Stroke Frequency Effects on Coordination and Performance in Elite Kayakers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- increasing paddle stroke frequency would lead to higher mechanical work and energy expenditure;

- (2)

- stroke variability would decrease as stroke frequency increases, reflecting greater technical stability; and

- (3)

- an intermediate frequency (around 80 strokes·min−1) would represent an optimal balance between efficiency, coordination, and performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

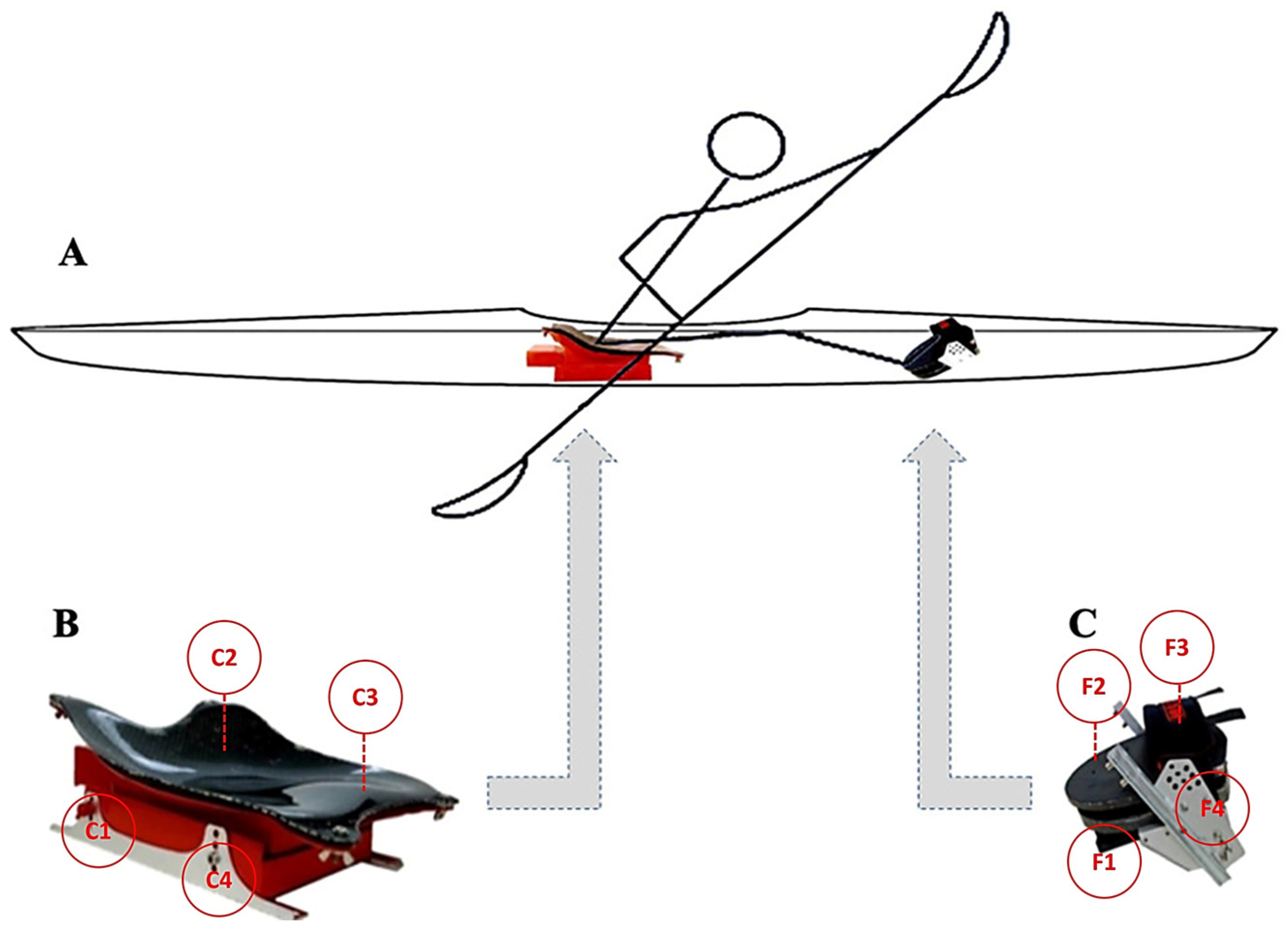

2.2. Experimental Setting

2.3. Measurement

2.4. Phase Coordination Index Calculation

2.5. Signal Conditioning, Filtering, and Stroke-Cycle Segmentation

2.6. Mechanical Work and Transmission Efficiency

2.7. Paddle Factor

2.8. Time

2.8.1. Statistical Analysis

2.8.2. LME Model Specifications

2.8.3. Preliminary Checks

2.8.4. Multiplicity Control

3. Results

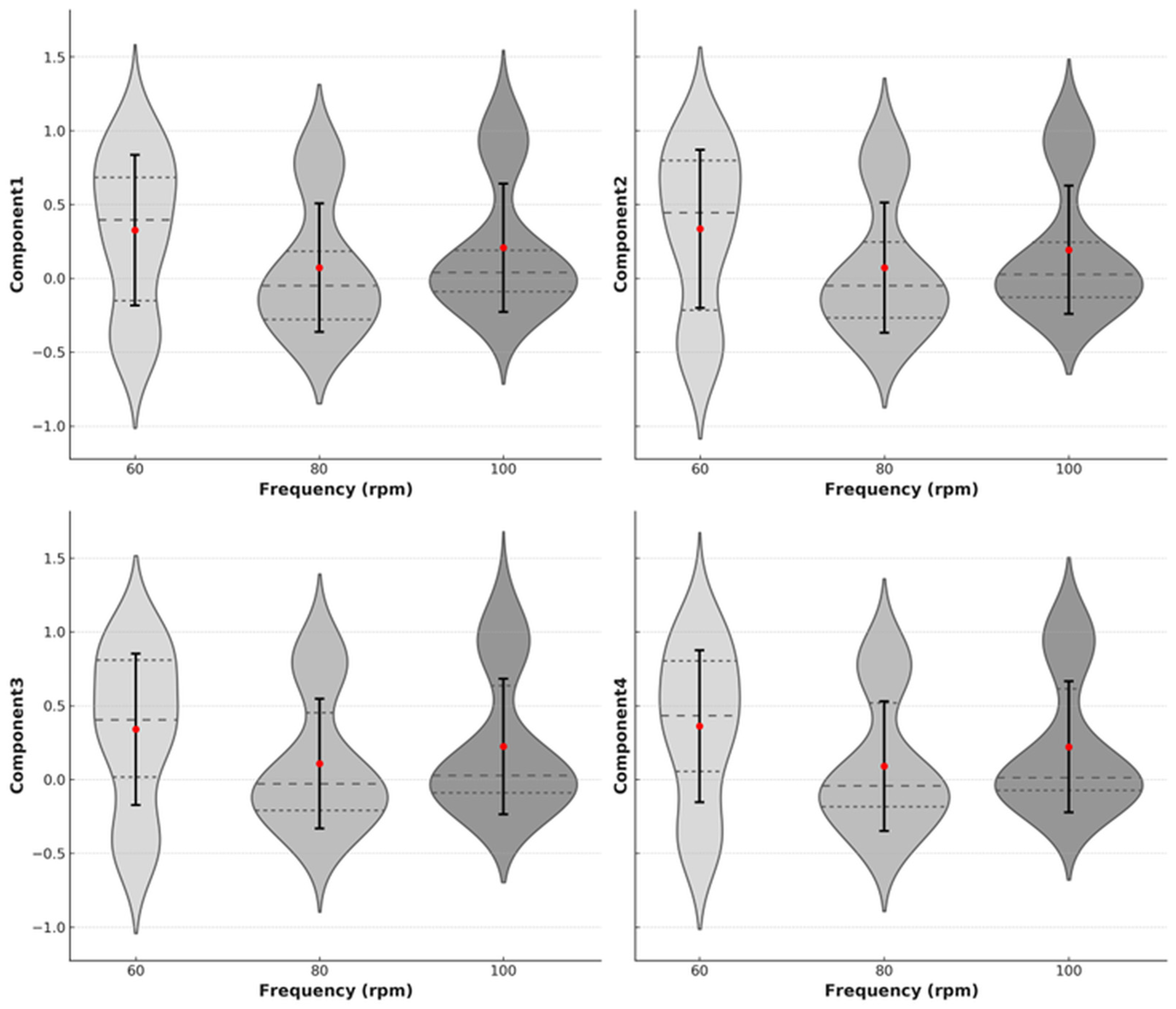

3.1. Commentary on Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- The shape of the violin represents the density of values; a wider shape indicates a higher concentration, whereas a narrower shape signifies a more uniform distribution.

- Error bars, positioned at the center of the violin, indicate the mean (central point) and standard deviation (bar length). Shorter bars reflect greater consistency in the data, while longer bars indicate higher variability.

3.2. Summary of Observations

- Component 1: At lower cadences (60 strokes·min−1), variability is greater, and the mean is lower. Higher cadences (80, 100 strokes·min−1) show greater stability, suggesting that this component is related to efficiency or technical stability.

- Component 2: The distribution is more concentrated, and the mean is higher at 80 strokes·min−1, indicating that, in this acute trial, this intermediate cadence was associated with relatively greater power application and technical consistency when compared with 60 and 100 strokes·min−1.

- Component 3: At 80 strokes·min−1, values are more uniform and the mean is higher, signaling better technical control. At 60 strokes·min−1, greater variability is observed, indicating difficulties in maintaining a smooth motion.

- Component 4: At 60 strokes·min−1, the distribution is more concentrated, suggesting greater control at lower cadences. However, at 100 strokes·min−1, the wider error bar indicates greater instability in force application.

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.3.1. PCI

3.3.2. HRWEEK

3.3.3. TE

3.3.4. Kinematic Parameters Across Paddle Frequencies

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpreting the “Negative Mechanical Energy–Experience” Association

4.2. Novelty of PCI Applications in Canoeing

4.3. Potential Fatigue at the Highest Cadence (100 Strokes·min−1)

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

4.5. Practical Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garnier, Y.M.; Hilt, P.M.; Sirandre, C.; Ballay, Y.; Lepers, R.; Paizis, C. Quantifying Paddling Kinematics through Muscle Activation and Whole Body Coordination during Maximal Sprints of Different Durations on a Kayak Ergometer: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, B.C. What Defines Different Modes of Snake Locomotion? Integr. Comp. Biol. 2020, 60, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.; Spittle, S.; Spittle, M. Considering the Need for Movement Variability in Motor Imagery Training: Implications for Sport and Rehabilitation. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1178632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowin, J.; Nimphius, S.; Fell, J.; Culhane, P.; Schmidt, M. A Proposed Framework to Describe Movement Variability within Sporting Tasks: A Scoping Review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, D.; Simms, C.K. Reliability and Measurement Error of Multi-Segment Trunk Kinematics and Kinetics during Cerebral Palsy Gait. Med. Eng. Phys. 2020, 75, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, R.; Wheat, J.; Robins, M. Is Movement Variability Important for Sports Biomechanists? Sports Biomech. 2007, 6, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, F.J.; Caballero, C.; Barbado, D. Editorial: The Role of Movement Variability in Motor Control and Learning, Analysis Methods and Practical Applications. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1260878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, L.; Di Capua, R.; Arnone, B.; Borrelli, M.; Coppola, R.; Esposito, F.; Padulo, J. Shoes and Insoles: The Influence on Motor Tasks Related to Walking Gait Variability and Stability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, B.T.; Schindler-Ivens, S. Symmetry Is Associated with Interlimb Coordination During Walking and Pedaling After Stroke. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2022, 46, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Kim, C.O.; Kim, K.J.; Jeon, J.; Chang, H.; Kim, E.S.; Park, H. Quantitative Analysis of the Bilateral Coordination and Gait Asymmetry Using Inertial Measurement Unit-Based Gait Analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwood-Brown, A.J.; Brown, H.L.; Oakley, B.; Felton, P.J. Determinants of Boat Velocity during a 200 m Race in Elite Paralympic Sprint Kayakers. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2021, 21, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeling, J.M.; Smiešková, S.; Pratt, J.S.; Vajda, M.; Busta, J. Asymmetries in Paddle Force Influence Choice of Stroke Type for Canoe Slalom Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1227871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vando, S.; Laffaye, G.; Masala, D.; Falese, L.; Padulo, J. Reliability of the Wii Balance Board in Kayak. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015, 5, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gam, S.; Klitgaard, K.K.; Funch, A.B.; Sloth, M.E.; Holt, J.W.; Molbech, J.L.; Hansen, E.A. Optimal and Freely Chosen Paddling Rate during Moderate Kayak Ergometry. Biol. Sport 2022, 39, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovo-Santos, M.; Zacca, R.; Fernandes, R.J.; Vilas-Boas, J.P. The Impact of a Single Surfing Paddling Cycle on Fatigue and Energy Cost. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbett, T.J. The Training-Injury Prevention Paradox: Should Athletes Be Training Smarter and Harder? Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring Training Load to Understand Fatigue in Athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnie, M.J.; Astridge, D.; Watts, S.P.; Goods, P.S.R.; Rice, A.J.; Peeling, P. Quantifying On-Water Performance in Rowing: A Perspective on Current Challenges and Future Directions. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, H.H.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, Y.C.; Hao, Z.D. Paddle Stroke Analysis for Kayakers Using Wearable Technologies. Sensors 2021, 21, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, V.; Gatta, G.; Romagnoli, C.; Boatto, P.; Lanotte, N.; Annino, G. A Pilot Study on the E-Kayak System: A Wireless DAQ Suited for Performance Analysis in Flatwater Sprint Kayaks. Sensors 2020, 20, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. The Progress of Biomechanical Researches in Kayaking. Yangtze Med. 2017, 1, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Padulo, J.; Kasmi, S.; Ben Othmen, A.; Chatra, M.; Behm, D.G. Unilateral Static and Dynamic Hamstrings Stretching Increases Contralateral Hip Flexion Range of Motion. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2017, 37, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, H.L.; Ting, L.H.; Bingham, J.T. Accuracy of Force and Center of Pressure Measures of the Wii Balance Board. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J.M.; Mancini, M.; Peterka, R.J.; Hayes, T.L.; Horak, F.B. Validating and Calibrating the Nintendo Wii Balance Board to Derive Reliable Center of Pressure Measures. Sensors 2014, 14, 18244–18267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.A.; Mentiplay, B.F.; Pua, Y.H.; Bower, K.J. Reliability and Validity of the Wii Balance Board for Assessment of Standing Balance: A Systematic Review. Gait Posture 2018, 61, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnik, M.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. A New Measure for Quantifying the Bilateral Coordination of Human Gait: Effects of Aging and Parkinson’s Disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 181, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, R.O.; Herzog, W.; Nigg, B.M. Use of Force Platform Variables to Quantify the Effects of Chiropractic Manipulation on Gait Symmetry. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1987, 10, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, B.B.; Machado, L.; Ramos, N.V.; Conceição, F.A.V.; Sanders, R.H.; Vaz, M.A.P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Pendergast, D.R. Effect of Wetted Surface Area on Friction, Pressure, Wave and Total Drag of a Kayak. Sports Biomech. 2018, 17, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Coertjens, M. Locomotion as a Powerful Model to Study Integrative Physiology: Efficiency, Economy, and Power Relationship. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Modeling with Crossed Random Effects for Subjects and Items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M.; Walker, S.C. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Christensen, R.; Brockhoff, P. Different Tests on Lmer Objects (of the Lme4 Package): Introducing the LmerTest Package. In Proceedings of the R User Conference, Albacete, Spain, 10–12 July 2013; pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Padulo, J.; Rampichini, S.; Borrelli, M.; Buono, D.M.; Doria, C.; Esposito, F. Gait Variability at Different Walking Speeds. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, P.W.; Osborne, A.; Stannard, S.R. Mechanical Work and Physiological Responses to Simulated Flat Water Slalom Kayaking. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Jin, N.; Li, Y. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Workload and Injury Risk of Professional Male Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furrer, R.; Hawley, J.A.; Handschin, C. Themolecular Athlete: Exercise Physiology Frommechanisms to Medals. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1693–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; Alacid, F.; López-Plaza, D.; Muyor, J.M.; López-Miñarro, P.A. Kinematic Variables Evolution during a 200-m Maximum Test in Young Paddlers. J. Hum. Kinet. 2013, 38, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzka, M.; Zinner, C.; Kunz, P.; Holmberg, H.C.; Sperlich, B. Comparison of Physiological Parameters During On-Water and Ergometer Kayaking and Their Relationship to Performance in Sprint Kayak Competitions. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padulo, J.; Borrelli, M.; Antiglio, A.; Esposito, F. Gait Variability and Fatigability during a Simulated 10-km Running Race in Trained Runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; Manenti, G.; Esposito, F. The Impact of Training Load on Running Gait Variability: A Pilot Study. Acta Kinesiol. 2023, 17, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbán, T.; Caballero, C.; Barbado, D.; Moreno, F.J. Do Intentionality Constraints Shape the Relationship between Motor Variability and Performance? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, B.; Bortolan, L.; Schena, F. Poling Force Analysis in Diagonal Stride at Different Grades in Cross Country Skiers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, W.; Cardinale, M.; McNeal, J.; Murray, S.; Sole, C.; Reed, J.; Apostolopoulos, N.; Stone, M. Recommendations for Measurement and Management of an Elite Athlete. Sports 2019, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; Ayalon, M.; Barbieri, F.A.; Di Capua, R.; Doria, C.; Ardigò, L.P.; Dello Iacono, A. Effects of Gradient and Speed on Uphill Running Gait Variability. Sports Health 2023, 15, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.E.; Sainburg, R.L. Interlimb Differences in Coordination of Unsupported Reaching Movements. Neuroscience 2017, 350, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Lee, S. Ground Kayak Paddling Exercise Improves Postural Balance, Muscle Performance, and Cognitive Function in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 3909–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.C.; Aughey, R.J.; Ball, K.; Hopkins, W.G.; Siegel, R. Technical Determinants of On-Water Rowing Performance. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 589013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romagnoli, C.; Ditroilo, M.; Bonaiuto, V.; Annino, G.; Gatta, G. Paddle Propulsive Force and Power Balance: A New Approach to Performance Assessment in Flatwater Kayaking. Sports Biomech. 2022, 24, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The Coefficient of Determination R-Squared Is More Informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in Regression Analysis Evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglione, A.; Lazzer, S.; Colli, R.; Introini, E.; di Prampero, P.E. Energetics of Best Performances in Elite Kayakers and Canoeists. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messias, L.H.D.; Dos Reis, I.G.M.; Bielik, V.; Garbuio, A.L.P.; Gobatto, C.A.; Manchado-Gobatto, F.B. Association Between Mechanical, Physiological, and Technical Parameters with Canoe Slalom Performance: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 734806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Fazio, R.; Mastronardi, V.M.; De Vittorio, M.; Visconti, P. Wearable Sensors and Smart Devices to Monitor Rehabilitation Parameters and Sports Performance: An Overview. Sensors 2023, 23, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Acronym | Notes/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Acceleration (m·s−2) | ACC | Longitudinal acceleration by accelerometer (Anolog Devices ADXL330, Wilmington, NC, USA). |

| Time (s) | TIME | Total time required to complete the 500 m, measured using a digital stopwatch (Seiko® S141). |

| Speed (m·s−1) | V | Average speed calculated as distance divided by time; the standard distance was 500 m. |

| Frequency (stroke·min−1) | FREQ | Stroke frequency: 60, 80, and 100 strokes·min−1. |

| Weekly training (h) | HRWEEK | Total weekly training hours. |

| Transmission efficiency (%) | TE | Percentage efficiency indicator, representing how much of the athlete’s generated force or energy is effectively transferred to the paddle/kayak. Formula: TE(%) = Output/Input × 100. |

| Human mechanical work (kJ) | HExW | External mechanical work done by the athlete, excluding internal losses. Estimated as HExW = F × d, where F is force on the paddle, and d is distance covered. |

| Boat mechanical work (kJ) | BExW | External mechanical work done on the boat, computed from wave drag, friction drag, and pressure drag and the displacements were determined using a triaxial accelerometer. |

| Foot 2D Wcom (J·kg−1·m−1) | F2D | Estimates 2D mechanical work at the foot level. |

| Foot |vy| (m·s−1) | FAP | Instantaneous velocity (2D antero-posterior and medio-lateral) of the foot’s center of pressure (COP) over time. |

| Foot 2D Pcom (J) | F2P | Two-dimensional antero-posterior and medio-lateral COP position on foot over time. Firstly, used to calculate its instantaneous velocity (v [m/s]). Then v was put into the mechanical kinetic energy (J per stroke) (Ek) equation: Ek = m·v2, where m as subject’s mass. |

| Stroke frequency variability | SDA100FARPM | The standard deviation of the average cycle-to-cycle intervals over 100 cycles of accelerometry frequency. |

| Stroke frequency variability | SDA100FPRPM | The standard deviation of the average cycle-to-cycle intervals over 100 cycles of foot sensors frequency. |

| Stroke frequency variability | SDA100FSRPM | The standard deviation of the average cycle-to-cycle intervals over 100 cycles of seat sensors frequency. |

| Power variability | SDA100EP | The standard deviation of the average cycle-to-cycle intervals over 100 cycles of foot energy. |

| Power variability | SDA100ES | The standard deviation of the average cycle-to-cycle intervals over 100 cycles of seat energy. |

| Seat 2D Wcom (J·kg−1·m−1) | S2D | Two-dimensional mechanical work at the seat level. |

| Seat vy (m·s−1) | SAP | Instantaneous seat velocity from antero-posterior and medio-lateral COP data. |

| Seat 2D Pcom (J) | S2DP | Mechanical kinetic energy at the seat, using Ek = m v2, where m is the athlete’s mass. |

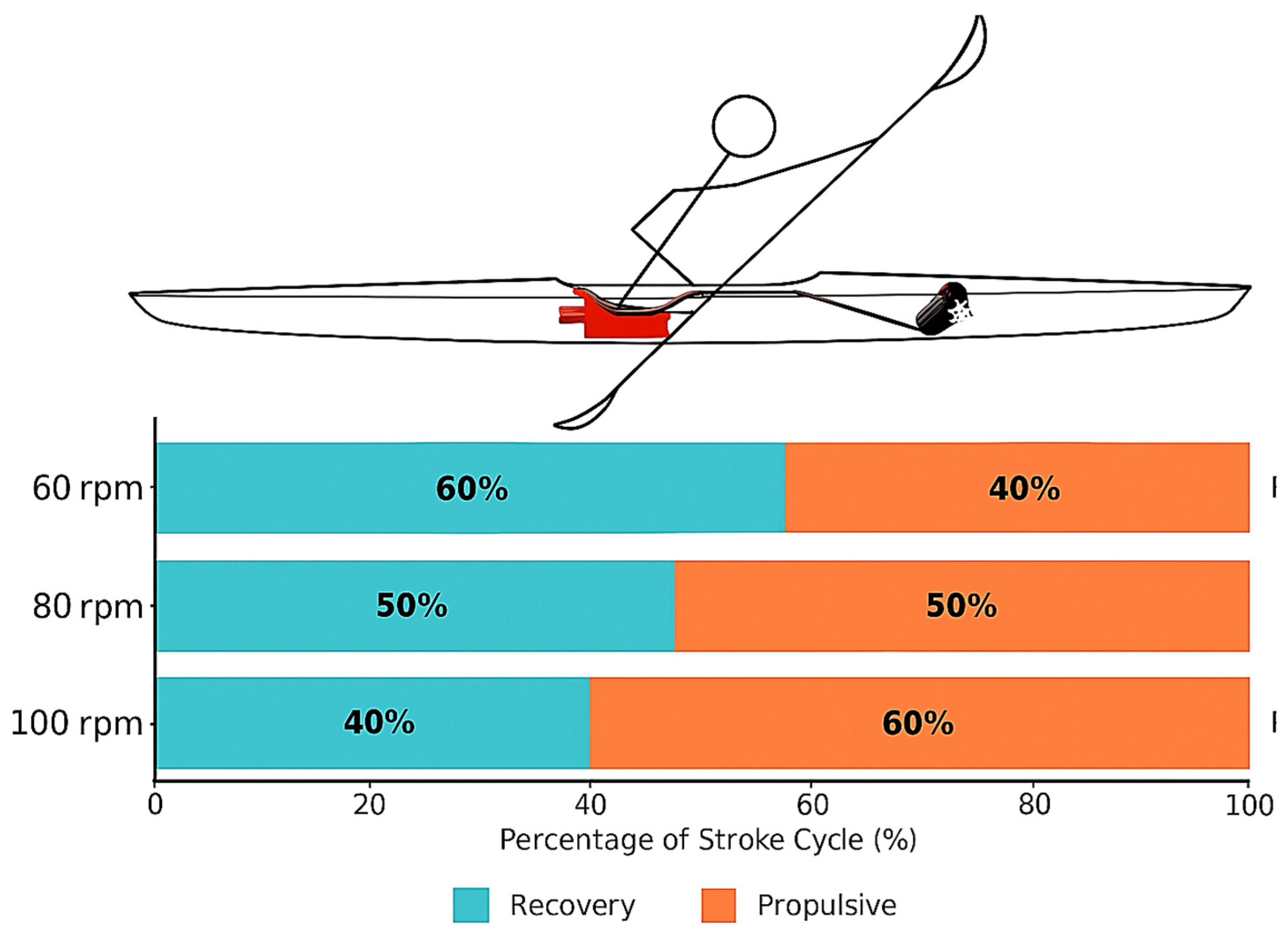

| Paddle Factor (% sec) | PF | Ratio of stroke cycle time spent in the propulsion phase, i.e., 100 (Equation (9)). |

| Phase Coordination Index (%) | PCI | Index measuring bilateral coordination of paddling using phase variability and accuracy [26]. |

| Bilateral Asymmetry (%) | BASY | Index based on Robinson’s method to quantify asymmetry between right and left limbs [27]. |

| Variables (Units) | Paddle Frequencies (Strokes·min−1) | ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 80 | 100 | F-Test (DF) | p-Value | |

| SDA100FARPM (strokes·min−1) | 1.50 ± 0.24 | 0.88 ± 0.23 | 1.03 ± 0.23 | 2.48 (2, 22.53) | 0.106 |

| SDA100ES (strokes·min−1) | 0.92 ± 0.34 ‡ | 1.03 ± 0.33 | 1.40 ± 0.33 | 3.87 (2, 22.05) | 0.036 |

| FAP (m·s−1) | 0.12 ± 0.01 †‡ | 0.15 ± 0.01 * | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 42.37 (2, 22.03) | <0.0001 |

| S2D (J·kg−1·m−1) | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 2.90 (2, 22.04) | 0.076 |

| SAP (m·s−1) | 0.11 ± 0.02 ‡ | 0.13 ± 0.02 * | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 16.03 (2, 22.03) | <0.0001 |

| S2DP (J) | 1.57 ± 0.78 ‡ | 2.12 ± 0.77 | 3.14 ± 0.76 | 4.30 (2, 22.10) | 0.0265 |

| HExW (kJ) | 46.1 ± 9.59 ‡ | 60.5 ± 9.40 | 71.1 ± 9.32 | 5.17 (2, 22.14) | 0.0144 |

| PCI (%) | 3.32 ± 1.80 ‡ | 2.34 ± 0.60 | 2.78 ± 0.91 | 2.13 (2, 22.00) | 0.143 |

| SDA100EP (strokes·min−1) | 1.50 ± 0.47 †‡ | 2.80 ± 0.46 | 3.22 ± 0.46 | 19.88 (2, 22.07) | <0.0001 |

| F2D (J·kg·m−1) | 0.32 ± 0.05 †‡ | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 35.56 (2, 22.02) | <0.0001 |

| F2P (J) | 2.21 ± 0.69 †‡ | 3.84 ± 0.68 * | 5.16 ± 0.68 | 34.82 (2, 22.05) | <0.0001 |

| PF (% sec) | 0.18 ± 0.01 †‡ | 0.19 ± 0.01 * | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 53.34 (2, 22.10) | <0.0001 |

| BExW (kJ) | 18.5 ± 0.49 †‡ | 21.6 ± 0.47 * | 24.6 ± 0.46 | 72.54 (2, 22.28) | <0.0001 |

| BASY (%) | 6.54 ± 0.79 | 4.71 ± 0.75 | 5.41 ± 0.73 | 1.58 (2, 22.91) | 0.226 |

| SDA100FSRPM (strokes·min−1) | 1.48 ± 0.26 | 1.03 ± 0.25 | 1.21 ± 0.24 | 0.79 (2, 23.16) | 0.465 |

| ACC (m·s−2) | 0.04 ± 0.004 | 0.03 ± 0.004 * | 0.04 ± 0.003 | 3.75 (2, 22.34) | 0.039 |

| Factor Loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | Component 4 | Commonalities | |

| SDA100FARPM | −0.40 | 0.24 | 0.61 | −0.05 | 0.59 |

| SDA100ES | 0.93 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.87 |

| FAP | −0.35 | 0.77 | −0.07 | −0.27 | 0.79 |

| S2D | 0.95 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.93 |

| SAP | 0.90 | −0.09 | −0.22 | 0.02 | 0.86 |

| S2DP | 0.96 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.92 |

| HExW | −0.37 | 0.57 | −0.26 | −0.26 | 0.59 |

| SDA100EP | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.87 |

| F2D | −0.03 | 0.83 | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0.87 |

| F2P | −0.16 | 0.89 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.88 |

| PF | 0.47 | 0.54 | −0.25 | 0.07 | 0.57 |

| BExW | 0.26 | 0.61 | −0.56 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| BASY | −0.36 | 0.07 | −0.50 | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| SDA100FSRPM | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.63 | −0.04 | 0.41 |

| ACC | 0.21 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.40 | 3.86 | 1.82 | 1.30 | |

| Percentage of variance | 29.33 | 25.73 | 12.13 | 8.67 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vando, S.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Melenco, I.; Dhahbi, W.; Russo, L.; Padulo, J. Stroke Frequency Effects on Coordination and Performance in Elite Kayakers. Biomechanics 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010002

Vando S, Peyré-Tartaruga LA, Melenco I, Dhahbi W, Russo L, Padulo J. Stroke Frequency Effects on Coordination and Performance in Elite Kayakers. Biomechanics. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleVando, Stefano, Leonardo Alexandre Peyré-Tartaruga, Ionel Melenco, Wissem Dhahbi, Luca Russo, and Johnny Padulo. 2026. "Stroke Frequency Effects on Coordination and Performance in Elite Kayakers" Biomechanics 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010002

APA StyleVando, S., Peyré-Tartaruga, L. A., Melenco, I., Dhahbi, W., Russo, L., & Padulo, J. (2026). Stroke Frequency Effects on Coordination and Performance in Elite Kayakers. Biomechanics, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010002