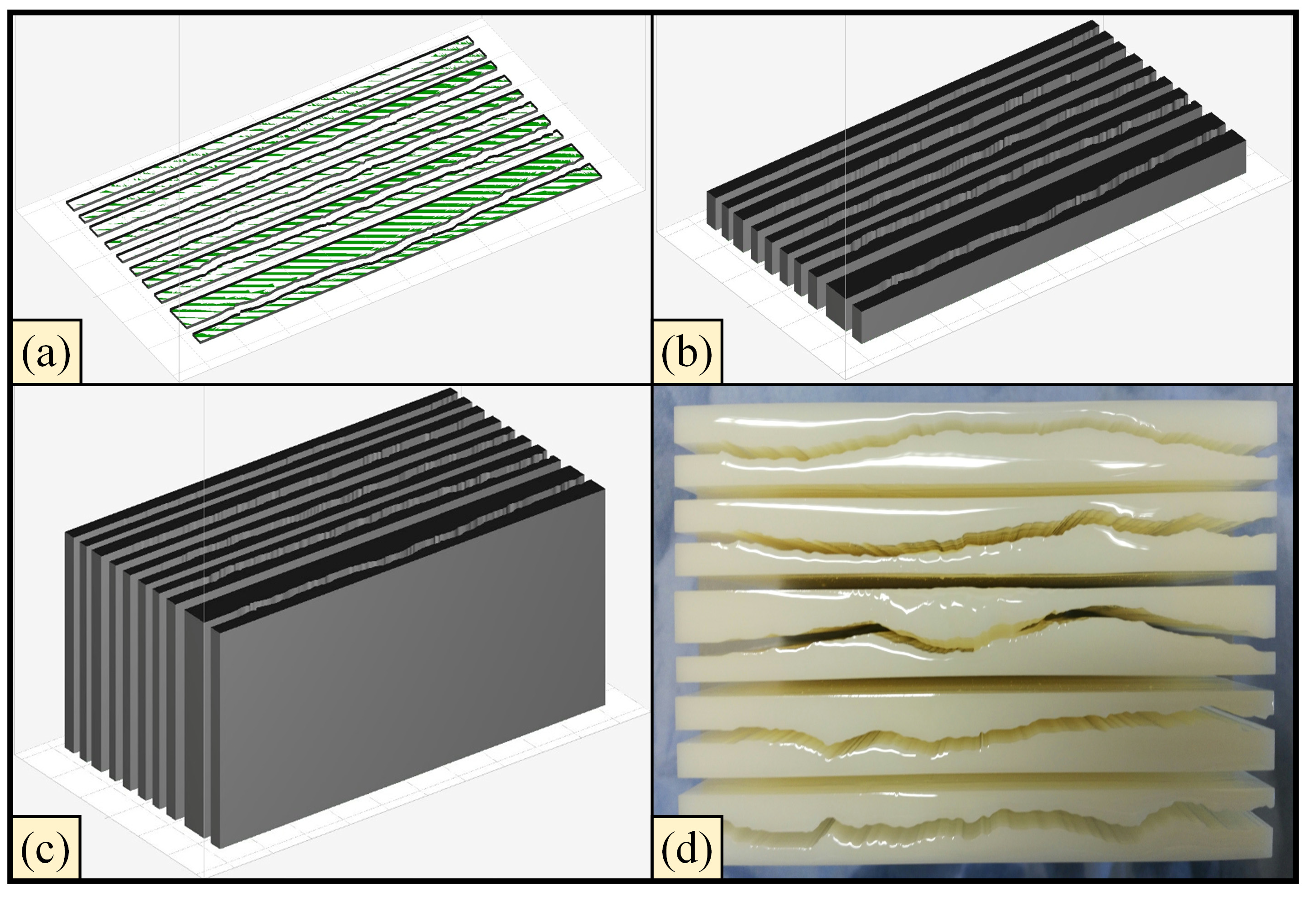

2.1.2. Printing Process and Parameters

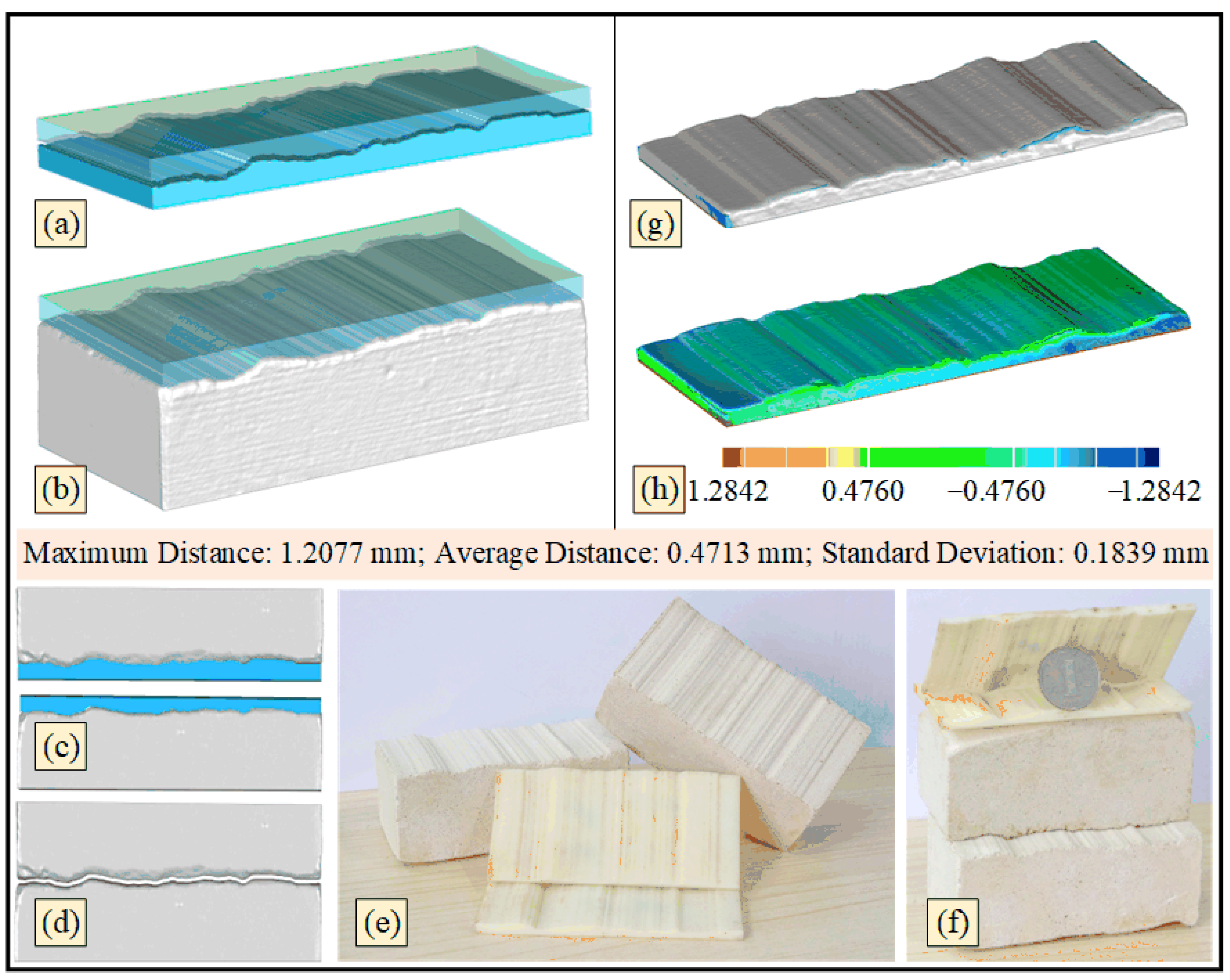

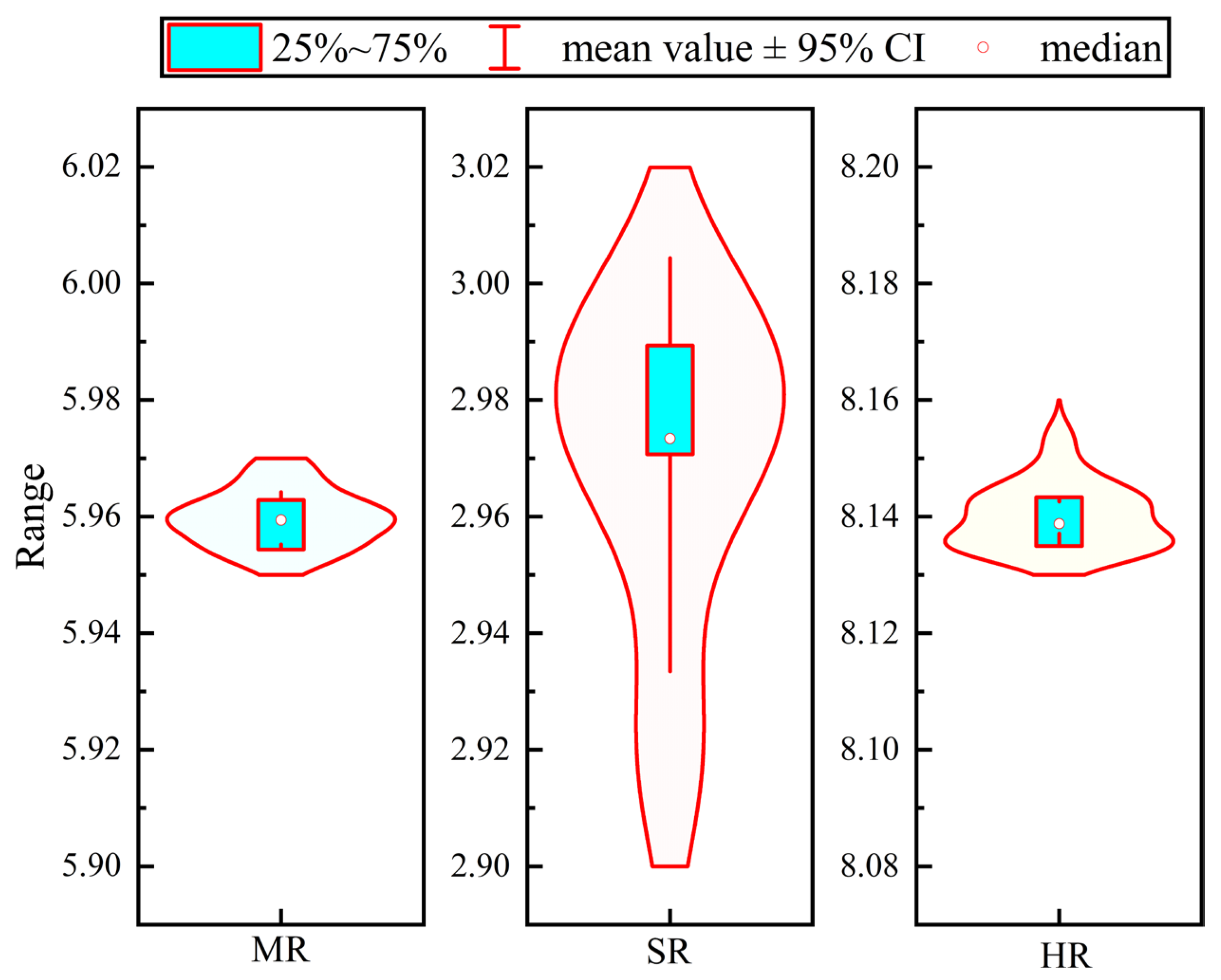

2.1.3. Print Accuracy Evaluation

2.2. Experiment

2.2.1. Molding Process

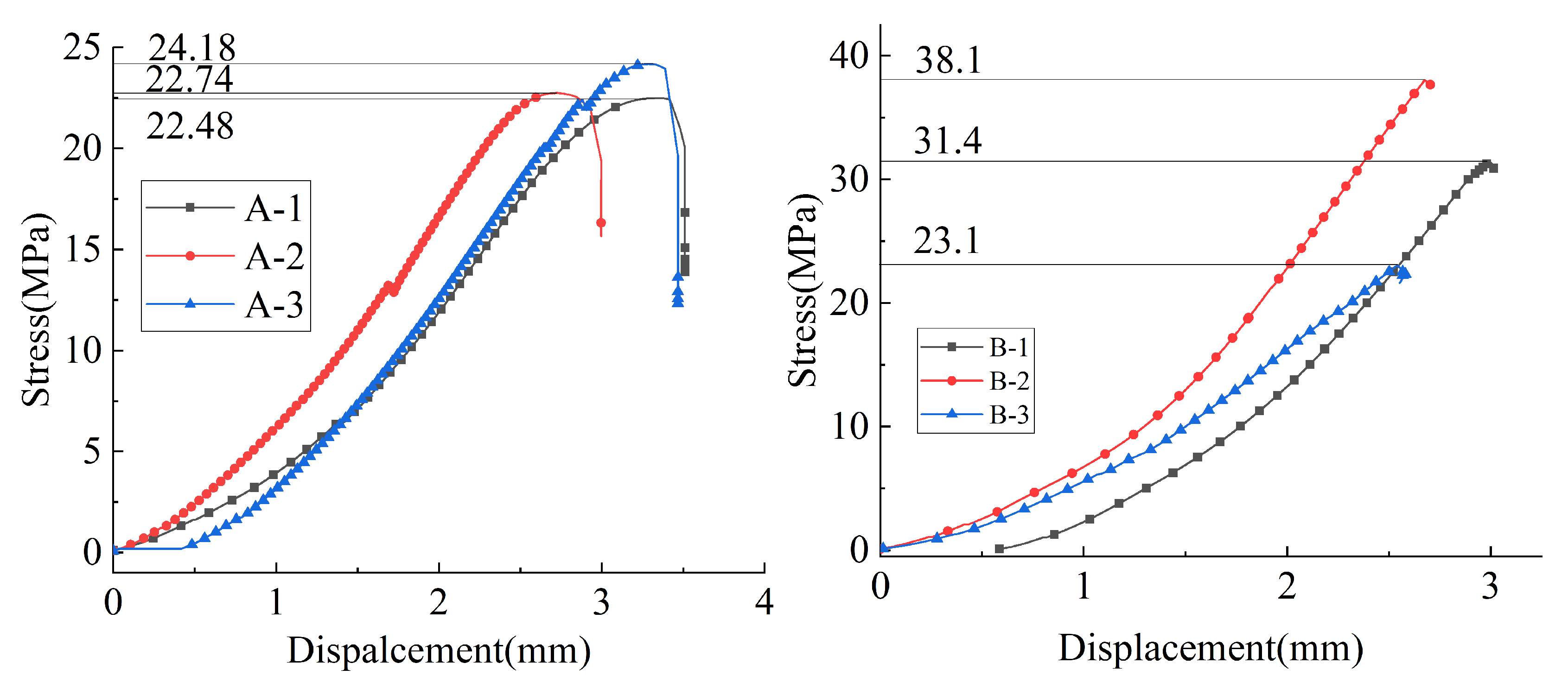

2.2.2. Determination of the Wall Rock Strength

2.2.3. Determination of the Basic Friction Angle

2.2.4. Joint Surfaces Shear Test

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Test Results and Analysis of the Wall Rock Strength and Basic Friction Angle

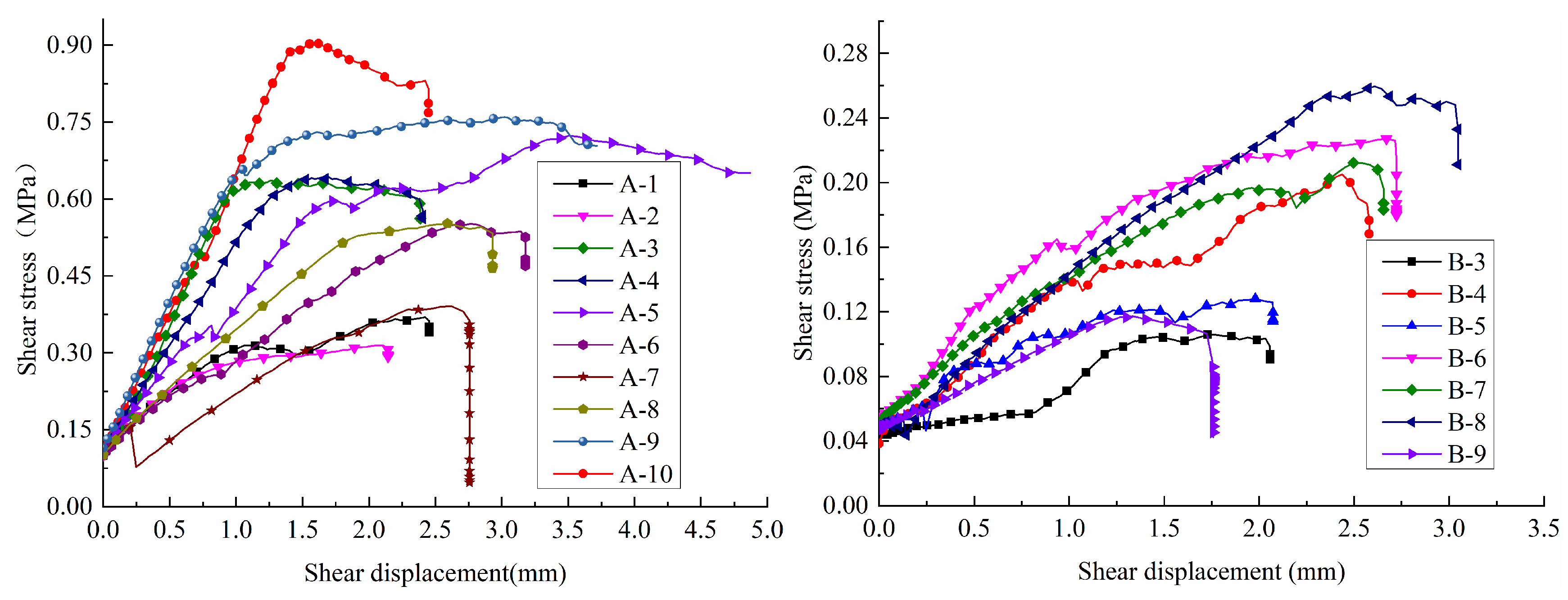

3.2. Shear Test Results and Analysis

3.2.1. Shear Displacement and Shear Stress

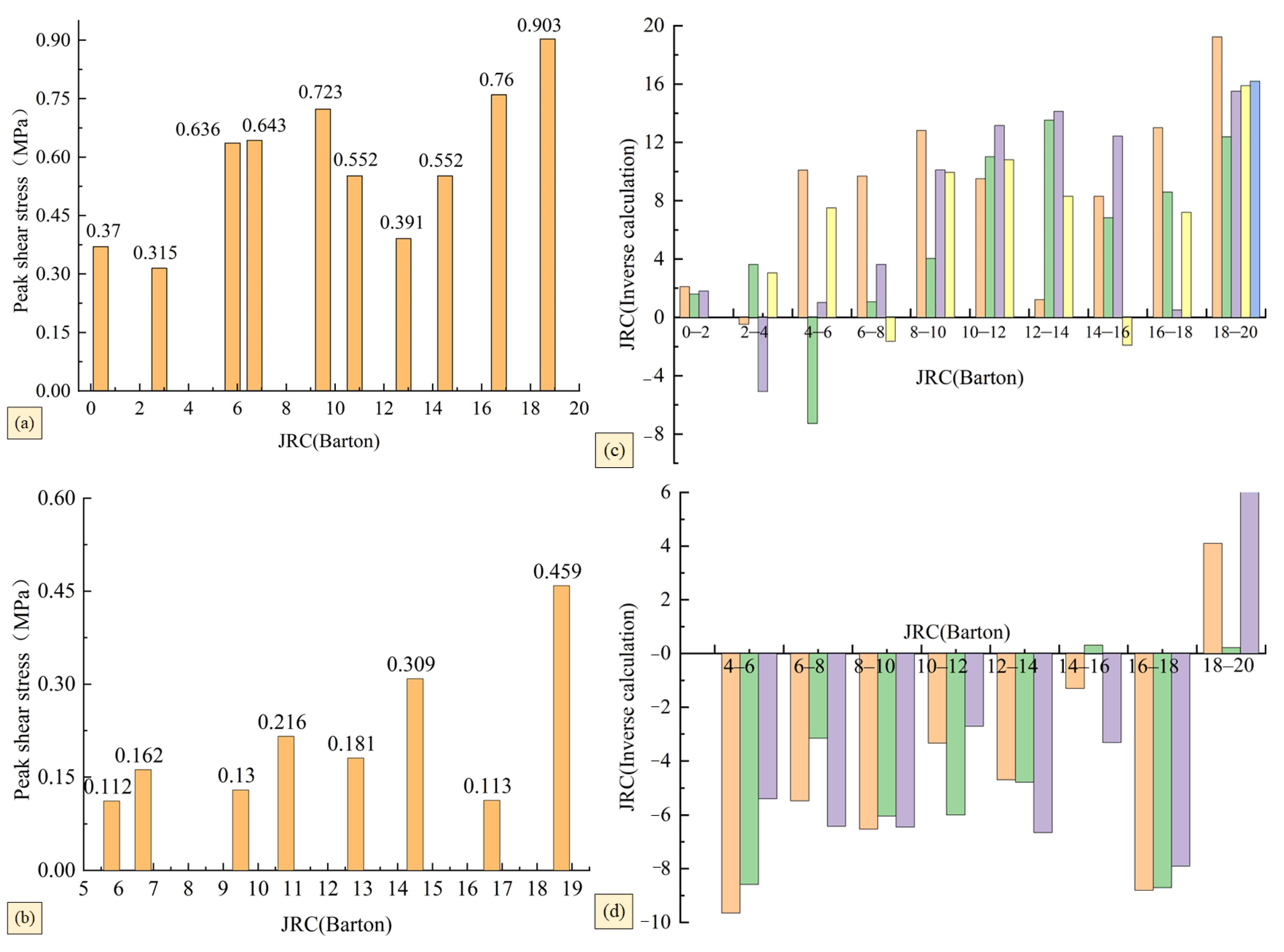

3.2.2. Peak Shear Stress and Inverse Calculation

4. Shear Failure Mode Analysis of Joint Surface Details

5. Analysis of Shear Mechanical Behavior of Joint Surface in Rock Masses with Different Hardness Levels

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The innovative application of high-precision 3D printing allows for accurate reproduction of standard roughness profiles, significantly reducing model variability in physical shear tests. This ensures reliable insights into the role of joint geometry in shear behavior.

- (2)

- The peak shear strength of joint surfaces increases with JRC, but the failure mechanisms differ by lithology: soft rocks rely more on interfacial friction, whereas in harder rocks, bulge shearing dominates. Thus, the influence of material strength must be considered alongside geometric parameters like JRC.

- (3)

- Shear curves exhibit lithology-dependent characteristics: harder rocks show higher peak and residual strengths and more pronounced stress fluctuations during loading, while softer rocks display smoother transitions and less prominent peak intervals. However, it is important to note that specific material properties, such as the effective joint wall compressive strength (JCS) and asperity degradation resistance, can lead to exceptions. As discussed and exemplified by Material A in Figure 7, a material with lower bulk uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) can still exhibit higher peak shear strength under certain conditions due to superior asperity interlocking and resistance to degradation at the joint surface.

- (4)

- Despite lithological differences, the residual shear behavior of joint surfaces tends to follow a similar trend across materials, suggesting that the post-peak phase may be governed by universal mechanical processes related to surface degradation and friction mobilization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grasselli, G.; Egger, P. Constitutive law for the shear strength of rock joints based on three-dimensional surface parameters. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2003, 40, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladanyi, B.; Archambault, G. Simulation of Shear Behavior of a Jointed Rock Mass. In Proceedings of the 11th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), Berkeley, CA, USA, 16 June 1969; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, N.; Wei, W.; Feng, X. Laboratory Investigation on Shear Behavior of Rock Joints and a New Peak Shear Strength Criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 3495–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, F.D. Multiple modes of shear failure in rock. In Proceedings of the 1st ISRM Congress, Lisbon, Portugal, 25–29 September 1966; pp. 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, N.; Bandis, S. Review of predictive capabilities of JRC-JCS model in engineering practice: Barton, N; Bandis, S Proc International Symposium on Rock Joints, Loen, 4–6 June 1990P603–610. Publ Rotterdam: A A Balkema, 1990. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1991, 28, A209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.; Bandis, S.; Bakhtar, K. Strength, deformation and conductivity coupling of rock joints. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1985, 22, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.C.; Jiao, Y.Y.; Wong, L.N.Y. Theoretical model with multi-asperity interaction for the closure behavior of rock joint. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 97, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Chiang, D.Y. An experimental study on the progressive shear behavior of rock joints with tooth-shaped asperities. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2000, 37, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.S.; Rasouli, V.; Barla, G. A laboratory shear cell used for simulation of shear strength and asperity degradation of rough rock fractures. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 46, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.-C.; Liu, Q.-S.; Liu, X.-Y. Shear behavior of rock joints and comparative study on shear strength criteria with three-dimensional morphology parameters. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 36, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.; Choubey, V. Shear Strength of Rock Joints in Theory and Practice. Rock Mech. 1977, 10, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, D.; Vanorio, T. Effects of changes in rock microstructures on permeability: 3-D printing investigation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 7494–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Gratchev, I.; Hein, M.; Balasubramaniam, A. The Application of Normal Stress Reduction Function in Tilt Tests for Different Block Shapes. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 3041–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Huang, M.; Luo, Z.; Jia, R. Similar material study of mechanical prototype test of rock structural plane. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.Q.; Jiang, Q.; Gong, Y.H.; Song, L.B.; Cui, J. A method for preparing natural joints of rock mass based on 3D scanning and printing techniques and its experimental validation. Yantu Lixue/Rock Soil Mech. 2015, 36, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, Z.; Ren, F.; Zhang, L.; Cai, M. Research on direct shear behaviour and fracture patterns of 3D-printed complex jointed rock models. Rock Soil Mech. 2020, 41, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, O.; Jeffery, M.; Moscato, P.; Grebogi, R.B.; Haque, M.N. Mathematical Modelling of Peak and Residual Shear Strength of Rough Rock Discontinuities Using Continued Fractions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Song, Z.; Zou, L.; Li, B. A Shear Behavior Prediction Model for Fresh Sedimentary Rock Fractures Considering Relation Between Shear Energy and Asperity Damage. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 7287–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, Y. Updates to JRC-JCS model for estimating the peak shear strength of rock joints based on quantified surface description. Eng. Geol. 2017, 228, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.K.; Basu, A. A modified JRC-JCS model and its applicability to weathered joints of granite and quartzite. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 6089–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Kim, K.Y.; Yeom, S.; Zhuang, L.; Park, S.; Min, K.-B. Surface roughness characterization of open and closed rock joints in deep cores using X-ray computed tomography. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 98, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hou, W.; Su, A. Shear characteristics and shear strength model of rock mass structural planes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solak, K.C.; Tuncay, E. An evaluation on Barton-Bandis shear strength criterion for discontinuities in weak materials under low normal stresses. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Zuo, S.; Li, D. Quantitative characterization of joint roughness based on semivariogram parameters. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 109, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, F.; Wolfs, R.; Ahmed, Z.; Salet, T. Additive manufacturing of concrete in construction: Potentials and challenges of 3D concrete printing. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2016, 11, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Luo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Li, D.; Zuo, S. A practical photogrammetric workflow in the field for the construction of a 3D rock joint surface database. Eng. Geol. 2020, 279, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Xie, W.; Jing, S.; Wang, X.; Su, Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the Mechanical Behavior of Rock-Like Material with Complex Discrete Joints. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 4493–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueng, T.S.; Jou, Y.J.; Peng, I.H. Scale effect on shear strength of computer-aided-manufactured joints. J. GeoEng. 2010, 5, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Yuan, W.; Wang, W.; Sun, R.; Du, P.; Lin, H.; Fu, X.; Niu, Q.; Yin, C. The Influence of Different Shear Directions on the Shear Resistance Characteristics of Rock Joints. Buildings 2023, 13, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z. Numerical Analysis Method of Shear Properties of Infilled Joints under Constant Normal Stiffness Condition. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1642146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Spearing, A.J.S.; Jessu, K. Analysis of the Combined Load Behaviour of Rock Bolt Installed Across Discontinuity and Its Modelling Using FLAC3D. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 5867–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Compressive Strength (/MPa) | Elastic Modulus (E/Gpa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Shear Modulus (G/GPa) | Internal Friction Angle (°) | Normal Stiffness (kn) | Shear Stiffness (ks) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft rock | SR1 | 10 | 5 | 0.3 | 1.92 | 20 | 27.47 | 4.81 |

| SR2 | 20 | 10 | 0.3 | 3.85 | 20 | 54.95 | 9.62 | |

| SR3 | 19.23 | 15 | 0.3 | 5.77 | 20 | 82.42 | 14.42 | |

| SR4 | 40 | 20 | 0.3 | 7.69 | 20 | 109.89 | 19.23 | |

| SR5 | 50 | 25 | 0.3 | 9.62 | 20 | 137.36 | 24.04 | |

| Moderately hard rock | MR1 | 60 | 30 | 0.25 | 12.00 | 40 | 160.00 | 30.00 |

| MR2 | 70 | 35 | 0.25 | 14.00 | 40 | 186.67 | 35.00 | |

| MR3 | 80 | 40 | 0.25 | 16.00 | 40 | 213.33 | 40.00 | |

| MR4 | 90 | 45 | 0.25 | 18.00 | 40 | 240.00 | 45.00 | |

| MR5 | 100 | 50 | 0.25 | 20.00 | 40 | 266.67 | 50.00 | |

| MR6 | 110 | 55 | 0.25 | 22.00 | 40 | 293.33 | 55.00 | |

| MR7 | 120 | 60 | 0.25 | 24.00 | 40 | 320.00 | 60.00 | |

| Hard rock | HR1 | 130 | 65 | 0.2 | 27.08 | 50 | 338.54 | 67.71 |

| HR2 | 140 | 70 | 0.2 | 29.17 | 50 | 364.58 | 72.92 | |

| HR3 | 150 | 75 | 0.2 | 31.25 | 50 | 390.63 | 78.13 | |

| HR4 | 160 | 80 | 0.2 | 33.33 | 50 | 416.67 | 83.33 | |

| HR5 | 170 | 85 | 0.2 | 35.42 | 50 | 442.71 | 88.54 | |

| HR6 | 180 | 90 | 0.2 | 37.50 | 50 | 468.75 | 93.75 | |

| HR7 | 190 | 95 | 0.2 | 39.58 | 50 | 494.79 | 98.96 | |

| HR8 | 200 | 100 | 0.2 | 41.67 | 50 | 520.83 | 104.17 | |

| HR9 | 210 | 105 | 0.2 | 43.75 | 50 | 546.88 | 109.38 | |

| HR10 | 220 | 110 | 0.2 | 45.83 | 50 | 572.92 | 114.58 | |

| HR11 | 230 | 115 | 0.2 | 47.92 | 50 | 598.96 | 119.79 | |

| HR12 | 240 | 120 | 0.2 | 50.00 | 50 | 625.00 | 125.00 | |

| HR13 | 250 | 125 | 0.2 | 52.08 | 50 | 651.04 | 130.21 | |

| HR14 | 260 | 130 | 0.2 | 54.17 | 50 | 677.08 | 135.42 | |

| HR15 | 270 | 135 | 0.2 | 56.25 | 50 | 703.13 | 140.63 | |

| HR16 | 280 | 140 | 0.2 | 58.33 | 50 | 729.17 | 145.83 | |

| HR17 | 290 | 145 | 0.2 | 60.42 | 50 | 755.21 | 151.04 | |

| HR18 | 300 | 150 | 0.2 | 62.50 | 50 | 781.25 | 156.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, G.; Dai, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhao, L. Shear Mechanism Differentiation Investigation of Rock Joints with Varying Lithologies Using 3D-Printed Barton Profiles and Numerical Modeling. Geotechnics 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010008

Chen Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Lv G, Dai Q, Liu L, Zhao L. Shear Mechanism Differentiation Investigation of Rock Joints with Varying Lithologies Using 3D-Printed Barton Profiles and Numerical Modeling. Geotechnics. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yue, Yinsheng Wang, Yongqiang Li, Guoshun Lv, Quan Dai, Le Liu, and Lianheng Zhao. 2026. "Shear Mechanism Differentiation Investigation of Rock Joints with Varying Lithologies Using 3D-Printed Barton Profiles and Numerical Modeling" Geotechnics 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010008

APA StyleChen, Y., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Lv, G., Dai, Q., Liu, L., & Zhao, L. (2026). Shear Mechanism Differentiation Investigation of Rock Joints with Varying Lithologies Using 3D-Printed Barton Profiles and Numerical Modeling. Geotechnics, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010008