Study on Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Activated MgO Carbonation Curing of Tidal Mudflat Sediments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

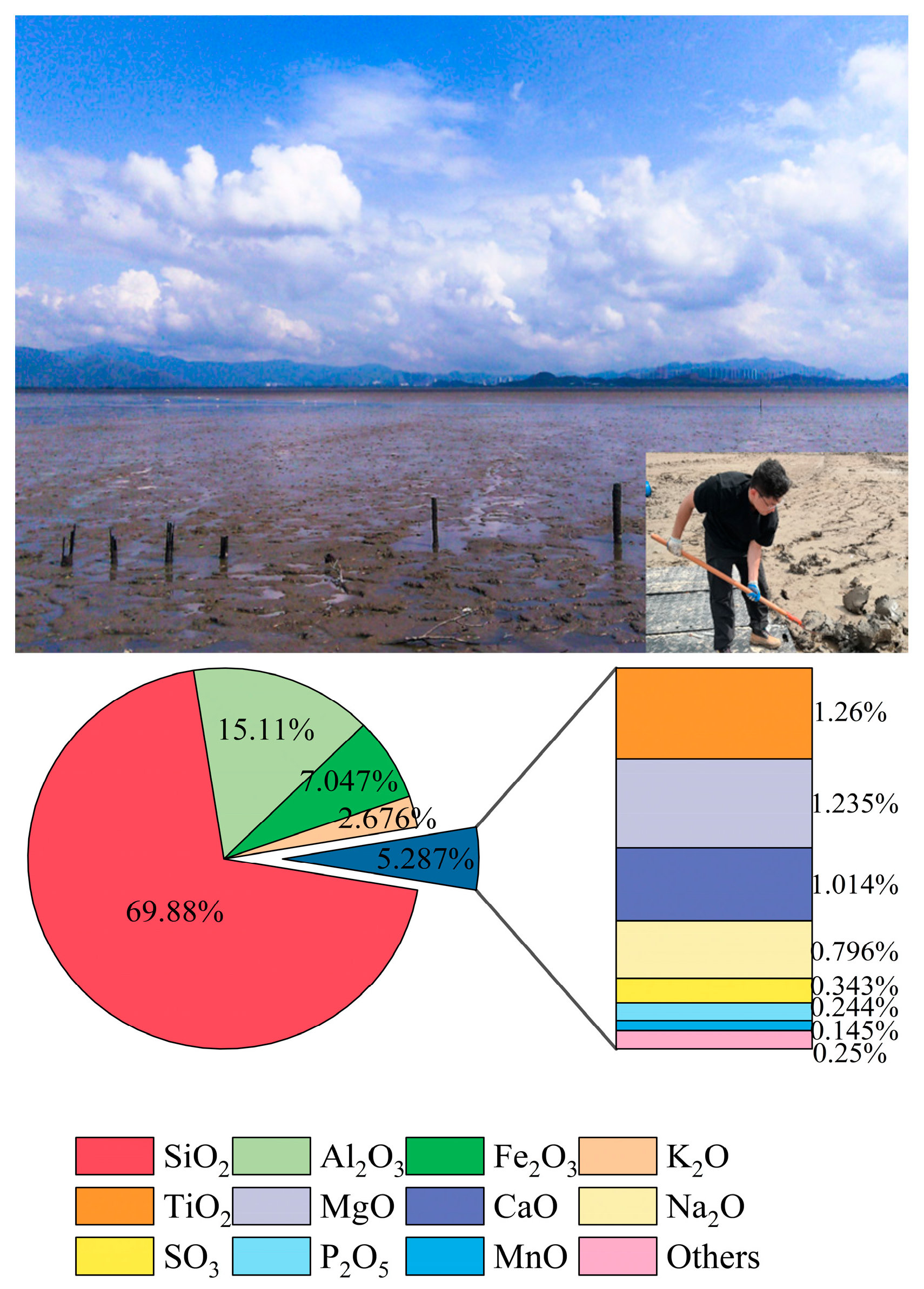

2.1. Materials

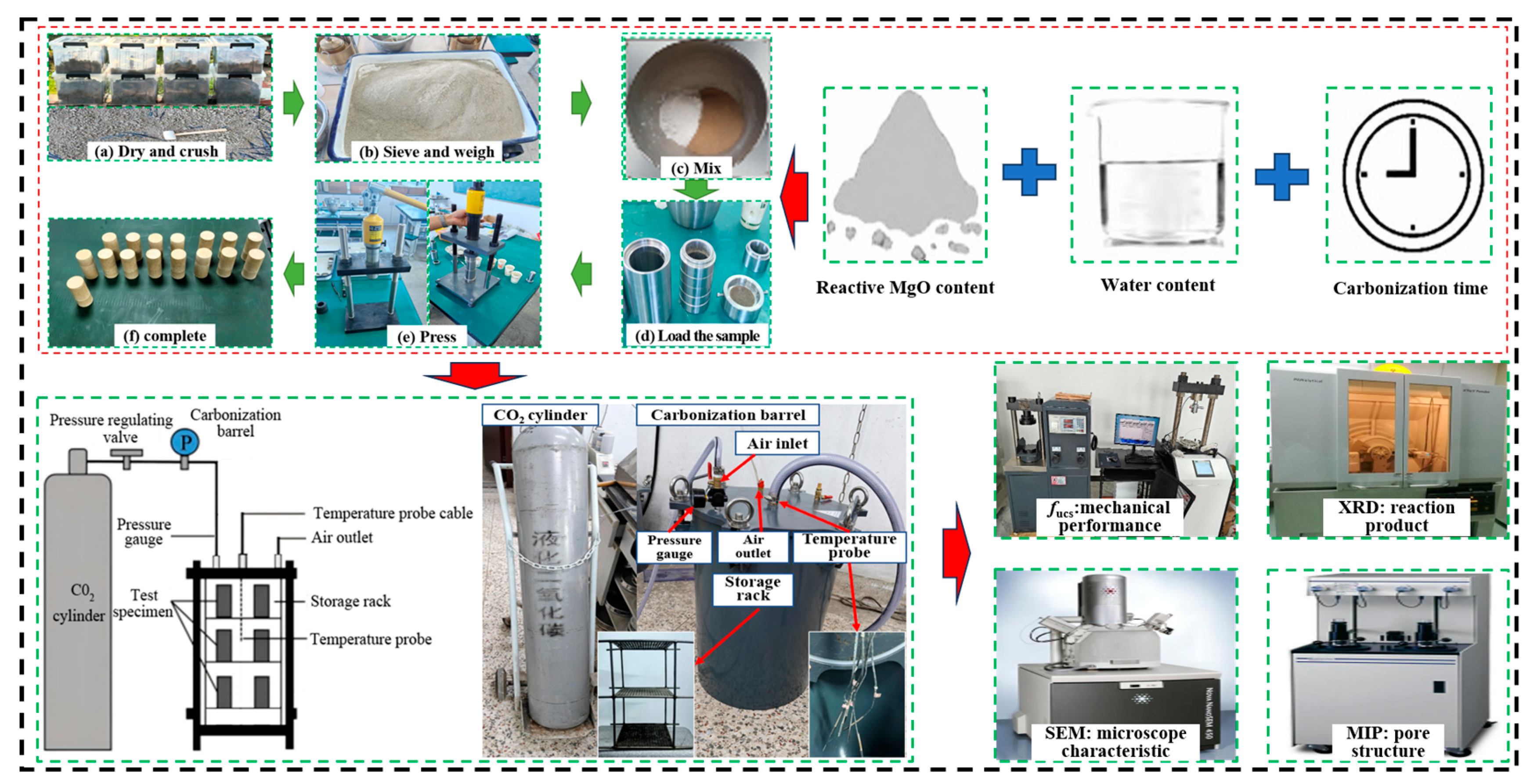

2.2. Test Methods

3. Performance and Influencing Factors of Carbonated Stabilization of Tidal Mudflat Sediments

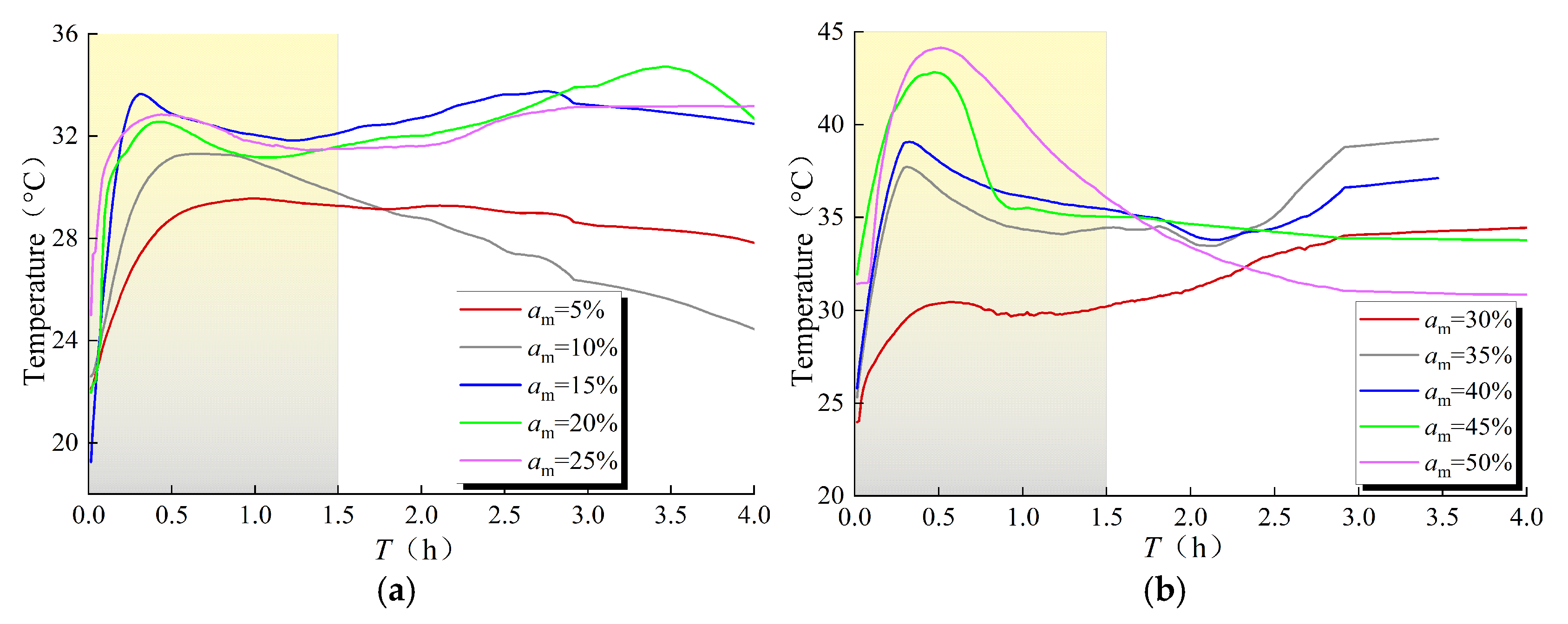

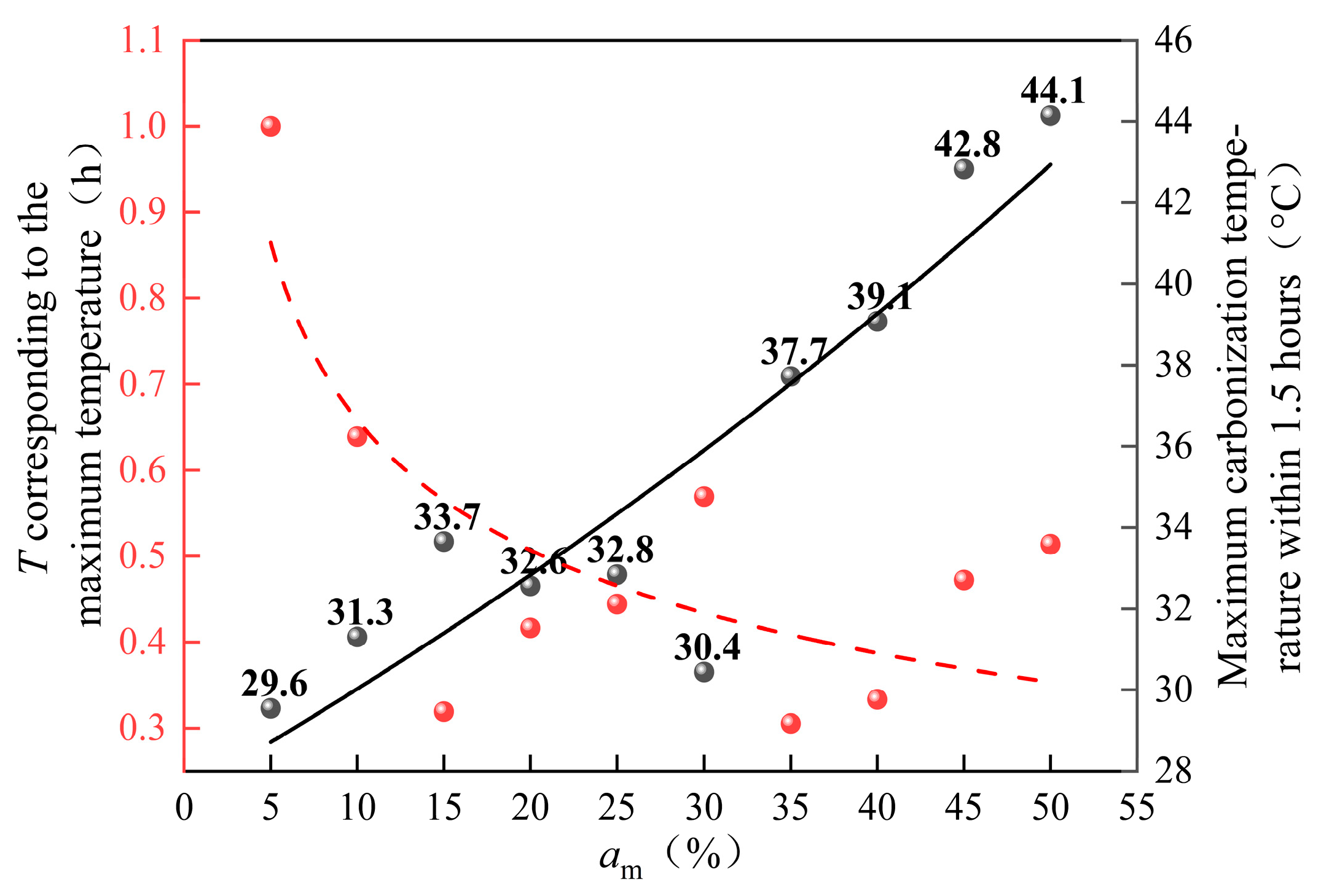

3.1. Variation of Reaction Temperature

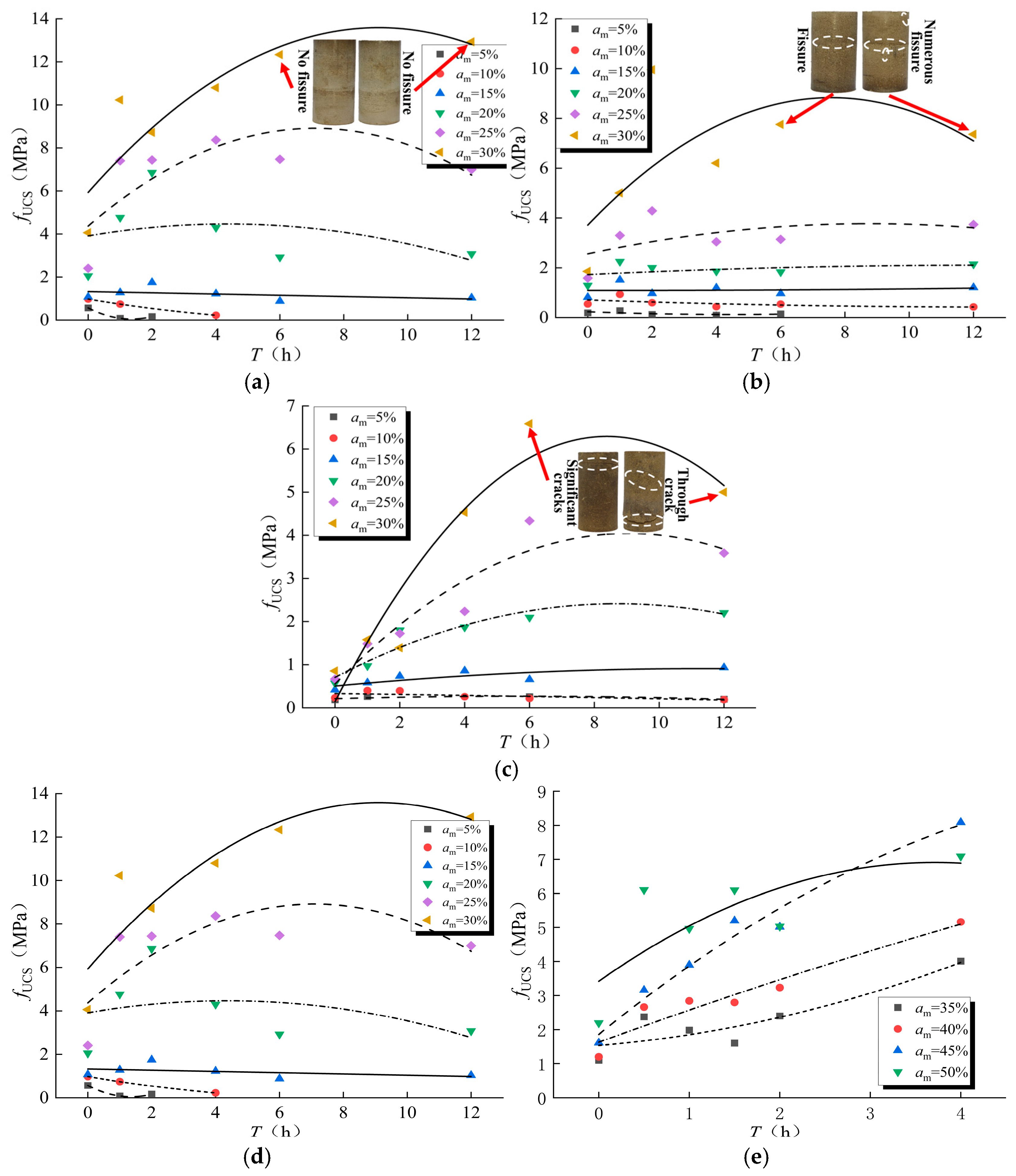

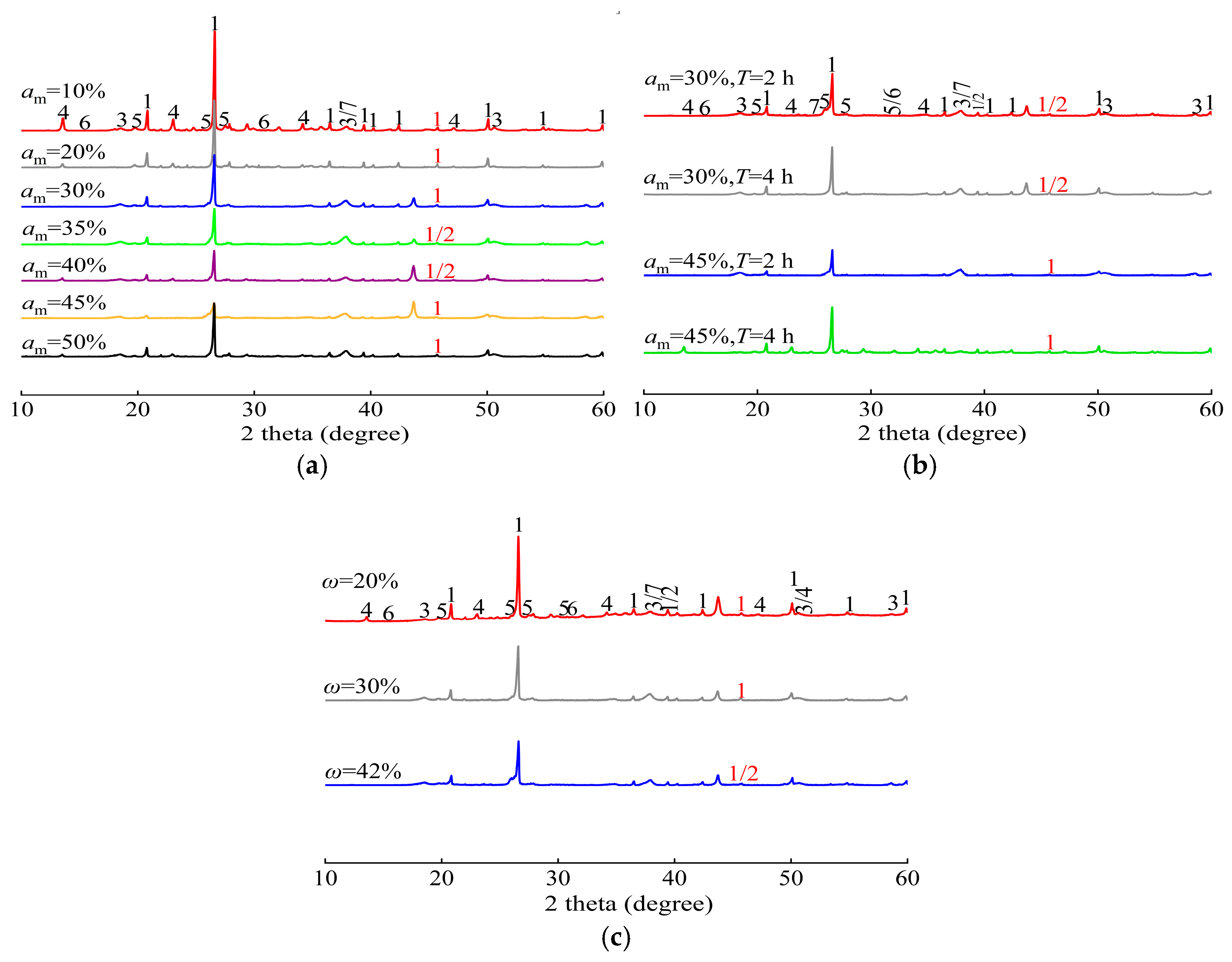

3.2. Variation of UCS

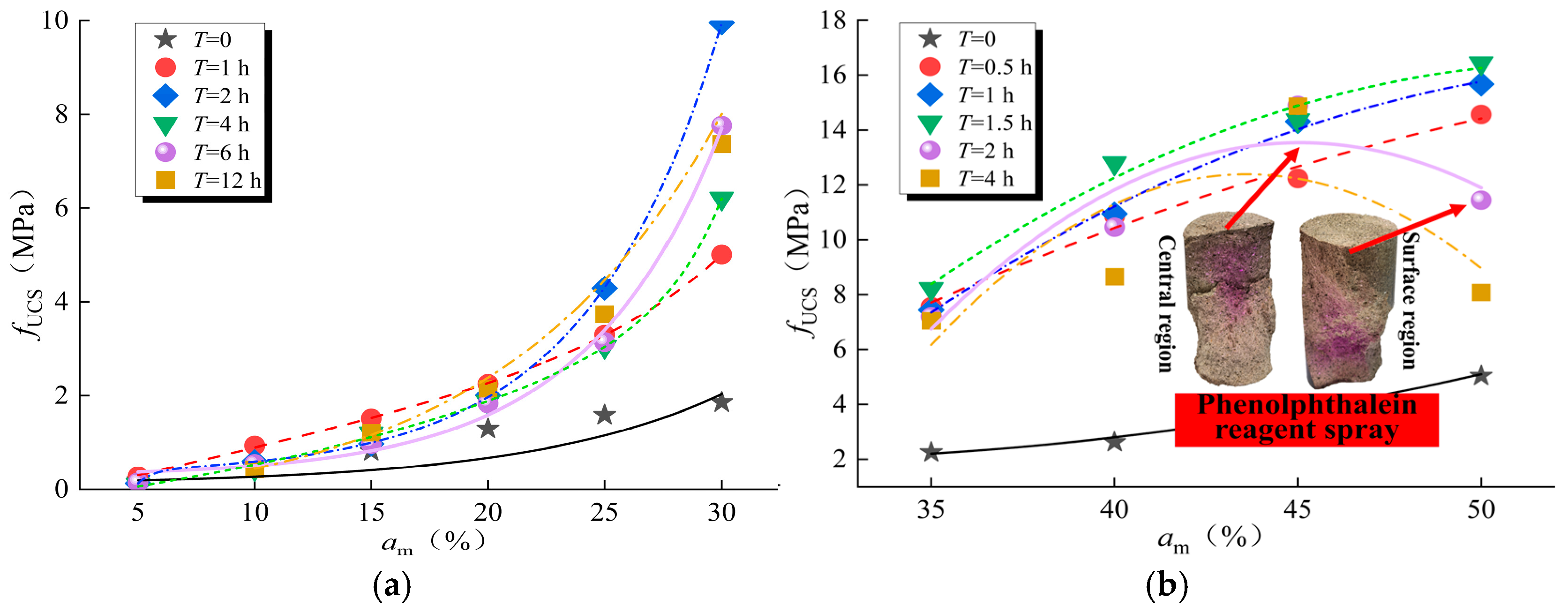

3.3. Variation of Deformation Modulus

4. Micro-Mechanisms Underlying Carbonated Stabilization of Tidal Mudflat Sediments

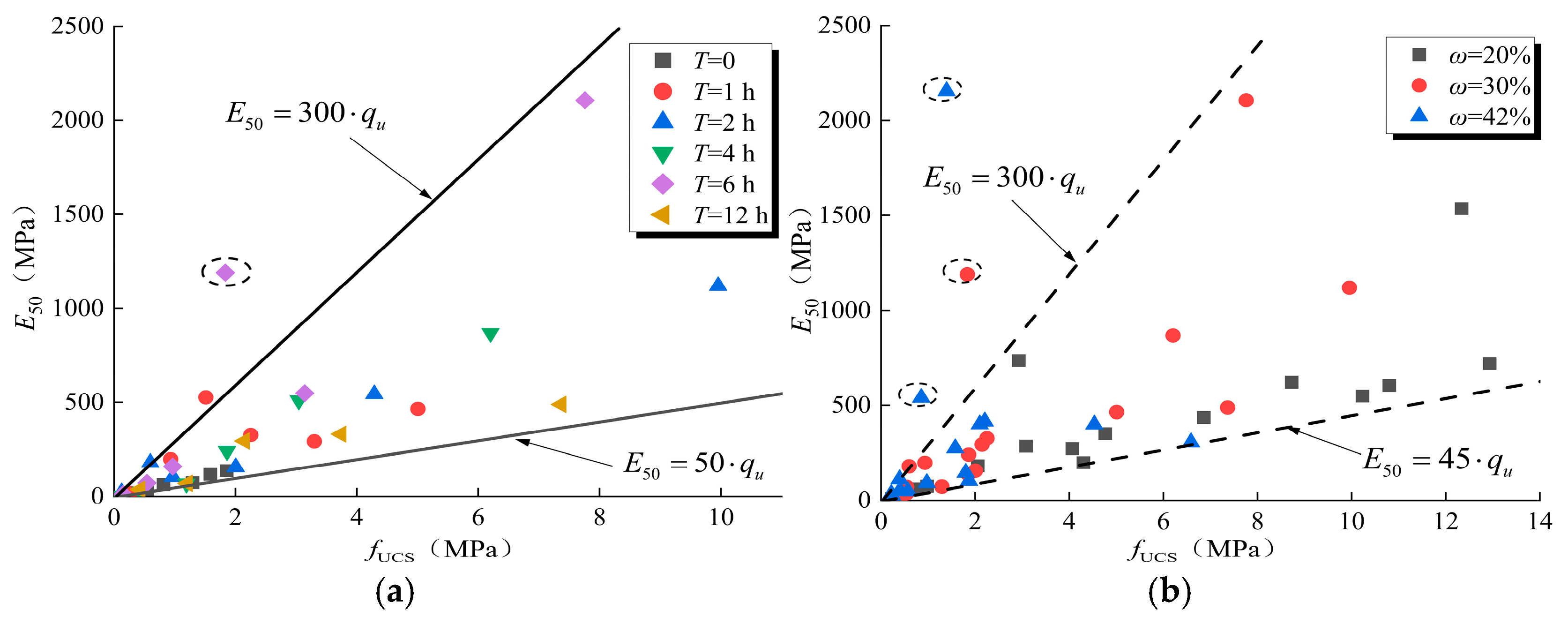

4.1. Phase Composition Analysis

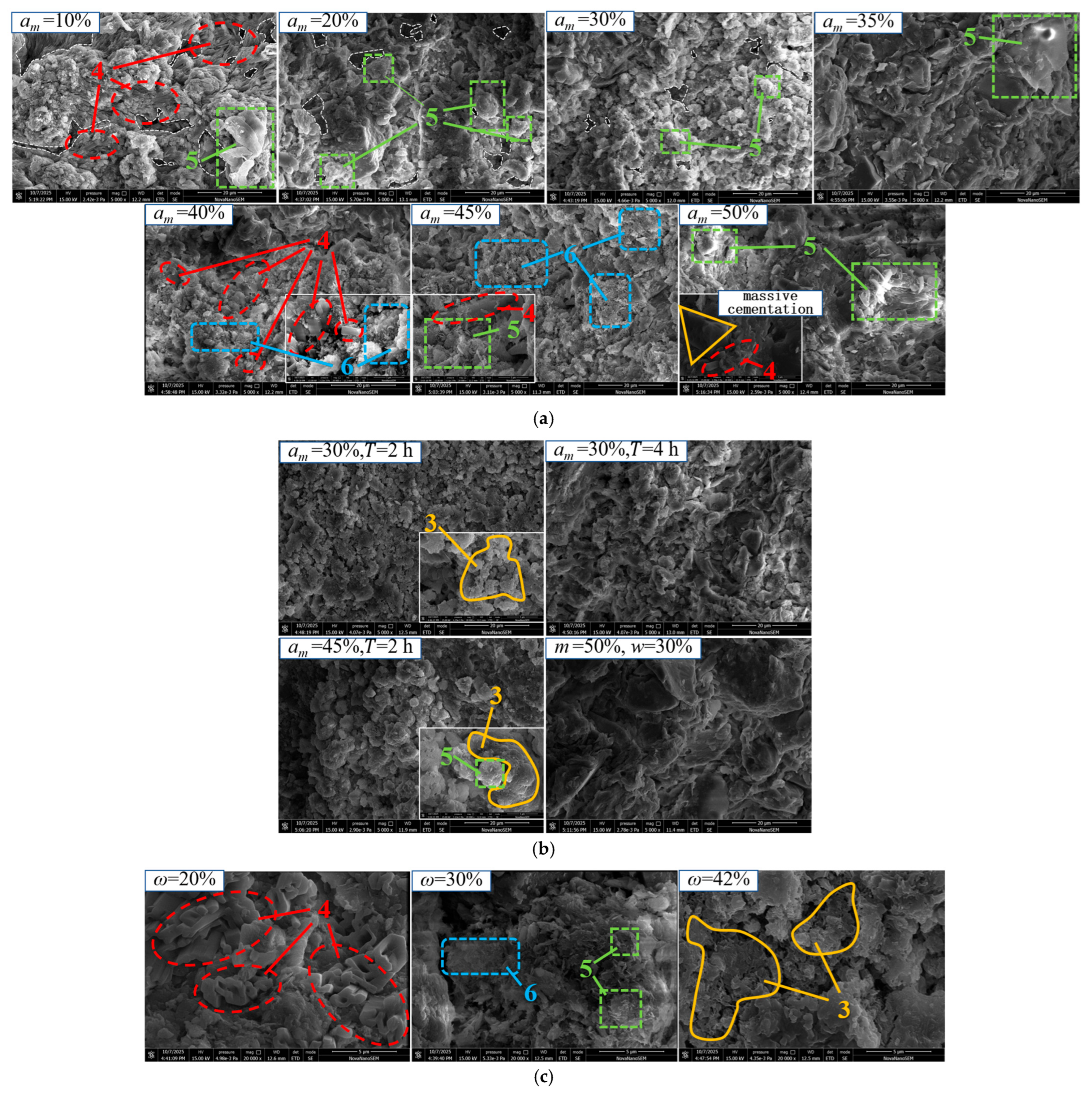

4.2. Development of Microstructural Fabric

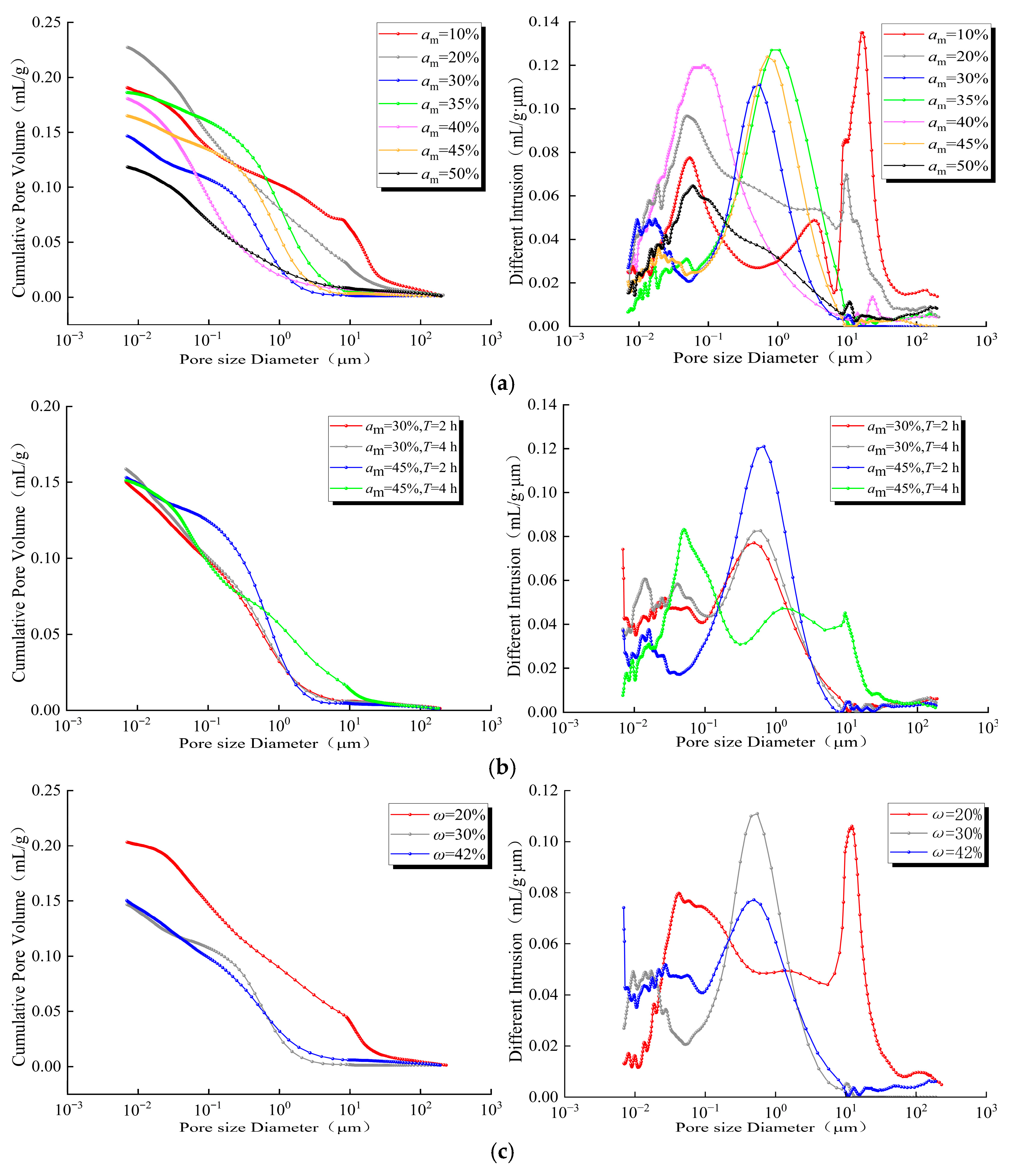

4.3. Multiscale Pore Structure Evolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Capacity Statistics 2025; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Masdar City, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Zheng, T. Study on constitutive model parameters of hardening soil for typical silt soil in the Pearl River Delta region. China Harb. Eng. 2024, 1, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Experimental study on the influence of loading methods on consolidation characteristics of muddy soil. North. Build. 2025, 10, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, B.; Pan, H.; Wang, K. Experimental study on mechanical properties of offshore gassy clay—Taking Jiaxin NO. 1 offshore wind farm as an example. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2023, 44, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wen, X.; Wu, J.; Wen, W.; Li, C.; Sun, Z. Experimental investigation on consolidation of soft soil in mudflat of offshore wind farm based on MICP technology. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Application of sludge solidification technology in river dredging project. Hydro Sci. Cold Zone Eng. 2024, 2, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xue, D.; Peng, M.; Chen, Y. Experiment on modified-curing and strength properties of waste mud from slurry shield tunnel. J. Eng. Geol. 2018, 26, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Bian, Y.; Min, F.; Zhu, W. Improvement of metro shield muck to controlled low-strength material. China Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 53, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Xia, B.; Wang, N. Mechanism of electro-chemical stabilization for modifying Zhuhai soft clay. Rock Soil Mech. 2025, 46, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, S.; Cai, G. Study on the rapid carbonization and stabilization technique and its micromechanism of muddy soil. J. Ground Improv. 2020, 2, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, F.; Shen, Z.; Li, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, J.; Li, K. Solidification and carbonization experimental study on magnesium oxide in shield waste soil and its carbonization mechanism. Rock Soil Mech. 2024, 45, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Li, W.; He, M.; Liang, Q.; Jiang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhong, P.; Chen, Y. Process reengineering for in-situ carbon capture in the cement industry and its demonstration application under the dual-carbon policy framework. Cem. Guide New Epoch. 2025, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liang, Y.; Cui, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S. Influencing factors and mechanism of dredged sediment carbonated and solidified with reactive MgO. J. Build. Mater. 2024, 27, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Physico-mechanical properties of clay stabilized by magnesium oxide-mediated indirect carbonation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 47, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ban, R.; Song, Y.; Li, H.; Pan, Z.; Wang, J. Effect of initial water content on characteristics of reactive MgO carbonated red clay. China Sci. 2022, 17, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Cai, G.; Zhong, Y.; Du, G. Experimental study of carbide slag-MgO stabilized mud under carbonation condition. Sci. Technol. Ind. 2023, 23, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Min, F.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, B. Mechanism and performance of recycled shield spoil treated by MgO stabilization-carbonation for sustainable subgrade construction. China J. Highw. Transp. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Shen, K.; Mao, T.; Xiao, L.; Zhuang, J. Experimental research on the carbonation granulation method for silty drilling residue and its strength growth mechanism. China J. Highw. Transp. 2024, 37, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ding, S.; Chen, K.; Jiang, J.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J. Dissolution characterization of zinc-contaminated soils cured by activated magnesium oxide based on carbonation. Rock Soil Mech. 2025, 46, 92–105+120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, H.; Li, M.; Zheng, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Factors and mechanism research of carbonation mineralization with MgO in recycled fine aggregate. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 55, 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H. Mechanical properties and strength prediction model of cement stabilized beach silt in Ningbo city. Low Temp. Archit. Technol. 2020, 42, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Dan, Z.; Cai, Z.; Hong, Y. In-situ behaviour of sensitive clayey ground subjected to high pressure jet grouting for planned offshore wind farm. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2021, 42, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- JTG 3430-2020; Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; People’s Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Cai, G. Micro-mechanism of silty clay solidified by carbonation of reactive magnesia. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 1543–1552+1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Liu, S.; Cao, J. Micro-mechanism of silt solidified by carbonation of reactive magnesia oxide. China Civ. Eng. J. 2017, 50, 105–113+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Theory and Technology of Carbonation Solidification for Soft Soils; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Jin, F.; Singh, D.; Puppala, A. Engineering properties and microstructural characteristics of cement-stabilized zinc-contaminated kaolin. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wei, M.; Jin, F.; Zhi, B. Stress-strain relation and strength characteristics of cement treated zinc-contaminated clay. Eng. Geol. 2013, 167, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Chen, W.; Yin, J.; Wu, P.; Tsang, D. Stress-Strain behaviour of Cement-Stabilized Hong Kong marine deposits. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 122103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 79-2012; Technical Code for Ground Treatment of Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Liska, M. Performance of Reactive Magnesia Cement and Porous Construction Products. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.L. New Technology and Theory of Mixing Pile Based on Sustainable Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, L.; Luo, B.; Zhang, Q. Research on preparation and morphology evolution of magnesium carbonate tri-hydrate. J. Synth. Cryst. 2014, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Hong, Z.; Liu, S. Microstructure study of flow-solidified soil of dredged clays by mercury intrusion porosimetry. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 3591–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kong, L. Characterization of pore features of marine clay by SEM, MIP and nitrogen adsorption method. Rock Soil Mech. 2013, 34, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Shao, H.; Zeng, H.; Gao, B.; Jiang, H. Formation mechanisms of nano-scale pores/fissures and shale oil enrichment characteristics for Gulong shale, Songliao Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 1350–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50007-2011; Code for Design of Building Foundation. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

| Soil Type | Particle Size Distribution/% | Natural Moisture Content (%) | Specific Gravity | Dry Density (g/cm3) | Void Ratio | Liquid Limit (%) | Plastic Limit (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mucky soil | >75 μm | 75–5 μm | 5–2 μm | <2 μm | 42 | 2.74 | 1.27 | 1.18 | 39.1 | 22.5 |

| 0.8 | 74.8 | 12.8 | 11.6 | |||||||

| Test Program | MgO Content am (%) | Carbonation Duration T (h) | Initial Moisture Content ω (%) | Number of Test Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction temperature | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 | 4 | 42 | 10 |

| UCS/Deformation modulus | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 | 20, 30, 42 | 180 |

| 35, 40, 45, 50 | 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4 | |||

| Microstructural analysis (XRD, SEM, MIP) | 10, 20, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 | 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4 | 20, 30, 42 | 72 |

| Mineral Name | Chemical Formula | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz | SiO2 | 1 |

| Periclase | MgO | 2 |

| Brucite | Mg(OH)2 | 3 |

| Nesquehonite | MgCO3·3H2O | 4 |

| Dypingite | Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·5H2O | 5 |

| Hydromagnesite | Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·4H2O | 6 |

| Clinochrysotile | Mg3Si2O5(OH)4 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Guo, L.; Shao, Z.; Li, E. Study on Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Activated MgO Carbonation Curing of Tidal Mudflat Sediments. Geotechnics 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010004

Lu H, Zhang Q, Bai Z, Guo L, Shao Z, Li E. Study on Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Activated MgO Carbonation Curing of Tidal Mudflat Sediments. Geotechnics. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Hui, Qiyao Zhang, Zhixiao Bai, Liwei Guo, Zeyu Shao, and Erbing Li. 2026. "Study on Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Activated MgO Carbonation Curing of Tidal Mudflat Sediments" Geotechnics 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010004

APA StyleLu, H., Zhang, Q., Bai, Z., Guo, L., Shao, Z., & Li, E. (2026). Study on Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Activated MgO Carbonation Curing of Tidal Mudflat Sediments. Geotechnics, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics6010004