1. Introduction

In South Africa, under apartheid (1948 to 1994), the term township in everyday usage came to mean a residential development that confined non-White people (Black, Coloured, and Indian individuals) living near or working in White-only communities. The term is still used in official censuses, policy and legislation today. Township tourism (also known as “ghetto, slum, atrocity, ethno, justice or thano” tourism) began in London in the nineteenth century as a way for the wealthy to experience life in impoverished areas [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. There is a growing body of research on township and slum tourism in the global south [

10,

11]. In a post-colonial context, township tourism has become increasingly popular in Namibia and South Africa, where it is marketed with authenticity and interactions and as an educational tool, with culture as the primary draw [

12]. In South Africa, the phrase “township tourism”, refers to the practice of educating visitors about the racist apartheid policy by taking them to townships [

13]. Whilst the ethical and moral justification of township tours have been questioned by some scholars [

14,

15], the economic impacts of the tourism development of townships in South Africa has emerged as an important policy issue [

16].

According to [

10], the rapid expansion, growth and popularity of township tourism across municipalities and towns in South Africa necessitate responsible development and specifically focusing on culture and heritage to ensure an enhanced and unique visitor experience. She further propagates that local authorities should be playing an important role; however, with most municipalities in the country struggling with delivering basic services, it is questionable how much effort they will put into tourism-development initiatives. Metropolitan local governments are, of course, a different story—especially tourism-focused ones such as Cape Town. A review of the literature on township tourism planning in South Africa reveals several challenges [

17,

18]. The nine most significant common challenges are socioeconomic inequality; safety and security; infrastructure, basic amenities and planning; access to capital and resources; local involvement and ownership; perceptions, stereotypes and stigmatization; infrastructure and marketing support; niche markets; and visitor experiences. A brief reflection on the current issues in these nine areas will be discussed next.

Townships in South Africa are often characterized by high levels of poverty, unemployment and inadequate infrastructure [

10,

19]. Developing tourism in impoverished areas requires addressing these socioeconomic disparities to create an environment that can attract tourists and support sustainable tourism development. However, approaches in favour of poverty tourism have yielded only moderate successes to date [

20]. Townships face issues related to crime and safety [

21,

22], thus potentially limiting tourist visits. Tourism-related crime in townships, according to local township residents, can be attributed to drug addiction, unemployment and a lack of basic education [

23,

24]. Numerous studies focus on obstacles to township tourism development [

4,

17,

18,

22,

25,

26,

27]. A precondition “for tourism development is that a destination should have a variety of tourism products available to attract visitors” [

28]. However, many townships lack basic structures, support, infrastructure and amenities required to support tourism, such as reliable transportation, quality accommodation, sanitation facilities and recreational spaces [

19]. Developing or upgrading infrastructure in these areas is necessary to provide a positive visitor experience and attract tourists. The lack of access to financial resources and business development support can hinder the growth of tourism enterprises in townships [

22,

29]. Local entrepreneurs often struggle to access funding, training and mentorship opportunities, which are crucial for starting and sustaining tourism businesses [

19,

30,

31]. In terms of social capital, a study by [

32] has shown the importance of formed connections between White European tourists and Black women township entrepreneurs. In some cases, local communities may feel excluded from the planning and decision-making processes related to township tourism. A lack of community involvement can result in a lack of ownership, potential conflicts and an inability to address the unique needs and aspirations of the community [

31]. Entrepreneurs can influence domestic tourism and the social spaces of the entrepreneurs’ tourist accommodations, allowing tourists to be close to the action in the townships [

33]. Negative stereotypes and stigmatization associated with townships can impact tourism development [

34,

35]. These perceptions can lead to misconceptions about safety, hygiene and the overall visitor experience. Addressing stereotypes and promoting positive narratives about township communities are vital for attracting tourists [

36]. From the inside-out, according to [

37], local residents’ descriptions of their encounters with the tourists “can be seen as helping to ‘polish the wounds of the past’ as they shared a sense of being seen and heard”. Although opinions of general township tourism differ, in the case study of Vilakazi Precinct [

38], reveal that neither residents nor visitors consider the area as a slum, instead the area is seen to be connected to the struggle of heritage. Young people are seen as brokers of a new value system specifically with a focus on heritage in communities. However, there may be apathy of certain community residents that are not interested in tourism development and do not want to take the advantage of the opportunities created by tourism [

39,

40].

Townships often lack the necessary infrastructure for tourism, including tourist information centres, signage and promotional materials [

17]. In addition, effective marketing campaigns, destination branding, brand identity and image and platforms are needed to showcase the unique cultural heritage, history and experiences offered by townships [

41]. Addressing these challenges requires collaboration between government agencies, local communities, private sector, stakeholders and tourism organizations. It is essential to prioritize sustainable development, community involvement and capacity building to ensure the long-term success of township tourism initiatives in South Africa. Two decades ago, ref. [

42] identified the development and constraints of small black-owned accommodation entrepreneurs in the form of bed and breakfast establishments. Since then, this market has evolved with new challenges and opportunities. Airbnb has emerged as a niche market in townships frequented mainly by students, volunteers and academics [

43]. In the accommodation sector the need for understanding online platforms seems to be a struggle faced by such Black-owned enterprises [

44]. However, the recent initiative of an Airbnb African Academy, established in 2017, was introduced to train South African homestay (township accommodation) and guesthouse owners to register and become successful hosts on the Airbnb platform [

45].

Studies have shown that tourists are generally overall satisfied with a township tourism experience [

46]. TripAdvisor has become a useful method of exploring township visitor experiences [

47,

48], and the study by [

35] affirms the “old stereotypes of the global south as a place of global poverty”. A transformative tourism approach is proposed by [

49], in which visitors experience walking individually through the township, where they live as the locals do and where they dine with the locals. In this regard, [

50] emphasizes the importance that township product offerings are effectively communicated to potential visitors.

Langa, Cape Town’s first officially proclaimed Black township, celebrates its centenary in 2023, as it was established after the implementation of the Urban Areas Act of 1923 [

51]. The Act aimed to isolate the Black Africans from urban areas while also serving as a labour reservoir [

52]. A great number of studies focusing on Langa as case study and have been published in recent years, exemplifying the importance of the township as a tourism destination [

33,

35,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Langa means “sun” and is named after the Zulu chief Langalibalele. In 2019, there were an estimated 62,000 residents (21,000 households) living in Langa. The population consists predominantly of young individuals aged between 15 and 34 years [

58]). As is the case in most townships in South Africa, Langa faces socio-economic challenges such as unemployment, crime, housing backlogs and poverty. Almost a quarter of households have no source of income, three quarters have only a school educational qualification and 58% live in formal dwellings with a very high unemployment rate of 43% [

59]. Given the smallness of Langa (1.5 km

2), it does possess a number of tourism-related sites, activities and establishments. Among the key sites are the Langa Heritage/Dompas Museum (see [

57]), the Old Post Office, the historic Beer Hall (not currently utilised as tourism facility), the three town squares (Makana, Mendi and Hamilton Naki), two arts and culture centres (Guga S’Thebe Arts and Culture Centre and Maboneng Township Arts Experience), popular streets (Harleem, King Langabilele and Lerotholi) and restaurants.

The Tourism Development Department of the City of Cape Town (CoCT) has identified Langa as a prime township tourism destination and a number of draft tourism development strategy documents have been prepared since 2016 (for a listing of these see [

59]). However, key information regarding how residents and stakeholders (NGO members, entrepreneurs, traditional and community leaders and Langa residents working in the tourism industry) feel about tourism, their opinions on the potential thereof for Langa and the concerns for its growth was needed to inform the tourism planning process.

2. Materials and Methods

Sub-Council 15 of the City of Cape Town (CoCT) initiated a project in Langa aimed at conducting interviews with local community members to gauge their perceptions of tourism. The interviews were conducted by workers from the Expanded Public Works Programme. The data collected from these interviews were intended to be utilized by the CoCT’s Department of Tourism Development for the preparation of various tourism-related development projects and initiatives.

A qualitative approach was adopted for this study. Two participant groups were identified: residents and stakeholders. The participants were purposively selected. A total of 53 in-depth interviews were conducted. Geographically, Langa comprises six distinct housing typologies (number of in-depth interviews in brackets): flats (18), hostels (7), informal settlement (5), middle-income (7), high-income (7) and the historic area of the township (9). All interviews were transcribed, and when conducted in another language, they were translated. A survey question sheet was used for all interviews, focusing on aspects such as the respondents’ age, background, duration of living in Langa, their community’s spirit, the state of infrastructure in the township and their general understanding of and appreciation for tourism, their perception of Langa as a suitable destination for tourism, its ability to attract tourists, their involvement in community-related matters, especially those related to tourism and the issue of safety in Langa, particularly in the context of tourism.

For the second participant group, interviews were conducted with interviewees from two NGOs operating in Langa, three tour operators and local entrepreneurs (seven) and with four community leaders.

After transcription, the transcripts underwent a cleaning process to remove unnecessary wording. These cleaned transcripts were then input into Word Cloud Online, generating a thematic word cloud. This word cloud served as a guide for analysing the data based on the main themes that emerged. Additionally, specific direct quotations were selected to highlight particular aspects of the data.

3. Results

Twenty-six female and twenty-seven male residents residing in Langa participated in the survey. The average age of the respondents was 41 years, ranging from the youngest at 20 years old to the oldest at 91 years old. On average, participants had resided in Langa for 18 years, with the longest residency being 91 years.

3.1. Resident Viewpoints on Tourism Development

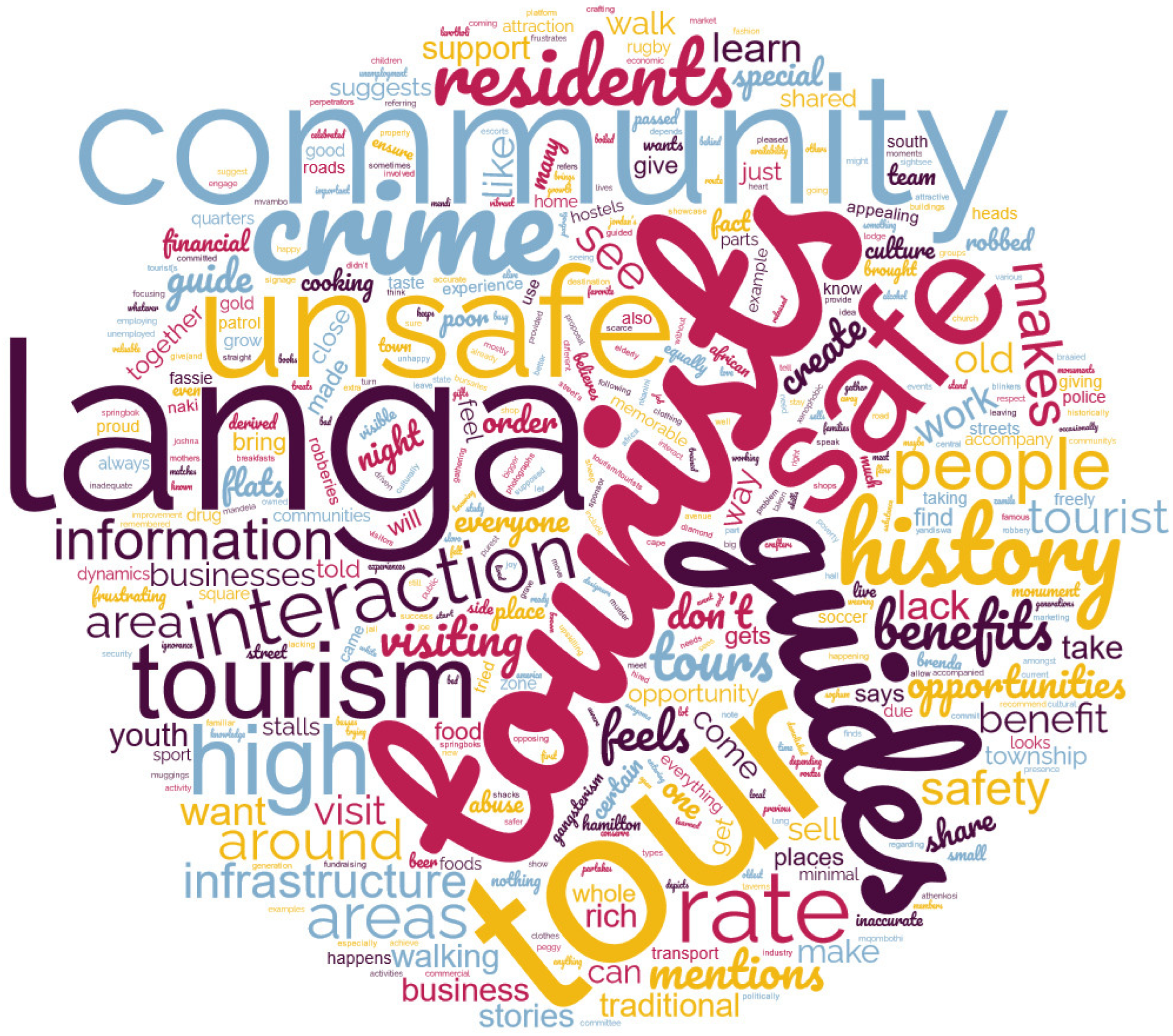

Township tourism provides tourists with a distinctive opportunity to directly engage with local communities, fostering cultural exchange, promoting mutual understanding and creating profound and meaningful experiences. The data analysis encompasses a variety of perspectives from residents of Langa concerning tourism in the area. These viewpoints are categorized into four main themes: crime trends in Langa, opinions on tourist safety, Ubuntu and community spirit and Langa’s unique history and tourist experience. The word cloud (

Figure 1) highlights the most prominent opinions in the following order of importance: tourism-related elements (tourists, tour guides, tours and tourism), Langa (including its history and community) and the issue of crime and safety. This emphasizes the significance of these four key themes. Considering that safety and crime concerns are intertwined with the other themes, the discussion on this topic will be integrated.

3.1.1. Theme 1: Crime Trends in Langa

The issue of crime and safety and security emerged as the main central focus point in all the in-depth interviews with participants. Concerned activists, criminologists and residents from Langa are worried about the increasing crime trends, saying it might soon become a hot spot like Nyanga if the police, province and city do not implement policing strategies [

60]. The overall murder rate in Langa decreased by 17% between 2010 and 2015. However, by 2016, Langa was reported to be the most notorious murder hotspot out of the nine areas within the Cape Town cluster. Langa’s murder rate contributed to 55% of murders in Cape Town [

61]. The power of tourism social media platforms, such as TripAdvisor and others, are well known [

62,

63,

64]. Langa features, among others, in one such TripAdvisor post [

65] about which areas of Cape Town visitors should stay away from (

https://www.tripadvisor.co.za/ShowTopic-g312659-i9466-k2671771, accessed on 15 August 2023). Multiple attempts to address the crime situation in Langa have been seen over the past decade. In 2015, for example, during a community workshop, neighbourhood watch groups and other community safety groups emphasized the need for better policing resources and training [

61]. According to the participants, various attempts to address the crime situation, such as community workshops and calls for better policing resources and training, have been made in the past.

It is evident from the survey that Langa is only safe in certain areas. Respondent NO (40, female, resident of Langa since age of 19) suggests that the main cause of the crime in Zone 1 is due to unemployment and drug abuse. She mentions that the community does not get involved when the different gangs fight; the community always calls the police, asking them to intervene. However, she feels that they do not help adequately: “They [the police] are not helpful at all because when we call [the police], they say there are no vehicles [available], we must wait while children are dying”. Respondent NO then stated that a neighbourhood watch would help much more than the police because “we as a community must work together in fixing our area and not depend on the South African Police Services”. She, however, feels strongly that “the tourist[s] in Langa must be safe”. Suggestions for the safety of tourists include street committees and a neighbourhood watch. Respondent Z (51, male, lived in Langa all his life) suggests that safety could be brought about by upskilling the community. Moreover, safety could be enhanced by traveling in groups. According to respondent MP (60, male, resident of Langa for 20 years), tourists usually travel in groups with the tour guide with no private security, but he still believes that the safety of tourists cannot be guaranteed. Notwithstanding, the community would look out for them to try to keep them safe. He believes that having committees such as a neighbourhood watch could play a role in their safety, especially if the neighbourhood watch works with SAPS.

According to respondent G (male, 40) who has been living in Langa since his birth 40 years ago, tourists are not safe due to the high crime rate, especially murder, robberies and drug abuse. The reason that tourists are not safe is because tour guides do not want to collaborate with the community. Despite the presence of tourist accommodation establishments, respondent N (male, 44, lived in Langa all his life) cautions that although there are “Bed n Breakfasts’” in Langa, he does not recommend that tourists to come to Langa at night as it is unsafe for them then.

Respondent A (30, female, resident of Langa for 15 years) does not feel that Langa is safe, particularly at night, because she cannot leave her home at night even to go to the shop. She does not feel that only a neighbourhood watch would help with the safety but that Langa needs police to patrol every day. She is trained to be part of the neighbourhood watch in order to help with safety in Langa, but the crime does not make it safe for tourists to visit because they would be risking their lives.

3.1.2. Theme 2: Opinions on Tourist Safety

Opinions of Langa residents were mixed on safety and security for tourists. On the one hand there is the opinion that “Langa is not safe” (respondent Alo), yet on the other hand it is argued that tourists are safe (depending on certain situations). Certain factors contribute to safety concerns, including crime rates, tour guide behaviour and the time of day. Participant suggestions for enhancing tourist safety include the introduction of street committees, neighbourhood watch programs and community involvement.

Respondent J (32, female, resident since 2010) thinks that the tour guides are not doing their job properly and feels that they should explain to tourists about safety risks and tell them what they should have in their possession when visiting. She also feels that they are intentionally not going to all the areas of Langa because the tour routes are always the same. She also feels that the tour guides are greedy because a single tour guide would take many tourists on a tour and would not ask other tour guides who have not received any business to assist. Respondent J believes that the street committees should be involved in deciding the exact tour guide routes, and by doing so, they can provide safety for the tourists. She mentions that safety is dependent on the time of day, as it is much safer during the day than it is at night because one could get mugged and stabbed at night. A similar sentiment was expressed by respondent NQ (50, male, lived in Langa all his life). Due to tour guides taking the tourists to places where they have heard it is safe, he also feels that only the tour guides benefit from tourism. He says that the tour guides need to be better educated on the history and dynamics of Langa; therefore, residents of Langa should be the tour guides because they understand the roots and routes of Langa.

On the other hand, other residents are of the opinion that tourists are safe in Langa. Residents view the fact that tourist walking around freely means that they are safe, such as respondent VO (40, female, length of residency in Langa unclear) and others. Respondent S (26, female, resident since birth) feels that “tourists are only safe when accompanied by a tour guide”. Although the crime rate is high in Zone 1, with issues such as gangsterism, robberies and drug abuse, respondent MA (33, female, resident since birth) believes that Langa is safe for tourists. Respondent MA also think that Langa residents “respect people from other areas because tourists walk up and down here [and] nothing happens to them”. According to respondent AK (male, 27, four and a half years) Langa is safer than any other township, but this is due to everyone in Langa knowing each other. However, he feels that tourists are only safe in the areas of Langa where their tour guides are known. He mentions that extra security is occasionally hired to follow behind the tourists. However, he does believe that tourists are no longer being robbed because the thieves are chased out of the community if they attack tourists. Respondent Y (38, female, length of residency in Langa unclear) says that Langa makes her proud due to the fact that their communities are not xenophobic and treat tourists very well. Communal spirit features strongly in safeguarding visitors to the township.

3.1.3. Theme 3: Ubuntu and Community Spirit

The data highlights the significance of Ubuntu, a Southern African philosophy and term that represents a fundamental African worldview and ethic of interconnectedness, communalism and shared humanity. In the context of Langa, a community where residents value interconnectedness and shared humanity, residents see Langa as an embodiment of Ubuntu, where everyone looks out for one another and practices mutual support despite having limited resources. A Langa middle-class resident (respondent MC, 28, female) referred to Langa as a “Skomline” (area of the people) because everyone looks out for one another and believes that everyone wants to practice Ubuntu. According to respondent YZ (48, male), Ubuntu is “the ability to share with those who have nothing, despite having very little yourself”. Another middle-class respondent, respondent NQ (39, female), defines Ubuntu as the ability to help one another and lend a helping hand to help someone in need while empathizing with them.

The data suggest that promoting Ubuntu in tourism development can involve encouraging communal living through participation in tourism activities. The idea of Ubuntu speaks directly to the issue of safety. Respondent TE (50, male, lived in Langa all his life) underscores the role of the community in ensuring visitor safety by actively addressing crime issues. Respondent TE says that the community keeps the visitors safe because the residents make sure they do something about a crime.

3.1.4. Theme 4: Langa’s Unique History and Tourist Experience

The significance of Langa’s history and the enthusiasm of some residents about preserving it has been noted in the interviews. One of the upper-class residents, respondent TE (42, male), has lived there his entire life and believes that Langa is unique and this excites him because of what Langa already has and how they use what they have. “Here in Langa we do not take things for granted, everything that we have, we conserve everything we have, such as the buildings that we have for our history and the history itself, which you can find in books and [be told stories by] elderly people who are still alive”. This respondent believes that “the memories that we have, apha kwaLanga (here in Langa) are everywhere, especially in the Old Langa where, wherever you are standing or [whichever direction you are] facing, [anything you] see, you know some history about it”. This demonstrates that Langa is rich in history. Criticisms of tour guides for not providing accurate information about Langa’s history have also been raised. In addition, he believes that the history that is shared with the tourists are not the stories that should be told. “I do see tourists [walking] up and down the streets [but] they are scarce on this side, but they are not told the right stories about Langa because the tour guides themselves make them [the tourists] wear blinkers and focusing on certain areas of Langa which is giving them [the] wrong information”. He emphasized the importance of gathering information from residents of both “Old Langa” and “New Langa” to present a more comprehensive tourist experience.

3.2. Stakeholder Opinions: Tour Guides, Community Leaders, Entrepreneurs and Members of NGOs

The challenges faced by township tourism encompass a wide spectrum, spanning from the overhaul of the tourism industry and conflicting policy intentions and intervention strategies in entrepreneurship to historical infrastructural obstacles, perceptions surrounding the overall township economy and a backdrop shaped by the adverse political repercussions of the apartheid system [

18]. In a similar vein as for the residents, key stakeholders were questioned about tourism development challenges in Langa in general.

Tour guides are available to offer their services to tourists for walking and driving tours around Langa, which creates a positive externality in the host community while improving safety. Tour guides are either independent operators or belong to a company. These tour guides use word of mouth, brochures, websites, social media platforms and tourism associations to market their tour operations. To function efficiently, tour guides undergo tour guide training and workshops using Langa tourism office space and equipment to enhance community awareness for township tours (City of Cape Town, 2016).

Leaders in the community are similarly of the opinion that Langa is not really safe for tourists. One respondent (respondent L, 49, male) reported that he was not proud of Langa due to poor infrastructure and a high crime rate. As a result, he believes that tourists are not safe in the area. He also reported that there is not much land for small business development. He further stated that the community does not benefit equally from tourist activity, as tourists do not visit all the stalls. He suggests that the government should become involved and further emphasized that tourists should be exposed to the rich history of Langa. According to another community leader (respondent L2, female, 53, lived in Langa for 10 years), different housing “groups” (or “sections”) cause division in the community, but despite this, she continues to contribute to the area and offer help in the community. She mentions that the infrastructure in Langa is in a poor state and there is a lack of involvement from the community in tourism. According to the respondent, this is due to lack of engagement between tourists and the residents of Langa. She blames this lack of engagement on the tour guides, who create a negative externality in the host community while not including residents in the economic impacts of tourism: “Tourism is practiced incorrectly” and “…the community does not get notified when tourists are in the area, she wishes that they were informed”. She reiterates that the old flats are rich in culture and tourists spend lots of time looking at art murals due to the rich history of Langa. She suggests a new approach as to how tourism should be practiced in Langa. In agreement with the respondents above, a further respondent agrees that there is division in the community. He (respondent MV, 52, male, lived in Langa since 1983) also blames tour guides for the lack of interaction between tourists and residents as “tour guides do not give adequate information”. He further reported frustration towards tour guides based on the routes they take (they are not taken to important landmarks, and they are taken on the same route each time). The respondent provided two main suggestions to improve tourism in the area. One, to increase tourist and resident interaction to share more accurate stories and information about Langa. Two, to hire older tour guides who know the history of Langa as the younger guides do not have in-depth knowledge of Langa. Another community leader (respondent OM, 41, female, resident since birth) expressed similar sentiments and expressed frustration that the community does not benefit from tourism as tour guides do not conduct tours in “proper areas”, tour guides are not from Langa and tourists are not safe in the area.

Local entrepreneurs in Langa have established many small businesses such as art galleries, restaurants, tour guide businesses, artists and coffee shops. One local entrepreneur who owns a music academy believes that Langa is no longer safe for tourists to visit as crime has increased in the area: “…many tour guides use the same routes for their tours and believes that this is due to the fact that they are from the specific area and would feel comfortable going into that area. Many go to old Langa... due to their comfortability” and “...when tourists arrive in Langa they are advised to leave their bags behind which sometimes causes the tourists to not support the businesses in Langa as he feels that tourists should support businesses in the areas that they tour to experience” (Victor, 54, male). It could be said that tour guides take familiar routes to ensure the safety of the tourists; however, tour guides do not take routes with rich history. Thus, one respondent suggested that tourists should visit more historically rich parts of Langa and that involvement between residents and tourists should be increased: “...Langa would have to use their tradition to their advantage and turn it into something more professional which would attract tourists even more to Langa”.

When questioned about factors that would enhance tourism development in Langa, one community-based tourism vendor, respondent SG (51, female) stated that “improved marketing, access to funding, the development of tourist attractions and lower levels of crime are the main catalysts for local economic development”. Although the majority of the vendors believed that tourism development could raise the profile of Langa as a whole and stimulate other business activities, they also believed “that Langa is not safe for tourists because they can be seen as targets by opportunistic thieves and that the community has a perception that tourists are rich because they assist the community”. They were also concerned that future tourism opportunities would be snatched up by large corporations, and they emphasized the importance of providing more opportunities to local entrepreneurs, tour operators and guides; this is consistent with the literature [

40,

66]. Another community-based tourism vendor (Magwaca, male, 49) stated that the festivals that used to take place in Langa when he was growing up, such as the markets of different second-hand clothing and crafters and the celebration of

Ntsika (a parade of traditional dancing alongside chiefs from different cultures such as Xhosa, Sotho and Zulu) have since been discontinued due to financial issues. He claimed that the Langa Tourism Association was formed to bring together everyone involved in the tourism in Langa but instead it excluded people from the tourism industry due to differences in opinion. He claimed that the Langa Tourism Forum served the same purpose, but people were excluded from the association. The exclusions occurred in the same way, where members did not notify everyone involved about matters and even inducted people who were not from the tourism industry, as chairpersons, which caused a dysfunction in the association.

Magwaca (who also doubles as a resident freelance tour guide) further reported that it is not always safe for him, but this depended on which roads he took in Langa. He avoided dangerous areas like Joe Slovo because he does not know anyone there, and he stated that he would not take his clients there. He mentions that a neighbourhood watch used to be visible but that they are no longer present, and as a result, the men of Langa decided to start a safety patrol in the community; he mentioned that if a neighbourhood watch was visible, they would be very effective. He states that he hires locals from the area to keep himself and his clients safe. Another resident/tour guide believes that Langa is unsafe due to strained relationship between the community and tourism agencies. He believes that in order for tourists to be safe in Langa, Langa requires tour guides who are Langa residents, as well as a partnership between a united community and the tour guides. Despite the uncertainty, respondent LEK (28, female) recalls the Springboks (South Africa’s rugby team) visiting Langa, an event that will be remembered in the community.

Two individuals from NGOs were interviewed. Both respondents reported that Langa is not safe for tourists unless they are accompanied by a tour guide. Again, one respondent (male, 29) reiterated that tourists do spend much time in areas that are rich in history and important to the culture of Langa and they only pass through the other areas. Thus, it was suggested that increased interaction between tourists and residents would benefit residents. The other respondent (female, resident in Langa since birth) feels the same and suggested that they require some support from tourism organizations.

There are great prospects for South African township tourism development. South African townships are rich in cultural heritage, offering visitors unique experiences, traditional music, dance, arts and crafts and local cuisine. Many townships played a crucial role during the apartheid era, and tourists are interested in exploring the historical sites and stories associated with the struggle for freedom and social justice. Tourism in townships has the potential to stimulate economic growth, create job opportunities and contribute to the overall development of these communities. However, “a caution about tourism as a driver for development must be raised. It is true that some township areas may have attractions that will encourage local and international tourists. It is possible that some investments into supportive infrastructure will help in making tourist money ‘stick’ in the townships. Too often though we see supply side interventions being built that cannot ever succeed” [

67].

4. Discussion of Findings

This study on residents and stakeholders’ opinions reveals a range of opinions from Langa residents regarding township tourism (particularly regarding the safety of tourists). From the findings, concerns about safety were mixed. On one hand, some residents express concerns about crime rates, particularly at night, attributing it to high levels of murder, robberies, and drug abuse. These residents suggest that tour guides and community collaboration are essential for ensuring tourist safety. On the other hand, some residents believe that tourists are generally safe, especially when accompanied by a tour guide or walking in certain well-known areas (see

Figure 2; group of students from the University of Iceland on a Langa township tour). This discrepancy in perceptions reflects the complex nature of safety in Langa.

Several factors contribute to the varying opinions on tourist safety [

23,

68]. The historical context of crime rates and the presence of criminal activities in specific zones within Langa play a significant role. Unemployment and drug abuse have been identified as key contributors to crime, particularly in Zone 1. The effectiveness of law enforcement, community engagement and collaboration with tour guides also shape residents’ perceptions of safety [

24]. Residents who advocate for community involvement, such as neighbourhood watch groups and street committees, emphasize the role of local empowerment in enhancing safety. The idea of Ubuntu as a sense of communal responsibility and support and emerges as a driving force behind these efforts, which also resonates with [

69]. Engaging residents, especially those from “Old Langa” with a deeper historical understanding, could provide tourists with a more authentic and informative experience, potentially dispelling misconceptions and fostering a sense of trust and safety. The dynamic between tourists and the community plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions of safety. The belief that tourists are safe when accompanied by tour guides who understand the area suggests the potential for cultural tourism to positively impact safety perceptions. However, concerns about tour guides’ knowledge and routes indicate room for improvement. Promoting cultural understanding, emphasizing local history and involving the community in tour guide roles could contribute to safer and more informed tourist experiences. To address safety concerns and promote a positive tourist experience, a multi-faceted approach is necessary. Strengthening collaboration between law enforcement, community safety groups and tour guides is essential. Upskilling the community, fostering communal living through Ubuntu principles and involving residents in guiding tours could enhance safety and provide tourists with a richer understanding of Langa’s history and culture.

Turning to the viewpoints of various stakeholders in Langa, the difficulties facing township tourism are numerous and varied. These challenges include extensive reforms required within the broader tourism industry, conflicting policy directives, historical infrastructural impediments, perceptions of the township economy and the lingering political repercussions of apartheid. It is evident that these multifaceted issues, which are also present in Langa, collectively contribute to the impediments faced by township tourism. However, developing community ties with the help of stakeholder consultation could be a good place to start in order to overcome these challenges.

In addition, a significant aspect of understanding township tourism challenges lies in examining the perspectives of key stakeholders. Residents and community leaders within Langa express concerns about safety, poor infrastructure and a lack of engagement between tourists and the local community. Their frustration with tour guides and tour routes highlights the necessity for more accurate historical representation and more inclusive practices. Local entrepreneurs, while recognizing the potential of tourism, are hampered by crime perceptions, limited tourist exposure to local businesses and exclusion from decision-making processes. These perspectives further emphasize the need for a comprehensive strategy to deal with the challenges in township tourism. The prevailing theme of safety resonates across stakeholder viewpoints. Concerns regarding crime and safety influence tourists’ experiences and perceptions of townships [

24]. The idea that tourists feel safer when accompanied by tour guides suggests that tour guides play a critical role in mitigating potential risks. However, the reliance on familiar routes can result in a lack of exposure to historically significant sites, undermining an authentic cultural experience such as the cooking of sheep heads.

Encouraging greater interaction between tourists and residents, along with in-depth knowledge-sharing, emerges as a potential solution to enhance safety and foster meaningful engagement. The potential of township tourism to stimulate economic growth and create job opportunities is widely acknowledged. However, this potential can only be harnessed through strategic efforts that involve the local community and ensure the equitable distribution of benefits. The exclusion of local entrepreneurs and community members from decision-making processes, as evidenced by the experiences shared by community leaders and vendors, hampers the realization of these economic benefits. Other authors [

70,

71] believe that empowering residents through participation in tourism-related initiatives, supporting small businesses and facilitating collaboration between stakeholders could catalyse positive economic developments. Achieving sustainable township tourism requires the integration of and balance between economic growth, cultural preservation and community engagement. Rather than pursuing supply-side interventions that may not align with the unique dynamics of townships, a holistic approach should be adopted. This approach entails infrastructural improvements that support local businesses, facilitate safe interactions between tourists and residents and foster an environment conducive to cultural exploration [

25]. Therefore, encouraging responsible tourism practices that prioritize authentic experiences and the empowerment of local communities is paramount [

2,

13,

72,

73].

Prioritizing multifaceted challenges, balancing the interests of different stakeholders and addressing these issues effectively requires a systematic and strategic approach. As a starting point, this study lays the foundation for identifying certain challenges for tourism development through the stakeholder engagement. Future steps must prioritize these challenges, based on their urgency, potential impact and the feasibility of addressing them. The input of various stakeholders needs to be considered in this process to ensure a holistic perspective, which would then ideally be crafted into a holistic strategy, outlining specific goals, objectives and action plans for each challenge. Encouraging collaboration among stakeholders and promoting partnerships between the private sector, local communities and government agencies to leverage resources and expertise is crucial. So too is ensuring that the local community is actively involved in decision-making processes and benefits from tourism development. Empowering the local community by providing opportunities for training, job creation and entrepreneurship must be part of such a holistic strategy.

5. Conclusions

We investigated residents’ and stakeholders’ perceptions of Langa township tourism development in this study. Given that tourism stands as a burgeoning industry, its offerings are likely to receive both positive and negative feedback from residents and stakeholders.

This study found that the challenges faced by township tourism in Langa underscore the intricate interplay of historical, socio-economic and cultural factors. Overcoming these challenges necessitates a collaborative effort involving residents, entrepreneurs, community leaders and government bodies. By reimagining the role of tour guides, promoting community engagement, supporting local businesses and facilitating sustainable development, township tourism has the potential to not only offer visitors unique cultural experiences but also uplift the communities that host them. The findings from this study present an opportunity for residents, stakeholders and the government to provide suggestions to improve township tourism in Langa. This can help us to better understand the symbiotic relationship between tourism and localities and how these localities interact with the tourism industry to promote township tourism development.

Nonetheless, in future research, it is imperative to acknowledge the distinct contextual and historical dimensions that envelop the geographies of township tourism development and planning across diverse research settings. These historical and contextual factors wield influence over the contemporary and future dynamics, as well as power dynamics, of township tourism within specific locales. This may be useful for the National Department of Tourism in developing policies and strategies for the long-term viability of township tourism in a nuanced and context-sensitive manner, ensuring that tourism can truly serve as a catalyst for positive change within townships. Furthermore, the matter of safety can be linked to consumer behaviour and the various demographics of tourists.

In summary, addressing multifaceted challenges in township tourism requires a collaborative, flexible and holistic approach. Prioritizing challenges and balancing stakeholder interests are crucial components of this process. By involving all relevant parties and maintaining a long-term perspective, it is possible to work towards sustainable and inclusive tourism development in townships with limited resources.