1. Introduction

In the context of accelerating climate change and increasingly frequent environmental crises, young people are emerging as crucial agents of change [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Their voices, creativity, and commitment to sustainability are essential for shaping future resilience strategies in both natural and urban systems. However, meaningful participation requires not only awareness but also dedicated spaces for dialogue, learning, and action.

International frameworks strongly emphasize the role of youth in climate governance. The 2015 Paris Agreement explicitly calls for the engagement of future generations, while the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

5] underline the importance of education and participation as key enablers of sustainable development. Similarly, European policies promote youth involvement through programs such as Town Twinning, which fosters cross-border collaboration between municipalities to address shared challenges, including climate resilience [

6].

Despite this policy support, there remains a persistent gap in translating high-level objectives into structured, place-based educational practices capable of fostering both climate literacy and civic agency among youth. Numerous studies highlight that existing initiatives tend to be fragmented, short-term, and insufficiently embedded in local governance frameworks, thus limiting their long-term transformative potential [

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, while participatory and place-based approaches have been shown to be particularly effective in linking global environmental challenges to students’ lived realities [

10], there is still limited empirical evidence on transnational models that combine scientific knowledge, experiential methods, and civic engagement in a coherent framework [

11,

12,

13].

Against this backdrop, the “Youth Participation in Creating Resilient Cities” project was launched in November 2023 under the EU-funded Town Twinning II—For a Green Future program. The project involved high school students from Cinisello Balsamo (Italy) and Edremit (Turkey) in a transnational educational path combining scientific seminars, experiential learning, and participatory activities. By situating climate challenges in both local contexts (i.e., glacier retreat in the Alps and coastal vulnerability in the Aegean region), the project offered young people the opportunity to connect global climate dynamics with their lived environments and to contribute to local resilience strategies.

The project was designed to enhance youth engagement in climate action through a structured program of local and transnational activities. It focused on empowering high school students to understand the causes and consequences of climate change (particularly its impact on glaciers) and to promote civic involvement in environmental decision-making. The educational design was built around the concept of participatory learning, in which young people were not merely passive recipients but active co-creators of knowledge and solutions. Through the formation of Youth Climate Councils, students developed concrete proposals for local climate actions and directly engaged with public institutions.

Town Twinning is a European Union initiative that promotes cooperation between municipalities across borders, with the aim of building mutual understanding and jointly addressing common challenges. While originally focused on cultural exchange, in recent years Town Twinning has increasingly supported projects related to sustainability, education, and climate action. This framework provided an ideal basis for our project, enabling two municipalities with different geographical and cultural contexts to collaborate on youth engagement in climate resilience.

The aims of this study are threefold: (i) to assess whether a transnational, participatory approach can improve students’ climate knowledge and civic engagement; (ii) to explore the role of digital and immersive tools in supporting climate literacy; and (iii) to examine Youth Climate Councils as a mechanism for enhancing youth participation in local governance.

By pursuing these objectives, this paper contributes to filling the research and practice gap on youth climate education. It demonstrates how cross-sector collaboration between academia, local governments, and NGOs can generate a replicable framework that integrates place-based climate education into urban governance and youth policy.

Geographical Contexts

The project was implemented in two geographically and culturally distinct municipalities, both strongly committed to sustainability and youth policy.

Cinisello Balsamo, located on the northern outskirts of Milan, Italy, is an urban municipality of about 75,000 residents. It is recognized for its commitment to social inclusion, urban regeneration, and environmental sustainability. Although the city has undergone significant land consumption and urbanization over the past three decades [

14], it is now actively promoting green mobility and public participation, making it a notable example of civic innovation.

Edremit, located on Turkey’s Aegean coast in Balıkesir Province, has a population of about 167,900 [

15]. The district is characterized by a strong agricultural heritage and is particularly renowned for its olive oil and the “Yeşil Çizik” olive, both protected as PDO/IGP products by the European Union. At the same time, the local administration is actively engaged in EU cooperation. Its Municipal Foreign Relations Office coordinates youth and civic engagement initiatives, including Erasmus+, the European Solidarity Corps, and Eurodesk contact point candidacies [

16].

Despite their geographical and cultural differences, both municipalities were united by a common objective: empowering the next generation to engage in climate resilience efforts.

The partnership involved two key institutions that anchored the project (i.e., the University of Milan (UNIMI) and Fondazione Legambiente Innovazione).

The University of Milan (UNIMI, particularly its Department of Environmental Science and Policy), which provided scientific leadership, developed the educational curriculum and delivered seminars. As a member of the League of European Research Universities (LERU; see

https://www.leru.org/, accessed on 15 September 2025), the University contributed high-level research expertise and teaching capacity.

Fondazione Legambiente Innovazione, affiliated with Italy’s most prominent environmental NGO, contributed its long-standing expertise in civic engagement, non-formal education, and participatory methodologies. Legambiente facilitated youth workshops, mentoring, and environmental advocacy activities.

This strategic collaboration between local governments, academia, and civil society was fundamental to the project’s success and represents a strong model for other cities seeking to replicate the approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Project Structure

The Twinning project adopted a participatory and experiential learning approach to engage high school students in climate change education. The methodology was framed around four interrelated phases that progressively guided participants from awareness to action: (i) engagement and awareness through introductory seminars and interactive activities; (ii) capacity building via workshops and group exercises; (iii) the formation of Youth Climate Councils, where students identified local issues and developed proposals; and (iv) implementation and dissemination through student-led initiatives and communication tools. This framework ensured that students were not only introduced to scientific concepts but also encouraged to co-design solutions and communicate them to a broader audience.

2.2. Educational Techniques

Across both Italy and Turkey, a set of participatory techniques was used to complement traditional lectures. Visual illustrations and videos supported scientific explanations, while interactive icebreakers facilitated group cohesion. Practical tools such as carbon footprint calculators [

17] allowed students to connect global concepts with their own lifestyles. Immersive technologies, including 360° virtual reality [

18], enabled a direct experiential understanding of glacier retreat. Non-formal formats such as the World Café and role-playing games promoted dialogue, negotiation, and perspective-taking, while continuous mentorship by academics and NGO practitioners supported the refinement of student proposals.

Taken together, these techniques provided a dynamic learning environment that moved beyond passive knowledge transfer. They encouraged critical thinking, active participation, and the co-construction of solutions, aligning with the project’s broader objective of empowering young people to become agents of climate resilience.

2.3. Activities in Italy

In Cinisello Balsamo, three thematic seminars were held on 7, 8, and 10 May 2024, at the Il Pertini Cultural Center, a civic and educational hub. A total of 24 students from Liceo Casiraghi, a public scientific high school, took part in the activities.

On the first seminar day, Understanding Climate Mechanisms, two professors of atmospheric physics from University of Milan introduced the physics of climate change, the role of greenhouse gases, and the interpretation of historical atmospheric data. As part of the practical activities, students calculated their individual carbon footprint using a digital webapp [

17] and discussed possible mitigation strategies at the personal level.

On the second seminar day, Glacier Retreat and Immersive Exploration, two professors of glaciology from University of Milan focused on global and local glacier changes. Using 360° virtual reality headsets, students virtually visited the Forni Glacier in Stelvio National Park, strengthening both scientific understanding and emotional connection to glacial environments [

18]. Evaluation and enjoyment questionnaires were administered at the end of the session.

The third seminar, Solutions and Youth Proposals, engaged students in simulated international negotiations. Divided into groups representing different countries (e.g., USA, China, Sudan, The Netherlands), they developed national action plans and presented them to peers, who voted on the proposals. Certificates were distributed at the conclusion of the activity.

To assess knowledge acquisition in Italy, a final test consisting of eight multiple-choice questions was administered at the end of the three-day seminar (

Table 1). Twenty-four students from Liceo Casiraghi completed the test. Each question was scored as 1 for a correct answer and 0 for an incorrect one, with a maximum possible score of 8. The test provided a quantitative measure of students’ understanding of climate change concepts and complemented the qualitative feedback collected through evaluation and enjoyment questionnaires.

At the end of the Italian seminars, students were asked to complete a teaching evaluation questionnaire to assess the overall quality of the educational activities (

Table 2). The survey included seven items covering prior knowledge, coherence of topics, adequacy of time allocation, clarity and engagement of lecturers, and overall satisfaction. Responses were collected anonymously on a four-point Likert scale (Strongly agree, Mostly agree, Mostly disagree, Strongly disagree).

2.4. Activities in Turkey

From 5 to 7 August 2024, a three-day training seminar was held at the Atatürk Youth Center in Edremit, involving approximately 20 high school students recruited through the municipality.

On the first day, Scientific Foundation, a professor of atmospheric sciences and meteorology from Balıkesir University introduced the greenhouse effect, historical climate trends, and international climate policy frameworks.

The second day, Carbon and Community, explored concepts such as CO2 emissions, the carbon footprint, and planetary boundaries. Through a World Café format, students discussed practical climate actions in everyday contexts, including at home, in schools, and in public transport.

The third day, Policy and Participation, featured workshops on Turkish climate policies and a participatory city redesign exercise, during which students developed budgeted solutions to address local climate challenges in Edremit.

To evaluate learning outcomes, an identical pre-test and a post-test were administered at two different stages of the program (

Table 3). The pre-test was completed by 16 students in the morning of the first day, before the start of the seminar activities, while the post-test was completed by 17 students in the afternoon of the final day, immediately after the conclusion of the seminar.

Both questionnaires consisted of the same set of multiple-choice and true/false questions covering fundamental concepts such as the greenhouse effect, greenhouse gases, international climate agreements, and the societal impacts of climate change. Since the items were identical, it was possible to compare performance both at the level of individual questions and overall scores. Each correct answer was scored as 1 and each incorrect answer as 0, with a maximum possible score of 10. Average test scores and standard deviations were calculated, and the percentage of correct responses for each item was also analyzed to provide a more detailed picture of learning gains.

At the end of the Edremit seminar, students were invited to complete an evaluation questionnaire to assess the quality of the teaching activities (

Table 4). The survey included Likert-scale items (1 = very poor, 5 = excellent) on clarity and usefulness of the content, time allocation, teaching methods, trainers’ communication skills, and the adequacy of the venue. In addition, open-ended questions collected qualitative feedback on strengths, areas for improvement, and expectations from the municipality.

All responses were collected anonymously, and no sensitive personal data were involved, in line with national and institutional ethical standards.

3. Results

A total of 41 high school students participated in the Twinning project activities, with 24 students involved in Italy and 17 in Turkey. Italian participants were recruited from Liceo Casiraghi, a public scientific high school in Cinisello Balsamo, while Turkish participants were selected through the Edremit Municipality’s Atatürk Youth Center. Most students were between 16 and 18 years old and took part voluntarily through their schools.

3.1. Learning Outcomes

In Italy, knowledge acquisition was assessed through a final test administered at the end of the three-day seminar. Twenty-four students from Liceo Casiraghi completed an eight-question multiple-choice test. The average score was 6.29 (SD = 1.43) out of 8, corresponding to approximately 79% correct answers. Scores ranged from 1 to 8, with 2 students achieving full marks and 12 with 7 out of 8. These results suggest that the combination of lectures, practical tools, and immersive experiences contributed effectively to strengthening students’ understanding of climate change concepts.

In Turkey, learning outcomes were evaluated through a pre/post knowledge test administered to high school students attending the three-day seminar in Edremit. The pre-test, taken by 16 students on the first morning, yielded an average score of 8.19 (SD = 0.98) out of 10, while the post-test, completed by 17 students at the end of the seminar, showed a higher mean score of 9.24 (SD = 0.75). This corresponds to an average improvement of +1.05 points. The pre-test (n = 16) and post-test (n = 17) contained identical items, allowing for direct comparison. The consistent increase in mean scores indicates that the seminar effectively improved students’ knowledge of climate change.

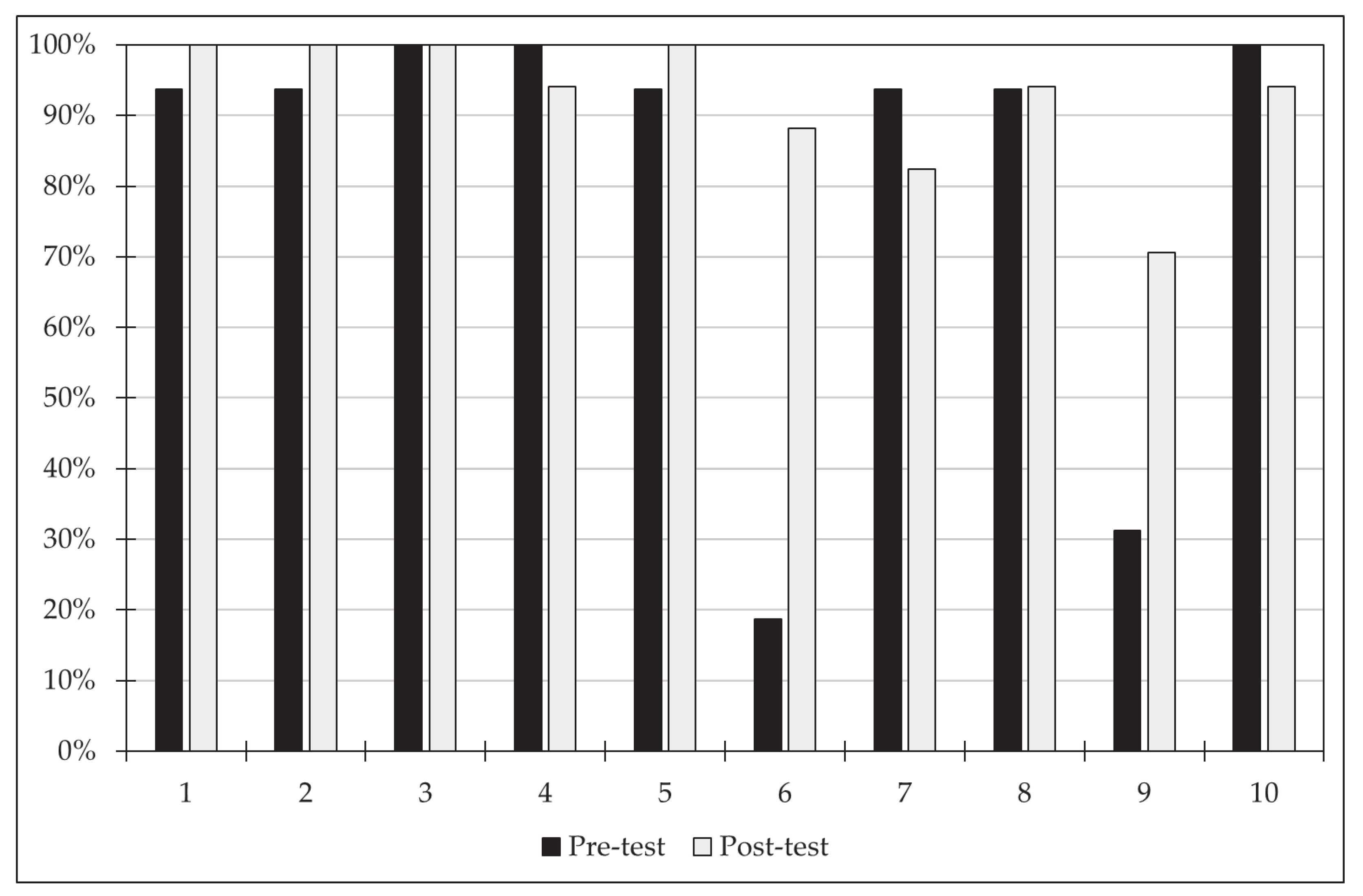

The item-level comparison confirms that students improved their performance on most questions between the pre- and post-test (

Figure 1). Notable gains were observed for knowledge of the Paris Climate Agreement (+69.5%) and the identification of the first international meeting on climate change (+39.3%). Smaller improvements were recorded for items related to the greenhouse effect, alternative terminology, and greenhouse gases (about +6% each). These modest gains reflect the fact that most students had already answered these questions correctly in the pre-test, leaving limited room for further improvement. By contrast, two items showed a slight decrease in the percentage of correct responses: the role of fossil fuels (−5.9%) and the impacts of climate change on human health (−5.9%). These reductions can be explained by the higher number of respondents in the post-test (17 vs. 16): the additional student compared to the pre-test could answer incorrectly, lowering the overall percentage despite stable performance among the others. Overall, the consistency of results across questions, combined with strong improvements on key policy-related items, demonstrates that the seminar significantly enhanced students’ understanding of climate change.

Beyond the overall improvement in knowledge, the analysis of individual questions highlights specific areas where students faced greater difficulties. In the pre-test, the lowest rate of correct answers (18.8%) was observed for the question concerning the main decision adopted in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, suggesting limited familiarity with international climate policy frameworks at the outset of the seminar. By contrast, in the post-test, the question that yielded the highest number of incorrect responses was related to the identification of the first international meeting addressing climate change, namely the Kyoto Protocol, which was correctly recognized by 70.6% of participants. These findings indicate that while the seminar substantially improved general climate knowledge, international policy milestones remained relatively challenging for students.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that both the Italian and Turkish activities produced measurable learning gains, complementing the qualitative feedback collected from participants.

3.2. Evaluation of Teaching Quality

In Italy, the evaluation questionnaire completed by 13 students provided useful insights into the perceived quality of the seminars. The clarity and expertise of the lecturers were rated very positively: ten students responded “Strongly agree” and three “Mostly agree” when asked whether the topics were presented clearly and thoroughly. Similarly, twelve students considered the lecturers to be very available and supportive. Interest and engagement were also evaluated favorably, with six students answering “Strongly agree” and five “Mostly agree”, although two reported limited stimulation. With respect to the coherence of topics with the project’s objectives, eight students expressed “Strongly agree”, two “Mostly agree”, and three “Mostly disagree”. Opinions were more mixed on the adequacy of time allocation, with five respondents judging it fully sufficient, four partially sufficient, and four insufficient. Overall satisfaction also revealed some diversity of views: three students indicated “Strongly agree”, five “Mostly agree”, four “Mostly disagree”, and one “Strongly disagree”.

In Turkey, the evaluation questionnaire confirmed a very high level of satisfaction among participants, with average ratings across all items consistently above 4.3 on a 5-point scale. Students particularly appreciated the clarity and communication skills of the trainers (mean = 4.88) and the participatory workshop on local climate actions (mean = 4.88). Group work sessions (mean = 4.88) and activities such as the World Café (mean = 4.76) and Climate Bingo (mean = 4.76) also received very positive evaluations. The venue (mean = 4.59) and the methods and techniques used (mean = 4.59) were rated highly as well. The only aspect with a slightly lower score concerned time allocation (mean = 4.29). Notably, this was the only item where one respondent gave a rating as low as 2, indicating that some students would have appreciated more time for in-depth discussion. Open-ended responses highlighted the practical value of the training, the motivation to become active in Edremit’s climate policies, and suggestions for future improvements, such as increasing hands-on activities or expanding local infrastructure measures (e.g., bike paths).

Taken together, the two evaluations suggest that while both the Italian and Turkish activities were generally well received, certain challenges (particularly the issue of time allocation) emerged in both contexts. At the same time, the consistently high ratings for clarity, trainer competence, and participatory methods confirm the overall effectiveness of the project’s educational approach.

3.3. Communication and Outreach Impact

The project’s communication strategy contributed substantially to its visibility and long-term legacy. A dedicated website (

https://sites.unimi.it/glaciol/index.php/en/home-ttt/, accessed on 15 September 2025) served as a digital archive and resource hub, providing open access to all educational materials, including slides, seminar recordings, and a downloadable e-book. This ensured that the project could reach not only its direct participants but also students, educators, and policy makers beyond the original audience.

The launch of a dedicated Instagram account (

https://www.instagram.com/towntwinningii?igsh=NTd3eGp1bXZvNGti, accessed on 15 September 2025) created opportunities for direct interaction with students on a platform they use daily. Short videos, posts, polls, and story highlights were employed to summarize seminar activities, share climate facts, and showcase behind-the-scenes moments. This informal yet visually engaging channel significantly increased student participation and attracted additional interest from young people outside the immediate project network.

By blending formal education with digital communication tools, the project demonstrated that climate literacy can be fostered not only through academic content but also through the strategic use of social media, thereby amplifying both reach and relevance for younger generations.

4. Discussion

One of the defining strengths of the Youth Participation in Creating Resilient Cities project lies in its multidisciplinary and transnational approach. By combining the expertise of local administrations, academic institutions, and environmental NGOs, the project succeeded in designing an educational program that was not only scientifically rigorous but also civically engaging. This collaborative framework ensured that climate change was addressed simultaneously as a scientific challenge and as a governance issue, allowing students to experience the intersection between knowledge, participation, and policy in practice.

4.1. Bridging Disciplines and Institutions

The project brought together a diverse set of actors, including municipal authorities from Cinisello Balsamo and Edremit, researchers and educators from the University of Milan and Balıkesir University, and environmental practitioners from Legambiente. The municipalities provided political support and access to local infrastructure; the universities contributed scientific rigor; the University of Milan developed the curricula; and Legambiente ensured civic engagement through informal learning methods and student activism. This cross-sector collaboration exposed participants not only to theoretical content but also to real-world applications and local policy-making processes. Students could directly observe how their learning translated into action, empowering them to become advocates and problem-solvers within their communities.

The involvement of the University of Milan was further reinforced by its long-standing scientific research in Turkey’s glaciated regions. Previous expeditions to Mount Ararat (Agri Dagi) had enabled UNIMI researchers to document the unique geomorphology of the area, the catastrophic effects of the 1840 Ahora Gorge event, and the rapid retreat of Ararat’s glaciers over the past three decades [

19]. This body of work provided a solid scientific foundation for the Twinning project and created an opportunity to disseminate glaciological knowledge beyond the academic community. By connecting past scientific evidence with participatory education, the project illustrated how research can be translated into civic awareness and concrete action for climate resilience.

4.2. Cross-Border Cooperation

The partnership between Cinisello Balsamo (Italy) and Edremit (Turkey) is remarkable not only for the geographical distance it spans but also for its symbolic value. Despite differences in language, culture, and climate, the two municipalities found common ground in their concern for the environment and their commitment to engaging young people in sustainability efforts. The project demonstrated that climate change knows no borders, and neither should climate education.

By linking an EU member state (Italy) with a candidate country (Turkey), the project embodied a form of cooperation that extended beyond the EU’s core, fostering mutual understanding and co-learning. This approach aligns with the EU’s vision of inclusive environmental governance and highlights the importance of cross-national exchange in addressing global challenges. The experience of Cinisello Balsamo and Edremit illustrates how municipal partnerships can become laboratories of transnational collaboration, translating shared concerns into joint educational practices and civic action.

4.3. Global Problems, Local Engagement

Climate change is a planetary issue, yet its solutions often take shape at the local level. By positioning youth at the center of municipal dialogue and equipping them with tools to understand both global dynamics and local vulnerabilities (e.g., glacier retreat and biodiversity loss in Italy and Turkey) the project created a bridge between global awareness and local action.

Importantly, the involvement of students from scientific high schools meant that future scientists, engineers, and policymakers were introduced early to sustainability challenges. This exposure not only deepened their understanding of climate change but also helped shape long-term attitudes and professional aspirations, strengthening the prospects for sustained civic and scientific engagement in the years to come.

4.4. Comparative Insights

Several international initiatives (

Table 5) have sought to engage youth in climate education and local action, offering valuable points of comparison with the Twinning project. For example, the Together for Sustainable School project, funded by the EUKI program, involved students and teachers across Lithuania, Cyprus, and Germany in developing school-based sustainability initiatives. Similarly, Estonia’s Youth Climate Assembly provided young people with a voice in shaping national transition policies [

20], while UNESCO’s Sandwatch program has promoted youth-led monitoring of coastal environments worldwide [

21].

Other projects illustrate the diversity of approaches. CLASSY—Climate Smart Sustainability Solutions by the Youth (Turkey–Bulgaria, via eTwinning) and Cool the Earth (USA) highlight how creative, student-centered formats can raise awareness and encourage behavioral change at scale. CLASSY is detailed on the official eTwinning platform, while Cool the Earth has been widely documented, including in public sources such as Wikipedia, for its large-scale reach and measurable impact.

What distinguishes the Twinning project is its unique combination of transnational collaboration, scientific rigor, and digital innovation. Unlike many school-based projects, Twinning actively involved local governments, university researchers, and environmental NGOs in co-designing a comprehensive educational pathway. The integration of interactive tools such as digital carbon footprint calculators, immersive 360° virtual glacier tours, and the establishment of Youth Climate Councils ensured that students gained not only knowledge but also structured opportunities for civic engagement and policy dialogue.

This approach is consistent with broader findings in climate education research: meta-analyses have shown that structured interventions are most effective when they combine interactive, experiential, or gamified methods [

22,

23]. Moreover, the project’s communication strategy (including a bilingual website and an Instagram account) significantly extended its reach among digitally native youth.

By comparing these initiatives, it becomes clear that Twinning offers a compelling model of climate change education: localized yet scalable, technically grounded yet emotionally engaging, and simultaneously academic and action-oriented.

4.5. Recommendations and Replicability

The outcomes of the Twinning project suggest that climate education initiatives targeting young people can be both impactful and replicable, particularly when grounded in transnational collaboration and multidisciplinary partnership. Drawing from the Italy–Turkey experience, several recommendations can be formulated for institutions wishing to adapt this model in different local and cultural contexts.

The first recommendation is to establish a diverse and committed partnership. The involvement of local administrations, academic experts, and environmental NGOs created a robust operational triangle that balanced scientific knowledge, educational expertise, and civic engagement. This configuration ensured that the project went beyond theoretical awareness to generate practical, context-specific action. Municipalities provided political legitimacy and access to youth, universities contributed scientific credibility, and NGOs acted as bridges between institutions and civil society.

Second, climate education should always be locally contextualized. Although climate change is a global phenomenon, its impacts vary across regions. In this project, Italian students explored glacier retreat in the Alps and in Turkey, while Turkish participants addressed both glacier change and issues linked to coastal ecosystems and resource use. Tailoring content to local conditions enhanced relevance and emotional engagement.

A third element concerns the use of interactive and immersive educational tools. Digital carbon footprint calculators and 360° virtual tours of threatened glaciers proved effective in creating emotional resonance and encouraging reflection. Combined with participatory methods such as role-play simulations, workshops, and World Café discussions, these tools fostered critical thinking, teamwork, and civic agency.

Another valuable outcome was the establishment of Youth Climate Councils in both municipalities. These structures enabled students to formulate and present concrete policy proposals to local governments, providing first-hand experience of democratic environmental governance. Ensuring that such councils are supported beyond the project’s duration would help institutionalize youth participation in long-term urban resilience planning.

Finally, all materials developed during the Twinning project (including curricula, workshop guides, and immersive content) have been made publicly available through the project’s online repository. These resources provide a tangible starting point for other regions and institutions wishing to engage youth in building climate-resilient communities.

In summary, the project demonstrates that youth climate engagement can be structured, inclusive, and firmly rooted in local realities, while at the same time embracing a European and global dimension.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

While the findings are encouraging, some limitations should be acknowledged. The study involved relatively small and uneven groups of students, recruited on a voluntary basis, and the intervention was conducted over a short time frame. In addition, no control group was included, item reliability was not formally tested, and the analysis did not extend to longer-term follow-up. These are common constraints in exploratory and practice-oriented projects, but they nonetheless highlight directions for improvement. Future research could build on this pilot by adopting validated instruments, integrating control or comparison groups, and assessing medium-term outcomes such as knowledge retention, civic participation, and policy uptake, thereby strengthening both causal claims and external validity.

5. Conclusions

The Youth Participation in Creating Resilient Cities project has shown that climate change education can be both scientifically rigorous and civically empowering when embedded in a multidisciplinary and participatory framework. By engaging students as active protagonists rather than passive recipients of knowledge, the project fostered not only awareness but also agency, a key element for long-term climate resilience.

Through the collaboration of municipalities, academic institutions, and NGOs, complex scientific knowledge was translated into accessible and emotionally engaging learning experiences. Digital tools, immersive simulations, and participatory methods enabled students to connect global climate dynamics with local challenges such as glacier retreat in Italy and coastal risks in Turkey.

Equally significant was the project’s transnational dimension. The partnership between Cinisello Balsamo and Edremit demonstrated that climate change is a global issue requiring shared responsibility and cross-border learning. The Youth Climate Councils created during the project illustrate how education can translate into tangible civic engagement, offering a replicable model for integrating youth voices into local governance.

Looking ahead, similar initiatives can be adapted and scaled in diverse contexts, provided they are supported institutionally, tailored to local realities, and linked to open educational resources. In this sense, the Twinning project provides a practical roadmap for empowering the next generation of climate leaders.